Abstract

Federal and state initiatives are aligning around the goal that by 2014 all Americans will have electronic health records to support access to their health information any time and anywhere. As a key health care provider, nursing data must be included to enhance patient safety, effectiveness, and efficiency of care that is patient-centric. The purpose of this study was to test the feasibility of abstracting, integrating, and comparing the effective use of a standardized terminology, the Omaha System, across software vendors and 15 homecare agencies. Results showed that the 2,900 patients in this study had an average of four problems on care plans, with interventions most frequently addressing surveillance (39%) and teaching (30%). Findings in this study support the feasibility of integrating data across software vendors and agencies as well as the usefulness for describing care provided in homecare. However, before exchanging data across systems data quality issues found in this study need attention. There was missing data for 10.8% of patients as well as concerns about the validity of using the problem rating scale for outcomes. Strategies for effective use of standardized nursing terminologies are recommended.

Keywords: Omaha System, community health nursing, patient record systems, electronic health record, computerized patient record, documentation, nursing records, home visits, home health care

The recent mandate by the Federal government requiring electronic health records (EHRs) for all Americans by 2014 has aligned previously disparate efforts from strategic to coordinated tactical plans. Nationally, the Office of the Coordinator of Health Information Technology spawned several public and private initiatives to develop use cases, apply standards for implementation and exchange of data, and set requirements for certification of EHR vendors.1 Consistent with this effort, Minnesota passed the Health Record Act that requires all health care providers to use interoperable EHRs by 2015 including the use of uniform standards and where possible, to select certified EHRs. Interoperability is the ability of two or more systems to exchange data accurately, securely, and verifiably so information is available where and when needed (http://www.ehealthinitiative.org/ ). The momentum for interoperable EHRs was based on reports by the Institute of Medicine indicating that use of interoperable EHRs could improve the accuracy and accessibility to patient information to enhance patient safety, effectiveness and efficiency of care that is patient-centric.2, 3 In addition, the ability to access aggregated data provides greater opportunities to evaluate and improve the health of populations. Nursing has a long history of development and recognition of standardized terminologies to support nursing practice,4 yet the requirement to use standardized nursing data is just beginning to emerge in federal initiatives.5 Use of standardized nursing terminologies is essential if the contribution of nurses to the health care system is to be identified and valued.

The American Nurses Association6 (ANA) recognizes 12 nursing terminologies and data sets, which if used effectively, can support the interoperability of nursing data to provide continuity of patient care across systems and settings. ANA recognition is based on research establishing the reliability, validity, and usefulness of the terminology in practice. Subsequent research focuses on use of a standardized language,7-12 however, no studies were found in which data from a standardized nursing terminology were abstracted from EHRs across agencies and software vendors. The majority of studies found abstracted data from paper records; others developed a data base that included standardized nursing terminologies for research or abstracted data from a single software vendor. Because of this, most studies have small sample sizes due to the labor costs of abstracting the data from a paper record or using a single setting. In addition, due to the number of different EHR vendors who may or may not used a standardized nursing language, accessing data related to nursing care from multiple organizations has been difficult. The purpose of this study was to test the feasibility of abstracting, integrating and comparing the effective use of a single nursing terminology across EHR vendors from multiple homecare agencies. Examining nursing data using a single terminology and a single type of setting provides a foundation for future studies regarding interoperability of nursing data using multiple terminologies and types of settings.

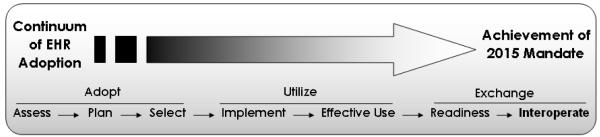

FRAMEWORK FOR INTEROPERABILITY

The Minnesota eHealth Advisory Committee developed a framework for “Adopting Interoperable Electronic Health Records”13 as shown in Figure 1. Adopting an interoperable EHR requires the use of multiple standards, including standardized nursing terminologies. The first step of the framework is Adopt, which requires users to assess their practice, plan for the use of standardized terminologies as part of an EHR, and select a vendor that supports their requirements. The second step is Utilize. As part of the implementation process, education about the use of an EHR also includes effective use of terminologies for documentation. The final step is Exchange, which is the sharing of data across information systems. Readiness for exchange of data requires the ability to abstract the data and evaluate the quality of the data prior to interoperability (routine sharing across information systems).

Figure 1.

Framework for “Adopting Interoperable Electronic Health Records†.”

†Minnesota Department Of Health (2008). http://www.health.state.mn us/e-health/ehrplan.html.

