Abstract

Purpose: The modulation of tissue hemodynamics has important clinical value in medicine for both tumor diagnosis and therapy. As an oncological tool, increasing tissue oxygenation via modulation of inspired gas has been proposed as a method to improve cancer therapy and determine radiation sensitivity. As a radiological tool, inducing changes in tissue total hemoglobin may provide a means to detect and characterize malignant tumors by providing information about tissue vascular function. The ability to change and measure tissue hemoglobin and oxygenation concentrations in the healthy breast during administration of three different types of modulated gas stimuli (oxygen∕carbogen, air∕carbogen, and air∕oxygen) was investigated.

Methods: Subjects breathed combinations of gases which were modulated in time. MR-guided diffuse optical tomography measured total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation in the breast every 30 s during the 16 min breathing stimulus. Metrics of maximum correlation and phase lag were calculated by cross correlating the measured hemodynamics with the stimulus. These results were compared to an air∕air control to determine the hemodynamic changes compared to the baseline physiology.

Results: This study demonstrated that a gas stimulus consisting of alternating oxygen∕carbogen induced the largest and most robust hemodynamic response in healthy breast parenchyma relative to the changes that occurred during the breathing of room air. This stimulus caused increases in total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation during the carbogen phase of gas inhalation, and decreases during the oxygen phase. These findings are consistent with the theory that oxygen acts as a vasoconstrictor, while carbogen acts as a vasodilator. However, difficulties in inducing a consistent change in tissue hemoglobin and oxygenation were observed because of variability in intersubject physiology, especially during the air∕oxygen or air∕carbogen modulated breathing protocols.

Conclusions: MR-guided diffuse optical imaging is a unique tool that can measure tissue hemodynamics in the breast during modulated breathing. This technique may have utility in determining the therapeutic potential of pretreatment tissue oxygenation or in investigating vascular function. Future gas modulation studies in the breast should use a combination of oxygen and carbogen as the functional stimulus. Additionally, control measures of subject physiology during air breathing are critical for robust measurements.

Keywords: breast cancer, optical imaging, MRI

INTRODUCTION

Tumor oxygenation has been a major area of interest in oncology research for decades because of its known links to disease severity and treatment outcome.1 Since hypoxic tumors are more aggressive, resistant to therapy, and prone to metastatic growth,2 the ability to increase their oxygenation has been investigated as a way to improve outcomes in acute treatments such as radiotherapy,3, 4, 5 hyperthermia,6 and photodynamic7 therapy. Methods to alter tumor tissue oxygenation and∕or to measure the induced changes would be powerful aids in the oncologic management of cancers.

One simple way to increase tissue oxygenation is to administer pure (100%) oxygen or carbogen (95% O2, 5% CO2) through a respiration mask. Unfortunately, the complexity of the body’s physiological response to the administration of these gases presents challenges to successful implementation. For example, although the delivery of 100% oxygen leads to an increase in arterial pO2 (as compared to breathing room air),8 the increased concentration in O2 causes the smooth muscle cells lining the vasculature to contract due to the lack of carbon dioxide in the blood.9 This condition, known as hypocapnia, causes the vascular resistance to increase, which decreases blood flow due to increased vascular constriction in the peripheral vascular bed.10, 11 This decrease in blood flow may induce local areas of hypoxia,11 counteracting the desired oxygenation change. Thus, tissue oxygenation may actually decrease during oxygen breathing; results are subject-specific and variable.4

To compensate for the loss in vascular tone during oxygen breathing, carbogen gas, which contains a large percentage of O2 mixed with a small concentration of CO2 (usually 1%–5%), can be used to limit vascular constriction.12, 9 Carbogen has been shown to increase both tissue blood flow8, 13 and tissue oxygenation14, 15, 16 compared to oxygen breathing. Increased tissue pO2 due to carbogen has been reported in the cerebrum,13 liver, spleen, paraspinal muscle, and subcutaneous fat.17

In tumors, carbogen breathing has a subject-dependent effect on tissue oxygenation, although in general it increases. For example, Martin et al.18 found a consistent increase both in median pO2 and in the ratio of pO2 measurements above vs below 10 mm Hg in head and neck tumors. On the other hand, although Falk et al. generally found an increase in tissue pO2, they also found a decrease or no increase in tumor oxygenation in four of 17 patients with a variety of tumors (including breast).

Some of these inconsistencies are likely attributable to the heterogeneity in tumor vascular density and function, due to such factors as vasoconstriction of feeding vasculature,19 anemic tumor vessels,20 and increased vascular permeability.1 These factors are inherent to neoplastic tissue and may account for poor oxygen delivery to the tumor during a respiratory stimulus. However, measurement sampling error caused by the small volume of tissue measured by oxygen microelectrodes or laser Doppler flow meters (typical instruments used to measure hemodynamics) may also contribute to the conflicting results found in the literature. Because tissues (especially tumors) are highly heterogeneous, these point measurements often give inconsistent results which are not necessarily indicative of the overall volumetric response.

