Abstract

Membrane fusion is driven by specialized proteins that reduce the free energy penalty for the fusion process. In neurons and secretory cells, soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor-attachment protein (SNAP) receptors (SNAREs) mediate vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane during vesicular content release. Although, SNAREs have been widely accepted as the minimal machinery for membrane fusion, the specific mechanism for SNARE-mediated membrane fusion remains an active area of research. Here, we summarize recent findings based on force measurements acquired in a novel experimental system that uses atomic force microscope (AFM) force spectroscopy to investigate the mechanism(s) of membrane fusion and the role of SNAREs in facilitating membrane hemifusion during SNARE-mediated fusion. In this system, protein-free and SNARE-reconstituted lipid bilayers are formed on opposite (trans) substrates and the forces required to induce membrane hemifusion and fusion or to unbind single v-/t-SNARE complexes are measured. The obtained results provide evidence for a mechanism by which the pulling force generated by interacting trans-SNAREs provides critical proximity between the membranes and destabilizes the bilayers at fusion sites by broadening the hemifusion energy barrier and consequently making the membranes more prone to fusion.

1. Introduction to SNARE-Mediated Vesicle Fusion

Vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane fusion is essential for survival in eukaryotic cells and organisms. Transmitter release, cellular trafficking and compartmentalization, endocytosis and exocytosis, and sexual reproduction are examples of the many physiologic processes that depend directly or indirectly on membrane fusion 1,2). Conversely, certain pathologic conditions may also arise due to excessive release or defects in the fusion process 3,4). Membrane fusion is mediated by a specialized family of proteins, soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein (SNAP) receptors (SNAREs). Since their introduction as the minimal machinery for membrane fusion 5), SNAREs have been extensively used in model membrane systems to investigate the mechanism for SNARE-mediated membrane fusion 6–9). The SNARE hypothesis postulates that the interaction of cognate SNAREs between opposing (trans) membranes drives triggered, as well as, constitutive membrane fusion (Fig. 1) 10–12). The neuronal v-SNARE, vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP 2, also referred to as synaptobrevin 2) and the plasma membrane t-SNAREs, syntaxin 1A and SNAP-25 (synaptosomal-associated protein of 25 kD) are expressed in the presynaptic terminal and mediate vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane during neurotransmitter release. Interaction between cognate v- and t-SNAREs in trans-membranes forms a ternary core complex (Fig. 2) that contributes significantly to the energy required to fuse the membranes 11,13). It is speculated that upon sensing of Ca2+, the vesicle-associated synaptotagmin interacts with phospholipids and the SNAREs to form a fusion pore that releases the vesicular content 14).

Fig. 1.

Vesicle fusion at the neuronal synapse. Molecular components of the neuronal fusion machinery include VAMP 2, SNAP-25, syntaxin, synaptotagmin and complexin. According to the SNARE hypothesis, synaptic vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane and release neurotransmitters upon triggering by action potentials.

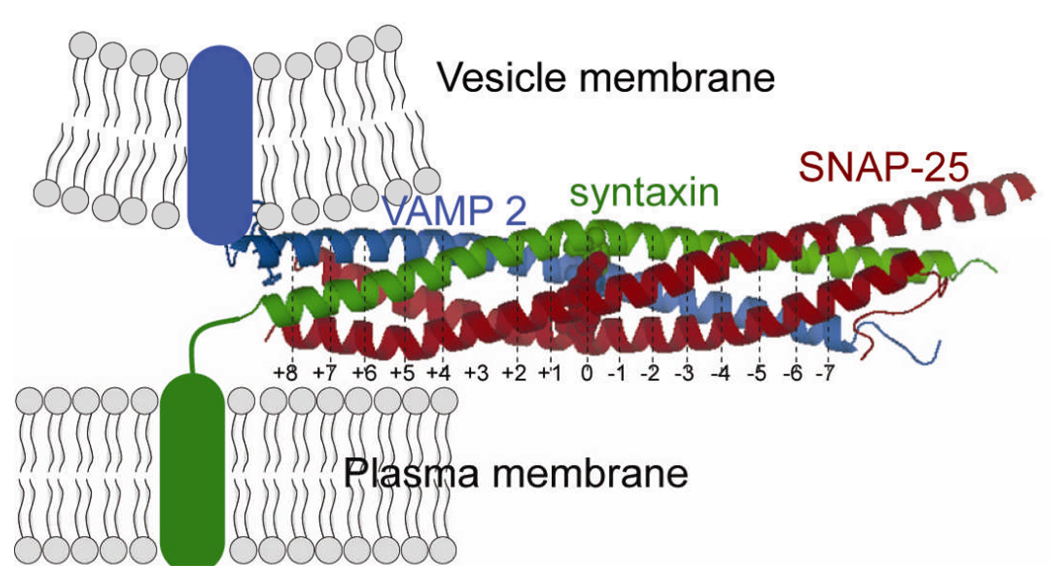

Fig. 2.

Crystal structure of the synaptic ternary SNARE complex. VAMP 2 (blue) anchored in the vesicular membrane binds to the t-SNAREs syntaxin (green) and SNAP-25 (red). Syntaxin is anchored in the plasma membrane via a transmembrane domain, whereas, SNAP-25 is recruited via palmitoylation sites. SNAP-25 binds to syntaxin and VAMP 2 through the conserved sn1 and sn2 domains located in the N- and C-terminals, respectively. The interaction between v- and t-SNAREs forms a ternary core complex that has been described as a parallel α-helical bundle or a coiled coil structure. The SNARE complex is stabilized by 15 hydrophobic layers (+8, +7, …, −6, −7, but not 0)within the α-helical bundle. Residues (VAMP Arg56, syntaxin Gln226, sn1 Gln53, and sn2 Gln74) forming the ionic ‘0’ layer are shown in space-filled spheres.

