Abstract

Background

Associations between depression, and possibly anxiety, with cardiovascular disease have been established in the general population and among heart patients. This study examined whether cardiovascular disease was more prevalent among a large cohort of depressed and/or anxious persons. In addition, the role of specific clinical characteristics of depressive and anxiety disorders in the association with cardiovascular disease was explored.

Methods

Baseline data from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety were used, including persons with a current (i.e. past year) or remitted DSM-IV depressive or anxiety disorder (N=2315) and healthy controls (N=492). Additional clinical characteristics (subtype, duration, severity, psychoactive medication) were assessed. Cardiovascular disease (stroke and coronary heart disease) was assessed using algorithms based on self-report and medication use.

Results

Persons with current anxiety disorders showed an about three-fold increased prevalence of coronary heart disease (OR anxiety only=2.70, 95%CI=1.31–5.56; OR comorbid anxiety/depression=3.54, 95%CI=1.79–6.98). No associations were found for persons with depressive disorders only or remitted disorders, nor for stroke. Severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms - but no other clinical characteristics - most strongly indicated increased prevalence of coronary heart disease.

Limitations

Cross-sectional design.

Conclusions

Within this large psychopathology-based cohort study, prevalence of coronary heart disease was especially increased among persons with anxiety disorders. Increased prevalence of coronary heart disease among depressed persons was largely owing to comorbid anxiety. Anxiety - alone as well as comorbid to depressive disorders - as risk indicator of coronary heart disease deserves more attention in both research and clinical practice.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, cardiovascular diseases

INTRODUCTION

In 1993 Frasure-Smith et al. showed that after a myocardial infarction, depressed persons were four-to-five times as likely to die within the next six months than their non-depressed counterparts. Although this initial observation turned out to overestimate the true relationship between depression and heart disease (e.g. Nicholson et al., 2006), since then, many studies have examined their association. Both depression and heart disease are leading disorders when considering disease burden. The World Health Organization projected depression and heart disease to become number 1 and 2, respectively, on the list of diseases with the greatest loss of ‘disability adjusted life years’ in 2030 in high-income countries and number 2 and 3 worldwide (Mathers and Loncar, 2006). This suggests an enormous possible gain in public health and disease burden when depression, heart disease and especially their comorbidity could be prevented through increasing knowledge on the link between these two disabling diseases.

Research thus far has mainly focused on two kinds of populations: heart disease patients and the general population. Meta-analyses have shown that among heart patients depression is associated with an 1.8 to 2.6 increased risk of a subsequent cardiovascular event or death (Barth et al., 2004;Nicholson et al., 2006;van Melle et al., 2004), while in the general population depression increases risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) about 1.6 to 1.8 times (Nicholson et al., 2006;Rugulies, 2002;Van der Kooy et al., 2007;Wulsin and Singal, 2003). Although, as suggested by Nicholson et al. (2006), these estimates may still be inflated due to incomplete and biased reporting of adjustment for conventional risk factors and CVD severity. Studies on prevalence of CVD within a psychopathology-based population are largely lacking. From a psychiatrist perspective, it would be of great importance to know whether clinically depressed patients indeed have a higher prevalence of CVD and how much increased exactly this prevalence is. What’s more, it has hardly been addressed whether specific characteristics of depression, such as age of onset, duration, or severity of the disorder could further determine the exact CVD probability, or whether the association is restricted to specific subtypes, such as atypical or melancholic depression. This knowledge could give insight into underlying mechanisms that relate depression and CVD as well as into which patients should be most closely monitored for cardiovascular dysfunctioning.

Besides depression, some studies have suggested anxiety to be associated with CVD as well (Albert et al., 2005;Fan et al., 2008;Kawachi et al., 1994). Anxiety disorders lead to comparable levels of disability as depression and heart disease (Buist-Bouwman et al., 2006) and have been found to increase risk of premature all-cause and cardiovascular death (Denollet et al., 2009;Phillips et al., 2009). The association between anxiety and CVD, however, has been far less studied than the link between depression and heart disease. Even less studied has been the association between anxiety characteristics (subtype, duration, severity) and CVD. Furthermore, as depression and anxiety are often found to be co-morbid, it would be of great importance to study the association between depression and anxiety with CVD in concert. This could shed light on the specificity of associations between depressive and anxiety disorders and CVD.

Therefore, in the present study within a large cohort of depressed and/or anxious persons and healthy controls we examined the (extent of the) association between the presence of a psychiatric diagnosis of depressive and/or anxiety disorder with CVD. In addition, we assessed the specificity of these associations by directly comparing depressive with anxiety disorders and by examining whether specific characteristics of depressive and/or anxiety disorders (subtype, duration, severity, psychoactive medication) could be identified that indicate increased probability of CVD.