BACKGROUND

The Omaha System is one of the ANA recognized nursing terminologies and has the potential to support interoperability.6 The Omaha System is a comprehensive terminology for community-based practice and consists of the Problem Classification Scheme (nursing diagnoses), Intervention Scheme, and Problem Rating Scale for Outcomes. It was developed through 11 years of successive federal grants to establish the reliability, validity, and usability in multiple settings.14 The Omaha System addresses four domains: environmental, psychosocial, physiological, and health-related behaviors. Within these domains are 44 problems with signs and symptoms. Examples of physiological problems include vision, cognition, respiration, and pain. The Intervention Scheme consists of four categories of action: teaching, treatments, case management, and surveillance and 63 targets or foci. Examples include teaching about cardiac care of surveillance or nutrition. The Problem Rating Scale has three dimensions which are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale: knowledge, behavior, and status. In home care, the Omaha System is core within an EHR to conduct patient assessments, create care plans, document interventions, and evaluate outcomes. The published coding for the data allows for consistent implementation for comparison of the data across vendors and agencies.

In addition to meeting the ANA criteria for reliability, validity, and usefulness to describe nursing practice, the Omaha System is positioned to support interoperability through integration with other standards such as Health Level Seven (HL7®) and the Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP).15 The Omaha System is mapped to other standardized terminologies which can support exchange of data across a variety of practices and settings. Mapping of the Omaha System with other terminologies includes: the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine--Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT®), the Logical Observation Identifiers, Names and Codes (LOINC®), the National Library of Medicine’s Metathesaurus, and the ABC Codes. The problems and interventions also are mapped to the International Classification of Nursing Practice (ICNP®).16 While the Omaha System is poised to support interoperability, no studies exist that demonstrate the feasibility of abstracting, integrating and comparing the effective use of the data across vendors and multiple home care agencies.

Previous studies of the Omaha System have been conducted to describe the care of patients, evaluate practice, and predict resource use in home care agencies. For instance, Martin, Scheet, and Stegman17 conducted a study to describe homecare patients. They used a manual data collection form with 2,403 patients in four homecare agencies. The investigators found that patients had a mean of 3.79 problems, ranging from 1 – 15 problems per patient with 71% of problems associated with the physiological domain. Using a paired t-test, the investigators demonstrated that patients had an increase in knowledge, behavior, and status from admission to discharge, but only knowledge was statistically significant. There were 96,000 interventions provided; surveillance interventions were the most frequent, followed by health teaching, treatments, and case management. In another descriptive homecare study, Kane and Mahony18 used the Omaha System to describe client problems and the outcomes from 145 records of drug-exposed infants. They found Caretaking/ Parenting to be the most frequent problem, but the Omaha System did not prove to be sensitive to the differences in outcomes between infants. The Omaha System also has been used to evaluate home care practice or predict resources or outcomes in home care.19-23 One of the findings was that an increase in the number of nursing problems was associated with higher resource use.19, 22 Helberg’s study21 also supported the relationship between increased nursing interventions and resource utilization. Other studies focused on predicting outcomes. For instance, O’Brien-Pallas et al24 collected data on 366 patients to determine the amount of variation in outcomes. They found that, length of stay, and higher education of the nurse explained large variation in improved outcomes, while a higher number of medical diagnoses and nursing diagnoses as well as age was associated with poorer outcomes. Marek25 and Helberg26 demonstrated that the Omaha System nursing diagnoses significantly predicted outcomes of care which included discharge service and discharge condition status. While considerable research has been conducted using the Omaha System to describe and evaluate practice, predict resource use, and evaluate outcomes, no studies were found demonstrating interoperability of the Omaha System across vendors and homecare agencies. The next logical step toward interoperability of nursing terminologies was to abstract all Omaha System data elements across multiple home care agencies using different EHR software vendors.

METHODS AND DESIGN

The purpose of this study was to test the feasibility of abstracting, integrating and comparing the effective use of the Omaha System data across multiple software vendors and homecare agencies. This study is the first phase of analysis for a larger study that combines the Outcome and ASsessment Information Set (OASIS) and Omaha System data to develop predictive models for homecare outcomes. After obtaining approval from the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB), only two software vendors were found that used both the OASIS data for homecare and a standardized nursing terminology, which was the Omaha System. Data were requested for patients who received homecare services during 2004. The investigators were blinded to the selection of agencies to minimize the risk of identifying patients. The two software vendors were asked to select agencies based on the vendors’ perception of effective use of the EHR by the agencies. The software vendors contacted their customers (agencies), explained the study, and obtained a written agreement for participation in the study. The investigators provided an agreement form that met the IRB requirements. Participating agencies were required to be fully implemented in the use of both the Omaha System and OASIS data within the EHR by July 31, 2003, so they had six months experience using their EHR prior to the selection of data for 2004 patients. Of the eighteen agencies contacted, fifteen agreed to participate. The three who did not participate declined due to insufficient time or resources, concern about their inefficient use of the Omaha System, and difficulty obtaining board approval in a timely manner.

