Abstract

Animal models of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) are highly desired to enable detailed investigation of the pathogenesis of these diseases. Multiple rats and mice have been generated in which a mutation similar to that occurring in TSC patients is present in an allele of Tsc1 or Tsc2. Unfortunately, these mice do not develop pathologic lesions that match those seen in LAM or TSC. However, these Tsc rodent models have been useful in confirming the two-hit model of tumor development in TSC, and in providing systems in which therapeutic trials (e.g., rapamycin) can be performed. In addition, conditional alleles of both Tsc1 and Tsc2 have provided the opportunity to target loss of these genes to specific tissues and organs, to probe the in vivo function of these genes, and attempt to generate better models. Efforts to generate an authentic LAM model are impeded by a lack of understanding of the cell of origin of this process. However, ongoing studies provide hope that such a model will be generated in the coming years.

Introduction

Animal models are well-known as invaluable tools in the understanding of human disease. They provide the ability to investigate disease development in ways that are not possible in humans. Mice of the appropriate genotype may be sacrificed at the time chosen by the scientist, with rapid and complete collection of all important tissues and fluids. Animal models are ideal (and in many cases mandatory) for the testing of possible therapeutic interventions, of all kinds, so-called preclinical testing. Animal model studies in lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) have been pursued with considerable vigor. Nonetheless, there is no animal model that comes close to replicating the pathology and pathophysiology of either LAM or the related pathologic lesion, angiomyolipoma (AML).

Early studies on TSC models were accelerated by the fortuitous discovery of a spontaneous rat model of Tsc2 mutation (the Eker rat, see below), and focused on analysis of tumors and their pathology and development. More recent work, over the past 11 years, has focused on development of mouse models of TSC, using genetic engineering. Mouse models have the advantage that there is a large and ever-expanding collection of other mutant alleles available, which can be used for genetic interaction analysis in vivo. In addition, conditional alleles in the mouse permit targeted loss of the gene in tissues of interest.

In this article, I review the various rodent models of TSC that have been developed, particularly those that have pathological findings in the kidneys and lungs, organs significantly affected in LAM and TSC.

The Eker Rat

The Eker rat was first described as an autosomal dominant, hereditary model of predisposition to renal adenoma and carcinoma in 1954 by Reidar Eker.1 Decades later, these animals came to the attention of Alfred Knudson,2,3 who recognized their value and led a series of pathologic and genetic studies, which culminated in the recognition that the underlying genetic defect was a spontaneous mutation in the Tsc2 gene.

In the Eker rat, genotype Tsc2Ek/+, cystadenoma lesions in the kidney are the predominant pathologic lesion, and vary in morphology from pure cysts, to cysts with papillary projections, to solid adenomas,4 which can be seen as early as 4 months of age. A small minority of these tumors become malignant, with nuclear atypia, and expansion to replace the entire kidney and occasional metastasis to the lungs, pancreas, and liver. Although there is strain variance in severity (see below), there is 100% penetrance of kidney involvement in Eker rats. The kidney tumors develop in the outer cortex and have variable staining characteristics, even within a single cystadenoma.4 Three-dimensional reconstruction studies demonstrate that these lesions grow through the kidney by extending along the tubule of origin with localized regions of cystic expansion with or without papillary growth.4 Although these tumors occur in an organ that is commonly involved by angiomyolipoma (AML) in both TSC and LAM patients, these cystadenomas are epithelial neoplasms, and there is no pathological relationship between AML and cystadenomas. Renal cysts are present in a substantial fraction of TSC patients, though are most severe in those with combined deletion of both TSC2 and PKD1. However, in patients without that combined deletion syndrome, they typically remain small and asymptomatic, and do not progress with papillary growth. Thus, renal cysts in TSC patients have a distinct biologic behavior that contrasts with what is seen in the Eker rat.

Eker rats also develop pituitary adenomas (55% at 2 years), uterine leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas (47%–62% of females at 14 months–2 years), and splenic hemangiosarcomas (23%–68% at 14 months– 2 years).2,5

Genetic linkage studies in the Eker rat, followed by identification of TSC2 in the syntenic region of linkage led to the identification of the Eker mutation in Tsc2.3,6 It is an insertion of a 6.3 kb intracisternal A particle into Tsc2 that likely occurred as a spontaneous transposon insertional mutagenesis event. The insertion disrupts codon 1272 of rat Tsc2 and is predicted to lead to production of an aberrant, larger protein, which has never been detected,7 likely due to its poor stability and rapid clearance.

