Abstract

The glycine cleavage complex (GCV) is a potential source of the one carbon donor 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH2-THF) in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. One carbon (C1) donor units are necessary for amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis, and for the initiation of mitochondrial and plastid translation. In other organisms, GCV activity is closely coordinated with the activity of serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) enzymes. P. falciparum contains cytosolic and mitochondrial SHMT isoforms, and thus, the subcellular location of the GCV is an important indicator of its role in malaria metabolism. To determine the subcellular localization of the GCV, we used a modified version of the published method for mycobacteriophage integrase-mediated recombination in P. falciparum to generate cell lines containing one of the component proteins of the GCV, the H-protein, fused to GFP. Here, we demonstrate that this modification results in rapid generation of chromosomally integrated transgenic parasites, and we show that the H-protein localizes to the mitochondrion.

Summary

The Bxb1 integrase system was used to localize the Plasmodium falciparum H-protein to the mitochondrion. Modifications to the transfection method resulted in decreased selection times.

Keywords: Malaria, H-protein, glycine cleavage, Bxb1 integrase, mitochondrion, Plasmodium falciparum

The glycine cleavage complex (GCV) catalyzes the reversible oxidative decarboxylation of glycine, producing CO2, NH3, and a methylene group which is transferred to tetrahydrofolate (THF) to form the one carbon (C1) donor 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH2-THF). C1 donor groups are required for amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis, and for the formylation of methionine to initiate protein synthesis in plastids and mitochondria. Because the GCV reaction is reversible, it can also consume 5,10-CH2-THF for the biosynthesis of glycine. Glycine is a substrate for numerous biosynthetic pathways, including the production of γ-aminolevulinic acid (γ-ALA) in the first step of heme biosynthesis.

The GCV consists of four loosely associated proteins, known as the P (EC 1.4.4.2), H, T (EC 2.1.2.10), and L (EC 1.8.1.4) protein [1, reviewed in 2]. The H-protein subunit does not have enzymatic activity, but is modified with a lipoic acid cofactor that covalently binds to reaction intermediates and shuttles them between the active sites of other components of the complex. In the first step of the glycine cleavage reaction, the P-protein decarboxylates glycine and attaches the methylamine group to the lipoic acid cofactor on the H-protein [3]. The T-protein then transfers the methylene group to tetrahydrofolate, forming 5,10-CH2-THF and releasing NH3 [4–5]. The L-protein, a lipoamide dehydrogenase, re-oxidizes dihydrolipoic acid to lipoic acid in a NAD+-dependent reaction [GCV reactions reviewed in 2].

In eukaryotic cells such as plants and yeast, the GCV resides in the mitochondria, as does the enzyme serine hydroxymethyl transferase (SHMT), which reversibly catabolizes serine to form glycine and 5,10-CH2-THF [6]. These organisms contain only one GCV but have multiple SHMT isoforms. In animal cells, isoforms of the SHMT are found in the cytosol (cSHMT) and the mitochondria (mSHMT), and plants have a plastid-resident SHMT (pSHMT) in addition to cSHMT and mSHMT [6]. The existence of multiple isoforms of SHMT in these cells reflects the requirement for one-carbon folates in the mitochondria, plastid, and cytosol. Trafficking of charged (polyglutamyl) folate derivatives between subcellular compartments is limited. Thus, three molecules that can be catabolized to derive C1 units: serine, glycine, and formate, shuttle C1 units between organelles and the cytosol.

The role of the GCV is intimately connected to the activity of the SHMTs in plants and yeast. In non-photosynthesizing plant tissues the GCV is essential, as it functions to replenish the cytoplasmic serine pool which is used by the cSHMT to generate cytoplasmic C1 donors [7–8]. In this process, glycine produced by cSHMT is trafficked to the mitochondrion and catabolized by the GCV, yielding 5,10-CH2-THF. The methylene carbon from 5,10-CH2-THF is then shuttled back to the cytosol in the form of a serine molecule generated by mSHMT [8]. Thus, the net reaction catalyzed in the mitochondrion is:

The resulting serine is used by cSHMT to generate cytosolic 5,10-CH2-THF. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the GCV plays a similar role, except that it is non-essential when glycine is not the sole source of nitrogen and carbon, and the complex appears to function reversibly, catabolizing glycine or synthesizing it depending on the metabolic state of the cell [9].

