Abstract

Perfluoropentane (PFP), a highly hydrophobic, non-toxic, non-carcinogenic fluoroalkane, has generated much interest in biomedical applications, including occlusion therapy and controlled drug delivery. For most of these applications, the dispersion within aqueous media of a large quantity of PFP droplets of the proper size is critically important. Surprisingly, the interfacial tension of PFP against water in the presence of surfactants used to stabilize the emulsion has rarely, if ever, been measured. In this study, we report the interfacial tension of PFP in the presence of surfactants used in previous studies to produce emulsions for biomedical applications: polyethylene oxide-co-polylactic acid (PEO-PLA, and polyethylene oxide-co-poly-ε-caprolactone (PEO-PCL). Since both of these surfactants are uncharged diblock copolymers that rely on the mechanism of steric stabilization, we also investigate for comparison’s sake use of the small molecule cationic surfactant cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB), and the much larger protein surfactant bovine serum albumin (BSA). The results presented here complement previous reports of the PFP droplet size distribution, and will be useful for determining to what extent the interfacial tension value can be used to control the mean PFP droplet size.

Introduction

The unique physical, chemical and biological properties of perfluoropentane (PFP – see Figure 1) have generated much interest in its use in several biomedical applications such as propellants for pressurized metered dose inhalers (pMDIs) for direct delivery of drugs to lungs1, 2, ultrasound contrast enhancement3, and for transport of oxygen in vivo in artificial blood4–7. PFP also shows promise in the field of drug delivery and gene transfection8–11. Like almost all perfluorocarbons, PFP has a high capacity for absorbing oxygen. More importantly, the normal boiling point of PFP lies between room temperature and body temperature. This means that PFP can be injected in the form of liquid droplets dispersed in an aqueous medium, and then converted to bubbles using ultrasound. This conversion to bubbles can be used to release anti-cancer drugs such as doxorubicin at a site of interest11, or to occlude blood vessels that supply oxygen to tumors12.Obviously, the size of the blood vessels that can be occluded in such a way depends on the PFP droplet size in the injected emulsion. In addition, for passive targeting of hydrophobic drugs in PFP to tumors via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) mechanism, the PFP droplets must have the correct size range (10 – 100 nm) so that they only pass through the walls of blood vessels that supply tumors11. Thus for both of the applications, the ability to control the mean PFP droplet size is of paramount importance. The interfacial tension value, as determined by the surfactants employed, is most likely an important determinant.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of (a) PFP, (b) PEO-PLA, (c) PEO-ε-PCL and (d) CTAB

Figure 1(a) shows the chemical structure of PFP (C5F12, Molecular weight 288g/gmol), a member of the perfluorocarbon family. PFP is a liquid at room temperature but is a vapor at body temperature with a normal boiling point of 29.2 °C (Fluoromed, L. P. Product Information). At 25 °C its density of 1.63 g/ml is much greater than that of water and its kinematic viscosity is much lower than that of water, at 0.4 cSt.13–15 As a result of its non-polar, hydrophobic nature, the solubility of oxygen in PFP at 25 °C (mole fraction 5.8 × 10−3) is much higher than in water (mole fraction 2.3 × 10−5) (Fluoromed, L. P. Product Information). PFP has also proven to be a non-toxic, non-carcinogenic biocompatible material5, 7, 10.

Due to the hydrophobic nature of PFP, it has a very high interfacial tension against water and does not readily disperse or dissolve in hydrophilic fluids. Hence, lowering the interfacial tension of PFP with surfactants is important for improving its dispersion in aqueous media. For delivery of doxorubicin in PFP droplets to tumors, Rapoport et al.11 used the surfactants polyethylene oxide-co-polylactic acid (PEO-PLA, L-form) or polyethylene oxide-co-poly-ε-caprolactone (PEO-PCL), which are uncharged block copolymers. The hydrophobic block (PLA or PCL) is thought to adsorb on the PFP surface, and the hydrophilic PEO block is thought to form a “brush” that stabilizes the droplets against coalescence.

In contrast, cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) is a well known cationic surfactant with a relatively low molecular mass. The chemical structures of the surfactants are shown in Figure 1 (b–d). Above a certain concentration known as the critical micelle concentration (CMC) these surfactants form spherical core-shell type micelles13. Typical CMC values for CTAB and BCP surfactants of similar molecular weights, from literature, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Molecular weights of the surfactants used in this study and CMC values from literature for CTAB and for BCP surfactants of similar molecular weights.

