Abstract

The present study was focused on identifying cancer cell-specific internalizing ligands using a new kind of phage display library in which the linear or cysteine-constrained random peptides were at amino-terminus fusion to catalytically active P99 β-lactamase molecules. The size and quality of libraries were comparable to other reported phage display systems. Several cancer cell-specific binding and internalizing β-lactamase-peptide fusion ligands were isolated by selecting these libraries on the live BT-474 human breast cancer cells. The identified ligands shared several significant motifs, which showed their selectivity and possible binding to some common cancer cell targets. The β-lactamase fusion made the whole process of clone screening efficient and simple. The ligands selected from such libraries do not require peptide synthesis and modifications, and can be used directly for applications that require ligand tracking. In addition, the selected β-lactamase-peptide ligands have a potential for their direct use in targeted enzyme prodrug therapy. The cancer-specific peptides can also be adopted for other kinds of targeted delivery protocols requiring cell-specific affinity reagents. This is first report on the selection of cell-internalized enzyme conjugates using phage display technology, which opens the possibility for new fusion libraries with other relevant enzymes.

Keywords: cancer, cell-internalized ligands, enzyme prodrug therapy, phage display, β-lactamase

Introduction

Cytotoxic chemotherapies, which work primarily through the inhibition of cell division, have become established as one of the major therapeutic modalities in cancer. The major problems associated with this treatment include lack of selectivity for tumor cells over normal cells, insufficient drug concentrations in tumors, systemic toxicity and development of drug resistant cancer cells (Young, 1990; Kirsner, 2003). Cancer researchers today focus on developing new types of cancer treatments that use drugs or other substances to identify and kill cancer cells while doing very little or no damage to normal healthy cells. It is believed that an ability to home in on cancer cells makes chemotherapy both more effective and less likely to cause side effects. A variety of strategies are being evaluated to achieve this goal (Allen, 2002; Crown and Pegram, 2003; Neri and Bicknell, 2005; Pegram et al., 2005; Krag et al., 2006). One promising strategy is to exploit the differences in molecular composition of the cell surfaces of cancer and normal cells for developing targeted anti-cancer drugs. The altered cell surface chemistry plays a critical role in responding to external signals for cancer cell growth and survival and in interacting with host tissue elements for cancer cell dissemination and metastasis. Researchers have focused on developing ligands that specifically bind to cancer cells and exert therapeutic effects of their own or guide a targeted delivery of a therapeutic agent (cytotoxic drug, gene, radionuclide or enzyme) to the tumor site (Fuchs and Bachran, 2009). Some of these strategies rely on the ligands to bind the surface receptor in a manner that induces receptor-mediated endocytosis, resulting in the delivery of a therapeutic agent into the cytosol.

The screening and selection of peptides and antibodies by phage display technology is increasingly used to identify ligands that interact specifically and with high affinity with a particular target. Phage displayed libraries have been successfully used to identify ligands against an incredibly diverse population of targets including those associated with cancers (Begent et al., 1996; Smith and Petrenko, 1997; Szardenings et al., 1997; Desai et al., 1998; Shukla and Krag, 2005a,b; Brissette et al., 2006). Products derived from phage display technology have now been approved by the FDA for human use and are available as commercial agents (Shukla and Krag, 2006). In the present study, we identified several cancer cell binding and internalizing ligands using a new kind of phage display library in which the random peptides are at amino-terminus fusion to the catalytically active β-lactamase (β-lactam hydrolase, E.C. no 3.5.2.6) molecules. This is the first time the selection of cell-internalized ligands that are conjugated to a functional enzyme is being reported. β-Lactamase being an excellent reporter helped the tracking of fusion peptide ligands in their cell binding and internalizing screenings. The ligands selected from these libraries have a potential for their direct use in the targeted enzyme prodrug therapy, which is based on the concept that a systemically administered non-toxic prodrug can be converted locally to high concentrations of a cytotoxic drug by an enzyme predominantly present at the tumor site (Bagshawe, 2009).

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human breast cancer and non-cancer cell lines and 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells used in this study were obtained from the American-type culture collection (ATCC; Manassas, Virginia). Human breast cancer SUM159 cell line was obtained from Dr Stephen Ethier (Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI). Human breast cancer BT-474 cells were grown in 90% ATCC Hybri-Care medium supplemented with 1.5 g/l sodium carbonate and 10% fetal bovine serum. Non-cancer breast fibroblast HS 578Bst cells were cultured in the medium described for BT-474 with an addition of mouse EGF (30 ng/ml). Human non-cancer breast epithelial MCF-10A cells were propagated in Clonetics® Mammary Epithelial Basal Medium® containing bovine pituitary extract (52 µg/ml), hydrocortisone (0.5 µg/ml), hEGF (10 ng/ml), insulin (5 µg/ml) and cholera toxin (100 ng/ml). The basal medium and additives for MCF 10A cells were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, Maryland). Cholera toxin, prepared from Vibrio cholerae-type Inaba 569B, was obtained from Calbiochem (EMD Biosciences, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Another non-cancer breast epithelial MCF 12A cell line was propagated in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F12 medium (ATCC) containing hEGF (20 ng/ml), cholera toxin (100 ng/ml), bovine insulin (10 µg/ml), hydrocortisone (0.5 µg/ml) and 5% horse serum. Breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-361 and MDA-MB-468 were cultured in Leibovitz's L-15 medium (ATCC) containing 10 and 20% fetal bovine serum, respectively. Breast cancer MCF-7 and HS 578T cell lines were grown in Eagle's MEM and DMEM (ATCC), respectively, containing 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin and 10% fetal bovine serum. Breast cancer T-47D cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (ATCC) containing 0.2 units/ml bovine insulin and 10% fetal bovine serum. SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells were grown in modified McCoy's 5a medium (ATCC) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Breast cancer SUM159 cell line was propagated in Ham's F12 media (GIBCO) containing glutamine, insulin (5 µg/ml), hydrocortisone (2 µg/ml) and 5% fetal bovine serum. Mouse fibroblast 3T3 cells were grown in DMEM (ATCC) containing 10% bovine calf serum. The cells were cultured at 37°C in a humid atmosphere with 5% CO2.