Instead, diffuse optical techniques have been shown in to produce more consistent results16, 21 because they sample a much larger volume of tissue. This was demonstrated by Kim et al.,22 who measured changes in tissue hemodynamics in rat prostate tumors when inspired gas was switched from air to carbogen. They found consistent increases in tissue oxygenation with point-based near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measurements, while measuring heterogeneous changes in pO2 recorded by microelectrodes and 19F magnetic resonance (MR). Using similar NIRS techniques, Hull et al.23 noted decreased total hemoglobin (HbT) in rat mammary tumors, indicating a decreased blood flow, coinciding with increased oxygen saturation (Sat). Gu et al.24 also used point-based NIRS, and noted an increase in tumor oxyhemoglobin (HbO) due to carbogen (and also oxygen) breathing in rat mammary tumors with diffuse optical measurements.

This study measured the changes induced in the healthy human breast due to a respiratory stimulus with MR-guided diffuse optical imaging, which enabled the formation of images, instead of point measurements, of hemodynamics. We investigated the physiological response in normal tissue in order to understand the physiological response to inspired gases. This purpose was encouraged by conflicting reports in the literature on the vascular effects of carbogen breathing, including both increased25, 26 and decreased blood flow25, 27, 26 compared to air breathing. This technique allowed us to determine whether the oxygenation and hemoglobin changes are due to vascular tone or to the loading and unloading of oxygen from hemoglobin. In doing so, we utilize a modulated stimulus common in the functional MRI community. This approach differs from the techniques used in the studies reported above that monitor temporal changes because it can utilize techniques to analyze signal modulation. Thus, this approach is able to account for sampling error and separate hemodynamic changes in the presence of substantial background noise.

A final purpose of this study was to identify the gas combination that induced the most significant response in order to provide a means to control for intersubject physiological variations to the inspired gases. We investigated the response of total hemoglobin and hemoglobin oxygen saturation in the healthy breast through the control of three gas combination pairs: Air∕carbogen (Air∕Cb), air∕oxygen (Air∕Ox), and oxygen∕carbogen (Ox∕Cb). These gases were compared in order to determine if a consistently strong response could be measured for all subjects. The responses to these gas stimuli were related to a control experiment involving the inhalation of room air (in an identical air∕air delivery protocol) to assess the normal physiological variations in each subject. By determining the gas combination that produced the most robust changes, these results could serve as a baseline for studies of modulated gas breathing to characterize tumor vasculature. It also identified the extent of normal physiological changes in the breast, which could account for some of the variations exhibited in the literature. This information provides an additional benefit, in that it may be used to identify which subjects are more sensitive to oxygenation treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this paper reports the first systematic study of the volumetric response of total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation to externally controlled gas stimuli in the healthy human breast.

METHODS

MR-guided diffuse optical imaging

Diffuse optical imaging is a relatively new imaging modality that can be used to produce images of oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin (Hb), water fraction, and lipid content in breast tissue.28, 29 These concentrations are determined by fitting maps of light absorption at multiple wavelengths in the near infrared to known chromophore spectra.30 To accurately quantify tissue properties, the effects of light absorption and scatter on photon migration must be separated by either time or frequency domain measurements.31, 32 By operating within a MR scanner, images may be formed with increased accuracy and spatial resolution33 through the incorporation of prior knowledge of tissue boundaries, similar to one way in which computed tomography aids PET by providing structural details.34

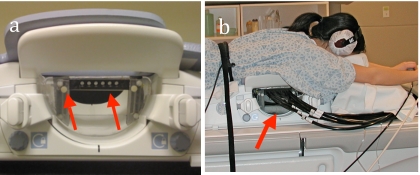

The MR-guided optical imaging instrument used in this work is shown in Fig. 1. This system coupled 16 optical fibers to the breast tissue through a custom-built nonmetallic interface.35 Light signals emitted from laser diodes at three wavelengths (661, 785, and 826 nm) were modulated at unique frequencies and combined at the source fiber, which was sequentially translated to 16 positions around the breast. Light was subsequently detected with photomultiplier tubes through the other 15 fibers. The details of the data acquisition scheme are described in more detail in Jiang et al.36 and McBride et al.37 Measurements of AC amplitude and phase shift were input into an iterative model-based reconstruction38, 39 to obtain images of breast hemodynamics in a single anatomically coronal slice every 30 s. This algorithm utilized the tissue boundaries defined by MR to influence the spatial distribution of contrast.40 The overall performance of the system is described more fully in Brooksby et al.41 In this study, a region-based method was used to determine hemodynamic properties in the adipose and fibroglandular tissue,40 which were identified through an MR water∕fat separated image.42 Fibroglandular regions were used for all analyses because this tissue contains the functional vascular tissue. Previous studies have determined that the spatial resolution of this system is about 5 mm for typical tumor contrasts.43

Figure 1.

(a) Photograph of the optical fiber holder incorporated into a biopsy attachment for an eight-channel breast coil (USA Instruments, Aurora, OH). Slots in the optical fiber holder allowed for vertical positioning of the optical fibers, while the biopsy attachment allowed positioning in the medical/lateral direction. These degrees of freedom in the fiber interface enabled the optical fibers to maintain contact with the breast. Arrows indicate the fiber holder and the vertical adjustment. (b) Photograph of a healthy subject with fibers attached to the MR coil. The arrow shows the fibers attached to the fiber holder.