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) is a negatively charged globular protein and the most abundant protein in mammalian serum (4 weight % in human serum). It possesses a prolate ellipsoid tertiary structure with dimensions 4×4×14nm. BSA has been shown to adsorb and denature at air-water interface and reach an equilibrium surface tension of ~53 dyn/cm38. Kripfgans et al studied PFP-BSA emulsion stability and droplet size distribution, for occlusion therapy and ultrasound contrast applications12. They found that the PFP droplets in BSA solutions were stable against spontaneous vaporization at physiological temperature (37 °C) and ultrasonic scanning up to certain pressure thresholds and that their mean diameter and number density could be controlled by altering the concentration of BSA.

Due to their high molecular weights, BCP surfactants such as PEO-PLA and PEO-PCL possess a significantly lower CMC than the smaller, non-polymeric surfactant CTAB14–21.

The biocompatibility and biodegradability of PEO-PLA and PEO-PCL have been exploited in several biomedical applications such as bio-resorbable sutures, orthopedic screws, coating materials, implants and drug delivery 14, 23–33. Micelles formed by PEO-PLA and PEO-PCL are of particular interest because they can be used to sequester anti-cancer drugs, which are then delivered to tumors using PFP droplets11. CTAB, a cationic surfactant, has been used in several cosmetic products, topical antiseptic creams and recently for the isolation of DNA from solutions containing other polysaccharides34, 35.

No critical micelle concentration can be defined for BSA since it is not an amphiphilic surfactant. However, an apparent critical micelle concentration of ~0.076 µM is reported in literature22. BSA has been studied as a potential emulsifier for PFP for occlusion therapy and ultrasound contrast enhancement12.

The interfacial behavior of hydrogenated or oxygenated fluoroalkanes in aqueous solutions containing low molecular weight surfactants, Pluronics1, 2, and phospholipids9, 10, 36, 37 has been documented. However, the interfacial tension of perfluropentane in aqueous solutions containing surfactants of any type has not, to our knowledge, been reported in literature. Thus the goal of this work is to compare the interfacial tension of the PFP/water interface in the presence of the surfactants used in recent studies11–12 to stabilize PFP emulsions for biomedical or pharmaceutical use.

Experimental section

Materials

Research grade PFP was purchased from Fluoromed L.P. and stored in the refrigerator at 0°C in a sealed container. PEO114-b-PLA65 diblock copolymer (Table 1) was purchased from Polymer Source Inc., Canada in a crystalline form. Because PEO-PLA crystals do not readily dissolve in water13, the aqueous solution of this BCP was prepared following a multi-step process.11 First, 0.125 grams of the polymer were dissolved in 5 ml of THF with 20 ml of distilled water. Next, the organic solvent was removed by running the solution through a membrane tube with a molecular weight cut-off of 3500 Da (Spectra/Por, Spectrum Labs Inc., GA) followed by dialysis with water and 0.15M Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS). Distilled water was used to replace the volume of the organic solvent removed during the previous step to obtain the final 0.5% by weight PEO-PLA solution. The solution was allowed to homogenize by gentle agitation and stored in the refrigerator when not in use. The solutions were diluted with 0.15M PBS to get desired concentrations. PEO45-b-PCL23 diblock copolymer (Table 1) was also obtained from Polymer Source Inc., Canada and micellar solutions were prepared in a similar fashion.

Analytical grade CTAB was purchased from Sigma. A 1mM solution of CTAB in 0.15M PBS was prepared and mixed by gentle agitation for 1–2 minutes and stored at room temperature.

Purified BSA (RIA and ELISA grade) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, USA). Solutions were prepared in 0.15M PBS, stored at ~0 °C and used within 24 hours of preparation.

Surface and Interfacial Tension Measurements

Gas tight glass syringes (250µl), flat-tip stainless steel needles (14 gauge) and a two-way stainless steel valve were purchased from the Hamilton Company.

The syringe, needle and valve were thoroughly cleaned before use and dried. The valve was used to control the flow of PFP from the syringe to the needle and control the size of the liquid drops. A glass environmental cell was cleaned thoroughly with distilled water and allowed to dry completely. For interfacial tension measurements, this cell was filled with surfactant solution.

