Abstract

Aims

We assessed regulation of volume-sensitive Cl− current (ICl,swell) by endothelin-1 (ET-1) and characterized the signalling pathway responsible for its activation in rabbit atrial and ventricular myocytes.

Methods and results

ET-1 elicited ICl,swell under isosmotic conditions. Outwardly rectified Cl− current was blocked by the ICl,swell-selective inhibitor DCPIB or osmotic shrinkage and involved ETA but not ETB receptors. ET-1-induced current was abolished by inhibiting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase or phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI-3K), indicating that these kinases were downstream. Regarding upstream events, activation of ICl,swell by osmotic swelling or angiotensin II (AngII) was suppressed by ETA blockade, whereas AngII AT1 receptor blockade failed to alter ET-1-induced current. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by NADPH oxidase (NOX) stimulate ICl,swell. As expected, blockade of NOX suppressed ET-1-induced ICl,swell, but blockade of mitochondrial ROS production with rotenone also suppressed ICl,swell. ICl,swell was activated by augmenting complex III ROS production with antimycin A or diazoxide; in this case, ICl,swell was insensitive to NOX inhibitors, indicating that mitochondria were downstream from NOX. ROS generation in HL-1 cardiomyocytes measured by flow cytometry confirmed the electrophysiological findings. ET-1-induced ROS production was inhibited by blocking either NOX or mitochondrial complex I, whereas complex III-induced ROS production was insensitive to NOX blockade.

Conclusion

ET-1–ETA signalling activated ICl,swell via EGFR kinase, PI-3K, and NOX ROS production, which triggered mitochondrial ROS production. ETA receptors were downstream effectors when ICl,swell was elicited by osmotic swelling or AngII. These data suggest that ET-1-induced ROS-dependent ICl,swell is likely to participate in multiple physiological and pathophysiological processes.

Keywords: Cell swelling, Cl− channel, Endothelins, Reactive oxygen species, VRAC

1. Introduction

Endothelins (ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3) are autocrine/paracrine signalling molecules and growth factors produced and released by vascular endothelium, cardiomyocytes, and other cells. Up-regulation of ET-1, the major cardiac myocyte isoform, is observed in cardiovascular disorders including congestive heart failure, myocardial ischaemia, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and sepsis-induced dysfunction.1 This peptide modulates cardiac contractile and electrical activity, and it is a potent mitogenic, fibrotic, and inflammatory factor that contributes to structural remodelling and triggers pro-survival signalling. ET-1 acts primarily via G protein-coupled ETA receptors, which are much more abundant on cardiomyocytes than ETB receptors.

The effects of ET-1 on cardiac electrical activity are complex. In atria, for example, ET-1 abbreviates action potential duration and modulates L-type Ca2+, ACh-activated K+, and inwardly rectifying K+ currents.2,3 Moreover, endothelins regulate the volume-sensitive Cl− current, ICl,swell. After first eliciting ICl,swell by osmotic swelling or hydrostatic inflation of atrial cells, Du and Sorota4 reported that ET-1 and ET-2 further augment the current, but the underlying signalling mechanisms are unknown.

Osmotic swelling and stretch of β1D integrins stimulate ICl,swell in ventricular myocytes via angiotensin II (AngII) AT1 receptors, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase, and phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI-3K) signalling that leads to production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by NADPH oxidase (NOX).5–8 Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) appears to be the active species; ICl,swell activation is reversed by catalase, and exogenous H2O2 elicits ICl,swell. ROS generated by NOX and exogenous H2O2 also stimulate ICl,swell in HeLa and haematoma cells,9,10 cultured primary astrocytes,11 and microglia.12

The signalling that triggers ICl,swell overlaps pathways implicated in the cardiac response to endothelin. Endothelins are downstream effectors for several actions of AngII,13–15 are released by mechanical stretch,14,15 and activate EGFR kinase16 and PI-3K.17 ROS production is also necessary for at least some of the endothelin-dependent responses in heart.18,19