METHODS

Sample

The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) is an ongoing cohort study designed to investigate the long-term course and consequences of depressive and anxiety disorders. Participants were 18 to 65 years old at baseline assessment in 2004–2007 and were recruited from the community (19%), general practice (54%) and secondary mental health care (27%). A total of 2981 persons were included, consisting of persons with a current or past depressive and/or anxiety disorder (N=2329) and healthy controls (N=652). A detailed description of the NESDA study design and sampling procedures can be found elsewhere (Penninx et al., 2008). The research protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of participating universities and after complete description of the study all respondents provided written informed consent.

As subclinical symptoms of on the one hand depressive and anxiety disorders and on the other hand CVD could to a certain degree resemble each other (e.g. feeling tired or pain on the chest) and could therefore falsely indicate or elevate an association between them, persons with subthreshold symptoms of depression or anxiety but no formal diagnosis of depressive or anxiety disorder (N=158) and persons who self-reported CVD without reporting accompanying appropriate medication use (N=16) were excluded (see below for more details), leaving 2807 persons for the present analyses.

Psychopathology & clinical characteristics

Presence of depressive disorder (major depressive disorder and dysthymia) and anxiety disorder (social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and agoraphobia) was established using the Composite Interview Diagnostic Instrument (CIDI) according to DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2001). The CIDI is a highly reliable and valid instrument for assessing depressive and anxiety disorders (Wittchen, 1994) and was administered by specially trained research staff. Based on CIDI, participants were categorized as having no, current (i.e. in past year), or a remitted (lifetime, but not current) depressive and/or anxiety disorder. In addition, a categorical variable was constructed classifying persons as having no depressive or anxiety disorder, remitted depressive or anxiety disorder, current depressive disorder only, current anxiety disorder only, or current depressive and anxiety disorder.

Clinical characteristics examined included the subtype, duration and severity of the depressive or anxiety disorder. Next to CIDI diagnoses, subtypes of depressive disorder included first onset versus recurrent major depressive disorder (based on CIDI interview), presence of an atypical symptom profile, and presence of a melancholic symptom profile. Atypical symptom profile (mood reactivity and ≥ 2 of hyperphagia, hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and interpersonal rejection sensitivity) was constructed by comparison of items of the 28-item self-report Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (IDS (Rush et al., 1996)) with DSM-IV criteria for atypical depression following Novick’s algorithm (Novick et al., 2005). Similarly, melancholic symptom profile (lack of mood reactivity or loss of pleasure and ≥ 3 of distinct mood quality, mood worse in morning, early morning awakening, psychomotor retardation or agitation, anorexia/weight loss, and guilt feelings) was constructed based on comparison of IDS items with DSM-IV criteria using the algorithm proposed by Khan (Khan et al., 2006). Additionally, for both depressive and anxiety disorders a distinction was made between late onset (≥ 30 years old) and early onset (< 30 years old) of the psychiatric disorder, as derived from the CIDI interview. Using the Life Chart method (Lyketsos et al., 1994), a detailed account of the presence of depressive and anxiety symptoms during the past four to five years was assessed among persons with depressive or anxiety disorders. From this, the percent of time patients reported depressive or anxiety symptoms was computed as a measure of duration. Severity of depressive symptoms was assessed by means of the IDS; severity of anxiety symptoms by means of the 21-item Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI (Beck et al., 1988)).

To account for possible psychoactive medication effects, medication use was assessed based on drug container inspection of all drugs used in the past month and classified according to the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification (WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, 2007). As effects of psychoactive medication are likely negligible when used infrequently, use of psychoactive medication was only considered present when taken on a regular basis (at least 50% of the time). Antidepressants included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (ATC-code N06AB), tricyclic antidepressants (N06AA) and other antidepressants (N06AF/N06AX). Benzodiazepines included ATC-codes N03AE, N05BA, N05CD and N05CF.

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) included stroke, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and coronary artery bypass grafting and was adjudicated using standardized algorithms considering self-report and medication use (based on drug container inspection and ATC coding). During the interview, participants were asked if they ever had a stroke, a heart condition or a heart attack, and to specify the kind of condition. In addition, it was asked whether subjects were ever troubled by chest pain during physical strain and whether the pain disappeared within 10 minutes after standing still or taking a tablet under the tongue. If subjects responded positively on both questions this was regarded as an indication of angina pectoris (symptoms). Stroke was identified by self-report supported by use of either anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents (antithrombotic agents [ATC-code B01], acetylsalicylic acid [N02BA01; ≥50% use of ≤100 mg], or carbasalate calcium [N02BA15]), any medication for hypertension (antihypertensives [C02], diuretics [C03], beta blocking agents [C07], calcium channel blockers [C08], agents acting on renin-angiotensin system [C09]), or lipid modifying agents (C10). Angina pectoris and myocardial infarction were only considered present when self-report (or symptoms) of the disease was supported by use of medication for coronary heart disease (CHD; beta blocking agents [C07], nitrate vasodilators [C01DA], calcium channel blockers [C08], or anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents [B01, N02BA01 ≥50% use of ≤100 mg, N02BA15]). When self-report was not confirmed by medication use, CVD was considered to be ‘undetermined’ and subjects were excluded from the analyses (N=16). When angina symptoms (N=510) were not supported by medication use, persons were considered as having no CVD (N=413). Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and coronary artery bypass grafting were based on self-report only. CVD was subdivided into stroke and CHD (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, angioplasty or bypass). For sensitivity analyses, as beta blockers are sometimes prescribed for anxiety symptoms, a secondary measure of CHD excluded persons with symptoms of angina pectoris and use of a beta blocker only (N excluded=32).