The Eker rat has provided strong evidence that the Tsc2 gene functions in a tumor suppressor gene fashion, fitting the classic Knudson model. In that model, germline inactivation of Tsc2 in the Eker allele is complemented by second-hit loss of the other, wild-type allele in tumors. This second-hit event is postulated to be the critical initiating event leading to tumor formation. This model is supported by analysis of lesions developing in the Eker rat, which have shown consistent loss of the wild-type (Tsc2+) allele. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH), consistent with a second-hit deletion of Tsc2+, is seen in 40%–60% of renal adenomas, 36% of uterine leiomyomas, and 35% of pituitary adenomas.8,9 In contrast, 0% of splenic hemangiomas show this finding, possibly related to admixture of normal cell types.8 Further analysis has shown that about one-third of both spontaneous and ENU-induced renal adenomas in the Eker rat are due to small mutations in the Tsc2 gene.10,11

The ultimate proof of the two-hit model of pathogenesis in the Eker rat was obtained by Hino and colleagues.12 They generated a transgenic rat bearing an additional copy of the wild-type rat Tsc2 gene and its upstream promoter element. The transgene completely compensated for the Tsc2Ek allele in a dosage-dependent manner.

Eker rats develop uterine leiomyomas at high frequency, and these tumors have been studied in detail by Walker and colleagues.13 LOH for Tsc2 and loss of Tsc2 expression are seen in most tumors, oophorectomy is highly effective at leiomyoma suppression, and pregnancy also reduces tumor incidence.14 However, TSC patients do not appear to be at increased risk of uterine leiomyomas, though this should be studied in greater detail, and human uterine tumors show no direct evidence of involvement of the TSC genes.13

The size of kidney tumors that develop in the Eker rat vary as a function of strain, even though the number of tumors does not vary significantly.15 Using a backcross analysis between two strains that showed a substantial difference in tumor size, a quantitative trait locus, Mot1, influencing tumor size was localized to rat chromosome 3q.15

All stages of the renal tumors developing in the Eker rat have been shown to express markers of mTORC1 activation, including phospho-S6(S235-236) and phospho-p70S6K(T389),16 consistent with the critical role of Tsc2 in the regulation of rheb-GTP levels and mTORC1 activation, and in accordance with the two-hit model of tumor development. In addition, these expression features are eliminated and proliferation, as assessed by PCNA staining, is markedly reduced in response to short-term treatment with rapamycin.16 Serial ultrasound imaging has also been used in the Eker rat model to track the size of kidney cystadenomas during treatment.17 The majority of lesions showed a dramatic decrease in estimated tumor volume (46%–98%), with histologic confirmation of ‘tumor scars', fibrotic lesions with few viable tumor cells, in the treated rats. However, there were also other tumors that seemed unaffected by rapamycin therapy.17 Note as well that in this study, pituitary tumors were found to be the major cause of death. Rapamycin was also found to be highly effective in reversing morbidity thought to be due to the pituitary tumors. In addition, there was evidence of reduced mTORC1 activity and increased apoptosis in the pituitary tumors.17

TSC Models in the Mouse: Tsc2+/− Mice (Table 1)

Table 1.

Tsc1 and Tsc2 Alleles in Mice and Rats

| Species | Gene | Allele name | Exon targeted/mutation | Major features of heterozygote animals | Major references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | Tsc2 | Eker | IAP element insertion into codon 1272 | Cystadenomas-carcinomas of kidney | 2–4, 39 |

| Splenic hemangiomas | |||||

| Uterine leiomyomas | |||||

| Pituitary adenomas | |||||

| Subependymal and subcortical hamartomas | |||||

| Mouse | Tsc2 | -, Kwiatkowski | Neomycin cassette insertion into exon 2 | Cystadenomas of kidney | 19 |