Modulated gas breathing stimulus

The hemodynamics of breast tissue were monitored in 11 healthy volunteers during the modulation of three different inspired gas compositions: Oxygen(100% O2)∕carbogen(95% O2, 5% CO2), carbogen∕air(∼21%O2), and oxygen∕air. Air∕air was used as a control measure. We chose a 4 min (1∕240=0.0042 Hz) period for the breathing stimulus, alternating between the paired gas mixtures every 2 min, for a total of four complete cycles (16 min total acquisition). The gas stimulus combinations are shown in Fig. 2. Each image acquisition period was started within 1 min of the conclusion of the previous recording. The image data from the first alternating gas period were dropped after the gas combination pair was switched to ensure that lingering effects from the previous stimulus were minimized. All gas stimuli were not used with all volunteers because of MR scan-time limitations. The number of subjects who participated in the breathing experiments with a given gas stimulus is listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Gas timing diagram for the respiratory stimuli. Each stimulus alternated between two gases; the specifics of each stimulus is indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

The number of volunteers monitored with each gas stimulus pair.

| Gas 1 | Gas 2 | Number of subjects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus 1 | Air | Air | 11 |

| Stimulus 2 | Oxygen | Carbogen | 11 |

| Stimulus 3 | Air | Carbogen | 5 |

| Stimulus 4 | Air | Oxygen | 7 |

For the oxygen and carbogen gas stimuli, medical gases (Praxair) were directed from holding tanks into a respiratory circuit that controlled the source of inhaled gas while preventing the rebreathing of expired gases. As shown in Fig. 3, when the inlet valve from the gas tanks was opened, positive pressure from the feeding gas line closed the room air valve (preventing the breathing of room air). During the room air stimulus, the inlet valve from the gas tanks was closed (lack of inlet pressure from the gas tanks opened the room air valve). The switching of gases was controlled through a valve, driven by a computer running EPRIME software (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). Flow rates were maintained at 9 l∕min and were monitored by flow meters attached to the tanks.

Figure 3.

(a) Photograph of the gas breathing circuit placed on the MR table. (b) Schematic indicating that the carbogen and oxygen gases were controlled with a custom computer-controlled valve which was synchronized via software to maintain the desired modulation rate. (c) Diagram of circuit operation during gas stimulus. During oxygen or carbogen breathing, pressure from the inlet closes the valve to room air, preventing room air from entering the circuit. All valves were one-way. A fan in the MR bore was turned on to prevent rebreathing of expired gases. (d) Diagram of circuit operation during air stimulus. During air stimulus, the lack of pressure from the inlet opened the room air valve, allowing room air to be drawn into the circuit. A small tube was inserted near the mouthpiece to channel a small amount of expired air to an oxycapnometer to monitor exhaled gas concentrations.

Expired O2 and CO2 concentrations were continuously monitored during image acquisition to ensure subject compliance. A gas line attached to the breathing mask just below the mouthpiece led to an oxycapnograph (Capnomac Ultima, Helsinki, Finland), sampling the expired gas at 100 ml∕min. Analog signals from the oxycapnograph (CO2 and O2) were acquired using a data logger recording at 100 Hz (Measurement Computing, Norton, MA). All subjects had their noses sealed to ensure breathing through the mouthpiece.

All study participants provided informed consent and procedures were performed according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University Medical Center.

Data processing

Each point in the time series of data collection consisted of one optical image reconstruction. The data were calibrated with the first time point in a given stimulus series in order to reduce experimental noise from changes in fiber coupling, fiber attenuation, and other systematic errors.44 The calibrated data at the nth time point was calculated as

| (1) |

where is the measured data (i.e., phase and log amplitude) at the nth time point and and are the measured and calculated data (from a numerical fit of the optical properties to the data) from the first time point, respectively. This calibration routine is essentially the same as the one described in McBride et al.45 except that the reference recordings result from data collected at the initial time point in the breathing protocol rather than from a phantom. Data below the system noise floor were eliminated. The first breathing (4 min) period of each gas stimulus was also disregarded to remove physiological contributions from earlier gas stimuli. Thus, a full temporal data set consisted of 23 image acquisitions (2 images∕min×4 min∕period×3 periods−1 calibration image).

Cross correlations between the gas stimulus and the measured hemodynamic response in the breast were performed on the healthy fibroglandular tissue. Gas modulation was modeled with a sine wave at the stimulus frequency, shown in Fig. 2—An approximation which is reasonable because the vasculature acts as a temporal low pass filter.46, 47 The time course of the induced tissue response was median filtered and detrended before data processing. Cross correlation analyses were used to provide robust measures of the strength of correlation and the time lag between the gas stimulus and tissue response. The time lag at maximum correlation represented the lag in time between the gas stimulus and the tissue response and was calculated for total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation for each subject in this study.

To measure the strength of response in the breast due to the gas stimulus compared to each subject’s normal physiology, a signal to noise ratio (SNR) metric was calculated for total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation. The SNR was the ratio of the magnitude of the maximum correlation with the gas stimulus, to the maximum correlation with room air∕air breathing sequence

| (2) |

This measure yielded a method to determine which gas pair induced the strongest change and also served as a means to exclude data from the analysis when certain subjects did not measurably respond to a given gas stimuli. A SNR<1 was assumed to indicate that the gas stimulus did not induce a measurable change in breast physiology that was greater than the natural variations, which occur during a particular subject’s breathing of normal room air.

