Abstract

Background and purpose:

We have previously shown that SB265610 (1-(2-bromo-phenyl)-3-(7-cyano-3H-benzotriazol-4-yl)-urea) behaves as an allosteric, inverse agonist at the C-X-C chemokine (CXCR)2 receptor. The aim of this study was to determine whether SB265610, in addition to two other known antagonists, bind to either of the two putative, topographically distinct, allosteric binding sites previously reported in the Literature.

Experimental approach:

Ten single point mutations were introduced into the CXCR2 receptor using site-directed mutagenesis. Three CXCR2 antagonists were investigated, SB265610, Pteridone-1 (2-(2,3 difluoro-benzylsulphanyl)-4-((R)-2-hydroxy-1-methyl-ethylamino)-8H-pteridin-7-one) and Sch527123 (2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[(R)-1-(5-methyl-furan-2-yl)-propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxo-cyclobut-1enylamino}-benzamide), and the effect of these mutations on their binding affinity and ability to inhibit interleukin-8-stimulated binding of [35S]GTPγS was examined.

Key results:

Seven of the nine mutations introduced into the C-terminal domain and intracellular loops of the receptor produced a significant reduction in affinity at least one of the antagonists tested. Of those seven mutations, three produced a significant reduction in the affinity of all three antagonists, namely K320A, Y314A and D84N. In all but one mutation, the changes observed on antagonist affinity were matched with effects on inhibition of interleukin-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding.

Conclusions and implications:

These antagonists bind to a common intracellular, allosteric, binding site of the CXCR2 receptor, which has been further delineated. As many of these mutations are close to the site of G protein coupling or to a region of the receptor that is responsible for the transduction of the activation signal, our results suggest a molecular mechanism for the inhibition of receptor activation.

Keywords: CXCR2 receptor, allosteric, SB265610, site-directed mutagenesis, homology modelling, Sch527123, mechanism of action

Introduction

The C-X-C chemokine (CXCR)2 receptor (nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2008) is a G protein-coupled receptor that is expressed on many different inflammatory and structural cells, regulating pulmonary functions. It is not surprising therefore that CXCR2 has been implicated in the pathology in a variety of lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cystic and pulmonary fibrosis (see Chapman et al., 2009). This growing body of evidence, indicating that CXCR2 plays an important role in pulmonary disease, has lead to several pharmaceutical companies identifying potent and selective CXCR2 antagonists, many of which have now advanced into clinical trials. The outcome of these trials will determine the fate of CXCR2 antagonists that at present hold considerable promise for the treatment of a wide range of acute and chronic pulmonary disorders.

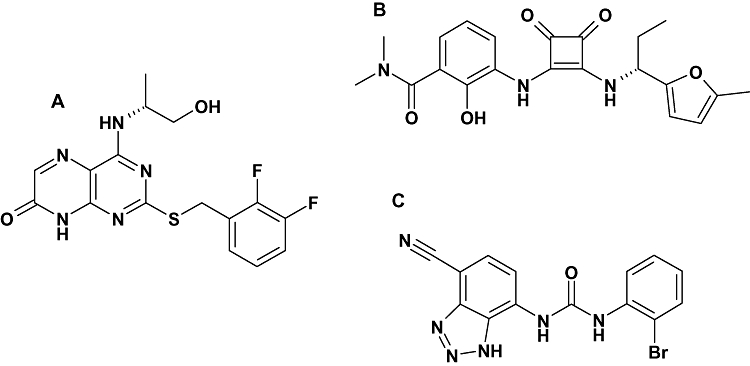

We have previously shown that SB265610 (1-(2-bromo-phenyl)-3-(7-cyano-3H-benzotriazol-4-yl)-urea) (Figure 1C) behaves as an allosteric, inverse agonist at the CXCR2 receptor (Bradley et al., 2009). Specifically we showed that SB265610 exhibits elements of an inverse agonist that stabilizes the inactive conformation of the CXCR2 receptor. It does not compete directly with the agonist, but rather binds to an allosteric region to prevent receptor activation, without directly affecting agonist affinity. The molecular mechanism of such antagonism at the receptor level has not been adequately described to date. One possibility is that the binding site of SB265610 is located close to the site of G protein coupling or to a region of the receptor critically involved in the transduction of the activation signal following agonist binding.

Figure 1.

Structures of the C-X-C chemokine (CXCR)2 antagonists studied. (A) Pteridone-1 (2-(2,3 difluoro-benzylsulphanyl)-4-((R)-2-hydroxy-1-methyl-ethylamino)-8H-pteridin-7-one), (B) Sch527123 (2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[(R)-1-(5-methyl-furan-2-yl)-propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxo-cyclobut-1enylamino}-benzamide) and (C) SB265610 (1-(2-bromo-phenyl)-3-(7-cyano-3H-benzotriazol-4-yl)-urea).

To date, two putative antagonist allosteric binding sites have been reported for the CXCR2 receptor. The first of these sites derived from studies with Repertaxin and the CXCR1 receptor, which shares 77% sequence homology with CXCR2 (Bertini et al., 2004). In this study, a combination of receptor modelling and mutagenesis of the CXCR1 receptor identified a site within the transmembrane regions (TM) of the receptor, specifically residues in TM1, 2, 3, 6 and 7. Repertaxin is also claimed to inhibit the CXCR2 receptor but with lower potency. In a subsequent study to design novel inhibitors with comparable potency at CXCR1 and CXCR2, the putative allosteric TM binding pocket of CXCR2 was obtained by molecular modelling techniques using data from the mutagenesis of CXCR1 (Moriconi et al., 2007). From this, a number of residues in the TM region of CXCR2 were identified, specifically E300 in TM7, which is comparable to E291 in CXCR1. This glutamate residue in TM7 is one of a number of residues that have been identified as part of a common allosteric binding pocket in the TM region of a number of CC and CXCR receptors (Allegretti et al., 2008; Carter and Tebben, 2009). The second, and less well documented, putative allosteric binding site is on the intracellular side of the receptor in the C-terminal domain (Nicholls et al., 2008). This study utilized C-terminal domain exchange with CXCR1 with limited single point mutagenesis, although a key lysine reside at position 320 on the C-terminal tail of TM7 was identified. This intracellular allosteric site has also been identified in other chemokine receptors, namely CCR4 and 5 (Andrews et al., 2008).

