Abstract

Purpose

Noninvasive and convenient biomarkers for early diagnosis of breast cancer remain an urgent need. The aim of this study was to discover and identify potential protein biomarkers specific for breast cancer.

Methods

Two hundred and eighty-two (282) serum samples with 124 breast cancer and 158 controls were randomly divided into a training set and a blind-testing set. Serum proteomic profiles were analyzed using SELDI-TOF-MS. Candidate biomarkers were purified by HPLC, identified by LC-MS/MS and validated using ProteinChip immunoassays and western blot technique.

Results

A total of 3 peaks (m/z with 6,630, 8,139 and 8,942 Da) were screened out by support vector machine to construct the classification model with high discriminatory power in the training set. The sensitivity and specificity of the model were 96.45 and 94.87%, respectively, in the blind-testing set. The candidate biomarker with m/z of 6,630 Da was found to be down-regulated in breast cancer patients, and was identified as apolipoprotein C-I. Another two candidate biomarkers (8,139, 8,942 Da) were found up-regulated in breast cancer and identified as C-terminal-truncated form of C3a and complement component C3a, respectively. In addition, the level of apolipoprotein C-I progressively decreased with the clinical stages I, II, III and IV, and the expression of C-terminal-truncated form of C3a and complement component C3a gradually increased in higher stages.

Conclusions

We have identified a set of biomarkers that could discriminate breast cancer from non-cancer controls. An efficient strategy, including SELDI-TOF-MS analysis, HPLC purification, MALDI-TOF-MS trace and LC-MS/MS identification, has been proved very successful.

Keywords: Biomarker, Breast cancer, LC-MS/MS, MALDI-TOF-MS, Proteomics, SELDI-TOF-MS

Background

Breast cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-related death in women, and it approximately accounts for 26% of all new female cancer cases in 2008 in the USA (Jemal et al. 2008). The course of this disease at the early stages is almost asymptomatic and, thus, the majority of cases are diagnosed in later stages when most of them have lost chances for cure (De Gelder et al. 2008). The 5-year survival rates of breast cancer decrease from 98% for early stage to 39% for late stage disease (Redondo et al. 2008). Hence, early, accurate diagnosis and timely treatment is critical for improving long-term survival of breast cancer patients. Current screening methods used to detect breast tumors include clinical examination, ultrasound, and mammography (Kroman et al. 2007). Although mammography is the most acute approach, there are intrinsic limitations to mammography (Cherel et al. 2008). To be detected in mammography, a breast tumor should be at least a few millimeters in size (Ding et al. 2008). However, a tumor of this size already contains several hundred thousand cells, and given that a single cell can lead to the development of a whole tumor, it is already late when a breast tumor is detected by mammography. For a long time, researchers have been seeking valuable biomarkers for breast cancer, such as TPS, CA125, CA15-3, and CEA proteins. To our disappointment, all these biomarkers either lack specificity to some degree, or have a poor positive predictive value (Zhu and Michael 2007; Grabiec et al. 2005; Agyei Frempong et al. 2008; Zheng and Luo 2005). Noninvasive and specific biomarkers for early diagnosis of breast cancer remain an urgent need.

Proteome analysis provides valuable information about total proteome’s dynamic and rapid changes with the processes of illness. Recent advances in proteomics have offered opportunities for finding biomarkers in biological fluids, especially in serum. Surface-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (SELDI-TOF-MS), which generated the protein fingerprint by MS, has been proved a powerful tool for potential biomarker discovery (Tomosugi 2004; Luo et al. 2008). Recently, the SELDI-TOF-MS analysis has been successfully used to identify specific biomarkers for various cancers, such as ovarian cancer (Wang et al. 2008), prostate cancer (Skytt et al. 2007), pancreatic cancer (Liu et al. 2008), colon cancer (Hundt et al. 2007), etc. Several studies have reported the potential of SELDI to provide serum biomarkers that differentiate breast cancer from benign disease and healthy subjects. A few pilot studies based on proteomics were conducted in search of biomarkers for diagnosing breast cancer, in which SELDI-TOF-MS has been utilized (Li et al. 2002; Laronga et al. 2003; Hu et al. 2005a, b; Belluco et al. 2007). However, to our knowledge, no specific protein biomarkers have been identified and validated in these reports.

In this study, we used SELDI-TOF-MS technology to screen potential protein patterns specific for breast cancer and then purified the candidate protein biomarker peaks by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), identified by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and finally confirmed these biomarkers by ProteinChip immunoassays.

Materials and methods

Patients and serum samples

Serum samples were obtained from 282 individuals with informed consent by the Department of General Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. These serum samples were collected from 124 patients with breast cancer, 98 patients with benign breast diseases, and 60 healthy individuals. Patients with breast cancer had a median age of 47.8 years (ranging from 18 to 76 years, 1 man and 123 women). All 124 patients were distributed in 4 stages according to UICC. In stage I there were 85 patients; stage II, III and IV consisted of 18, 12 and 9 patients, respectively. The benign breast diseases group and the healthy individuals group were age- and gender-matched with the breast cancer group. Pathological diagnosis of all the breast cancer and benign breast diseases were confirmed independently by two pathologists. All serum samples were collected preoperatively in the morning before breakfast. The sera were left at room temperature for 1 h, centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min, and then stored at −80°C.

Reagents and instruments

Sinapinic acid (SA) was purchased from Fluka (USA). ProteinChip Biosystems (Ciphergen PBS-II plus SELDI-TOFMS) and weak cation exchange (WCX) chip were purchased from Ciphergen Biosystems (USA). All other SELDI-TOF-MS related reagents were acquired from Sigma (USA). Ziptip C18 was purchased from Millipore (USA). Trypsase was purchased from Promega (USA). IAM was purchased from AppliChem (GER). DTT was purchased from BIO-RAD (GER). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectroscopy (MALDI-TOF-MS) was purchased from Kratos Analytical Co (UK) and HPLC was purchased from Shimadzu (JPN). LC-MS/MS was purchased from Thermo Electron Corporation (USA).