RESULTS

System stability

The optical system was tested for stability to ensure the acquisition of high quality images. These measurements were performed on a static, homogenous tissue-simulating phantom. Figure 4 shows the oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin concentrations recorded for this phantom. System noise caused fluctuations of less than 0.25% in its estimates of both of these quantities.

Figure 4.

Instrumentation related fluctuations in hemoglobin concentration recordings in a tissue-simulating phantom. Standard deviation in fitted deoxyhemoglobin is 0.19% of its amplitude while standard deviation in fitted HbO is 0.22% of its amplitude.

Time response in the healthy breast

A comparison of the total hemoglobin changes over time for a typical subject due to the oxygen∕carbogen stimulus [Figs. 5a, 5b] relative to the air∕air control [Figs. 5c, 5d) when SNR>1 are shown in Fig. 5. The corresponding oxygen saturation changes appear in Fig. 6. Compared to the control measurements, the oxygen∕carbogen gas stimulus induced a tissue response in total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation at the stimulus frequency [see Figs. 5b, 6b relative to Figs. 5d, 6d], which was greater than the physiological background in this subject. However, in some subjects, the physiological noise was greater than or equal to the induced gas response (i.e., SNR<1) as described in more detail in Sec. 3D.

Figure 5.

Temporal and frequency response of HbT for oxygen/carbogen gas stimulus compared to an air control in a typical subject where SNR>1. In (a), white bars indicate delivery of the O2 stimulus and gray bars symbolize carbogen administration, whereas in (c), both bars indicate the breathing of room air. Total hemoglobin oscillations during gas stimulus show a significantly larger peak at 0.0042 Hz, the stimulus frequency, than the air control [compare (b) vs (d)], indicating the tissue response to the stimulus was larger than the physiological noise. Oscillations in CO2 measured with the oxycapnograph during the oxygen/carbogen stimulus shown in (e) demonstrate subject compliance during the experimental protocol.

Figure 6.

Same as Fig. 5 for oxygen saturation.

Time lag response in healthy breast tissue

Time lag responses are shown in Fig. 7. These data are plotted in terms of phase lag ranging from 0 to 2π. Zero phase lag indicates a positive response to gas 1 with no delay whereas a phase lag of π indicates a positive response to gas 2 (see Fig. 2). Cases were excluded from the analysis (three with oxygen∕carbogen, one with the air∕carbogen, and four with the air∕oxygen) if the tissue response to the stimulus was less than the air control (i.e., SNR<1).

Figure 7.

Time lag comparison of Sat vs HbT for the three gas stimuli (in units of π). The stimuli with carbogen demonstrate vasodilation, a response that allows highly oxygenated blood to enter the breast tissue, thus washing out deoxygenated hemoglobin and increasing oxygen saturation. Oxygen saturation and total hemoglobin during air/oxygen stimulus is not dominated by changes in vascular tone. Instead, these changes may be influenced by changes in pO2. See Table 2 for summary.

The time lags between total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation demonstrate a significant linear correlation for the oxygen∕carbogen (r=0.91, p=0.0018, N=8) and air∕carbogen (r=0.96, p=0.039, N=4) stimuli. These results are consistent with the knowledge that carbogen induces vasodilation. Since vasodilation increases blood flow, freshly oxygenated arterial blood (∼98%–100% oxygenated) washes its deoxygenated counterpart out of the vasculature, increasing oxygen saturation.48 In the air∕oxygen case, oxygen saturation changes were independent of changes in total hemoglobin [as the variation in total hemoglobin (HbT) was not explained by the variation in oxygen saturation, p=0.82], although the sample size (N=3) is small (see Table 2). Thus, other factors besides vasomotor control appear to contribute substantially to the regulation of the hemodynamic response during the air∕oxygen stimulus. These changes are most likely due to variations in pO2, which induce changes in the loading and unloading of oxygen onto hemoglobin. Overall, these results indicate that the time delay in response is subject-dependent for both total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation which may be attributed to the physiological differences between each subject, as intersubject cardiac and vascular status influences blood gas delivery and exchange.49

Table 2.

Comparison of the correlation between oxygen saturation and total hemoglobin in breast fibroglandular tissue. Shown are the linear correlation coefficients, the significance, the coefficient of determination, and the number of subjects between oxygen saturation and total hemoglobin for each gas stimulus.

| Ox∕Cb | Air∕Cb | Air∕Ox | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r | 0.91 | 0.96 | −0.28 |

| p | 1.8×10−3 | 0.039 | 0.82 |

| R2 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.077 |

| N | 8 | 4 | 3 |

Noise considerations in the healthy breast

The body’s normal low frequency hemodynamic fluctuations are a confounding factor in the analysis of the data produced during this study. In some cases, these fluctuations had stronger spectral amplitude than the tissue response to the stimulus. By measuring the SNR between the response from the gas stimulus compared to the room air delivery, the gas stimuli can be evaluated for its effectiveness in inducing changes in breast vascular hemodynamics. Indeed, without properly accounting for the response of tissue during the room air breathing control, natural oscillations in hemodynamics could be mistakenly attributed to the gas stimuli.