Candidate genes encoding three of the four GCV proteins were found in the genome of Plasmodium falciparum (T=PF13_0345, L=PFL1550w, H= PF11_0339); however, no homolog of the P-protein has been identified [10]. Similarly, among the apicomplexan parasites Toxoplasma gondii, Theileria parva, and Babesia bovis, genes encoding putative T, L, and H-proteins, but not P-protein homologs, have been identified [11]. This apparently incomplete GCV is not unique to apicomplexa; the presence of the H and L-proteins, with the P and/or T-proteins absent, is also found in the protozoan T. vaginalis and many bacterial species [12].

Like other eukaryotes, P. falciparum encodes multiple SHMT isoforms that may work cooperatively with the GCV in C1 metabolism. A functional cSHMT (PFL1720w) has been characterized [13], and a putative mSHMT (PF14_0534) which does not appear to contain the functional residues typically found in SHMT enzymes has been described [10]. No plastid SHMT has been identified in malaria parasites. The conspicuous absence of a complete GCV and the divergence of conserved residues in the P. falciparum mSHMT could indicate that the GCV and mSHMT genes do not encode functional, expressed proteins. Conversely, these differences may be clues that apicomplexans have developed novel approaches to C1 and glycine metabolism, or that some subunits of the GCV have noncanonical roles. The mSHMT has not been characterized, however, pure recombinant P. falciparum H-protein has been shown to be lipoylated in vitro by a mitochondrial lipoate ligase (PF13_0083) [14]. Additionally, we previously showed the presence of lipoylated H-protein in P. falciparum erythrocytic stages by western blot and in radiolabel incorporation experiments [14], suggesting that the GCV could function during the blood stages. No components of the GCV have been experimentally localized.

Here, we describe a modified approach to the site-specific mycobacteriophage integration system described by Nkrumah et al. [15], which we used to generate integrated cell lines expressing H-protein-GFP (H-proteinDd2) and localize the H-protein to the P. falciparum mitochondrion. Our initial efforts using the published method were hampered by selection times for transgenic cell lines in excess of three to four weeks. We therefore made two alterations to the published protocol that accelerate the selection of integrated, transgenic parasites: elimination of drug selection with G418, and adoption of a preloading transfection method.

The site-specific integration approach requires two plasmids, called pINT and pLN, as well as a parasite strain that contains an attB integration site (such as Dd2attB). The plasmid pINT encodes the mycobacteriophage Bxb1 integrase and confers resistance to G418 (Geneticin), and pLN encodes the transgene, contains an attP site, and confers resistance to blasticidin [15]. In a dually transfected parasite, the integrase expressed from pINT catalyzes the crossover of the pLN attP site with the genomic attB site, resulting in the integration of pLN into the genome. Consequently, all daughter parasites of the integrant are blasticidin resistant; however, G418 resistance depends on the segregation of pINT plasmids into daughter cells during schizogony. We hypothesized that maintenance of pINT is not necessary if integration of pLN occurs rapidly, and that the rate of integration depends heavily on the number of individual cells containing both plasmids. We therefore selected with blasticidin alone, and, in order to maximize the number of healthy, dually transfected cells, we relied on spontaneous uptake of plasmids from red blood cells transfected with plasmid DNA (pre-loading) instead of direct electroporation of infected red blood cells. Using this approach, we found that we could quickly and reproducibly generate transgenic strains. When we compared the selection times between the modified and published methods in head-to-head experiments, we found that cells were generated several weeks sooner with the modified method.