Data abstracted in this study included all homecare adult patients who received skilled homecare services in 2004 and had a minimum of two OASIS assessments, one for the start of an episode of care and one for the end of an episode of care. An episode of care was defined as a continuous time interval during which a patient received one or multiple homecare visits. The length of an episode of care could extend from a single day to multiple years. The first OASIS record for an episode was based on the date the assessment was completed for a “start of care” or “resumption of care” assessment and the episode ended based on the date when the patient was hospitalized, discharged, or died. If the patient continued on service, the date of the last OASIS recertification was used. Many patients had multiple episodes of care but only data for the first episode is reported in this paper.

Data Collection

Data for this study came from homecare agencies’ EHRs. The data were recorded as part of routine documentation in a comprehensive EHR which included the use of OASIS and Omaha System data sets. Nurses and other clinicians documented OASIS assessments at the times prescribed by the CMS rules.31 Omaha System interventions were expected to be documented each visit. Both software vendors used a client-server architecture, in which clinicians could use laptop computers in the field and update the central database, typically on a daily basis. Data were stored in agencies’ centralized databases on their own servers. After obtaining agreement from agencies, the vendors modified existing reports to create a limited data set. The CMS published file format was used for OASIS data,27 however, the patient and agency identifiers were limited to only include admission, discharge, and birth dates. For the Omaha System, data abstracted included the following fields: agency and patient identifiers; admission, visit, and discharge dates; and, Omaha System problems, intervention category and target, and and the problem rating scale knowledge, behavior, and status ratings at admission and discharge. Agencies ran the requested data retrievals and the software vendors obtained a copy of the resulting files. The files obtained from each agency were: 1) the OASIS data, 2) the Omaha System problems and interventions, and 3) the Omaha System problems and outcome ratings. The files were provided to the investigators by secure computer-to-computer file transfer or using the University of Minnesota Netfiles which supports secure internet transfer and storage of data.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was divided into two phases. In phase one, the OASIS data from all agencies were integrated into a single file. A new variable was created for the length of the patient’s homecare episode from dates in the start and end assessment records. The date the assessment was completed at the start of an episode and the date of the discharge/ transfer/ death field or for recertifications, the date the assessment was completed at the end of an episode were used. The Omaha System problems and interventions with visit date were integrated into a separate file. Finally, the Omaha System problems and problem rating scale for knowledge, behavior, and status with dates these were recorded were integrated into a third file. The Omaha System outcomes were created by subtracting the discharge rating from the admission rating for each problem. In phase two, comparability of the data were examined using descriptive statistics for Omaha System problems, interventions, and outcomes within and across agencies. Differences in missing data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and either a Pearson Chi-Square, independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for differences, depending on the level of measurement and distribution of the data. When data were missing the patient episodes of care were dropped from the particular analysis.

RESULTS

The results for this study are reported by the two phases noted previously.

Phase One: Feasibility of Integrating Data

The original OASIS data set included 18,967 assessments for 3,199 patients with OASIS data who had received homecare services at some point in 2004. The original OASIS assessments included any OASIS assessment for patients receiving care in 2004, including assessments occurring before 2004 and after 2004. All data was retained to maximize the number of records for analysis. After evaluating the quality of the OASIS data (publication in process), the files were grouped into episodes of care, resulting in 4,244 episodes of care for 2,900 patients. Only the first episode of care is reported in this study, which was the earliest OASIS records that could be paired as start and end episode records. As a result, the number of episodes was the same as the number of patients and at times, these words are used interchangeably.

There were differences in the data and file formats for the Omaha System data across vendors. For instance, the problem of Pain was stored by one vendor as “24.Pain” and as “24” by the other vendor. Another example was the category of action was stored as “IV. Surv” and as a “4” by the other vendor to indicate Surveillance. One vendor provided the data in a *.dbf format whereas the other provided it in an ASCII text file. Since both vendors consistently used the Omaha System coding the data could be made compatible to allow for merging different database formats and comparison across vendors was possible.

The Omaha System data were linked to the OASIS episodes of care and examined for the number and percent of episodes of care that contained both data sets. The agency and patient identifiers and visit date of the Omaha System data were used to link interventions and outcomes to the OASIS episodes. The original intervention file contained 989,772 Omaha System intervention records and 20,187 Omaha System outcome records. Interventions documented before the start of the first episode of homecare were linked to the first episode if they occurred five days prior to the start of the episode. This is consistent with CMS’ regulation that the OASIS assessment can be completed up to five days within the start of care. After matching intervention records to OASIS episodes, there were a total of 360,094 records. The same proces was used to match Omaha System outcomes to OASIS episodes using agency and patient identifiers and visit dates. The end result of matching OASIS episodes with Omaha problems and outcomes was a total of 13,053 records. A comparison was made of the number of patients with an episode of care based on the OASIS data with those who had Omaha System intervention data. The expectation was that patients had a minimum of 1 – 2 visits to complete the OASIS assessments for the start and end of an episode of care and hence would have at least two visits with Omaha System data. Table 1 shows the number of patient episodes based on the OASIS data, the number of episodes with Omaha System data and the percent of episodes missing Omaha System data.

Table 1.