SELDI-TOF-MS analysis of serum protein profiles

Protein profiling of serum samples was determined by SELDI-TOF-MS using the WCX2 (weak cation exchange) Proteinchip arrays (Ciphergen Biosystems, USA). Frozen serum samples were thawed on ice and spun at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Each serum sample (10 μL) was denatured by addition of 20 μL of U9 buffer (9 M urea, 2% CHAPS, 50 mM Tris–HCl, 1% DTT, pH 9.0) and vortexed at 4°C for 30 min. Each sample was then diluted in 108 μL of low-stringency buffer (0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 4.0) and 100 μL of each diluted serum sample was then ready to hybridize with WCX2 proteinchip arrays, which was held by a bioprocessor (Ciphergen Biosystems) and preactivated twice with 150 μL low-stringency buffer at room temperature for 5 min. The diluted serum sample was allowed to react with the surface of the WCX2 chip for 60 min at room temperature. Each spot was then washed three times with appropriate buffers of various pHs and ionic strengths to eliminate non-adsorbed proteins. After drying the array surface in the air, 1 μL saturated sinapinic acid (SA) matrix in 50% ACN and 0.5% TFA was applied and allowed to dry. MS analysis was performed on a PBS-II ProteinChip reader (Ciphergen Biosystems). Mass peak detection was analyzed using ProteinChip Biomarker Software version 3.1 (Ciphergen Biosystems). The mass spectra of the proteins were generated using an average of 140 laser shots at a laser intensity of 170 arbitrary units and detector sensitivity was set at 6. For data acquisition of low-molecular weight proteins, the optimize detection mass range was set from 2 to 20 kDa for all study sample profiles. The instrument was calibrated by the All-in-one peptide molecular mass standard (Ciphergen Biosystems).

Bioinformatics and biostatistics

Patients with breast cancer were split into a training set and a blind-testing set; 80 samples of breast cancer patients and 40 healthy controls were selected for a training sample set at random. To evaluate the accuracy and validity of the classification model, the remaining 44 samples of breast cancer patients and 118 controls (20 healthy controls and 98 patients with benign breast diseases) were selected for a blind-testing set (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study population used in SELDI experiment

| Breast cancer patients | Controls | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | 80 | 40 h | 120 |

| Testing set | 44 | 118 (20 h + 98 p) | 162 |

| Total | 124 | 158 | 282 |

h Healthy controls, p patients with benign breast diseases

The first step of data analysis was to use the undecimated discrete wavelet transform (UDWT) method to denoise the signals. Second, the spectra were subjected to baseline correction by aligning with a monotone local minimum curve and mass calibration. The proteomic peaks were detected and quantified by an algorithm that takes the maximal height of every denoised, baseline-corrected, and calibrated mass spectrum into account. Third, the peaks were filtered to maintain a signal to noise ratio (S/N) of more than three. The S/N of a peak is the ratio of the height of the peak above the baseline to the wavelet-defined noise. Finally, to match peaks across spectra, we pooled the detected peaks if the relative difference in their mass sizes was not more then 0.3%. The minimal percentage of each peak, appearing in all the spectra, is specified to ten. The matched peak across spectra is defined as a peak cluster. If a spectrum does not have a peak within a given cluster, the maximal height within the cluster will be assigned to its peak value. The normalization was performed only with the identified peak clusters.

To distinguish between data of different groups, we used a nonlinear support vector machine (SVM) classifier, originally developed by Vladimir Vapnik, with a radial-based function kernel, a parameter Gamma of 0.6, and a cost of the constrain violation of 19. The leave-one-out crossing validation approach was applied to estimate the accuracy of this classifier. The capability of each peak in distinguishing data of different groups was estimated by the P value of Wilcoxon t test. The P value was set at 0.01 to be statistically significant. The remaining 44 samples of breast cancer patients and 118 controls (20 healthy controls and 98 patients with benign breast diseases), were analyzed to test the classification model. Breast cancer and control samples were then discriminated based on their proteomic profile characteristics. The sensitivity was defined as the probability of predicting breast cancer cases; the specificity was defined as the probability of predicting control samples. The positive predictive value was defined as the probability of breast cancer if a test result was positive.

Serum fractionation

Serum samples both from healthy controls and breast cancer patients were selected for the purification of the three candidate protein biomarkers. The serum sample was mixed with U9 buffer (1:2, v/v) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The sample was then diluted in 5 mL WCX binding buffer (50 mM NaAc, pH 4.0) and loaded to the CM Ceramic Hyper D WCX SPE column (6 × 10 mm, Pall Life science, USA). After washing with 2 mL of WCX binding buffer, the column was eluted with 5 mL of eluting buffer (2 M NaCl, 50 mM NaAc, pH 4.0) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The eluted fraction was further purified using HPLC.

Purification of candidate protein markers using HPLC

HPLC separation was performed using SCL-10AVP (Shimadzu, Japan) with a Sunchrom C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size, 300 Å) (The Great Eur-Asia Sci-Tech Development Co. Ltd, Beijing, China) and a C18 guard column (10 × 3 mm, Shimadzu, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (5% ACN, 0.1% TFA) and solvent B (90% ACN, 0.1% TFA). The HPLC separation was achieved with a linear solvent gradient: 100% A (0 min)–15% B (15 min)–65% B (65 min)–100% B (100 min) at a flow-rate of 0.5 mL/min. The eluate was detected at multiple wavelengths of 214, 254, 280 nm. Each peak fraction was collected and concentrated using SpeedVac, and then analyzed using AXIMA-CFRTM plus MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Shimadzu/Kratos, Manchester, UK) in linear mode to trace the candidate protein biomarkers with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) as matrix.

Identification of candidate protein biomarkers by LC-MS/MS

In-solution digestion of each concentrated fraction, which contains one candidate protein biomarker, was performed with a standard protocol. Briefly, each fraction was dissolved in 25 mM NH4HCO3, and reduced with 10 mM DTT for 1 h, alkylated by 40 mM iodoacetamide in the dark for 45 min at room temperature, and then 40 mM DTT was added to quench the iodoacetamide for 30 min at room temperature. Then proteins were proteolysed with 20 ng of modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) in 25 mM NH4HCO3 overnight at 37°C. The supernatant was collected and peptides were further extracted in 0.1% acetic acid and 60% acetonitrile. Peptide extracts were vacuum dried and resuspended in 20 μl of water for mass analysis. Protein digests obtained above were loaded onto a home-made C18 column (100 mm × 100 μm) packed with Sunchron packing material (SP-120-3-ODS-A, 3 μm) and followed with nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. The LTQ mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode in which first the initial MS scan recorded the mass to charge (m/z) ratios of ions over the mass range from 400 to 2,000 Da, and then the five most abundant ions were automatically selected for subsequent collision-activated dissociation. All MS/MS data were searched against a human protein database downloaded from national center for biotechnology information (NCBI) using the SEQUEST program (Thermo, USA).

Confirmation of candidate protein biomarkers using ProteinChip immunoassays

To confirm the identity of the candidate protein biomarkers, all samples from the initial experiments were reanalyzed by using ProteinChip immunoassays (Ciphergen Biosystems). Specific antibody arrays were prepared by covalently coupling the appropriate antibodies to preactivated ProteinChip arrays (Ciphergen Biosystems). Antibodies (anti-apolipoprotein C-I goat antibody, AB824; anti-C3a mouse antibody, CM252374) were covalently coupled to PS20 arrays, respectively. After blocking with BSA and washing to remove uncoupled antibodies, antibody-coated spots was incubated with 1.5 μL of serum samples and 3 μL of binding buffer (0.1 M Na3PO4, 0.5 M urea, 0.5% CHAPS, pH 7.2) for 90 min. Spots were then washed with PBST (0.5% Triton X-100), PBS and deionized water twice, respectively, before drying. SELDI-TOF-MS analysis was performed on a PBS-II ProteinChip reader with CHCA as matrix.