There are currently two main models for fusion pore formation; the proximity model and the protein-lined fusion pore model 15). The proximity model proposes a mechanical role for the SNARE proteins while zippering, which brings the apposed bilayers into a critical proximity where nucleation of a purely lipidic fusion-pore may take place and membrane fusion can ensue [Fig. 3a]. During this process, the two membranes merge together passing through a hemifused state 16,17). Hemifusion involves the coalescence of the two proximal leaflets (monolayers) followed by that of the remaining distal monolayers of the apposed membranes when full fusion is complete 18). Given the high energy cost for the initiation and opening of the fusion pore 19), the proximity model falls short in explaining the reversible kiss-and-run fusion events observed in vivo 20–24) and, thus, the protein-lined fusion pore model has been invoked 25–27). In this model, a gap junction type of structure for the fusion pore is proposed [Fig. 3b] 28). During formation of the SNARE-complex, the SNAREs pull together and their transmembrane segments begin to oligomerize 29–31) in the apposed membranes to form hemichannel-like structures 25,32). Upon formation of these structures, an open channel (i.e., fusion pore) forms whereby vesicular content is released into the extracellular space 33,34). A fusion pore behaving like an ion channel can account for the fast opening and closing during the reversible kiss-and-run fusion events. Moreover, the protein-lined pore is a transient structure and upon dilation, the transmembrane segments dissociate and lipid molecules are incorporated into the pore as full membrane fusion takes place.

Fig. 3.

Models for SNARE-mediated membrane fusion: (a) the proximity model and (b) the protein pore model.

Numerous studies have focused on the interactions of SNARE proteins with each other or with other proteins to understand their effects on the membranes during fusion 35–40). Other studies have investigated the interactions of SNARE and other protein with the phospholipids of the bilayers 41–43). It has been suggested that the oblique angle of insertion of the transmembrane domain (TMD) of VAMP 2 promotes lipid mixing without forming of the SNARE complex 44). This proposition is consistent with the role of tilted peptides in promoting membrane fusion 45), where the 36° angle of the TMD of VAMP 2, relative to the normal of the lipid bilayer, destabilizes the membrane and may drive fusion. Moreover, most SNAREs are anchored in the membrane at their C-terminal end and the assembly of the SNARE complex has been suggested to occur in the N- to the C-terminal direction 46–48). Consequently, the membranes in which the SNAREs are anchored are pulled together into close proximity, a condition that is more favorable for membrane fusion. However, rather than merely providing apposition between the membranes to promote fusion, our findings based on AFM force measurements along with others’ using bulk fusion assays suggest that the SNARE interaction plays an additional role in destabilizing the lipid bilayers through movement of the SNARE transmembrane segments 49–52).

Despite the numerous studies on membrane fusion, the precise mechanism of SNARE-mediated membrane fusion remains an active area of research. Supported lipid membranes have been extensively used as model systems for biological membranes to understand the mechanisms for the formation of the fusion pore and membrane fusion 53–58). More recently, floating lipid bilayers have emerged as improved models for lipid membranes 59,60). Floating bilayers float ~ 2.5 nm on top supported bilayers 61,62). Since the floating bilayers are further away from the underlying support, the coupling between the substrate and the floating bilayers is reduced, making them more comparable to biological membranes 63). Floating bilayers have been formed mainly by Langmuir-Blodgett deposition followed by a Langmuir-Schaeffer deposition on top of the supported bilayers 64). In the last few years, however, several papers appeared in the literature where double bilayers (i.e., floating on top of supported bilayers) were formed by vesicle adsorption onto hydrophilic substrates 61,65–67). More recently, an experimental system was established where floating lipid bilayers were used to investigate the mechanism for the fusion of SNARE-free and SNARE-containing bilayers 49,68).

2. Experimental System for Induced Bilayer Fusion Using Atomic Force Microscopy

A newly characterized experimental system was established to study membrane fusion. The system provides the necessary resolution to detect induced hemifusion and fusion events between apposed floating lipid bilayers using atomic force microscope (AFM) force spectroscopy 68). The lipid bilayers are formed on a flat glass surface and a glass microbead attached to the cantilever tip [Fig. 4a]. These glass surfaces provide hydrophilic substrates where the floating lipid bilayers are formed by vesicle adsorption. This experimental system also enables force measurements in the piconewton range of the AFM-applied compression required to induce the hemifusion and fusion of the apposed bilayers.

Fig. 4.

AFM measurements of SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. (a) Photograph of AFM and of a microbead attached to the end of an AFM cantilever. (b) AFM compression force measurement (force vs. piezo displacement) of supported double lipid bilayers. At large separation, there is negligible interaction between the bilayers. Upon approach of the AFM cantilever, the bilayers are pressed against one another. With the continued application of force, the bilayers are compressed together until hemifusion takes place and a first jump (J1) is observed at ~ 450 pN (f1). The piezo-electric transducer displacement (d; insert) during the jump is a measure of its distance and reflects the thickness of the fused bilayer. A transient reduction in force takes place as the cantilever tip relaxes during the jump, followed by the continued application of compression, which eventually leads to the appearance of a second jump (J2) at ~ 900 pN (f2), which is indicative of the full fusion of the bilayers. On the other hand, during retraction of the cantilever the force decreases to zero as the cantilever returns to its relaxed position. No adhesion is observed in the presence of protein-free bilayers. The force measurements were performed in Tris buffered saline.

In an AFM force scan measurement, the approach and retraction traces correspond to the movement of the cantilever tip toward and away from the substrate (dish), respectively. As the cantilever is lowered and pressed against the substrate, the bilayers on both surfaces are compressed together and the cantilever is subjected to forces that result in its upward bending. Deflection of the cantilever is monitored by the position of a laser beam reflected off the coated back-side of the cantilever tip onto a two-segment photodiode. Down or upward deflection in the cantilever signifies an attractive or repulsive interaction, respectively. The change of the laser position on the photodiode is calibrated based on the force causing the cantilever deflection and the resulting force scan represents the interaction force versus the displacement of the piezo-electric transducer [Fig. 4b]. It should be noted that the piezo displacement largely results in the deflection (bending) of the AFM cantilever and a negligible compression of the apposed bilayers. However, both components of the applied compression are obtained based on the measured spring constant (κ) of the cantilever. The continued approach of the cantilever leads to further compression of the contacting bilayers, which eventually hemifuse and fully fuse under the compression 68). Hemifusion and fusion are detected during the instability (jump; J1 and J2) in the force scan. The jump is due to the sudden displacement of the cantilever tip toward the substrate as a result of the coalescence of the material in the space between the microbead and the dish. The compression forces required to induce hemifusion (f1) or fusion (f2) of the bilayers are measured from the force scans at the beginning of the jumps J1 and J2, respectively. On the other hand, during retraction the force decreases progressively toward zero as the cantilever returns to its relaxed position.

