Abstract

Breast cancer risk is increasing in most Asian female populations, but little is known about the long‐term mortality trend of the disease among these populations. We extracted data for Hong Kong (1979–2005), Japan (1963–2006), Korea (1985–2006), and Singapore (1963–2006) from the World Health Organization (WHO) mortality database and for Taiwan (1964–2007) from the Taiwan cancer registry. The annual age‐standardized, truncated (to ≥20 years) breast cancer death rates for 11 age groups were estimated and joinpoint regression was applied to detect significant changes in breast cancer mortality. We also compared age‐specific mortality rates for three calendar periods (1975–1984, 1985–1994, and 1995–2006). After 1990, breast cancer mortality tended to decrease slightly in Hong Kong and Singapore except for women aged 70+. In Taiwan and Japan, in contrast, breast cancer death rates increased throughout the entire study period. Before the 1990s, breast cancer death rates were almost the same in Taiwan and Japan; thereafter, up to 1996, they rose more steeply in Taiwan and then they began rising more rapidly in Japan than in Taiwan after 1996. The most rapid increases in breast cancer mortality, and for all age groups, were in Korea. Breast cancer mortality trends are expected to maintain the secular trend for the next decade mainly as the prevalence of risk factors changes and population ages in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Early detection and treatment improvement will continue to reduce the mortality rates in Hong Kong and Singapore as observed in Western countries.

(Cancer Sci 2010; 101: 1141–1246)

In Asian countries, the mortality rates from breast cancer are relatively lower than in Western, industrialized countries( 1 ) and have been on the increase until recently in China,( 2 , 3 ) Japan,( 4 ) Korea,( 5 , 6 ) and Taiwan.( 7 )

In contrast, breast cancer mortality has been declining in Western countries for decades.( 8 , 9 ) The decline has been explained in part by the cohort effect in women born after 1920 (a group that had more children and began childbearing at a lower age) and in part to improved management and treatment of women with the disease.( 9 )

In the 1980s, after it was shown in Sweden that mammography screening could lead to reduced breast cancer mortality,( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) other European countries started to establish screening programs.( 14 )

Because of the low breast cancer incidence rates in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, population‐based screening programs were not recommended in those populations until the early 1990s.( 15 , 16 , 17 ) Taiwan started mammography screening for high‐risk groups in 1995,( 18 ) and Japan,( 19 ) Korea,( 20 ) and Singapore( 16 , 21 ) started organized mammography screening programs in the early 2000s. In Hong Kong, screening is done by voluntary (‘opportunistic’) mammography.( 22 )

In this paper, we review the most available data on breast cancer mortality in Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, and we attempt to describe and compare their secular changing patterns.

Materials and Methods

We extracted annual breast cancer mortality data for Hong Kong (1979–2005), Japan (1963–2006), Korea (1985–2006), and Singapore (1963–2006) from the World Health Organization (WHO) mortality database and also used the WHO population data. We obtained mortality data for Taiwan (1964–2007) from the Taiwan Cancer Registry.

To detect significant changes in breast cancer mortality, we applied joinpoint regression using Joinpoint software version 3.3 (Surveillance Research Program, US National Cancer Institute) based on the Poisson assumption.( 23 ) We used the default settings and allowed a maximum of three joinpoints. To determine the change in breast cancer mortality by age group within a time period, we compared the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC). We also compared age‐specific mortality rates for three calendar periods (1975–1984, 1985–1994, and 1995–2006).

Results

Breast cancer mortality rates of the five study populations grew closer together over the past three decades in spite of the fact that the female populations in 2005 were about 2 to 7 times as large as they were in 1970 (Table 1). Breast cancer mortality in Singapore was the highest of the five, with relatively large yearly variations attributable to the relatively small female population. The mortality rate did not change significantly during 1963–2006 but increased slightly before 1990 (to 1.13% of the EAPC) and decreased slightly after 1990 (to −1.5% of the EAPC) (95% confidence interval [CI], −2.4 to −0.6). In Hong Kong, there was an overall decreasing tendency for breast cancer mortality during 1979–2005, with a −0.37% EAPC and a more rapid decline since 1991 (EAPC, −0.99%; 95% CI, −1.6 to −0.4). In Taiwan, Japan, and Korea, in contrast, breast cancer death rates increased throughout the entire study period.