These physiological fluctuations are frequency dependent. Previous investigators have noted that although the frequencies between 1 and 5 Hz have the largest variation (due to heart rate and respiration), significant oscillations in blood flow and blood pressure exist between 0 and 0.4 Hz.50 The frequency used in this study, 0.0042 Hz, coincides with the “very low” frequency range evaluated in spectral analyses of hemodynamics, which has been attributed to fluctuations in tissue metabolism.51

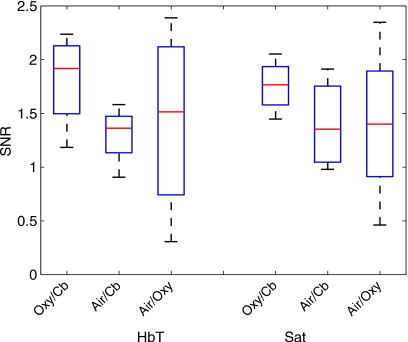

Box plots of the SNR for total hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation for each gas stimulus for all subjects are shown in Fig. 8. These results indicate that multiple subjects had a SNR<1. Of the three stimuli, the oxygen∕carbogen gas pair induced a response in oxygen saturation which was significantly stronger than the control (p=0.04, two-sample t-test, N=11). The response in total hemoglobin suggested a greater correlation than the control, although the result was not significant (p=0.06 two-sample t-test, N=11). In comparison, air∕carbogen was not significantly greater than the control for either total hemoglobin (p=0.30 two-sample t-test, N=5) or oxygen saturation (p=0.25 two-sample t-test, N=5). Air∕oxygen was also not significantly greater than the control for either quantity (HbT: p=0.49 two-sample t-test, N=7; Sat: p=0.33 two-sample t-test,N=7) (see Table 3 for more details).

Figure 8.

SNR in HbT concentration and Sat for each gas stimulus in fibroglandular tissue. ( *) denotes statistical significance. p-values and number of subjects in each group are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the correlation while breathing a gas stimulus compared to the correlation while breathing only room air (control) in breast fibroglandular tissue. Shown are the significance values resulting from two-sample t-tests, determining if the means were significantly different.

| Ox∕Cb: Control | Air∕Cb: Control | Air∕Ox: Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HbT | p=0.062, N=11 | p=0.297, N=5 | p=0.489, N=7 |

| O2 Sat | p=0.035, N=11 | p=0.251, N=5 | p=0.33, N=7 |

To compare the strength in correlation for all stimuli, SNR was compared for the four subjects who underwent all tests (N=4). Figure 9 shows that the mean SNR for the oxygen∕carbogen stimulus was higher than the other stimuli, although not significantly. The lack of significant differences between groups is most likely due to the small sample size in the face of relatively large intersubject variation, especially during the air∕oxygen stimulus.

Figure 9.

Average SNR for HbT and Sat for the four subjects who received all three gas stimuli. Error bars indicate the standard deviation in SNR for each gas combination.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the feasibility of inducing a measurable hemodynamic response in normal breast parenchyma during the breathing of controlled gas mixtures. The complex physiological changes that occur during the breathing of oxygen and carbogen were observed. The results obtained with diffuse optical imaging confirm the expectation that the response to gas stimuli with carbogen is dominated by changes in vasomotor control. These changes appear to override the effects of changes in pCO2 when the gas is switched to carbogen from air or oxygen (the latter would cause an opposite and negative change in oxygen saturation independent of total hemoglobin concentration due to the rightward shift in the oxygen dissociation curve48). In contrast, the response to an air∕oxygen stimulus is not dominated by vasomotor changes. Effects such as the change in oxygen saturation due to the change in pO2, which oppose the expected changes due to vasomotor control, seem to play a greater role in the modulation of total hemoglobin and oxygen saturation.

An important consideration in using any respiratory stimulus for either a diagnostic or a prognostic exam is choosing the optimal gas stimulus and∕or modulation frequency. These results show that significant changes can be induced in healthy breast tissue with an oxygen∕carbogen stimulus. Intuitively, the oxygen∕carbogen induced changes would be larger than those resulting from oxygen and room air or carbogen and room air because oxygen and carbogen induce opposing changes in vascular tone. Thus, a larger range in response would be expected from the pairing of oxygen∕carbogen as the gas stimulus. Our results support the expectation of an increase in SNR—The ratio between the hemodynamic response to the gas stimulus and the response during the breathing of room air. The responses to the oxygen∕carbogen stimulus were stronger than to air in both total hemoglobin (p=0.06) and oxygen saturation (p<0.05). In comparison, responses from the other gas stimuli did not demonstrate significant SNR>1 (p>0.2). Overall, SNR>1 was generated in 81% of the subjects breathing the oxygen∕carbogen combination, 80% of the volunteers breathing the air∕carbogen pair of gases, and only 64% of participants breathing the air∕oxygen stimulus.

An important consideration in this study was the modulation frequency. We chose the 0.0042 Hz oscillation frequency because it could be readily sampled with our instrumentation and because it has relatively low background physiological noise compared to other frequencies. In particular, this frequency regime (0–0.04 Hz) has lower physiological noise than the 0.04–0.15 Hz range.50 Higher frequencies intersect with cardiac and respiratory influences, which should be avoided in this measurement. Higher sampling resolution could have been realized with a lower stimulus frequency. However, the cost of using lower frequencies is longer experiment times and reduced subject compliance, yet this is logistically the most appropriate choice given the system performance.