3. Fusion of Protein-Free Lipid Bilayers

Using the above experimental system, hemifusion and fusion of protein-free lipid bilayers were induced and the compression forces required to induce such events were measured. Different compression rates were achieved by varying the scan velocity during approach of the cantilever toward the substrate to reveal the force versus compression rate curve for the hemifusion process. Egg L-α-phosphatidylcholine (egg PC) or 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) bilayers were formed by vesicle adsorption onto the opposing glass dish and glass microbead attached to the cantilever tip 68). Compression of the apposed bilayers together in the approach step of the force scans revealed jumps that corresponded to the hemifusion and fusion of the bilayers (Fig. 4) 68,69). The compression force measurements were acquired under different bilayer fluidities accomplished by varying the temperature or the lipid compositions. The dynamic force spectrum (DFS) acquired under these conditions revealed that the compression force required to induce hemifusion was significantly reduced when the DMPC bilayers were heated above the melting temperature into the fluid phase as compared to the solid phase [Fig. 5a]. Similar results were obtained when the fluidity of the egg PC bilayers was increased with cholesterol (15 – 25 mol%) [Fig. 5b]. Taken together, these measurements revealed the sensitivity of this novel fusion experimental system to the changes in the bilayer fluidity and supported its validity as an effective tool to investigate the role of SNAREs in mediating membrane fusion.

Fig. 5.

(a) Dynamic force spectra for the hemifusion of DMPC floating bilayers at different temperatures. (b) Dynamic force spectra for the hemifusion of egg PC floating bilayers with different cholesterol concentration. Lines are fits of the dynamic compression model described in the text to the data points. Error bars are the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) all the measured compression forces required to induce hemifusion at the corresponding compression rates.

4. Interpretation and Analysis of the AFM Force Measurements

A dynamic compression model based on the transition state theory was applied to interpret the results obtained from the AFM compression measurements of bilayer hemifusion. In these experiments, it is postulated that the applied compression force f along the reaction coordinate x contributes a mechanical potential fx toward the suppression of the hemifusion activation barrier(s). This is illustrated in Fig. 6a where the height of the energy barrier is decreased as a function of the applied force f. In the dynamic compression model, each of the activation barrier(s) is characterized by the parameters xϕ and k°ϕ, where xϕ describes the width of the energy barrier while is the fusion rate in the absence of applied force and corresponds to the height of the energy barrier 73,74). Experimentally, xϕ and can be derived from fitting the following equation

| (1) |

to the acquired DFS, where f* is the most probable hemifusion force of the membranes at the compression rate rf. As revealed in Fig. 5, the compression force required to induce hemifusion increased linearly with the logarithm of compression rate under the different tested conditions. A single linear regime in the force versus log(compression rate) of the DFS is interpreted as evidence that a single energy barrier dominated the hemifusion process.

Fig. 6.

(a) Schematic illustration of the effect of applied force on the activation potential of the lipid bilayer hemifusion/fusion. The applied force adds a linear term (dotted line) to the thermopotential of the system, which effectively tilts the barrier and reduces the activation potential of the process. (b)Schematic depiction (not to scale) of the energy landscape for the hemifusion of DMPC floating bilayers below and above the melting temperature (Tm) of DMPC. During compression of the apposed individual floating bilayers the bilayers pass (along the gray dashed or dotted lines) through a transition state that is at the peak of an energy barrier. Arbitrary positions along the free energy axis were chosen for the unfused and hemifused bilayers since it is not known which of the states has the lower free energy minimum. On the other hand, we use the initial unfused state, where the compressed individual floating bilayers still exist, as a reference point along the reaction coordinate. Recall that no significant change in the barrier height was observed with temperature for DMPC floating bilayers (see Table 2); in contrast, a pronounced widening (0.61 Å) in the barrier was observed when DMPC bilayers were heated above Tm to 30°C. Broadening of the hemifusion barrier results in reducing its slope and consequently less energy input to overcome it which translates into a facilitation of the fusion process. (c) Kinetic profiles of DMPC membrane hemifusion above (dotted line) and below (solid line) Tm. The increased kinetics of hemifusion for the DMPC membranes is evident in accelerated fusion under compression.

Table 1 summarizes the results obtained from the compression experiments under the different experimental conditions in terms of the hemifusion energy barrier parameters (xϕ and ). The relative difference (δΔG) in the height of the energy barrier between two similar systems can be estimated by 49,68

| (2) |

where the indices 1 and 2 refer, respectively, to the rate of membrane fusion in the compared systems. δΔG values reveal a negligible change (<kBT) in the height of the hemifusion energy barrier in the different experimental conditions [Fig. 6b]. In contrast, a significant increase in the energy barrier width (xϕ) is observed under conditions requiring lower compression forces to induce hemifusion [see Fig. 5 and Fig. 6b]. The increase in the energy barrier width results in a reduction of its slope; a less-steep energy barrier is more sensitive to an applied force and is easier to overcome. Thus, the reduced slope of the energy barrier in those conditions translates into facilitation of the hemifusion process and subsequently fusion in absence of applied compression. Moreover, given the lower slope of the barrier, the force requirements to induce hemifusion would be even lower during accelerated fusion under compression, which is indeed the case in the above described experiments [Fig. 6c].

TABLE 1.