Missing Data for Omaha System Problems by Agency

| Agency | % Missing Omaha System Data |

# Patients with OASIS Data |

# Patients Omaha System Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 0.0 | 275 | 275 |

| L | 0.0 | 231 | 231 |

| N | 0.0 | 486 | 486 |

| O | 0.0 | 181 | 181 |

| H | 0.5 | 196 | 195 |

| I | 1.7 | 345 | 339 |

| M | 4.2 | 191 | 183 |

| C | 7.3 | 165 | 153 |

| D | 9.6 | 94 | 85 |

| K | 10.2 | 166 | 149 |

| G | 14.8 | 88 | 75 |

| A | 32.1 | 249 | 169 |

| B | 64.7 | 133 | 47 |

| F | 74.6 | 63 | 16 |

| E | 91.9 | 37 | 3 |

|

| |||

| Total All Agencies | 10.8 | 2900 | 2587 |

Overall an average of 10.8% of patient episodes did not have Omaha System interventions. It appears that the major reason for missing data was based on the agency. This may be due to the dates of the first episodes. Agencies were invited to participate in the study if they had fully implemented both OASIS and the Omaha System data at least six months before the index year of 2004. When the data were selected, however, all data for a patient was obtained, even if the data were documented prior to 2004. The data were examined to determine if the first episode of care 1) started and ended before January 1, 2004, 2) started before January 1, 2004, but continued into 2004, or 3) started after January 1, 2004. There were significant differences in missing data by time. Episodes that started and ended before 2004 had 24% missing data, those that started before 2004 but continued an episode in 2004 had 15.1% missing data and those whose episodes started after 2004 had 7.3% missing data (p ≤ .001). The data also were examined to determine if the length of an episode would account for differences in missing data. Those episodes with missing data were significantly longer (median = 70 days, range 1 – 6354) than those without missing data (median = 32 days, range 1 – 6130, p < .001).

Phase 2: Description of the Homecare Population

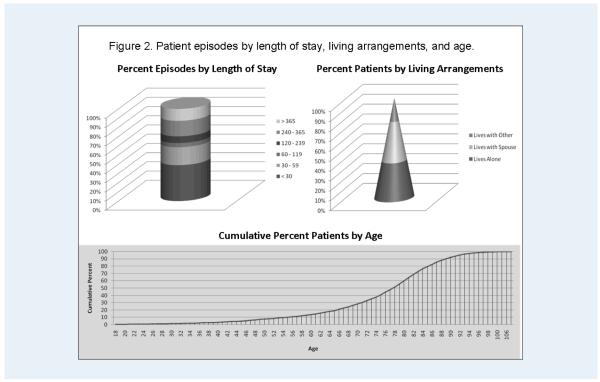

In phase two of the study, the Omaha System data were used to describe the problems, interventions, and outcomes of care within and across agencies. The majority of patients were white (97%) with 64% females. Most patients (75.5%) were discharged from an inpatient facility within 14 days prior to a homecare admission. Medicare (68%) and Medicaid (12%) were the major payors for homecare. A description of length of homecare episodes, patients’ living arrangements, and age is shown in Figure 2. Most patients were short-term patients with almost half (42%) of episodes lasting less than 30 days, with 64% of the admissions was less than 60 days. The majority of patients lived in their own residence (86%) with 38% living alone and 41% living with a spouse. As shown in Figure 2, 18% of patients were under the age of 65 and 39% were ages 75 to 84 with another 23% 85 years of age or older.

Figure 2.

Patients/ episodes by length of stay, living arrangements, and age.

Due to the large variation in specific primary medical diagnoses representing the reason for homecare, they were recoded into one of 260 clinical classification system (CCS) categories. The CCS categories are clinically meaningful groups for aggregating medical diagnoses developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.28 Based on expert consensus, the investigators further collapsed the 260 CCS categories into 51 groups. The most frequently occurring medical diagnosis (see Table 2) was abnormality of gait (14.7%) followed by congestive heart failure (4.8%), hypertension (4.4%), and other joint disorder (4.1%).

Table 2.

Most Frequent Primary Diagnoses Groups

| Description | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Other neurological diseases (93% abnormality of gait) | 427 | 14.7 |

| Congestive Heart Failure; non-hypertensive | 140 | 4.8 |

| Hypertension & other circulatory diseases | 128 | 4.4 |

| Other Joint Disorders | 119 | 4.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus with complications | 104 | 3.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus without complications | 100 | 3.4 |

| Osteoarthrosis | 99 | 3.4 |

| Other Respiratory | 94 | 3.2 |

| Acute cerebrovascular disease | 93 | 3.2 |

| COPD/ asthma | 92 | 3.2 |

| Fractures | 92 | 3.2 |

| Myocardial infarction | 90 | 3.1 |

Omaha System problems

There were 13,053 problems documented for all agencies, with a median of 4 problems per patient (ranging from 1 – 21). The most frequent problems by domain were: physiological (60%), other health related (35%), psychosocial (5%), and environmental (1%). All the Omaha System problems were documented at least once except for growth and development. The five most frequent problems on care plans accounted for 42.3% of all problems documented as shown in Table 3. For the five most frequent problems, there was variation by agency. Only neuro-musculo-skeletal (NMS) function and medication management were in the top five problems for all agencies. Circulation was a priority problem for 11 of the 15. The variation by agency may be due to the population served. Previous studies support that problems for CHF patients29 were different than those for mental health patients.30 Further analysis is needed to determine the variations in use of the Omaha System problems.

