Abstract

Allergen-specific immunotherapy is recognized as a highly effective practice in the treatment of patients with severe allergic rhinitis and/or asthma and is recommended by World Health Organization as an integrated part of allergy management strategy. Several studies have shown that allergen-specific immunotherapy, based on the administration of increasing doses of allergen, achieves a hyposensitization and reduces both early and late responses occurring during the natural exposure to the allergen itself. This is the unique antigen-specific immunomodulatory treatment in current use for human diseases. Successful immunotherapy is associated with reductions in symptoms and medication scores and improved quality of life. After interruption it usually confers long-term remission of symptoms and prevents the onset of new sensitizations in children up to a number of years. Subcutaneous immunotherapy usually suppresses the allergen-induced late response in target organs, likely due to the reduction of the infiltration of T cells, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells and neutrophils. In addition to the reduction of cells of allergic inflammation, immunotherapy also decreases inflammatory mediators at the site of allergen exposure. This review provides an update on the immunological T cell responses induced by conventional subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy, and gives a unifying view to reconciling the old dualism between immunoredirecting and immunoregulating mechanisms.

Keywords: allergen-specific immunotherapy, allergy, cytokines, T effector cells, regulatory T cells

Introduction

Allergen-specific immunotherapy is recognized as a highly effective practice in the treatment of patients with severe allergic rhinitis and/or asthma and is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an integrated part of allergy management strategy [1–3]. Several studies have shown that subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT), based on the administration of increasing doses of allergen, achieves a hyposensitization and reduces both early and late responses occurring during the natural exposure to the allergen itself. SCIT is the unique antigen-specific immunomodulatory treatment in current use for human diseases. It is employed successfully to treat patients with sensitivity to a wide range of allergens and well-documented immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated diseases, such as seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis, allergic asthma and insect venom severe reactions. Successful SCIT is associated with reductions in symptoms and medication scores and improved quality of life [4]. After interruption, SCIT usually confers long-term remission of symptoms [5] and prevents the onset of new sensitizations in children up to a number of years [6]. SCIT usually suppresses the allergen-induced late response [7,8] in the lung, nose and skin, due probably to the reduction of the infiltration of T cells, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells and neutrophils [9,10]. In addition to the reduction of cells of allergic inflammation, SCIT also decreases inflammatory mediators at the site of allergen exposure [10].

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) was introduced during the 1980s as an alternative route of immunotherapy to improve safety. Its efficacy has been shown by some meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials in adults with respiratory allergy [11–14]. There is a general consensus that SCIT is more effective than SLIT, while the latter is associated with fewer side effects [11–14]. WHO (1998) and Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA 2001) documents indicate SLIT as a valid alternative to SCIT and its use is justified in adults [15–17]. In contrast to evidence in adults, SLIT efficacy in children is less convincing, as subgroup analyses for seasonal and perennial allergens provide controversial data [11,18], varying from moderate to no effect [19]. Promising evidence of efficacy for SLIT on patients (adults and children) with perennial allergy has been shown by a very recent meta-analysis [20], even though more data are needed, possibly obtained from large-population-based high quality studies and confirmed by objective outcomes.

This review provides an update on the immunological T cell responses induced by conventional SCIT and SLIT, and gives a unifying view to reconciling the old dualism between immunoredirecting and immunoregulating mechanisms.

Pathogenesis of allergic response

The role of the T helper type 2 (Th2) cell-mediated immune response against ‘innocuous’ environmental antigens (allergens) in the immunopathogenesis of allergic atopy is well established. In allergic individuals priming of allergen-specific CD4+ Th2 cells by antigen-presenting cells (APC) results in the production of Th2 cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13, which are responsible for the initiation, maintenance and amplification of human allergic inflammation. This experimental evidence includes the identification of cytokines, chemokines and transcription factors connected with Th2 responses in target organs of allergic subjects [21,22].

The development of allergen-specific Th2 cells in genetically defined individuals has been revisited recently. Asthma susceptibility genes have been described to be associated with allergy per se or with the ability to increase airway bronchial hyperractivity (AHR) [23]. The products of the first group of genes are expressed mainly by skin, intestinal and lung epithelial cells, influencing their way to respond to inflammatory stimuli. Other susceptibility genes regulate the response of cells of innate immunity to allergens [23]. Moreover, it has emerged that some of the clinically relevant allergens modify the function of airway epithelial cells or of innate or adaptive immune cells. Among the allergens listed in public-domain databases (e.g. Allergome of the Structural Database of Allergenic Proteins), more than 80 different allergens exert serine and cysteine protease activities, increase vascular permeability through the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or trigger Toll-like receptors (TLRs) directly in some relevant cells [24–26]. There is a general consensus that sensitization and progression to respiratory allergy is influenced by a cross-talk among barrier epithelium, mucosal dendritic cells (DC) and other cells of innate and adaptive immunity. Allergen-driven protease-activated receptors (PARs) or TLRs signalling in epithelial cells induce nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation and secretion of cytokines essential for Th2 (IL-25, thymic stromal lymphopoietin, IL-33, etc.) and Th17 [IL-1β, osteopontin, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, etc.] cell differentiation [24,27].