Western blot validation

All samples from the initial experiments were heated to 95°C for 10 min before separating on 18% Tris/glycine/SDS acrylamide gels (Bio-Rad). The proteins were subsequently transblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF; Miniproe) membranes and blocked for 2 h at room temperature in 5% dry milk. The immunoblots were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with goat anti-apolipoprotein C-I antibody (chemicon) and mouse anti-C3a antibody (Hong Kong), respectively. After three washes with TBS/0.05% Tween-20, the blots were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat antibody and rabbit anti-mouse antibody (chemicon) for 1 h at 37°C, respectively. Protein signal was visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (PIERCE) and detected with Imaging System. GAPDH protein was visualized and detected as above. Images of blots were captured with an Apple scanner, and densitometric analysis of bands was performed using Scion software for Macintosh. Background values were subtracted, and multiple blots were combined for statistical analysis.

Results

Serum protein profiles and data processing

Serum samples from the training set were analyzed compared by SELDI-TOF-MS with WCX2 chip. All MS data were baseline subtracted, normalized using total ion current, and the peak clusters were generated by Biomarker Wizard software. After carrying out Wilcoxon rank sum tests to test relative signal strength, 28 peaks with P value <0.01 were obtained. Nineteen protein peaks were found up-regulated and nine peaks were found down-regulated in breast cancer group (data not shown). From the random combination of protein peaks with remarkable variation, SVM screened out the combined model with the maximum Youden index of the predicted value, identifying 3 markers positioned at 6,630, 8,139 and 8,942, respectively. In the breast cancer group, the 6,630 Da protein was significantly decreased while 8,139 and 8,942 Da proteins were remarkably elevated (Fig. 1). The descriptive statistics of these three markers are shown in Table 2. In addition, the level of 6,630 Da protein progressively decreased with the clinical stages I, II, III and IV, and the expression of 8,139, 8,942 Da proteins gradually increased in higher stages (Fig. 2). Combining three potential markers, using the method of leave-1-out to make crossing detection, the sensitivity of discriminating 80 and 40 normal subjects was 97%, and its specificity was 96%.

