Abstract

Despite the quickening momentum of genomic discovery, the communication, behavioral, and social sciences research needed for translating this discovery into public health applications has lagged behind. The National Human Genome Research Institute held a 2-day workshop in October 2008 convening an interdisciplinary group of scientists to recommend forward-looking priorities for translational research. This research agenda would be designed to redress the top three risk factors (tobacco use, poor diet, and physical inactivity) that contribute to the four major chronic diseases (heart disease, type 2 diabetes, lung disease, and many cancers) and account for half of all deaths worldwide. Three priority research areas were identified: (1) improving the public’s genetic literacy in order to enhance consumer skills; (2) gauging whether genomic information improves risk communication and adoption of healthier behaviors more than current approaches; and (3) exploring whether genomic discovery in concert with emerging technologies can elucidate new behavioral intervention targets. Important crosscutting themes also were identified, including the need to: (1) anticipate directions of genomic discovery; (2) take an agnostic scientific perspective in framing research questions asking whether genomic discovery adds value to other health promotion efforts; and (3) consider multiple levels of influence and systems that contribute to important public health problems. The priorities and themes offer a framework for a variety of stakeholders, including those who develop priorities for research funding, interdisciplinary teams engaged in genomics research, and policymakers grappling with how to use the products born of genomics research to address public health challenges.

Introduction

The promise that genomic discovery offers for positive clinical and public health out comes is being heralded in high-profile public arenas.1,2 This acclaim is due in part to the advances in technology that allow genomic scientists to do more—faster and better at less expense3,4—and to the findings from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that are identifying an expanding list of gene variants associated with numerous common diseases. As these results appear with increasing frequency in prominent scientific journals,5,6 expectations are growing that personalized genomics will enable the creation and delivery of individualized prevention and treatment interventions and widespread public health benefits.7,8 In contrast to the heightened focus on genomic discovery, however, far less attention has been given to defining the communication, behavioral, and social sciences research required to translate genomic information into public health applications.9 Thus, a sizable gap exists between the scientific investment made in genomic discovery and the translational research needed to satisfy the understandably high public expectations for the health benefits such a discovery might deliver.

Defining the Translational Research Gap

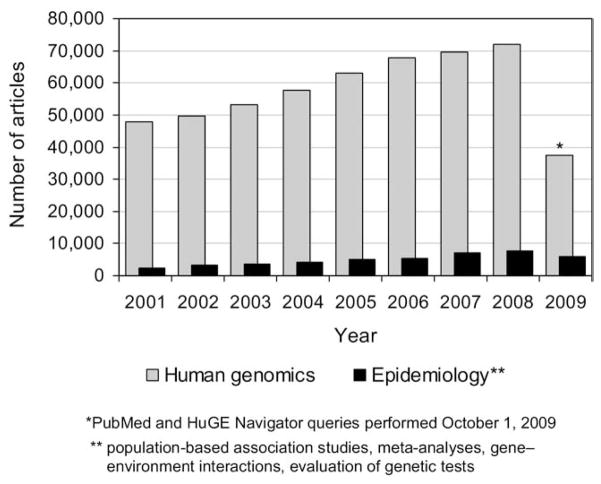

For the past decade, the CDC’s Office of Public Health Genomics has tracked the number of scientific publications that address the translational research gap.10,11 “Translational research,” as defined for this report, “seeks to transfer basic science discoveries (bench) into clinical applications (bedside), prevention, and public health interventions (trench)” and, in turn, to transfer knowledge “about effective interventions of all types into successful policy and program initiatives across multiple levels of the healthcare system and society.”12 As Figure 1 illustrates, the number of publications reporting results of human genomic discoveries (e.g., gene–gene and gene–disease associations) far exceeds the number that describe research aimed to transfer these discoveries into clinical applications (e.g., evaluation of genetic tests).11

Figure 1.

Publications related to human genetics and genomics, PubMed and HuGE Navigator, 2001–2009

A principal reason for the relative dearth of translational research is that scientific stakeholders disagree about whether genomic discovery is ready for such research. Some genetic scientists believe there is too little understanding of the complexity of the underlying biology of gene–gene and gene–environment interactions to support translational research.13 Scientists in epidemiology and public health contend that the small and as yet imprecise effects revealed by research on gene–gene and gene–disease associations will contribute very little to existing metrics for disease risk prediction and clinical decision making.14,15 Some also argue that, given limited resources, emphasis should be placed on applying effective interventions that address environmental exposures rather than pursuing genomics-informed solutions.16 Social and behavioral researchers, too, have been skeptical of translational research based on concerns that the research will shift the focus of health promotion away from known and powerful environmental, social, and behavioral influences.17 Similarly, caution has been recommended by some medical professionals18,19 who find insufficient evidence that genomics-based personalized medicine will promote positive health outcomes.20,21

Addressing the Gap with an Interdisciplinary Approach

To address some of the issues that underlie the translational research gap, the National Human Genome Research Institute convened a 2-day workshop in October 2008 that brought together a group of 50 scientists from the U.S. and the United Kingdom, representing a broad range of disciplines including public health; communication, behavioral, and social sciences; genetics; epidemiology; medicine; and public policy. The group was asked to recommend research priorities to evaluate potential public health applications of genomic discoveries with a focus on communication, behavioral, and social sciences research.