Table 3.

Most Frequent Omaha System Problems For All Agencies

| Omaha System Problem | Frequency | Percent All Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Neuro-musculo-skeletal function | 1,612 | 12.3 |

| Integument | 1,431 | 11.0 |

| Pain | 1,403 | 10.7 |

| Prescribed medication regimen | 1,211 | 9.3 |

| Circulation | 1,048 | 8.0 |

|

| ||

| Total | 6,705 | 43.3 |

Omaha System interventions

Interventions can be described and summarized in several ways; the category of action, a combination of category and target, or a combination of problem, category and target. There were 360,094 interventions documented for the first episode of care for all patients across all agencies. However, the category and target were missing for 16,801 (4.7%) interventions. The number and percent of interventions by category is shown in Table 4. The most frequent category of action was surveillance followed by teaching, guidance and counseling. These findings are similar to those in other studies, where patients were primarily community-based adults receiving nursing care.29, 31, 32

Table 4.

Interventions by Category.

| Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 4 – Surveillance | 133,539 | 38.9 |

| 1 - Teaching, guidance and counseling | 102,106 | 29.7 |

| 2 - Treatments and procedures | 80,571 | 23.5 |

| 3 - Case management | 27,077 | 7.9 |

|

| ||

| Total | 343,293 | 100.0 |

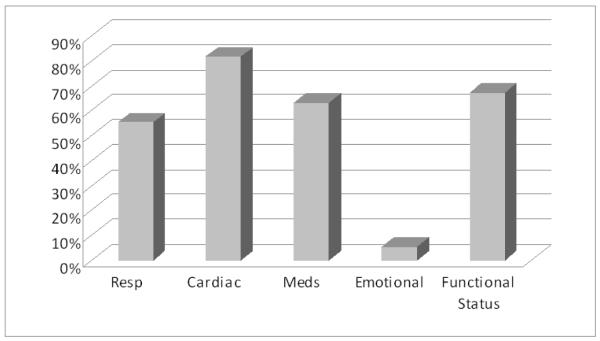

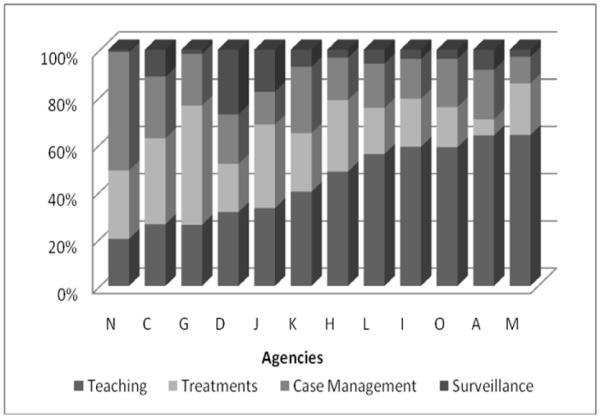

Since 3 of the 15 agencies had more than 50% missing intervention data, a comparison of interventions by intervention category included only 12 of the 15 agencies as shown in Figure 3. The interventions analyzed by category varied by as much as 26% to 44% across agencies. Further investigation is needed to determine if this difference is related to the type of patients or documentation practices of the agencies. Combining terms (problem, category, and target) to define an intervention resulted in many more types of interventions. The combination of intervention category and target resulted in 195 different combinations. The combined problem, category, and targets resulted in 1,145 different interventions.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the percent interventions by category and agency.

One of the goals for effective use of EHRs is to use evidence based practice and document care consistent with Medicare and other regulatory requirements. In homecare, this means that if the primary diagnosis is CHF, nurses would be expected to document problems, interventions and outcomes related to CHF. Based on previous research, the most frequent Omaha System problems for CHF patients included circulation, respiration, prescribed medication regime, emotional stability, and neuro-musculo-skeletal status.33 The percent of CHF patients with interventions by problem is shown in Figure 4. There were 125 of the 140 patients with CHF who had interventions documented for a total of 21,104 interventions. Ninety-one percent of patients had at least one intervention for Circulation (81.1%), Respiration (55.2%) or Medication management (63.2%). The problem of Emotional Status was addressed for only 5.6% of patients whereas 67.2% of the patients had interventions for Functional status (which includes interventions for multiple problems that include functional status signs and symptoms). The interventions for all problems combined resulted in 96% of CHF patients having at least one intervention addressing these priority problems

Figure 4.