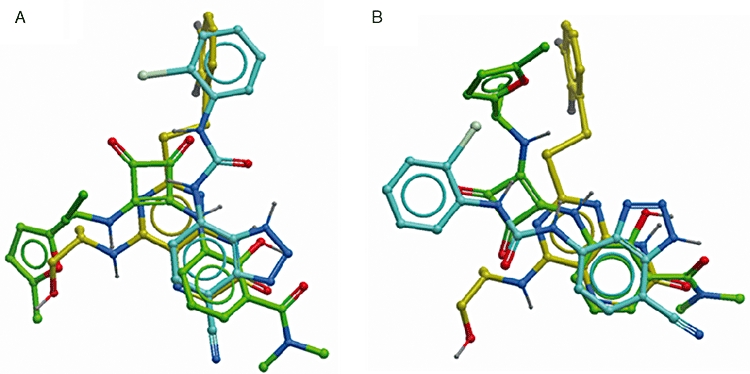

Although it is quite possible for more than one allosteric antagonist binding site to exist within a receptor, as has been described for muscarinic receptors (Birdsall and Lazareno, 2005), the two sites proposed for the CXCR2 receptor are topographically distinct and it would not be possible for a single, low molecular weight, antagonist to contact residues at both sites simultaneously. Consequently, one of the main aims of this study was to determine whether the allosteric binding site of SB265610 could be identified as one of the sites already proposed (Moriconi et al., 2007; Nicholls et al., 2008). In addition, two other CXCR2 antagonists were investigated; Sch527123 (2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[(R)-1-(5-methyl-furan-2-yl)-propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxo-cyclobut-1enylamino}-benzamide) (Figure 1B) has been reported to be a potent allosteric CXCR1/CXCR2 antagonist (Gonsiorek et al., 2007) and 2-(2,3 difluoro-benzylsulphanyl)-4-((R)-2-hydroxy-1-methyl-ethylamino)-8H-pteridin-7-one (Figure 1A) represented as example 44 in patent application WO/2001/062758 (Bonnert et al., 2001) and is termed Pteridone-1 in this study. Pteridone-1 is from the same chemical class exemplified by compound A, which was used in the study by Nicholls et al. (2008). In-house studies have shown that, as with SB265610, both Pteridone-1 and the squaramide (Sch527123) behave as allosteric inverse agonists (data not shown). Small molecule-derived overlays have shown that, although the three antagonists are from different chemical series, they share similar chemical features such as an acidic centre and possibly a hydrophobic side chain or hydrogen-bonding core/side chain combination (Figure 2A). Therefore, the second aim of this study was to determine whether each of these antagonists share the same allosteric binding site.

Figure 2.

Small molecule overlay of SB265610 (1-(2-bromo-phenyl)-3-(7-cyano-3H-benzotriazol-4-yl)-urea) (blue), Sch527123 (2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[(R)-1-(5-methyl-furan-2-yl)-propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxo-cyclobut-1enylamino}-benzamide) (green) and Pteridone-1 (2-(2,3 difluoro-benzylsulphanyl)-4-((R)-2-hydroxy-1-methyl-ethylamino)-8H-pteridin-7-one) (yellow). (A) Predicted overlay before results of mutagenesis study; (B) overlay using results from mutagenesis study.

In order to investigate this, 10 single point mutations were introduced into the CXCR2 receptor using site-directed mutagenesis. The effect of these mutations on antagonist affinity and ability to inhibit interleukin (IL)-8-stimulated binding of [35S]GTPγS has not only enabled us to confirm that these antagonists bind to a common intracellular site in the CXCR2 receptor, but it has also allowed for further delineation of this intracellular allosteric binding pocket.

Methods

Generation of hCXCR2 construct

Human CXCR2 (hCXCR2) cDNA (GENBANK:L19593) was amplified by PCR using a 5′ primer containing an EcoR I cleavage site and a 3′ primer containing a Not I site. The PCR product was ligated into a pXOON plasmid vector and the product transformed into Top10 competent Escherichia coli cells. The transformation protocol was as follows: 30 min on ice, then heat shocked for 30–45 s at 42°C, cooled on ice for a further 2 min, incubated at 37°C for 1 h with gentle agitation and then grown at 37°C on LB agar plates (supplemented with 0.01 mg·mL−1 kanamycin), overnight. Following this, colonies were picked and inoculated in LB broth for approximately 16 h to increase the yield of plasmid DNA, which was isolated and purified using both the QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (5 mL inoculation) and HiSpeed Plasmid Maxiprep kit (50 mL inoculation). The purified DNA was sequenced on both strands of the CXCR2 insert.

Generation of point mutations

Point mutations were created using the QuickChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, DNA primers were designed containing a single- or double-base substitution resulting in a codon change for the desired amino acid substitution. These primers and their complements were synthesized (Sigma) and then used to generate mutant plasmids by PCR using the wild-type pXOON hCXCR2 construct and PfuUltra™ DNA polymerase. Methylated or hemimethylated non-mutated plasmid DNA was removed by Dpn I digestion. The products were transformed into Top10 E. coli competent cells, as detailed above, and the CXCR2 coding region was sequenced to verify that the correct mutation had been introduced.

Cell culture and transfection

Prior to transfection Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-Trex cells were maintained in CHO-K1 media [Ham's F12 supplemented with l-glutamine, 10% (v·v−1) EU heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin G (100 U·mL−1)/streptomycin sulphate (100 µg·mL−1)]. At 40% confluency, CHO-Trex cells cultured in 75 cm2 cell culture flasks were transfected using Optimem Media and FuGENE 06 at a 3:1 ratio with plasmid DNA. After 24 h, selection of transfectants was carried out by supplementing the CHO-K1 media with 0.5 mg·mL−1 geneticin. Subsequently, cells were maintained in CHO-K1 media containing 0.5 mg·mL−1 geneticin to generate a stable pool of cells expressing the receptor.

Generation of stable cell lines expressing wild-type and mutated CXCR2 receptor

Stable pools of cells expressing wild-type and mutated CXCR2 receptors were grown to 80% confluency, washed with phosphate-buffered saline and detached from the flask using enzyme-free cell dissociation buffer. The cells were then resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer [phosphate-buffered saline with Ca2+Mg2+, 0.1% (w·v−1) BSA] and incubated on ice with the allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated mouse anti-human CXCR2 antibody (1 in 2.5 dilution of antibody) in the dark, for 20 min, after which they were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer. Single cell sorting was carried out using the MoFlo cell sorter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and cells were selected based on level of cell surface binding of APC anti-CXCR2 antibody. Cells were initially sorted into 96-well plates and grown into stable cell lines using geneticin-enriched CHO-K1 media.

Cell surface receptor expression using flow cytometry

Transfected CHO-Trex cells stably expressing wild-type and mutated CXCR2 receptors and untransfected CHO-Trex cells were washed and detached from the flask according to the method described above. Cells were incubated on ice for 30 min, with either APC-conjugated mouse anti-human CXCR2 antibody or the corresponding APC-conjugated mouse IgG isotype control. Following washing and resuspension in FACS buffer, cell surface receptor expression was analysed by flow cytometry. FACS analysis was performed with the FACScaliber MAC4 (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer using CellQuest software.

Preparation of membranes from CHO cells stably expressing wild-type or mutated CXCR2 receptor

Chinese hamster ovary cells stably expressing wild-type and mutated CXCR2 receptor were grown to 90% confluency in 500 cm2 cell culture trays. Cells were harvested in ice-cold HEPES-buffered saline/EDTA [10 mM HEPES, 0.9% (w·v−1) NaCl, 0.2% (w·v−1) EDTA, pH 7.4]. All of the subsequent steps were carried out at 0–4°C. A cell pellet was recovered by centrifugation (15 000×g for 5 min), and the pellet was homogenized using a Polytron homogenizer (5 × 5 s bursts) in buffer 1 (10 mM HEPES, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). The homogenate was centrifuged (48 000×g for 30 min) and the pellet re-homogenized and centrifuged as described above. The final pellet was suspended in buffer 2 (10 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) at a concentration of 5–7 mg of protein·mL−1 and stored at −80°C.