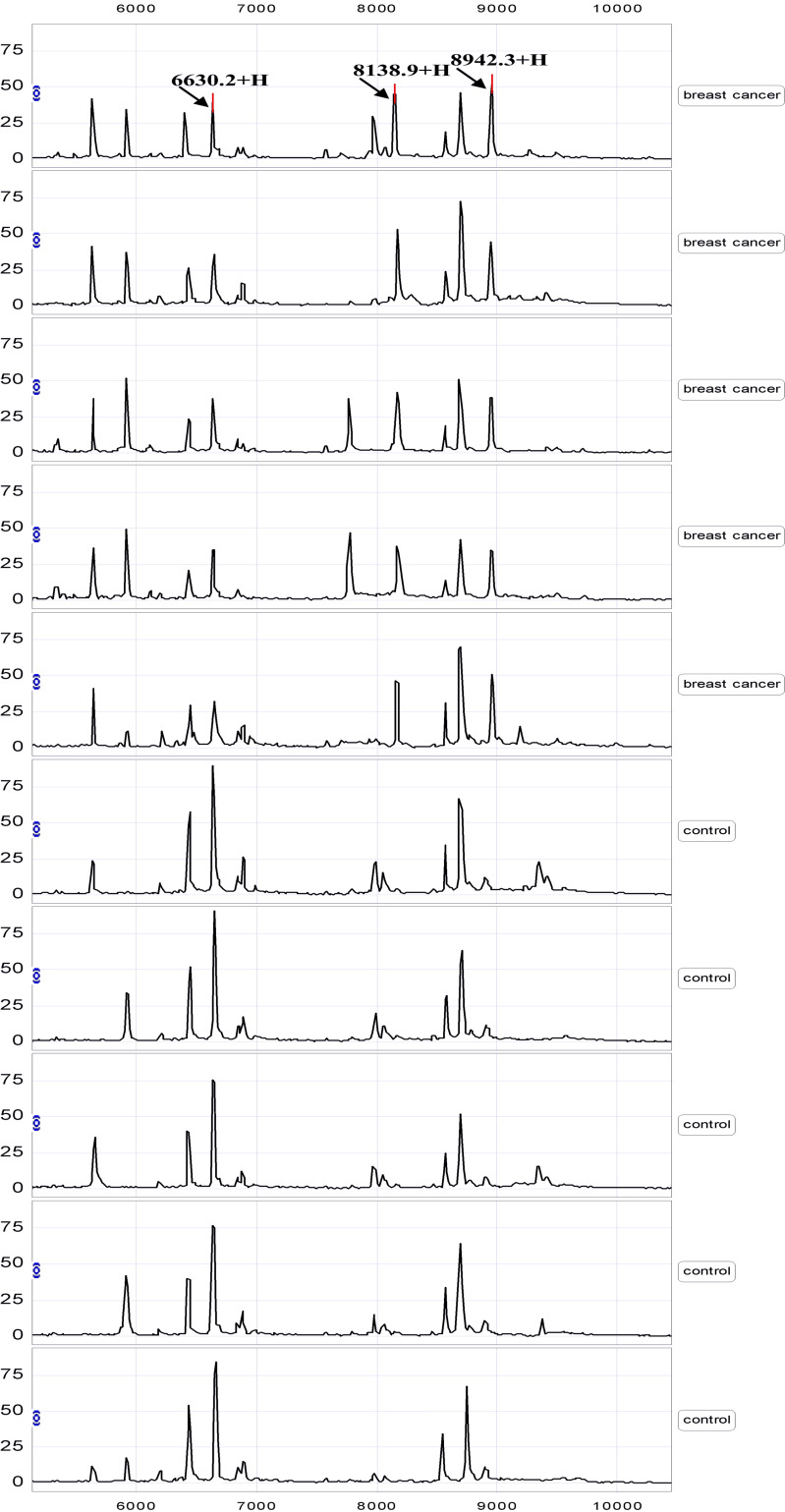

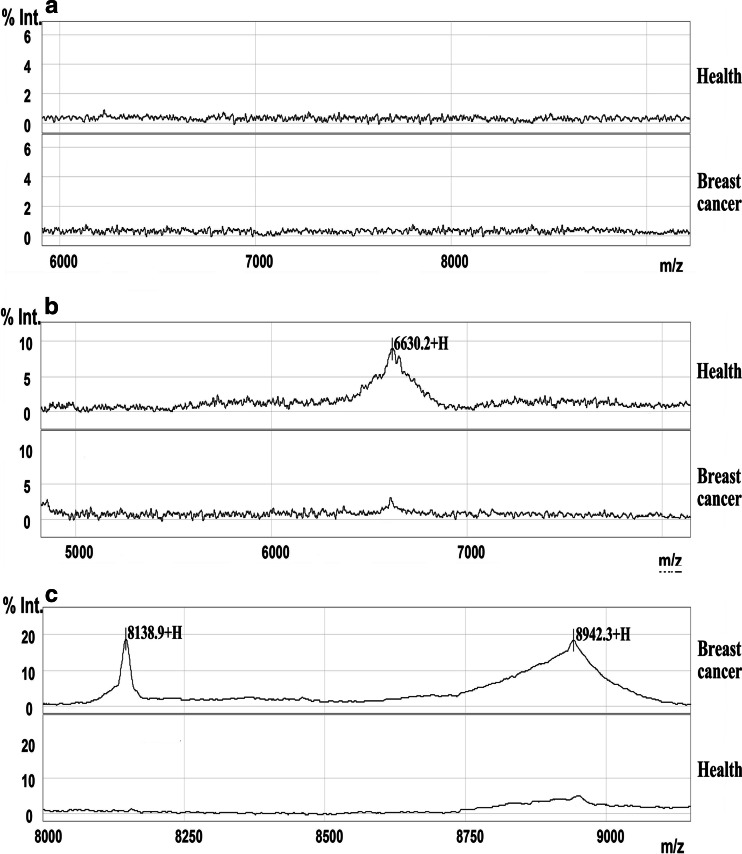

Fig. 1.

A representative spectrum of SELDI-TOF-MS analysis of sera from breast cancer patients and healthy controls. Differentially expressed proteins with potential diagnostic significance are arrowed. Top group denotes sera from patients with breast cancer, in which 8,139 and 8,942 m/z were over-expressed. Bottom group denotes sera from healthy individuals, in which 6,630 m/z was up-regulated

Table 2.

The relative peak intensity of three distinct protein spectra found in sera of breast cancer patients

| m/z | Patients with breast cancer (mean ± SD) | Healthy individuals (mean ± SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6,630 | 2,776.54 ± 579.17 | 6,793.27 ± 1,488.34 | 0.001381 |

| 8,139 | 3,271.98 ± 600.28 | 238.62 ± 109.08 | 0.000538 |

| 8,942 | 3,308.26 ± 614.53 | 256.43 ± 119.05 | 0.000672 |

Fig. 2.

A representative spectrum of SELDI-TOF-MS analysis of sera from different stages of breast cancer patients and non-cancer controls. The level of 8,139, 8,942 Da proteins progressively increased with the clinical stages I, II, III and IV, and the expression of 6,630 Da protein gradually decreased with the stage increasing

Protein peak validation

The remaining 44 breast cancer and 118 control serum samples (20 healthy controls and 98 patients with benign breast diseases), as a blind-testing set, were analyzed to validate the accuracy and validity of the classification model derived from the training set. The descriptive statistics of the three markers in 44 patients and 118 control serum is shown in Table 3. The classification model discriminated the breast cancer samples from controls with a sensitivity of 96.45% and a specificity 94.87%, and positive predictive value of 96.0%, respectively. The area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve of this model was 0.972.

Table 3.

The relative peak intensity of the three markers in the blind-testing set

| m/z | Patients with breast cancer (n = 44) (mean ± SD) | Non-cancer controls (n = 118) (mean ± SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6,630 | 2,665.34 ± 567.13 | 6,729.22 ± 1,459.41 | 0.001296 |

| 8,139 | 3,298.72 ± 609.57 | 229.35 ± 103.92 | 0.000493 |

| 8,942 | 3,339.02 ± 624.36 | 245.43 ± 115.03 | 0.000623 |

Purification and identification of candidate protein biomarkers

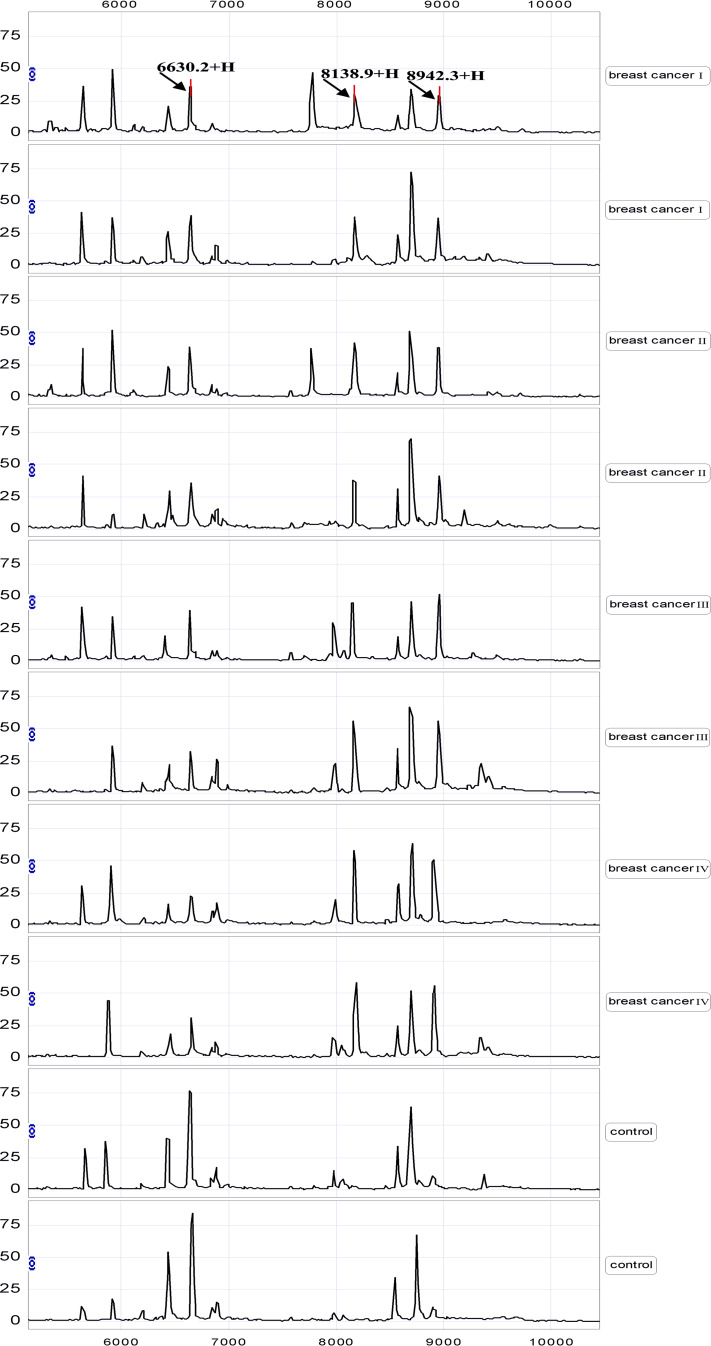

Serum samples from healthy controls were used for the purification of the down-regulated candidate protein biomarker (6,630 Da), and serum samples from breast cancer patients were used for the purification of the two up-regulated proteins (8,139, 8,942 Da) using WCX SPE and C18 HPLC. Figure 3 shows the results of MALDI-TOF-MS analysis of the three purified candidate protein biomarkers.