The needle was then placed into the airtight glass cell as shown in Figure 2. For interfacial tension measurements, the needle tip was submerged in surfactant solution and the temperature in the cell was constantly monitored using a wire thermocouple in direct contact with the solution.

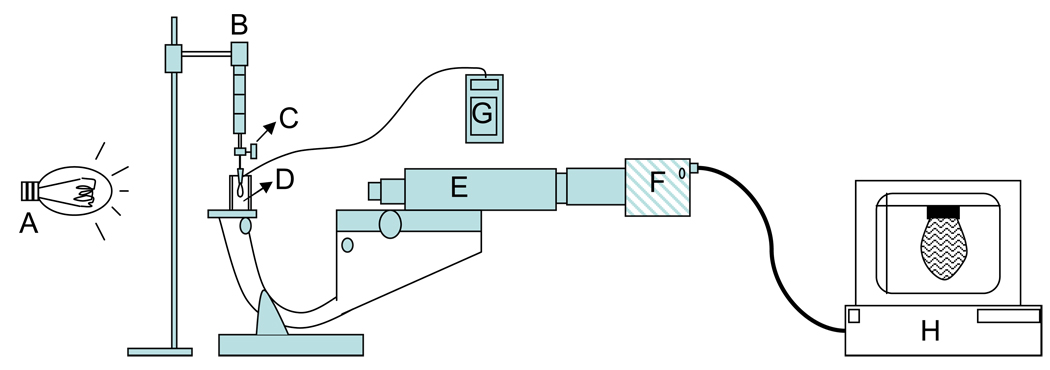

Figure 2.

Experimental apparatus for surface/interfacial tension measurements. A: Light source, B: Syringe, C: Two-way valve, D: Air tight glass cell, E: Microscope, F: CCD Camera, G: Temperature Monitor and H: Computer

All measurements were performed at room temperature (24 °C ± 1 °C).

PFP drops were injected into the surfactant solution and images were captured using the CCD camera (Fig. 3.). The first image was captured 5–10 seconds after the formation of the drop. The images were then converted into pixel coordinates, then into coordinates in centimeters using Image 1.37 software.

Figure 3.

Image of a PFP drop in PEG-PLA surfactant solution captured by the CCD camera

The images were next analyzed using an Axisymmetric Drop Shape Analysis-Profile (ADSAP) program38 that fits the drop coordinates to the Young-Laplace equation (Y-L equation) of capillarity.

The Y-L equation as described here is specifically for pendant drops and is derived by a force-balance over the suspended drop. This equation relates the pressure difference Δp across an interface between two fluids to the curvature of the interface, caused by the phenomenon of surface tension.

| (1) |

where γ is the surface/interfacial tension and R1, R2 are the principle radii of curvature. The ADSAP program uses numerical integration to develop theoretical drop profiles to match the experimental drop profiles (Fig. 4.). Surface/Interfacial tension, drop volume, drop surface area and the radius of curvature of the drop were obtained by running the ADSAP program.

Figure 4.

Comparison of theoretical and experimental interface profile of a drop obtained through ADSAP

Results and Discussion

Bond Numbers

The Bond number (Bo) is a dimensionless group which represents the ratio between gravitational force and surface/interfacial tension forces acting on a pendant drop39, 40 and is equal to:

| (2) |

where Δρ is the density difference at the surface or interface, g is the acceleration due to gravity, Ro is the radius of curvature of the drop at the apex and γ is the surface or interfacial tension.

Spherical drops are obtained when this ratio is small.

In the presence of surfactants the drop assumes a pendant like ellipsoidal shape rather than a spherical shape due to adsorption of molecules at the interface resulting in a decrease in interfacial tension and an increase in the Bond number.

For an accurate pendant drop experiment it is necessary that the drops have a pendant like or ellipsoidal shape rather than a spherical shape. For spherical drops, the fit between the experimental and theoretical drop profile becomes independent of the surface/interfacial tension values38, 39. This occurs when Bo << 0.1.

Bond numbers were calculated for the pendant drops for all the systems studied. The average values are listed in Tables 2 and 3. For accurate results the Bond number should lie between 0.1 and 0.640. For all our systems, the Bond numbers for the pendant drops were within this range.

Table 2.