Equilibrium radioligand binding studies

Binding assays were carried out with the CXCR2 receptor agonist [125I]IL-8 and the CXCR2 receptor antagonists [3H]SB265610, [3H]Pteridone-1 and [3H]Sch527123. All experiments were at room temperature (∼21°C) in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4) and 0.01 % (w/v) human serum albumin (HSA). Binding was initiated by the addition of CHO-CXCR2 membranes (wild-type or mutated receptor); the incubation period was 2 h for [125I]IL-8, [3H]SB265610 and [3H]Pteridone-1 and 72 h for [3H]Sch527123. All experiments were terminated by vacuum filtration (96-well manual harvester – PerkinElmer) onto polyethylenimine (PEI)-treated GF/C plates for [125I]IL-8 and non-PEI treated GF/B plates for [3H]-antagonists. The filter plates were washed three times with ice-cold wash buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) and oven-dried prior to the addition of scintillation fluid (Microscint-20). The amount of radioactivity on each filter was detected using a Topcount Scintillation counter (PerkinElmer).

Two different methods were used to determine radioligand affinity (Kd) and receptor expression (Bmax). The first of these and the more traditional method was saturation binding, whereby a range of concentrations of radioligand were incubated with cell membranes in the absence (total binding) and presence (non-specific binding) of a saturating concentration of unlabelled ligand. Specific binding was defined as the difference between total and non-specific binding and when plotted against radioligand concentration (linear scale) yields a one-site hyperbola, generating a Kd and Bmax value for the radioligand (equation 1). The second method employed was homologous binding, in this case only two concentrations of radioligand were incubated with a range of concentrations of the same ligand but non-radiolabelled. This method yields two sigmoidal concentration effect curves, which when analysed using equation (2) produce a Kd and Bmax value for the radioligand.

[35S]GTPγS binding assay

[35S]GTPγS binding to CHO-CXCR2 membranes was measured using scintillation proximity assay (SPA). All experiments were run at room temperature (∼21°C) in the same buffer as used for radioligand binding [20 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4) and 0.01 % (w·v−1) HSA] but with 10 µg·mL−1 saponin added. CHO-CXCR2 membranes (wild-type or mutated receptor) (10 µg) were incubated with 0.1 µM GDP, 0.5 mg per well wheat germ agglutinin SPA beads and IL-8 (EC50 concentration) in the presence and absence of a range of concentrations of SB265610 or Pteridone-1, for 60 min. This initial pre-incubation was performed to allow the agonist and antagonist to equilibrate prior to the addition of [35S]GTPγS (0.3 nM), which was followed by a further 60 min incubation. The assay plates were centrifuged prior to detection of [35S]GTPγS binding using a Topcount scintillation counter.

Receptor modelling

The TM domains of the receptor were modelled using the backbone coordinates of bovine rhodopsin from PDB ref. 1F88 and an in-house alignment tool. The missing intracellular loop regions were modelled using the loop search procedure within the SYBYL modelling suite (TRIPOS Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA; http://www.tripos.com), which produces a given number of possible loops (by default 25) for each loop sequence. These loops were ranked by homology to the CXCR2 loop sequence and RMS fit of the termini to the TM domain termini and the most satisfactory one for each loop was chosen by visual inspection. The extracellular loops were modelled in a similar fashion purely for completeness. Steric and electrostatic clashes introduced by modelling the CXCR2 sequence onto the bovine rhodopsin backbone were removed by a combination of manual side chain rotations and constrained minimizations where the backbone, side chains, C-α atoms were independently fixed to allow relaxation but minimize disturbance of the overall structure (RMS gradient for convergence set at levels 1, 0.5 and finally 0.05 kcal·mol−1 using the MMFF94 forcefield, dielectric 1.0, non-bonded cut-off 8 Ångstrom.)

The small molecule overlays that had been previously generated in-house were used in a manual docking process that positioned the acidic centre close to the lysine 320 in the model; the hydrophobic benzyl thioether side chain of Pteridone-1 was orientated such that it was buried in the TM helices and this arrangement defined the positioning of the other compounds. Potential mutations were then selected based upon their proximity to these various ligands and their ability to help determine the validity of this area and the proposed binding modes of the three series.

Calculations and data analysis

Analysis was performed using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Saturation binding isotherms were analysed by non-linear regression according to a hyperbolic, one-site binding model, and individual estimates for total receptor number (Bmax) and radioligand dissociation constant (Kd) were calculated. The following equation was used, where [A*] is the concentration of radioligand:

|

(1) |

Estimates for total receptor number (Bmax) and radioligand dissociation constant (Kd) from homologous binding were calculated using the equation shown below:

|

(2) |

Where [A*] is the concentration of radioligand, [A] is the concentration of non-radiolabelled ligand, and NS is non-specific binding. [35S]GTPγS binding assays was analysed by non-linear regression, sigmoidal dose–response (variable slope) according to the following equation:

|

(3) |

Where Y is the amount of radioligand bound (cpm) or % of specific binding, Top denotes maximal asymptotic binding, and Bottom denotes the minimal asymptotic binding.

All results are presented as mean ± SEM unless stated and were calculated from separate experiments, where n represents the number of experiments performed.

Materials

Human recombinant [125I]IL-8 (specific activity 2200 Ci·mmol−1), [35S]GTPγS (specific activity 1250 Ci·mmol−1) and Microscint-20 scintillation fluid were purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA, USA). [3H]Pteridone-1, [3H]SB265610 and [3H]Sch527123 were prepared in-house by Pharma DMPK – Isotope Laboratories (Basle, Switzerland). Recombinant human IL-8, Pteridone-1, SB265610 and Sch527123 were prepared in-house. CHO-Trex cells and all cell culture reagents, including Top10 E. coli competent cells, were purchased from Invitrogen (Paisley, UK). pXOON plasmid vector obtained from the University of Copenhagen (Jespersen et al., 2002). FuGENE 06 transfection reagent, PfuUltra™ DNA polymerase, T4 DNA ligase and restriction endonucleases were purchased from Roche (Burgess Hill, UK). Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Sigma. QuickChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit was purchased from Stratagene (Amsterdam, the Netherlands). QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit and HighSpeed Maxiprep kit were purchased from Qiagen (Crawley, UK). Wheat germ agglutinin-coupled SPA beads were purchased from GE Healthcare (Chalfont St Giles, UK). APC-conjugated mouse anti-human CXCR2 (CD128b) and APC-conjugated mouse isotype control IgG antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Ninety-six-well GF/B and GF/C filter plates were purchased from Millipore (Watford, UK). White 96-well Optiplates were from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Boston, MA, USA). Tris-HCl, MgCl2, EDTA, HEPES, NaCl, HSA, saponin and GDP were purchased from SigmaChemical Co. Ltd. (Poole, UK).