| Liver hemangiomas | |||||

| Extremity angiosarcomas | |||||

| Mouse | Tsc2 | -, Hino | Neomycin cassette insertion into exon 2, deletion of exons 2–5 | Cystadenomas of kidney | 28 |

| Liver hemangiomas | |||||

| Mouse | Tsc1 | -, Hino | Neomycin cassette insertion and deletion of exons 6–8 | Cystadenomas of kidney | 24 |

| Liver hemangiomas | |||||

| Mouse | Tsc1 | -, Kwiatkowski | Deletion of exons 17 and 18 | Cystadenomas of kidney | 25 |

| Liver hemangiomas | |||||

| Mouse | Tsc1 | -, Cheadle | Deletion of exons 6–8 with insertion of neomycin cassette | Cystadenomas of kidney | 27 |

| Liver hemangiomas | |||||

| Reduced survival of Tsc1+/− when in C57BL/6 strain | |||||

| Tsc1+/− kidney cancer in BALB/c strain | |||||

| Mouse | Tsc2 | neo, Gambello | Neomycin cassette insertion into exon 1 | Hypomorphic allele: Renal cysts only at 20 months of age Tsc2neo/neo embryos survive to E17 in some cases | 20 |

| Mouse | Tsc2 | del3, Kwiatkowski | Deletion of exon 3 | Hypomorphic allele: | 33 |

| Reduced severity of renal tumors | |||||

| 1-2 day longer survival of Tsc2del3/del3 embryos | |||||

| Mouse | Tsc2 | KO, Gambello | Deletion of exons 2–4 | Cystadenomas of kidney | 20 |

| Little published data | |||||

| Mouse | Tsc2 | -, Kobayashi | Deletion of exons 3–4 | Little published data | 32 |

Two different knockout (null, −) alleles of Tsc2 were independently derived and reported in 1999.18,19 The two different alleles were each made by targeting the second coding exon of Tsc2, though the precise constructs differed. Both of these Tsc2+/− mice have essentially identical phenotypes. More recently, a third null allele of Tsc2 has been reported, in which exons 2–4 are deleted, and which appears to have similar findings, though it has been studied in less detail.20

Tsc2+/− mice develop kidney tumors that are very similar to those of the Eker rat (Figs. 1 and 2). Kidney tumors develop by 6–12 months of age, and grow progressively throughout the life of the mouse.18,19 The tumors are cystadenomas consisting of a spectrum from pure cysts, to cysts with papillary projections, to solid adenomas. Major strain differences are seen in the number and size of these tumors, see further below. Renal carcinoma, characterized by nuclear atypia, massive growth, and metastatic disease develops in 5%–10% of mice by 18 months, indicating a very low rate (∼1 in 1,000) of malignant progression, given the overall numbers of these tumors, suggesting that additional genetic or epigenetic events are required for malignant progression.19

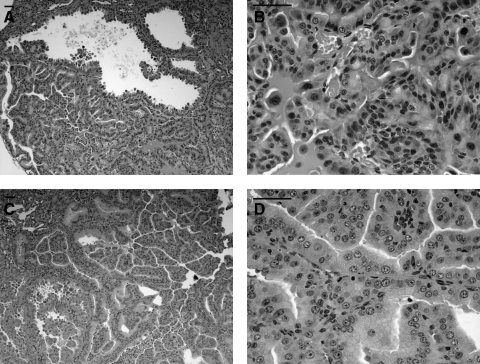

FIG. 1.

Tsc mouse liver hemangiomas. H&E stained pictures of liver hemangiomas from the Tsc1+/− (A, B: 14 months old) and Tsc2+/− mice (C, D: 12 months old) are shown. Note dilated aberrant, disorganized vascular channels with prominent hyperplastic endothelium, containing red blood cells. In C, some vessel lumens approach 1 mm in diameter, very large for the mouse. Scale bars 50 μm.

FIG. 2.

Tsc mouse kidney cystadenomas. H&E stained pictures of kidney cystadenomas from the Tsc1+/− (A, B; 14 months old) and Tsc2+/− mice (C, D; 12 months old) are shown. Note the prominent hyperplastic epithelial cells making up these tumors, with cell fragments in the lumen of some cystic regions. In B, note lack of organization and nuclear and cytoplasmic pleomorphism, consistent with malignancy. In all images, note prominent vascularization. Scale bars 50 μm.