β-lactamase-peptide fusion libraries

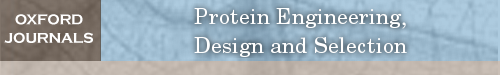

The phagemid vector that expresses the Enterobacter cloacae P99 cephalosporinase (P99 β-lactamase) as an N-terminal fusion to pIII protein was used for the construction of the libraries. A schematic representation of the phagemid vector design and characteristics are presented in Fig. 1. The linear dodecapeptide (X12) and cysteine-constrained decapeptide (CX10C) libraries were cloned at the N-terminal position of β-lactamase molecules, between the signal peptide and the enzyme protein. The half-site cloning method was employed for constructing the β-lactamase fusion libraries using the nnk-scheme of randomization (Cwirla et al., 1990). The nnk-scheme (where, N presents A, G, C or T and K presents T or G) is an extensively used conventional method in library construction, which eliminates the potential for opal (tga) and ochre (taa) stop codons and still encodes all 20 amino acids using 32 codons. The construction of the libraries were done using the approach reported earlier (Shukla and Krag, 2010). In order to avoid clones without an insert, the randomization was achieved in two steps. In the first step, oligonucleotides containing the stop-codons were cloned at the place of intended randomization. In the second step, the vector containing the stop-codons was purified, digested with SpeI and AgeI and cloned with the 5′-phosphorylated oligonucleotides with the random region. The oligonucleotides used for the linear library construction were 5′ctagtcgttcctttctattctcactctgct-nnk12-ggtggaggttcgaca3′ (forward), 5′agcagagtgagaatagaaaggaacga3′ and 5′ccggtgtcgaacctccac3′ (both complementary). The oligonucleotides for the cysteine-constrained library were the same, except that in the forward strand cysteine codons replaced the 1st and 12th nnk (tgt-nnk10-tgc). The gel-purified oligonucleotides were obtained from Bio-Synthesis (Lewisville, Texas). TG1 bacterial cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were transformed using an electroporator (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with 0.1-cm gap electroporation cuvettes at 1700 V. The total number of primary clones was determined by plating the transformed bacteria on LB/agar containing only chloramphenicol (10µg/ml) without a β-lactam antibiotic. However, the β-lactamase-active primary clones were determined by plating the bacteria in the presence of 0.1 µg/ml cefotaxime (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) and chloramphenicol (10 µg/ml). Cefotaxime is a β-lactam antibiotic that allows the growth of only those clones that produce a functional β-lactamase protein. The phage libraries were produced by super-infection of the β-lactamase active clones with KM13 helper phage (Kristensen and Winter, 1998).

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic presentation of phagemid vector design. The vector expressed random peptide libraries at the amino-terminus of P99 β-lactamase, linked through Gly-Gly-Gly-Ser linker. The C-terminal end of P99 β-lactamase had FLAG and 6xHis tags, which were connected to pIII protein with the protease-cleavable linker (PAGLSEGSTIEGRGAHE). pIII signal peptide was used for periplasmic translocation of β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein. The vector has T7, SP6 and lac promoters. CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; Amber stop, amber stop codon (tag); pIII signal peptide, oligonucleotide sequence that encode the peptide; P lac, lac promoter; gIII, pIII protein gene; f1 Ori, f1 origin of replications from filamentous bacteriophage; (B) This vector in suppressor host TG1 E. coli, with the help of KM13 helper phage, generated phage particles displaying β-lactamase-random peptide as an N-terminal fusion protein to phage coat pIII. In non-suppressor strain Top10 E. coli, which recognizes the amber codon, the same vector expressed free β-lactamase fusion proteins with a random peptide library at the N-terminal end and FLAG and 6xHis tags at the C-terminal end.

Selection of cancer cell-binding and internalizing ligands

Human breast cancer BT-474 cells and human non-cancer epithelial MCF 10A cells were plated in a 35 mm CellBIND® dish and T25 flask (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) and allowed to grow to about 80% confluency. The mixture (1:1) of phage particles (∼1×1012 colony-forming units, cfu) from both linear and cysteine-constrained libraries was mixed with complete medium containing mammalian protease inhibitor cocktail (20 µl/ml; Sigma Chemical Co.), and subtracted for plastic-binding clones by incubation in a CellBIND® flask. The plastic-subtracted libraries were added to the MCF 10A cells grown in monolayer and incubated for 2 h at 4°C for the negative subtraction of the clones binding to normal breast epithelial cells. Prior to the biopanning, the medium of BT-474 cells was renewed and incubated with 100 µM chloroquine (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 30 min at 37°C. In the next step, the BT-474 monolayer was incubated with MCF 10A-subtracted phage libraries for 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere (Becerril et al., 1999). The cells were washed six times with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline with Ca2+ and Mg2+ (DPBS; Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) and incubated with 50 mM glycine buffer, pH 2.8 (containing 154 mM NaCl) for 15 min at room temperature. Following a wash with DPBS, the cells were trypsinized. The cells were collected in 1.5-ml tubes and washed two times in PBS by centrifugation. The cell pellet was lysed in 100 mM triethylamine for 10 min and neutralized with 1 M Tris (pH 7). TG1 Escherichia. coli culture grown to an OD600 of 0.4 was infected with the eluted phage. A small portion of this culture was used for the phage titration. The rest of the culture was centrifuged and plated on LB/agar plates (150 mm) containing chloramphenicol (10 µg/ml) and cefotaxime (0.1 µg/ml). The colonies were scraped in 1 ml of 15% glycerol in LB medium and 50 µl of this stock was amplified for the phage production following KM13 helper phage super infection (Kristensen and Winter, 1998). The phage preparation from the first round of panning was used as an input for the second round of panning. A total of three rounds of panning were conducted. The second and third rounds of panning were conducted essentially the same way as described above, except for an omission of the chloroquine incubation step.

Sample preparation for β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein

The purified phagemids from the phage-infected bacterial culture following the third round of panning were used for the electro-transformation of competent TOP10 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (Shukla et al., 2007). The β-lactamase active clones were selected on LB/agar plates containing cefotaxime (0.1 µg/ml) and chloramphenicol (10 µg/ml). TOP10 is a non-suppressor E. coli strain that recognizes amber stop codon (tag) at the 3′ end of 6xHis-tag sequence; therefore, it generates a pIII-independent fusion protein (Hayashi et al., 1995). The β-lactamase in the fusion proteins are linked to a peptide at the N-terminal end, and the FLAG and hexahistidine tags at the C-terminal end. Isolated individual colonies were randomly selected and amplified in 2xYT medium with shaking at 260 rpm for 30 h at 30°C. The cultures were centrifuged in cold at 3000g for 10 min. The bacterial pellets were suspended in 2× bacterial protein extraction reagents (B-PER II™, Invitrogen) containing bacterial protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Chemical Co.) and frozen at −80°C. The samples were thawed and incubated with slow shaking at room temperature for 90 min (Shukla et al., 2007). The bacterial lysates were centrifuged at 15 000g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants were used for β-lactamase purification, binding screening and β-lactamase protein and enzyme activity assays. Nickel-sepharose columns (GE Health Care, Bio-sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) were used for the purification of 6xHis-tagged peptide-β-lactamase fusion proteins.