Literature and experimental values of equilibrium surface tensions of surfactants at 25°C measured in this study.

| Material | Concentration (mM) |

Solvent | Equilibrium Surface Tension (dyn/cm) |

Literature Value (in distilled water) |

Bond Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFP (99% purity) | -- | -- | 9.41 | 9.42a | 0.42 |

| CTAB | 1 1 0.4 |

Distilled Water 0.15M PBS 0.15M PBS |

29 27 27 |

35–38b |

0.46 0.41 |

| PEO-PLA | 0.15 0.26 |

0.15M PBS | 43 47 |

45–46c | 0.41 0.41 |

| PEO-PCL | 0.54 | 0.15M PBS | 47 | 49–52d | 0.39 |

| BSA | 0.015 | 0.15 M PBS | 43 | 53e | 0.40 |

Table 3.

Interfacial tensions of PFP against water or 0.15M PBS containing various surfactants at the concentrations given in the table.

| Interface | Surfactant | Surfactant Concentration (mM) |

Interfacial Tension (dyn/cm) (±1–4 dyn/cm) |

Bond Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFP-PBS | -- | -- | 49 | 0.14 |

| PFP-Water | -- | -- | 54 56a |

0.15 |

| PFP-PBS | PEO-PLA | 0.0103 0.052 0.103 0.26 |

38 31 29 27 |

0.17 0.15 0.17 0.18 |

| PFP-PBS | PEO-PCL | 0.54 | 30 | 0.17 |

| PFP-PBS | CTAB | 0.05 0.1 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 |

17.7 15.2 12.6 8.5 10 10.7 10 |

0.42 0.44 0.46 0.52 0.48 0.46 0.58 |

| PFP-PBS | BSA | 0.015 0.045 0.075 0.152 0.227 |

31.1 33.4 28.0 31.9 30.8 |

0.58 0.58 0.52 0.56 0.56 |

Reference 53

The highest Bond numbers were obtained for systems involving CTAB surfactants, which were also the systems with the lowest surface/interfacial tension values.

Surface Tension of PFP at Liquid/Air Interface

The surface tensions of PFP, distilled water, 0.15M PBS, and various surfactant solutions were all measured against saturated air at room temperature. These measurements, which are not novel, are compared to values reported by previous authors as a check on our materials and experimental techniques. The measurements were repeatable with a low standard deviation (Table 2). Table 2 lists the measured equilibrium surface tension of the surfactant solutions (in PBS buffer) as well as literature values for solutions containing the same or similar (for the BCP) surfactants at their critical micelle concentrations in distilled water. Our measured values are in reasonable agreement with the literature values, with the possible exception of the BSA solution. As reported previously,39 the surface activity of proteins often varies with the supplier and also changes after repeated freeze-thaw cycles. The surface tension of distilled water (68 dyn/cm) was also found to be a little lower than the literature value of 72 dyn/cm, which we attribute to accumulation of contaminants in water over the course of the experiment or fluctuations in room temperature. The lowest surface tension value is obtained using the surfactant CTAB, which is unsurprising because it has the highest CMC value. As mentioned in Table 1, the literature values for the CMCs of PEO-PLA and PEO-PCL BCPs in aqueous solutions are very low14, 15, 24, 26, 29, 41–46. CTAB, on the other hand, has a CMC value which is at least two orders of magnitude larger. Above the CMC, the surface tension becomes approximately independent of concentration, presumably because the concentration of unimers stays close to the CMC value, and unimers are much more surface-active than micelles. Hence, even though our surfactant solution bulk concentrations were greater than the CMC value, the equilibrium surface tension values are nearly the same as the values reported at the CMC (Table 2). Similarly, for BSA, an apparent CMC of ~0.076µM has been reported in the literature22 with a constant equilibrium surface tension of 53–55mN/m at higher concentrations38, 47.

Interfacial Tension of PFP against aqueous solutions

In the absence of any surfactants, the interfacial tension of PFP against pure distilled water was measured to be 54 dyn/cm, in excellent agreement with the literature value of 56 dyn/cm 53. Against 0.15M PBS, the measured value was 49 dyn/cm. These very high values reflect the hydrophobicity of PFP, and hence surfactants are needed to disperse PFP in water.

