Abstract

Background

Clinical trials (CT) serve as the media that translates clinical research into standards of care. Low or slow recruitment leads to delays in delivery of new therapies to the public. Determination of eligibility in all patients is one of the most important factors to assure unbiased results from the clinical trials process and represents the first step in addressing the issue of under representation and equal access to clinical trials

Methods

This is a pilot project evaluating the efficiency, flexibility, and generalizibility of an automated clinical trials eligibility screening tool across 5 different clinical trials and clinical trial scenarios.

Results

There was a substantial total savings during the study period in research staff time spent in evaluating patients for eligibility ranging from 165 hours to 1,329 hours. There was a marked enhancement in efficiency with the automated system for all but one study in the pilot. The ratio of mean staff time required per eligible patient identified ranged from 0.8 to 19.4 for the manual versus the automated process.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate that automation offers an opportunity to reduce the burden of the manual processes required for CT eligibility screening and to assure that all patients have an opportunity to be evaluated for participation in clinical trials as appropriate. The automated process greatly reduces that time spent on eligibility screening compared with the traditional manual process by effectively transferring the load of the eligibility assessment process to the computer.

Keywords: Clinical Trials, Eligibility, Automation

Background

Clinical trials (CT) serve as the media that translates research into standards of care. The efficacy of this translational process is greatly dependent on the number of participants enrolled in CT’s. It is estimated that less than 5% of all adult cancer patients enter clinical trials [1–3]. These low accrual rates represent a significant barrier to speeding progress in the “war on cancer” by delaying the dissemination of new therapies [2–5]. Low and slow recruitment impacts the translation of results through: inadequate statistical analyses of outcomes and premature closure of trials; longer trial duration; higher costs of drug production; and loss of accreditation of research centers that perform these studies [6–8]. Further, low recruitment in underserved populations leads to the appearance of inequalities in access to the latest technology and treatments. [9,10].

Determining eligibility in every patient is critical to assuring adequate and unbiased enrollment rates and represents the first step in addressing the issue of under representation in clinical trials [11–13]. Despite this, not all eligible patients are evaluated or invited to participate in a clinical trial even though patients who are offered a trial are likely to participate [14]. Currently there are no systematic audit data that define the population of patients evaluated for eligibility in clinical trials. The ability to capture these data is essential to assure that all potentially eligible patients are offered the opportunity to participate. Capturing the data is not simple. The complexity of the health care delivery system, the magnitude of clinical information, and patient population size preclude research staff from adequately and completely evaluating every patient.

Traditionally, research staff manually review multiple clinical data sources from the medical record. Potentially eligible patients are often missed through the manual process [15,16]. This problem is amplified if we consider that the efficiency of the manual method rapidly degrades with the increase in patient load and the number of clinical trials requiring review [17]. When the Clinical Research Staff (CRS) spend time assessing eligibility, they have less time to spend actually recruiting patients, further impacting enrollment rates. This is a particular challenge in large, complex and geographically dispersed academic health care centers. Yet they serve as one of the primary sources for the implementation of new health care technologies and treatment through their research enterprise [18,19].

Automated systems for eligibility screening using Health Information Technology tools present a promising solution to these logistical issues and are being developed and tested by academic health care centers [8,16,20–26]. Those reported to date have lacked the flexibility and generalizibility to enable them to be scaled and transported to other academic centers [[8,16,20–27].

In order to address many of the challenges in screening for clinical trials eligibility, we developed an integrated software application to automatically and routinely assess patients for eligibility across a broad range of clinical trial types. In this manuscript we report on a pilot study designed to evaluate the general functionality, efficiency, and flexibility of this automated screening tool.

Methods

To directly address barriers to rapid assessment of patients for clinical trials we developed an automated data searching and reporting tool which: 1) provides a reduction in the time required for repeated and ongoing eligibility screening, 2) uses algorithms to access and search multiple, commonly available electronic clinical data sources, and 3) has the ability to modify the automatching process and requirements as necessary to function across a variety of clinical trial types. The focus of the automated software was to permit research staff to quickly screen patients to overcome the barriers associated with the complex manual consolidation of health care data from multiple locations; the brief windows of opportunity during the patient’s therapeutic process; and assessing increasingly complex and specific eligibility requirements for clinical trials.

This tool builds on commonly available and standardized electronic data sources; transmits the pre-screened data directly to the appropriate research staff; and provides a linked tool to capture information on ultimate patient eligibility status or refusal. The latter component was designed to provide a feedback loop regarding the appropriateness of clinical trials for our patient population. The software tool was designed for flexibility of use across multiple diseases and across a variety of research studies. We focused on utilizing electronic data sources and systems that are commonly available across health care institutions to permit generalizibility.

a. Description of the automated eligibility screening software

The software functions by receiving information on a daily basis from the electronic scheduling system for the current date and the next 14 days on all patients with scheduled visits to a pre-defined set of physicians, clinics, or with a diagnosis of cancer. Additionally census data are received daily for patients admitted as inpatients to selected physicians or locations. Patients identified through these sources have their clinical information captured and linked on a longitudinal basis. These linked electronic data sources represent commonly available sources such as 837 billing data and HL7 reports. These do not require direct integration with an Electronic Medical Record (EMR). Data sources include inpatient, outpatient and professional billing (837formats) and HL7 records of surgical pathology reports, clinical laboratory test results, radiology reports, clinical dictations, operative notes and discharge summaries. The system has the capacity to add new sources as they become available, and does not require all sources to be available for its use. The requirement to maintain longitudinal data is essential to permit repeated determination of the patient’s eligibility status over the course of the disease. For example, if a patient is required to have active or progressive disease to be eligible, the clinical pathology test results for a tumor marker will be screened, and a patient identified as potentially eligible when the tumor marker level reaches the threshold indicated in the selection criteria. Data used in the automated matching process represent electronic sources that are routinely available such as billing and pathology information. Although <2% of health care systems have a fully implemented EMR, all hospitals and medical professionals are required by Medicare to bill electronically using a standardized format (837). Additionally more than 75% of hospitals have pathology and radiology reporting systems available in an electronic format [28].

b. Automated eligibility screening processes

Data are screened in two steps. First, patient characteristics are screened and matched with discrete, standardized, or numeric data. Match characteristics evaluated from these data sources include: demographics from the registration (scheduling) system, diagnosis from pathology or billing, comorbidity, and prior and current treatment from the billing data, and comorbidity and clinical status from the clinical laboratory data. The demographic data available include age, race, gender, insurance, and marital status. Patient contact information such as address and cell phone are available and captured for transmission to the clinical research staff from the scheduling system. Billing data are universally available in a standardized format and include standardized data on diagnoses for current diagnosis and comorbidity and detailed treatment information. These data elements are extracted from International Classification of Disease 9th revision (ICD-9) Diagnosis and Procedure codes and Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes. The billing data have been demonstrated to have a high sensitivity, specificity, and validity for use in capturing information on cancer patients [29–34]. Clinical laboratory test results are screened for clinical status and include measures of renal function, hematologic indices, tumor markers, etc. that can be utilized to include or exclude patients for a study.