We tested the hypothesis that ET-1 activates ICl,swell in atrial myocytes4 by the same pathway triggered by osmotic swelling and AngII in ventricular myocytes. We found that ET-1 elicited ICl,swell via ETA receptors under isosmotic conditions and that ETA receptors were downstream effectors for osmotic swelling- and AngII-induced ICl,swell. In contrast, ET-1–ETA receptors were upstream to EGFR kinase and PI-3K. Furthermore, ET-1-induced current and ROS production were fully inhibited by blocking either NOX or mitochondrial electron transport, whereas interventions that more directly augmented mitochondrial ROS production were insensitive to NOX inhibitors. Confirming results in atria, ET-1 evoked DCPIB-sensitive ICl,swell via ETA receptors and both NOX and mitochondrial ROS in ventricular myocytes. These data suggest that ET-1 regulates ICl,swell as part of a complex signalling cascade that ultimately triggers mitochondrial ROS production.

2. Methods

This study conforms to Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication 85-23, 1996) and was approved by Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (AM10290). Expanded Methods are available in Supplementary material online.

Atrial and ventricular myocytes were isolated from New Zealand white rabbits (2.8–3.4 kg) using collagenase (Cls 4) and pronase (Type XIV).5,6 Recordings were made in the whole-cell patch-clamp mode. Successive 500 ms steps were made from −60 mV to potentials between −100 and +60 mV in +10 mV increments, and current–voltage (I–V) relationships were plotted from quasi-steady-state currents.

ROS was detected by flow cytometry (EPICS XL; Beckman Coulter) of mouse atrial HL-1 cells loaded with C-H2DCFDA-AM (2.5 or 5 µmol/L), which primarily detects H2O2. This permitted analysis of cell populations and accurate cell-by-cell quantification of ROS production.

Solutions were designed to isolate Cl− currents. Isosmotic bath solution (300 mOsm/kg; 1T; T, times-isosmotic) contained (in mmol/L): 90 N-methyl-d-glucamine-Cl, 3 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 5 CsCl, 0.5 CdCl2, 70 mannitol (pH 7.4). Hypoosmotic (0.7T) and hyperosmotic (1.5T) bath solutions were made by omitting or adding mannitol. Standard pipette solution contained: 110 Cs-aspartate, 20 TEA-Cl, 5 Mg-ATP, 0.1 Tris-GTP, 0.15 CaCl2, 8 Cs2-EGTA, 10 HEPES (pH 7.1), and CsCl partially replaced equimolar Cs–aspartate in symmetrical Cl− pipette solution.

Data are reported as mean ± SEM; n denotes the number of cells for electrophysiology or experiments for flow cytometry. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA were performed and pairwise comparisons made by the Holm–Sidak method. Fluorescence histograms were analysed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks and compared with control by Dunn's method.

3. Results

3.1. ET-1 activates ICl,swell via ETA receptors

Figure 1A–C shows that ET-1 rapidly elicited an outwardly rectifying Cl− current in atrial myocytes in isosmotic solutions that reversed near the Cl− equilibrium potential, –43 mV. The ET-1-induced current was abolished by adding DCPIB, a highly selective ICl,swell inhibitor. Overall, ET-1 increased Cl− current at +60 mV from 0.54 ± 0.04 to 1.80 ± 0.10 pA/pF (n = 61, P< 0.01), and DCPIB blocked 99 ± 4% (n = 5, P< 0.01) of the increase. The half-time for activation was 5.1 ± 0.5 min (n = 9), and current was maintained for at least 45 min (n = 3). Furthermore, 95 ± 6% (n = 4, P< 0.01) of ET-1-induced current was inhibited by osmotic shrinkage in 1.5T bath solution containing ET-1 (Figure 1D–F). Complete suppression of the outwardly rectifying Cl− current with DCPIB and osmotic shrinkage indicates that ET-1 activated ICl,swell in atrial myocytes under isosmotic conditions and that prior stimulation by osmotic or hydrostatic swelling4 was not required. ET-1 also evoked an outwardly rectifying DCPIB-sensitive current in symmetrical Cl− media in atrial HL-1 myocytes,20 a characteristic diagnostic for ICl,swell.