Results

Characterization of wild-type CXCR2 receptor expressed in CHO cells

In order to ensure that the procedures for cloning, transformation and transfection of mutated receptors would produce functionally active CXCR2 receptors, wild-type CXCR2 was cloned into CHO-Trex cells and characterized. Both IL-8 and growth-related oncogene (GRO)α stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding with the same efficacy, producing mean pEC50 values of 8.47 ± 0.06 (n= 7) and 8.35 ± 0.12 (n= 6) respectively. The Kd value for [125I]IL-8 from saturation binding and homologous binding studies was determined to be 0.143 ± 0.031 (n= 5) and 0.122 ± 0.040 nM (n= 4) respectively. In addition, the Bmax value for [125I]IL-8 from saturation binding and homologous binding studies was determined to be 0.257 ± 0.060 and 0.368 ± 0.076 pmol·mg−1 protein respectively. These data show that the homologous binding method produces Kd and Bmax values that are comparable to data from saturation binding studies. In addition, the values obtained from both function and binding studies were comparable to those determined from CHO cells expressing CXCR2 receptors, purchased from Euroscreen (Brussels, Belgium) (Bradley et al., 2009) and confirmed that the wild-type CXCR2 receptor has been successfully cloned into CHO-Trex cells in this study.

Successful generation of 10 stable cell lines expressing single-point mutation of CXCR2 receptor

Ten site-directed single point mutations were introduced into the CXCR2 receptor, as listed in Table 1. Wild-type residues were mutated such that they would alter the size, electrostatic properties, hydrogen bonding network and hydrophobicity to give an indication of the properties and residues playing a significant role in the binding of the antagonists at the CXCR2 receptor. Transfection of CHO-Trex cells with pXOON vectors containing the desired mutations in the CXCR2 sequence, and subsequent selection for transformants using a geneticin-enriched cell culture medium, resulted in a pool of CHO cells stably expressing the mutated CXCR2 receptor. All of the mutated receptors that were made were shown to be expressed at the cell surface using APC-labelled anti-CXCR2 and FACS (data not shown). Single cell sorting was then performed to create clonal cell lines. The aim was to closely match receptor expression of each of the receptor mutations to that of the wild-type receptor to achieve a comparable level of receptor reserve between cell lines. However, in practice this was very difficult to achieve without screening a large number of clones therefore only two clones per receptor mutant (medium and high receptor expression) were tested and the one with receptor expression, which most closely matched that of the wild-type receptor, was selected. In some cases, the mutated receptor cell lines exhibited expression comparable to the wild type (within threefold), except for K320A, E300Q, F321A and T83L with five-, eight-, seven- and sixfold higher receptor expression respectively.

Table 1.

Mutations introduced into the wild-type CXCR2 receptor

| Mutation | Amino acid position | Wild-type residue | Mutated residue | Reason for mutation | Nomenclature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 320 | Lysine | Alanine | Disrupts ion pair interaction between the residue and the compound | K320A |

| 2 | 314 | Tyrosine | Alanine | Destabilizes pocket | Y314A |

| 3 | 249 | Alanine | Leucine | Occludes binding site | A249L |

| 4 | 300 | Glutamate | Glutamine | Key residue in transmembrane binding site reported by Moriconi et al. (2007) | E300Q |

| 5 | 321 | Phenylalanine | Alanine | Disrupts hydrophobicity of binding pocket | F321A |

| 6 | 84 | Aspartate | Asparagine | Disrupts ion pair with adjacent K320 | D84N |

| 7 | 83 | Threonine | Alanine | Limits hydrogen bonding network in enlarged pocket | T83A |

| 8 | 147 | Alanine | Leucine | Occludes binding site and introduces hydrophobicity | A147L |

| 9 | 83 | Threonine | Leucine | Occludes binding site and limits polar interactions | T83L |

| 10 | 143 | Aspartate | Arginine | Change in charge | D143R |

CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor.

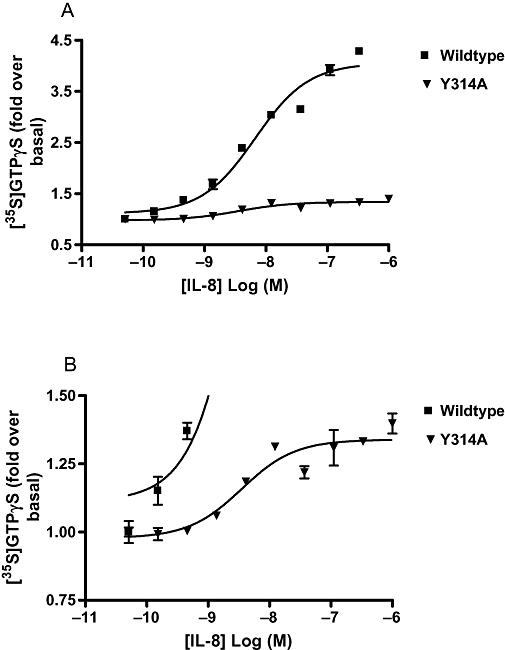

Effect of mutations in the CXCR2 receptor on the potency and affinity of IL-8

The affinity of [125I]IL-8 was determined for each of the mutants (Table 2). Unfortunately, low receptor expression in the A147L cell line (twofold less than wild type) made it difficult to obtain significant levels of specific binding and only two saturation binding isotherms could be obtained. However, for all of the mutations, the Kd obtained for [125I]IL-8 was within threefold of wild type, which suggests that none of the mutations affected IL-8 affinity. IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding assays were carried out to establish whether any of the mutations had adversely affected the function of the receptor. Table 2 shows pEC50 values obtained for IL-8 in each of the receptor-mutated cell lines. As can be seen, all of the mutated receptors except A147L showed IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding, giving pEC50 values comparable to the wild-type receptor, indicating that receptor function was retained in these mutants. Interestingly, the response seen with Y314A compared with that of the wild type was very small but very reproducible with a pEC50 value for IL-8 comparable to wild type (Figure 3). Despite attempts to try and match receptor expression across all cell lines, some of the mutated receptors showed fivefold or greater receptor expression levels compared with the wild-type receptor. Consequently, a higher receptor reserve in the mutated cell lines may have masked possible effects of the mutations on the potency of IL-8.

Table 2.

Effect of CXCR2 receptor mutations on pEC50 and Kd values for IL-8

| Mutation | Kd (nM) | Fold-shift | pEC50 | Fold-shift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 0.134 ± 0.019 (9) | 8.47 ± 0.06 (7) | ||

| K320A | 0.358 ± 0.017 (3) | 2.7 | 8.21 ± 0.03 (4) | 1.7 |

| Y314A | 0.289 ± 0.068 (4) | 2.2 | 8.23 ± 0.19 (3) | 1.8 |

| A249L | 0.321 ± 0.093 (4) | 2.5 | 8.05 ± 0.06 (4) | 2.5 |

| E300Q | 0.238 ± 0.026 (3) | 1.8 | 8.14 ± 0.04 (4) | 2.0 |

| F321A | 0.211 ± 0.056 (3) | 1.6 | 8.91 ± 0.12 (4) | 0.4 |

| D84N | 0.211 ± 0.075 (3) | 1.6 | 8.49 ± 0.12 (4) | 1.0 |

| T83A | 0.232 ± 0.020 (3) | 1.7 | 8.39 ± 0.12 (4) | 1.3 |

| A147L | 0.193 ± 0.021* (2) | 1.4 | No response | |

| T83L | 0.270 ± 0.040 (3) | 2.0 | 8.14 ± 0.05 (3) | 2.0 |

| D143R | 0.149 ± 0.015 (4) | 1.1 | 8.13 ± 0.04 (3) | 2.1 |

Data shown are mean ± SEM, n given in parentheses.