In comparing SNR differences between stimuli, it is important to note that intersubject variance is high, especially for the air∕oxygen and oxygen∕carbogen stimuli. This variance cannot be attributed to aliasing from the cardiac or respiratory cycles, because each time point measurement consists of 16 source illuminations over a total of 30 s. In effect, this averages out any aliasing. Instead, the variance is better explained by intersubject variations in gas delivery and exchange.49 This variance may have led to a lack of significance of the air∕carbogen stimulus SNR measure, which has a relatively small subject population (N=5). The relatively large intersubject variance of air∕oxygen, coupled with the poorer tissue response, reveals an important distinction when modulating tissue hemodynamics with air∕oxygen. Carbogen seems to play a more active role in regulating hemodynamics than oxygen, as Fig. 7 indicates. Thus, in absence of an active carbogen stimulus, it may be expected that air∕oxygen modulates hemodynamics more poorly. It is important to recognize the limited population sizes in each group, which may have prevented statistical significance in the SNR comparison of Sec. 3D. However, although a larger subject population would have led to more confidence in identifying SNR differences between air∕oxygen and the other stimuli, these results in this work still hold merit in edifying the differences between these stimuli.

Efforts to elevate tissue oxygen levels for improved therapy sensitivity through the controlled breathing of gas mixtures has been under investigation for over 50 years.52 The ability to determine the sensitivity of a subject to these respiratory stimuli would have a significant impact on radiation treatment. In practice, the method described here could be used to screen for patients who would benefit from gas breathing to increase tissue oxygenation for therapy. For tumor detection, abnormal blood flow and oxygenation are known to be hallmarks of cancer.53 The modulation of respiratory gases may be a technique to probe tissue functional maturity.

CONCLUSIONS

This study presents the first reported measures of significant respiratory changes in the breast resulting from a respiratory stimulus. The data suggest that consistent physiological changes can be induced with the appropriate gas breathing stimulus, specifically, oxygen∕carbogen. Subjects who breathed the oxygen∕carbogen stimulus showed consistent (p<0.05) and significant (p<0.05) responses in total hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation determined via MR-guided diffuse optical tomography.

However, the data also indicate that these respiratory measurements can be affected by physiological noise. Even with the breathing stimulus having the strongest response signal, specifically, the oxygen∕carbogen gas pair, 19% of healthy volunteers had a SNR<1. The results highlight both the need for correct choice of breathing stimulus and the importance of monitoring normal physiological fluctuations as a control. If the technique is to be used for further proof of concept studies in tumor imaging or treatment response, use of the oxygen∕carbogen gas stimulus is recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to sincerely thank the funding sources: The Department of Defense Predoctoral Training Fellowship Grant No. 503298, the National Cancer Institute Grant Nos. 5P01CA080139 and 2R01CA069544, and the Center for Advanced Magnetic Resonance Technology at Stanford Grant No. P41 RR009784. The authors would also like to thank the generous efforts of Anne Sawyer, Dr. Bruce Daniel, and Dr. Brian Hargreaves.