Fig. 3.

MALDI-TOF-MS spectra of three purified potential protein markers

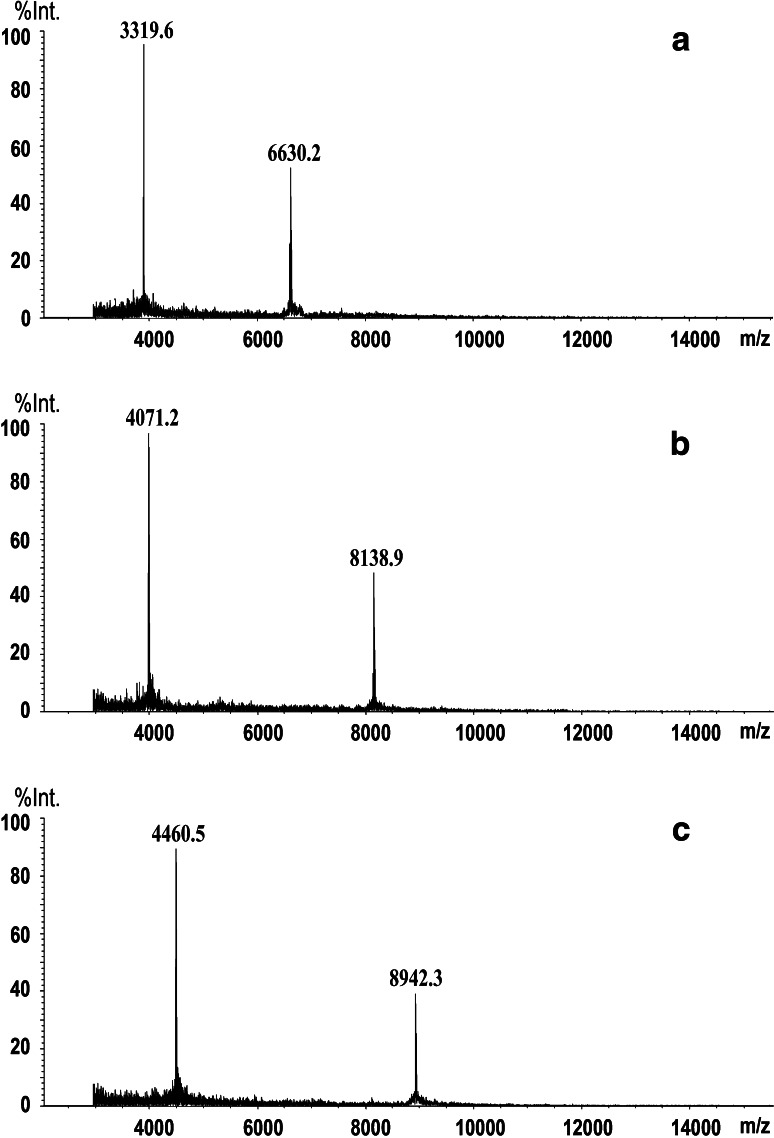

After digestion with modified trypsin, the peptide mixture was analyzed by nano-LC-MS/MS. Figure 4 shows the results of the LC-MS/MS chromatogram (Fig. 4a) and MS/MS spectrum of two identified peptides (Fig. 4b, c) from protein (8,942 Da). Table 4 shows the results of identification of the three candidate protein biomarkers. They were apolipoprotein C-I (6,630 Da), C-terminal-truncated form of C3a (8,139 Da) and complement component C3a (8,942 Da). Combination of high sequence coverage and accurate MW measurement by MALDI-TOF-MS gave the whole sequence of the three candidate protein markers.

Fig. 4.

Results of the identification of protein (8,942 Da) by LC-MS/MS. a Chromatogram of peptide mixture; b, c MS/MS spectra of two peptides

Table 4.

Identification of the three potential protein biomarkers with identified peptides and covered sequence

| m/z | Protein name | Peptides identified | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6,631 | Apolipoprotein C-I | G.TPDVSSALDK.L | tpdvssaldklkefgntledkarelisrikqselsakmrewfsetfqkvkeklkids |

| R.EWFSETFQK.V | |||

| K.EFGNTLEDKAR.E | |||

| K.LKEFGNTLEDK.A | |||

| K.MREWFSETFQK.V | |||

| G. TPDVSSALDKLK.A | |||

| K.ARELISRIK.Q | |||

| 8,139 | C-terminal-truncated form of C3a | R.SVQLTEKRMDK.V | svqltekrmdkvgkypkelrkccedgmrenpmrfscqrrtrfislgeackkvfldccnyitelrrqha |

| R.MDKVGKYPK.E | |||

| K.ELRKCCEDGMR.E | |||

| R.ENPMRFSCQR.R | |||

| K.KVFLDCCNYITELR.R | |||

| K.VFLDCCNYITELRRQHA.R | |||

| 8,942 | Complement component C3a | R.SVQLTEKRMDK.V | svqltekrmdkvgkypkelrkccedgmrenpmrfscqrrtrfislgeackkvfldccnyitelrrqharashlgla |