β-lactamase enzyme assay

The β-lactamase enzyme was assayed by colorimetric and fluorometric procedures as described earlier (Shukla et al., 2007; Shukla and Krag, 2009). Briefly, the β-lactamase activity of different samples were assayed in a 96-well microplate by mixing 20 µl of enzyme preparation with 100 µl solution of either nitrocefin (100 µg/ml; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) (Duez et al., 1982) or soluble type Fluorocillin™ Green (10 µg/ml; Invitrogen) made in PBS. The changes in the absorbance (490 nm, nitrocefin) or fluorescence (Ex 495 nm/Em 525 nm, fluorocillin) were measured at 2-min intervals for 10 min using Synergy-HT microplate reader (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT). A linear range of both assays were determined by using different amounts of β-lactamase enzyme. In the present investigation, nitrocefin substrate was used for the sample normalizations and Fluorocillin™ Green for clone-binding studies.

ELISA of β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein

The different dilutions of bacterial lysate samples (100 µl) were incubated overnight in 96-well Ni-NTA microplates (HisSorb™; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in cold. The next day, wells were washed four times with PBST and blocked with 1% casein (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 1 h at room temperature. The wells were washed two times with PBS and incubated with 20 000-times diluted 100 µl FLAG antibody-HRP conjugate (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 1 h at room temperature. The wells were washed four times with PBST and two times with PBS. The horse-radish peroxidase activity was measured using SuperSignal® ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The luminescence was read using GloRunner™ microplate luminometer (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA).

Clone screening for cell binding

The randomly selected clones were studied for their binding to live BT-474, MCF 10A and 3T3 cells. Thirty thousand cells of each cell line were plated in a 96-well CellBind® culture plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) and incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. The next day, the cells were shifted to DMEM medium containing 1 mg/ml BSA and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. The medium was removed and 100 µl normalized β-lactamase samples were added to the wells. The normalization was achieved by diluting the samples with DPBS containing BSA (1 mg/ml) and mammalian protease inhibitor cocktail so that 100 µl of each sample has the enzyme activity equivalent to 6 OD change per min, when assayed using nitrocefin substrate by the procedure described above. The samples of wild-type β-lactamase and those prepared from unselected library clones were also included as negative controls. The cells were incubated for 2 h at room temperature and washed five times with DPBS. The enzyme activities of cell-bound β-lactamase were assayed fluorometrically (Ex 495 nm/Em 525 nm) using a fluorescence plate reader as described earlier.

The cell-binding studies with several cancer and non-cancer cells were also conducted by the microscopic technique (Shukla and Krag, 2010). The procedure was the same as described above, except that the cell-bound β-lactamase was visualized (Ex 345 nm/Em 530 nm) with the help of the precipitating type Fluorocillin™ Green substrate (Invitrogen) using Nikon TE2000-U inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corp., Kanagawa, Japan).

Microscopic studies for cell internalized clones

Immunofluorescence localization.

The cancer and non-cancer cells were grown on poly-d-lysine-coated 12 mm round coverslips (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) in 24-well culture plates (Corning Incorporated) to ∼50% confluency. The cells were incubated in 180 µl of renewed medium for 2 h prior to the addition of selected clones. Twenty microliters of normalized purified protein samples (10 µg/ml) of β-lactamase-peptide clones in PBS containing 1 mg BSA/ml and mammalian protease inhibitor cocktail were added to medium. The cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After washing three times with DPBS, the cells were incubated with 50 mM glycine–HCl buffer (containing 154 mM NaCl), pH 2.8, for 15 min at room temperature. After three additional DPBS washes, the cells were fixed in 2% buffered paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with PBS and permeabilized with acetone for 10 min at −21°C. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 1% BSA in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. The β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein was detected with Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated anti-6xHis tag antibody. The cells were also exposed to DAPI for a nuclear staining. After a primary analysis with Nikon TE2000-U inverted fluorescence microscope, the coverslips were removed from the wells and inverted on a slide on fluorescence mounting medium (Dako North America, Inc., Carpinteria, CA) for taking optical confocal sections (Z-series) using Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Germany). In order to show that the cell internalization of the selected β-lactamase proteins is mediated by their fusion peptides, certain internalization studies in BT-474 cells were also conducted in the presence of 10 µM of corresponding synthetic peptides or control random peptides (Bio-Synthesis, Lewisville, TX).

β-lactamase enzyme activity-based localization.

The cell internalization of β-lactamase-peptide clones was also studied by detecting the intracellular β-lactamase enzyme activity using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based substrate CCF4-AM (Invitrogen). The esterified substrate readily enters the cells and gets cleaved by endogenous cytoplasmic esterase producing negatively charged CCF4, which is retained in the cytosol. This substrate consists of a cephalosporin core linking a 7-hydroxycoumarin to a fluorescein, which upon excitation at 409 nm results in FRET to the fluorescein, emitting green fluorescence signals (520 nm). β-Lactamase-induced cleavage of the cephalosporin spatially separates the two dyes and disrupts FRET, so that excitation of the coumarin at 409 nm now produces a blue fluorescence signal (450 nm). The BT-474 and MCF 10A cells were grown to ∼50% confluency in a 96-well cell CellBind® culture plates (Corning Incorporated) and treated in the same way as described above in the immunolocalization method. However, after the β-lactamase-peptide protein incubation step, the membrane bound fusion molecules were stripped with 50 mM carbonate buffer, pH 12 (containing 154 mM NaCl), instead of a low pH glycine buffer which interfered with the cell-loading of CCF4-AM in the next step. The treatment with 2 M urea, 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone or 2 M NaCl were also found to be compatible with the cell-loading step. The washed cells were loaded with CCF4-AM dye (2 µg/ml DPBS, containing 12.5 mM anion transport inhibitor probenecid) for 45 min at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with DPBS and observed under Nikon TE2000-U inverted fluorescence microscope using a filter cube with an excitation filter of 405 ± 10 nm, an emission filter of 435 nm-long pass that allowed transmission of both green and blue fluorescence light, and a dichroic mirror that blocked the emission light <425 nm.