A major challenge for clinical research staff is the requirement for ongoing evaluation of patients throughout the course of their disease. Because patients may enter the system through different clinical areas, or become eligible based on data from a variety of electronic sources, the automated screening process uses any change in a relevant eligibility criteria to initiate a new screen. For example, if a patient is identified as having a new billing code for a specific chemotherapy agent that is an inclusion criterion for a study, that patient is then screened and re-evaluated for potential eligibility. If a new pathology report or clinical laboratory test result demonstrates a change in the patient’s clinical status (i.e. recurrence based on new surgical pathology report or increase above normal in a serologic tumor marker) that patient would then be automatically screened to re-assess them for eligibility. The system is flexible in that it will permit a patient to enter the queue for screening from any data source or change in status from existing data.

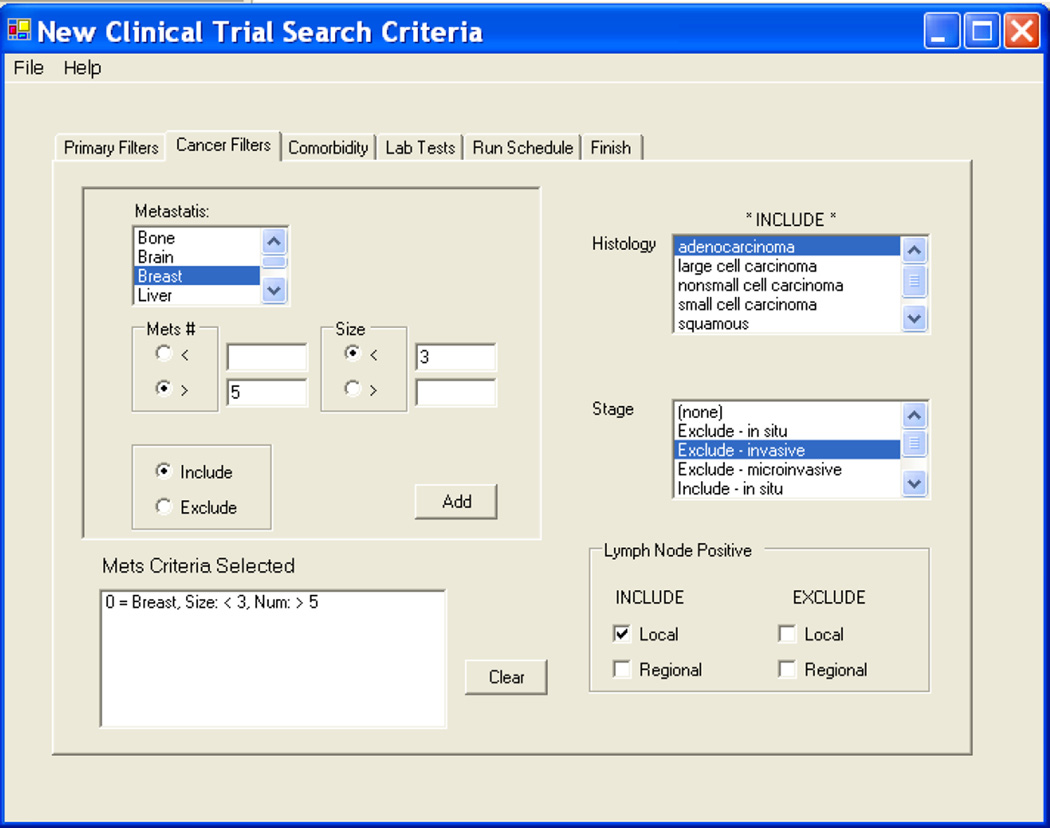

Once the discrete data are processed and the relevant patient population reduced (i.e. if the study requires only women, all men are excluded thus reducing the subsequent patients to be screened under the second algorithm by 50%.) The second step screens text-based HL7 messages representing dictations from surgical pathology to identify and match on the detailed cancer-related clinical characteristics of the cancer. The system utilizes a matching algorithm that finds particular strings within a large string of text to identify other clinical criteria. The surgical pathology reports for solid tumors use a manually formatted synoptic checklist format. This permits identification of the tumor size, number of lymph nodes positive either under the pathology staging (pTx, pNx, pMx), or by simply searching the free text for the “Tumor Size” or “Lymph Nodes” section of the pathology report. The algorithm was originally tested and developed for automated processing of pathology reports for our cancer registry through iterative testing coupled with manual review of pathology reports. The text strings were selected from pre-defined lists developed by subject matter experts (cancer registrars and CRS) experienced in screening text reports for cancer relevance. The surgical pathology report is used to identify histopathologic characteristics, staging and surgical procedures. An example of a screen that a CRS would use to select patient criteria from the surgical pathology reports (tumor characteristics) is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Screen shot from the User Interface to select eligibility criteria related to tumor characteristics from the surgical pathology report.

c. Automated data screening and electronic delivery of results

The automated screening is performed on a schedule determined by the research staff. The software evaluates all patients currently in the system or scheduled for an upcoming visit and compares all the clinically relevant information against the eligibility criteria entered for that study. Once the prescreening for eligibility is performed, and a set of patients are defined as potentially eligible, the relevant list of patients is transmitted via secure, encrypted email to the key individuals who would utilize the information – the study clinical research staff and the principle investigator. The data included in this list are determined by the research staff. An example of a list that is automatically generated for adjuvant breast cancer treatment trials is included below in Table 1. Data requested for this query include breast cancer patients with specific tumor characteristics, patient demographics, and scheduled visit date. In this instance, the list is run for patients with a visit scheduled in the next two weeks.

Table 1.