Tsc2+/− mice also develop liver hemangiomas, characterized by mainly endothelial and some smooth muscle proliferation with large vascular spaces.18,19 These lesions are seen in about half of Tsc2+/− mice by 18 months of age, and can rupture with intraperitoneal hemorrhage leading to death. Hemangiosarcomas develop on the tail, paws, or mouth region in about 5% of Tsc2+/− mice by age 12 months. These lesions, consisting of proliferative spindle cells and aberrant vascular channels, do not metastasize but are malignant by cytologic criteria and exhibit bone invasion.

Similar to findings in the Eker rat, major strain-dependent differences in tumor development are seen in Tsc2+/− mice19 (Kwiatkowski et al., unpublished observations). The most dramatic difference is seen in comparison of the A/J and 129Sv/Jae strains. Age-matched Tsc2+/− A/J strain mice have about 10 times as many kidney tumors and 20 times the extent of kidney tumor as Tsc2+/− 129/SvJae mice. In contrast, liver hemangiomas are much more prevalent in Tsc2+/− 129/SvJae mice than in any other of 6 strains tested (Kwiatkowski et al. unpublished observations).

Histologic and immunohistochemical studies indicate that the cystadenomas arise in the cortical region of the kidney, and have an expression profile consistent with origin from the interstitial cell of the cortical collecting duct.19 The actin-binding protein gelsolin, which is normally expressed in interstitial cells of the kidney, was found to be overexpressed in all forms of cystadenoma and is a sensitive marker of early tumor development.

Similar to the Eker rate, LOH is seen fairly consistently (24%–50%) in both renal cystadenomas and liver hemangiomas, consistent with second hit genomic loss of the wild-type Tsc2 allele.18,19

VEGF levels are increased in both the kidney tumors, and in the serum of Tsc2+/− mice and Tsc2Eker/+ rats 21,22. VEGF levels are increased due to both mTOR-dependent and mTOR-independent pathways, and were associated with higher levels of each of HIF1α and HIF2α 21,23.

Tsc1+/− Mice (Table 1)

Two different knockout (null, −) alleles in Tsc1 were developed and reported in 2001–2002.24,25 One null allele was derived by insertion of a neo cassette and deletion of exons 6-8 of Tsc1,24 while the other was generated by a loxP strategy that generated a conditional allele of Tsc1 simultaneously, and had deletion of exons 17 and 18 of Tsc1.25 They have very similar phenotypes.

The tumors that occur in Tsc1+/− mice are entirely similar to those seen in Tsc2+/− mice (Figs. 1 and 2). However, renal tumor development was somewhat less in Tsc1+/− mice than in age-matched Tsc2+/− mice.24,25 In one Tsc1+/− mouse line developed, there was a clear sex-dependent difference in the frequency and severity of liver hemangiomas (higher in females than males), and this resulted in reduced survival of female compared with male mice.25 In addition, this sex-related difference in liver hemangiomas was confirmed in studies which examined the effects of estrogen and tamoxifen treatment on these mice. Estrogen enhanced liver hemangioma development in both male and female mice, while tamoxifen suppressed liver hemangioma development in females.26 This observation is clearly reminiscent of to the sex predilection of LAM, but is similarly poorly understood.

Analysis of one of these mouse models also provided the first in vivo evidence in a model system of the important role of the TSC1/TSC2 complex in regulating the state of mTORC1. Phospho-S6 levels were increased and phospho-AKT levels were reduced in mouse embryo fibroblasts that were Tsc1−/−; and phospho-S6 levels were shown to be increased in kidney tumor lysates from the Tsc1+/− mice.25