Table 1.

Female breast cancer deaths, women aged ≥20 years and age‐adjusted breast cancer mortality rates in different calendar years by population

| Country/Region | Period | No. of breast cancer deaths | Population (≥20 years) in 1000s | Age‐adjusted breast cancer death rate (≥20 years) per 100 000 women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 2005 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2005 | |||

| Hong Kong | 1979–2005 | 8595 | 579 | 3063 | N/A | 13.3 | 14.4 | 13.1 |

| Japan | 1963–2006 | 239 477 | 23 748 | 57 780 | 7.27 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 14.3 |

| Korea | 1985–2006 | 20 789 | 4543 | 18 563 | N/A | N/A | 4.7 | 8.2 |

| Singapore | 1963–2006 | 6902 | 240 | 1641 | 15.8 | 23.1 | 23.4 | 16.6 |

| Taiwan | 1964–2007 | 25 549 | 3202 | 8405 | 7.34 | 8.7 | 11.5 | 16.4 |

N/A, data not available.

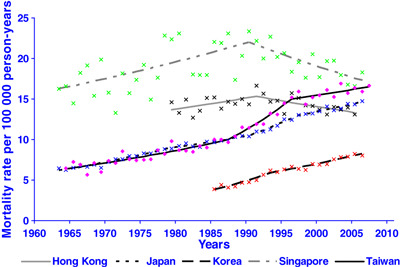

Before the 1990s, breast cancer death rates were almost the same in Taiwan and Japan; thereafter, up to 1996, they rose more steeply in Taiwan (EAPC, 4.63; 95% CI, 3.30–6.10) and then they began rising more rapidly in Japan (EAPC, 1.34; 95% CI, 0.9–10.8) than in Taiwan (EAPC, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.2–1.4) after 1996. The most significant increases were in Korea (EAPC, 3.41%; 95% CI, 3.17–3.65), which had the lowest mortality rate among the study populations (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Breast cancer mortality rate trend (truncated age‐standardized mortality rates) obtained by joinpoint regression in five female Asian populations, 1963–2007. The standard population is the age‐truncated population (≥20 years) of world standard population.

Table 2.

Estimated annual percent change (EAPC) of breast cancer death rates and 95% confidence intervals (CI)

| Country/Region | EAPC | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | |||

| 1979–1991 | 0.93 | −0.1 | 1.9 |

| 1991–2005 | −0.99 | −1.6 | −0.4 |

| Japan | |||

| 1963–1978 | 2.40 | 2.0 | 2.8 |

| 1978–1990 | 1.47 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| 1990–1997 | 3.11 | 2.2 | 4.0 |

| 1997–2006 | 1.34 | 0.9 | 1.8 |

| Korea | |||

| 1985–1993 | 5.62 | 3.9 | 7.4 |

| 1993–2006 | 2.63 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| Singapore | |||