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, and years of education. As lifestyle characteristics can be associated with both CVD and depression/anxiety, smoking status (never, former, current), alcohol intake (<1, 1–14, >14 drinks per week), physical activity (measured with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (Craig et al., 2003) in MET-minutes [ratio of energy expenditure during activity compared to rest times the number of minutes performing the activity] per week) and body mass index (BMI; weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) were assessed.

Statistical analyses

Sample characteristics were compared across persons with and without CVD using independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square statistics for dichotomous and categorical variables. Logistic regression analyses assessed the association with CVD for depressive and anxiety disorders separately and simultaneously, before and after adjustment for a priori selected covariates (sociodemographic [age, sex, years of education] and lifestyle [smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, BMI]). Next, consistency of associations with regard to CVD were assessed by conducting separate adjusted logistic regression analyses for subtypes of CVD (stroke and CHD) and subtypes of CHD (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and CHD surgery [angioplasty or bypass]).

Specificity of associations with regard to clinical aspects of the depressive or anxiety disorder was assessed in a sub-sample of persons with current depressive and/or anxiety disorders using sociodemographic-adjusted logistic regression analyses. First, the association with CVD of depressive disorder versus anxiety disorder was directly compared. Second, associations between specific depressive disorder or anxiety disorder characteristics (subtype, duration, severity, and psychoactive medication use) and CVD were examined.

RESULTS

Mean age of the present sample was 41.8 (SD=13.0) years, 66.4% were women, 19.4% had a remitted and 63.1% had a current depressive or anxiety disorder, while 5.6% had CVD. Table 1 describes sample characteristics comparing persons with and without CVD. Persons with CVD were older, more often men, less educated, more often former smoker, less often moderate drinker, and had a higher BMI. Also, persons with CVD more often had a current anxiety disorder, but not depressive disorder.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by cardiovascular disease status

|

No CVD N=2651 |

CVD N=156 |

p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 41.1 (12.9) | 54.1 (7.8) | <.001 |

| Women, % | 67.7 | 45.5 | <.001 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 12.2 (3.3) | 11.0 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Lifestyle variables | |||

| Smoking status | .001 | ||

| Never, % | 28.4 | 18.6 | |

| Former, % | 32.3 | 46.2 | |

| Current, % | 39.3 | 35.3 | |

| Alcohol intake | .05 | ||

| < 1 drink a week, % | 32.2 | 37.8 | |

| 1–14 drinks a week, % | 52.1 | 42.3 | |

| > 14 drinks a week, % | 15.7 | 19.9 | |

| Physical activity (in MET-minutes/week), mean (SD) | 3720 (3046) | 3423 (3198) | .24 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 25.4 (5.0) | 28.6 (4.8) | <.001 |

| Depression and Anxiety variables | |||

| Depressive disorder | .14 | ||

| No depressive disorder, % | 30.6 | 23.7 | |

| Remitted depressive disorder, % | 24.4 | 29.5 | |

| Current (in past year) depressive disorder, % | 45.0 | 46.8 | |

| Anxiety disorder | .007 | ||

| No anxiety disorder, % | 37.9 | 26.3 | |

| Remitted anxiety disorder, % | 14.6 | 14.1 | |

| Current (in past year) anxiety disorder, % | 47.5 | 59.6 | |

| Depressive and/or anxiety disorder | .03 | ||

| No depressive or anxiety disorder | 17.8 | 12.2 | |

| Remitted depressive or anxiety disorder | 19.4 | 19.2 | |

| Current depressive disorder only | 15.2 | 9.0 | |

| Current anxiety disorder only | 17.7 | 21.8 | |

| Current depressive and anxiety disorder | 29.8 | 37.8 |

Based on independent t-test for continuous variables and chi-square statistics for dichotomous and categorical variables.