In the presence of the block copolymer surfactants, the interfacial tension of PFP against water was measured in our lab to be about 27 dyn/cm for PEO-PLA, and about 30 dyn/cm for PEO-PCL (Table 3). All concentrations studied were above the CMC of the block copolymers, which probably explains why no concentration dependence is observed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Interfacial tension between 0.15M PBS and PFP as a function of bulk surfactant concentrations at 24°C. (●)PEO-PLA, (▲) BSA and (■) CTAB. The vertical arrow gives the location of the literature CMC value for CTAB; the CMC values for BSA and PEO-PLA are both below 0.01 mM. Note: Some error bars are not visible as they are smaller than or equal to the size of the symbols used due to very small standard deviations (< 1 dyn/cm)

In the presence of BSA, the interfacial tension of PFP against water was measured as about 31 dyn/cm (Table 3) at all concentrations studied. In the presence of CTAB, a cationic surfactant, the interfacial tension of PFP against water reaches its lowest value, about 11 dyn/cm, at a concentrations about one-half of the reported CMC value (Figure 5). As with the surface tension, the differing IFT behavior between CTAB on one hand and BSA, PEO-PLA, and PEO-PCL on the other hand can be explained by the much larger CMC value of CTAB. In all the surfactant solutions, the unimer concentration should be close to the CMC value, and this is at least two orders of magnitude larger for CTAB than for the macromolecular surfactants. Thus more surface-active species are available for adsorption on the PFP surface when in contact with the CTAB solution. Given the very low CMC values of PEO-PLA and PEO-PCL, they are surprisingly effective in lowering the tension of the PFP/water interface. This suggests that the molecular size of the adsorbed species is also an important consideration. Globular BSA has dimensions of 4 nm by 4 nm by 14 nm54, spherical random coils of PEO-PLA have a hydrodynamic radius of about 35nm13, whereas the fully-extended CTAB tail has a length of 2.2nm and width of 0.3–0.5nm55.

Significance to PFP Pharmaceutical Emulsion Preparation

Aqueous emulsions containing perfluorocarbons such as PFP11, 12, perfluorobutane 56 or decafluoropentane 57 suitable for biomedical applications such as occlusion and drug delivery have been prepared using the surfactants PEO-PCL, PEO-PLA, BSA, and sodium cholate11, 12, 57 without knowledge of the interfacial tension value. The results presented here show that all three of the macromolecular surfactants give similar values for the IFT value at high surfactant concentrations, approximately 30 dyne/cm. Perhaps this is the IFT value which produces the optimum drop size distribution (10–100 nm for EPR11), a proposition that we are checking by preparing PFP emulsions using CTAB as a surfactant. The results presented here also can be used to infer the minimum amount of surfactant that can be used to stabilize PFP emulsions. For example, Kripfagans et al has reported using BSA concentrations of 0.015–0.24 mM (~1–16 mg/ml)12. The results in Figure 5 suggest that this is excessive, because the IFT reaches its asymptotic value at a BSA concentration below 0.015 mM.

Conclusions

The very high interfacial tension value of PFP against water or PBS can be substantially lowered by all the surfactants studied: the BCP surfactants PEO-PLA and PEO-PCL, the low molecular weight cationic surfactant CTAB, and the anionic protein surfactant BSA. All of the macromolecular surfactants have been used previously to prepare stable PFP emulsions, whereas molecular-size CTAB has not. All of the macromolecular surfactants give a similar value for the PFP/water tension (≈30 dyne/cm) which is independent of concentration, at least above very low reported CMC values. CTAB, which has a CMC value that is orders of magnitude larger, gives a limiting value for the tension of the PFP/water interface that is lower (10 dyne/cm). Given its low CMC value, PEO-PLA is surprisingly effective in lowering the tension of the PFP/water interface, probably because of its colloidal size. Furthermore, adsorption of the BCP likely gives rise to a PEO “brush” that stabilizes PFP droplets against coalescence or protein adsorption. The reduction in the surface tension of PBS buffer (against air) by PEO-PLA is also large. This may be relevant to biomedical applications in which the PFP liquid droplet is converted to a vapor within the body using ultrasound11, and the PFP vapor contains a significant mole fraction of oxygen due to dissolution of oxygen from the surrounding aqueous solution into the PFP bubble58.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Natalya Rapoport for useful discussions. Acknowledgement is made by M. K., G. L. and J. J. M to the donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (grant 45968-AC9) and to the National Institutes of Health (grant EB004947). P.M. and M.S. acknowledge support of the American Heart Association Established Investigator Award.