Figure 1.

ET-1 activated ICl,swell in atrial myocytes under isosmotic (1T) conditions. (A and D) Families of currents before (Ctrl) and after exposure to ET-1 (10 nmol/L, 10 min) and after addition of DCPIB (10 µmol/L, 5 − 10 min) or osmotic shrinkage in 1.5T solution (5 − 10 min) in the presence of ET-1. (B and E) Current–voltage (I–V) relationships for (A) and (D), respectively. (Inset) Activation kinetics at +60 mV; t1/2, 5.1 ± 0.5 min (n = 9). (C and F) Currents at +60 mV in Ctrl, after ET-1, and after exposed to DCPIB (n = 5) or 1.5T (n = 4) in the presence of ET-1. **P < 0.01.

Stimulation of ICl,swell involved ETA rather than ETB receptors (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1). Exposure to BQ123 (10 µmol/L, 5–10 min), a selective ETA inhibitor, suppressed ET-1-induced currents by 90 ± 3% (n = 4, P < 0.01), whereas the selective ETB blocker BQ788 (100 nmol/L, 15–20 min) was ineffective (n = 4, NS).

Supplementary material online, Figure S2, shows that ET-1 also regulated ICl,swell in ventricular myocytes. The ET-1-induced current was 3.3 ± 0.4 pA/pF at +60 mV (n = 16, P< 0.01) and was fully suppressed by DCPIB (93 ± 6%; n = 4, P< 0.01). Moreover, the response to ET-1 was fully blocked by adding BQ123 (97 ± 2%; n = 4 P< 0.01), implicating ETA receptors in ventricular as well as atrial myocytes.

3.2. Role of ET-1 and ETA receptors in signalling

Stimulation of ICl,swell by β1D integrin stretch, osmotic swelling, or exogenous AngII in ventricular myocytes requires the sequential activation of AngII AT1 receptors, EGFR kinase, and PI-3K.5,7,8 Because AngII can act via ET-1 and ETA receptors13,19 and ET-1 activates EGFR kinase in cardiac myocytes,16 we tested the hypothesis that ETA receptors are upstream from EGFR kinase and PI-3K and downstream from AT1 receptors and osmotic swelling in the signalling pathway for ICl,swell. Figure 2A illustrates the effect of blocking downstream signalling in atrial myocytes. As predicted, selective inhibition of EGFR kinase with AG1478 suppressed ET-1-induced ICl,swell by 88 ± 3% (n = 5, P< 0.01), and exogenous EGF (10 nmol/L, 10 min) activated ICl,swell (n = 9, P< 0.01). Moreover, inhibiting PI-3K with LY294002 or wortmannin abrogated ET-1-induced current, blocking 102 ± 7% (n = 4, P< 0.02) and 92 ± 3% (n = 4, P< 0.01), respectively (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Atrial ET-1–ETA receptors were upstream from EGFR kinase and PI-3K and downstream from AngII AT1 receptors and osmotic swelling. (A) ET-1-induced ICl,swell (10 nmol/L, 10 min) was inhibited by the EGFR kinase blocker AG1478 (AG; 10 µmol/L, 10–15 min; n = 5) in the presence of ET-1, and EGF (10 nmol/L, 10 min; n = 9) elicited ICl,swell. (B) PI-3K blockers LY294002 (LY; 20 µmol/L, 10–15 min; n = 4) or wortmannin (Wort; 500 nmol/L, 10–15 min; n = 4) also inhibited ET-1-induced ICl,swell. (C) AngII-induced ICl,swell (5 nmol/L, 10 min; n = 5) was suppressed by BQ123. (D) AT1 blocker losartan (Los; 5 µmol/L, 15 min, n = 4) did not affect ET-1-induced ICl,swell. (E) Osmotic swelling-induced ICl,swell (0.7T, 5 min; n = 4) was reversed by BQ123. *P < 0.02; **P < 0.01.