A third Tsc1 null allele was generated more recently by deletion of part of exon 6 and all of exons 7 and 8.27 The phenotype of these Tsc1+/− mice appeared somewhat different than the earlier two Tsc1+/− mice. First, in the C57BL/6 strain, but not the C3H or Balb/c strains, about one-quarter of Tsc1+/− pups died between birth and weaning, of uncertain causes. Second, there was a strikingly high incidence of renal carcinoma in Tsc1+/− BALB/c mice in comparison to two other strains, including some with sarcomatoid features and lung metastases.27 A comprehensive analysis of second hit events in the kidney lesions of these Tsc1+/− mice demonstrated that half to two-thirds of cystadenomas and renal cell carcinomas showed LOH for the wild-type allele, and about half of the remainder have a point mutation in the wild-type Tsc1 allele.28 However, very few cysts showed LOH or a small mutation in the wild-type allele of Tsc1. The authors concluded this indicated that cysts could develop from a haploinsufficiency mechanism.28 More recently, this group has demonstrated a high frequency of cell polarity defects in renal epithelial cells of Tsc1+/− and Tsc2+/− mice, and suggested that this may contribute to renal cyst formation.29 This again is thought to occur independent of second-hit events, and therefore due to haploinsufficiency of either Tsc1 or Tsc2.

In all, the relatively small differences seen in these three different Tsc1+/− mice suggest that the alleles have the same genetic and physiologic effects. The reported differences are likely due to either strain effects, or reflect the more detailed studies of certain aspects of phenotype in individual laboratories.

Mouse Models: Results from Tissue-Restricted Knockout of Tsc1 or Tsc2

LoxP-flanked (‘floxed’), conditional alleles of both Tsc1 and Tsc2 have been generated20,25,-30-33 (Table 2), and have been combined with various tissue-specific cre alleles. Although many interesting findings have been made in regard to the role of TSC1/TSC2 in multiple organs during development, none of these models have come close to reproducing the pathology seen in the kidney or the lungs in LAM and TSC. Since a neural crest origin has been proposed for AML and LAM, we have used a Wnt1-cre allele in combination with our Tsc1 conditional allele to attempt to create a mouse model of these conditions (Kwiatkowski and Larysz–Brysz, unpublished observations). Tsc1c/cWint1-cre+ mice died soon after birth from uncertain causes. They had normal orofacial development, and suckled milk appropriately. There was no renal or lung pathology apparent on histological sections.

Table 2.

Conditional Alleles of Tsc1 and Tsc2

Treatment Studies in the Mouse Models of TSC

Similar to results seen in the Eker rat, rapamycin and related mTORC1 inhibitors are very effective in blocking tumor development in the Tsc2+/− mouse model, and in subcutaneous tumor models using Tsc2 null MEF lines.34 Based upon an association between milder TSC renal disease and a high expressing allele of interferon gamma,35 treatment with interferon gamma has also been tested in the subcutaneous tumor model. Interferon gamma had some benefit but was not as effective as the rapamycin analogue CCI-779.36 Combination therapy with both did not appear to provide significant additional benefit over CCI-779 alone in the nude mouse model.37 More recently, NVP-BEZ235 (a dual pan-class 3 PI3kinase and mTOR inhibitor) has been tested on the renal tumors of Tsc2+/− mice.38 It was found to be equally effective to RAD001 (rapamycin analogue) alone. However, renal tumors in mice treated for one month with either drug rapidly grew back when the treatment was discontinued.

Conclusion

Although Tsc1 and Tsc2 rodent models do not match the pathology or pathophysiology seen in LAM and TSC patients, several important observations have been made in these systems. First, these tumors follow the two-hit mechanism of TSC tumor development, and demonstrate the same pathway effects that are seen in more limited detail in TSC patient tumors and lesions. They have been major tools in the assessment of potential therapies for TSC. Three different mTORC1 inhibitors (rapamycin, CCI-779, and RAD001) have been shown to have major therapeutic benefit in one TSC model or another. These studies have been critical in enabling and stimulating the current set of clinical trials with these compounds in TSC and LAM patients.