DNA sequence analysis and bioinformatics

During the construction of the libraries, the vector DNA was sequenced at each step of cloning using appropriate primers. The randomized DNA inserts in the unselected libraries and cell-binding β-lactamase fusion clones were also sequenced. The plasmids purified with QIAprep® miniprep columns (Valencia, CA) were subjected to cycle sequencing reactions using BigDye® Terminator version 3.1 kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The Vermont Cancer Center DNA Analysis Facility at the University of Vermont carried out an automated DNA sequencing using ABI Prism® 3130xl Genetic Analyzer. The translated amino acid sequences of N-terminal fusion peptides in BT-474 cell-binding and internalizing β-lactamase clones were searched for significant motifs using the IBM Sequence Pattern Discovery Tool software program based on TEIRESIAS algorithm (Rigoutsos and Floratos, 1998). The frequency and diversity of amino acids distribution in peptide inserts from the clones of both libraries were determined by using receptor ligands contacts (RELIC) program (Mandava et al., 2004).

Results

The sizes of linear and cysteine-constrained β-lactamase fusion libraries as determined by the numbers of their primary β-lactamase-active clones were ∼5 × 107 and ∼6 × 107, respectively. The DNA analysis of randomly picked clones showed an acceptable overall and positional diversity of different amino acids in the random region of both linear and cysteine-constrained libraries that are comparable to other reported phage-displayed libraries (Rodi et al., 2002; Shukla et al., 2007). All the analyzed clones showed the presence of fusion peptides in frame and their purified phage particles and free β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein samples exhibited strong β-lactamase activities. The levels of β-lactamase protein levels (relative chemiluminescence units/ml), as determined by the ELISA, and the enzyme activities (OD change/min/ml) showed no significant differences in the expression yields and specific activities (ratio between OD change per minute per milliliter and relative chemiluminescence units per milliliter) of different fusion clones, and the values were comparable to the β-lactamase enzyme without fusion peptide (data not presented). The enzyme stability of the β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins as tested by assaying the β-lactamase activities of different clones following 4 h incubation at 37°C also did not differ significantly.

Biopanning and enrichment of cancer cell-internalized clones

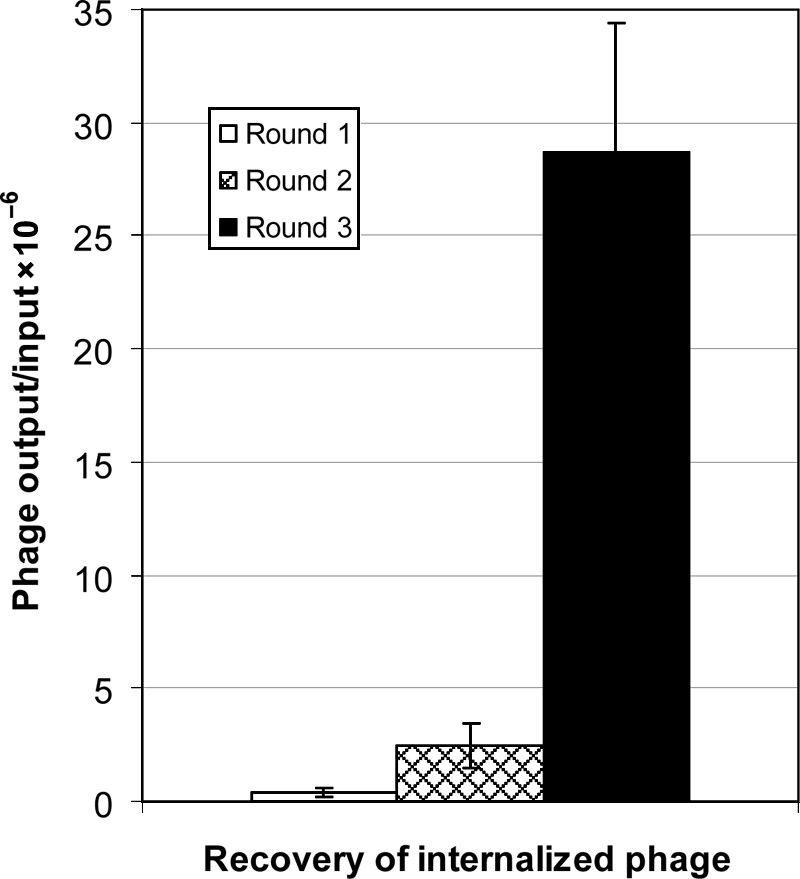

Three rounds of biopanning on live human breast cancer BT-474 cells were performed using β-lactamase-peptide fusion libraries, which were subtracted on the non-cancer human breast epithelial cells (MCF 10A). The consecutive rounds of biopanning showed enrichment in the internalized clones in BT-474 cells. The data presented in Fig. 2 shows ∼6-fold higher recovery of the cell-internalized clones in the second round, as compared with the first round of panning. The third round of panning produced a dramatic increase of ∼76-fold recovery as determined by the ratio of output/input of phage. The numbers of cell-internalized (output) phage particles were determined by the phage titration of BT-474 cell lysates following each round of the biopanning.

Fig. 2.

Enrichment of cell-internalized clones at subsequent rounds of biopanning. The phage enrichments were evaluated by comparing the phage recovery ratios (output/input phage) in different rounds of the biopanning. The phage were quantified as cfu using biological titration method. Each bar represents the ratio ± SE of three determinations.

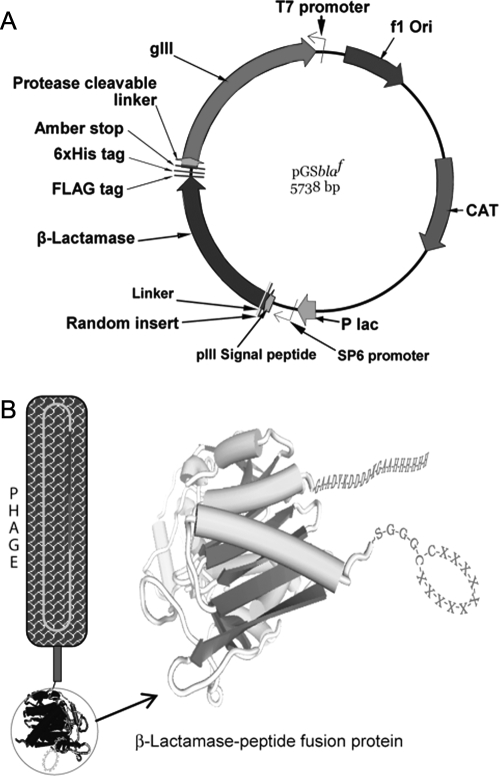

Clone screening for identification of cancer cell-binding soluble β-lactamase-peptide fusions

The data presented in Fig. 3 show the bindings of soluble β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins that were prepared from 62 randomly selected clones following the third round of panning on the live breast cancer BT-474 cells. The selected β-lactamase fusion proteins were studied for their comparative binding to live BT-474, non-cancer breast epithelial MCF 10A cells and unrelated 3T3 cells. Twenty of the 62 screened fusions, about one-third, showed significantly higher binding to the BT-474 cells against which they were panned, in comparison to the MCF 10A cells and 3T3 cells. The mouse fibroblast 3T3 cells were used as an irrelevant negative cell line control. The cancer cell binding of these fusions was also significantly higher as compared with the β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins from a pool of unselected library clones and to the wild-type β-lactamase, which were used as negative fusion protein controls. The positive β-lactamase fusion proteins that bound to BT-474 cells did not show binding to well plastics or non-specific proteins, BSA and casein (data not presented).