Asked to assume the role of “trailblazers” rather than “translators” in their approach to framing critical research priorities,22 group members were encouraged to anticipate advances in genomics and to assume that their recommendations would be carried out by interdisciplinary research teams of the future (nihroadmap.nih.gov). Discussions over the 2 days culminated in the identification of three priority areas that need translational research focused in communication, behavioral, and social sciences, and three crosscutting themes to consider in carrying out such research (Table 1). These priorities and themes are intended to provide a framework for a variety of stakeholders, including those engaged in setting priorities for research funding, interdisciplinary teams engaged in the translation of genomics research, and, ultimately, policymakers grappling with how the products born of genomics technology might address public health challenges.

Table 1.

Areas of emphasis for genomic translational research

| Priority research areas |

| Public understanding and use of genomic information |

| Potential for genomics to improve risk communication and health behavior change |

| Using genomics and other emerging technologies to identify new behavioral intervention targets and more sensitive intervention outcomes |

| Crosscutting themes |

| The need to anticipate directions of genomic discovery |

| The importance of framing research questions based on the assumption that genomics innovation may or may not add value to either individual or population-level health outcomes |

| The importance of systems thinking and ecologic or multilevel modeling, and transdisciplinary collaborations |

Group members reviewed the current landscape of genomic research and the status of its translation into clinical and public health practice. Acknowledging the importance of rigorous studies of the clinical utility of genetic information, the group nevertheless cautioned that there were limits—and even risks—to enforcing a linear path from discovery to translation (“bench to bedside to trench” model) in which basic science discoveries are refined in highly controlled circumstances and perfected before being applied in clinical, community, or other public health settings. In this model, basic research in genetics has traditionally been the domain of bench science, whereas translational research has been the realm of communication, behavioral, and social sciences.

The concern about this divided mission is that basic research approaches will be unable to anticipate critical challenges and opportunities that come with translation of genomics information into public health practice.23–25 The group recommended that cross-disciplinary and multilevel collaborations be fostered among genomic discovery and dissemination researchers. A lack of collaborative, interdisciplinary, translational research explains the often premature, inefficient, and sometimes even harmful adoption of new technologies. Negative outcomes can occur when the powerful “push” forces of scientific discovery are matched with market “pull” forces without the mediating presence of a translational evidence base.26 For example, in the case of direct-to-consumer personalized genomic profiles,27 a better understanding of how people comprehend the limits of these profiles might have informed the marketing of these products, and perhaps even enabled policymakers to engage sooner in a public debate about their risks and benefits. Instead, translational researchers are now playing catch-up to gather evidence about whether these tests will offer individual- or population-level health benefits or instead lead to negative consequences as has been observed with other aggressively marketed, yet not fully evaluated, technologies such as whole-body imaging.

Setting a Proactive Agenda

Attendees agreed that the answer to whether personalized genomics adds value to existing public health promotion efforts is largely unknown, and that if broad public health benefits are to be derived from genomic discovery, then translational research must be elevated to a more prominent place. Further, in order to reduce the possibility of misapplying new knowledge, the group endorsed an “inverse planning” model.24 This model is characterized by an early and ongoing bidirectional exchange of knowledge between discovery and translational research. In this exchange, the acceptability, efficacy, effectiveness, cost effectiveness, and predicted public health impact of basic science findings are evaluated early and iteratively throughout the discovery process. For example, translational research could be conducted using early prototypes such as a representative set of genetic susceptibility tests that embody important characteristics of future tests—not necessarily the full set of markers envisioned for future use. These prototypes could be evaluated in comparison to other medical and public health interventions and used to assess their uptake, personal decision making, and patterns of patient–provider communication, all important to inform downstream clinical and public health policies.

The group agreed that priority should be given to research that targets the top three risk factors: tobacco use, poor diet, and physical inactivity, which contribute most to the four major chronic diseases (heart disease, type 2 diabetes, lung disease, and many cancers) that together account for half of all deaths worldwide (www.3four50.com). In the discussions, poor dietary behaviors and physical inactivity were used as examples of how genomic discovery might add value to current public health efforts to reduce obesity.28 Although there is evidence of the importance of several psychological and environmental factors in the development and maintenance of a healthy diet and appropriate levels of physical activity,29–31 interventions on the whole have yet to produce the long-term improvements at the individual or population level needed to prevent or treat obesity.32 It is an open question as to whether—and for whom—these interventions can be improved by applying the knowledge gained in translational genomics research based on the heritability of these unhealthy behaviors or of obesity itself,33,34 in order to suggest appropriate behavioral innovations to help treat them.

As the group discussed, such research also might lend insight into where best to target limited health promotion resources or to focus policy development. For example, Khoury and colleagues35 have suggested that family history and genetic risk assessments could be used to stratify populations into differing levels of obesity risk. Could these tools aid efforts to address macro-environmental contributors, such as the concentration of fast-food outlets in low-income areas, the relatively higher price of quality foods such as fruits and vegetables, and national marketing campaigns of high-calorie foods? Perhaps awareness of genetic risk could galvanize genetic identity groups (those at risk) in ways that prompt community engagement and empowerment to influence social environmental exposures with an impact beyond those of current community organizing strategies.

To help close the translational research gap, the group outlined several priority areas and crosscutting themes. Table 2 frames examples of the research questions found at the nexus of these priorities and themes.