Type 2 cytokines have a direct effect on B cell switch to the IgE isotype and on the recruitment of a number of inflammatory cells (mainly mast cells and eosinophils), whose persistence favours the chronic evolution of inflammatory response [21,22].

The role of Th17 responses in allergic diseases has been re-examined recently regarding mainly chronic evolution and airway remodelling. Several data in the experimental model provide evidence that IL-17 in the lung (produced by CD4+ T and NKT cells, alveolar macrophages and epithelium) plays a pathogenetic role in promoting neutrophil influx, the production of pro-fibrotic cytokines by bronchial fibroblasts and the release of eosinophil chemoattractants by the airway muscle cells [28–30]. Furthermore, it has been reported that IL-17 mRNA and protein increased in the lung, sputum and bronchial alveolar lavage (BAL) fluids or the sera of asthmatics, and its levels correlated with the severity of airway hypersensitivity [31]. We have characterized recently a new subset of T cells in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and lung of respiratory allergic patients producing both IL-17 and IL-4. These cells, sharing the features of Th2 and Th17, increase significantly in PBMC of asthmatic individuals [32]. Due to the heterogeneity of asthmatic phenotypes with increased IL-17 levels in the sputum, it is likely that this cytokine contributes in different ways to the pathogenesis of allergic and not allergic asthma and of steroid resistance and may be considered a new marker for classification of both eosinophilic and/or neutrophilic-dominant diseases [31,33].

Certainties and controversies of T cell response during SCIT and SLIT

The decreased proliferative response of PB T cells to allergen observed usually in SCIT-treated patients is consistent with anergy and/or deletion of allergen-specific T cells [34]. It has been suggested that a high-dose tolerance explains T cell unresponsiveness, because doses given in SCIT are considerably higher than those encountered naturally. Moreover, in vitro studies have shown that proliferation of PB T cells of allergic patients decreased when high, compared to low, concentrations of allergens were used in both SCIT and SLIT regimens [35,36]. Anergy was shown in studies of SCIT for bee venoms, where the impaired T cell response to phospholipase A2 allergen was associated with no change in proliferation to recall antigens, and with increased IL-10, which is able to reduce the proliferative response [37]. Moreover, high-dose antigen can also trigger apoptosis of Th2 cells in allergen-stimulated PBMC from treated patients [38]. Finally, it is accepted generally that high doses of allergens allow efficacy to be achieved without compromising safety [35,39].

At the beginning of the 1990s, with the definition of the Th1–Th2 paradigm, initial results based on several in vitro and in vivo models concluded that SCIT skewed allergen-specific responses from Th2 to a more protective Th1 phenotype, a mechanism known as immunodeviation [9,40]. Others have been unable to reproduce these findings, and reported no changes in proliferative responses or cytokine production [41], due probably to variations of SCIT regimens and in vitro methodology. Nevertheless, Th1-redirection induced by SCIT with allergen extracts or peptides continues to be reported in more recent studies [42–44].

Because alterations in circulating T cells do not reflect local events in target organs, some studies have evaluated Th1 redirection induced by SCIT in respiratory mucosa. In patients treated with SCIT, T cells expressing IFN-γ mRNA were increased in the nasal mucosa after pollen challenge [41,45]. An inverse correlation between the proportions of IFN-γ+ T cells and the symptoms and medications scores during the pollen exposure was also shown. In other reports in nasal biopsies and in nasal fluid of SCIT-treated patients the increase of IFN-γ and the concomitant decrease of IL-5 and IL-9 during the pollen season were shown [46–48]. SCIT has also been proved to inhibit the seasonal increase of circulating basophils and type 2 cytokines [49].

SCIT generally inhibits allergen-induced late cutaneous responses and this correlates with increased IL-12 mRNAs expression in skin macrophages [50]. In this study IL-12 expression correlates directly with IFN-γ and, inversely, with IL-4 [50]. Accordingly, the increase of IL-12-producing monocytes and IFN-γ-producing NK and T cells was also reported [51,52]. Even though few data are available at present on the effect of SCIT on the IL-23/IL-17 axis, it is likely that the local excess of IL-12 induced by the treatment can skew Th17 to Th1 responses, as we have shown recently in in vitro models [28]. In conclusion, several reports provide evidence that immunodeviation may occur at the local and systemic levels.

After the discovery of regulatory T cells (Treg), the importance of their increased activity (immunosuppression) as the main or even unique explanatory mechanism for the clinical efficacy of SCIT was emphasized. Adaptive Treg cells are a highly heterogeneous family, initially including type 3 Th (Th3) cells, T regulatory 1 (Tr1) cells, and CD4+CD25+forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)+ T cells. However, some other unsuspected T cell subsets have been shown recently to display regulatory activity [53,54]. Adaptive Treg cells originate in peripheral lymph nodes during the priming of effector T cells, where they acquire the suppressive machinery upon particular conditions of APC stimulation. Their suppressor activity is mediated by the regulatory cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-β and IL-35, but the involvement of mechanisms necessitating cell-to-cell contact has also been reported [55].