Fig. 3.

Binding of β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins to live human breast cancer cells. Soluble fusions from 62 randomly selected clones following the third round of panning were screened for their binding to live BT-474 cells. The lysates used for the screening were normalized for their β-lactamase activity. The human non-cancer MCF 10A epithelial cells and mouse fibroblast 3T3 cell-line were used as negative control cells. The screening was based on assaying the cell-bound β-lactamase activities. A pool of peptide fusion proteins from the unselected library clones and wild-type β-lactamase (Wt-BLA; without fusion peptide) were used as negative fusion peptide controls. The bars represent β-lactamase activity as change in relative fluorescence unit (RFU)/min ± SE of three determinations. *P ≤ 0.05, significance of difference in the binding of fusion proteins to BT-474 cells in comparison to MCF 10A or 3T3 cells were determined using Student's t-test.

The peptide DNA segments of BT-474-binding clones were sequenced. The translated amino acid sequences of the β-lactamase fusion peptides and their frequency of occurrences among positive clones are presented in Table I. These β-lactamase clones are represented by their N-terminal fusion dodecapeptides. Among BT-474 cell binders, a total of 18 β-lactamase-peptide clones were unique. Seven of them came from the cysteine-constrained library and the rest from the linear. Two clones one each from the linear, LSVCVRGLLGCG (clone 201/212), and the cysteine-constrained, CGDGVWVGWVRC (clone 204/224), libraries appeared twice.

Table I.

Amino acid sequences of β-lactamase fusion linear dodecamer (X12) and cysteine-constrained decamer (CX10C) peptides that were found to bind live human breast cancer BT-474 cells

| Clone numbers | Amino acid sequences | Clone numbers | Amino acid sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| 201, 212 | LSVCVRGLLGCG | 228 | VWGVFGGCSQRP |

| 204, 224 | CGDGVWVGWVRC | 232 | LSVWMQGLSRSL |

| 208 | VCMNFVPAICRV | 235 | CGLGWCGVRWGC |

| 210 | KFLAYPSFFSRC | 240 | GGLHKDVCVAIF |

| 215 | LFMAGGSCYLSS | 243 | CMGWLPWWRTHC |

| 218 | CGDRLCRMLWLC | 244 | CPWLIRGLVGCC |

| 221 | DRCWSILATSTF | 248 | CGIRWLAFPYGC |

| 223 | HLLWVCPGGAPC | 253 | VLGMARWVDLGS |

| 225 | CGRVGMDVMGGC | 258 | SVVSSVWRVSDS |

Amino acids are represented by their single-letter codes.

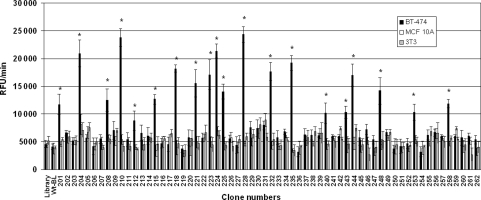

Cell-internalization studies with anti-6xhis tag antibody and β-lactamase substrate

Figure 4 presents the results of cell internalization of selected β-lactamase-peptide fusions. All the fusion proteins that were found to specifically bind BT-474 were studied for their cell internalization using an anti-6xHis tag antibody-Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate and confocal microscopy. The photomicrographs presented in Fig. 4A show positive green fluorescence signals against hexahistidine tag in the BT-474 breast cancer cells treated with the purified β-lactamase-peptide proteins from clones 201, 218, 221, 225, 228, 232 and 235. The analysis of Z-series optical sections from a confocal laser scanning microscope clearly showed the presence of green fluorescence in the cytoplasm. These peptide fusion proteins in the non-cancer breast epithelial MCF 10A cells, which were used as negative cell control, did not produce the positive signals. The negative fusion protein controls, comprised a pool of fusion proteins from the unselected library clones or the β-lactamase protein without a fusion peptide, also exhibited negative results for the 6xHis tag staining. The photomicrographs representing negative results for cell internalization show only blue DAPI nuclear staining. The experiments were also conducted to show that the cell internalization of the selected β-lactamase proteins is mediated by their fusion peptides. The results showed that the incubation of BT-474 cells with two synthetic peptides 228 (VWGVFGGCSQRP) and 235 (CGLGWCGVRWGC), from linear and cyclic categories, strongly inhibited the cell internalization of their corresponding β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins. However, the incubation with random control peptides did not affect the cell internalization of these fusion proteins (images not presented).

Fig. 4.

Microscopic imaging of the human breast cancer cells for internalization of β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins. (A) The figure shows the results of fluorescence imaging of the internalized fusions using anti-6xHis antibody-AlexaFluor 488 conjugate as a probe. The β-lactamase-peptide proteins from clones 201 (a), 218 (b), 221 (c), 225 (d), 228 (e), 232 (f) and 235 (g) showed the fluorescence staining only in BT-474 cells (first row) not in MCF 10A cells (third row). The negative clone control (h), which comprised a pool of β-lactamase fusion proteins from the unselected library clones did not show any staining in either BT-474 cells or MCF 10A cells. The images in the second and fourth rows are corresponding DAPI nuclear staining in BT-474 and MCF 10A cells, respectively. The magnified confocal images of some of the positively stained cells for 6xHis are presented in the fifth row. The figures i (clone 228), j (clone 232) and k (clone 235) represent cytoplasmic staining of internalized β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins. (B) The cell internalization of β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins was also visualized by the enzymatic cleavage of β-lactamase substrate CCF4 loaded within the cells. The results of this study are represented by the fusion proteins from clones 232 (l,m) and 235 (n,o) showing positive blue fluorescence in BT-474 cells (l,n) and negative green in MCF 10A cells (m,o). The cells exposed to a pool of fusion proteins from unselected library (negative clone control) exhibit green fluorescence in both BT-474 cells (p) and MCF 10A cells (q), indicating no internalization. The size bars measure 20 µm in length.