Table 2 describes the results of unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses assessing the association of depressive and anxiety disorders with CVD. Remitted disorders were not statistically significantly associated with CVD, but after adjustment current depressive and current anxiety disorders were (OR=1.59, 95%CI=1.02–2.47; OR=2.18, 95%CI=1.45–3.28, respectively). When the presence or absence of a depressive or anxiety disorder was combined in one categorical variable, odds of CVD were increased for persons with a current anxiety disorder alone (OR=1.96, 95%CI=1.06–3.64) as well as for those with a combined current anxiety and depressive disorder (OR=2.35, 95%CI=1.33–4.20) compared to healthy controls. Increased likelihood of CVD was not observed for persons with a current depressive disorder only (OR=0.93, 95%CI=0.44–1.96).

Table 2.

Association* of depressive and anxiety disorders with cardiovascular disease

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Depressive disorder | |||||||

| No depressive disorder | 847 | REF | REF | ||||

| Remitted depressive disorder | 693 | 1.56 | 1.00–2.43 | .05 | 1.50 | 0.93–2.40 | .10 |

| Current (in past year) depressive disorder | 1267 | 1.34 | 0.89–2.01 | .16 | 1.59 | 1.02–2.47 | .04 |

| Anxiety disorder | |||||||

| No anxiety disorder | 1046 | REF | REF | ||||

| Remitted anxiety disorder | 408 | 1.40 | 0.82–2.38 | .22 | 1.31 | 0.74–2.30 | .35 |

| Current (in past year) anxiety disorder | 1353 | 1.81 | 1.24–2.64 | .002 | 2.18 | 1.45–3.28 | <.001 |

| Depressive and/or anxiety disorder | |||||||

| No depressive or anxiety disorder | 492 | REF | REF | ||||

| Remitted depressive or anxiety disorder | 544 | 1.45 | 0.81–2.62 | .21 | 1.27 | 0.68–2.37 | .45 |

| Current depressive disorder only | 418 | 0.86 | 0.43–1.74 | .68 | 0.93 | 0.44–1.96 | .85 |

| Current anxiety disorder only | 504 | 1.80 | 1.01–3.20 | .05 | 1.96 | 1.06–3.64 | .03 |

| Current depressive and anxiety disorder | 849 | 1.86 | 1.10–3.16 | .02 | 2.35 | 1.33–4.20 | .004 |

Based on logistic regression analyses unadjusted and adjusted for age, sex, years of education, smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity and BMI.

Next, effects of depression/anxiety status were assessed separately for odds of having stroke and odds of having CHD (Table 3). Depressive and anxiety disorders were not associated with stroke. In contrast, persons with a current anxiety disorder were 2.5 to 3.5 times more likely to have CHD (OR anxiety only=2.70, 95%CI=1.31–5.56; OR anxiety and depression=3.54, 95%CI=1.79–6.98). No significant association was found for persons with a depressive disorder only (OR=1.41, 95%CI=0.61–3.23). To gain some insight into the direction of the association between psychopathology and CHD, we repeated the current analysis among persons with an early onset (≤ 30 years) of depressive or anxiety disorder (N excluded=269). Since CHD hardly occurs before the age of 30, an early onset suggests that psychopathology was present before CHD. Within persons with an early onset of depressive or anxiety disorder similar results were found (OR depression only=1.37, 95%CI=0.59–3.20; OR anxiety only=2.37, 95%CI=1.12–5.03; OR anxiety and depression=3.26, 95%CI=1.59–6.68; data not tabulated). An additional analysis excluded persons (N=32) who ‘earned’ their status of CHD only based on angina symptoms and use of a beta blocker - sometime used to relieve anxiety symptoms -, but substantial associations remained (OR anxiety only=2.06, 95%CI=0.96–4.44; OR anxiety and depression=2.89, 95%CI=1.41–5.93; data not tabulated). When examining CHD subtypes (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, CHD surgery) associations for current anxiety disorder (with or without depressive disorder) were found for all (see Table 3). Depressive disorders alone also showed increased odds of especially angina pectoris and myocardial infarction, but these were not statistically significant. Because associations of psychopathology were only found with CHD and not stroke, all following analyses were conducted with CHD as the outcome.

Table 3.