During pollen exposure CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from grass-sensitive patients have been shown to be impaired in suppressing IL-13 and IL-5 production compared to those from healthy controls [56]. While allergen-specific Th2 cells occurred at a higher frequency in allergic subjects, in healthy individuals Treg cells predominate [57]. However, our group demonstrated recently that allergen (Der p 1)-specific CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells expanded from the peripheral blood of healthy donors were similar phenotypically and functionally to those derived from house dust mite (HDM)-allergic donors. Concerns have arisen regarding the role of these cells in suppressing the Th2 response in non-allergic individuals [58]. Even though the suppression of allergen-specific responses by Treg cells may represent the normal response to these molecules [59], some recent reports show that allergen-specific T cells in newborns can also exert a Th1 profile. The ability to secrete IL-12 (but not IL-10) by cord blood mononuclear cells is associated with variations in allergen-specific responses in neonatal and postnatal periods [60]. By examining more than 900 newborns this study showed that allergen-specific IgE were related inversely to IFN-γ, but not IL-10, production by stimulated cord blood mononuclear cells [60]. Moreover, purified Bet v 1-specific CD4+ T cells from healthy individuals have been shown to secrete much more IFN-γ than IL-10 in response to this allergen, and interestingly the two cytokines were not co-expressed by the same cells [61]. The fact that healthy individuals possess circulating Der p 1-specific T cells exerting a Th1-polarized profile provides further support to the concept that healthy and allergic subjects show differently polarized effector T cells recognizing allergens. This hypothesis appears more plausible than the possibility that different mechanisms of homeostasis are active in the immune system [62].

Increased proportions of allergen non-specific Treg cells have been described under SCIT [63], thus supporting some role in vivo for these cells and their secreted cytokines in the mechanism of successful therapy. IL-10 inhibits major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression on DC, as well as tyrosine phosphorylation of CD28 in T cells, preventing further downstream signalling events [37]. Furthermore, IL-10 down-regulates both type 1 and type 2 cytokines (and also IL-17-related molecules) in vitro and induces anergy of effector T cells [64,65]. The up-regulation of regulatory cytokines during SCIT has been described mainly in patients treated for hymenoptera venom [37,57]. IL-10-producing T cells have also been detected in the skin biopsy after intradermal challenge in patients treated for hymenoptera venom [66], as well in nasal mucosa under SCIT for respiratory allergy [67]. Increased local Tr1 cells have been associated with elevated serum IgG4 and blocking activity for IgE-facilitated allergen presentation [68]. Treg cells have also been related to the production of TGF-β, a molecule regulating antigen presentation, expression of co-stimulatory molecules and T cell proliferation [37,57]. TGF-β is also involved in the IgA switch in humans, and increased levels of allergen-specific IgA in the sera have been associated with increased Treg cells and successful SCIT [69].

With the introduction of SLIT, studies have been focused upon the immunological alterations induced by this treatment. Sublingual allergen is captured within the oral mucosa by Langerhan's-like DC which are prone to tolerance as they express FcεRI, produce IL-10 and TGF-β and up-regulate suppressive indeolamine 2–3 acetate dioxygenase (IDO) [70,71]. Moreover, oral mucosa contains limited numbers of mast cells, thus explaining the well-established safety profile of SLIT [71]. A trial performed in HDM-sensitive children indicated that, despite similar clinical improvement, the SCIT and SLIT regimens exerted different immunological responses [36]. Some reports did not show alterations in T cell response after SLIT, while others described alterations of T cell proliferation, cytokine production and serum IgG1/IgG4 [72,73]. Even though cellular and humoral changes were more pronounced in SCIT, the immunological alterations of SLIT and its efficacy were dependent upon the doses and duration of treatment [36]. Cytokines produced by allergen-specific T cells varied according to the different phases of treatment. In two recent trials SLIT increased IL-10 or TGF-β in the first months of therapy, while it up-regulated IFN-γ or, respectively, IFN-γ/IL-10 production after 24 months of treatment [74,75]. A parallel increase of Treg cells and of IL-10 and TGF-β mRNA expression was found in a 2-year trial of SLIT for pollens in children [76]. Notably, in this study the increased IL-17 synthesis by allergen-stimulated PBMC correlated with poor effects of SLIT, while in another report the reduced IL-17 production was associated with successful therapy [77].

There is general agreement that these data, including the increased IgG4 seen with high-dose protocols and prolonged treatment, provide evidence that at least qualitatively SLIT induces similar immunoredirecting and immunoregulating alterations of SCIT [69,77,78].

Are the immunoredirection and immunoregulation induced by SCIT and SLIT two sides of the same coin?

In the last decade the mechanisms of immunodeviation and immunoregulation induced by SCIT or SLIT have usually been presented as alternative, mutually exclusive events, and often the discussion of these two paradigms has deteriorated into a sort of iconoclastic war. However, more recent data indicate that such immunological changes include the involvement of both allergen-specific Th1 and Tr1 cells and that, possibly, the supposed dualism may be considered as two sides of the same coin.

The ability of an immunodominant region of an antigen to induce IL-10 and IFN-γ was described previously for the hepatitis C virus core protein as a general homeostatic mechanism favouring the persistence of infection [79].