Temperature and cholesterol concentration dependence of hemifusion energy barrier parameters.

| DPMC at temperature | Egg PC + % cholesterol | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17°C | 30°C | 5% | 10% | 15% | 20% | 25% | 30% | 40% | 67% | |

| xϕ(Å) | 0.45 | 1.04 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 1.21 | 1.04 | 0.77 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.37 |

| (S−1) | 3.70 | 3.36 | 2.59 | 2.38 | 1.73 | 2.03 | 2.24 | 4.47 | 2.47 | 3.13 |

5. SNARE-Mediated Fusion of Lipid Bilayers

In biological systems, SNARE proteins drive vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane by reducing the free energy cost for the overall process; however, it is not currently entirely clear how this is brought about. Therefore, an investigation of the mechanism(s) for SNARE-mediated lipid bilayer fusion was undertaken using the above described experimental system. Force measurements of the required compression force to induce hemifusion and fusion were obtained in the presence of SNAREs in the lipid bilayers; v- and t-SNAREs were reconstituted into the lipid vesicles 7,75), and the v-SNARE (VAMP) bilayers were formed on the glass microbead attached to the cantilever tip and the t-SNARE (syntaxin/SNAP-25) bilayers were formed on the glass dish by the vesicle adsorption method 49). Compression force measurements were acquired under different compression rates. The DFS revealed a significant reduction in the compression force required to induce hemifusion over the entire range of the compression rate when the v- and t-SNAREs were present in the opposite bilayers as compared to the SNARE-free bilayers [Fig. 7a]. However, the absence of VAMP from the bilayers on the microbead eliminated the observed reduction in the compression force. Moreover, the addition of the soluble cytoplasmic domain of VAMP (cd-VAMP) or treatment with botulinum neurotoxin B (BoNT/B) interfered with the observed reduction in the compression force required to induce hemifusion [Fig. 7b]. Further perturbations of the SNARE interaction by removing SNAP-25 or substituting it with truncated mutant forms (mut1-SNAP-25 or mut2-SNAP-25) which mimic the cleavage of SNAP-25 by BoNT/E and A, respectively, also interfered with the observed reduction in the compression force required to induce hemifusion [Fig. 7b]. Based on these results, it was revealed that the SNARE-mediated membrane fusion transitions through an intermediate hemifused state and that the trans-SNARE pairing is required to facilitate membrane hemifusion and subsequently fusion in this experimental system.

Fig. 7.

(a) Dynamic force spectra of the hemifusion process for egg PC bilayers with and without SNAREs. The compression force required to induce hemifusion is significantly reduced when v- and t-SNAREs are incorporated in the opposite bilayers, respectively. Interaction between the opposite v- and t-SNAREs is inhibited by the cytoplasmic domain of VAMP (cd-VAMP) and consequently the observed reduction in the compression force is abolished. (b) Similarly, truncating SNAP-25 by mutations or VAMP by BoNT/B interfered with the SNARE interaction and increased the compression force required to induce hemifusion of egg PC bilayers. Lines are fits of eq. (1) to the data points. Error bars are the s.e.m.

The observed facilitation in the hemifusion process in the above results in the presence of SNAREs in the bilayers is also reflected in the energy barrier parameters (xϕ and ) derived from fitting eq. (1) to the DFS under the different conditions of the SNARE bilayers (Table 2). It is evident in Table 2 that the hemifusion energy barrier width is increased significantly in the presence of native SNAREs. As mentioned above, the increase in the width of the hemifusion barrier reduces its slope, which translates into a facilitation of the overall fusion process in the absence of applied compression. Moreover, the increase in the hemifusion rate (; Table 2) reveals that the hemifusion process is further facilitated by the cognate SNARE interaction across the apposed bilayers. The combined effects of the reduced slope and height of the hemifusion energy barrier are depicted in Fig. 8a of the energy landscape. Using eq. (2), a difference (δΔG) in the height of the energy barrier of ~ 1.3 kBT is calculated between the SNARE-free and the SNARE-containing bilayers. The kinetic profile of the hemifusion process shows an initial ~ 4 fold increase in the hemifusion rate in the absence of applied compression when SNAREs are in the bilayers [Fig. 8b]. However, the rate increases exponentially with the applied compression which magnifies, under accelerated conditions, the facilitation in bilayer fusion mediated by SNAREs.

TABLE 2.

Energy barrier parameters for bilayer SNARE-mediated hemifusion and dissociation of the SNARE complex.

| Bilayers | xϕ(Å) | (S−1) | xβ1(Å) | (S−1) | xβ1(Å) | (S−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNARE-free | 0.31 | 0.57 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| v- / t-SNARE | 0.85 | 22.5 | 0.17 | 7.65 | 1.59 | 0.29 |

| v- / t-SNARE (no SNAP-25) |

0.52 | 10.22 | 0.40 | 8.47 | 1.70 | 0.39 |

| v- / t-SNARE (mut1-SNAP-25 |

0.37 | 7.74 | 0.97 | 15.6 | 3.18 | 0.21 |

| v- / t-SNARE (mut2-SNAP-25 |

0.47 | 5.97 | 0.46 | 14.3 | 2.17 | 0.34 |

| v- / t-SNARE (BoNT/B) |

0.53 | 19.14 | 0.37 | 20.1 | 2.32 | 0.46 |

k° is the dissociation rate of the activation barrier for fusion (ϕ) and unbinding (β), and the indices, 1 and 2, refer to the inner and outer barrier of the SNARE complex, respectively. x describe the width of the fusion (ϕ) and unbinding (β) energy barrier.

Fig. 8.

(a) Energy landscape of SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. The combined effects of the SNAREs on the hemifusion activation barrier width and height result in a significant reduction in of energy requirements for membrane fusion when compared to SNARE-free bilayers. (b) The SNARE-mediated facilitation in the membrane hemifusion is evident in the kinetic profiles for egg PC bilayers with SNAREs (dotted line) and without SNAREs (solid line); a 4 fold increase in the hemifusion rate is initially observed in the absence of applied conpression and the rate increases exponentially under accelerated conditions with applied force.