Association* of depressive and anxiety disorders with cardiovascular disease subtypes

| Cardiovascular disease subtypes (N=156) | Coronary heart disease subtypes (N=138) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke (N=36) |

Coronary heart disease (N=133) |

Angina pectoris (N=105) |

Myocardial infarction (N=50) |

CHD surgery (N=48) |

|||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| No depressive or anxiety disorder | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | ||||||||||

| Remitted depressive or anxiety disorder | 0.73 | 0.24–2.19 | .57 | 1.65 | 0.79–3.43 | .18 | 2.17 | 0.88–5.34 | .09 | 2.55 | 0.78–8.40 | .12 | 1.44 | 0.49–4.24 | .50 |

| Current depressive disorder only | 0.53 | 0.13–2.18 | .38 | 1.41 | 0.61–3.23 | .42 | 2.16 | 0.82–5.71 | .12 | 2.58 | 0.70–9.46 | .15 | 1.60 | 0.50–5.10 | .42 |

| Current anxiety disorder only | 1.02 | 0.34–3.11 | .97 | 2.70 | 1.31–5.56 | .007 | 2.87 | 1.16–7.11 | .02 | 3.47 | 1.03–11.66 | .05 | 2.69 | 0.94–7.67 | .06 |

| Current depressive and anxiety disorder | 1.37 | 0.49–3.86 | .55 | 3.54 | 1.79–6.98 | <.001 | 4.96 | 2.14–11.49 | <.001 | 4.75 | 1.46–15.47 | .01 | 2.24 | 0.79–6.37 | .13 |

Based on logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, years of education, smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity and BMI; in all analyses the specific CVD or CHD subtype was compared to persons without any CVD (N=2651).

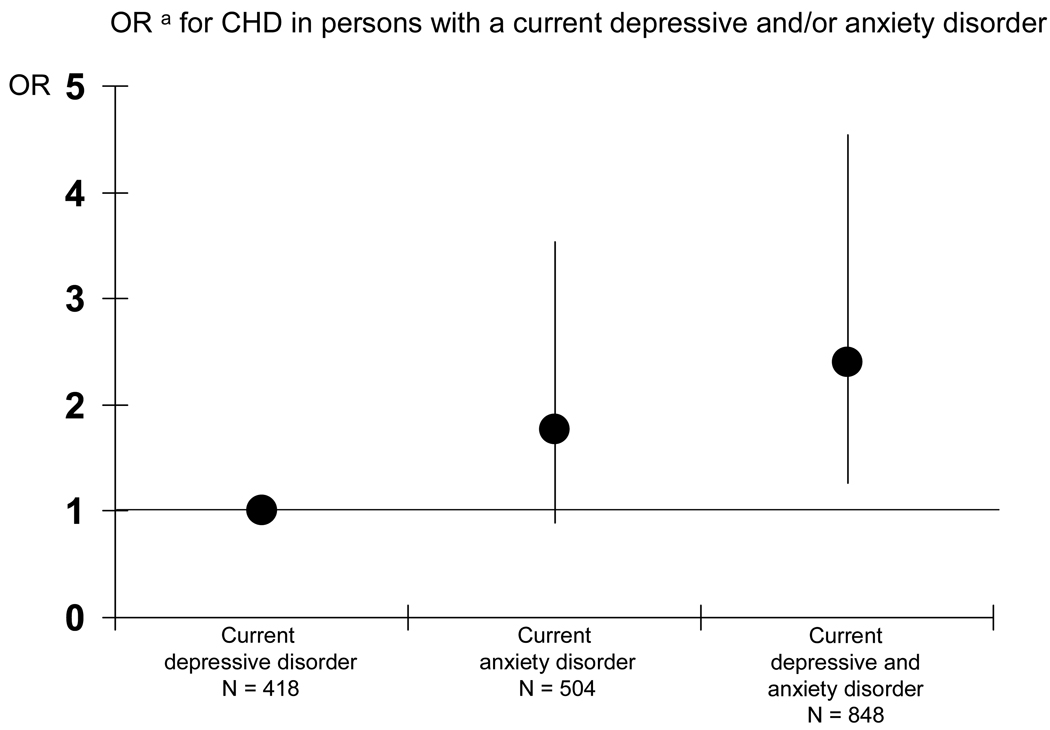

Figure 1 shows that within persons with current psychopathology (N=1770), persons with a current anxiety disorder had almost 80% increased odds to have CHD compared to persons with a current depressive disorder (OR=1.77, 95%CI=0.89–3.54), albeit this was not statistically significant. Odds of CHD for persons having an anxiety disorder in addition to a depressive disorder were more than twofold increased compared to having a depressive disorder alone (OR=2.40, 95%CI=1.27–4.54).

Figure 1.

OR for CHD in persons with a current depressive and/or anxiety disorder.

a based on logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, and education.