Generic query results auto-generated and transmitted via secure email to the clinical research staff for adjuvant breast treatment trials.

| M R N | REPORT Date |

Last Name | First Name | Organ Site / Specimen Type |

Patient DOB |

Accession* | Report Type | Tumor Size | NODE | ER ** | PR ** | H E R 2** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 / 26 / 2007 | HELEN | BRST LT SEG | SP-07-16210 | SP Final Report | 0.9×0.8×0.6cm | pNx | 60% | 90% | Negative | |||

| 12/31/2007 | JAMES | CONSULT SLIDES | CS-07-01264 | Consult Final Report | 1.3 cm | pN0 | 0% | 25% | Negative | |||

| 12/31/2007 | PEGGY | CONSULT SLIDES | CS-07-01265 | Consult Final Report | 2.2×1.1×0.8cm | pN1 | 80% | 90% | Negative | |||

| 12/27/2007 | CATHERINE | BRST CORES LT | SP-07-16270 | SP Addendum Report | ptor | 1% | 0% | |||||

| 12/27/2007 | MARY | BRST CORES LT | SP-07-16272 | SP Addendum Report | ptor | 0% | 0% | |||||

| 1/7/2008 | ANNE | BRST RIGHT | SP-08-00199 | SP Final Report | 0.9×0.7×0.6cm | pN0 | 95% | 95% | Negative | |||

| 1/7/2008 | GERTRUDE | BRST RIGHT | SP-08-00216 | SP Final Report | largest residual focus 0.6 cm | pN ( | 90% | (0% | Negative | |||

| 1/8/2008 | PAMELA | CONSULT SLIDES | CS-08-00013 | Consult Final Report | Two foci, one at 1.5 cm | pN0 | Negative | Negative | ||||

| 1/9/2008 | JUDITH | BRST LEFT | SP-08-00330 | SP Final Report | PTIO | |||||||

| 1/7/2008 | JACQUELINE | BRST CORES RT | SP-08-00233 | SP Addendum Report | ptor | 90% | 10% |

Query automatically generated weekly and emailed in HIP AA compliant secured file to Project CRNs and P is

Accession number permits the CRNs to review report directly if required

ER = Estrogen Receptor, PR = Progesterone Recepter, HER2/Neu = Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2

d. Study Design

Although the ultimate purpose of the system is to enhance representative participation and accrual in clinical trials, the primary objective of the software tool was to provide an efficient method to quickly identify a list of potentially eligible patients for our clinical research staff to further evaluate. In order to evaluate the utility of the system we performed a pilot test to evaluate the effectiveness of this system using five different clinical trials or clinical trial scenarios. The reasons for including each of the clinical trials and the attributes evaluated through the use of these studies are reported in Table 2. Below is a brief summary of each of the studies or clinical trial scenarios; and a brief description of the challenge faced by the clinical research staff related to the specific study or study scenario. The data collection interval varied for each study, ranging from 25 weeks to 10 months.

Table 2.

Characteristics of test studies for evaluating the automated matching process

| Test Study 1 | Test Study 2 | Test Study 3 | Test Study 4 | Test Study 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Description | Randomized Phase III, Neoadjuvant Chemo - therapy in Breast Cancer. Evaluating effect on pCR of adding Gemcitabine to Docetaxel when administered before AC | Study to evaluate the impact of primary insurance in employed and insured women with early stage breast cancer | Reporting patient data on selected common criteria and results for women scheduled to the multi-disciplinary breast clinic. To assess eligibility for all adjuvant treatment trials | Early identification of patients admitted for acute hematologic malignancies: Designed to capture patients prior to initiation of therapy for assessing eligibility to multiple Phase I-Phase III studies for leukemias and lymphomas. | Study of symptom onset and reporting among patients with early stage colon and rectal cancer. |

| Study Type | Therapeutic Treatment Trial | Health Care Policy/Cancer Prevention and Control Study | Multiple Treatment Trials single cancer site | Therapeutic Phase I and Phase II Trials multiple cancers | Cancer Prevention and Control Study |

| System At tribute Tested | Screen and process data from multiple sources for clinical characteristics | Screen and process data from multiple sources for demographics | Screen patients prospectively (appts. Scheduled in upcoming weeks) | Screen and link data from new data source (Inpatient Census) | Identify patients seen within & outside cancer clinics with specific clinical characteristics |

| Capture and translate com orbidity and clinical information from billing & labs to patient eligibility characteristics | Capture patients from multiple entry points in to the clinical system | Capture & present patient data matching multiple clinical trials efficently | Linking External data source with existing data in software | Provide research staff with patient data on clinical status (where diagnosed) and contact information | |

| Linking both prospective & retrospective clinical in formation | Identify patients in short interval from diagnosis (< 60 days) | Effectiveness of NLP* for matching with specific tumor characteristics in text based reports | Capture patients for generic multi- trial/multi-cancer utility | Screen and identify patients with in a short interval from diagnosis (30 days) | |

| Screening Challenge Addressed | Ongoing clinical trial with complex clinical criteria requiring assessment of treatment history, selected and specific comorbid conditions and tumor characteristics. System screened past treatment through billing , comorbidity through | Patients entered system through multiple clinics no method for identifying patients receiving only chemotherapy or radiation therapy. System identifies patients with in 60 days of new on set radiation or chemotherapy treatment | Research staff used manual grid for evaluating eligibility for multiple adjuvant breast trials-challenge capturing all relevant clinical data prior to clinic visit. Automated report consolidates and presents data for all criteria in grid for scheduled | Clinic based research staff unable to rapidly identify newly diagnosed patients with hematologic malignancy admitted for treatment System captures daily census, screens for patients admitted for | Newly diagnosed early stage colorectal cancer patients not captured through scheduled multi- disciplinary or other cancer clinics because diagnosis through gastroenterology. System expanded to include patients with |

| Sources of Clinical Information | Patient scheduling , Clinical Pathology, surgical pathology, Billing; Patient demographics table | Patient Scheduling; Billing; surgical pathology; Patient demographic stable | Surgical Pathology Reports, Patient demographics table, Scheduled visits data | Daily Inpatient Census, Patient demo graphics table, clinical laboratory test | Pathology reports, scheduled visits |

NLP = Natural language Processing

Study 1 (NSABP B40) is a study of a neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with breast cancer and represents a traditional treatment trial with modestly stringent eligibility criteria. Inclusion of this study permitted us to evaluate the use of multiple clinical data sources (flexibility) for rapid and efficient automated screening of all breast cancer patients (efficiency). Data sources included surgical pathology reports, clinical pathology test results, and billing data. This study had relatively complex eligibility criteria including diagnostic criteria, prior treatment, exclusion criteria related to co-morbidity, and selected demographic characteristics.

Study 2 is a health services research / health policy study and was included to assess the utility of the system in rapid capture of patients with specific diseases entering the system through less traditional routes (not breast multi-disciplinary clinics). Searching only the pathology database and attending the multidisciplinary breast conference missed newly diagnosed patients who were referred to our facility for adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy. This study also used non-clinical eligibility parameters such as insurance and employment.

Study 3 was included to assess the ability of the system to capture a more generic selection of patients potentially eligible for more than one clinical trial for a specific disease. The CRS developed a grid of eligibility requirements common to multiple clinical trials for adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. These eligibility requirements included tumor attributes such as histologic diagnosis, estrogen receptor, tumor size, etc. A query was developed based on those criteria and a list is generated weekly that includes all breast cancer patients’ data on those 7 clinical parameters from which eligibility is determined. This automatch takes into account the eligibility criteria as well as patient scheduling to the breast multi-disciplinary clinic. An example of the report generated via this query is provided in Table 1.