Our transfection experiments were performed with pLN plasmid containing the P. falciparum H-protein. The gene encoding the H-protein was amplified by PCR from the plasmid pMA007 [14], using TurboPfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and the H-protein primers listed in the Supplementary Information. The PCR product and the vector pLN-ENR-GFP [15] (obtained from the MR4) were digested with AvrII and BsiWI (New England Biolabs) and ligated together with Quick Ligase (New England Biolabs). E. coli transformed with the ligation product were selected on LB plates containing 100 μg/ml carbenicillin. The gene sequence of the resulting plasmid, pMA013, was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

One hundred twenty microliters of packed, uninfected red blood cells were electroporated (BioRad Gene Pulser, 0.2 cm cuvette, 2.5 kV, 950 μF, infinite resistance) with 65 μg of each of the plasmids pMA013 and pINT and adjusted to 1% hematocrit in complete medium. Between 2–2.5 ml of Dd2attB strain parasites at 1% hematocrit and 15–25% parasitemia were added to the transfected red blood cells. The medium was changed every 24 hours, and at 48 hours transgenic cells were selected with 2.5 μg/ml blasticidin. The culture was checked for transgenic parasites 10 days after drug selection, and every two days thereafter. We considered a culture to be positive when one or more asexual stage parasites were detected in ten or fewer frames of densely packed (approximately 300 cells per frame) red blood cells on a giemsa stained slide (.03% parasitemia). In three experiments, H-proteinDd2 parasites were observed on days 10, 12, and 12 (Table 1), cultures reached 1% parasitemia on or before day 20, and all cell lines were integrated and expressed the transgene.

Table 1.

Comparison of dual transfection strategies.

| 2.5 μg/ml Blasticidin | 2.5 μg/ml Blasticidin + 125 μg/ml G418 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | Transfection method | Days to detection | Average days to detection | Days to detection | Average days to detection |

| H-protein-pLN, pINT | pre-loading | 10, 12, 12 | 11 | 10, 18, 20 | 16 |

| H-protein-pLN, pINT-R20 | pre-loading | 10, 10, 10 | 10 | 10, 12, 12 | 11 |

| H-protein-pLN, pINT | direct electroporation | 20, 28, 34 | 27 | 34, 34, 42 | 37 |

Dd2attB parasites were transfected with 65 μg of pMA013 and 65 μg of either pINT or pINT-R20 by pre-loading or direct electroporation. The time to detect parasites in ten frames of densely packed red blood cells (approximately 1/3000 red blood cells or .03% parasitemia) was recorded.