| 1963–1990 | 1.13 | 0.5 | 1.8 |

| 1990–2006 | −1.50 | −2.4 | −0.6 |

| Taiwan | |||

| 1964–1987 | 1.95 | 1.5 | 2.4 |

| 1987–1996 | 4.63 | 3.3 | 6.1 |

| 1996–2007 | 0.89 | 0.2 | 1.4 |

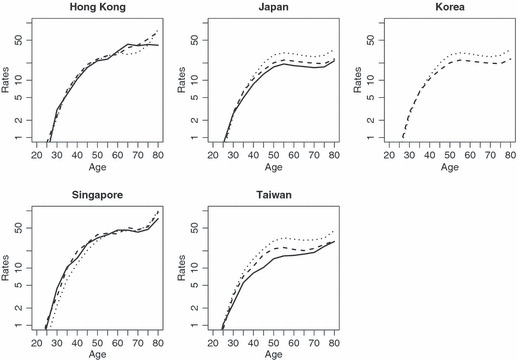

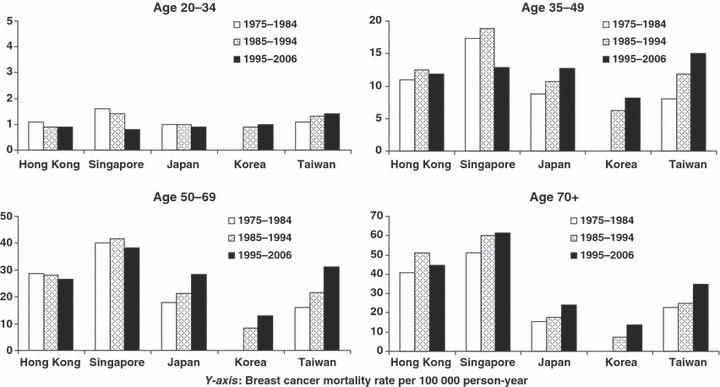

The patterns of age‐specific mortality curves during the last 30 years in Hong Kong and Singapore, which showed gradual increases with age, are different from those in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan where they are rather flat or declining after age 50 (Fig. 2). Figure 3 shows changes of mortality rates by age group. For women aged 20–34 years, the breast cancer mortality rate was low in all five study populations and tended to decrease in recent years except in Korea and Taiwan. For women aged 35–49 and 50–69 years, the rate has been increasing significantly in recent years in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan but decreasing in Hong Kong and Singapore. For women aged ≥70 years, risk tended to increase, except in Hong Kong, where there was an estimated annual change of –3.0% (data not shown). We observed no statistically significant EAPC for four age groups over three calendar periods (two calendar periods for Korea) (Fig. 3) (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Age‐specific breast cancer mortality rates (per 100 000) in five study populations for calendar years 1975–1984 (continuous line), 1985–1994 (dashes), and 1995–2006 (dots).

Figure 3.

Breast cancer mortality by age group, period, and country/region. Y‐axis, breast cancer mortality rate per 100 000 person‐year.

Discussion

In this study, we compared and assessed the secular trends and patterns of age‐specific breast cancer mortality among five East Asian female populations. The overall breast cancer mortality in Hong Kong (1979–2005) and Singapore (1963–2006) showed increases up to 1990 and a slight reduction after that, but were not significant. Breast cancer mortality rates, however, increased steadily until 2006, in Japan with a slightly high EAPC in the early 1990s, in Korea with a highest EAPC between 1985–1993, and in Taiwan with a rather great increment from the mid‐1980s to the mid‐1990s.

In most Western countries, in contrast, breast cancer mortality increased until at least the 1980s.( 1 , 8 , 24 ) Mortality started to decline in the USA in 1989( 24 , 25 ) and in Yorkshire in the United Kingdom, from 1983 to 1998( 26 ) due in part to birth cohort effects for women born from the end of the 19th century to the mid‐1920s( 27 ); and the decrease is expected to continue in the current decade as a long‐term result of both mammography screening and improved medical intervention.( 26 )

In the present study, we observed a relatively high reduction in breast cancer mortality in Hong Kong and Singapore after 1995 except in women aged 70 + in Singapore. In contrast, increases of breast cancer mortality in women in all age groups, with a rather greater rising in women after age 50, were observed in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.

Many Asian studies observed that age‐specific incidence rates reached a peak at around age 50 and then declined with age and that it is mostly due to a birth‐cohort effect in which risk increases progressively from one generation to the next.( 6 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ) Furthermore, increases of incidence rates are anticipated with the ageing of the population in the present study populations. The shapes of age‐specific mortality curve in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan in women after age 50 are similar to those curves among estrogen‐receptor (ER)‐negative breast cancer in Western countries.( 34 , 35 ) In the 1990s, reported ER positivity among breast cancer patients in Asia was lower than in Western women( 36 ); however, an increased proportion of ER‐positive cases in Asian women in recent years was observed in a couple of studies.( 37 , 38 ) This pattern of mortality curve will, therefore, change to be more similar to the curves in Western women from shapes of age‐specific curve in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan to shapes in Hong Kong and Singapore.

Cancer risk discrepancies between various populations may reflect different levels of risk by birth cohort as well as differences in the detection and management of the disease.