The last two examples (Study 4 and 5) were selected to assess the flexibility for adding new data components and fields and for assessing the “real time” capability of the system. For these studies, patients were not identifiable through data routinely captured via our scheduling system.

For Study 4 a new query was developed to capture and pre-screen inpatients admitted acutely for treatment of hematologic malignancies. These acutely ill patients were being admitted, and treatment was initiated prior to the research nurse becoming aware of their presence, thus bypassing the opportunity for clinical trial enrollment. There was no way to easily capture or identify these patients routinely as a group using the existing EMR or Decision Support systems. In order to meet the needs of this research group, we modified the existing query system to capture daily inpatient census for all admissions to the hospital; subsetting the data as appropriate to patients with hematologic malignancies; and sending results to both clinicians and to CRS responsible for clinical trials for patients with hematologic malignancies. The census data are provided in near real time on a daily basis and automatically provide a pre-screened population that can be further evaluated for eligibility in a variety of Phase I and other clinical trials for newly diagnosed leukemia and lymphoma patients.

Study 5 is also a cancer prevention and control research study to evaluate symptom onset in patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer. The short time interval (30 days from diagnosis) and the frequent delay or absence of these patients from the oncology multi-disciplinary schedule required expanding the data sources and criteria searched for potential eligibility. While apparently simple, capturing the initial date of diagnosis on a real time basis is challenging in a tertiary referral academic health center due to the complexity of the systems involved in diagnosing the patient.

The specific eligibility criteria for each study that were programmed into the system for automated matching are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Eligibility criteria for auto matching process by study.

| Eligibility Criteria | Study 1, NSABP B40 | Study 2. Breast Cancer .and Insurance |

Study 3. Generic Adjuvant Breast Protocols* |

Study 4. Acute Hematologic Malignancies* |

Study 5. Symptom Assessment in Patients with early stage Colorectal cancer |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Gender | F | F | F | |||

| Age | >=18 | >18 <60 | >18 | >18 | >18 | |

| Marital Status | NA | Married | NA | NA | NA | |

| Employment | NA | Employed | NA | NA | NA | |

| Insurance Status | NA | Private Primary | NA | NA | NA | |

| Interval Since Diagnosis | pre-treatment | <60 days | variable- dx date reported | pre-treatment | <30 Days | |

| Treatment | Biopsy only | Not Palliative | variable | no treatment | NA | |

| Surgical Procedure | Core Biopsy | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Chemotherapy | exclusion | permitted <= 60 days | exclusion | exclusion | ||

| Radiation Therapy | exclusion | permitted <= 60 days | exclusion | exclusion | ||

| Cancer Site | Breast | Breast | Breast | Leukemia/ Lymphoma | Colon and rectal | |

| Histology | adenocarcinoma | NA | variable - reported | variable - reported | NA | |

| Other Tumor Characteristics | ||||||

| Tumor Size | >2.0 CM | NA | variable - reported | NA | NA | |

| Stage | noninvasive | nonmetastatic | variable | NA | nonmetastatic | |

| Tumor Markers | Her2Neu | NA | Her 2NEU, ER, PR,Her 2NEU, ER, PR, reported | NA | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Disease Exclusions | SLE, schleroderma | variable - reported | variable - reported | |||

| Hematologic Indices | ANC>1200 | NA | NA | variable- captured | NA | |

| Renal Function | Nl Renal Function | NA | variable-capture | variable- captured | NA | |

| Other Clinical Tests | ||||||

| Cardiac | ||||||

| EKG/Echo | NL EKG, LV EF | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

For study category 3 & 4 the data were presented rather than used as exclusion or inclusion criteria for multiple variables as these provided data for more than one study.

Each study or study group was selected to test different attributes of the automated eligibility screening software targeted in the design. We used six specific attributes through which we evaluated the efficiency, flexibility, and generalizibility of the system.

Screening patients based on complex clinical and other eligibility criteria and from multiple data sources.

Capture and screen patients from multiple entry points into the health care system.

Linking both prospective and retrospective clinical information.

Rapid identification and assessment of patients within specified intervals from diagnosis or treatment, or prior to onset of therapy.

Expand the population screened by adding additional data sources from which the patients are selected. Identification and reporting patients who were not routinely accessible to the investigators or research staff.

Performing “generic” automated screening for groups of clinical trials for a particular disease or disease group (i.e. hematologic malignancy Phase I studies or adjuvant breast cancer therapeutic trials).

e. Analysis

Outcomes measured included: the ability of the system to capture appropriate patients (Yield) and the enhancement to efficiency that could be achieved through the automated query. These measures and the overall success of the pilot permitted us to assess the flexibility, generalizibility and efficiency of the system.

i. Calculating Yield for the automated process

Yield was defined as (1- the false positive rate). The false positive rate was defined as the number determined as not eligible on review by research staff divided by the number determined as eligible through the automated screening. The false positive rate was in part impacted by the level of sensitivity requested by the principle investigator or the research coordinator for the study.