| K.RMDKVGKYPKELRK.C | |||

| K.ELRKCCEDGMR.E | |||

| R.ENPMRFSCQR.R | |||

| K.KVFLDCCNYITELR.R | |||

| K.VFLDCCNYITELRRQHAR.A |

Bold letters show the covered sequence by identified peptide

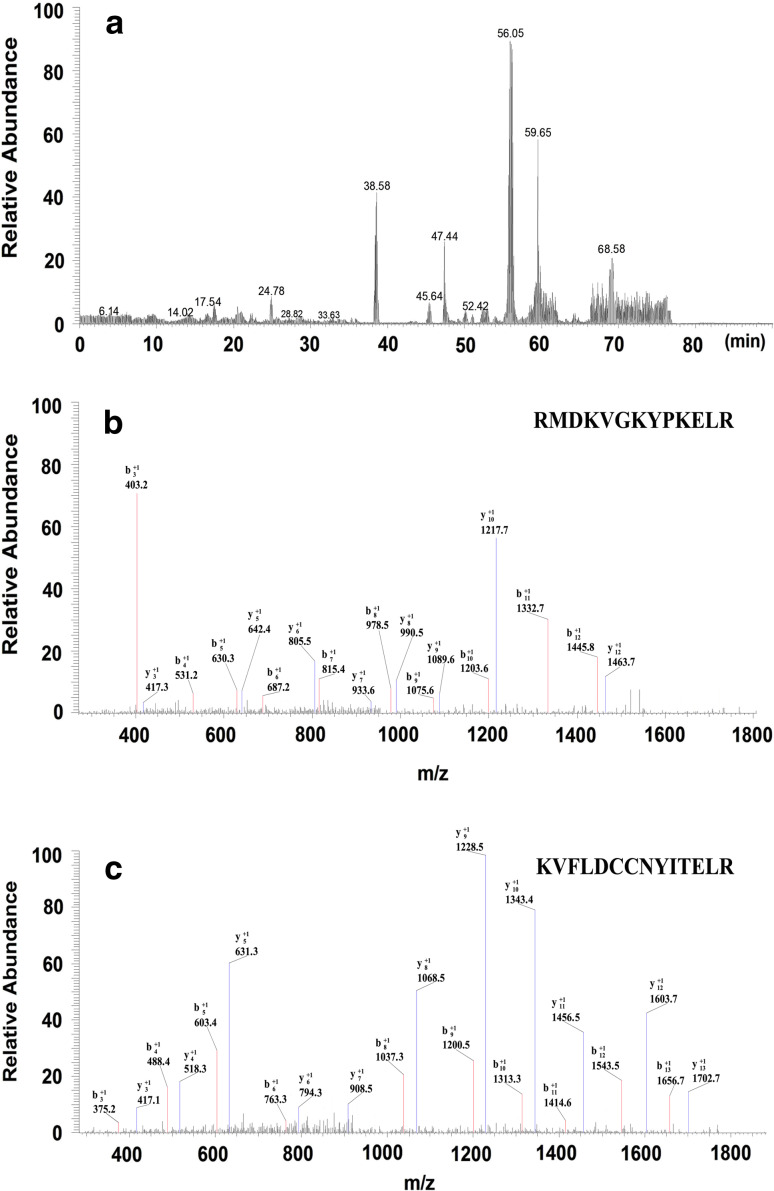

Validation of three candidate protein biomarkers using ProteinChip immunoassays

To confirm the three identified proteins apolipoprotein C-I, C-terminal-truncated form of C3a and complement component C3a, we performed immunoassay with immobilization of specific antibodies to three proteins on a ProteinChip (Ciphergen Biosystems). The results showed that apolipoprotein C-I was captured and detected in the serum of healthy controls, and C-terminal-truncated form of C3a and complement component C3a in the serum of breast cancer patients (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Representative spectra from ProteinChip array with immobilized antibodies against apolipoprotein C-I (b), complement component C3a (c) for breast cancer patients and healthy individuals and representative spectra of the negative control (nonspecific mouse IgG; a)