References

- 1.Rogueda PGA. HPFP, a Model Propellant for pMDIs. Drug Development & Industrial Pharmacy. 2003;29(1):39. doi: 10.1081/ddc-120016682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selvam P, Peguin RPS, Chokshi U, da Rocha SRP. Surfactant Design for the 1,1,1,2-Tetrafluoroethane Water Interface: ab initio Calculations and in situ High-Pressure Tensiometry. Langmuir. 2006;22(21):8675–8683. doi: 10.1021/la061015z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Miyoshi H, Nakamura M. Encapsulated ultrasound microbubbles: Therapeutic application in drug/gene delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;114(1):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowe KC. Fluorinated blood substitutes and oxygen carriers. Journal of Fluorine Chemistry. 2001;109(1):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris GW, Anderson RM, Defilippi RP, Nosé Y, Weber DC, Malchesky PS. The physiological effects of fluorocarbon liquids in blood oxygenation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1970;4(3):313–339. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter TR, Xie F, Kricsfeld A, Kilzer K. Noninvasive identification of acute myocardial ischemia and reperfusion with contrast ultrasound using intravenous perfluoropropane-exposed sonicated dextrose albumin. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1995;26(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00132-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross U, Papke G, Rudiger S. Fluorocarbons as blood substitutes: critical solution temperatures of some perflurocarbons and their mixtures. Journal of Fluorine Chemistry. 1993;61(1–2):11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soman NR, Lanza GM, Heuser JM, Schlesinger PH, Wickline SA. Synthesis and Characterization of Stable Fluorocarbon Nanostructures as Drug Delivery Vehicles for Cytolytic Peptides. Nano Letters. 2008;8(4):1131–1136. doi: 10.1021/nl073290r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krafft MP, Riess JG. Perfluorocarbons: Life sciences and biomedical uses. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2007;45(7):1185–1198. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerber F, Krafft MP, Vandamme T, Goldmann M, Fontaine P. Potential Use of Fluorocarbons in Lung Surfactant Therapy. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology. 2007;35:211–220. doi: 10.1080/10731190601188307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapoport N, Gao Z, Kennedy A. Multifunctional Nanoparticles for Combining Ultrasonic Tumor Imaging and Targeted Chemotherapy. Journal of The National Cancer Institute. 2007;99(14):1095–1106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kripfgans OD, Fowlkes JB, Miller DL, Eldevik OP, Carson PL. Acoustic droplet vaporization for therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2000;26(7):1177–1189. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(00)00262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley T, Stolnik S, Heald CR, Xiong CD, Garnett MC, Illum L, Davis SS, Purkiss SC, Barlow RJ, Gellert PR. Physicochemical Evaluation of Nanoparticles Assembled from Poly(lactic acid)-Poly(ethylene glycol) (PLA-PEG) Block Copolymers as Drug Delivery Vehicles. Langmuir. 2001;17(11):3168. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierri E, Avgoustakis K. Poly(lactide)-poly(ethylene glycol) micelles as a carrier for griseofulvin. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2005;75A(3):639–647. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leyh B, Vangeyte P, Heinrich M, Auvray L, De Clercq C, Jérôme R. Self-assembling of poly(ε-caprolactone)-b-poly(ethylene oxide) diblock copolymers in aqueous solution and at the silica-water interface. Physica B: Condensed Matter. 2004;350(1–3) Supplement 1:E901–E904. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu C, Guo S, Liu L, Zhang Y, Li Z, Gu J. Aggregation behavior of MPEG-PCL diblock copolymers in aqueous solutions and morphologies of the aggregates. Journal of polymer science. Part B. Polymer physics. 2006;44(23):3406–3417. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergeron V. Disjoining Pressures and Film Stability of Alkyltrimethylammonium Bromide Foam Films. Langmuir. 1997;13(13):3474–3482. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sepulveda L, Cortes J. Ionization degrees and critical micelle concentrations of hexadecyltrimethylammonium and tetradecyltrimethylammonium micelles with different counterions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 1985;89(24):5322–5324. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paredes S, Tribout M, Sepulveda L. Enthalpies of micellization of the quaternary tetradecyl- and -cetyl ammonium salts. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1984;88(9):1871–1875. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui X, Mao S, Liu M, Yuan H, Du Y. Mechanism of Surfactant Micelle Formation. Langmuir. 