In Hong Kong, more than 80% of breast cancer cases were detected in a symptomatic setting due to the lack of region‐wide breast cancer screening programs.( 39 , 40 ) However, the guidelines for surgeons in the management of symptomatic breast disease published in 1995 in the United Kingdom were widely used.( 41 ) During the 1990s, there were significant improvements in the concepts of the diagnosis services as well as in the treatment policy for primary breast cancer and services for breast cancer patient management (services which, especially in the surgical aspects, have reached quality standards).( 42 , 43 ) The overall utilization of breast conserving therapy (BCT) increased from 30% to 50% since the mid‐1990s.( 39 , 40 ) In the beginning of the 1990s, the overall survival of breast cancer was 83%.( 42 )

The Japanese Breast Cancer Society published evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of early stage breast cancer in Japanese women in 2000( 43 ) and brought out treatment guidelines for systemic adjuvant therapy of breast cancer in 2006.( 44 ) Since 2001, the adjusted proportion of breast conserving surgery in clinical practice has increased dramatically from 26.4% before the guidelines to 59.9% after their publication.( 45 )

In Korea, the Breast Cancer Society first published the practice recommendations of breast cancer in 2002 (2nd edition in 2006 and 3rd edition in 2008) (http://www.kbcs.or.kr). According to a nationwide survey to evaluate the chronological changes in Korean breast cancer characteristics from 1996 to 2004, there were continuous increases of the percentage of early stage breast cancer and asymptomatic cases incidentally detected at mammography screening. During the same period, a rise of BCT was observed from 18.7% to 41.9%.( 46 ) The proportion of early breast cancer (carcinoma in situ and stage I) increased from 24.2% in 1993 to 36.6% in 2002 in the national breast cancer incidence database and showed gradual increases of the 5‐year relative survival from 75.2% in 1993 to 83.5% in 1999 (overall survival by stage I, II, II, IV was 98.2%. 91.7%. 68.2%, 30.5%, respectively).( 6 )

In Singapore, a decline in breast cancer mortality was observed before the introduction of a national screening program.( 21 ) In a study conducted in the 1990s prior to the advent of the screening program in Singapore, 73% of breast cancer patients received adjuvant radiation therapy and 88% received some form of systemic therapy (chemotherapy or tamoxifen).( 47 ) In reflection of this intervention, the 5‐year survival of each patient stage (for stages I–IV, survival rates are 97%, 78%, 51%, and 13%, respectively), was equivalent to those from Western countries.( 48 , 49 )

In Taiwan, the overall survival of 1378 breast cancer patients (71.6% with ER and 22% in early onset cases under age 40) who were treated from 1995 to 2001 and were followed up until June 2007 was 89% (95% CI, 87% to 9%). Two‐thirds of the patients in this study showed 100% adherence to the quality indicators in the clinical protocols.( 50 ) Rather low proportions of BCT, despite the increases of performance of BCT from 17.6% of all eligible patients for surgery between 1990 and 1997( 51 ) to 28.6% in the mid‐2000s,( 52 ) were partially explained on the basis of more advanced disease at initial presentation and misperception of radiation therapy among Taiwanese compared to the practices for preserving breasts for women with breast cancer in the Western countries.( 53 )

Taken together, services for breast cancer patient management, especially in the surgical aspects, have reached the quality standards in the guidelines in Asian countries since the late 1990s( 45 , 54 ); however, non‐conformity with both chemo‐ and hormone therapy guidelines was associated with higher risk of death.( 55 )

Although secular changes in risk factors should be considered along with the effects of screening and therapies when interpreting mortality trends, population‐level changes in risk factors have not been well examined. Hormonal and reproductive risk factors such as early menarche, late menopause, low parity, late age of first live birth, low prevalence of breastfeeding, high fat intake, alcohol consumption, and little physical activity in Hong Kong,( 15 ) Japan,( 56 ) Korea,( 57 ) Singapore,( 58 ) and Taiwan( 59 , 60 , 61 ) are consistent with those already observed in Western populations.