Table 2.

Examples of translational research questions at the nexus of research priorities and crosscutting themesa

| Assertions about genomics | Research priority | Crosscutting themes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipate directions of discovery | Value added to existing approaches | Multilevel approaches | ||

| Public lacks literacy skills to evaluate the limits and usefulness of new multigene tests | 1. Public understanding and use of genomic information | How might information provided by multigene risk assessments and whole-genome scans be organized and presented to maximize understanding given the limits of information for populations with varied literacy? | How might Internet-based decision support related to new genetic tests be used to educate the public about the contributions of genetics and environment to common health conditions? | How do communicator characteristics (e.g., channel, communicator) influence the likelihood of accurate understanding of the limits of genetic influences on health outcomes? |

| Public will overestimate the role of genetics in health outcomes in ways that diminish perceived importance of health behavior and environment | How might a lifespan approach be used to update risk assessment in step with aging and associated changes in risk behaviors (e.g., onset of overweight) and environmental exposures (e.g., relocation)? | Can education about gene-by- environment interactions be used to increase the salience of current and future behavioral and environmental risk factors for individuals? | Can a lay health educator model be integrated into Internet communities and other social networks to increase accurate understanding of new genetic discoveries? | |

| Genomic risk information will enable personalized prevention in ways that improve primary prevention interventions | 2. Improve risk communication and health behavior change interventions | How do explanations of personal, genetically based behavioral phenotypes (e.g., low metabolic response to physical activity) influence individuals’ behavior change confidence and motivation? | Can interventions that capitalize on shared patterns of genetic risk within families be more effective in promoting behavior change than existing individual-based interventions? | Can genetic information activate social influence pathways for sustainable behavior modification and how does this vary in different cultural contexts? |

| Target groups will interpret genetic risk messages in biased ways that undermine likelihood of behavior change (e.g., fatalism, optimistic biases) | Will personal genetic testing that indicates genetic factors that make it difficult to change specific health habits negatively influence motivation and success at behavior change? | Does presenting multiple risk and protective genetic influences on physiologic responses outperform single disease risk communications in motivating individuals to take steps toward behavior change? | Can genetic risk profiles (e.g., based on prevalence of genetic variants in worksites, schools, housing developments) deactivate individual-level biased responses to risk information? | |

| Understanding genetic underpinnings of disease will enable better understanding of gene-by- environment interactions | 3. Identifying new behavioral intervention targets and more sensitive intervention outcomes | How can ubiquitous technologies (e.g., ecologic momentary assessment, geo-mapping) be used to validate new genetic findings (e.g., eating in the absence of hunger) and reliably measure eating patterns associated with short- and long- term weight outcomes? | Are newly minted and more- specific behavioral phenotypes (e.g., eating in the absence of hunger) more sensitive to influences of individual, interpersonal, or social interventions to promote health than current gold-standard behavioral outcomes? | Do behavioral and genomic risk factors cluster within neighborhoods and communities, enabling targeted intervention at the household, neighborhood, and community levels? |

| Social divides in access and trust related to genetic information will accentuate current health disparities | How might information about gene– disease associations based on variants that are over- represented in specific racial or ethnic populations be used to redress health disparities? | Do social network methods that are used to identify optimal “disseminators” of genetic risk information build trust and engagement in health promotion programs above those of current individual-targeted approaches? | Can information about ancestry and its association with health outcomes be used to attract hard-to-reach target groups to become involved in health promotion programs? | |

See text for elaborations on research priorities and crosscutting themes.

Priority Areas in Communication, Behavioral, and Social Sciences Research

Public Understanding and Use of Genomic Information

Genetic information is complicated, and explanations of causative factors in disease development are becoming increasingly complex. For example, what is the best way to convey to the public concepts such as pleiotropy, in which a single gene variant can have multiple disease manifestations or even be protective for one disease and increase risk for another? Will explanations about gene–environment processes, in which environments turn on or off gene expression in some individuals, be accepted equally by different constituencies, and how might this new knowledge influence life choices and behaviors? Research also is showing differences in public interpretation of concepts such as gene–environment interaction. Some interpret this concept as meaning that behavior is the major contributor to health outcomes; others see the two as working together in an additive relationship (i.e., genes plus behavior).36 These interpretations will likely be sensitive to differences in how the information is conveyed.37 However, it is unclear how this understanding will influence uptake and use of, for example, genetic testing. Well-documented tendencies of individuals and groups toward positively or negatively biased interpretations of risk communication also will likely influence understanding and application of genomic discoveries.38 – 40

Advances such as full-genome sequencing products from which individuals can obtain a complete description of their genome4 are anticipated in the public arena. These products will provide ever-larger amounts of personal genomic information with unknown implications for health outcomes. To date, little consideration has been given to whether and how such information might be used by individuals, healthcare providers, program planners, or policymakers. Thus, research on the applications of genomic discovery should give priority to understanding these groups’ expectations, perceived benefits and harms, and capabilities of full-genome sequencing and other future genome products. For example, communication research such as surveillance of web-based discourse; population attitudes; developments in professional training; credentialing developments; and mass media promotions could be used to monitor trends, recognize milestones in public awareness, and assess uptake of and response to new genomic information.