Data represents mean ± range as it has been calculated from only two experiments. Kd values have been determined using both saturation and homologous binding.

CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor; IL, interleukin.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of interleukin (IL)-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in wild-type and Y314A mutated C-X-C chemokine (CXCR)2 receptor cell membranes. (A) Data pictured on graph using full scale y-axis. (B) Same data as in (A) but pictured on graph showing only lower part of y-axis to highlight the presence of a curve with the Y314A mutated CXCR2 receptor. Data shown are representative of at least three separate experiments. Data points are mean of duplicate determinations ± range.

Effect of mutations in the CXCR2 receptor on antagonist inhibition and affinity

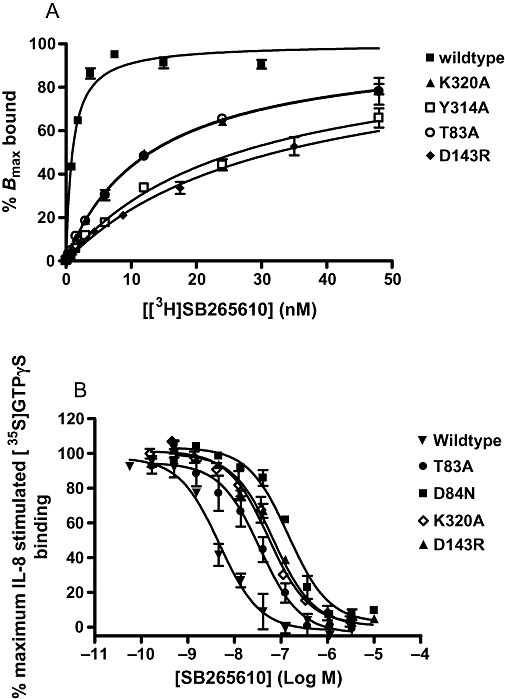

SB265610

The affinity of [3H]SB265610 was unaltered by the mutations E300Q, T83L, A249L and F321A (Table 3), in addition, it was possible to determine the affinity of [3H]SB265610 at the A147L mutation, and this was unchanged when compared with wild-type. In contrast, the binding of [3H]SB265610 was completely abolished by the D84N mutation and markedly reduced by the mutations D143R (12-fold), T83A (sixfold) and K320A (fivefold), as shown in Figure 4A. Finally, it was possible to detect binding of [3H]SB265610 to the Y314A mutant, and this showed an almost ninefold reduction in the affinity of this antagonist, when compared with the wild-type receptor. pIC50 values were determined for SB265610 in an IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding assay. In order to compare the values obtained between the different mutations, equi-effective (EC50) concentrations of IL-8 were used, although as there was no functional response to IL-8 in the A147L mutant and a very small response in the Y314A mutant, pIC50 values could not be determined for these mutations. Mean pIC50 values are shown in Table 4; E300Q, T83L, A249L and F321A produced little effect on the IC50 of SB265610 (within threefold) when compared with wild type. In contrast, the mutations D84N, D143R, K320A and T83A produced 27-, 12-, 9- and 7-fold reductions in IC50 respectively (Figure 4B). In all cases, changes in the affinity of SB265610 compared well with changes in the ability of the antagonist to inhibit IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding.

Table 3.

Kd values for [3H]SB265610, [3H]Pteridone-1 and [3H]Sch527123 determined from both saturation and homologous binding experiments in CHO membranes expressing wild-type and mutated CXCR2 receptor

| Kd (nM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]SB265610 | Fold-shift | [3H]Pteridone-1 | Fold-shift | [3H]Sch527123 | Fold-shift | |

| Wild-type | 2.10 ± 0.38 (9) | 2.37 ± 0.28 (7) | 0.059 ± 0.008 (5) | |||

| K320A | 9.34 ± 1.83 (3) | 4.5 | 38.77 ± 10.68 (3) | 16.4 | 1.82 ± 0.39 (3) | 30.8 |

| Y314A | 18.33 ± 3.91 (3) | 8.7 | No binding detected | 0.415 ± 0.097 (3) | 7.0 | |

| A249L | 3.54 ± 0.81 (4) | 1.7 | 33.64 ± 3.75 (3) | 14.2 | 16.52 ± 0.915 (3) | 280.1 |

| E300Q | 2.88 ± 0.50 (4) | 1.4 | 3.43 ± 0.86 (3) | 1.4 | 0.032 ± 0.019 (3) | 0.5 |

| F321A | 3.96 ± 1.22 (4) | 1.9 | 5.41 ± 1.06 (4) | 2.3 | 0.109 ± 0.051 (3) | 1.8 |

| D84N | No binding detected | 10.79 ± 2.96 (4) | 4.6 | 4.10 ± 2.23 (3) | 69.5 | |

| T83A | 11.65 ± 2.16 (3) | 5.6 | 3.54 ± 1.21 (3) | 1.5 | 0.694 ± 0.234 (3) | 11.8 |

| A147L | 3.24 ± 0.68 (3) | 1.5 | 1.85 ± 0.19 (3) | 0.8 | 0.194 ± 0.026 (3) | 3.3 |

| T83L | 1.89 ± 0.21 (3) | 0.9 | 0.93 ± 0.07 (3) | 0.4 | 2.47 ± 0.78 (3) | 41.9 |

| D143R | 25.38 ± 3.85 (4) | 12.1 | 2.56 ± 0.21 (3) | 1.1 | 0.804 ± 0.351 (3) | 13.6 |

Data shown are mean ± SEM, n given in parentheses.

CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor; Pteridone-1, 2-(2,3 difluoro-benzylsulphanyl)-4-((R)-2-hydroxy-1-methyl-ethylamino)-8H-pteridin-7-one; SB265610, 1-(2-bromo-phenyl)-3-(7-cyano-3H-benzotriazol-4-yl)-urea; Sch527123, 2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[(R)-1-(5-methyl-furan-2-yl)-propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxo-cyclobut-1enylamino}-benzamide.

Figure 4.

Effects of C-X-C chemokine (CXCR)2 receptor mutations on SB265610 (1-(2-bromo-phenyl)-3-(7-cyano-3H-benzotriazol-4-yl)-urea) affinity. (A) Kd values determined from saturation binding and (B) inhibition of interleukin (IL)-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding. Saturation binding data are representative of three separate experiments; data points are mean of triplicate determinations ± SEM. IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding data are mean ± SEM of at least three separate experiments.