Given that apposition of the bilayers in above described experimental system is accomplished by the AFM-applied compression and that the reduction in the compression force required to induce hemifusion was observed only in the presence of intact SNAREs, it was suggested that the mere presence of SNAREs in the bilayers is insufficient to promote membrane fusion and that the interactions of the cytoplasmic domains of trans-SNAREs are required to facilitate the process. In an effort to investigate the effect of the interaction of the cytoplasmic domains between trans-SNAREs on hemifusion and subsequently membrane fusion, force measurements of the unbinding force of the trans-SNARE complex in the lipid bilayers were acquired using AFM force spectroscopy.

6. Dynamic Strength of the SNARE Complex

It has been shown that the evidence thus far suggest a critical role for the interaction of trans-SNAREs in mediating membrane fusion 49). Such proposition was further addressed by examining the hypothesis whether interfering with the interaction between SNAREs compromises their ability to mediate membrane fusion. The working hypothesis is that modification of the binding strength of the SNARE complex should modify the effect of the SNARE interaction on the facilitation of lipid bilayer fusion observed in the above experimental system. To test this, the mechanical strength of the SNARE interaction was determined by single molecule AFM force measurements of the unbinding of the trans-SNARE complex. Unbinding force measurements of the unitary SNARE interaction were acquired by AFM force spectroscopy using v- and t-SNAREs reconstituted into lipid bilayers that were formed on the glass microbead attached to the cantilever tip and the glass dish, respectively. As described above, during approach of the cantilever toward the substrate in the presence of opposing v- and t-SNARE bilayers, interaction between the opposite VAMP and binary syntaxin/SNAP-25 complex leads to the formation of a trans ternary SNARE complex, while the apposed v- and t-SNARE bilayers are compressed together. Binding of trans-SNAREs in the bilayers is confirmed by the presence of adhesion (i.e., unbinding) in the retraction trace of the AFM force scan [i.e., force versus piezo displacement curve; Fig. 9a]. It should be noted that unbinding events were only observed when SNAREs were present in the opposite bilayers, which confirmed the specificity of the observed adhesions to the trans-SNARE complexes in the bilayers. In the retraction trace of the force scan, the downward deflection of the cantilever is due to binding of the SNARE complex which leads to an increase in the force, in opposite direction to that during approach, as the SNARE complex is extended. With continued retraction of the cantilever, the SNARE complex is stressed until it no longer can hold together and de-adhesion (i.e., unbinding of the SNARE complex) occurs. The unbinding force fu is measured at the beginning of the de-adhesion process [Fig. 9a].

Fig. 9.

Dynamic strength of the SNARE complex. (a) AFM force scan showing the force vs. piezo-displacement curve between apposed floating lipid bilayers containing SNAREs. The forced unbinding of the SNARE complex formed the v- and t-SNAREs in the opposite bilayers occurs during retraction of the AFM cantilever away from the substrate. fu is the unbinding force of the SNARE complex. (b) Dynamic force spectra for the unbinding of the SNARE complex with and without SNAP-25. An outer and an inner barrier activation barrier were revealed during the slow and fast loading regimes, respectively. The higher unbinding forces in the fast loading regime indicate a strong binding interaction of the native v-/t-SNARE complex due to the steeper inner barrier. (c) This is evident in the energy landscape for the unbinding of the SNARE complex with and without SNAP-25. Omission of SNAP-25 from the SNARE complex widened the inner activation barrier and resulted in reducing its slope and, consequently, a weaker interaction.

In these unbinding experiments, a dynamic force approach was used to obtain the DFS for the unbinding process of the SNARE complex. Different loading rates were accomplished by varying the scan velocity during retraction of the cantilever away from the substrate. The DFS revealed two loading regimes, a slow and a fast one, where the unbinding force increased linearly with the logarithm of the loading rate [Fig. 9b]. The presence of two loading regimes is consistent with an unbinding process whereby the fully assembled SNARE complex must overcome at least two prominent activation barriers; first, an inner barrier (during fast loading rates) and subsequently an outer barrier (during slow loading rates) before the v- and the t-SNAREs are dissociated. In the context of the dynamic compression model described above, a similar approach can be used toward a dynamic pulling force 73,74) where a pulling force across the SNARE complex tilts the energy landscape, suppressing the outer barrier to a greater extent than the inner barrier. At large pulling forces the outer barrier is completely suppressed, allowing the inner barrier to govern the dissociation kinetics of the complex. Parameters characterizing the dissociation rate in the absence of applied pulling ( and xβ) of both the inner and outer energy barriers (Table 2) can be obtained by fitting Eq. 1 to the AFM unbinding force measurements from the fast and slow loading regimes of the DFS, respectively 76). With the assumption that the binding and the unbinding of the SNARE complex follow equal and opposite paths in the energy landscape, the unbinding force measurements reveal a strong binding interaction of the ternary SNARE complex comprising VAMP 2 (v-SNARE) and the binary syntaxin 1A/SNAP-25 complex (t-SNAREs).

Next, the effects of manipulating the individual SNAREs on the overall mechanical strength of the ternary v-/t-SNARE complex were investigated. Unbinding force measurements of the v-/t-SNARE complex pursuant to perturbations to either VAMP 2 or SNAP-25 were acquired. The measured unbinding force was significantly reduced after treatment of VAMP with BoNT/B [Fig. 9b]. Similarly, substitution of the full-length SNAP-25 in the binary syntaxin/SNAP-25 complex with either mut1-SNAP-25 or mut2-SNAP-25 resulted in a significant reduction of the unbinding force of the SNARE complex. Moreover, t-SNARE bilayers containing syntaxin, but not SNAP-25, interacted specifically with opposing v-SNARE bilayers containing VAMP 2, though the unbinding forces were lower than those in the presence of full-length SNAP-25 [Fig. 9b]. The observed reduction in the unbinding force under these conditions indicates a weaker SNARE binding interaction. Moreover, such reduction in the unbinding force is most significant during the fast loading regime revealing more pronounced effects on the inner energy barrier by the SNARE perturbations [Fig. 9c]. This suggests a principal role for the inner energy barrier in contributing to the mechanical strength of the SNARE complex.