Direct-to-consumer marketing of genetic tests also offers a context for several research questions. What systems and tools (e.g., web-based, print-based, numeric or descriptive risk communication) are needed to help targeted populations interpret and use genetic information that is based on multiple gene variants for multiple health conditions? Further, what might be the intended and unintended uses of these tests for social groups based on age, ethnicity, geographic locale, and literacy level?

Communication theory suggests that the medium of delivery (newspaper, TV, Internet, healthcare providers) and characteristics of both the communicator and the recipient will influence individual, community, and social responses. The Internet, now a well-accepted source for highly customized health-related information and social networking, will likely predominate as a communication channel for genomic information. However, the difficulties of evaluating the quality and accuracy of information on the Internet are well known, and this is compounded for esoteric subjects such as genetics that are laden with unfamiliar jargon and complicated concepts. What will individuals and society need in order to develop the genetic literacy sufficient for ensuring balanced consideration of current and anticipated genomic discovery?38 Social context, often characterized by close family and friends, as well as interpersonal communication, also influences interpretations of mass communication.41 Because family members share genetic profiles and environmental exposures, social context becomes particularly relevant for understanding the effects of genomic communication.

Empirical evidence may contradict popular assumptions about how different constituencies will receive and use technologies. For example, most early speculations assumed that public uptake of information about genetics would lead to simple and overly deterministic associations between genes and health.42,43 Research on lay understanding of health has shown that most Western populations realize that health is a product of variable inputs of both personal behavior and familial inheritance.36,44–51 Evidence supports the public’s nuanced understanding of the role of genetics in health that varies based on the character of the disease,46,49 the family’s experience with the disease,52,53 the character of the treatments available, the pathways by which the genes act,54 and the communication approach used to present genetic risk and behavioral options.37 Research to identify these human factors more precisely is essential if genomic discoveries and their applications are to be most useful and least harmful. Appreciating the import of these human factors need not wait on understanding the specificity of the biological information conveyed in genetic tests.

Potential for Genomics to Improve Risk Communication and Health Behavior Interventions

Some predict that the potential to personalize disease prevention and treatment afforded by genomics will be more powerful than other biomarker feedback, such as blood pressure or lipid levels.7 Moreover, personalization is being advocated as a potent motivational tool for promoting behavior change to modify lifestyles and for adopting new medical therapies. However, these predictions are based on studies of families carrying single gene mutations strongly associated with disease risk, or on self-selected populations, potentially limiting their external validity.55 Screening behaviors have been the primary outcomes explored with these high-risk families, with appropriate shifts in screening following feedback regarding mutation status.56 But the influence of genomic information on health behaviors that require sustained changes, such as those related to tobacco use, diet, and exercise, have not been studied, except when the healthier behaviors occurred serendipitously.57 It is reasonable to hypothesize that genomic information alone may not improve these behaviors given the remarkable consistency found in psychological responses to genetic tests—increased negative emotions immediately following testing that taper off in a 12-month time frame.56–65

Studies exploring genetic testing for common disease susceptibility, associated with only slight to moderate increases in risk, have relied almost exclusively on hypothetic scenarios in which individuals are asked to imagine testing and, in turn, predict the impact it might have on their health behaviors.66–72 Future research needs to evaluate the effect of providing actual test results to individuals or groups in different testing scenarios such as clinical or direct-to-consumer settings.73 Behavioral research suggests that individual risk communications as a singular intervention strategy will be slow to yield the sustained improvements in health habits (for example, physical activity) that are necessary to reduce disease risk.74 Thus, with epidemics such as obesity, genomic discoveries likely will become one part of an overall systems approach to achieve individual- and population-level improvements in health outcomes.

Social and psychological theory can be used to frame these research questions and hypotheses, and accepted gold-standard behavioral outcomes can be used as end points. Consideration should be given to the mechanisms through which genetic communication might influence health behaviors. Genetic-risk feedback might have its greatest influence on intermediate factors such as emotional responses (e.g., fear or worry), motivation to seek formal interventions, self-confidence to adhere to an intervention (self-efficacy), or beliefs that interventions will or will not be effective (response efficacy). Whether and how genetic information might add positively to existing interventions or produce counterproductive responses is still largely unknown.

The opportunity genomics may offer for influencing behavior change beyond the individual is largely unexplored. Genomic risk information represents shared risk that may influence communication flow within social networks75 and stimulate behavior change and improved health outcomes within a network such as a household or family. Interdependence theory suggests that providing genomic information could increase behavior change in the broader kinship network by fostering “communal coping.”76–78 In this model, interventions that increase awareness of genetically based risk for disease within a family, provided in tandem with formal behavior change interventions, might influence family members’ cognitive and emotional interpretations of what this information means for the broader kinship network. These interpretations could motivate cooperative problem-solving efforts wherein members of the kinship network cooperate in making lifestyle changes.78

Health promotion interventions often target social arenas such as worksites, schools, churches, and housing developments. How these interventions might make use of genetic information in promoting health and wellness in these settings has not been explored. The potential for discrimination based on genetic profiles79 suggests the need for group-level interventions that are not based solely on individualized communication of genetic information. Risk communication approaches could be tested that convey depersonalized risk communication, such as proportions of the group holding particular gene variants, with the aim of motivating group improvements in health behaviors to achieve collective benefits (e.g., reduced healthcare premiums). These settings offer a natural context for exploring the associations between interpersonal models and system-level applications of genomic discovery.