Table 4.

pIC50 values for SB265610 and Pteridone-1 determined from IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in CHO membranes expressing wild-type and mutated CXCR2 receptor

|

pIC50 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB265610 | Fold-shift | Pteridone-1 | Fold-shift | |

| Wild-type | 8.31 ± 0.09 (9) | 7.63 ± 0.09 (9) | ||

| K320A | 7.30 ± 0.13 (4) | 9.5 | 6.54 ± 0.05 (3) | 10.5 |

| Y314A | ND | ND | ||

| A249L | 8.44 ± 0.20 (3) | 0.7 | 6.54 ± 0.05 (3) | 10.3 |

| E300Q | 8.32 ± 0.10 (4) | 0.9 | 7.64 ± 0.06 (3) | 0.8 |

| F321A | 7.87 ± 0.06 (4) | 2.3 | 6.29 ± 0.01 (3) | 23.1 |

| D84N | 6.79 ± 0.04 (3) | 27.3 | 6.63 ± 0.05 (3) | 8.4 |

| T83A | 7.39 ± 0.04 (3) | 6.9 | 7.22 ± 0.14 (3) | 2.4 |

| A147L | ND | ND | ||

| T83L | 8.31 ± 0.06 (3) | 0.8 | 7.88 ± 0.13 (3) | 0.5 |

| D143R | 7.16 ± 0.06 (4) | 11.9 | 7.39 ± 0.03 (4) | 1.4 |

Data shown are mean ± SEM, n given in parentheses.

CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor; IL, interleukin; ND, not determined; Pteridone-1, 2-(2,3 difluoro-benzylsulphanyl)-4-((R)-2-hydroxy-1-methyl-ethylamino)-8H-pteridin-7-one; SB265610, 1-(2-bromo-phenyl)-3-(7-cyano-3H-benzotriazol-4-yl)-urea.

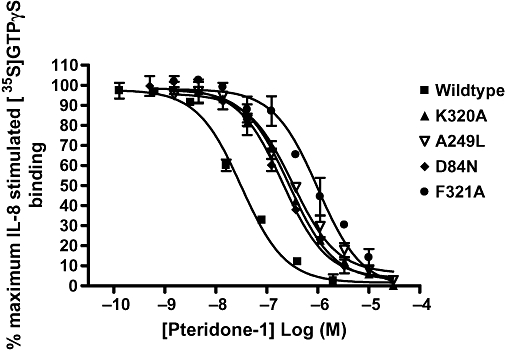

Pteridone-1

As described for SB265610, Kd values using [3H]Pteridone-1 and pIC50 values from IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding assay were determined for this antagonist. The results of direct affinity measurements using [3H]Pteridone-1 are summarized in Table 3 and show that no changes in antagonist affinity were observed for E300Q, T83A, T83L and D143R. In addition, it was possible to obtain binding data for A147L, which showed that the affinity of [3H]Pteridone-1 was unaltered by this mutation. In contrast, the binding of [3H]Pteridone-1 was completely abolished in the Y314A mutant and reduced 16-, 14- and 5-fold in the K320A, A249L and D84N mutants respectively. pIC50 values determined for Pteridone-1 are shown in Table 4. Receptor mutants E300Q, T83A, T83L and D143R produced little effect on the IC50 (within threefold) when compared with wild type. In contrast, the receptor mutants K320A, A249L, D84N and F321A all produced a reduction in the IC50 of Pteridone-1, with F321A causing the greatest shift (23-fold), followed by K320A and A249L (both 10-fold) and D84N (eightfold) (Table 4, Figure 5). Correlations between the effects observed on affinity and IL-8 inhibition are good for all of the receptor mutants, apart from F321A that did not show any effect on [3H]Pteridone-1 affinity (twofold) but produced a 23-fold reduction in its IC50 value, when compared with wild type.

Figure 5.

Pteridone-1 (2-(2,3 difluoro-benzylsulphanyl)-4-((R)-2-hydroxy-1-methyl-ethylamino)-8H-pteridin-7-one) inhibition of interleukin (IL)-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in Chinese hamster ovary cell membranes expressing wild-type or mutated C-X-C chemokine (CXCR)2 receptors. Data shown are representative of at least three separate experiments. Data points are mean of duplicate determinations ± range.

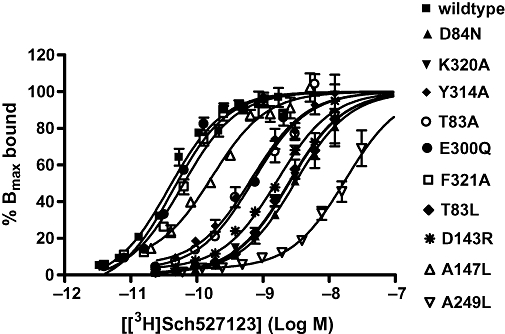

Sch527123

Sch527123 dissociates very slowly from the receptor ((t1/2∼ 22 h –Gonsiorek et al., 2007), and the relatively short incubation time (2 h) of the [35S]GTPγS binding assay would not allow for complete equilibration of this antagonist. It was deemed inappropriate to use this assay to investigate the effects of the mutations on Sch527123. Consequently, only the affinity of [3H]Sch527123 was determined for each of the mutations. Table 3 shows that E300Q, F321A and A147L have little effect on [3H]Sch527123 binding affinity (within threefold). However, all of the other mutations significantly reduced the affinity of [3H]Sch527123 for the CXCR2 receptor as shown in Figure 6. The greatest effect was observed with the A249L mutation, which showed a 280-fold loss in affinity. Following that, D84N, T83L and K320A produced 69-, 41- and 30-fold reductions in [3H]Sch527123 affinity respectively. Finally, D143R, T83A and Y314A showed lesser effects on affinity of 13-, 11- and 7-fold respectively.

Figure 6.

Kd deteminations for [3H]Sch527123 in Chinese hamster ovary cell membranes expressing wild-type and or CXCR2 receptors. Data shown are representative of at least three separate experiments. Data points are mean of triplicate determinations ± SEM, and the top of each curve has been fixed to 100%. CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor; Sch527123, 2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[(R)-1-(5-methyl-furan-2-yl)-propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxo-cyclobut-1enylamino}-benzamide.

Discussion

In this study, a total of 10 site-directed point mutations were introduced into the CXCR2 receptor. Nine of the mutations were targeted to the putative allosteric intracellular binding site as described by Nicholls et al. (2008) and one to a putative allosteric binding site in the TM region of the receptor, reported by Moriconi et al. (2007). Three CXCR2 antagonists were investigated, SB265610, Pteridone-1 and Sch527123, and the effect of these mutations on binding affinity and ability to inhibit IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS was examined. The mutations were chosen to test the validity of the intracellular binding site and the proposed binding modes of the three antagonists, as implied by the small molecule-based overlays generated in-house.