By using tolerogenic Fel d 1 peptides as vaccine in sensitized patients, Reefer and colleagues showed that two major epitopes of this allergen were able to induce IL-10 or IFN-γ selectively and fulfil a tolerogenic role in SCIT-treated patients or healthy subjects [80]. In a related open study using a low-dose regimen of Fel d 1 the magnitude of the cutaneous late-phase reaction paralleled the accumulation of Tr1 and Th1 cells in allergen-challenged skin sites [51]. The concept that an allergen contains epitopes with different immunoreactive potential has also been observed by our group on Par j 1 [81].

The connection between IFN-γ and IL-10 production was described initially in experimental models in which CXCL10 (and IFN-γ-producing chemokine) modulated mature DC into a tolerogenic form able to expand Treg cells in vitro [82]. Other reports indicate that chronic stimulation of DC by IFN-γ induced the production of IDO, whose metabolites decrease T cell proliferation and expand Tr1 cells [83].

In rush immunotherapy for bee venom a rapid Th2 to Th1 shift has been described, associated with a parallel increase of cells that have characteristics of both naturally or adaptive, IL-10-producing or non-producing, Treg cells. This study suggests that rush immunotherapy exerts various patterns of immune responses, the Th1 and Tr1 cells being prevalent in patients with grades I–II reactions [84].

More recently, SLIT has been shown to induce Tr1 cells in the early (1 month) phase of treatment, followed by a Th1 skewing after 1 year of therapy [74]. Some authors speculate that the predominance of different mechanisms of tolerance induction is time- and dose-dependent. Similarly, high cumulative doses of SCIT promoted the expansion of IFN-γ producing T cells, the apoptosis of Th2 cells and T cell anergy in vitro[85]. Also, in the reports stressing the increase of FoxP3+CD25+IL-10+ T cells in the nasal mucosa of SCIT-treated grass-sensitive patients or in the blood of peanut oral immunotherapy, a parallel increase of IFN-γ-producing T cells was underestimated [67,85]. Finally, the previously described trial with HDM-sensitive patients provided evidence that clinically effective SLIT was associated with suppression of allergen-specific T cell response, early (12 months) increase of TGF-β and late (24 months) up-regulation of IFN-γ and IL-10. Notably, IL-10 was found to be produced exclusively by T cells [75].

In a study evaluating the effect of SLIT on immunological response to allergen in HDM-sensitive allergic patients, we showed that upon allergen stimulation PBMC from patients treated for 6 months produced higher amounts of IL-10 and IFN-γ in vitro compared to those observed at the beginning of therapy. The co-expression of both cytokines by allergen-specific CD4+ T cells has been described in patients undergoing immunotherapy, but not before treatment [86]. The contemporary presence of IL-10 and IFN-γ in PBMC from SCIT-treated patients as well as in diseases with chronic antigen stimulation have been reported [63,87–89]. However, this was the first report in which the co-expression of IL-10 and IFN-γ by allergen-specific CD4+ T cells was described during SLIT [86].

These data suggest clearly that both immunodeviation and regulation are both elicited upon immunotherapy. IL-10 and IFN-γ are able to impair in vitro allergen-specific Th2 responses as well as down-regulate IgE-producing cells (IFN-γ) directly or switch to IgG4 subclass (IL-10), thus giving a biological rationale to the clinical efficacy of SLIT [20]. Regulatory IFN-γ/IL-10 double-positive T cells (called Th1-like Tr1 cells) have been described in mice undergoing chronic stimulation with antigens [88], and are involved in humans in the protection against certain pathogens such as leishmania, borrelia and mycobacteria [88]. Subsequent results indicated that the principal source of IL-10 in chronic human infections was CD4+CD25−FoxP3− Th1 cells [90,91]. Indeed, even though the IL-10 promoter and some putative elements are silenced in Th1 cells, the IL-10 locus is in a reversible histone deacetylase-responsive state in these cells, which can lead to its reactivation when a prolonged antigenic stimulus, a high activation state and elevated IL-12 levels are present [92]. The contemporary production of IFN-γ and IL-10 by effector T cells probably limits the collateral damage caused by exaggerated inflammation, but may reduce the efficacy of the immune response resulting in a failure to eliminate pathogens [93,94]. Notch1 triggering through different Notch ligands is the major signal to induce IL-10 production in newly developing and already established Th1 cells via a signal transduction and activator of transcription-4 (STAT4)-dependent pathway. This process also requires the presence of the cytokines IL-12 and IL-27, which favours Th1 cells to synthesize IL-10 without interfering with IFN-γ production [95]. Notably, IL-27 has been shown to induce IL-10 not only by Th1 but also Th2 and Th17 effector cells [96].

Conclusions

Recent reports provide evidence that allergen-specific Th2 (and Th17) responses are under the double-negative control of Th1-polarizing (IFNs, IL-12) and immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), both of which are produced in response to chronic and repeated stimulation of the immune system. It seems very likely that successful SCIT or SLIT performed with high doses of allergens can be the result of up-regulation of both mechanisms.