ii. Calculating Efficiency

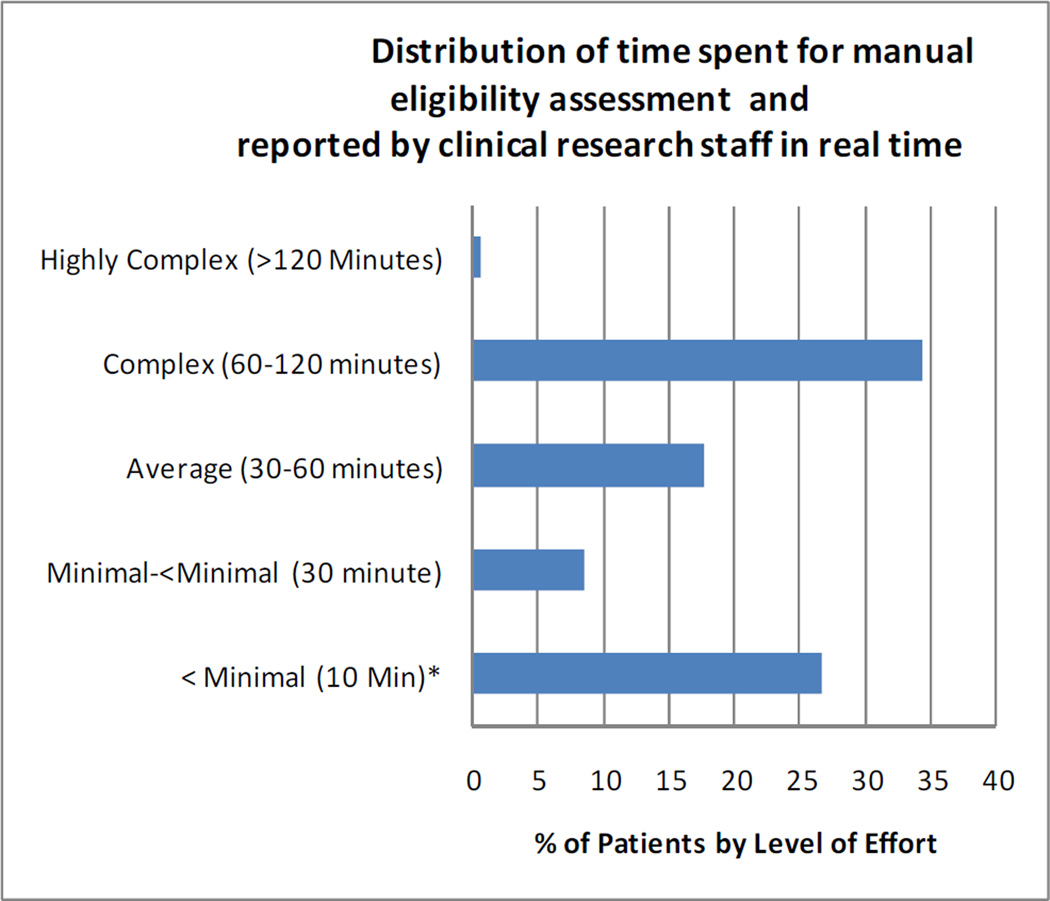

To calculate the efficiency, we compared the time required for manual screening with that for the resulting set of patients identified through the automated process. A component of the existing system captures the level of effort required for each eligibility assessment through a data entry system for research staff. There are five categories of effort in the system as follows: <Minimal (<10 Minutes); Minimal (>10 and < 30 minutes); Average (30–60 minutes); Complex (60–120 minutes ) and Very Complex (>120 minutes). The frequency distribution for effort from 28 months of manual data entry in CTED is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Effort for Eligibility Assessment

iii. Method for attribution of time spent in screening

Attribution of the distribution of time required for screening using the manual method was calculated based on data entered into the system for a 28 month period by the Research Staff (RS). The time captured was that required for manual evaluation of patients. This effort reporting is entered and the level may be modified throughout the process during which eligibility is determined. A patient evaluation record may be modified to express the ongoing level of effort over time.

iv. Calculation of manual effort

For the estimate of the effort required for the manual method, we assumed that the effort distribution for the pilot studies would be the same as that for all studies entered into the system. The distribution of effort for all studies is shown in Figure 2. In addition to the time and effort reported in the system, for evaluating patients on whom there is a scheduled visit, we also included effort related to the additional procedures required for specific trials in this feasibility study.

The calculations for level of effort for studies 1 through 3 included all unique patients in the hospital system scheduling system with a visit during the study interval to the relevant clinic or physicians treating breast cancer, or with a breast cancer diagnosis (ICD-9 174.X).

The additional effort required for Studies 4 and 5 was determined in discussions with the staff performing these tasks and methods for attributing time are described in detail below.

Determination of the effort and number of patients screened for Study 4 differed from that for Studies 1 through 3 as it included effort and time required for screening both inpatient admissions and scheduled visits. Patients screened for these studies included those with scheduled visits for the hematology multi-disciplinary clinic or with physicians specializing in hematologic malignancies or any scheduled patients who had an ICD-9 code indicating a hematologic malignancy (ICD-9 200.X - 208.X). A critical activity in identifying patients for this set of clinical trials is to rapidly evaluate acute inpatient admissions. We therefore included in the estimate for the manual process, the time required for the research nurse to visit the hospital wards daily and speak with the charge nurse or physician. The clinical research nurse responsible for this process reported that these activities took from 45–60 minutes per day. Conservatively we estimated the time and effort based on (45 minutes/day) X (25 week study interval).

The calculations for Study 5 included the time to review patients with scheduled visits to the GI multidisciplinary clinic, to physicians treating colon and rectal cancers or with a diagnosis code for a colon or rectal cancer (ICD-9 153.X-154.X). In addition, because many colorectal cancer patients were identified only through colonoscopic directed biopsy results, we added the time required to manually capture these data and screen the patients. This is a process that is performed daily by the Tissue Acquisition team, who reported that this process required on average 10 minutes per patient screened. The time included 1) searching the outpatient surgical center schedule to identify colonoscopy patients (this must be done manually as it is an independent system), and 2) for patients with colonoscopies, the patient’s record in the EMR was then manually searched to capture and review the patients biopsy results. There are an average of 139 colonoscopic biopsies performed per month (35/week). Attributing 10 minutes per review entails an additional 5.8 hours per week as part of the manual eligibility assessment process for identifying early stage colorectal cancers.

v. Calculation of effort for the automated process

The calculation of effort for the automated process was based on the same distribution of reported effort used for the manual process. However, for the automated process, we assumed that no screening evaluation done on the “pre-screened” patients would require effort of less than 10 minutes. The automated “pre-screening” process performed by the software would likely replace the “<minimal effort” activity required to pre-screen patients and included in the calculations for the manual process. Thus the distribution of effort for subsequent screening of patients identified through the automated system was attributed based on the adjusted distribution of effort using only the “Minimum” or greater categories. That is effort attributed for all patients identified through the automated pre-screening process were attributed as at least 30 minutes of effort for further eligibility determination.

vi. Efficiency comparison

Using the distribution and time/effort allocation calculation described above, we calculated the manual time spent screening patients for each study. We then compared that with the time required for the subset of patients that were “pre-screened” using the automated matching process. The improvement in efficiency (estimated time savings) was determined by directly comparing the effort required for final eligibility determination for patients identified through our automated system with the estimated effort (time) required for the population of patients who would be screened manually. We also calculated a ratio of time per eligible patient identified for the manual versus the automated system.

f. Patient privacy

The data that are included in the integrated system are the same data sources that are utilized by RS to pre-screen patients to evaluate clinical trials eligibility. Access to the system is dictated by approval of the clinical trial by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for Human Subjects Research. The database has undergone independent IRB approval and has been reviewed and received a HIPAA waiver. All data transmissions are performed in a secure encrypted and password protected file to IRB approved research staff and principal investigators.

RESULTS

Yield of the automated process

Table 4 provides an estimate of the number of patients identified as eligible during the study interval through the automated process and the yield (% true positives) after review by research staff. The number of “potentially eligible” patients seen at the cancer center during the study interval and screened through the software ranged from 282 to 2,112 by study. The number of unique patients that were pre-screened as potentially eligible ranged from 65 to 661. These were pre-screened as potentially eligible from the total population based on the eligibility criteria provided in Table 3. Yields ranged from 17.2% to 73.8%. The absolute number of patients identified as eligible for study 1 was the lowest, however the study was included as it represented a trial with moderately stringent clinical criteria including evaluations for specific comorbidities and tumor characteristics. The “false positive” rates, or pre-screened patients who were not truly eligible, ranged from 26.2% to 82.8%. Many of the automatically pre-screened were ultimately ineligible due to factors that were not available in the clinical data sources processed by the automated matching tool. For example patients who had a prior history of cancer diagnosed elsewhere, who were likely to be noncompliant, or who did not speak English were ultimately found to be ineligible.