We must also take into account sources of bias, such as errors in death certification, incidence registration, and cure rates.( 62 ) (1) Errors in death certification are likely to have been reduced over the past decades with the establishment of national healthcare systems in Japan,( 63 ) Hong Kong,( 64 ) Singapore,( 65 ) Korea,( 66 ) and Taiwan.( 67 ) The increased risk observed for women aged ≥70 years in all those areas except Hong Kong might not be due to such errors. (2) Errors of incidence registration have decreased due to improvements in cancer registration in Japan,( 68 ) Korea,( 69 ) and Taiwan,( 70 ) as well as in Hong Kong and Singapore, which have been publishing incidence rates with high quality since 1983 and 1968, respectively.( 71 ) The recent increases in incidence rates in Korea may be partly attributable to the expanded coverage provided by the improved registration system.( 6 ) (3) Errors in estimation of cure rates have changed as breast cancer prognosis has improved, both by advances in management and by early detection through mammography screening. Improvements in breast cancer survival were reported in Japan,( 72 , 73 ) Korea,( 6 , 74 ) and Singapore.( 75 ) In Taiwan, the attributable proportions for improved survival of breast cancer due to early detection and medical care were 77% and 23% respectively.( 60 ) Predominance of early onset and aggressive ER‐negative breast cancers may partially account for the high breast‐cancer mortality in Asian countries.( 76 ) With advances in medical care, women in populations we studied may receive similar medical care in spite of living under differing healthcare systems. (4) In terms of the validity of mortality data, the completeness of population coverage is estimated to be 100% in Japan, 93% in Korea, and <80% in Singapore( 77 ) (data are unavailable for Hong Kong and Taiwan). Any biases that resulted from incomplete coverage may have decreased as the time periods covered in the present study progressed. Error can also be caused by inaccurate population estimates.

In the early 1990s, after many European countries established screening programs,( 14 ) there was a sudden decline in breast‐cancer mortality. The decline was not likely attributable to the programs, however, because randomized prospective trials indicate that the effects of screening generally take at least 10 years to be reflected in mortality statistics.( 78 ) Mammography, which was introduced in the early 1980s, is recommended for breast cancer screening in all five study populations. Japan and Korea organized a breast cancer screening program in 2002 that combines mammography with clinical breast examination( 19 , 20 ); since that time, breast cancer mortality has increased. Taiwan implemented a stratified breast cancer screening program in 1995,( 79 ) and the mortality rate stopped increasing in the mid‐1990s. The mortality rate in Singapore decreased before the introduction of screening (mammography with clinical breast examination) in 2002.( 21 ) In Hong Kong, where screening is voluntary with no recommendation due to low incidence,( 22 ) breast cancer mortality tended to decrease slightly after 1990. The decline of mortality rates was more pronounced for women younger than 50 years and is likely to be attributed to improved treatments.( 80 )