Percent of CHF patients with interventions by problem.

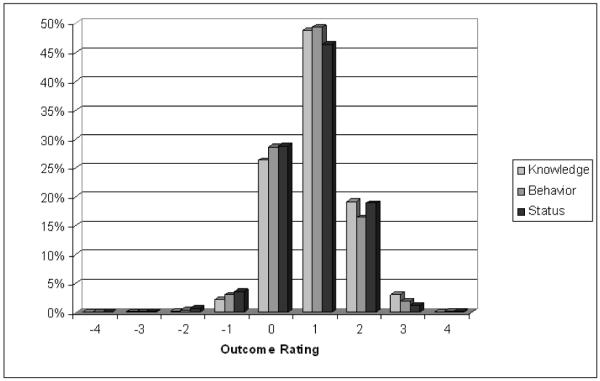

Omaha System outcomes

Outcomes were calculated for the Omaha System problem ratings for knowledge, behavior, and status by subtracting the admission rating from the discharge rating. Outcomes can range from a −4 to a +4 and are calculated only when both an admission and discharge rating existed. Of the 13,053 problems, 81.8% of problems had both admission and discharge ratings for calculating outcomes. The majority of patients improved in knowledge (66.8%), behavior (64.0%), and status (64.0%) for each of the top five problems shown in Table 3. There was a similar pattern of variation for each knowledge, behavior, and status outcome for all five problems in Table 3 across all agencies. The pattern was a normal distribution ranging from −3 to +4 and shown in Figure 5. The lack of any difference in outcome ratings for knowledge, behavior, and status by problem or agency raises concerns about the validity of the data and likely reflects documentation practices.

Figure 5.

Change in outcomes for top five problems.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to test the feasibility of abstracting, integrating and comparing the effective use of a single nursing terminology across EHR vendors from multiple homecare agencies. OASIS data were used to define episodes of care and describe patient demographics and medical diagnoses. The Omaha System data were linked to the OASIS episodes of care for homecare patients to describe problems, interventions, and outcomes. This study supported the feasibility of retrieving and integrating data across vendors and homecare agencies. When comparing the use of the Omaha System data, however, there were issues raised about the effective use of the terminology.

There were data quality issues discovered during the process of integrating the data across vendors and agencies. When linking Omaha System interventions and outcomes to OASIS episodes of care, there was considerable missing data with as much as 10.8% of patient episodes of care missing Omaha System interventions across all agencies. There were significant differences associated with the amount of missing data including the timing of the episode of care, length of the episode, agency, and vendor. Missing data in this study is less than that found by Stokke and Kalfoss34 where nursing interventions were missing in 18% of records and progress toward goals was missing 45% of the time. Experience with using the EHR was significantly related to missing data in this study as shown by episodes of care prior to 2004 had more missing data than those after 2004 when agencies were expected to have at least six months experience using the EHR. This supports finding in other studies that showed the longer an EHR is used, the more complete the documentation.35, 36

The results of this study demonstrate the usefulness of the Omaha system for describing practice in homecare. In this study, all problems in the Omaha system were addressed with the exception of growth and development. While growth and development is important issue across the lifespan, it likely is not a priority for an elderly population who primarily received services post-hospitalization. It is interesting to note that the use of the Omaha System findings in this study was most similar to Martin, Scheet, and Stegman’s17 study of homecare patients in 1993. Patients in both studies had an average of four problems with the majority of problems associated with the physiological domain. Both studies found surveillance interventions occurred most frequently followed by teaching, treatments, and case management. Both found that the problem rating outcome scale demonstrated improvements in knowledge, behavior and status for the majority of patients. However, in this study, there were problems identified with use of the problem rating scale. For the five most frequent problems in this study, there was little difference in the pattern of change from admission to discharge for knowledge, behavior, and status. It was expected that improvement in knowledge would precede behavior change and that changes in behavior or management or problems would precede changes in health status. The lack of discrimination in the pattern of outcomes likely reflects the way nurses document rather than valid outcomes and needs further investigation in future studies.

The investigators examined the consistency of documenting interventions for CHF patients. Ninety-one percent of patients had at least one intervention for problems expected to be documented as priorities for CHF patients: circulation, respiration, or medication management. This finding indicates that at least for CHF patients, there is consistency in the use of priority Omaha System problems for documenting interventions provided. Additional investigation is needed to look at consistency in documentation for other high volume conditions.

IMPLICATIONS

Based on the Framework for Adopting Interoperable EHRs presented earlier in this paper, the selection and implementation of a standardized nursing terminology must be included in the requirements for an EHR if nursing data are going to be interoperable in the future. Prior to exchange of nursing data, agencies must focus on the effective use of the terminology as part of implementation and training. There are several considerations for improving the effective use of nursing terminologies to support interoperability of nursing data. These include organizational changes, EHR optimization strategies, use of clinical decision support systems, and auditing the quality of the data recorded.