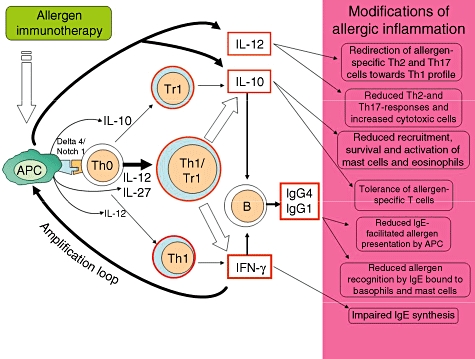

Even though we cannot exclude the fact that Th1 and Tr1 cells are elicited separately by different timing by immunotherapy, regulatory Th1 cells producing IL-10 could be the best candidate to explain the complex immunological changes such as the increase of blocking IgG antibodies, the inhibition of T cell response to allergens and the late decrease of IgE antibodies. Many allergens have been shown to trigger TLRs directly or indirectly on DC, creating microenvironmental conditions to elicit Th1-like Tr1 cells (Fig. 1). The prolonged administration of allergen can favour the contemporary expression of the Notch1-ligand Delta 4 on APC and the production of IL-12 and IL-27, which are essential to induce allergen-specific Th1-like Tr1 cells. They are recruited into inflamed tissues where they can prime an amplification loop involving the IFN-γ-driven activation of DC and macrophages. This, in turn, promotes the recruitment and expansion of new Th1-like Tr1 cells and increase of microenvironmentral IL-12, IL-10 and TGF-β. IL-12 skews allergen-specific Th2 and Th17 into Th1 cells and promotes the proliferation of NK and NKT cells. The high levels of IFN-γ produced by these cells strengthen APC activation to further production of IL-10 TGF-β and IL-12. On the other hand, IL-10 suppresses allergen-specific Th2 and Th17 responses, limits Th1, NKT and NK cells and their cytolytic activity, induces IgG4 production by tissue and lymph nodal B cells and inhibits mast cells, basophils and eosinophil recruitment and activation. Similarly, TGF-β decreases mast cells and eosinophil activation, blocks Th2 (and the excess of Th1) response and contributes to IgA switch. IFN-γ are also responsible for the direct inhibition of IgE-producing cells and the IgG1 switch. Allergen-specific IgG1, IgG4 and IgA can act as ‘blocking antibodies’ by inhibiting IgE-mediated mast cell and basophil release of mediators and IgE-facilitated allergen presentation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of allergen immunotherapy. Allergen immunotherapy induces an altered T cell response which can vary during the course of treatment. IT initially up-regulates few amounts of regulatory and proinflammatory cytokines by antigen-presenting cells (APC) promoting the amplification of both regulatory T cells (Treg) and T helper type 1 (Th1) cells. The prolonged administration of high doses of allergen, however, induces the local conditions [expression of triggering molecules on APC and the production of high levels of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-27] favouring the expansion of allergen-specific Th1-like Tr1 cells. These latter cells are recruited into the inflamed tissues and can prime an amplification loop involving the interferon (IFN)-γ-driven activation of APC. This in turn promotes the recruitment and expansion of new Th1-like Tr1 cells, and the increase in microenvironmentral interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-12. IL-12 drives the switch of allergen-specific Th2 and Th17 cells into Th1 and the expansion of natural killer (NK) and NKT cells, all improving the microenvironmental levels of IFN-γ which strengthen APC activation. The consequent excess of IL-10, transforming growth factor-β, IFN-γ and IL-12 can explain most of the immunological alterations shown during allergen immunotherapy.

This unifying view offers insights into new strategies to ameliorate SCIT by the use of molecules as synthetic TLR ligands able to stimulate both endogeneous IL-12, IL-27 and IL-10. Some ligands of TLR7, such as imidazoquinolines or modified adenines, are able to redirect in vitro Th2 response but, when used in vivo in murine models, also display regulatory activity via the production of IL-10 [97]. Accordingly, when linked to allergens synthetic ligands of TLR-4 have been shown to induce both IL-12 and IL-10 in mouse systems [98], while in clinical trials TLR-9 ligands bound to ragweed pollen up-regulated T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-10 [99]. How and when immunotherapy forces mDC to modify microenviromental conditions leading to the upgrowth of allergen-specific Th1-like Tr1 cells is, at present, an intriguing point dependent upon different conditions, such as type of allergens, routes of administration, contemporaneous T cell responses to other antigens, etc. Finally, and more importantly, it remains to be established whether and how these cells can influence the efficacy of treatment.

Disclosure

The Author has no conflicts of interest or any relevant financial interest in any company or institutions that might benefit from this publication.