Stable cell lines were generated for each mutation and were all shown to be expressing the mutated receptor at the cell surface. The affinity of the endogenous agonist IL-8 for the mutated receptors was shown to be unchanged when compared with wild type, indicating that the conformation of the receptor at the level of agonist binding had not been altered by any of the mutations. With the exception of the A147L mutation and in part Y314A, all of the other mutations produced IL-8-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding, with EC50 values comparable to the wild-type receptor. The absence of receptor function exhibited by the A147L mutation and the reduction in receptor function exhibited by the Y314A mutation could not be attributed to lack of receptor expression, suggesting that these two residues may play a role in the transduction of the signal, following agonist binding or directly affect G protein coupling. A147 has not been directly implicated in G protein coupling; however, it is one helical turn below arginine 144 that forms part of the highly conserved DRY motif and that has been shown to be a trigger in G protein coupling (Nygaard et al., 2009; Rovati et al., 2007). Y314 is the highly conserved tyrosine in the NPXXY motif found in the seventh TM domain of most G protein-coupled receptors. This motif has long been assumed to be an internalization sequence (Hausdorff et al., 1991); however, it has been shown to regulate both internalization and receptor signalling. In the chemotactic formyl peptide receptor, mutation of the asparagine residue (N297A) completely abolished receptor signalling and internalization (He et al., 2001). In addition, in line with our observations, mutation of the tyrosine residue to alanine showed a reduced chemotactic response compared with wild type, even though it responded better to lower concentrations of N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (FMLF). In the bradykinin B2 receptor, mutation of the tyrosine to alanine (Y305A) in the conserved NPXXY sequence produced constitutive phosphorylation and internalization, but the receptor was not able to signal (Kalatskaya et al., 2004). It was concluded that Y305 in the bradykinin B2 receptor plays an important role in keeping the receptor in an inactive uncoupled state. We have shown that Y314 in the NPXXY motif of CXCR2 receptor may also appear to play a critical role in receptor signalling.

The mutation of glutamate to glutamine at position 300 (E300Q) was the only mutation targeted to the TM region of the receptor. This residue has been implicated in CXCR2 antagonist binding from modelling studies performed by Moriconi et al. (2007). As this putative allosteric binding site is topographically distinct from the site proposed by Nicholls et al. (2008), it would be impossible for one small molecule antagonist to bind to both sites simultaneously. The lack of effect we observed with the E300Q mutation, with all three antagonists, in combination with significant effects of mutations at the intracellular regions of the receptor, suggest that the antagonists tested in this study do not bind to the putative TM allosteric binding site proposed by Moriconi et al. (2007).

Three mutations introduced into the C-terminal tail of TM7 and the intracellular loop 1 showed a significant reduction in affinity of all three antagonists; these were K320A, Y314A and D84N. Nicholls et al. (2008) mutated K320 to asparagine that conferred a different ionization state at physiological pH. This mutation produced approximately a 10-fold reduction in affinity of the two antagonists tested in that study. In our study this residue was mutated to alanine to disrupt any ionic interaction between the lysine and the acidic group present on each of the antagonists. The reduction in affinity observed for each antagonist with this mutation confirms the importance of this residue, as reported by Nicholls et al. (2008). In addition, if the magnitude of the fold-shift in affinity for a mutation corresponds to the importance of that residue for antagonist binding, then the greatest effect of this mutation was observed with Sch527123 with least effect observed with SB265610.

For Y314, our hypothesis was that this residue may form part of the hydrophobic stacking region, supporting the putative binding pocket and as a consequence, mutating this residue to alanine would destabilize the binding pocket. The affinity of all three antagonists was reduced, with comparable effects on SB265610 and Sch527123 and more significant effects on Pteridone-1, as no specific binding could be detected at the concentrations tested.

The final mutation that affected the affinity of all three antagonists was a mutation of the aspartate at position 84 to asparagine. The model predicts that this mutation would disrupt the ion pairing with the adjacent K320 residue. This mutation had significant effects on both SB265610 (no binding detected) and Sch527123 and lesser effects on Pteridone-1. Taking only these data into account it is possible to conclude these three antagonists share a common binding site located on the intracellular side of the CXCR2 receptor.

However, although there are some residues that either directly or indirectly affect the affinity of all three antagonists, there are also a number of residues that are specific to two of the antagonists (A249L, T83A and D143R) or in some cases, only one of the antagonists (T83L). One of the most interesting of these mutations was D143R. This residue is the D in the highly conserved DRY motif that has been connected with G protein coupling (Nygaard et al., 2009). The E/DRY motif is at the intracellular pole of TM3; the arginine residue (R) is the most conserved residue among G protein-coupled receptors and has been known to be involved in receptor signalling for many years (Rovati et al., 2007). Novel X-ray structures show that in the inactive receptor conformation, R144 makes a salt bridge to neighbouring E/D143 (E/DRY motif) and it is very likely that protonation of E/D143 is an integral part of the G protein receptor activation mechanism. In the active structure of opsin, this arginine residue is rotated away from glutamate to instead make a hydrogen bond interaction with the highly conserved tyrosine residue. In this new, stabilized position between TM3, 5 and 6, the guanidino group of the arginine forms the top of the binding pocket for the Gα peptide (Nygaard et al., 2009).

The antagonists we have studied prevent receptor activation without affecting agonist binding affinity, and it was postulated that the molecular mechanism of such antagonism may be that the binding site of the antagonists is close to the site of G protein coupling or to a region of the receptor that is responsible for the transduction of the activation signal following agonist binding. Our results have shown that this might well be the case, given that the binding of two of the antagonists tested in this study was affected by mutation in the DRY motif of the receptor and the binding of all three antagonists was affected by a mutation in the NPXXY motif. Moreover, almost all of the residues that were mutated are located at the very ends of the TM regions, bordering the intracellular loops that are known to make contact with the G protein.