Though the liver and spleen hemangiomas of Tsc mice and rats bear some resemblance to AML and LAM, they are far from adequate. A major problem in developing an authentic AML/LAM model is insight into the cell type which gives rise to these lesions. The neural crest continues to be an attractive candidate for a cell of origin, and more sophisticated studies targeting this tissue during development are underway.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH NINDS NS031535 and P01 NS24279, NIH NCI P01 CA120964, and the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Kwiatokowski has no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

References

- 1.Eker R. Familial renal adenomas in Wistar rats; A preliminary report. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1954;34:554–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1954.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hino O. Klein–Szanto AJP. Freed JJ. Testa JR. Brown DQ. Vilensky M. Yeung RS. Tartof KD. Knudson AG. Spontaneous and radiation-induced renal tumors in the Eker rat model of dominantly inherited cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:327–331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung RS. Xiao GH. Jin F. Lee WC. Testa JR. Knudson AG. Predisposition to renal carcinoma in the Eker rat is determined by germ-line mutation of the tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11413–11416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eker R. Mossige J. Johannessen JV. Aars H. Hereditary renal adenomas and adenocarcinomas in rats. Diagn Histopathol. 1981;4:99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everitt J. Goldsworthy T. Wolf D. Walker C. Hereditary renal cell carcinoma in the Eker rat: A rodent familial cancer syndrome. J Urol. 1992;148:1932–1936. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi T. Hirayama Y. Kobayashi E. Kubo Y. Hino O. A germline insertion in the tuberous sclerosis (Tsc2) gene gives rise to the Eker rat model of dominantly inherited cancer. Nat Genet. 1995;9:70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung RS. Lessons from the Eker rat model: Ffrom cage to bedside. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:799–806. doi: 10.2174/1566524043359791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubo Y. Kikuchi Y. Mitani H. Kobayashi E. Kobayashi T. Hino O. Allelic loss at the tuberous sclerosis (Tsc2) gene locus in spontaneous uterine leiomyosarcomas and pituitary adenomas in the Eker rat model. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86:828–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb03092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeung RS. Xiao GH. Everitt JI. Jin F. Walker CL. Allelic loss at the tuberous sclerosis 2 locus in spontaneous tumors in the Eker rat. Mol Carcinog. 1995;14:28–36. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940140107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi T. Urakami S. Hirayama Y. Yamamoto T. Nishizawa M. Takahara T. Kubo Y. Hino O. Intragenic Tsc2 somatic mutations as Knudson's second hit in spontaneous and chemically induced renal carcinomas in the Eker rat model. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1997;88:254–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubo Y. Mitani H. Hino O. Allelic loss at the predisposing gene locus in spontaneous and chemically induced renal cell carcinomas in the Eker rat. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2633–2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi T. Mitani H. Takahashi R. Hirabayashi M. Ueda M. Tamura H. Hino O. Transgenic rescue from embryonic lethality and renal carcinogenesis in the Eker rat model by introduction of a wild-type Tsc2 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3990–4003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker CL. Hunter D. Everitt JI. Uterine leiomyoma in the Eker rat: A unique model for important diseases of women. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;38:349–356. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker CL. Cesen–Cummings K. Houle C. Baird D. Barrett JC. Davis B. Protective effect of pregnancy for development of uterine leiomyoma. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:2049–2052. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeung RS. Gu H. Lee M. Dundon TA. Genetic identification of a locus, Mot1, that affects renal tumor size in the rat. Genomics. 2001;78:108–112. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenerson HL. Aicher LD. True LD. Yeung RS. Activated mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in the pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis complex renal tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5645–5650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenerson H. Dundon TA. Yeung RS. Effects of rapamycin in the Eker rat model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:67–75. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000147727.78571.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi T. Minowa O. Kuno J. Mitani H. Hino O. Noda T. Renal carcinogenesis, hepatic hemangiomatosis, and embryonic lethality caused by a germ-line Tsc2 mutation in mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1206–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onda H. Lueck A. Marks PW. Warren HB. Kwiatkowski DJ. Tsc2(+/−) mice develop tumors in multiple sites that express gelsolin and are influenced by genetic background. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:687–695. doi: 10.1172/JCI7319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernandez O. Way S. McKenna J., 3rd Gambello MJ. Generation of a conditional disruption of the Tsc2 gene. Genesis. 