Table 4.

Yield for automated screening process by study

| Study | Data Collection Interval per Study |

# of Unique Patients Automatically Identified (Pre-screened) as Potentially Eligible |

# of Eligible Patients Confirmed Eligible by CRS |

% False Positive Eligible |

% True Eligible (Yield) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: NSABP B40 Adjuvant Breast Trial | 10 Months | 65 | 48 | 26.2 | 73.8 |

| 2: Incident Breast Cancer among employed, married pre-menopausal women | 30 weeks | 490 | 120 | 75.5 | 24.5 |

| 3: Generic Neoadjuvant Breast Tx | 9 months | 325 | 56 | 82.8 | 17.2 |

| 4: Inpatient Hematologic Malignancies | 25 weeks | 661 | 156 | 76.4 | 23.6 |

| 5: Incident Early Stage Colorectal Cancer | 9 months | 361 | 111 | 69.3 | 30.7 |

Efficiency of the automated system

Table 5 provides the distribution of evaluations and time spent screening patients for the 5 studies and the overall effort for the manual (upper portion of the table) and the automated process (lower portion of the table). The last two columns in Table 5 provide the total number of evaluations and total hours spent in screening for eligibility for each of the studies. For all but Study 5, there was a substantial savings in research staff time in evaluating patients during the study intervals ranging from 165 hours to 1,329 hours.

Table 5.

Time and effort for eligibility evaluation manual versus automated process by study.

| Manual Evaluation Process | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N < Minimal (10 Minutes)* Evaluations |

Time for < Minimal Pts |

N Minimal- <Minimal (30 minute) Evaluations |

Time for < Minimal - <Minimal Pts |

N Average Evaluations |

Time for Average Pts |

N Complex Evaluations |

Time for Complex Pts |

N Highly Complex Evaluations |

Time for Highly Complex Pts |

TOTAL evaluations |

Total Evaluation Time in hours/ Study |

| Study 1 | 352 | 59 | 110 | 37 | 231 | 173 | 455 | 682 | 8 | 16 | 1314 | 967 |

| Study 2 | 184 | 31 | 58 | 19 | 121 | 90 | 237 | 356 | 4 | 8 | 685 | 504 |

| Study 3 | 566 | 94 | 177 | 59 | 372 | 279 | 731 | 1096 | 13 | 25 | 2112 | 1554 |

| Study 4 | 250 | 42 | 78 | 26 | 164 | 123 | 322 | 483 | 6 | 11 | 931 | 685 |

| Study 5 | 66 | 11 | 21 | 7 | 44 | 33 | 86 | 129 | 1 | 3 | 248 | 182 |

| Automated Evaluation Process | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N < Minimal (10 Minutes)* Evaluations |

Time for < Minimal Pts* |

N Minimal- <Minimal (30 minute) Evaluations |

Time for < Minimal - <Minimal Pts |

N Average Evaluations |

Time for Average Pts |

N Complex Evaluations |

Time for Complex Pts |

N Highly Complex Evaluations |

Time for Highly Complex Pts |

TOTAL evaluations |

Total Evaluation Time in hours/ Study |

| Study 1 | 23 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 22 | 34 | 0 | 1 | 65 | 51 | ||

| Study 2 | 41 | 14 | 86 | 65 | 170 | 254 | 3 | 6 | 490 | 339 | ||

| Study 3 | 27 | 9 | 57 | 43 | 112 | 169 | 2 | 4 | 325 | 225 | ||

| Study 4 | 56 | 19 | 116 | 87 | 229 | 343 | 4 | 8 | 661 | 457 | ||

| Study 5 | 30 | 10 | 64 | 48 | 125 | 187 | 2 | 4 | 361 | 249 | ||

No patients identified through automatching were attributed the <minimal time.

Comparing Efficiency of the manual versus automated process

Using the number of eligible patients identified through the automatching process as the calculation basis (column 1 in Table 6), the average number of man hours required to identify an eligible patient was calculated and reported in Table 6. There are considerable time savings for all studies except for Study 5. The ratio of mean time for the manual versus automated patient per eligible patient identified ranges from 0.8 for Study 5 to 19.4 for Study 1.

Table 6.

Comparison of average man hours per eligible patient identified. Manual versus Automated process.

| Eligible Patients |

Manual Hours per eligible patient |

Automated Hours per eligible patient |

Ratio of Manual to Automated Mean Times |

|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | 20.55 | 1.06 | 19.4 |

| 120 | 4.27 | 2.82 | 1.5 |

| 56 | 27.98 | 4.01 | 7.0 |

| 156 | 4.42 | 2.93 | 1.5 |

| 111 | 1.72 | 2.25 | 0.8 |

Discussion

Automated systems for eligibility screening using health information technology tools present a promising solution to the logistical issues facing CRS in identifying and accruing patients to clinical trials [8,16,20–26]. However to date, these tools lack generalizibility as they a) have utilized a customized system against which the queries are run, and b) rely on pre-screening from a few data sources with limited clinical relevance,

Finally, many have been tested against a single clinical trial or for a single disease entity even though a patient may be eligible for a variety of clinical trials over time throughout their disease course [15,24,25,27]. This study of an automated eligibility screening tool evaluated the improvement in efficiency and the flexibility and potential generalizibility of this tool across a variety of clinical trial types.

Efficiency

This study was designed to determine the potential benefit in reducing level of effort to research staff through an automated software system. None of the automated solutions that have been piloted directly measured the benefit to efficiency on eligibility screening [25,35,36]. This is the first study to directly compare an automated versus manual process for clinical trials eligibility screening. The results of this study demonstrate that the amount of time required to identify an eligible patient is significant whether using automation or manual methods. However the automated process greatly reduces that time compared with the traditional manual process by effectively transferring the load of the eligibility assessment process to the computer. This reduction in effort ranged from neutral in one study to nearly a 20 fold decrease in time spent per eligible patient identified. While the study demonstrated time savings for all studies but Study 5, the study was included because no patients were identified for eligibility assessment prior to the initiation of the automatch process. The principal investigator chose to sacrifice efficiency to capture the widest range of possible patients for this study.

Flexibility

In addition to the value in reducing the time research staff spent screening patients, the automated eligibility screening software demonstrates flexibility. It was successful in improving efficiency and in capturing patients across a wide variety of clinical trial scenarios. These studies ranged from traditional therapeutic cancer trials to broader screening tools for rapidly identifying patients either within a short interval of diagnosis or prior to the onset of therapy- both critical requirements for many clinical trials [37].