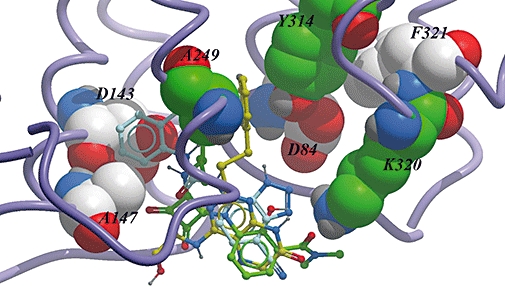

The small molecule-derived overlays showed that some features were consistent between series, the acidic centre and possibly a hydrophobic side chain or the H-bonding core/side chain combination (Figure 2A). Prior to obtaining the mutation data, the positioning of these overlays within the receptor model was simply a matter of positioning the acidic centre close to the basic K320 side chain and the hydrophobic side chain directed into the TM domain that in turn directed the more H-bonding side chains towards the intracellular aqueous space. From these positionings one would have expected similar effects of the mutations on Pteridone-1 and SB265610 with the Sch527123 squaramide being more dissimilar; however, the data did not confirm this. For example, the A249L mutation affected Pteridone-1 and Sch527123 and not SB265610. In this case it was predicted that the occlusion of the site by the larger residue would prevent binding of the hydrophobic groups within both Pteridone-1 and SB265610 and not the squaramide, which did not occupy that area in the small molecule overlay. While there were some consistent effects with respect to the K320A, Y314A and D84N mutations (although the magnitude differed across the compounds) many of the mutations had different effects on the different series, which brings into question the validity of the small molecule overlays. Based on the mutation data, the compound overlays have been modified (Figure 2B) and positioned in the binding site (Figure 7). The acidic centres are still relatively well overlaid, but the hydrophobic group of the urea side chain of SB265610 is placed more towards TM3, 4 and 5 in order to explain the more significant effects that the mutations in this region have on the urea series, relative to Pteridone-1. In addition, the triazole of SB265610 has been brought closer to D84. The A249L mutation would suggest that the furan side chain of Sch527123 should be directed into the TM domain rather than mimicking the alcohol chain of Pteridone-1. It is interesting to note the similarity between the effects of the mutants on Sch527123 and SB265610, as the squaramide could be viewed as a urea mimic. However even here differences in the effect of the T83L mutation on these two antagonists demonstrate significantly different binding modes between the two series. Finally, if the binding site is intracellular, it suggests that these antagonists diffuse across the cell membrane. The partition coefficient (logD) between octanol and aqueous solution at pH 6.8 was calculated to be greater than 2.5 for all three antagonists. The correlation between lipophilicity and antagonist potency in a cell-based system was investigated by Nicholls et al. (2008) and compounds with lower lipophilicity showed a weak but significant trend towards reduced antagonism in a cellular system compared with a cell-free system. In addition, cell permeability determined using a Caco-2 cell system (Artursson and Tavelin, 2003) was shown to be passive transcellular for all three antagonists used in this study.

Figure 7.

Intracellular binding pocket of the C-X-C chemokine (CXCR)2 receptor showing the binding modes of three different antagonists based on the results from this mutagenesis study.

To date, the majority of mutation studies involving chemokine receptors have identified a small molecule antagonist binding site within the TM region of the receptor, capped by extracellular loop 2 and frequently possessing a critical contact with a conserved glutamic acid residue located in TM7 (Carter and Tebben, 2009). An additional allosteric site was subsequently identified deeper inside the receptor bundle, bounded on one side by the intracellular C-terminal domain (Andrews et al., 2008; Nicholls et al., 2008). However, in the main, the identification of this deeper site was performed using C-terminal domain swapping and although Nicholls et al. identified K320 as an important residue in the CXCR2 receptor, further delineation of the binding pocket has not been performed until now. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that mutations in the C-terminus could cause slight changes in the conformation that could reduce the binding affinity of these molecules to the TM region, it is our belief that these three CXCR2 antagonists from different chemical series bind within the intracellular C-terminal domain of the receptor. In addition, they display different binding modes, which were not apparent from small molecule overlays. Finally, these data confirm the presence of an allosteric binding site close to the site of G protein coupling or to a region of the receptor that is responsible for the transduction of the activation signal and, thus, suggest a molecular mechanism for inhibition of receptor activation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank James Neef and Hansjoerg Lehmann for synthesizing the compounds and the DMPK Isoptope laboratories in Basle for synthesizing the radioligands. We would also like to thank Romain Wolfe for the use of his G protein-coupled receptor factory tool that deals with the sequence alignment and initial TM domain model building and Paul Groot-Kormelink for his molecular biology expertise.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- CXCR

C-X-C chemokine receptor

- GRO

growth-related oncogene

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- SB265610

1-(2-bromo-phenyl)-3-(7-cyano-3H-benzotriazol-4-yl)-urea

- Sch527123

2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[(R)-1-(5-methyl-furan-2-yl)-propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxo-cyclobut-1enylamino}-benzamide

- SPA

scintillation proximity assay

- TM

transmembrane

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 2):S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allegretti M, Bertini R, Bizzarri C, Beccari A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Allosteric inhibitors of chemoattractant receptors: opportunities and pitfalls. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(6):280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Jones C, Wreggett KA. An intracellular allosteric site for a specific class of antagonists of the CC chemokine G protein-coupled receptors CCR4 and CCR5. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73(3):855–867. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artursson P, Tavelin S. Caco-2 and emerging alternatives for prediction of intestinal drug transport: a general overview. In: van de Waterbeemd H, Lennernäs H, Artursson P, editors. Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry. München, Germany: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. pp. 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bertini R, Allegretti M, Bizzarri C, Moriconi A, Locati M, Zampella G, et al. Noncompetitive allosteric inhibitors of the inflammatory chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2: prevention of reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11791–11796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402090101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall NJ, Lazareno S. Allosterism at muscarinic receptors: ligands and mechanisms. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5(6):523–543. doi: 10.2174/1389557054023251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnert R, Gardiner S, Hunt F, Walters I. Pteridine compounds for the treatment of Psoriasis. 2001. Patent application WO/2001/062758.

- Bradley ME, Bond ME, Manini J, Brown Z, Charlton SJ. SB265610 is an allosteric, inverse agonist at the human CXCR2 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:328–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PH, Tebben AJ. Chapter 12. The use of receptor homology modeling to facilitate the design of selective chemokine receptor antagonists. Methods Enzymol. 2009;461:249–279. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RW, Phillips JE, Hipkin RW, Curran AK, Lundell D, Fine JS. CXCR2 antagonists for the treatment of pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121(1):55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsiorek W, Fan X, Hesk D, Fossetta J, Qiu H, Jakway J, et al. Pharmacological characterization of Sch527123, a potent allosteric CXCR1/CXCR2 antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:477–485. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff WP, Campbell PT, Ostrowski J, Yu SS, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. A small region of the beta-adrenergic receptor is selectively involved in its rapid regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(8):2979–2983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R, Browning DD, Ye RD. Differential roles of the NPXXY motif in formyl peptide receptor signalling. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):4099–4105. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen T, Grunnet M, Angelo K, Klaerke DA, Olesen SP. Dual-function vector for protein expression in both mammalian cells and Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biotechniques. 2002;32(3):536–538. doi: 10.2144/02323st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalatskaya I, Schüssler S, Blaukat A, Müller-Esterl W, Jochum M, Proud D, et al. Mutation of tyrosine in the conserved NPXXY sequence leads to constitutive phosphorylation and internalization, but not signaling, of the human B2 bradykinin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(30):31268–31276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriconi A, Cesta MC, Cervellera MN, Aramini A, Coniglio S, Colagioia S, et al. Design of noncompetitive interleukin-8 inhibitors acting on CXCR1 and CXCR2. J Med Chem. 2007;50(17):3984–4002. doi: 10.1021/jm061469t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DJ, Tomkinson NP, Wiley KE, Brammall A, Bowers L, Grahames C, et al. Identification of a putative intracellular allosteric antagonist binding-site in the CXC chemokine receptors 1 and 2. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74(5):1193–1202. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard R, Frimurer TM, Holst B, Rosenkilde MM, Schwartz TW. Ligand binding and micro-switches in 7TM receptor structures. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30(5):249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovati GE, Capra V, Neubig RR. The highly conserved DRY motif of class A G protein-coupled receptors: beyond the ground state. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(4):959–964. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]