2007;45:101–106. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu MY. Poellinger L. Walker CL. Up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha in renal cell carcinoma associated with loss of Tsc-2 tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2675–2680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Hashemite N. Walker V. Zhang H. Kwiatkowski DJ. Loss of Tsc1 or Tsc2 induces vascular endothelial growth factor production through mammalian target of rapamycin. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5173–5177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brugarolas JB. Vazquez F. Reddy A. Sellers WR. Kaelin WG., Jr. TSC2 regulates VEGF through mTOR-dependent and -independent pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi T. Minowa O. Sugitani Y. Takai S. Mitani H. Kobayashi E. Noda T. Hino O. A germ-line Tsc1 mutation causes tumor development and embryonic lethality that are similar, but not identical to, those caused by Tsc2 mutation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8762–8767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151033798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwiatkowski DJ. Zhang H. Bandura JL. Heiberger KM. Glogauer M. el-Hashemite N. Onda H. A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex-dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up-regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:525–534. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El–Hashemite N. Walker V. Kwiatkowski DJ. Estrogen enhances whereas tamoxifen retards development of Tsc mouse liver hemangioma: A tumor related to renal angiomyolipoma and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2474–2481. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson C. Idziaszczyk S. Parry L. Guy C. Griffiths DF. Lazda E. Bayne RA. Smith AJ. Sampson JR. Cheadle JP. A mouse model of tuberous sclerosis 1 showing background specific early post-natal mortality and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1839–1850. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson C. Bonnet C. Guy C. Idziaszczyk S. Colley J. Humphreys V. Maynard J. Sampson JR. Cheadle JP. Tsc1 haploinsufficiency without mammalian target of rapamycin activation is sufficient for renal cyst formation in Tsc1+/- mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7934–7938. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonnet CS. Aldred M. von Ruhland C. Harris R. Sandford R. Cheadle JP. Defects in cell polarity underlie TSC and ADPKD-associated cystogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2166–2176. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meikle L. McMullen JR. Sherwood MC. Lader AS. Walker V. Chan JA. Kwiatkowski DJ. A mouse model of cardiac rhabdomyoma generated by loss of Tsc1 in ventricular myocytes. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:429–435. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rachdi L. Balcazar N. Osorio–Duque F. Elghazi L. Weiss A. Gould A. Chang–Chen KJ. Gambello MJ. Bernal–Mizrachi E. Disruption of Tsc2 in pancreatic {beta} cells induces {beta} cell mass expansion and improved glucose tolerance in a TORC1-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9250–9255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803047105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shigeyama Y. Kobayashi T. Kido Y. Hashimoto N. Asahara S. Matsuda T. Takeda A. Inoue T. Shibutani Y. Koyanagi M. Uchida T. Inoue M. Hino O. Kasuga M. Noda T. Biphasic response of pancreatic beta-cell mass to ablation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2971–2979. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01695-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollizzi K. Malinowska–Kolodziej I. Doughty C. Betz C. Ma J. Goto J. Kwiatkowski DJ. A hypomorphic allele of Tsc2 highlights the role of TSC1/TSC2 in signaling to AKT and models mild human TSC2 alleles. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2378–2387. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee L. Sudentas P. Donohue B. Asrican K. Worku A. Walker V. Sun Y. Schmidt K. Albert MS. El–Hashemite N. Lader AS. Onda H. Zhang H. Kwiatkowski DJ. Dabora SL. Efficacy of a rapamycin analog (CCI-779), IFN-gamma in tuberous sclerosis mouse models. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;42:213–227. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dabora SL. Roberts P. Nieto A. Perez R. Jozwiak S. Franz D. Bissler J. Thiele EA. Sims K. Kwiatkowski DJ. Association between a high-expressing interferon-gamma allele and a lower frequency of kidney angiomyolipomas in TSC2 patients. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:750–758. doi: 10.1086/342718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee L. Sudentas P. Dabora SL. Combination of a rapamycin analog (CCI-779) and interferon-gamma is more effective than single agents in treating a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:933–944. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Messina MP. Rauktys A. Lee L. Dabora SL. Tuberous sclerosis preclinical studies: timing of treatment, combination of a rapamycin analog (CCI-779) and interferon-gamma, and comparison of rapamycin to CCI-779. BMC Pharmacol. 2007;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollizzi K. Malinowska–Kolodziej I. Stumm M. Lane H. Kwiatkowski D. Equivalent benefit of mTORC1 blockade and combined PI3K-mTOR blockade in a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeung RS. Katsetos CD. Klein–Szanto A. Subependymal astrocytic hamartomas in the Eker rat model of tuberous sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1477–1486. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]