It was shown above that similar perturbations to the SNAREs in the bilayers interfere with the observed reduction in the compression force required to induce hemifusion of the bilayers. Together with the results from the SNARE unbinding experiments, these findings reveal an inverse relationship between the mechanical strength of the SNARE interaction and the compression force required to induce hemifusion of the membranes.

7. Correlation between the Pulling Force of the SNARE complex and Bilayer Fusion

To determine whether there is a direct correlation between the pulling force of the SNARE complex and the suppression in the membrane fusion force requirements by SNAREs, it is important to first establish parameters that properly describe the pulling force generated during the SNARE complex formation and the extent of facilitation of membrane fusion. The interpretation of the unbinding energy landscape is that the outer activation barrier governs the SNARE binding affinity while the steep inner barrier mainly determines the mechanical strength of the SNARE interaction and provides the pulling force necessary to pin the membranes together during SNARE-mediated fusion. The pulling force of the interacting SNAREs fπ can be estimated by the product of the reduced unbinding force (fβ) and the overall height of the inner barrier (ΔE1 in units of kBT) of the SNARE complex: fπ = fβ × ΔE1. fβ corresponds to the pulling force required to suppress the inner activation barrier by 1 kBT during forced unbinding. It is also the pulling force generated as the interacting SNAREs transition from the peak of the inner activation barrier to the bound state by an amount equivalent to 1 kBT in the energy landscape. In the context of the above described model 77), fβ equals kBT divided by xβ1, where xβ1 is the molecular distance between the bound and the transition state at the peak of the inner barrier (i.e., inner barrier width). Experimentally, xβ1 and hence fβ can be determined by fitting eq. (1) to the acquired unbinding force spectra of the SNARE complex under the different conditions; fβ is 240 pN for the native SNARE complex. Moreover, an estimate of the absolute height of the inner barrier of the SNARE complex can be obtained from the difference between the binding energy of the complex and the energy separation between the inner and outer barriers 77). The binding energy of the SNARE complex was estimated to be ~ 35 kBT 78). Using the k°β1 and k°β2 values derived from the forced unbinding measurements (Table 2), a difference (δΔG) of ~ 3.3 kBT is obtained between the outer and inner barriers [see eq. (2)] and, hence, an estimate of ~ 32 kBT for the height of the inner barrier. Thus, the estimated pulling force of the native SNARE complex is 7.68 nN.

Similarly, the reduced hemifusion force (fφ) and the height of the hemifusion barrier can be used to estimate the force required to induce hemifusion of the membranes. fφ corresponds to the compression force required to overcome 1 kBT of the hemifusion energy barrier and is obtained experimentally from fitting the dynamic compression model [eq. (1)] to the force spectra of membrane hemifusion under the different conditions. fφ can also be obtained from dividing kBT by xϕ, where xϕ is the width of the hemifusion activation barrier under the different experimental conditions (see Table 2). In the extreme cases presented here, fφ ranges from 48 pN for the hemifusion of native t-/v-SNARE bilayers to 110 pN for SNARE-free bilayers. A lower value of fφ indicates that less force is required to induce hemifusion. Since the overall height of the hemifusion barrier (ΔEφ) is estimated to be ~ 45 kBT 79), the compression force fC needed to completely suppress the hemifusion barrier is 2.16 nN (fC = fφ × ΔEφ) for SNARE-mediated fusion in the AFM experimental system. In contrast, over 5.9 nN is required to suppress the hemifusion barrier in the presence of SNARE-free bilayers (Fig. 10).

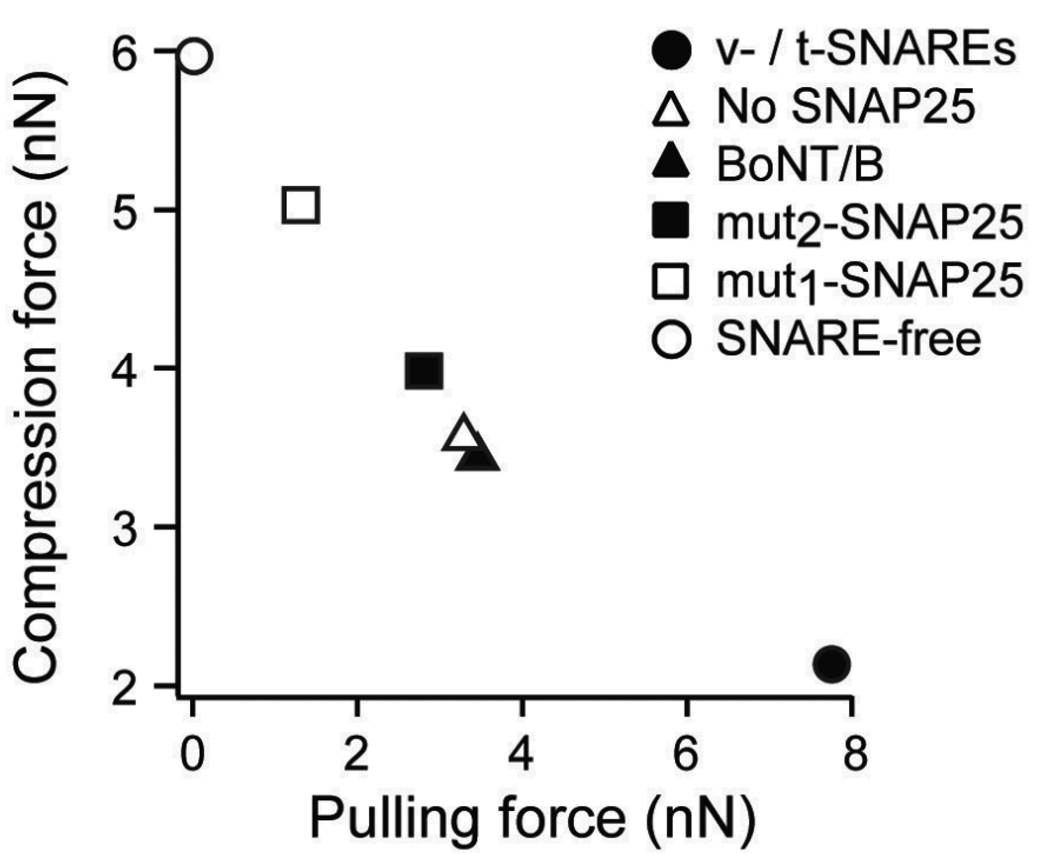

Fig. 10.