The role of ETA receptors in responding to upstream signalling is depicted in Figure 2C–E. If ETA receptors are downstream from AT1 receptors, BQ123 should block AngII-induced ICl,swell, whereas the AT1 receptor blocker losartan should be ineffective in suppressing ET-1-induced ICl,swell. Consistent with this idea, AngII increased current at +60 mV from 0.40 ± 0.02 to 1.38 ± 0.24 pA/pF, and BQ123 blocked 92 ± 2% (n = 5, P< 0.01) of AngII-induced current in the presence of AngII. In contrast, the AT1 receptor blocker losartan did not alter ET-1-induced ICl,swell (n = 4, NS).

The proposed scheme also predicts that blockade of ETA receptors should suppress the activation of ICl,swell by osmotic swelling (Figure 2E). Osmotic swelling increased current at +60 mV from 0.67 ± 0.16 to 1.80 ± 0.42 pA/pF, and adding BQ123 to 0.7T solution blocked 91 ± 4% of swelling-induced current (n = 4, P< 0.01). In the presence of BQ123, both the swelling-induced current in 0.7T and AngII-induced current in 1T were indistinguishable from 1T control currents.

3.3. Reactive oxygen species

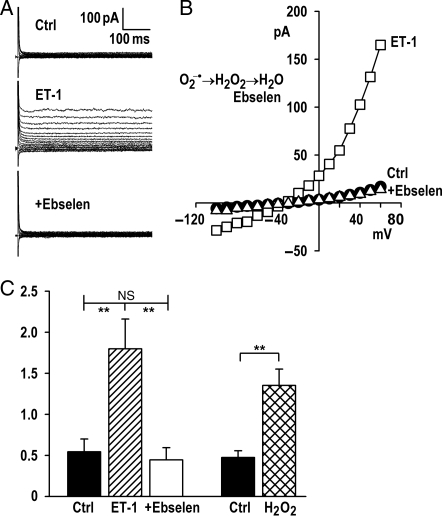

ICl,swell activation by stretch, osmotic swelling, AngII, and EGF requires ROS, and exogenous H2O2 elicits ICl,swell at a downstream site.5,7,8 To test whether ET-1 also utilizes ROS as a downstream effector in atrial myocytes, we used ebselen, a membrane-permeant glutathione peroxidase mimetic that scavenges H2O2. Figure 3 shows that the stimulation of ICl,swell by ET-1 was fully reversed by adding ebselen. Ebselen blocked 113 ± 10% (n = 4, P< 0.01) of ET-1-induced current. As expected if ebselen scavenges H2O2, exogenous H2O2 rapidly activated ICl,swell (n = 4, P< 0.01), as previous shown in the ventricle.5,7,8

Figure 3.

ICl,swell activation required ROS. (A) Currents and (B) I–V relationships before and after eliciting ICl,swell with ET-1 (10 nmol/L, 10 min) and after adding ebselen (15 µmol/L, 15 min), a glutathione peroxidase mimetic that dismutates H2O2. (C) Ebselen inhibited ET-1-induced current at +60 mV (n = 4), whereas H2O2 (100 µmol/L, 5 min) activated ICl,swell. **P < 0.01.