It is difficult and too early to assess the impact of breast cancer screening among Asian populations with the current trends of breast cancer mortality. Breast cancer mortality trends are expected to maintain the secular trend for the next decade mainly as the prevalence of risk factors changes and population ages in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Early detection and treatment improvement will continue to reduce the mortality rates in Hong Kong and Singapore as observed in Western countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katiuska Veselinovic for assisting in the preparation of the manuscript and John Daniel for manuscript editing.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res 2004; 6: 229–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang L, Parkin DM, Li L, Chen Y. Time trends in cancer mortality in China: 1987–1999. Int J Cancer 2003; 106: 771–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang L, Parkin DM, Li LD, Chen YD, Bray F. Estimation and projection of the national profile of cancer mortality in China: 1991–2005. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 2157–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qiu D, Katanoda K, Marugame T, Sobue T. A Joinpoint regression analysis of long‐term trends in cancer mortality in Japan (1958–2004). Int J Cancer 2009; 124: 443–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi Y, Kim YJ, Shin HR, Noh DY, Yoo KY. Long‐term prediction of female breast cancer mortality in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2005; 6: 16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JH, Yim SH, Won YJ et al. Population‐based breast cancer statistics in Korea during 1993–2002: incidence, mortality, and survival. J Korean Med Sci 2007; 22 (Suppl): S11–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chie WC, Chen CF, Lee WC, Chen CJ, Lin RS. Age‐period‐cohort analysis of breast cancer mortality. Anticancer Res 1995; 15: 511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beral V, Hermon C, Reeves G, Peto R. Sudden fall in breast cancer death rates in England and Wales. Lancet 1995; 345: 1642–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hermon C, Beral V. Breast cancer mortality rates are levelling off or beginning to decline in many western countries: analysis of time trends, age‐cohort and age‐period models of breast cancer mortality in 20 countries. Br J Cancer 1996; 73: 955–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Collette HJ, Day NE, Rombach JJ, De Waard F. Evaluation of screening for breast cancer in a non‐randomised study (the DOM project) by means of a case‐control study. Lancet 1984; 1: 1224–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Verbeek AL, Hendriks JH, Holland R, Mravunac M, Sturmans F, Day NE. Reduction of breast cancer mortality through mass screening with modern mammography. First results of the Nijmegen project, 1975–1981. Lancet 1984; 1: 1222–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tabar L, Fagerberg CJ, Gad A et al. Reduction in mortality from breast cancer after mass screening with mammography. Randomised trial from the Breast Cancer Screening Working Group of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Lancet 1985; 1: 829–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frisell J, Glas U, Hellstrom L, Somell A. Randomized mammographic screening for breast cancer in Stockholm. Design, first round results and comparisons. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1986; 8: 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shapiro S, Coleman EA, Broeders M et al. Breast cancer screening programmes in 22 countries: current policies, administration and guidelines. International Breast Cancer Screening Network (IBSN) and the European Network of Pilot Projects for Breast Cancer Screening. Int J Epidemiol 1998; 27: 735–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leung AW, Mak J, Cheung PS, Epstein RJ. Evidence for a programming effect of early menarche on the rise of breast cancer incidence in Hong Kong. Cancer Detect Prev 2008; 32: 156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang SC. The Singapore National Breast Screening Programme: principles and implementation. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2003; 32: 466–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang CS, Chang KJ, Shen CY. Breast cancer screening in Taiwan and China. Breast Dis 2001; 13: 41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lai MS, Yen MF, Kuo HS, Koong SL, Chen TH, Duffy SW. Efficacy of breast‐cancer screening for female relatives of breast‐cancer‐index cases: Taiwan multicentre cancer screening (TAMCAS). Int J Cancer 1998; 78: 21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morimoto T, Okazaki M, Endo T. Current status and goals of mammographic screening for breast cancer in Japan. Breast Cancer 2004; 11: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoo KY. Cancer control activities in the Republic of Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2008; 38: 327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yeoh KG, Chew L, Wang SC. Cancer screening in Singapore, with particular reference to breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening. J Med Screen 2006; 13 (Suppl 1): S14–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lui CY, Lam HS, Chan LK et al. Opportunistic breast cancer screening in Hong Kong; a revisit of the Kwong Wah Hospital experience. Hong Kong Med J 2007; 13: 106–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Cancer Institute . Joinpoint Regression Program version 3.3 (Online). National Cancer Institute, 2008. [Cited 10 Jul 2008.] Available from URL: http://srab.cancer.gov/joinpoint/. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chu KC, Tarone RE, Kessler LG et al. Recent trends in U.S. breast cancer incidence, survival, and mortality rates. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996; 88: 1571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weir HK, Thun MJ, Hankey BF et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95: 1276–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pisani P, Forman D. Declining mortality from breast cancer in Yorkshire, 1983–1998: extent and causes. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 652–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reynolds T. Declining breast cancer mortality: what’s behind it? J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 750–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leung GM, Thach TQ, Lam TH et al. Trends in breast cancer incidence in Hong Kong between 1973 and 1999: an age‐period‐cohort analysis. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 982–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Minami Y, Tsubono Y, Nishino Y, Ohuchi N, Shibuya D, Hisamichi S. The increase of female breast cancer incidence in Japan: emergence of birth cohort effect. Int J Cancer 2004; 108: 901–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seow A, Duffy SW, McGee MA, Lee J, Lee HP. Breast cancer in Singapore: trends in incidence 1968–1992. Int J Epidemiol 1996; 25: 40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chia KS, Reilly M, Tan CS et al. Profound changes in breast cancer incidence may reflect changes into a Westernized lifestyle: a comparative population‐based study in Singapore and Sweden. Int J Cancer 2005; 113: 302–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen YC, Chang CJ, Hsu C, Cheng CC, Chiu CF, Cheng AL. Significant difference in the trends of female breast cancer incidence between Taiwanese and Caucasian Americans: implications from age‐period‐cohort analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005; 14: 1986–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jin F, Devesa SS, Chow WH et al. Cancer incidence trends in urban Shanghai, 1972–1994: an update. Int J Cancer 1999; 83: 435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yasui Y, Potter JD. The shape of age‐incidence curves of female breast cancer by hormone‐receptor status. Cancer Causes Control 1999; 10: 431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anderson WF, Chu KC, Chang S, Sherman ME. Comparison of age‐specific incidence rate patterns for different histopathologic types of breast carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004; 13: 1128–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lim SE, Back M, Quek E, Iau P, Putti T, Wong JE. Clinical observations from a breast cancer registry in Asian women. World J Surg 2007; 31: 1387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Suzuki T, Matsuo K, Tsunoda N et al. Effect of soybean on breast cancer according to receptor status: a case‐control study in Japan. Int J Cancer 2008; 123: 1674–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin CH, Liau JY, Lu YS et al. Molecular subtypes of breast cancer emerging in young women in Taiwan: evidence for more than just westernization as a reason for the disease in Asia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18: 1807–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chan WF, Cheung PS, Epstein RJ, Mak J. Multidisciplinary approach to the management of breast cancer in Hong Kong. World J Surg 2006; 30: 2095–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yau TK, Soong IS, Sze H et al. Trends and patterns of breast conservation treatment in Hong Kong: 1994–2007. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 1:74 (1): 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. British Assocition of Surgical Oncololgy . Guidelines for surgeons in the management of symptomatic breast disease in the United Kingdom. Eur J Surg Oncol 1995; 21 (Suppl A): 1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chow LW, Au GK, Poon RT. Breast conservation therapy for invasive breast cancer in Hong Kong: factors affecting recurrence and survival in Chinese women. Aust N Z J Surg 1997; 67: 94–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Japanese Breast Cancer Society . Practice guideline; breast‐conserving surgery. Jpn J Breast Cancer 2000; 15: 147–56. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Watanabe T, Mukai H. [Treatment guidelines for systemic adjuvant therapy of breast cancer]. Nippon rinsho 2006; 64: 419–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fukuda H, Imanaka Y, Ishizaki T, Okuma K, Shirai T. Change in clinical practice after publication of guidelines on breast cancer treatment. Int J Qual Health Care 2009; 21: 372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ahn SH, Yoo KY. Chronological changes of clinical characteristics in 31,115 new breast cancer patients among Koreans during 1996–2004. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006; 99: 209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brody JG, Moysich KB, Humblet O, Attfield KR, Beehler GP, Rudel RA. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer: epidemiologic studies. Cancer 2007; 109: 2667–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Osteen RT, Karnell LH. The National Cancer Data Base report on breast cancer. Cancer 1994; 73: 1994–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sant M, Allemani C, Berrino F et al. Breast carcinoma survival in Europe and the United States. Cancer 2004; 100: 715–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cheng SH, Wang CJ, Lin JL et al. Adherence to quality indicators and survival in patients with breast cancer. Med Care 2009; 47: 217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cheng SH, Tsou MH, Liu MC et al. Unique features of breast cancer in Taiwan. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000; 63: 213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chang JT, Chen CJ, Lin YC, Chen YC, Lin CY, Cheng AJ. Health‐related quality of life and patient satisfaction after treatment for breast cancer in northern Taiwan. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007; 69: 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cheng SH, Chen CM, Jian JM et al. Breast‐conserving surgery and radiotherapy for early breast cancer. J Formosa Med Assoc 1996; 95: 372–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cheung KL. Management of primary breast cancer in Hong Kong – can the guidelines be met? Eur J Surg Oncol 1999; 25: 255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yun YH, Park SM, Noh DY et al. Trends in breast cancer treatment in Korea and impact of compliance with consensus recommendations on survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007; 106: 245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin Y, Kikuchi S, Tamakoshi K et al. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in Japanese women. Int J Cancer 2005; 116: 779–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yoo KY, Kang D, Park SK et al. Epidemiology of breast cancer in Korea: occurrence, high‐risk groups, and prevention. J Korean Med Sci 2002; 17: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee HP, Gourley L, Duffy SW, Esteve J, Lee J, Day NE. Risk factors for breast cancer by age and menopausal status: a case‐control study in Singapore. Cancer Causes Control 1992; 3: 313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang PS, Yang TL, Liu CL, Wu CW, Shen CY. A case‐control study of breast cancer in Taiwan – a low‐incidence area. Br J Cancer 1997; 75: 752–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chie WC, Chang YH, Chen HH. A novel method for evaluation of improved survival trend for common cancer: early detection or improvement of medical care. J Eval Clin Pract 2007; 13: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lee MM, Chang IY, Horng CF, Chang JS, Cheng SH, Huang A. Breast cancer and dietary factors in Taiwanese women. Cancer Causes Control 2005; 16: 929–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Doll R, Peto R. The causes of cancer: quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. J Natl Cancer Inst 1981; 66: 1191–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fukawa T. Public Helath Insurance in Japan. Washington D.C. (WA): World Bank Institute, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Leung GM, Wong IO, Chan WS, Choi S, Lo SV. The ecology of health care in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61: 577–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ministry of Health Singapore . Healthcare system (Online). Ministry of Health Singapore, 2007. [Cited 23 Apr 2009]; [about 2p.] Available from URL: http://www.moh.gov.sg/mohcorp/hcsystem.aspx?id=102. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan 2009; 24: 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cheng TM. Taiwan’s new national health insurance program: genesis and experience so far. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003; 22: 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tomotaka S. Cancer registration and cancer control in Japan. Paper presented at: Annual Scientific meeting of the International Association of Cancer Registries; 2008 Nov 17‐21; Sydney, Australia.