The system tested in this study was designed to directly address many of the barriers to screening patients in a timely and accurate manner. These barriers included complexity of clinical trial eligibility requirements, complexity of health care systems and data sources, requirement for rapid identification of patients, and varied entry route of patients into the health care system. The approach of using a variety of trials for which determination of eligibility is impacted by these barriers allowed a wider validation space for our system compared to the studies previously reported in the literature [16,20–28].

Specific examples demonstrating the flexibility of the system are as follows. In Studies 2 and 5 the system was able to identify newly diagnosed cancer patients within a short interval from the time of diagnosis, and who entered the health care system through a variety of pathways. For Study 4, the automated process was sufficiently flexible to provide a solution to two problems faced by CRS. It reduced the time required for screening, and more importantly permitted clinical research staff to quickly identify potentially eligible and newly diagnosed patients with hematologic malignancies. These patients were otherwise often identified subsequent to the initiation of treatment and automatically ineligible for CTs. Automated daily hospital census processing successfully provided a list of relevant patients within 24 hours of admission. Prior to the automated system, clinical research staff were required to visit each hospital floor and ward to which oncology patients might be admitted on a daily basis, or to depend on notification of new patient admissions from the attending physicians. Because of the significant time commitment for this manual process (approximately 45–60 minutes per day) the research nurse was frequently unable to leave the cancer center to perform this task. Thus potentially eligible patients were missed.

The flexibility of the system is further demonstrated in the success in pre-screening patients across multiple studies simultaneously as was done for Study 3. Research staff for breast cancer adjuvant treatment trials developed a grid which was used to manually evaluate patients in the breast multidisciplinary clinic. The software prospectively provided a list of pre-screened patients (Table 1) who could be reviewed for eligibility in more than one study by research staff prior to their scheduled appointment.

Although the efficiency of the process was slightly less for the manual process than for the automated process (1.72 hours versus 2.25 hours) for study 5, the automated system nevertheless provided another opportunity to directly address a challenge faced by research coordinators for this study. Prior to the implementation of the automatching process, no patient accruals occurred to the study. Few patients were identified through the multi-disciplinary clinic because patients in this clinic were often either late stage or recurrent disease and thus not eligible. Further, once early stage patients were scheduled, the 30 day window for enrollment had frequently passed. The initiation of the automated screening utilizing the colonoscopy schedule and surgical pathology reports provided near real-time identification of patients with early stage disease. These patients were diagnosed via colonoscopy by noncancer specialists (gastroenterologists). A proportion of these patients diagnosed through gastroenterology subsequently received their treatment at other facilities, thus would never have been identified without the expanded criteria to include non cancer center patients.

The use of the automated eligibility assessment permits the CRS to assess patient eligibility using a wider range of eligibility parameters than they could efficiently perform using manual methods. As a result, the researcher is able to perform more accurate and complete eligibility assessments. In fact that capacity is in part reflected in the variation in false positive rates across the studies. The false positive rate was determined by the research staff according to the need to have the highest sensitivity to identify all cases at the sacrifice of a lower specificity and higher false positive rate. The higher rate of false positives for studies in this pilot reflects the need for rapid identification of the largest population of potential patients (sensitivity) balanced against maintaining a high specificity. For Studies 2, 4 and 5, the automated matching process and identification of eligible patients represented a unique tool to identify patients on whom information was not otherwise readily available.

Generalizibility

Many of the systems described in the literature provide similar capabilities in terms of data searching, and use of Natural Language Processing (NLP) for assessing data repositories for clinical trials eligibility assessment [25,35,36]. However, one of the unique features of this tool is that we based its searching function on commonly available and/or standardized electronic data sources that are likely to permit this system to be implemented in other health care entities. The use of universally available billing data as a key component of the initial pre-screening process to reduce the population to be screened via NLP is a unique feature that contributes to the ability to transfer this system to other health care entities. While HL7 messages are not standard per se, they are commonly available from the two other critical data sources utilized by this tool: surgical pathology and clinical pathology reports [28]. While having an eligibility screening tool that is integrated with the Electronic Health record (EHR) is likely to ultimately be the most efficient system for pre-screening patients for clinical trial eligibility. Currently only 1.5% of health care systems have a fully implemented EHR [28]. Thus until an interoperable and more standardized clinical data warehouse becomes available the capacity to transport individually designed and developed tools for automated assessment of clinical trials eligibility is limited. EHRs are not currently capable of addressing all documentation needs for clinical trials [37]. Despite the lack of interoperability and full implementation, the same study found that >75% of hospital systems do have operational electronic systems for radiology and pathology laboratories results reporting.[28] Thus using these key clinical data components for automated assessment is likely to have significantly greater generalizibility [28].

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, in order to capture time required for evaluating all potentially eligible patients, we estimated based on retrospective data entered into an existing system at the time of the eligibility evaluation. Historically the system was not in use across all research areas, thus the direct level of effort per patient determined to be eligible was not directly measurable but was based on a sample of 4,315 eligibility evaluation records in the database. Further, the manual system does not provide a comprehensive estimate of the effort in screening patients as it is not possible to assure that each patient is screened. Thus we based our estimates on an ideal system in which every patient was evaluated for the studies included in our pilot. This limitation further supports the potential benefit of the automated system. Because of the limited time resources of the research staff potentially eligible patients may be missed and not offered the opportunity to participate. Thus automation of this process assures that every patient will be screened. This assurance that all patients are evaluated is the first critical step in reducing the disparities in clinical trials enrollment [14]. A third limitation of the system is that the yield for many of the studies included is relatively low. This is in part due to the thresholds set by the CRS and principal investigators. However, the automated screener serves as a “pre-screening” tool that a) identifies potentially eligible patients who are otherwise not easily captured for further evaluation or b) quickly and efficiently eliminates patients who do not meet many of the eligibility criteria. There will always be further manual review required, as complete clinical information necessary to assess eligibility may not be available within the electronic data sources. For example, a patient may have been treated at an outside facility and the information is only available in hard copy or via telephone contact. Thus, while the system can likely achieve a higher yield than for some of the studies included in the manuscript, we anticipate that there will always be a significant number of false positives until data are available for integration from across health care systems.