References

- Vaupel P., Kallinowski F., and Okunieff P., “Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic macroenvironment of human tumors: A review,” Cancer Res. 49, 6449–6465 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizel D. M., Scully S. P., Harrelson J. M., Layfield L. J., Bean J. M., Prosnitz L. R., and Dewhirst M. W., “Tumor oxygenation predicts for the likelihood of distant metastases in human soft tissue sarcoma,” Cancer Res. 56(5), 941–943 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordsmark M., Bentzen S. M., Rudat V., Brizel D., Lartigau E., Stadler P., Becker A., Adam M., Molls M., Dunst J., Terriis D. J., and Overgaard J., “Prognostic value of tumor oxygenation in 397 head and neck tumors after primary radiation therapy. An international multi-center study,” Radiother. Oncol. 77(1), 18–24 (2005). 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans N. T. S. and Naylor P. F. D., “The effect of oxygen breathing and radiotherapy upon the tissue oxygen tension of some human tumours,” Br. J. Radiol. 36(426), 418–425 (1963). 10.1259/0007-1285-36-426-418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henk J. M., “Late results of a trial of hyperbaric-oxygen and radiotherapy in head and neck-cancer—A rationale for hypoxic cell sensitizers,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 12(8), 1339–1341 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank H., Loewe R., Loewe C., Oberhuber G., Schwaighofer B., Huber K., and Weissleder R., “Efficacy of thrombolytic therapy in pulmonary embolism determined by MION-enhanced MRA: An experimental study in rabbits,” Invest. Radiol. 33(12), 853–857 (1998). 10.1097/00004424-199812000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster T. H. and Gao L., “Dosimetry in photodynamic therapy—Oxygen and the critical importance of capillary density,” Radiat. Res. 130(3), 379–383 (1992). 10.2307/3578385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thews O., Kelleher D. K., and Vaupel P., “Dynamics of tumor oxygenation and red blood cell flux in response to inspiratory hyperoxia combined with different levels of inspiratory hypercapnia,” Radiother. Oncol. 62(1), 77–85 (2002). 10.1016/S0167-8140(01)00401-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton A. and Hall J., Textbook of Medical Physiology, 11th ed. (Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Eggers G. W. N., Warren J. V., Paley H. W., and Leonard J. J., “Hemodynamic responses to oxygen breathing in man,” J. Appl. Physiol. 17(1), 75–79 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Floyd T. F., Clark J. M., Gelfand R., Detre J. A., Ratcliffe S., Guvakov D., Lambertsen C. J., and Eckenhoff R. G., “Independent cerebral vasoconstrictive effects of hyperoxia and accompanying arterial hypocapnia at 1 ATA,” J. Appl. Physiol. 95(6), 2453–2461 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S., Miller W., and Eason J., Exercise Physiology: Basis of Human Movement in Health and Disease, 1st ed. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Ashkanian M., Borghammer P., Gjedde A., Ostergaard L., and Vafaee M., “Improvement of brain tissue oxygenation by inhalation of carbogen,” Neuroscience 156(4), 932–938 (2008). 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz B. A., “Adult and newborn rat inner retinal oxygenation during carbogen and 100% oxygen breathing—Comparison using magnetic resonance imaging Delta P-O-2 mapping,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 37(10), 2089–2098 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan B. F., Cron G. O., and Gallez B., “Rapid monitoring of oxygenation by 19F magnetic resonance imaging: Simultaneous comparison with fluorescence quenching,” Magn. Reson. Med. 61(3), 634–638 (2009). 10.1002/mrm.21594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer G. M., Viola R. J., Schroeder T., Yarmolenko P. S., Dewhirst M. W., and Ramanujam N., “Quantitative diffuse reflectance and fluorescence spectroscopy: Tool to monitor tumor physiology in vivo,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14(2), 024010 (2009). 10.1117/1.3103586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor J., Jackson A., Buonaccorsi G., Buckley D., Roberts C., Watson Y., Cheung S., McGrath D., Naish J., Rose C., Dark P., Jayson G., and Parker G., “Organ-specific effects of oxygen and carbogen gas inhalation on tissue longitudinal relaxation times,” Magn. Reson. Med. 58, 490–496 (2007). 10.1002/mrm.21357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L., Lartigau E., Weeger P., Lambin P., Le Ridant A. M., Lusinchi A., Wibault P., Eschwege F., Luboinski B., and Guichard M., “Changes in the oxygenation of head and neck tumors during carbogen breathing,” Radiother. Oncol. 27(2), 123–130 (1993). 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90132-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dische S., “What have we learnt from hyperbaric-oxygen,” Radiother. Oncol. 20, 71–74 (1991). 10.1016/0167-8140(91)90191-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A., Stewart F. A., Smith K. A., Soranson J. A., Randhawa V. S., Stratford M. R., and Denekamp J., “Effect of anemia on tumor radiosensitivity under normo and hyperbaric conditions,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 13(11), 1681–1689 (1987). 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90165-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. L., Song Y. L., Worden K. L., Jiang X., Constantinescu A., and Mason R. P., “Noninvasive investigation of blood oxygenation dynamics of tumors by near-infrared spectroscopy,” Appl. Opt. 39(28), 5231–5243 (2000). 10.1364/AO.39.005231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. G., Zhao D. W., Song Y. L., Constantinescu A., Mason R. P., and Liu H. L., “Interplay of tumor vascular oxygenation and tumor pO(2) observed using near-infrared spectroscopy, an oxygen needle electrode, and F-19 MR pO(2) mapping,” J. Biomed. Opt. 8(1), 53–62 (2003). 10.1117/1.1527049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull E. L., Conover D. L., and Foster T. H., “Carbogen-induced changes in rat mammary tumour oxygenation reported by near infrared spectroscopy,” Br. J. Cancer 79(11–12), 1709–1716 (1999). 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y., Bourke V., Kim J., Constantinescu A., Mason R. P., and Liu H., “Dynamic response of breast tumor oxygenation to hyperoxic respiratory challenge monitored with three oxygen-sensitive parameters,” Appl. Opt. 42(16), 2960–2967 (2003). 10.1364/AO.42.002960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell M. E., Hill S. A., Saunders M. I., Hoskin P. J., and Chaplin D. J., “Effect of carbogen breathing on tumour microregional blood flow in humans,” Radiother. Oncol. 41(3), 225–231 (1996). 