The results of cell internalization of different β-lactamase-peptide conjugates were confirmed by another method that uses β-lactamase enzyme detection in which the cell-loaded substrate that emits a green fluorescence is converted to a blue fluorescence enzyme product. The results of these studies are represented by the images (Fig. 4B) for β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins from clones 232 and 235. The positive blue fluorescence signals for the intracellular presence of β-lactamase were clearly visible in the BT-474 cancer cells, while the same enzyme-peptide fusion protein showed negative green fluorescence signals in the MCF 10A non-cancer breast epithelial cells. The fusion proteins from a pool of unselected library clones, which were used as a negative fusion-peptide control, showed green fluorescence signals in both the BT-474 and MCF 10A cells, indicating no internalization.

Binding and cell-internalization studies in different cancer and non-cancer cell lines

The fusion peptides which were found to internalize BT-474 cells were screened for their binding and internalization to 11 other cancer and non-cancer cell lines. The cell binding of a fusion peptide to cell lines was graded based on its fluorescent enzyme product staining in BT-474 cells. None of the seven fusion peptides tested showed any significant cell binding or internalization in non-cancer human breast epithelial MCF 10A and MCF 12A cells, non-cancer human breast fibroblast HS 578Bst cells and mouse fibroblast 3T3 cells (Table II). The β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein 201 was found to variably bind to MDA-MB-468, SUM159, MCF-7 and T-47D human breast cancer cells with a detectable cell internalization in only MDA-MB-468. The fusion peptide 218 showed some binding to MDA-MB-361, SUM159 and HS 578T human breast cancer cells with cell internalization in MDA-MB-361. No internalization of fusion peptide 221 was observed in any other tested cancer cell lines, though it showed positive binding to SUM159, MDA-MB-468, SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-361 cancer cells. The fusion peptide 225 showed binding to MDA-MB-361 and T-D47 cancer cells without any detectable internalization. The fusion peptide 228 internalized in SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-361 cancer cells and showed a variable degree of binding to MDA-MB-361, T-D47, SK-BR-3, SUM159 and MDA-MB-468. The fusion peptide protein 232 showed a binding to T-47D, SK-BR-3, SUM159, MDA-MB-361 and HS 578T cancer cells with a detectable internalization in T-47D only. No cell internalization of fusion peptide 235 was observed in any of the cancer cell lines tested, though it showed some binding to SK-BR-3, MDA-MB-361 and HS 578T cells.

Table II.

The binding and cell internalization of β-lactamase fusion peptides, which were found to internalize into breast cancer BT-474 cells, to certain other human breast cancer and non-cancer cell lines

| Cell lines/fusion peptide number | 201 | 218 | 221 | 225 | 228 | 232 | 235 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer cells | |||||||

| BT-474 | +++ (Y) | +++ (Y) | +++ (Y) | +++ (Y) | +++ (Y) | +++ (Y) | +++ (Y) |

| T-47D | + (N) | − (N) | − (N) | + (N) | ++ (N) | ++ (Y) | − (N) |

| MDA-MB-468 | +++ (Y) | − (N) | + (N) | − (N) | + (N) | + (N) | − (N) |

| SK-BR-3 | − (N) | − (N) | + (N) | − (N) | ++ (Y) | ++ (N) | + (N) |

| MCF-7 | + (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) |

| MDA-MB-361 | − (N) | ++ (Y) | + (N) | ++ (N) | +++ (Y) | + (N) | + (N) |

| SUM159 | ++ (N) | + (N) | ++ (N) | − (N) | ++ (N) | ++ (N) | − (N) |

| HS 578T | − (N) | + (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | + (N) | + (N) |

| Non-cancer cells | |||||||

| MCF 10A | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) |

| HS 578Bst | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) |

| MCF 12A | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) |

| 3T3a | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) | − (N) |

The cell lines that showed binding to a β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein similar to that of BT-474 cells were graded as +++. The cell lines that showed lesser binding than BT-474 cells were graded as ++ or +, depending on the magnitude. The cell lines that did not show significant binding to a β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein are presented with a minus sign (−). The β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins were also tested for their cell internalization; the results are presented as yes (Y) and no (N). The results represent the average of three experiments. aMouse fibroblast cell line was used as an unrelated non-cancer cell control.

Consensus sequence motifs shared by selected fusion peptides

The β-lactamase fusion peptides from the cancer cell-binding clones were aligned to determine if they share any consensus sequence motif. Table III presents some of the motifs these dodecapeptides share. The motifs CG[V/I/L]XW, [M/V/I]XGL, [V/M]X[W/F][V/L], [M/L/V]XWXC are shared by three fusion peptides. The consensus sequences [V/I]RGL[L/V]GC, [R/K][W/F]LA[F/Y]P, CG[V/I/L]RW and [M/L]LW[L/V]C are examples of other significant motifs shared by cell-binding β-lactamase fusion peptides. Some of the cell-internalizing fusion peptides also share LSVX[M/V]XGL (201/212 and 232), VXGGC (225 and 228), GLXXCG (201/212 and 235) and GXXXC[M/V]XWXC (218 and 235) motifs. It is interesting to note that the motif CG[V/L]XW is present at two places in the cell-internalizing sequence CGLGWCGVRWGC (clone 235).

Table III.

Consensus sequence motifs shared by the human breast cancer BT-474 cell-binding β-lactamase fusion peptides

|

Amino acids sharing consensus motifs are written in bold and highlighted; white letters, exactly the same; black letters, conservative substitution. Amino acid sequences are represented by their single-letter codes. *Cell-internalizing clones.

Discussion

The development of targeted cancer therapeutics requires generation of ligands that specifically bind to the targets, which are either cancer specific or sufficiently overexpressed in cancer cells to provide targeting specificity. Phage display libraries are now established as a single pot resource for rapid generation of affinity ligands to a wide range of self- and non-self antigens, including those related to the cancer growth and metastasis. Phage libraries have been constructed in various formats for general and specific usage with continuous improvements in their features so as to make the selection process more specific and efficient (Paschke, 2006; Brissette and Goldstein, 2007). In the present study, we used a new kind of phage display library in which the random linear or cysteine-constrained peptides were expressed as amino-terminus fusion to β-lactamase enzyme. We employed pIII signal peptide of Sec-pathway for periplasmic translocation of β-lactamase fusion protein as it was found to be more efficient than DsbA signal peptide of SRP pathway (Shukla and Krag, 2009). The sequence analysis of the clones from both libraries showed that two-step cloning was helpful in avoiding insert-less clones. The expression yields, specific activity and stability of β-lactamase were not affected by the fusion of peptides.