2008;24(19):10771–10775. doi: 10.1021/la801705y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai Y, Xu G-Y, Xin X, Sun H-Y, Zhang H-X, Hao A-Y, Yang X-D, Yao L. Interaction between cetyltrimethylammonium bromide and cyclodextrin: surface tension and interfacial dilational viscoelasticity studies. Colloid and Polymer Science. 2008;286:1475–1484. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Busscher HJ, van der Vegt W, Noordmans J, Schakenraad JM, van der Mei HC. Colloids Surf. 1991;58 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen C, Han J, Yu Y, Maysinger D, Eisenberg A. Polycaprolactone-b-poly(ethylene oxide) copolymer micelles as a delivery vehicle for dihydrotestosterone. Journal of Controlled Release. 2000;63(3):275–286. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagan SA, Coombes AGA, Garnett MC, Dunn SE, Davies MC, Illum L, Davis SS, Harding SE, Purkiss S, Gellert PR. Polylactide-Poly(ethylene glycol) Copolymers as Drug Delivery Systems. 1. Characterization of Water Dispersible Micelle-Forming Systems. Langmuir. 1996;12(9):2153–2161. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu S-H, Tang C-M, Lin C-C. Biocompatibility of poly(ε-caprolactone)/poly(ethylene glycol) diblock copolymers with nanophase separation. Biomaterials. 2004;25(25):5593–5601. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jongpaiboonkit L, Zhou Z, Ni X, Wang Y-Z, Li J. Self-association and micelle formation of biodegradable poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(L-lactic acid) amphiphilic di-block co-polymers. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2006;17:747–763. doi: 10.1163/156856206777656553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khor HL, Ng KW, Schantz JT, Phan T-T, Lim TC, Teoh SH, Hutmacher DW. Poly(ε-caprolactone) films as a potential substrate for tissue engineering an epidermal equivalent. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2002;20(1–2):71–75. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Li C, Li X, Yuan Z, An Y, He B. Biodegradable polylactide/poly(ethylene glycol)/polylactide triblock copolymer micelles as anticancer drug carriers. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2001;80(11):1976–1982. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Qi XR, Maitani Y, Nagai T. PEG-PLA diblock copolymer micelle-like nanoparticles as all-trans-retinoic acid carrier: in-vitro and in-vivo characterizations. Nanotechnology. 2009;20(5):055106. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/5/055106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miura H, Onishi H, Sasatsu M, Machida Y. Antitumor characteristics of methoxypolyethylene glycol-poly(dl-lactic acid) nanoparticles containing camptothecin. Journal of Controlled Release. 2004;97(1):101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrano MC, Pagani R, Vallet-Regí M, Peña J, Rámila A, Izquierdo I, Portolés MT. In vitro biocompatibility assessment of poly(ε-caprolactone) films using L929 mouse fibroblasts. Biomaterials. 2004;25(25):5603–5611. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Burt HM, Hoff DV, Dexter D, Mangold G, Degen D, Oktaba AM, Hunter WL. An investigation of the antitumour activity and biodistribution of polymeric micellar paclitaxel. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 1997;40(1):81–86. doi: 10.1007/s002800050630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong Z, Sun XS. Properties of soy protein isolate/polycaprolactone blends compatibilized by methylene diphenyl diisocyanate. Polymer. 2001;42(16):6961–6969. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simões M, Pereira M, Machado I, Simões L, Vieira M. Comparative antibacterial potential of selected aldehyde-based biocides and surfactants against planktonic Pseudomonas fluorescens. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2006;33(9):741–749. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porebski S, Bailey L, Baum B. Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 1997;15(1):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertilla SM, Thomas J-L, Marie P, Krafft MP. Cosurfactant Effect of a Semifluorinated Alkane at a Fluorocarbon/Water Interface: Impact on the Stabilization of Fluorocarbon-in-Water Emulsions. Langmuir. 2004;20(10):3920–3924. doi: 10.1021/la036381m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgess DJ, Yoon JK. Influence of interfacial properties on perfluorocarbon/aqueous emulsion stability. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 1995;4(5):297–308. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tripp BC, Magda JJ, Andrade JD. Adsorption of Globular Proteins at the Air/Water Interface as Measured via Dynamic Surface Tension: Concentration Dependence, Mass-Transfer Considerations, and Adsorption Kinetics. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 1995;173(1):16–27. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tripp BC. Ph.D. Dissertation. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah, United States -- Utah, University of Utah; 1993. Dynamic surface tension of model protein solutions measured via pendant drop tensiometry. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim J-W, Kim H, Lee M, Magda JJ. Interfacial Tension of a Nematic Liquid Crystal/Water Interface with Homeotropic Surface Alignment. Langmuir. 2004;20(19):8110–8113. doi: 10.1021/la049843k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanodekaew S, Pannu R, Heatley F, Attwood D, Booth C. Association and surface properties of diblock copolymers of ethylene oxide and DL-lactide in aqueous solution. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 1997;198(4):927–944. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang L, Zhao Z, Wei J, El Ghzaoui A, Li S. Micelles formed by self-assembling of polylactide/poly(ethylene glycol) block copolymers in aqueous solutions. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2007;314(2):470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2007.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang W, Wang Y-D, Gan Q, Zhang J-Z, Zhao X-w, Fei W-Y, Bei J-Z, Wang S-G. Preparation and Characterization of Copolymer Micelles Formed by Poly(ethylene glycol)-Polylactide Block Copolymers as Novel Drug Carriers. Chinese Journal of Process Engineering. 2006;6(2):289–295. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai Z, Piao L, Zhang X, Deng M, Chen X, Jing X. Probing the micellization of diblock and triblock copolymers of poly(l-lactide) and poly(ethylene glycol) in aqueous and NaCl salt solutions. Colloid & Polymer Science. 2004;282(4):343–350. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vangeyte P, Leyh B, Auvray L, Grandjean J, Misselyn-Bauduin AM, Jerome R. Mixed Self-Assembly of Poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) Copolymers and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate in Aqueous Solution. Langmuir. 2004;20(21):9019–9028. doi: 10.1021/la048848e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vangeyte P, Leyh B, Heinrich M, Grandjean J, Bourgaux C, Jerome R. Self-Assembly of Poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) Copolymers in Aqueous Solution. Langmuir. 2004;20(20):8442–8451. doi: 10.1021/la049695y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClellan SJ, Franses EI. Effect of concentration and denaturation on adsorption and surface tension of bovine serum albumin. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2003;28:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freire MG, Carvalho PJ, Queimada AJ, Marrucho IM, Coutinho JAP. Surface Tension of Liquid Fluorocompounds. Journal of Chemical and Engineering Data. 2006;51(5):1820–1824. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rohrback GH, Cady GH. Surface tensions and refractive indices of the perfluoropentanes. JACS. 1949;71 [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLure IA, Soares VAM, Edmonds B. Surface tension of perfluoropropane, perfluoro-n-butane, perfluoro-n-hexane, perfluoro-octane, perfluorotributylamine and n-pentane. Application of the principle of corresponding states to the surface tension of perfluoroalkanes. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions 1: Physical Chemistry in Condensed Phases. 1982;78:2251–2257. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drummond CJ, Georgaklis G, Chan DYC. Fluorocarbons: Surface Free Energies and van der Waals Interaction. Langmuir. 1996;12(11):2617–2621. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gref R, Babak V, Bouillot P, Lukina I, Bodorev M, Dellacherie E. Interfacial and emulsion stabilising properties of amphiphilic water-soluble poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(lactic acid) copolymers for the fabrication of biocompatible nanoparticles. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 1998;143(2-3):413–420. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clasohm LY, Vakarelski IvanU, Dagastine RaymondR, Chan DerekYC, Stevens GeoffreyW, Grieser Franz. Anomalous pH Dependent Stability Behavior of Surfactant-Free Nonpolar Oil Drops in Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions. Langmuir. 2007;23(18):9335–9340. doi: 10.1021/la701568r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peters T. All about Albumin; Biochemistry, Genetics, and Medical Applications. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palazzo G, Lopez F, Giustini M, Colafemmina G, Ceglie A. Role of the Cosurfactant in the CTAB/Water/n-Pentanol/n-Hexane Water-in-Oil Microemulsion. 1. Pentanol Effect on the Microstructureâ€. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2003;107(8):1924–1931. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feshitan JA, Chen CC, Kwan JJ, Borden MA. Microbubble size isolation by differential centrifugation. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2009;329(2):316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang J, Xu J, Xu R. Heat-sensitive microbubbles for intraoperative assessment of cancer ablation margins. Biomaterials. 2010;31(6):1278–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wustneck N, Wustneck R, Pison U, Mohwald H. On the Dissolution of Vapors and Gases. Langmuir. 2006;23(4):1815–1823. doi: 10.1021/la0622931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]