Using Genomics and Other Emerging Technologies to Identify New Behavioral Intervention Targets and More-Sensitive Intervention Outcomes

Genomics discoveries are providing new insights into the biology underlying disease development and the acquisition and maintenance of health behaviors.80 – 85 Insight into the genetic underpinnings of behavioral phenotypes, such as eating in the absence of hunger84 or physiologic responses to exertion,85 could expand current conceptualizations of behavioral moderators, mediators, and outcomes in ways that yield more-sensitive and more-specific measures of environmental influences and intervention impact.

Using these discoveries to influence health behaviors might be modeled on pharmacogenomics research to apply genome-wide association study findings related to the cytochrome p450 family of genes and its influence on drug metabolism.86 These discoveries are showing some promise for improving drug-dosing regimens and reducing adverse drug reactions. A question for communication, behavioral, and social sciences translational research is whether it is possible to identify common genetic underpinnings (e.g., dopamine receptor genes) of behaviors associated with disease risk that can help explain one of public health’s most vexing problems: the co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviors such as tobacco use, poor diet, and physical inactivity.

Advances in population genetic research enabled by GWAS are also providing information about the population distributions of genetic variants associated with common diseases. Results to date suggest that the prevalence of some gene variants such as the MYH9 locus of chromosome 22, a variant strongly associated with the occurrence of complications of type 2 diabetes (such as end-stage renal disease), differs across racial and ethnic groups.87 Although such gene–disease associations support the relevance of ancestry in health disparities, there is similarity in genetic makeup across racial and ethnic groups, reinforcing the role of environment in these disparities.88,89 It is therefore important to consider how such knowledge might be used to inform public policy, improve health service delivery, or educate healthcare provider groups in ways that discourage racial and ethnic profiling in health contexts and reduce entrenched health disparities.90

Crosscutting Themes for Translational Research in Communication, Behavioral, and Social Sciences

The Need to Anticipate Directions of Genomic Discovery

Workshop participants felt that a high priority should be placed on anticipating the direction of genomic discovery 5, 10, and 25 years hence, including predictions that genomic products will become less and less expensive, and that this decreased cost will move genomic testing away from a single-nucleotide polymorphism–based marker model to a full-genome sequence model. Also likely are the discovery and application of other biomarkers based on gene expression, as well as proteomic and epigenetic profiles.9 Today, the relative paucity of validated genetic markers and of confirmed association with effective interventions places personalized genomics outside the mainstream of medical care. The increasing ability to expand the scope of genomic testing, steady improvements in knowledge of the association of genomics with disease, and demonstrations of effective interventions may change this. The impact of widespread access to such testing at low cost, although difficult to predict, will almost certainly influence the healthcare delivery model91 and may prove to be a truly disruptive technology.92

The Importance of Scientific Open-Mindedness

Another crosscutting issue identified by the group is the need to frame genomic translational research questions agnostically; and not to simply assume that genomics has value for public health. Rather, there is a need for rigorous and objective evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of the application of genomics technology. This point of view aligns with recommendations that comparative effectiveness research elucidate both the positive and the negative medical and social costs of medical technologies so as to inform the evidence supporting medical care and public policy.93

The Importance of Systems Thinking and Transdisciplinary Collaborations

Genomic knowledge is evolving and is being shaped in the context of broad social, cultural, and political forces. Because genetic variants do not act in isolation, personalized genomics has inherent environmental dimensions. Evaluations of its efficacy will require multilevel study designs that include biological and pharmacologic factors; the social and cultural context of people’s lives; and influences of the built and natural environments.94 Traditional settings for health-related research will not suffice for the complexity of multilevel gene–environment research. Although rhetoric to use more complex models abounds in social science literature, actual implementation of research based on ecologic and systems models is rare. Although other new approaches may be employed (e.g., grid computing), as of yet they are more familiar to researchers in other scientific domains than to communication, behavioral, and social scientists.95

The Exposure Biology Program of the Genes, Environment and Health Initiative (GEI), launched by the NIH in 2006, has as its overarching aim a mission to promote multilevel research to understand how environmental exposures and genetic variation may interact to cause disease. The initiative (www.gei.nih.gov) is an ambitious effort to develop and validate an array of tools such as wearable biosensor dosimeters to measure real-time physiologic responses, light-sensing headsets to monitor circadian rhythms, wireless skin patch sensors for stress, and GPS-based devices that will enable precise assessments of environmental exposures in natural settings. Together with existing measures such as neighborhood-level assessments (e.g., NIfETy96) these technologies promise exciting new directions for translational research in genomics.