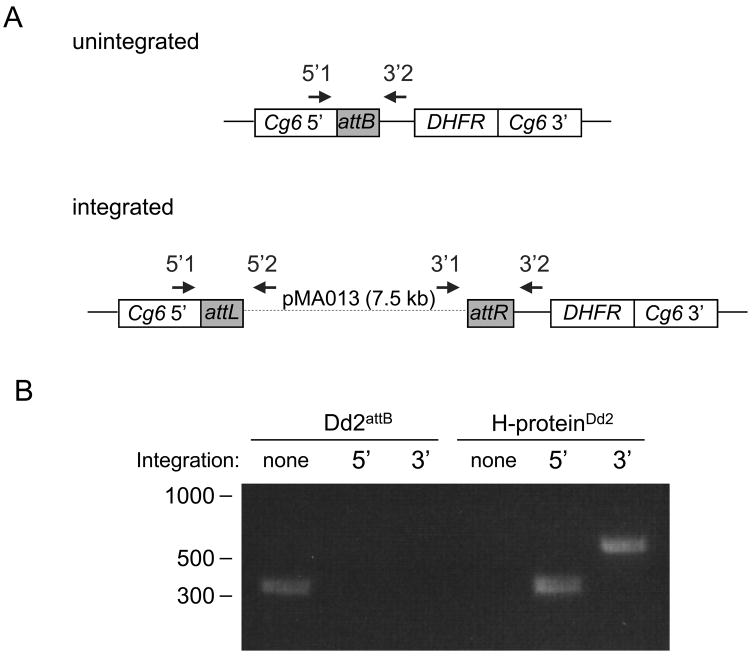

A major concern of selection with blasticidin alone was whether we would select for parasites containing episomal, as opposed to integrated, pMA013. We characterized the H-proteinDd2 cell line by PCR analysis of the integration site using primers that flanked the 5’ and 3’ integration sites. The 5’ and 3’ integration sites were amplified from H-proteinDd2 genomic DNA, demonstrating that pMA013 integrated at the attB locus (Figure 1). The unintegrated attB locus was detected in the parental Dd2attB cell line but not in the H-proteinDd2 cell line (Figure 1), demonstrating that this method does not produce a subpopulation of unintegrated parasites containing episomal pMA013. Plasmid rescue performed on genomic DNA extracted from parasites harvested two to three weeks after beginning drug selection also did not recover any plasmid. Taken together, these results confirm that integration of pMA013 must have occurred rapidly (prior to the loss of the pINT plasmid), followed by gradual loss of any episomally maintained pMA013 plasmid.

Figure 1. Integration of pMA013 at the attB locus.

(A) Schematic of primer annealing sites at the unintegrated attB locus and at the integrated locus, in which the attP site on pMA013 combines with the attB site to yield attL and attR sequences. (B) Genomic DNA was extracted from the parental Dd2attB parasites and from the transgenic cell line H-proteinDd2 and analyzed for the presence of the attB (no integration), attL (5′ integration), and attR (3′ integration) sites.

We also developed a strategy to recover integrated plasmid from transgenic cell lines for diagnostic restriction digests and sequencing. Nkrumah and coworkers used the endonuclease EcoRI to insert tandem 50 base attP sites into a unique site in the pLN plasmid [15]. After integration, EcoRI can be used to excise pLN from parasite genomic DNA. Fifty nanograms of H-proteinDd2 genomic DNA were digested with three units of EcoRI (New England Biolabs) in a 10 μl reaction buffered with New England Biolabs Buffer 2. After heat inactivation of EcoRI for 20 minutes at 65°C, the reaction mixture containing the digested gDNA was diluted with 2x Quick Ligase buffer and treated with Quick Ligase enzyme (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ligation reaction was transformed into Top10 strain E. coli, and the recovered plasmid was selected on LB plates containing 100 μg/ml carbenicillin. Plasmid pMA013 (lacking the attP recombination sites) was recovered using this method and was used to verify the sequence of the transgene. This method also recovers a 2966 base fragment of the pCG6-attB plasmid originally used to introduce the attB site into the CG6 locus of Dd2 strain parasites. This plasmid contained an attR site which could only be generated by integration of the pLN plasmid (see Supplementary Information).

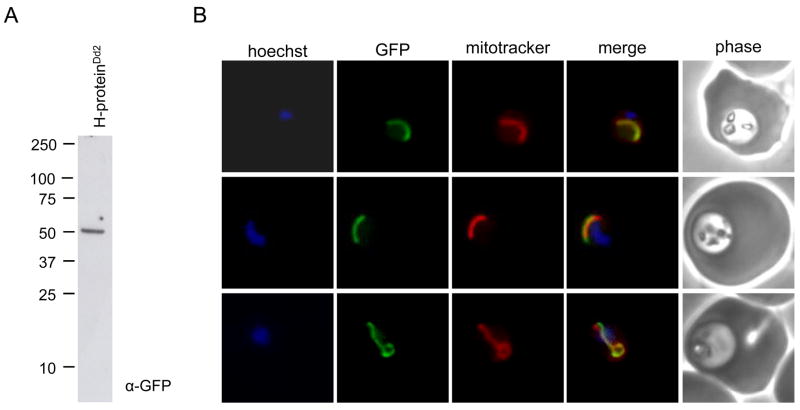

After successful generation of the H-proteinDd2 cell line, we confirmed that a protein of the expected size was expressed by western blot of H-proteinDd2 whole cell lysate with antibody specific for GFP (Figure 2A). We then determined the subcellular location of the H-protein by co-localization of GFP fluorescence with the mitochondrial marker mitotracker CMX-Ros (Invitrogen) in live cells. The H-protein is localized exclusively to the mitochondrion (Figure 2B), indicating that this component of the glycine cleavage pathway resides in this organelle. This and our previously published results [14] confirm that the holo-H-protein is present in the P. falciparum mitochondrion, suggesting that it may have a functional role in this organelle.