10.1016/S0167-8140(96)01833-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzen J. L., Braun R. D., Ong A. L., and Dewhirst M. W., “Variability in blood flow and pO2 in tumors in response to carbogen breathing,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 42(4), 855–859 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn T. J., Braun R. D., Rhemus W. E., Rosner G. L., Secomb T. W., Tozer G. M., Chaplin D. J., and Dewhirst M. W., “The effects of hyperoxic and hypercarbic gases on tumour blood flow,” Br. J. Cancer 80(1–2), 117–126 (1999). 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride T. O., Pogue B. W., Gerety E., Poplack S., Osterberg U. L., and Paulsen K. D., “Spectroscopic diffuse optical tomography for quantitatively assessing hemoglobin concentration and oxygenation in tissue,” Appl. Opt. 38(25), 5480–5490 (1999). 10.1364/AO.38.005480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue B. W., Poplack S. P., McBride T. O., Wells W. A., Osterman S. K., Osterberg U. L., and Paulsen K. D., “Quantitative hemoglobin tomography with diffuse near-infrared spectroscopy: Pilot results in the breast,” Radiology 218(1), 261–266 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Zhang Q., Culver J., Miller E., and Boas D., “Reconstructing chromosphere concentration images directly by continuous-wave diffuse optical tomography,” Opt. Lett. 29(3), 256–258 (2004). 10.1364/OL.29.000256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson M. S., Moulton J. D., Wilson B. C., Berndt K. W., and Lakowicz J. R., “Frequency-domain reflectance for the determination of the scattering and absorption properties of tissue,” Appl. Opt. 30(31), 4474–4476 (1991). 10.1364/AO.30.004474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton E., Mantulin W. W., van de Ven M. J., Fishkin J. B., Maris M. B., and Chance B., “A novel approach to laser tomography,” Bioimaging 1, 40–46 (1993). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooksby B., Jiang S., Dehghani H., Pogue B. W., Paulsen K. D., Weaver J. B., Kogel C., and Poplack S. P., “Combining near infrared tomography and magnetic resonance imaging to study in vivo breast tissue: Implementation of a Laplacian-type regularization to incorporate MR structure,” J. Biomed. Opt. 10(5), 051504 (2005). 10.1117/1.2098627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang X., Wong W. H., Johnson V. E., Hu X., and Chen C. T., “Incorporation of correlated structural images in PET image reconstruction,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 13(4), 627–640 (1994). 10.1109/42.363105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C. M., Srinivasan S., Pogue B. W., Jiang S., Dehghani H., and Paulsen K. D., in Biomedical Optics, OSA Technical Digest (CD) (Optical Society of America, St. Petersburg, 2008), pp. BSuB4. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Pogue B., Laughney A., Kogel C., and Paulsen K., “Measurement of pressure-displacement kinetics of hemoglobin in normal breast tissue with near-infrared spectral imaging,” Appl. Opt. 48(10), D130–D136 (2009). 10.1364/AO.48.00D130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride T. O., Pogue B. W., Jiang S., Osterberg U. L., and Paulsen K. D., “A parallel-detection frequency-domain near-infrared tomography system for hemoglobin imaging of the breast in vivo,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 72(3), 1817–1824 (2001). 10.1063/1.1344180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arridge S. R., Scheiger M., and Delpy D. T., Inverse Problems in Scattering and Imaging (SPIE, San Diego, 1992), pp. 372–383. [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen K. D. and Jiang H., “Spatially varying optical property reconstruction using a finite element diffusion equation approximation,” Med. Phys. 22(6), 691–701 (1995). 10.1118/1.597488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani H., Pogue B. W., Shudong J., Brooksby B., and Paulsen K. D., “Three-dimensional optical tomography: Resolution in small-object imaging,” Appl. Opt. 42(16), 3117–3128 (2003). 10.1364/AO.42.003117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooksby B., Jiang S., Dehghani H., Pogue B. W., Paulsen K. D., Kogel C., Doyley M., Weaver J. B., and Poplack S. P., “Magnetic resonance-guided near-infrared tomography of the breast,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75(12), 5262–5270 (2004). 10.1063/1.1819634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder S., Pelc N., Alley M., and Gold G., “Multi-coil Dixon chemical species separation with an iterative least squares method,” Magn. Reson. Med. 51, 35–45 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.10675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue B. W., “Image analysis methods for diffuse optical tomography,” J. Biomed. Opt. 11(3), 033001 (2006). 10.1117/1.2209908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Springett R., Dehghani H., Pogue B. W., Paulsen K. D., and Dunn J. F., “Magnetic-resonance-imaging–coupled broadband near-infrared tomography system for small animal brain studies,” Appl. Opt. 44(10), 2177–2188 (2005). 10.1364/AO.44.002177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride T. O., Pogue B. W., Osterberg U. L., and Paulsen K. D., “Strategies for absolute calibration of near infrared tomographic tissue imaging,” Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 530, 85–99 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King R. B., Deussen A., Raymond G. M., and Bassingthwaighte J. B., “A vascular transport operator,” Am. J. Physiol. 265(6), H2196–H2208 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B. R., Belliveau J. W., Vevea J. M., and Brady T. J., “Perfusion imaging with NMR contrast agents,” Magn. Reson. Med. 14(2), 249–265 (1990). 10.1002/mrm.1910140211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J., Respiratory Physiology: The Essentials, 8th ed. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Brischetto M. J., Millman R. P., Peterson D. D., Silage D. A., and Pack A. I., “Effect of aging on ventilatory response to exercise and Co2,” J. Appl. Physiol. 56(5), 1143–1150 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo T. B. J., Chern C. M., Sheng W. Y., Wong W. J., and Hu H. H., “Frequency domain analysis of cerebral blood flow velocity and its correlation with arterial blood pressure,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 18(3), 311–318 (1998). 10.1097/00004647-199803000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Zhuo Y., Ye Y., Xie S., An J., Aguirre G., and Wang J., “Physiological origin of low-frequency drift in blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI),” Magn. Reson. Med. 61, 819–827 (2009). 10.1002/mrm.21902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach F. and Noell W. K., “Effects of oxygen breathing on tumor oxygen measured polarographically,” J. Appl. Physiol. 13(1), 61–65 (1958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl C., “The current status of breast MR imaging Part I, Choice of technique, image interpretation, diagnostic accuracy, and transfer to clinical practice,” Radiology 244(2), 356–378 (2007). 10.1148/radiol.2442051620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]