Several cancer cell-binding and internalizing β-lactamase-peptide fusion ligands were isolated by selecting these libraries on the live BT-474 human breast cancer cells. All the positive β-lactamase-peptide fusions gave no signal above the background on MCF 10A cells in cell-binding studies, indicating that the negative subtractions at each round of selection effectively depleted the clones that bind to common breast epithelial targets. Three rounds of the biopanning produced a significant enrichment in the cell-internalized clones. We used chloroquine in the first round of biopanning. It is well documented that chloroquine accumulates within lysosomes, increases internal pH and thereby inhibits lysosomal hydrolases and prevents degradation of macromolecules including filamentous phages (Poole and Ohkuma, 1981; Becerril et al., 1999; Ivanenkov et al., 1999). This step should have helped to preserve the diversity of internalized clones in the first round of biopanning when their copy numbers were very low. In the subsequent rounds, when the copy numbers of input clones were exponentially higher, the chloroquine treatment was omitted. This strategy should have helped to select even those clones that might have otherwise been lost in the first round of panning if done without chloroquine. Furthermore, the trypsin treatment of cells following the low pH elution step also helped to remove the left-over surface-bound phage by digesting the protease cleavable linker between phage pIII and β-lactamase-peptide fusion protein. In our standardization experiments, we consistently observed 11–18% higher elution of surface-bound phage from trypsin-treated cells in comparison to an identical set of cells that were treated with PBS. These two steps should have contributed towards the observed significant enrichment in the cell-internalized intact phages. The identified ligands share several significant motifs, which show their selectivity and possible binding to some common cancer cell targets. Of particular interest are LSVX[M/V]XGL, VXGGC, GLXXCG, GXXXC[M/V]XWXC and CG[V/L]XW motifs that are shared by the cell-internalizing peptide fusions. The competition studies with free peptides have clearly shown that the peptide part of the β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins is responsible for the cell binding and internalization of the tested fusions. The specificity of the selected ligands was also studied for their binding and internalization in 11 other cancer and non-cancer cell lines. It was observed that the BT-474-internalizing fusion proteins also bind and/or internalize to several other human breast cancer cell lines. However, none of these ligands showed significant binding or internalization to the non-cancer human breast epithelial cells, non-cancer human breast fibroblast cells and an unrelated mouse fibroblast cells. These studies demonstrate the selective specificity of these fusion proteins towards certain breast cancer cells.

The cell-internalized clones, in the present study, were expressed in a suppresser host for producing free peptide-β-lactamase fusion proteins used in cell-binding and internalizing studies. The ligands selected from our libraries do not require peptide synthesis and modifications (e.g. biotinylated, fluorescently tagged, enzyme linked), and can be used directly for any application that requires tracking. Peptide-β-lactamase fusion ligands can be readily produced in bulk and being a stable single-domain protein it is easy to purify (Cartwright and Waley, 1984). The presence of β-lactamase fusion made the whole process of clone screening simple. The concentrations of β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins in phage samples, lysates and purified fusion protein preparations can be normalized based on the β-lactamase activity. The screening of clone binding was also based on assaying the residual cell-bound β-lactamase activity. β-Lactamase is a high turnover enzyme with several available chromogenic and fluorogenic substrates (O'Callaghan et al., 1972; Jones et al., 1982; Gao et al., 2003; Xing et al., 2005) that can be suitably adopted for conducting fast and sensitive screening. β-Lactamase activity assay procedure used in the present study is a one-step process that requires only 10 min. β-Lactamase enzyme-based protocol offers several advantages over standard phage display protocols. Unlike phage-ELISA, it does not require antibodies, secondary proteins and multiple time-consuming steps of lengthy incubations and washings (Pero et al., 2004; Shukla and Krag, 2005c). Seven of the 18 unique cancer cell-binding β-lactamase-peptide fusion proteins showed cell internalization by both immunofluorescence and β-lactamase activity-based procedures. The staining with FRET-based substrate CCF4 confirmed the functional integrity of the internalized β-lactamase, and demonstrated that at least a part of the internalized enzyme conjugate could escape the endosomal degradation pathway in the intact form and reacted with the substrate present in the cytoplasm. However, a series of experiments examining the colocalization of a candidate fusion peptide with endosome and lysosome markers at different time intervals will be required for determining the sequential metabolic fate and life expectancy of the conjugate in the cells. The esterified derivatives of CCF2 and CCF4 are very sensitive substrates and have been reported to localize individual cells containing fewer than 100 β-lactamase molecules (Zlokarnik et al., 1998). However, the use of these substrates in internalization studies limits the choice of membrane stripping buffers as some of the commonly employed chemicals were found to interfere with the dye loading in the cells. Furthermore, all the assay steps require working with live cells that makes it a continuous assay without a choice to stop in the middle. On the contrary, the assay with immunofluorescence localization of the His-tag can be stopped following the fixation of cells and further steps can be carried out next day. The disadvantage of the His-tag assay is that it does not provide any information about the functional integrity of the fusion enzyme. It was surprising to find that several clones, selected from our biopanning protocol that was designed for isolating cell-internalized clones, specifically bound to cancer cells but did not show cell internalization. The cell surface densities of these clone-binding receptors may be very low, resulting into very few internalized clones that remained undetected by our microscopic techniques. The other reason could be that the cell internalization of these clones may be more favorable as the phage-displayed proteins than the free proteins used in our screening protocol. Furthermore, the phage display of more than one copy of β-lactamase fusion peptides could also be facilitating their internalization. It has been reported that phage displaying multiple copies of scFv or homodimeric diabodies are more efficiently endocytosed than monomeric scFv (Becerril et al., 1999). It appears that the use of cell-binding assay as a primary screening tool in our investigation may be responsible for detecting these non-internalizing cell binders. In most of the published cell internalization studies, the clones selected from biopanning protocols were directly screened for their cell internalization, thus leaving behind such non-internalizing cell binders undetected (Poole and Ohkuma, 1981; Becerril et al., 1999; Ivanenkov et al., 1999).

β-Lactamase has been reported to show versatility and very high activity towards cephalosporins and their prodrug conjugates, some of which have been used in preclinical antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT) studies (Meyer et al., 1993; Vrudhula et al., 1993; Kerr et al., 1995; Svensson et al., 1995; Vrudhula et al., 1995). Since targeted prodrug therapy requires only target-specific presence of the enzyme, both cancer cell-internalizing as well as binding β-lactamase-peptide ligands can be used directly for targeted enzyme prodrug therapy. β-Lactamase has shown high in vivo stability in preclinical ADEPT studies (Meyer et al., 1993; Svensson et al., 1995; Siemers et al., 1997). Furthermore, the identification of P99 β-lactamase-specific CD4+ T-cell epitopes and their removal in the variants has been reported to have lower immunogenicity in mice (Harding et al., 2005). Cephalosporin prodrugs of mechanistically diverse anticancer agents such as doxorubicin (Svensson et al., 1995), taxol (Vrudhula et al., 2003), platinum complexes (Hanessian and Wang, 1993), phenylenediamine mustard (Kerr et al., 1995) and vinblastine (Meyer et al., 1993) have been successfully used with β-lactamase in experimental studies. The cell-internalizing ligands from our libraries can also be used for the targeted delivery of other therapeutic agents, such as genes, toxins, radionuclides, etc., to cancer cells; however, it will require establishing first that the selected peptides in conjugation with a desired therapeutic molecule internalize the cells.