Conclusion

There is a need for research in how to optimize the fruits of genomic discovery for individual and population health, and this research should not progress linearly from “bench to bedside to trench” but rather should be interactive and bidirectional. Communication, behavioral, and social scientists should collaborate with genomic researchers and other relevant scientists to help pose practical and unbiased research questions that have relevance for individuals, communities, healthcare providers, and those in the public health and policy arenas. Genomic discovery will continue to etch its influences on public understanding and perception of health and disease. A concurrent, thoughtful, and proactive agenda is needed in genomic translational research if we are to understand and shape the applications of future genomic discovery for maximum public health benefit.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the meeting was provided by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute. The authors gratefully acknowledge the scientists who attended the workshop and participated in the discussions. They include: Christine Bachrach, PhD; Andreas Baxevanis, PhD; Barbara Bernhardt, MS, CGC; Barbara Biesecker, MS; Leslie Biesecker, MD; Vence Bonham, Jr, JD; Joseph Cappella, PhD; Francis Collins, MD, PhD; William G. Feero, MD, PhD; Phyllis Frosst, PhD; Sarah Gehlert, PhD; Eric Green, MD, PhD; Lawrence Green, DrPH; Robert Green, MD, MPH; Alan Guttmacher, MD; Donald Hadley, MS, CGC; Kathy Hudson, PhD; Kimberly Kaphingst, ScD; Deborah Klein-Walker, EdD, Matthew Kreuter, PhD, MPH; Anne Madeo, MS; Brendan Maher; Cynthia Morton, PhD; Robert Nussbaum, MD; Eliseo Perez-Stable, MD; Susan Persky, PhD; Barbara K. Rimer, DrPH; Debra Roter, DrPH; Charles Rotimi, PhD; Kurt Stange, MD, PhD; Vish Vishwaneth, PhD; Nora Volkow, MD. Additional thanks go to Ms. Gillian Hooker, Ms. Sarah Knerr, Ms. Christina Lachance, Dr. Christopher Wade, and Ms. Laura Wagner for their assistance in documenting and facilitating the breakout sessions.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Pinker S. My genome, my self. New York Times magazine. 2009 Jan 11; http://pinker.wjh.harvard.edu/articles/media/My%20Genome%20My%20Self%20final.pdf.

- 2.Hamilton A. The retail DNA test. Time magazine. 2008 Oct 29; http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1852747_1854493,00.html.

- 3.Netterwald J. Winning the race? Drug, discovery and development. 2009 May 2; http://www.dddmag.com/article-next-generation-and-third-generation-sequencing-technologies-030909.aspx.