Conclusion

Automation offers an opportunity to reduce the burden of the manual processes and to assure that all patients have an opportunity to be evaluated for participation in clinical trials as appropriate. The system detailed in this paper provides data to support the value of automation in this screening process. Because the system automatically pre-screens all patients, it means that every patient has an equal opportunity to be evaluated and to participate in clinical trials [38,39]. We believe that increased eligibility screening will ultimately result in increasing the number of participants in clinical trials [14]. The system significantly reduces time requirements to perform pre-screening of all patients by automating the process and providing a subset of likely eligible patients to the clinical research staff. The system is flexible, permitting the inclusion of a broad range of study types, and offers direct solutions to barriers identified by research staff in rapid and timely identification of potentially eligible patients. The system is generalizible, using commonly available and/or standardized data sources. While the system was designed for generalizibility to both a broad range of clinical trials and to other cancer centers through its use of commonly available and “standardized” electronic data sources, further evaluation must be done. Implementation of the system on a wider scale and prospectively measuring the impact on clinical trials accrual will determine the true benefit.

Acknowledgments

Statement of Funding: This project was supported by the Massey Cancer Center.

Development an testing of the software application used in this project was approved by the VCU IRB #HM11089

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ellis P, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN, Dunn SM. Accrual to clinical trials in breast cancer. Annual Scientific Meeting of the Clinical Oncological Society of Australia; Brisbane, Australia. 1996. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lara PN, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, Kwan K, Tanaka M, Lau DH, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(6):1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avis NE, Smith KW, Link CI, Hortobagyi GN, Rivera N. Factors associated with participation in breast cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(12):1860–1867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolata G. Forty years' war: lack of study volunteers hobbles cancer fight. New York Times; 2009. Aug 3, [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winn RJ. Obstacles to the accrual of patients to clinical trials in the community setting. Semin Oncol. 1994;21(4 suppl 7):112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald AM, Knight RC, et al. What Influences recruitment to randomized controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials. 2006;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eastbrook PJ, Mathews DR. Fate of research studies. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:71–76. doi: 10.1177/014107689208500206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks L, Power E. Using technology to address recruitment issues in the clinical trial process. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20(3):105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01881-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson JM, Trochim WMK. An examination of community members', researchers’ and heath professionals’ perceptions of barriers to minority participation in medical research: An application of concept mapping. Ethn Health. 2007;12(5):521–539. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Quirt G, et al. Lessons learned from enrollment in the BEST study – a multi-center randomized trial of group psychosocial support in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peelen L, Peek N, et al. The use of registry database in clinical trial design: Assessing the influence of entry criteria on statistical power and number of eligible patients. Intl. J. of Med. Inf. 2007;76:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanco C, Olfson M, Goodwin RD, et al. Generalizibility of clinical trial results for major depression to community samples. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):1276–1280. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albrecht TL, Eggly SS, Gleason ME, Harper FW, Foster TS, Peterson AM, et al. Influence of clinical communication on patients' decision making on participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2666–2673. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dugas M, Lange M, Berdel WE, Müller-Tidow C. Workflow to improve patient recruitment for clinical trials within hospital information systems – a case-study. Trials. 2008;9:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fink E, Kokku PK, Nikiforou S, Hall LO, Goldgof DB, Krischer JP. Selection of patients for clinical trials: an interactive web-based system. Artif Intell Med. 2004;31(3):241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afrin LB, Kuppuswamy V, Slatter B, Stuart RK. Electronic clinical trial protocol distribution via the world-wide web: a prototype for reducing costs and errors, improving accrual and saving trees. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(1):25–35. doi: 10.1093/jamia/4.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell EG, Weissman JS, Moy E, Blumenthal D. Status of clinical research in academic research centers. JAMA. 2001;286(7):800–806. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.7.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung NS, Crowley WF, Jr, Genel M, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289(10):1278–1287. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butte AJ, Weinstein DA, Kohane IS. Enrolling patients into clinical trials faster using Real Time Recruiting. Proc AMIA Symp. 2000:11–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiner DL, Butte AJ, Hibberd PL, Fleisher GR. Computerized recruiting for clinical trials in real time. Ann Emerg Med Feb. 2003;41(2):242–246. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Embi PJ, Jain A, Clark J, Bizjack S, Hornung RW, Harris CM. Effect of a clinical trial alert system on physician participation in trial recruitment. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(19):2272–2277. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.19.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding J, Erdal S, Borlawsky T, Liu J, Golden-Kreutz D, Kamal J, Payne PR. The design of a preencounter clinical trial screening tool: ASAP. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008 Nov 6;:931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borlawsky T, Payne PR. Evaluating an NLP-based approach to modeling computable clinical trial eligibility criteria. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007 Oct 11;:878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamal J, Pasuparthi K, Rogers P, Buskirk J, Mekhjian H. Using an information warehouse to screen patients for clinical trials: a prototype. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gennari JH, Sklar D, Silva J. Cross-tool communication: from protocol authoring to eligibility determination. Proc AMIA Symp. 2001:199–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vahabzadeh M, Lin JL, Mezghanni M, Contoreggi C, Leff M. A clinical recruiting management system for complex multi-site clinical trials using qualification decision support systems. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007 Oct 11;:1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Donelan K, Rao SR, Ferris TG, Shields A, Rosenbaum S, Blumenthal D. Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 16;360(16):1628–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0900592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren JL, Harlan LC, Fahey A, et al. Utility of the SEER-Medicare data to identify chemotherapy use. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-55–IV-61. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020944.17670.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamont EB, Herndon t JE, 2nd, Weeks JC, et al. Criterion validity of Medicare chemotherapy claims in cancer and leukemia group B breast and lung cancer trial participants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(14):1080–1083. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamont EB, Lauderdale DS, Schilsky RL, Christakis NA. Construct validity of Medicare chemotherapy claims: The case of 5FU. Med Care. 2002;40(3):201–211. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du XL, Key CR, Dickie L, Darling R, Geraci JM, Zhang D. External validation of Medicare claims for breast cancer chemotherapy compared with medical chart reviews. Med Care. 2006;44(2):124–131. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196978.34283.a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClish DK, Penberthy L, Whittemore M, et al. Ability of Medicare claims data and cancer registries to identify cancer cases and treatment. Am J Epi. 1997;145(3):227–233. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penberthy L, McClish D, Pugh A, Smith W, Manning C, Retchin S. Using hospital discharge files to enhance cancer surveillance. Am J Epi. 2003;158(1):27–34. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fink E, Kokku PK, Nikiforou S, Hall LO, Goldgof DB, Krischer JP. Selection of patients for clinical trials: an interactive web-based system. Artif Intell Med. 2004 Jul;31(3):241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ash N, Ogunyemi O, Zeng Q, Ohno-Machado L. Finding appropriate clinical trials: evaluating encoded eligibility criteria with incomplete data. Proc AMIA Symp. 2001:27–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pressler S, Subramanian U, et al. Research in Patients with Heart Failure: Challenges in Recruitment. Amer. J. of Critical Care. 2008;Vol. 17(No. 3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;115(2):228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Go RS, Frisby KA, Lee JA, et al. Clinical trial accrual among new cancer patients at a communitybased cancer center. Cancer. 2006;106(2):426–433. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]