In conclusion, our studies have shown that the phage display libraries of random peptides constructed in conjugation with functional β-lactamase can be efficiently selected for cancer cell-internalizing ligands. The β-lactamase fusion to peptides not only accelerates the clone screening process but can also facilitate the tracking of ligand molecules in various biological studies. The cancer-specific affinity reagents selected from these libraries have a potential for their use in targeted therapies. This is the first report on the selection of cell-internalized enzyme conjugates using phage display technology, which opens the possibility of creating and selecting new fusion libraries of other relevant enzymes in future.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health [RO1CA112091] and the SD Ireland Cancer Research Fund.

Footnotes

Edited by Hugues Bedouelles

References

- Allen T.M. Nat. Rev. 2002;2:750–763. doi: 10.1038/nrc903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagshawe K.D. Curr. Drug Targets. 2009;10:152–157. doi: 10.2174/138945009787354520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerril B., Poul M.A., Marks J.D. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;255:386–393. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begent R.H., et al. Nat. Med. 1996;2:979–984. doi: 10.1038/nm0996-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette R., Goldstein N.I. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;383:203–213. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-335-6_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette R., Prendergast J.K., Goldstein N.I. Curr. Opin. Drug Dis. Dev. 2006;9:363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright S.J., Waley S.G. Biochem. J. 1984;221:505–512. doi: 10.1042/bj2210505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown J., Pegram M. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2003;79(Suppl. 1):S11–S18. doi: 10.1023/a:1024373306493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwirla S.E., Peters E.A., Barrett R.W., Dower W.J. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:6378–6382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S.A., Wang X., Noronha E.J., Kageshita T., Ferrone S. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2417–2425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duez C., Frere J.M., Ghuysen J.M., Van Beeumen J., Delcambe L., Dierickx L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1982;700:24–32. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(82)90287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs H., Bachran C. Curr. Drug Targets. 2009;10:89–93. doi: 10.2174/138945009787354557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Xing B., Tsien R.Y., Rao J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11146–11147. doi: 10.1021/ja036126o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanessian S., Wang J. Can. J. Chem. 1993;71:896–906. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi N., Kipriyanov S., Fuchs P., Welschof M., Dorsam H., Little M. Gene. 1995;160:129–130. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00218-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenkov V.V., Felici F., Menon A.G. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1448:463–472. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.N., Wilson H.W., Novick W.J., Jr, Barry A.L., Thornsberry C. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1982;15:954–958. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.5.954-958.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D.E., Schreiber G.J., Vrudhula V.M., Svensson H.P., Hellstrom I., Hellstrom K.E., Senter P.D. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3558–3563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsner K.M. AANA J. 2003;71:55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krag D.N., Shukla G.S., Shen G.P., Pero S., Ashikaga T., Fuller S., Weaver D.L., Burdette-Radoux S., Thomas C. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7724–7733. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen P., Winter G. Fold. Des. 1998;3:321–328. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandava S., Makowski L., Devarapalli S., Uzubell J., Rodi D.J. Proteomics. 2004;4:1439–1460. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D.L., Jungheim L.N., Law K.L., Mikolajczyk S.D., Shepherd T.A., Mackensen D.G., Briggs S.L., Starling J.J. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3956–3963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri D., Bicknell R. Nat. Rev. 2005;5:436–446. doi: 10.1038/nrc1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan C.H., Morris A., Kirby S.M., Shingler A.H. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1972;1:283–288. doi: 10.1128/aac.1.4.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschke M. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;70:2–11. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegram M.D., Pietras R., Bajamonde A., Klein P., Fyfe G. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:1776–1781. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pero S.C., Shukla G.S., Armstrong A.L., Peterson D., Fuller S.P., Godin K., Kingsley-Richards S.L., Weaver D.L., Bond J., Krag D.N. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;111:951–960. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole B., Ohkuma S. J. Cell Biol. 1981;90:665–669. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigoutsos I., Floratos A. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:55–67. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodi D.J., Soares A.S., Makowski L. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;322:1039–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00844-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla G.S., Krag D.N. Oncol. Rep. 2005a;13:757–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla G.S., Krag D.N. J. Drug Target. 2005b;13:7–18. doi: 10.1080/10611860400020464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla G.S., Krag D.N. J. Immunoassay Immunochem. 2005c;26:89–95. doi: 10.1081/ias-200051990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla G.S., Krag D.N. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2006;6:39–54. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla G.S., Krag D.N. J. Mol. Recognit. 2009;22:425–436. doi: 10.1002/jmr.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla G.S., Krag D.N. J. Drug Target. 2010;18:115–124. doi: 10.3109/10611860903244181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla G.S., Murray C.J., Estabrook M., Shen G.P., Schellenberger V., Krag D.N. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120:2233–2242. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemers N.O., Kerr D.E., Yarnold S., Stebbins M.R., Vrudhula V.M., Hellstrom I., Hellstrom K.E., Senter P.D. Bioconjug. Chem. 1997;8:510–519. doi: 10.1021/bc9700751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.P., Petrenko V.A. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:391–410. doi: 10.1021/cr960065d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson H.P., Vrudhula V.M., Emswiler J.E., MacMaster J.F., Cosand W.L., Senter P.D., Wallace P.M. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2357–2365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szardenings M., Tornroth S., Mutulis F., Muceniece R., Keinanen K., Kuusinen A., Wikberg J.E. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27943–27948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrudhula V.M., Svensson H.P., Kennedy K.A., Senter P.D., Wallace P.M. Bioconjug. Chem. 1993;4:334–340. doi: 10.1021/bc00023a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrudhula V.M., Svensson H.P., Senter P.D. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:1380–1385. doi: 10.1021/jm00008a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrudhula V.M., Kerr D.E., Siemers N.O., Dubowchik G.M., Senter P.D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:539–542. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing B., Khanamiryan A., Rao J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4158–4159. doi: 10.1021/ja042829+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R.C. Cancer. 1990;65:815–822. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900201)65:3+<815::aid-cncr2820651329>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokarnik G., Negulescu P.A., Knapp T.E., Mere L., Burres N., Feng L., Whitney M., Roemer K., Tsien R.Y. Science. 1998;279:84–88. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]