Figure 2. Expression and localization of the H-protein in H-proteinDd2 cells.

(A) Expression of H-protein-GFP. H-proteinDd2 parasites were isolated from red blood cells by lysis with 0.2% saponin for 3 minutes and the reaction was quenched with ice cold PBS. The parasite pellet was washed twice in 10 ml of ice cold PBS. Parasites were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer and lysed by three cycles of heating at 95°C followed by vortexing. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transblotted onto nitrocellulose. H-protein-GFP was detected with monoclonal antibody specific for GFP (1:1000, Clonetech). (B) Co-localization of GFP fluorescence from H-proteinDd2 cells with mitotracker and Hoechst dyes. Live cells from the H-proteinDd2 cell line were incubated with 100 nM mitotracker CMX-Ros (Invitrogen) and 1 μg/ml Hoechst stain for 20 minutes at 37°C followed by 2 washout periods in complete media for five minutes. Cells were imaged on a Nikon Eclipse E800 epifluorescent microscope, and the images were processed with ImageJ software.

In order to evaluate the potential advantages of the described alterations in the dual transfection protocol, we compared, in triplicate, pre-loading and direct electroporation techniques and selection with blasticidin alone versus blasticidin and G418. Pre-loading experiments were conducted as previously described, and experiments under double drug selection were treated with 2.5 μg/ml blasticidin (Sigma) and 125 μg/ml G418 (Roche). Direct electroporation transfections used 200 μl of red blood cells from a Dd2attB culture containing mostly ring stage parasites at 5–6% parasitemia, and were performed according to the electroporation parameters described above. For these experiments, transgenic cells were selected approximately 12 hours after electroporation. As previously described, cultures were first checked for transgenic parasites 10 days after drug selection, and then every other day.

The average time for generation of transgenic cells using pre-loading and selection with blasticidin alone was 11 days, an average of five days faster than pre-loading followed by selection with both drugs. By comparison, direct electroporation followed by selection with blasticidin produced cells in an average of 27 days, more than two weeks longer than the preloading experiments, and addition of G418 delayed the appearance of transgenic cells by an additional 10 days. Together, these results demonstrate that the selection time can be significantly decreased by using a pre-loading transfection method, and that removal of G418 selection further accelerates the appearance of transgenic parasites.

We were curious as to whether the absence of selection for pINT in the initial rounds of replication following transfection resulted in “missed” integration opportunities. To address this, we modified pINT to contain a Rep20 repeat sequence for better plasmid retention during parasite division [16]. Primers R1 and R2 (Supplementary Information) were used to amplify the 510 nucleotide Rep20 repeat from pTGPI-GFP [17] with flanking HindIII restriction sites. The resulting amplicon and pINT, which contains a unique HindIII site, were digested with HindIII and ligated together. A clone containing two tandem Rep20 inserts (pINT-R20) was isolated and sequence verified.

We conducted a series of transfections using the pre-loading method and 65 μg of each of the plasmids pMA013 and pINT-R20. As expected, improved segregation of the pINT-R20 plasmid accelerated the appearance of parasites (as compared to the original pINT) when selection was conducted with both blasticidin and G418 (Table 1). However, when blasticidin alone was used for selection, pINT-R20 and pINT behaved similarly (Table 1). Thus, any additional integration events associated with improved retention of pINT-R20 did not significantly decrease selection times. These experiments show that integration occurs rapidly, and that prolonging the presence of pINT with drug selection or the Rep20 sequence does not significantly accelerate the generation of transgenic parasites.