Table 4 shows the results of separate sociodemographic-adjusted logistic regression analyses examining associations of depressive and anxiety disorder characteristics with CHD in the sub-sample of persons with current psychopathology (N=1770). No specific subtype of depressive disorder was associated with CHD. For persons with a current anxiety disorder associations with CHD were consistent for persons with generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder and agoraphobia. Duration of depressive or anxious complaints was also not associated with CHD. However, the severity of depressive symptoms (OR per SD increase=1.32, 95%CI=1.05–1.65) and of anxiety symptoms (OR per SD increase=1.36, 95%CI=1.11–1.66) were significantly associated with CHD. In fact, it appeared that the results from Figure 1 showing a somewhat higher OR in persons with comorbid depression and anxiety in comparison to the OR in persons with anxiety disorders alone could be explained by severity of symptoms. After additional adjustment for severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms, odds of CHD for persons with anxiety disorders were equally increased, irrespective of additional depressive disorder (OR anxiety only=1.86, 95%CI=0.91–3.79; OR anxiety and depression=1.95, 95%CI=1.00–3.78). Lastly, psychoactive medication use did not statistically significantly increase odds of CHD, but a trend was found for use of benzodiazepines and higher odds of CHD (OR=1.60, 95%CI=0.95–2.71). Benzodiazepine use did not affect the before presented results (i.e. ORs of CHD as presented in Table 3 and Figure 1 were very similar after additional adjustment for benzodiazepine use).

Table 4.

Association of depressive and anxiety disorder characteristics with coronary heart disease

|

No CHD N=1673 |

CHD N=97 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or mean (SD) |

% or mean (SD) |

OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||||

| Type of depressive disorderb | |||||

| First onset major depressive disorder (vs. recurrent) | 46.4 | 41.8 | 0.95 | 0.56–1.61 | .85 |

| Atypical symptoms | 20.8 | 24.2 | 1.53 | 0.83–2.83 | .17 |

| Melancholic symptoms | 11.9 | 16.7 | 1.08 | 0.53–2.18 | .84 |

| Late onset (≥ 30 years old) | 35.0 | 61.8 | 1.11 | 0.65–1.92 | .70 |

| Type of anxiety disorderc | |||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 44.9 | 50.0 | 1.15 | 0.72–1.82 | .56 |

| Social phobia | 55.5 | 53.6 | 1.08 | 0.68–1.72 | .74 |

| Panic disorder | 55.1 | 53.6 | 1.13 | 0.71–1.80 | .62 |

| Agoraphobia | 16.0 | 25.0 | 1.21 | 0.70–2.10 | .49 |

| Late onset (≥ 30 years old) | 22.6 | 43.4 | 1.06 | 0.65–1.73 | .83 |

| Durationd | |||||

| Percent of time with symptoms in past 4 years | 52.4 (35.6) | 58.8 (35.3) | 1.02 | 0.56–1.86 | .95 |

| Severityd | |||||

| Current depressive symptoms score (IDS) | 28.5 (12.4) | 32.2 (13.0) | 1.32e | 1.05–1.65 | .02 |

| Current anxiety symptoms score (BAI) | 16.5 (10.8) | 20.0 (9.7) | 1.36e | 1.11–1.66 | .003 |

| Psychoactive medicationd | |||||

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use | 25.1 | 21.6 | 0.87 | 0.52–1.45 | .60 |

| Tricyclic antidepressant use | 3.8 | 7.2 | 1.56 | 0.68–3.57 | .30 |

| Other antidepressant use | 8.8 | 12.4 | 1.26 | 0.65–2.41 | .49 |

| Benzodiazepine use | 10.5 | 22.7 | 1.60 | 0.95–2.71 | .08 |

Based on logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, and education; each line represents a single analysis.

Within sub-sample of persons with a current (past year) depressive disorder: N=1266; first onset vs. recurrent: persons with dysthymia only (N=44) were excluded.

Within sub-sample of persons with a current (past year) anxiety disorder: N=1352.

Within sub-sample of persons with a current (past year) depressive and/or anxiety disorder: N=1770.

Per SD increase: IDS: SD=12.9; BAI: SD=10.7.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the association between diagnosed depressive and anxiety disorders and cardiovascular disease within a large cohort of depressed and/or anxious persons and healthy controls. The results show that, individually, both depressive and anxiety disorders are associated with CVD. However, the increased prevalence of CHD among depressive persons appeared to be mainly owing to comorbidity of anxiety disorders. No associations were found with stroke. Severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms - but no other clinical factors - identified those with the highest prevalence of CHD.

Relatively few studies have examined the link between anxiety and CHD and most of these studies assessed anxiety symptoms, but not diagnosis. Although the link between anxiety (symptoms) and CHD has been more consistently found in initially CHD-free populations than among heart patients (Suls and Bunde, 2005), a recent study (Frasure-Smith and Lesperance, 2008) showed that both a generalized anxiety disorder, as well as severity of anxiety symptoms were associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiac events in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Our results demonstrate that within a psychopathology-based population the prevalence of CHD is increased across a wide range of diagnosed anxiety disorders (social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and agoraphobia). In fact, persons who suffered from any anxiety disorder in the past year were about three times as likely to have CHD. Given the widespread prevalence of anxiety disorders, these results suggest that the role of anxiety disorders in CHD is important and has been largely overlooked thus far. These findings also suggests that cardiac symptoms in anxiety persons might really indicate heart disease and underdiagnosing heart disease in anxiety patients might be a problem.