There are organizational interventions that staff and management can implement to improve the completeness, consistency, and appropriateness of documentation. For instance, staff education was demonstrated to improve the effective use of standardized terminologies for care planning to facility the handoff of care from one nursing shift to the next shift.37 Other investigators found that a combination of staff involvement in audit results from charts, collaboration on policies, and staff education improved documentation.38, 39

Optimizing EHRs to match the workflow of nurses and providing clinical decision support systems such as standardized care plans, templates, order sets, and alerts and reminders tools can improve documentation. For instance, the use of structured care plans was found to improve the number of nursing interventions and activities in long term care.40 Use of evidence-based protocols organized via the Omaha System framework for patients with medical diagnoses such as CHF, would not only improve documentation, but also would reflect the broader scope of nursing practice. Such documentation would provide data to support research in interventions for physiological, emotional, and functional problems. Additionally, collaboration across homecare agencies to develop care plans could improve consistency of care and documentation similar to the work in process by the Omaha System Users Group in Minnesota (K. Lindberg, personal communication, August 7, 2007). Vendors may provide a pathway or guideline tool that can guide the user to select care plans, thus improving compliance with agency recommended care.

Both the new essentials for baccalaureate and doctorate education for advanced practice require informatics as a core competency.6, 41, 42 While the use of nursing terminologies is not specifically stated in either document, the importance of technology to support nursing practice is identified. Nursing education across all levels of the curriculum should incorporate education about the ANA approved standardized nursing terminologies,6 how to use standardized terminologies for care planning and documentation, and methods to abstract data for purposes of quality improvement and research. Additionally, nurse educators need to emphasize the importance of standardized terminologies for interoperability. By 2014, it is anticipated that all Americans will have interoperable electronic health records. Unless nursing uses standardized terminologies, the ability to exchange important information for nurses will not be attained.

This study provides a first, and necessary step, to test the feasibility of integrating data across vendors and agencies and for comparing the effective use of homecare EHR standardized data representing the linkage of problems, interventions, and outcomes. While there were problems found in the completeness of documentation for nursing interventions and the potential validity of the outcomes, overall it was feasible to integrate the Omaha System and compare the use for documenting nursing problems, interventions, and outcomes. Use of the Framework for adopting Interoperable EHRs that includes nursing terminologies can improve the potential for interoperability of nursing data in the future.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a grant provided by the University of Minnesota Digital Technology Initiative and supported by CareFacts Information Systems and CHAMP Software. Dr. Westra is an owner in CareFacts Information Systems. It provided the foundational work for the foundation work for subsequent studies supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (Grant #P20 NR008992; Center for Health Trajectory Research). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Bonnie L. Westra, School of Nursing University of Minnesota 6-135 Weaver-Densford Hall 308 Harvard St SE Minneapolis, MN 55455 Tele - 612-625-4470 Fax - 612-626-3255 westr006@umn.edu.

Cristina Oancea, School of Nursing University of Minnesota 4-130 Weaver-Densford Hall 308 Harvard St SE Minneapolis, MN 55455 sco@cccs.umn.edu.

Kay Savik, School of Nursing University of Minnesota 6-111 Weaver-Densford Hall 308 Harvard St SE Minneapolis, MN 55455 Tele - 612-624-0405 Fax - 612-626-3255 savik001@umn.edu.

Karen Dorman Marek, College of Nursing University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee PO Box 413 Milwaukee, WI 53201-0413 414-229-5071 kmarek@uwm.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [Accessed October 26, 2008];Health Information technology

- 2.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine . To Err is Human: Building A Safer Health System. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westra BL, Delaney CW, Konicek D, Keenan G. Nursing standards to support the electronic health record. Nursing Outlook. 2008;56:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [Accessed October 26, 2008];AHIC Use Cases and Extensions/Gaps. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthit/usecases/

- 6.American Nurses Association [Accessed July 5, 2007];ANA Recognized Terminologies and Data Element Sets. Available at: http://nursingworld.org/npii/terminologies.htm.

- 7.Dochterman J, Titler M, Wang J, et al. Describing use of nursing interventions for three groups of patients. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37:57–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haugsdal CS, Scherb CA. Using NIC to describe the role of the nurse practitioner. Int J Nurs Terminol Classif. 2003;14:43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keenan G, Barkauskas V, Stocker J, et al. Establishing the validity, reliability, and sensitivity of NOC in an adult care nurse practitioner setting. Outcomes Manage. 2003;7:74–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keenan GM, Barkauskas V, Lee J, Stocker J, Treder M, Clingerman E. Evaluation of NOC measures in home care nursing practice. Int J Nurs Terminol Classif. 2003;14:50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Titler M, Dochterman J, Kim T, et al. Cost of care for seniors hospitalized for hip fracture and related procedures. Nurs Outlook. 2007;55:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowles KH. Use of the Omaha System in research. In: Martin KS, editor. The Omaha System: A Key to Practice, Documentation, and Information Management. 2nd ed Elsevier Saunders; St. Louis, MO: 2005. pp. 105–133. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnesota Department of Health and the Minnesota e-Health Initiative Advisory Committee [Accessed October 26, 2008];A Prescription for Meeting Minnesota′s 2015 Interoperable Electronic Health Record Mandate: A Statewide Implementation Plan. Available at: http://www.health.state.mn.us/e-health/ehrplan.html.