Here, we have employed a variation on the Bxb1-integrase mediated site-specific recombination system developed for use in P. falciparum by Nkrumah et al. [15] which resulted in the swift generation of the cell line H-proteinDd2. Selection only for the plasmid containing the transgene, instead of selection for this plasmid and the integrase-containing plasmid, results in the rapid generation of integrated transgenic cell lines without losing the phenotypic and genetic homogeneity observed by Nkrumah et al. The cell line resulting from this validation was then used to localize the H-protein to the mitochondrion, showing that the GCV complex resides in the P. falciparum mitochondrion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Muhle, Louis Nkrumah, and David Fidock for helpful conversations concerning the use of the Bxb1 integrase system. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI065853, STP), the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute and the Bloomberg Family Foundation (MDS and STP).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Motokawa Y, Kikuchi G. Glycine metabolism by rat liver mitochondria. Isolation and some properties of the protein-bound intermediate of the reversible glycine cleavage reaction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974;164:634–40. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douce R, Bourguignon J, Neuburger M, Rebeille F. The glycine decarboxylase system: a fascinating complex. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:167–76. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujiwara K, Motokawa Y. Mechanism of the glycine cleavage reaction. Steady state kinetic studies of the P-protein-catalyzed reaction. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:8156–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujiwara K, Okamura-Ikeda K, Ohmura Y, Motokawa Y. Mechanism of the glycine cleavage reaction: retention of C-2 hydrogens of glycine on the intermediate attached to H-protein and evidence for the inability of serine hydroxymethyltransferase to catalyze the glycine decarboxylation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;251:121–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamura-Ikeda K, Fujiwara K, Motokawa Y. Purification and characterization of chicken liver T-protein, a component of the glycine cleavage system. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen KE, MacKenzie RE. Mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism is adapted to the specific needs of yeast, plants and mammals. Bioessays. 2006;28:595–605. doi: 10.1002/bies.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engel N, van den Daele K, Kolukisaoglu U, et al. Deletion of glycine decarboxylase in Arabidopsis is lethal under nonphotorespiratory conditions. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1328–35. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.099317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouillon JM, Aubert S, Bourguignon J, Gout E, Douce R, Rebeille F. Glycine and serine catabolism in non-photosynthetic higher plant cells: their role in C1 metabolism. Plant J. 1999;20:197–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piper MD, Hong SP, Ball GE, Dawes IW. Regulation of the balance of one-carbon metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30987–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salcedo E, Sims PF, Hyde JE. A glycine-cleavage complex as part of the folate one-carbon metabolism of Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:406–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeber F, Limenitakis J, Soldati-Favre D. Apicomplexan mitochondrial metabolism: a story of gains, losses and retentions. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:468–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spalding MD, Prigge ST. Lipoic acid metabolism in microbial pathogens. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2010 doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00008-10. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alfadhli S, Rathod PK. Gene organization of a Plasmodium falciparum serine hydroxymethyltransferase and its functional expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;110:283–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allary M, Lu JZ, Zhu L, Prigge ST. Scavenging of the cofactor lipoate is essential for the survival of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1331–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nkrumah LJ, Muhle RA, Moura PA, et al. Efficient site-specific integration in Plasmodium falciparum chromosomes mediated by mycobacteriophage Bxb1 integrase. Nat Methods. 2006;3:615–21. doi: 10.1038/nmeth904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Donnell RA, Freitas-Junior LH, Preiser PR, et al. A genetic screen for improved plasmid segregation reveals a role for Rep20 in the interaction of Plasmodium falciparum chromosomes. Embo J. 2002;21:1231–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meissner M, Krejany E, Gilson PR, de Koning-Ward TF, Soldati D, Crabb BS. Tetracycline analogue-regulated transgene expression in Plasmodium falciparum blood stages using Toxoplasma gondii transactivators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2980–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500112102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.