Membrane fusion facilitation quantified by the compression needed to induce hemifusion (fC) correlates with the binding force generated by interacting SNAREs as characterized by the SNARE pulling force (fπ)

Figure 10 plots the compression force fC versus the pulling force fπ for the different SNARE combinations characterized in the AFM lipid bilayer experimental system. The strong correlation between fC and fπ is interpreted as evidence that, in addition to providing critical proximity between the membranes, the formation of the trans-SNARE complex facilitates their hemifusion and subsequently fusion.

8. Summary

It was shown that the current findings are consistent with a multistep model for membrane fusion. The initial trans-interaction of cognate SNAREs brings the opposing bilayers to close proximity; this step corresponds to the transition of the dissociated SNAREs over the outer activation barrier to a transient intermediate bound state between the outer and inner energy barriers of the complex. In neurons for example, this intermediate state corresponds to the primed state of docked vesicles and might be stabilized by complexin 80–82) or synaptotagmin as recently suggested 83). Nonetheless upon stimulation and intracellular Ca2+ increase, release of the constraint on the molecular system occurs 84–87), and the SNARE complex is allowed to cross over the inner activation barrier toward a tightly bound state. The strong pulling force generated as the system moves down the steep inner barrier induces conformational changes in the juxtamembrane and transmembrane domains of the SNAREs 88). Consistent with the role of tilted peptides 45,89) and viral fusion proteins in destabilizing the lipid bilayers and facilitating viral fusion with the host cell membrane 90,91), such pulling force can lead to local destabilization of the lipid bilayers at SNARE anchorage points and, subsequently, to facilitation of membrane fusion at fusion sites 49).