The possible overlap in symptoms between anxiety disorders and heart disease could also pose a problem in examining the association between these two. We tried to handle this issue by only including definite cases of anxiety and by confirmation of medication use appropriate for CVD. Even when further excluding persons with symptoms of chest pain and use of a beta-blocker only - sometimes described to relieve anxiety symptoms - associations of anxiety disorders with CHD remained. Moreover, associations between anxiety disorders and CHD were found across different types of both CHD and anxiety disorders and were not confined to for instance angina pectoris and panic disorder, supporting the conclusion that the strong association observed between anxiety and CHD is real.

Although a depressive disorder diagnosis was associated with CVD, this relationship appeared to be largely explained by comorbid anxiety. Previous research in the general population and among heart patients consistently showed an association between depression and CVD. Importantly, these studies often did not take into account comorbid anxiety, but many depressed persons have a co-morbid anxiety disorder (in our sample 67%). Similar to our study within a psychopathology-based population, Strik et al. (2003) found that anxiety and not depressive symptoms were an independent predictor of cardiac events among heart patients and accounted for the relationship between depressive symptoms and cardiac events. Longitudinal studies should further disentangle the associations between depression, anxiety and CHD.

Considering clinical characteristics, highest prevalences of CHD were found among those with the most severe symptoms of depression and anxiety. This might suggest that more severe symptoms induce an extra increased risk of CHD. Otherwise, as symptom scales of depression and anxiety often include a set of somatic items, it is possible that severity of depression or anxiety partly reflects severity of heart complaints (Sorensen et al., 2005). Otherwise, somatic health factors might be more important in depressive disorders that are associated with CVD. This might also (partly) explain why other studies, mostly conducted within somewhat older populations, which generally have more somatic conditions, do find more support of a relationship between depression and CVD.

Little evidence was found of other clinical characteristics of depressive or anxiety disorders to be specifically related to CHD. Although we had expected longer lasting psychiatric disorders to be associated with higher prevalence of CVD, the results did not corroborate this. This finding somewhat decreases the plausibility of depressive and anxiety disorders directly causing CVD. Also, associations with remitted psychiatric disorders were not statistically significant, perhaps partly due to decreased reliability of diagnosis assessment in the more far away past. On a more positive side, this might suggest that when persons remit from depressive or anxiety disorders, the odds of CHD decreases. Further, antidepressant medication use was not associated with CHD. Tricyclic antidepressants have been well described to have cardiovascular effects (Glassman, 1998), but this might have been counterbalanced in our study by the fact that these medications are therefore contra-indicated in heart patients. Benzodiazepine use was somewhat more prevalent among persons with CHD, but whether they increase risk of CVD or whether this finding is a reflection of poorer health status in persons with CVD, cannot be decided from this study.

Interestingly, our results only show an association with CHD, but not with stroke. Although some studies do relate psychopathology to stroke (Everson et al., 1998), this has been much less examined than CHD. We examined the association between depression, anxiety and stroke in a relatively young population where stroke was not very prevalent and we were not able to distinguish between ischemic or a hemorrhagic stroke. As an association of depression and anxiety with specifically ischemic stroke is expected, hemorrhagic strokes might have diluted the association.

Our study has some important strengths. We made use of a large sample of persons with diagnosed psychopathology to investigate whether true psychiatric diagnoses of both depression and anxiety are indeed associated with a heightened prevalence of CVD. Furthermore, we were able to examine the effects of a large amount of clinical characteristics of depressive and anxiety disorders. Some limitations have to be noted as well. Our results are based on cross-sectional data. This makes it impossible to draw any conclusions about the causality of associations between depressive and anxiety disorders and CHD. However, a strong association between anxiety disorder and CHD existed in persons with an onset of psychopathology before 30 years. Since CHD hardly occurs before the age of 30, an early onset suggests that psychopathology was present before CHD. Additionally, as depression and anxiety are highly comorbid and had an early onset in most persons (only 269 of 2315 had late onset), it is unlikely that the finding that anxiety is more strongly than depression associated with CHD was biased by the cross-sectional design. Another limitation is that the presence of heart disease was not verified by general practice or hospitalization records. However, self-report was confirmed by medication use and previous research has shown good concordance between self-report of heart disease and general practitioners information, with especially little overreporting (Kehoe et al., 1994;Kriegsman et al., 1996). In conclusion, our results show that anxiety disorders are more strongly associated with coronary heart disease than depressive disorders and might partly account for the widely reported association between depression and heart disease. The highest prevalence of CHD is found among those with the most severe psychiatric symptoms, such as those persons with comorbid depression and anxiety. Anxiety as possible risk factor for cardiovascular disease needs to be more elaborately investigated in future research, and deserves more attention in clinical care as well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE

The infrastructure for the NESDA study (www.nesda.nl) is funded through the Geestkracht program of the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (Zon-Mw, grant number 10-000-1002) and is supported by participating universities and mental health care organizations (VU University Medical Center, GGZ inGeest, Arkin, Leiden University Medical Center, GGZ Rivierduinen, University Medical Center Groningen, Lentis, GGZ Friesland, GGZ Drenthe, Institute for Quality of Health Care (IQ Healthcare), Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL) and Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos). Data analyses were supported by grant R01-HL72972-01 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Study sponsors had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONTRIBUTORS

Authors AB and BP were involved in overall study design and funding. Authors NV, AS, and BP designed and wrote the analysis plan for the current paper. Authors NV and AS undertook the statistical analyses. All authors were involved in the interpretation of data. Author NV wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically read the manuscript to improve intellectual content. All authors have approved the final manuscript in its present form.

REFERENCES

- Albert CM, Chae CU, Rexrode KM, Manson JE, Kawachi I. Phobic anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease and sudden cardiac death among women. Circulation. 2005;111:480–487. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153813.64165.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2004;66:802–813. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146332.53619.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin. Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist-Bouwman MA, de GR, Vollebergh WA, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R, Ormel J. Functional disability of mental disorders and comparison with physical disorders: a study among the general population of six European countries. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006;113:492–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denollet J, Maas K, Knottnerus A, Keyzer JJ, Pop VJ. Anxiety predicted premature all-cause and cardiovascular death in a 10-year follow-up of middle-aged women. J Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62:452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson SA, Roberts RE, Goldberg DE, Kaplan GA. Depressive symptoms and increased risk of stroke mortality over a 29-year period. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158:1133–1138. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan AZ, Strine TW, Jiles R, Mokdad AH. Depression and anxiety associated with cardiovascular disease among persons aged 45 years and older in 38 states of the United States, 2006. Prev. Med. 2008;46:445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F. Depression and anxiety as predictors of 2-year cardiac events in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:62–71. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction. Impact on 6-month survival. JAMA. 1993;270:1819–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH. Cardiovascular effects of antidepressant drugs: updated. J Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 15:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Prospective study of phobic anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Circulation. 1994;89:1992–1997. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe R, Wu SY, Leske MC, Chylack LT., Jr Comparing self-reported and physician-reported medical history. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:813–818. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AY, Carrithers J, Preskorn SH, Lear R, Wisniewski SR, John RA, Stegman D, Kelley C, Kreiner K, Nierenberg AA, Fava M. Clinical and demographic factors associated with DSM-IV melancholic depression. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;18:91–98. doi: 10.1080/10401230600614496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients' self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin. Epidemiol. 1996;49:1407–1417. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Nestadt G, Cwi J, Heithoff K, Eaton WW. The life chart interview: A standardized method to describe the course of psychopathology. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1994;4:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS. Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson A, Kuper H, Hemingway H. Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146 538 participants in 54 observational studies. Eur. Heart J. 2006;27:2763–2774. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick JS, Stewart JW, Wisniewski SR, Cook IA, Manev R, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JF, Shores-Wilson K, Balasubramani GK, Biggs MM, Zisook S, Rush AJ. Clinical and demographic features of atypical depression in outpatients with major depressive disorder: preliminary findings from STAR*D. J Clin. Psychiatry. 2005;66:1002–1011. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Nolen WA, Spinhoven P, Cuijpers P, De Jong PJ, van Marwijk HW, Assendelft WJ, Van Der MK, Verhaak P, Wensing M, de GR, Hoogendijk WJ, Ormel J, Van DR. The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008;17:121–140. doi: 10.1002/mpr.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AC, Batty GD, Gale CR, Deary IJ, Osborn D, MacIntyre K, Carroll D. Generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and their comorbidity as predictors of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: the Vietnam experience study. Psychosom. Med. 2009;71:395–403. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819e6706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugulies R. Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease. a review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002;23:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol. Med. 1996;26:477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen C, Brandes A, Hendricks O, Thrane J, Friis-Hasche E, Haghfelt T, Bech P. Psychosocial predictors of depression in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2005;111:116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strik JJ, Denollet J, Lousberg R, Honig A. Comparing symptoms of depression and anxiety as predictors of cardiac events and increased health care consumption after myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;42:1801–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychol. Bull. 2005;131:260–300. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2007;22:613–626. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Melle JP, de JP, Spijkerman TA, Tijssen JG, Ormel J, van Veldhuisen DJ, van den Brink RH, van den Berg MP. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2004;66:814–822. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146294.82810.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007 Ref Type: Report.

- Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO--Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr. Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulsin LR, Singal BM. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosom. Med. 2003;65:201–210. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000058371.50240.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]