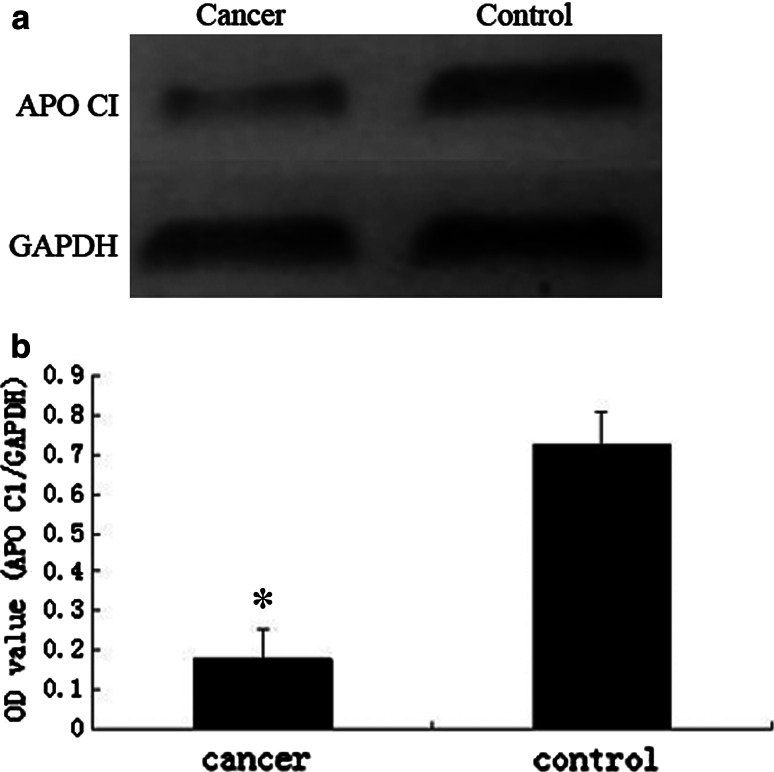

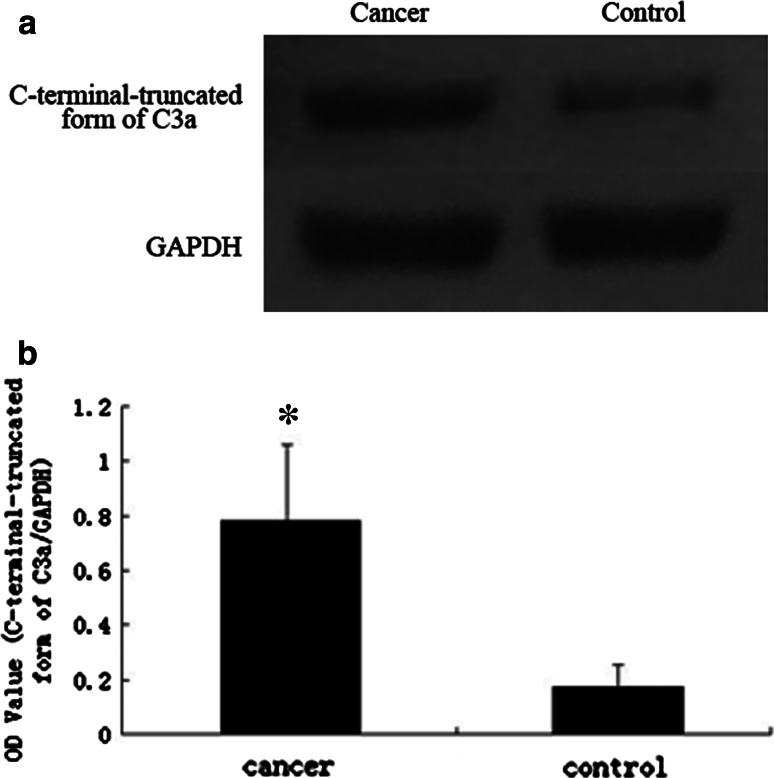

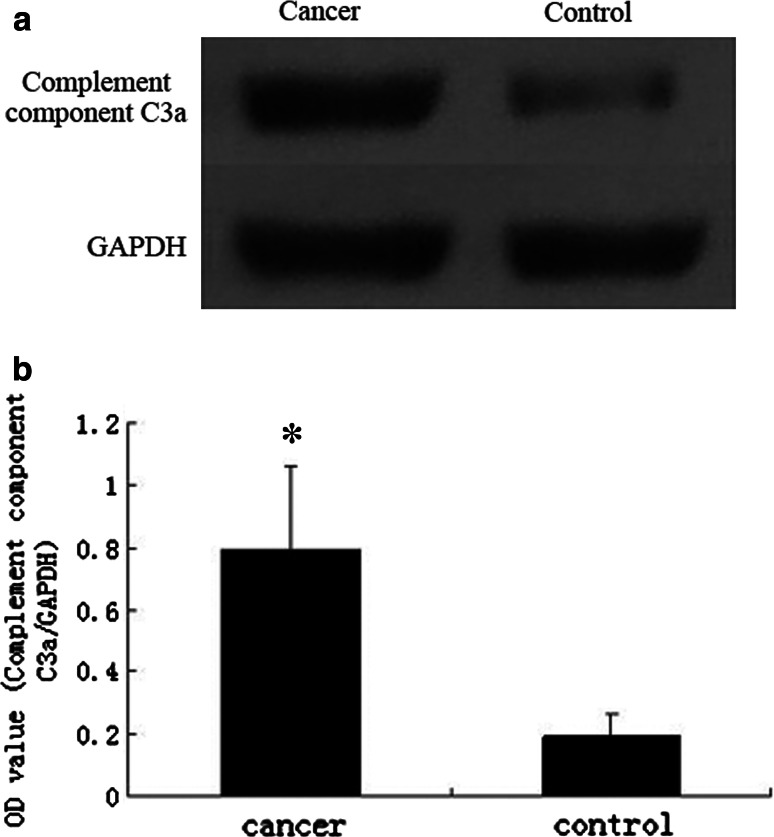

Western blot analysis of three candidate protein biomarkers

To confirm the protein identification and differential expression of apolipoprotein C-I, C-terminal-truncated form of C3a and complement component C3a in breast cancer sera, we conducted western blot for validation. The expression levels of apolipoprotein C-I in breast cancer group and non-cancer control group were 0.177 ± 0.747 and 0.725 ± 0.186, respectively. The levels of C-terminal-truncated form of C3a in breast cancer group and non-cancer control group were 0.781 ± 0.270 and 0.187 ± 0.069, while the levels of complement component C3a were 0.799 ± 0.280 and 0.197 ± 0.072, respectively. Statistical analysis showed that the apolipoprotein C-I (Fig. 6) was significantly decreased (P < 0.001), while C-terminal-truncated form of C3a (Fig. 7) and complement component C3a (Fig. 8) were remarkably elevated in the breast cancer group comparing with non-cancer control group (P < 0.001).

Fig. 6.

a Western blots of apolipoprotein C-I (APO CI) in sera from breast cancer and non-cancer control. b The expression of APO CI in breast cancer patients is lower than non-cancer controls. In comparison with the control group, there is significant difference between them (*t = −22.951, P < 0.001)

Fig. 7.

a Western blots of C-terminal-truncated form of C3a in sera from breast cancer and non-cancer control. b The expression of C-terminal-truncated form of C3a in breast cancer patients is higher than non-cancer controls. In comparison with the control group, there is significant difference between them (*t = 13.684, P < 0.001)

Fig. 8.

a Western blots of complement component C3a in sera from breast cancer and non-cancer control. b The expression of C3a in breast cancer patients is higher than non-cancer controls. In comparison with the control group, there is significant difference between them (*t = 13.974, P < 0.001)

Discussion

Breast cancer is believed to result from the accumulation of oncogene mutations or rearrangements and silencing of tumor suppressor genes. During tumor growth, specific tumor-secreted proteins, normal tissue- and plasma-protein digested by tumor-secreted proteases, and proteins produced by local and distant responses to the tumor would be released into blood (Hansh et al. 2008). Since whole blood is in contact with practically all tissues in the human body and is considered to provide a dynamic reflection of physiological and pathological status, serum often changes prior to the detection of any other clinical symptoms and has diagnostic value for early cancer detection (Maurya et al. 2007). In view of these reasons, biomarkers in serum have an advantage for early diagnosis compared to any other current screening methods and these biomarkers would be able to detect tumors of size smaller than a few millimeters.

In this study, we obtained serum protein mass spectra from breast cancer patients and controls using SELDI-TOF-MS. Based on the serum proteomic profiles, we constructed a classification model to discriminate breast cancer patients from non-cancer controls. One of the challenges in the analysis of SELDI-TOF-MS-generated data is to reduce the false protein peaks, in which the discriminatory power is due to random variation (Somorjai et al. 2003). To solve this problem, in the data processing of this experiment we eliminated noise by discrete wavelength, identified mass–charge peaks of specimens using the method of local extremum, and clustered mass–charge peaks by setting 10% as the minimum threshold. Wilcoxon rank sum test analysis assessed the relative importance of each peak in the discrimination of two kinds of specimen according to P values. Furthermore, SVM was employed in our experiment, which is a kind of classification technology proposed by Vapnik and others. In the model discrimination, the popularization, model selection, overfitting, latitude disaster, and other problems of the small specimen model have been solved successfully in SVM (Wang and Wang 2004; Matheny et al. 2007; Fang et al. 2008). The procedures included combining randomly the remarkably different mass–charge peaks and inputting them into SVM, screening out the markers, building the discrimination model, and then using the method of leave-one-out to assess the model by means of cross verification. By going through these procedures mentioned above and combining many methods to process the data, the popularization of the model building and the accuracy of the prediction were ensured. The classification model could discriminate patients with breast cancer from non-cancer controls with a sensitivity of 96.45% and a specificity of 94.87% in the blind-testing set. The down-regulated candidate protein biomarker was identified as apolipoprotein C-I (6,630 Da). Another two up-regulated candidate protein biomarkers (8,139 and 8,942 Da) were identified as C-terminal-truncated form of C3a and complement component C3a.

Apolipoproteins (APO) are lipid carriers and previous studies about APO mainly focused on lipoprotein metabolism. Recently, the APO were reported to regulate many cellular functions. For example, the protein kinase Akt can be elicited by APO C-I, which in turn promotes growth factor-mediated cell survival and blocks apoptosis (Song et al. 2005). In this study, the APO C-I was down-regulated in serum of breast cancer patients, which indicated that APO C-I might be related to breast cancer. Thus, besides the function of APO C-I in lipid metabolism, additional function of APO C-I in cancerogenesis may also exist. However, the mechanism why APO C-I was degraded in breast cancer is not very clear, and further research is required.