- 69. Shin HR, Won YJ, Jung KW et al. Nationwide cancer incidence in Korea, 1999–2001; First result using the National Cancer Incidence Database. Cancer Res Treat 2005; 37: 325–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Taiwan Cancer Registry . Cancer statistics (Online). Taiwan Cancer Registry, 2008. [Cited Oct 2008.] Available from URL: http://crs.cph.ntu.edu.tw/main.php?Page=N2. [Google Scholar]

- 71. International Agency for Research on Cancer . CancerMondial (Online) [Cited Oct 2008.] International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2008. Available from URL: http://www‐dep.iarc.fr/. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tsukuma H, Ajiki W, Ioka A, Oshima A. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed between 1993 and 1996: a collaborative study of population‐based cancer registries in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2006; 36: 602–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ito Y, Ohno Y, Rachet B, Coleman MP, Tsukuma H, Oshima A. Cancer survival trends in Osaka, Japan: the influence of age and stage at diagnosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2007; 37: 452–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jung KW, Yim SH, Kong HJ et al. Cancer survival in Korea 1993–2002: a population‐based study. J Korean Med Sci 2007; 22 (Suppl): S5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chia KS, Du WB, Sankaranarayanan R, Sankila R, Seow A, Lee HP. Population‐based cancer survival in Singapore, 1968 to 1992: an overview. Int J Cancer 2001; 93: 142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ahn SH, Son BH, Kim SW et al. Poor outcome of hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer at very young age is due to tamoxifen resistance: nationwide survival data in Korea – a report from the Korean Breast Cancer Society. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 2360–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. World Health Organization . Health statistics and health information systems (Online). Switzerland: WHO, 2009. [Cited 23 Apr 2009.] Available from URL: http://who.int/healthinfo/morttables/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jatoi I, Miller AB. Why is breast‐cancer mortality declining? Lancet Oncol 2003; 4: 251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wu GH, Chen LS, Chang KJ et al. Evolution of breast cancer screening in countries with intermediate and increasing incidence of breast cancer. J Med Screen 2006; 13 (Suppl 1): S23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hery C, Ferlay J, Boniol M, Autier P. Changes in breast cancer incidence and mortality in middle‐aged and elderly women in 28 countries with Caucasian majority populations. Ann Oncol 2008; 19: 1009–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]