- 4.Pettersson E, Lundeberg J, Ahmadian A. Generations of sequencing technologies. Genomics. 2009;93(2):105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frazer KA, Murray SS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Human genetic variation and its contribution to complex traits. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(4):241–51. doi: 10.1038/nrg2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manolio TA, Brooks LD, Collins FS. A HapMap harvest of insights into the genetics of common disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(5):1590–605. doi: 10.1172/JCI34772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins FS, Green ED, Guttmacher AE, Guyer MS US National Human Genome Research Institute. A vision for the future of genomics research. Nature. 2003;422(6934):835–47. doi: 10.1038/nature01626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wray NR, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Prediction of individual genetic risk of complex disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18(3):257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozdemir V, Suarez-Kurtz G, Stenne R, et al. Risk assessment and communication tools for genotype associations with multifactorial phenotypes: the concept of “edge effect” and cultivating an ethical bridge between omics innovations and society. OMICS. 2009;13(1):43–61. doi: 10.1089/omi.2009.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Yoon PW, Dowling N, Moore CA, Bradley L. The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: how can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention? Genet Med. 2007;9(10):665–74. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815699d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu W, Gwinn M, Clyne M, Yesupriya A, Khoury MJ. A navigator for human genome epidemiology. Nat Genet. 2008;40(2):124–5. doi: 10.1038/ng0208-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Best A, Hiatt RA, Norman CD. Knowledge integration: conceptualizing communications in cancer control systems. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(3):319–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy J, Singleton A. Genomewide association studies and human disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(17):1759–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioannidis JP, Thomas G, Daly MJ. Validating, augmenting and refining genome-wide association signals. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(5):318–29. doi: 10.1038/nrg2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssens AC. Is the time right for translation research in genomics? Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23(11):707–10. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merikangas KR, Risch N. Genomic priorities and public health. Science. 2003;302(5645):599–601. doi: 10.1126/science.1091468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freese J, Shostak S. Genetics and social inquiry. Annual Review Sociology. 2009;35:107–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christakis NA. Medicine may change our genes. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1101. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39580.445856.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feero WG, Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. The genome gets personal—almost. JAMA. 2008;299(11):1351–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlsten C, Burke W. Potential for genetics to promote public health: genetics research on smoking suggests caution about expectations. JAMA. 2006;296(20):2480–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGuire AL, Burke W. An unwelcome side effect of direct-to-consumer personal genome testing: raiding the medical commons. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2669–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McBride C. Trail-blazing a public health research agenda in genomics and chronic disease. Preven Chron Dis. 2005;2(2):A04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract. 2008;25(1S):i20–4. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarin R. Inverse planning for the T1–2 conundrum in translation research. J Cancer Res Ther. 2009;5(1):1–2. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.48762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerner JF. Integrating research, practice, and policy: what we see depends on where we stand. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):193–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000311899.11197.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollack A. The wide, wild world of genetic testing. NY Times (Print) 2006:NYT4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agurs-Collins T, Khoury MJ, Simon-Morton D, Olster DH, Harris JR, Milner JA. Public health genomics: translating obesity genomics research into population health benefits. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(3S):S85–94. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De la Haye K, Robins G, Mohr P, Wilson C. Obesity-related behaviors in adolescent friendship networks. Social Networks. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2009.09.001. In press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valente TW, Fujimoto K, Chou CP, Spruijt-Metz D. Adolescent affiliations and adiposity: a social network analysis of friendships and obesity. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(2):202–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flynn MA, McNeil DA, Maloff B, et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with ‘best practice’ recommendations. Obes Rev. 2006;7(1S):S7–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breen FM, lomin R, Wardle J. Heritability of food preferences in young children. Physiol Behav. 2006;88(4–5):443–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery H, Safari L. Genetic basis of physical fitness. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2007;36:391–405. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khoury MJ, Davis R, Gwinn M, Lindegren ML, Yoon P. Do we need genomic research for the prevention of common diseases with environmental causes? Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(9):799–805. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Condit CM, Gronnvoll M, Landau J, Shen L, Wright L, Harris TM. Believing in both genetic determinism and behavioral action: a materialist framework and implications. Public Underst Sci. 2009;18(6):730–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaphingst KA, Persky S, McCall C, et al. Testing the effects of educational strategies on comprehension of a genomic concept using virtual reality technology. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris PR, Griffin DW, Murray S. Testing the limits of optimistic bias: event and person moderators in a multilevel framework. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(5):1225–37. doi: 10.1037/a0013315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keeley B, Wright L, Condit CM. Functions of health fatalism: fatalistic talk as face saving, uncertainty management, stress relief and sense making. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(5):734–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senay I, Kaphingst KA. Anchoring-and-adjustment bias in communication of disease risk. Med Decis Making. 2009;29(2):193–201. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08327395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valente TW, Aba W. Mass media and interpersonal influence in a reproductive health communication campaign in Bolivia. Commun Res. 1998;25:96–124. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hubbard R, Wald E. Exploding the gene myth: how genetic information is produced and manipulated by scientists, physicians, employers, insurance companies, educators, and law enforcers. Boston: Beacon Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelkin D, Lindee S. In: The DNA mystique: the gene as cultural icon. Freeman WH, editor. New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Public beliefs about schizophrenia and depression: similarities and differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(9):526–34. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.French DP, Marteau TM, Senior V, Weinman J. Perceptions of multiple risk factors for heart attacks. Psychol Rep. 2000;87(2):681–7. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.87.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Molster C, Charles T, Samanek A, O’Leary P. Australian study on public knowledge of human genetics and health. Public Health Genomics. 2009;12(2):84–91. doi: 10.1159/000164684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore T, Norman P, Harris PR, Makris M. An interpretive phenomenological analysis of adaptation to recurrent venous thrombosis and heritable thrombophilia: the importance of multi-casual models and perceptions of primary and secondary control. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:775–84. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parrott RL, Silk KJ, Condit C. Diversity in lay perceptions of the sources of human traits: genes, environments, and personal behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(5):1099–109. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tessaro I, Smith SL, Rye S. Knowledge and perceptions of diabetes in an Appalachian population. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(2):A13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walter FM, Emery J, Braithwaite D, Marteau TM. Lay understanding of familial risk of common chronic diseases: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):583–94. doi: 10.1370/afm.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McBride CM, Alford SH, Reid RJ, Larson EB, Baxevanis AD, Brody LC. Characteristics of users of online personalized genomic risk assessments: implications for physician–patient interactions. Genet Med. 2009;11(8):582–7. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181b22c3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hadley DW, Jenkins JF, Dimond E, de Carvalho M, Kirsch I, Palmer CG. Colon cancer screening practices after genetic counseling and testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):39–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lucke J, Hall W, Ryan B, Owen N. The implications of genetic susceptibility for the prevention of colorectal cancer: a qualitative study of older adults’ understanding. Community Genet. 