In summary, a novel experimental membrane system was established where hemifusion and fusion of floating lipid bilayers can be induced by compression and the associated compression forces can be measured using AFM force spectroscopy. This system was used to investigate the mechanism(s) of membrane fusion using protein-free and SNARE-containing lipid bilayers. It was revealed that a significant reduction in the overall energy requirements for membrane fusion occurs with increased fluidity of the membranes by either temperature or lipid composition. More importantly, a SNARE-mediated facilitation of membrane hemifusion and subsequently fusion was revealed due to trans-SNARE pairing in the apposed bilayers. In both cases, increased fluidity and SNARE proteins in the bilayers, fusion facilitation was brought about mainly by reducing the slope of the energy barrier in the energy landscape of the hemifusion process. Moreover, single unbinding forces of SNARE complexes anchored in the opposite lipid bilayers were measured using the same experimental system. The results revealed a strong binding interaction between cognate SNAREs. The data from the compression and unbinding experiments have lead to the establishment of a direct correlation between the mechanical strength of the SNARE interaction and the SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Taken together, the current findings support a critical role for the trans-SNARE interaction in mediating membrane fusion by pinning the opposing membranes at close proximity and locally destabilizing the lipid bilayers at fusion sites making the membranes more prone to hemifusion and subsequently fusion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (GM55611 and GM086808). We are grateful to our collaborators, Drs. E. Chapman and A. Bhalla, for the SNARE vesicles and insightful input and feedback.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blumenthal R, Clague MJ, Durell SR, Epand RM. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:53. doi: 10.1021/cr000036+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chernomordik LV, Kozlov MM. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fardon NJ, Wilkinson R, Thomas TH. Am. J. Hypertension. 2001;14:927. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lentsch AB, Ward PA. J. Pathol. 2000;190:343. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<343::AID-PATH522>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber T, Zemelman BV, McNew JA, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. Cell. 1998;92:759. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu T, Tucker WC, Bhalla A, Chapman ER, Weisshaar JC. Biophys. J. 2005;89:2458. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhalla A, Chicka MC, Tucker WC, Chapman ER. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:323. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nickel W, Weber T, McNew JA, Parlati F, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:12571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ungar D, Hughson FM. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;19:493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.155609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman JE. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1994;29:81. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(06)80008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunger AT. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2005;38:1. doi: 10.1017/S0033583505004051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sollner T, Whiteheart SW, Brunner M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Geromanos S, Tempst P, Rothman JE. Nature. 1993;362:318. doi: 10.1038/362318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT. Nature. 1998;395:347. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman ER. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:498. doi: 10.1038/nrm855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson MB, Chapman ER. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2006;35:135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu X, Zhang F, McNew JA, Shin YK. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon TY, Okumus B, Zhang F, Shin YK, Ha T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:19731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606032103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jahn R, Lang T, Sudhof TC. Cell. 2003;112:519. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reese C, Mayer A. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards DA, Bai J, Chapman ER. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:929. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang CT, Lu JC, Bai J, Chang PY, Martin TF, Chapman ER, Jackson MB. Nature. 2003;424:943. doi: 10.1038/nature01857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fulop T, Radabaugh S, Smith C. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2042-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harata NC, Aravanis AM, Tsien RW. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:1546. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aravanis AM, Pyle JL, Harata NC, Tsien RW. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:797. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00310-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han X, Wang CT, Bai J, Chapman ER, Jackson MB. Science. 2004;304:289. doi: 10.1126/science.1095801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monck JR, Fernandez JM. Neuron. 1994;12:707. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters C, Bayer MJ, Buhler S, Andersen JS, Mann M, Mayer A. Nature. 2001;409:581. doi: 10.1038/35054500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindau M, Almers W. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1995;7:509. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroch AE, Fleming KG. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:184. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann MW, Peplowska K, Rohde J, Poschner BC, Ungermann C, Langosch D. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;364:1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy R, Laage R, Langosch D. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4964. doi: 10.1021/bi0362875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson MB. Biophys. Chem. 2007;126:201. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jena BP. J. Endocrinol. 2003;176:169. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1760169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho SJ, Kelly M, Rognlien KT, Cho JA, Horber JK, Jena BP. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2522. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin RC, Scheller RH. Neuron. 1997;19:1087. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudhof TC. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:7629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutton RB, Ernst JA, Brunger AT. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:589. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugita S, Shin OH, Han W, Lao Y, Sudhof TC. EMBO J. 2002;21:270. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thongthai W, Weninger K. Photochem. Photobiol. 2009;85:801. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chapman ER, Hanson PI, Jahn R. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1343. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bacia K, Schuette CG, Kahya N, Jahn R, Schwille P. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chapman ER, Davis AF. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chae YK, Abildgaard F, Chapman ER, Markley JL. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:25659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowen M, Brunger AT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:8378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602644103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas A, Brasseur R. Curr. Protein Peptide. Sci. 2006;7:523. doi: 10.2174/138920306779025594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zwilling D, Cypionka A, Pohl WH, Fasshauer D, Walla PJ, Wahl MC, Jahn R. EMBO J. 2007;26:9. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorensen JB, Wiederhold K, Muller EM, Milosevic I, Nagy G, de Groot BL, Grubmuller H, Fasshauer D. EMBO J. 2006;25:955. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pobbati AV, Stein A, Fasshauer D. Science. 2006;313:673. doi: 10.1126/science.1129486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdulreda MH, Bhalla A, Chapman ER, Moy VT. Biophys. J. 2008;94:648. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McNew JA, Weber T, Parlati F, Johnston RJ, Melia TJ, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:105. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kesavan J, Borisovska M, Bruns D. Cell. 2007;131:351. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siddiqui TJ, Vites O, Stein A, Heintzmann R, Jahn R, Fasshauer D. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:2037. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rand RP, Parsegian VA. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1986;48:201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalb E, Frey S, Tamm LK. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1103:307. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90101-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heyse S, Vogel H, Sanger M, Sigrist H. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2532. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mueller H, Butt HJ, Bamberg E. Biophys. J. 1999;76:1072. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77272-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Subczynski WK, Wisniewska A. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2000;47:613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tokumasu F, Jin AJ, Feigenson GW, Dvorak JA. Ultramicroscopy. 2003;97:217. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3991(03)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Worsfold O, Voelcker NH, Nishiya T. Langmuir. 2006;22:7078. doi: 10.1021/la060121y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daillant J, Bellet-Amalric E, Braslau A, Charitat T, Fragneto G, Graner F, Mora S, Rieutord F, Stidder B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:11639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504588102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaizuka Y, Groves JT. Biophys. J. 2004;86:905. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74166-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fragneto G, Charitat T, Graner F, Mecke K, Perino-Gallice L, Bellet-Amalric E. Europhys. Lett. 2001;53:100. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maeda N, Senden TJ, di Meglio JM. Biochim. Biophys. Acta: Biomembranes. 2002;1564:165. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stidder B, Fragneto G, Cubitt R, Hughes AV, Roser SJ. Langmuir. 2005;21:8703. doi: 10.1021/la050611a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaasgaard T, Leidy C, Crowe JH, Mouritsen OG, Jorgensen K. Biophys. J. 2003;85:350. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74479-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leidy C, Kaasgaard T, Crowe JH, Mouritsen OG, Jorgensen K. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2625. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Giocondi MC, Le Grimellec C. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2218. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74280-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abdulreda MH, Moy VT. Biophys. J. 2007;92:4369. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.096495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pera I, Stark R, Kappl M, Butt HJ, Benfenati F. Biophys. J. 2004;87:2446. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.044214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Katsov K, Muller M, Schick M. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3277. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.038943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kozlovsky Y, Kozlov MM. Biophys. J. 2002;82:882. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75450-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Giraudo CG, Hu C, You D, Slovic AM, Mosharov EV, Sulzer D, Melia TJ, Rothman JE. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:249. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bell GI. Science. 1978;200:618. doi: 10.1126/science.347575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Evans E, Ritchie K. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1541. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78802-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tucker WC, Weber T, Chapman ER. Science. 2004;304:435. doi: 10.1126/science.1097196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evans E, Leung A, Hammer D, Simon S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:3784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061324998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wojcikiewicz EP, Abdulreda MH, Zhang X, Moy VT. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:3188. doi: 10.1021/bm060559c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li F, Pincet F, Perez E, Eng WS, Melia TJ, Rothman JE, Tareste D. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:890. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cohen FS, Melikyan GB. J. Membrane Biol. 2004;199:1. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carr CM, Munson M. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:834. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bowen ME, Weninger K, Ernst J, Chu S, Brunger AT. Biophys. J. 2005;89:690. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Melia TJ., Jr FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2131. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chicka MC, Hui E, Liu H, Chapman ER. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:827. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huntwork S, Littleton JT. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1235. doi: 10.1038/nn1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schaub JR, Lu X, Doneske B, Shin YK, McNew JA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:748. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tang J, Maximov A, Shin OH, Dai H, Rizo J, Sudhof TC. Cell. 2006;126:1175. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoon T, Lu X, Diao J, Lee S, Ha T, Shin Y. Nat, Struct, Mol, Biol. 2008;15:707. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McNew JA, Weber T, Engelman DM, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:415. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Crowet JM, Lins L, Dupiereux I, Elmoualija B, Lorin A, Charloteaux B, Stroobant V, Heinen E, Brasseur R. Proteins. 2007;68:936. doi: 10.1002/prot.21483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lorin A, Charloteaux B, Fridmann-Sirkis Y, Thomas A, Shai Y, Brasseur R. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:18388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lau WL, Ege DS, Lear JD, Hammer DA, DeGrado WF. Biophys. J. 2004;86:272. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74103-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]