Complement components play the important role of mediating inflammation and regulating immune response; complement 3, which is composed of alpha and beta chains, is the most abundant complement in serum. Complement 3 convertase could cleave C3 at the residue of Arg726-Ser727 into two parts: C3b (Mr 176,000 Da) and C3a (Mr 9,000 Da) (Sahu and Lambris 2001). C3a was reported as an inflammatory mediator of innate immune response (Markiewski et al. 2004); this indicated that C3a might to be a inflammation biomarker. C3a was found up-regulated in the ascitic fluids of ovarian cancer patients (Bjorge et al. 2005). Lee (Lee et al. 2006) found that C3a is elevated in patients with chronic hepatitis C and HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma.

In summary, we have identified a set of protein peaks that could discriminate breast cancer from non-cancer controls. From the protein peaks specific for breast cancer disease, we identified apolipoprotein C-I, C-terminal-truncated form of C3a and complement component C3a as potential proteomic biomarkers of breast cancer. Further studies with larger sample sizes will be needed to verify the specific protein markers. An efficient strategy, composed of SELDI-TOF-MS analysis, HPLC purification, MALDI-TOF-MS trace and LC-MS/MS identification has been proved very successful.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30772273). All authors wish to thank Dr. Liwei Mi and Dr. Shutang Wen for the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Agyei Frempong MT, Darko E, Addai BW (2008) The use of carbohydrate antigen (CA) 15-3 as a tumor marker in detecting breast cancer. Pak J Biol Sci 11:1945–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluco C, Petricoin EF, Mammano E, Facchiano F, Ross-Rucker S, Nitti D, Di Maggio C, Liu C, Lise M, Liotta LA, Whiteley G (2007) Serum proteomic analysis identifies a highly sensitive and specific discriminatory pattern in stage 1 breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 14:2470–2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorge L, Hakulinen J, Vintermyr OK, Jarva H, Jensen TS, Iversen OE, Meri S (2005) Ascitic complement system in ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 92:895–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherel P, Hagay C, Benaim B, De Maulmont C, Engerand S, Langer A, Talma V (2008) Mammographic evaluation of dense breasts: techniques and limits. J Radiol 89:1156–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gelder R, van As E, Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Bartels CC, Boer R, Draisma G, de Koning HJ (2008) Breast cancer screening: evidence for false reassurance? Int J Cancer 123:680–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Warren R, Warsi I, Day N, Thompson D, Brady M, Tromans C, Highnam R, Easton D (2008) Evaluating the effectiveness of using standard mammogram form to predict breast cancer risk: case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:1074–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Dong Y, Williams TD, Lushington GH (2008) Feature selection in validating mass spectrometry database search results. J Bioinform Comput Biol 6:223–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabiec M, Nowicki P, Walentowicz M, Grezlikowska U, Mierzwa T, Chmielewska W (2005) Role of Ca-125 in the differential diagnosis of adnexal mass in breast cancer patients. Ginekol Pol 76:371–376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansh SM, Pitteri SJ, Faca VM (2008) Mining the plasma proteome for cancer biomarkers. Nature 452:571–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Zhang SZ, Yu JK, Liu J, Zheng S (2005a) SELDI-TOF-MS: the proteomics and bioinformatics approaches in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Breast 14:250–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Zhang SZ, Yu JK, Liu J, Zheng S, Hu X (2005b) Diagnostic application of serum protein pattern and artificial neural network software in breast cancer. Ai Zheng 24:67–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundt S, Haug U, Brenner H (2007) Blood markers for early detection of colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16:1935–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ (2008) Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 58:71–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroman NT, Grinsted P, Nielsen NS (2007) Symptoms and diagnostic work-up in breast cancer. Ugeskr Laeger 169:2980–2981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laronga C, Becker S, Watson P, Gregory B, Cazares L, Lynch H, Perry RR, Wright GL Jr, Drake RR, Semmes OJ (2003) SELDI-TOF serum profiling for prognostic and diagnostic classification of breast cancers. Dis Markers 19:229–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IN, Chen CH, Sheu JC, Lee HS, Huang GT, Chen DS, Yu CY, Wen CL, Lu FJ, Chow LP (2006) Identification of complement C3a as a candidate biomarker in human chronic hepatitis C and HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma using a proteomics approach. Proteomics 6:2865–2873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang Z, Rosenzweig J, Wang YY, Chan DW (2002) Proteomics and bioinformatics approaches for identification of serum biomarkers to detect breast cancer. Clin Chem 48:1296–1304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Cao L, Yu J, Que R, Jiang W, Zhou Y, Zhu L (2008) Diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma using Protein Chip technology. Pancreatology 9:127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Qian JH, Yu JK, Zheng S, Xie X, Lu WG (2008) Discovery of altered protein profiles in epithelial ovarian carcinogenesis by SELDI mass spectrometry. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 29:233–238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markiewski MM, Mastellos D, Tudoran R, De Angelis RA, Strey CW, Franchini S, Wetsel RA, Erdei A, Lambris JD (2004) C3a and C3b activation products of the third component of complement (C3) are critical for normal liver recovery after toxic injury. J Immunol 173:747–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny ME, Resnic FS, Arora N, Ohno-Machado L (2007) Effects of SVM parameter optimization on discrimination and calibration for post-procedural PCI mortality. J Biomed Inform 40:688–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya P, Meleady P, Dowling P, Clynes M (2007) Proteomic approaches for serum biomarker discovery in cancer. Anticancer Res 27:1247–1255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo M, Rivas-Ruiz F, Guzman-Soler MC, Labajos C (2008) Monitoring indicators of health care quality by means of a hospital register of tumours. J Eval Clin Pract 14:1026–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A, Lambris JD (2001) Structure and biology of complement protein C3, a connecting link between innate and acquired immunity. Immunol Rev 180:35–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skytt A, Thysell E, Stattin P, Stenman UH, Antti H, Wikstrom P (2007) SELDI-TOF MS versus prostate specific antigen analysis of prospective plasma samples in a nested case-control study of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer 121:615–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somorjai RL, Dolenko B, Baumgartner R (2003) Class prediction and discovery using gene microarray and proteomics mass spectroscopy data: curses, caveats, cautions. Bioinformatics 19:1484–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Ouyang G, Bao S (2005) The activation of Akt/PKB signaling pathway and cell survival. J Cell Mol Med 9:59–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomosugi N (2004) Discovery of disease biomarkers by ProteinChip system; clinical proteomics as noninvasive diagnostic tool. Rinsho Byori 52:973–979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XD, Wang JQ (2004) A survey on support vector machines training and testing algorithms. Comput Eng Appl 13:75–79 [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang X, Ge X, Guo H, Xiong G, Zhu Y (2008) Proteomic studies of early-stage and advanced ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 111:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Luo RC (2005) Diagnostic value of combined detection of TPS, CA153 and CEA in breast cancer. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao 25:1293–1298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Michael CW (2007) WT1, monoclonal CEA, TTF1, and CA125 antibodies in the differential diagnosis of lung, breast, and ovarian adenocarcinomas in serous effusions. Diagn Cytopathol 35:370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]