References

- 1.Creticos PS. Immunotherapy with allergens. JAMA. 1992;268:2834–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malling H-J, Weeke B. EAACI position paper: immunotherapy. Allergy. 1993;48:9–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1993.tb04754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bousquet J, Lockey R, Malling HJ, et al. Allergen immunotherapy: therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. World Health Organization. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81:401–5. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)63136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durham SR, Walker SM, Varga EM, et al. Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:468–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eng PA, Borer-Reinhold M, Heijnen IA, Gnehm HP. Twelve-year follow-up after discontinuation of preseasonal grass pollen immunotherapy in childhood. Allergy. 2006;61:198–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durham SR, Varney VA, Gaga M, et al. Grass pollen immunotherapy decreases the number of mast cells in the skin. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:1490–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varney VA, Hamid QA, Gaga M, et al. Influence of grass pollen immunotherapy on cellular infiltration and cytokine mRNA expression during allergen-induced late-phase cutaneous responses. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:644–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI116633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nish WA, Charlesworth EN, Davis TL, et al. The effect of immunotherapy on the cutaneous late phase response to antigen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;93:484–93. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(94)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benjaponpitak S, Oro A, Maguire P, Marinkovich V, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. The kinetics of change in cytokine production by CD4 T cells during conventional allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:468–75. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Till SJ, Francis JN, Nouri-Aria K, Durham SR. Mechanisms of immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1025–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson DR, Lima MT, Durham SR. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2005;60:4–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radulovic C, Calderon M, Wilson S, Durham SR. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis: an updated Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2007;62(s83):167–71. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calamita Z, Saconato H, Pela AB, Atallah AN. Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in asthma: systematic review of randomized clinical trials using the Cochrane Collaboration Method. Allergy. 2006;61:1162–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penagos M, Passalacqua G, Campalati E, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in the treatment of allergic asthma in pediatric patients, 3–18 years of age. Chest. 2008;133:599–609. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broide DH. Immunomodulation of allergic disease. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:279–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.041807.123524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. Noninjection routes for immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:437–48. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S240–5. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nieto A, Mazon A, Pamies R, Bruno L, Navarro M, Montanes A. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic respiratory diseases: an evaluation of meta-analyses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:157–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Röder E, Berger MY, de Groot H, van Wijk RG. Immunotherapy in children and adolescents with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: a systematic review. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:197–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Compalati E, Passalacqua G, Bonini M, Canonica GW. The efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy for house dust mites respiratory allergy: results of a GA(2)LEN meta-analysis. Allergy. 2009;64:1570–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romagnani S. The role of lymphocytes in allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:399–408. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.104575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larché M, Robinson DS, Kay AB. The role of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:450–64. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vercelli D. Discovering susceptibility genes for asthma and allergy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:169–82. doi: 10.1038/nri2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Dendritic cells and epithelial cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity in asthma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nri2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee CG, Link H, Baluk P, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces remodeling and enhances TH2-mediated sensitization and inflammation in the lung. Nat Med. 2004;10:1095–103. doi: 10.1038/nm1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trompette A, Divanovic S, Visintin A, et al. Allergenicity resulting from functional mimicry of a Toll-like receptor complex protein. Nature. 2009;457:585–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murugaiyan G, Mittal A, Weiner HL. Increased osteopontin expression in dendritic cells amplifies IL-17 production by CD4+ T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2008;181:7480–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Santarlasci V, et al. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1849–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cosmi L, De Palma R, Santarlasci V, et al. Human interleukin 17-producing cells originate from a CD161+CD4+ T cell precursor. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1903–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahman MS, Yamasaki A, Yang J, Shan L, Halayko AJ, Gounni AS. IL-17A induces eotaxin-1/CC chemokine ligand 11 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of MAPK (Erk1/2, JNK, and p38) pathways. J Immunol. 2006;177:4046–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oboki K, Ohno T, Saito H, Nakae S. Th17 and allergy. Allergol Int. 2008;57:121–34. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.R-07-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cosmi L, Maggi L, Santarlasci V, et al. Demonstration of a small subset of human circulating memory CD161+ CD4+ T cells that produce both IL-17A and IL-4. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Louten J, Boniface K, Malefyt R. Development and function of TH17 cells in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1004–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rolland J, O'Hehir R. Immunotherapy of allergy: anergy, deletion, and immune deviation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:640–5. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner LM, O'Hehir RE, Rolland JM. High dose allergen stimulation of T cells from house dust mite-allergic subjects induces expansion of IFNgamma+ T cells, apoptosis of CD4+IL-4+ T cells and T cell anergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;133:1–13. doi: 10.1159/000075248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antúnez C, Mayorga C, Corzo JL, Jurado A, Torres MJ. Two year follow-up of immunological response in mite-allergic children treated with sublingual immunotherapy. Comparison with subcutaneous administration. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:210–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akdis CA, Blesken T, Akdis M, Wuthrich B, Blaser K. Role of interleukin 10 in specific immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:98–106. doi: 10.1172/JCI2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guerra F, Carracedo J, Solana-Lara R, Sanchez-Guijo P, Ramirez R. TH2 lymphocytes from atopic patients treated with immunotherapy undergo rapid apoptosis after culture with specific allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:647–53. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rolland J, Gardner LM, O'Heir RE. Allergen-related approaches to immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:273–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jutel M, Pichler WJ, Skrbic D, Urwyler A, Dahinden C, Muller UR. Bee venom immunotherapy results in decrease of IL-4 and IL-5 and increase of IFN-gamma secretion in specific allergen stimulated T cell cultures. J Immunol. 1995;154:4187–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Till S, Walker S, Dickason R, et al. IL-5 production by allergen stimulated T cells following grass pollen immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;110:114–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4941392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciprandi G, Sormani MP, Filaci G, Fenoglio D. Carry-over effect on IFN-gamma production induced by allergen-specific immunotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1622–5. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kozutsumi D, Tsunematsu M, Yamaji T, Murakami R, Yokoyama M, Kino K. Cry-consensus peptide, a novel peptide for immunotherapy of Japanese cedar pollinosis, induces Th1-predominant response in Cry j 1-sensitized B10.S mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:2506–9. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sel S, Wegmann M, Sel S, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of viral TLR ligands on experimental asthma depend on the additive effects of IL-12 and IL-10. J Immunol. 2007;178:7805–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durham SR, Ying S, Varney VA, et al. Grass pollen immunotherapy inhibits allergen-induced infiltration of CD41 T lymphocytes and eosinophils in the nasal mucosa and increases the number of cells expressing messenger RNA for interferon gamma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:1356–65. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson DR, Nouri-Aria KT, Walker SM, et al. Grass pollen immunotherapy: symptomatic improvement correlates with reductions in eosinophils and IL-5 mRNA expression in the nasal mucosa during the pollen season. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:971–6. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wachholz PA, Nouri-Aria KT, Wilson DR, et al. Grass pollen immunotherapy for hayfever is associated with increases in local nasal but not peripheral Th1: Th2 cytokine ratios. Immunology. 2002;105:56–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nouri-Aria KT, Pilette C, Jacobson MR, Watanabe H, Durham SR. IL-9 and c-Kit1mast cells in allergic rhinitis during seasonal allergen exposure: effect of immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Plewako H, Wosinska K, Arvidsson M, et al. Basophil interleukin 4 and interleukin 13 production is suppressed during the early phase of rush immunotherapy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:346–53. doi: 10.1159/000095461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamid QA, Schotman E, Jacobson MR, Walker SM, Durham SR. Increases in IL-12 messenger RNA1 cells accompany inhibition of allergen-induced late skin responses after successful grass pollen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:254–60. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Plewako H, Wosinska K, Arvidsson M, Bjorkander J, Hakansson L, Rak S. Production of interleukin-12 by monocytes and interferon-gamma by natural killer cells in allergic patients during rush immunotherapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:464–8. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60936-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexander C, Tarzi M, Larché M, Kay AB. The effect of Fel d 1-derived T-cell peptides on upper and lower airway outcome measurements in cat-allergic subjects. Allergy. 2005;60:1269–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lloyd CM, Hawrylowicz CM. Regulatory T cells in asthma. Immunity. 2009;31:438–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larchè M. Immunoregulation by targeting T cells in the treatment of allergy and asthma. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:745–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grindebacke H, Wing K, Andersson AC, Suri-Payer E, Rak S, Rudin A. Defective suppression of Th2 cytokines by CD4CD25 regulatory T cells in birch allergics during birch pollen season. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1364–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meiler F, Zumkehr J, Klunker S, Rückert B, Akdis CA, Akdis M. In vivo switch to IL-10-secreting T regulatory cells in high dose allergen exposure. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2887–98. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maggi L, Santarlasci V, Liotta F, et al. Demonstration of circulating allergen-specific CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ T-regulatory cells in both nonatopic and atopic individuals. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:429–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akdis CA. T cells in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1022–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pfefferle PI, Sel S, Ege MJ, et al. PASTURE Study Group. Cord blood allergen-specific IgE is associated with reduced IFN-γ production by cord blood cells: the Protection against Allergy – Study in Rural Environments (PASTURE) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:711–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Overtvelt L, Wambre E, Maillere B, et al. Assessment of Bet v 1-specific CD4-T cell responses in allergic and nonallergic individuals using MHC class II peptide tetramers. J Immunol. 2008;180:4514–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Romagnani S. Coming back to a missing immune deviation as the main explanatory mechanism for the hygiene hypothesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1511–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Francis JN, Till SJ, Durham SR. Induction of IL-10+CD4+CD25+ T cells by grass pollen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1255–61. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Del Prete G, De Carli M, Almerigogna F, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Romagnani S. Human IL-10 is produced by both type 1 helper (Th1) and type 2 helper (Th2) T cell clones and inhibits their antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 1993;150:353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McKinstry KK, Strutt TM, Buck A, et al. IL-10 deficiency unleashes an influenza-specific Th17 response and enhances survival against high-dose challenge. J Immunol. 2009;182:7353–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nasser SM, Ying S, Meng Q, Kay AB, Ewan PW. Interleukin-10 levels increase in cutaneous biopsies of patients undergoing wasp venom immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3704–13. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200112)31:12<3704::aid-immu3704>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Radulovic S, Jacobson MR, Durham SR, Nouri-Aria KT. Grass pollen immunotherapy induces Foxp3-expressing CD4+CD25+ cells in the nasal mucosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;121:1467–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ying S, Humbert M, Meng Q, et al. Local expression of epsilon germline gene transcripts and RNA for the epsilon heavy chain of IgE in the bronchial mucosa in atopic and nonatopic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:686–92. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.James LK, Durham SR. Update on mechanisms of allergen injection immunotherapy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008:1074–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moingeon P, Batard T, Fadel R, Frati F, Sieber J, Van Overtvelt L. Immune mechanisms of allergen-specific sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2006;61:151–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allam JP, Stojanovski G, Friedrichs N, et al. Distribution of Langerhans cells and mast cells within the human oral mucosa: new application sites of allergens in sublingual immunotherapy? Allergy. 2008;63:720–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dehlink E, Eiwegger T, Gerstmayr M, et al. Absence of systemic immunologic changes during dose build-up phase and early maintenance period in effective specific sublingual immunotherapy in children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:32–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Savolainen J, Jacobsen L, Valovirta E. Sublingual immunotherapy in children modulates allergen-induced in vitro expression of cytokine mRNA in PBMC. Allergy. 2006;61:1184–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bohle B, Kinaciyan T, Gerstmayr M, Radakovics A, Jahn-Schmid B, Ebner C. Sublingual immunotherapy induces IL-10-producing T regulatory cells, allergen-specific T-cell tolerance, and immune deviation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:707–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O'Hehir RE, Gardner LM, de Leon MP, et al. House dust mite sublingual immunotherapy: the role for transforming growth factor-beta and functional regulatory T cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:936–47. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0686OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nieminen K, Valovirta E, Savolainen J. Clinical outcome and IL-17, IL-23, IL-27 and FOXP3 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of pollen-allergic children during sublingual immunotherapy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:174–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Incorvaia C, Frati F, Puccinelli P, et al. Effects of sublingual immunotherapy on allergic inflammation. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2008;7:167–72. doi: 10.2174/187152808785748191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gardner LM, Spyroglou L, O'Hehir RE, Rolland JM. Increased allergen concentration enhances IFN-gamma production by allergic donor T cells expressing a peripheral tissue trafficking phenotype. Allergy. 2004;59:1308–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.MacDonald AJ, Duffy M, Brady MT, et al. CD4 T helper type 1 and regulatory T cells induced against the same epitopes on the core protein in hepatitis C virus-infected persons. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:720–7. doi: 10.1086/339340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reefer AJ, Carneiro RM, Custis NJ, et al. A role for IL-10-mediated HLA-DR7-restricted T cell-dependent events in development of the modified Th2 response to cat allergen. J Immunol. 2004;172:2763–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parronchi P, Sampognaro S, Annunziato F, et al. Influence of both TCR repertoire and severity of the atopic status on the cytokine secretion profile of Parietaria officinalis-specific T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:37–46. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<37::AID-IMMU37>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Qian C, An H, Yu Y, Liu S, Cao X. TLR agonists induce regulatory dendritic cells to recruit Th1 cells via preferential IP-10 secretion and inhibit Th1 proliferation. Blood. 2007;109:3308–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-040337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bozza S, Zelante T, Moretti S, et al. Lack of Toll IL-1R8 exacerbates Th17 cell responses in fungal infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:4022–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mamessier E, Birnbaum J, Dupuy P, et al. Ultra-rush venom immunotherapy induces differential T cell activation and regulatory patterns according to the severity of allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:704–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jones SM, Pons L, Roberts JL, et al. Clinical efficacy and immune regulation with peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cosmi L, Santarlasci V, Angeli R, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy with Dermatophagoides monomeric allergoid down-regulates allergen-specific immunoglobulin E and increases both interferon-gamma- and interleukin 10-production. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:261–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stock P, Akbari O, Berry G, Freeman GJ, Dekruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Induction of T helper type 1-like regulatory cells that express Foxp3 and protect against airway hyper-reactivity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1149–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Trinchieri G. Regulatory role of T cells producing both interferon gamma and interleukin 10 in persistent infection. J Exp Med. 2001;194:F53–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.f53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Verhoef A, Alexander C, Kay AB, Larchè M. T cell epitope immunotherapy induces a CD4+ T cell population with regulatory activity. PLoS Med. 2005;2:253–61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jankovic D, Kullberg MC, Feng CG, et al. Conventional T-bet(+)Foxp3(−) Th1 cells are the major source of host-protective regulatory IL-10 during intracellular protozoan infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204:273–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Anderson CF, Oukka M, Kuchroo VJ, Sacks D. CD4(+)CD25(−)Foxp3(−) Th1 cells are the source of IL-10-mediated immune suppression in chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:285–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-10 production by effector T cells: Th1 cells show self control. J Exp Med. 2007;204:239–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Häringer B, Lozza L, Steckel B, Geginat J. Identification and characterization of IL-10/IFN-gamma-producing effector-like T cells with regulatory function in human blood. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1009–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gabrysová L, Nicolson KS, Streeter HB, et al. Negative feedback control of the autoimmune response through antigen-induced differentiation of IL-10-secreting Th1 cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1755–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rutz S, Janke M, Kassner N, Hohnstein T, Krueger M, Scheffold A. Notch regulates IL-10 production by T helper 1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3497–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712102105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stumhofer JS, Silver JS, Laurence A, et al. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1363–71. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vultaggio A, Nencini F, Fitch PM, et al. Modified adenine (9-benzyl-2-butoxy-8-hydroxyadenine) redirects Th2-mediated murine lung inflammation by triggering TLR7. J Immunol. 2009;182:880–99. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lombardi V, Van Overtvelt L, Horiot S, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 agonist Pam3CSK4 enhances the induction of antigen-specific tolerance via the sublingual route. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1819–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Creticos PS, Schroeder JT, Hamilton RG, et al. Immunotherapy with a ragweed-Toll like receptor 9 agonist vaccine for allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1445–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]