- 14.Martin KS. The Omaha System : A Key to Practice, Documentation, and Information Management. Elsevier Saunders; St. Louis: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin KS, Elfrink VL, Monsen KA. [Accessed October 26, 2008];The Omaha System: Solving the Clinical Data-Information Puzzle. Available at: http://www.omahasystem.org/

- 16.Hyun S, Park HA. Cross-mapping the ICNP with NANDA, HHCC, Omaha System and NIC for unified nursing language system development. Int Nurs Rev. 2002;49:99–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2002.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin KS, Scheet NJ, Stegman MR. Home health clients: Characteristics, outcomes of care, and nursing interventions. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1730–1734. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.12.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kane AT, Mahony DL. Issues in the integration of standardized nursing language for populations: A study of drug-exposed infants′ records. Public Health Nurs. 1997;14:346–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1997.tb00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hays BJ. Nursing care requirements and resource consumption in home health care. Nurs Res. 1992;41:138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hays BJ, Willborn EH. Characteristics of clients who receive home health aide service. Public Health Nurs. 1996;13:58–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helberg JL. Use of home care nursing resources by the elderly. Public Health Nurs. 1994;11:104–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1994.tb00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marek KD. Nursing diagnoses and home care nursing utilization. Public Health Nurs. 1996;13:195–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasquale DK. A basis for prospective payment for home care. Image J Nurs Scholarsh. 1987;19:186–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1987.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O′Brien-Pallas L, Irvine D, Murray M, et al. Evaluation of a client care delivery model, part 2: Variability in client outcomes in community home nursing. NURSING ECONOMICS$ 2002;20:13–21. 36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marek KD. PhD Dissertation. University of Wisconsin; Milwaukee: 1992. Analysis of the relationships among nursing diagnoses and other selected patient factors, nursing interventions and other measures of utilization, and outcomes in home health care. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helberg JL. Patients′ status at home care discharge. Image J Nurs Scholarsh. 1993;25:93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1993.tb00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid [Accessed October 1, 2006];Data Specifications. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/OASIS/04_DataSpecifications.asp.

- 28.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) [Accessed January 28, 2007];Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 29.Naylor, Bowles KH, Brooten D. Patient problems and advanced practice nurse interventions during transitional care. Public Health Nurs. 2000;17:94–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connolly PM, Mao C, Yoder M, Canham D. Evaluation of the Omaha System in an academic nurse managed center. ONLINE J NURS INFORM. 2006;10:14. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooten D, Youngblut JM, Deatrick J, Naylor M, York R. Patient problems, advanced practice nurse (APN) interventions, time and contacts among five patient groups. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erci B. Global case management: Impact of case management on client outcomes. Lippincotts Case Manag. 2005;10:32–38. doi: 10.1097/00129234-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naylor MD, Bowles KH, Brooten D. Patient problems and advanced practice nurse interventions during transitional care. Public Health Nurs. 2000;17:94–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stokke TA, Kalfoss MH. Structure and content in Norwegian nursing care documentation. Scand J Caring Sci. 1998;13:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nahm R, Poston I. Measurement of the effects of an integrated, point-of-care computer system on quality of nursing documentation and patient satisfaction. Comput Nurs. 2000;18:220–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larrabee JH, Boldreghini S, Elder-Sorrells K, et al. Evaluation of documentation before and after implementation of a nursing information system in an acute care hospital. Comput Nurs. 2001;19:56–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keenan G, Falan S, Heath C, Treder M. Establishing competency in the use of North American Nursing Diagnosis Association, Nursing Outcomes Classification, And Nursing Interventions Classification terminology. J Nurs Meas. 2003;11:183–198. doi: 10.1891/jnum.11.2.183.57286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoroddsen A, Ehnfors M. Putting policy into practice: Pre- and posttests of implementing standardized languages for nursing documentation. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1826–1838. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westra BL, Solomon D, Ashley DM. Use of the Omaha System data to validate Medicare required outcomes in home care. Journal of Healthcare Information Management. 2006;20:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daly JM, Buckwalter K, Maas M. Written and computerized care plans: Organizational processes and effect on patient outcomes. J Gerontol Nurs. 2002;28:14–23. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20020901-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Association of Colleges of Nursing [Accessed November 1, 2008];The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2011.04.009. Available at: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/Education/bacessn.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.American Association of Colleges of Nursing [Accessed November 1, 2008];The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice. Available at: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/DNP/pdf/Essentials.pdf.