2008;11(5):283–8. doi: 10.1159/000121399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanderson SC, Persky S, Michie S. Psychological and behavioral responses to genetic test results indicating increased risk of obesity: does the causal pathway from gene to obesity matter? Public Health Genomics. 2009 May 4; doi: 10.1159/000217794. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heshka JT, Palleschi C, Howley H, Wilson B, Wells PS. A systematic review of perceived risks, psychological and behavioral impacts of genetic testing. Genet Med. 2008;10(1):19–32. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815f524f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aspinwall LG, Leaf SL, Dola ER, Kohlmann W, Leachman SA. CDKN2A/p16 genetic test reporting improves early detection intentions and practices in high-risk melanoma families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(6):1510–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chao S, Roberts JS, Marteau TM, Silliman R, Cupples LA, Green RC. Health behavior changes after genetic risk assessment for Alzheimer disease: The REVEAL Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(1):94–7. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31815a9dcc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beery TA, Williams JK. Risk reduction and health promotion behaviors following genetic testing for adult-onset disorders. Genet Test. 2007;11(2):111–23. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Collins VR, Meiser B, Ukoumunne OC, Gaff C, St John DJ, Halliday JL. The impact of predictive genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: three years after testing. Genet Med. 2007;9(5):290–7. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31804b45db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kinney AY, Hicken B, Simonsen SE, et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance behaviors among members of typical and attenuated FAP families. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(1):153–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phillips KA, Jenkins MA, Lindeman GJ, et al. Risk-reducing surgery, screening and chemoprevention practices of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a prospective cohort study. Clin Genet. 2006;70(3):198–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rief W, Conradt M, Dierk JM, et al. Is information on genetic determinants of obesity helpful or harmful for obese people?—A randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1553–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0353-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roberts JS, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, et al. Genetic risk assessment for adult children of people with Alzheimer’s disease: the Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer’s Disease (REVEAL) study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18(4):250–5. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ersig AL, Williams JK, Hadley DW, Koehly LM. Communication, encouragement, and cancer screening in families with and without mutations for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: a pilot study. Genet Med. 2009;11(10):728–34. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181b3f42d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carpenter MJ, Strange C, Jones Y, et al. Does genetic testing result in behavioral health change? Changes in smoking behavior following testing for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(1):22–8. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frosch DL, Mello P, Lerman C. Behavioral consequences of testing for obesity risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(6):1485–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gable D, Sanderson SC, Humphries SE. Genotypes, obesity and type 2 diabetes—can genetic information motivate weight loss? A review. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45(3):301–8. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marteau T, Senior V, Humphries SE, et al. Psychological impact of genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia within a previously aware population: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;128A(3):285–93. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanderson SC, Michie S. Genetic testing for heart disease susceptibility: potential impact on motivation to quit smoking. Clin Genet. 2007;71(6):501–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sanderson SC, Humphries SE, Hubbart C, Hughes E, Jarvis MJ, Wardle J. Psychological and behavioural impact of genetic testing smokers for lung cancer risk: a phase II exploratory trial. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(4):481–94. doi: 10.1177/1359105308088519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Senior V, Marteau T, Weinman J. Impact of genetic testing on causal models of heart disease and arthritis: an analogue study. Psychology and Health. 2000;14:1077–88. doi: 10.1080/08870440008407368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smerecnik CM, Mesters I, van Keulen H, et al. Should individuals be informed about their salt sensitivity status? First indications of the value of testing for genetic predisposition to low-risk conditions. Genet Test. 2007;11(3):307–14. doi: 10.1089/gte.2007.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Persky S, Kaphingst KA, Condit CM, McBride CM. Assessing hypothetical scenario methodology in genetic susceptibility testing analog studies: a quantitative review. Genet Med. 2007;9(11):727–38. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e318159a344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jakicic JM, Otto AD. Treatment and prevention of obesity: what is the role of exercise? Nutr Rev. 2006;64(2 Pt 2):57–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Valente TW. Models and methods for innovation diffusion. In: Carrington PJ, Scott J, Wassterman S, editors. Models and methods in social network analysis. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 98–116. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Afifi T, Hutchinson S, Krouse S. Toward a theoretical model of communal coping in postdivorce families and other naturally occurring groups. Communication Theory. 2006;16:378–409. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM. Understanding health behavior change among couples: an interdependence and communal coping approach. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(6):1369– 80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lyons RF, Mickelson KD, Sullivan MJ, Coyne JC. Coping as a communal process. J Social Personal Relationships. 1998;15(5):579–605. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderlik MR, Rothstein MA. Privacy and confidentiality of genetic information: what rules for the new science? Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2001;2:401–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ames SL, McBride C. Translating genetics, cognitive science, and other basic science research findings into applications for prevention. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(3):277–301. doi: 10.1177/0163278706290407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kral TV, Faith MS. Influences on child eating and weight development from a behavioral genetics perspective. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(6):596– 605. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marti A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Martinez JA. Interaction between genes and lifestyle factors on obesity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67(1):1–8. doi: 10.1017/S002966510800596X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wardle J, Carnell S, Haworth CM, Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S, Plomin R. Obesity associated genetic variation in FTO is associated with diminished satiety. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(9):3640–3. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Faith MS. Behavioral science and the study of gene–nutrition and gene–physical activity interactions in obesity research. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(3S):S82–4. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bryan A, Hutchison KE, Seals DR, Allen DL. A transdisciplinary model integrating genetic, physiological, and psychological correlates of voluntary exercise. Health Psychol. 2007;26(1):30–9. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rieder MJ, Livingston RJ, Stanaway IB, Nickerson DA. The environmental genome project: reference polymorphisms for drug metabolism genes and genome-wide association studies. Drug Metab Rev. 2008;40(2):241–61. doi: 10.1080/03602530801952880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, et al. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1185–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Collins FS, Mansoura MK. The Human Genome Project. Revealing the shared inheritance of all humankind. Cancer. 2001;91(1S):S221–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1+<221::aid-cncr8>3.3.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Duster T. Medicine. Race and reification in science. Science. 2005;307(5712):1050–1. doi: 10.1126/science.1110303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bonham VL, Sellers SL, Gallagher TH, et al. Physicians’ attitudes toward race, genetics, and clinical medicine. Genet Med. 2009;11(4):279–86. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318195aaf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Christensen C, Grossman J, Hwang J. The innovator’s prescription. New York: McGraw Hill; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Carlson RJ. The disruptive nature of personalized medicine technologies: implications for the healthcare system. Public Health Genomics. 2009;12(3):180–4. doi: 10.1159/000189631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Consensus Report of the Institute of Medicine. 2009 Jun 30; http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/ComparativeEffectivenessResearchPriorities.aspx.

- 94.Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1650–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pezzoli K, Tukey R, Sarabia H, et al. The NIEHS Environmental Health Sciences Data Resource Portal: placing advanced technologies in service to vulnerable communities. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(4):564–71. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Furr-Holden CD, Smart MJ, Pokorni JL, et al. The NIfETy method for environmental assessment of neighborhood-level indicators of violence, alcohol, and other drug exposure. Prev Sci. 2008;9(4):245–55. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]