What is the source of ROS? One possibility is NOX. NOX subunit assembly and ROS production are stimulated by AngII, PI-3K, and ET-1,21,22 and block of NOX suppresses swelling- and stretch-induced ICl,swell in ventricular myocytes5,7,8 and other cells.9–12 To assess whether ET-1 depends on NOX to evoke ICl,swell, we used apocynin and the fusion peptide gp91ds-tat, two chemically distinct inhibitors of NOX assembly. Figure 4A–C demonstrates that adding apocynin suppressed 86 ± 6% (n = 5, P< 0.01) of ET-1-induced current in atrial myocytes, and current after block was not significantly different than control. Similarly, adding gp91ds-tat suppressed 101 ± 5% (n = 4, P< 0.01) of ET-1-induced ICl,swell (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Inhibiting either NOX ROS production with apocynin or gp91ds-tat or mitochondrial ROS production with rotenone fully blocked atrial ICl,swell. (A and D) Currents and (B and E) I–V relationships before and after exposure to ET-1 (10 nmol/L, 10 min) and after adding NOX inhibitor apocynin (Apo; 500 µmol/L, 10–15 min), or the mitochondrial complex I electron transport inhibitor rotenone (Rot; 10 µmol/L, 25–45 min) in the presence of ET-1. (C and F) Apocynin (n = 5), gp91ds-tat (gp; 500 nmol/L, 15 min; n = 4), and rotenone (n = 4) inhibited ET-1-induced ICl,swell. **P < 0.01.

Although these data implicate NOX as a required source of ROS in ET-1 signalling, NOX may not be a sufficient source. An important alternative is mitochondria, and the complex III Q cycle is a major site for extra-mitochondrial ROS release. Rotenone, a selective complex I inhibitor, suppresses electron flow to complex III and inhibits ROS generation by intact cardiac mitochondria. As shown in Figure 4D–F, adding rotenone to ET-1 blocked 85 ± 4% (n = 4, P< 0.01) of ET-1-induced current in atrial myocytes and restored current to its control value. ICl,swell evoked by ET-1 in ventricular myocytes also was fully abrogated by both gp91ds-tat (102 ± 0.8%, n = 4, P < 0.01) and rotenone (105 ± 0.8%, n = 4, P < 0.01), as shown in Supplementary material online, Figure S3. Finding inhibitors of NOX and mitochondrial ROS production both completely blocked ICl,swell suggests that these ROS sources are likely to act in series rather than by independent pathways.

To verify that mitochondrial ROS can activate ICl,swell, we used electron transport chain inhibitor antimycin A and the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel (mitoKATP) agonist diazoxide; both stimulate mitochondrial ROS production at complex III. As expected, if mitochondrial ROS participate, both antimycin A and diazoxide elicited atrial ICl,swell (Figure 5A and B). Antimycin A increased Cl− current at +60 mV from 0.54 ± 0.11 to 1.40 ± 0.14 pA/pF (n = 11, P< 0.01) and diazoxide from 0.60 ± 0.13 to 1.78 ± 0.47 pA/pF (n = 5, P< 0.02). Next, we tested whether production of ROS by NOX was downstream from mitochondrial ROS in the pathway regulating ICl,swell. Contrary to this idea, ICl,swell evoked by antimycin A and diazoxide was insensitive to two NOX blockers, apocynin (n = 5, NS) and the membrane-permeant fusion peptide gp91ds-tat (Figure 5A: n = 6, NS; Figure 5B: n = 5, NS). Taken together, Figures 4 and 5 suggest that mitochondria must be downstream from NOX in the ICl,swell signalling cascade.

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial ROS elicited ICl,swell and acted downstream from NOX and osmotic shrinkage. (A) Antimycin A (Anti; 10 µmol/L, 10 min) and (B) diazoxide (Diaz; 50 µmol/L, 10 min) augment ROS production by complex III, and both elicited ICl,swell. Mitochondrial ROS-induced ICl,swell was insensitive to two NOX blockers, apocynin (Apo; 500 µmol/L, 10 − 15 min; n = 5) and gp91ds-tat [500 nmol/L, 15 − 20 min; (A) n = 6; (B) n = 5]. (C–E) Currents and I–V relationship activated by antimycin and response to osmotic shrinkage (1.5T, 15 − 25 min) in the presence of antimycin. Osmotic shrinkage failed to suppress antimycin-induced ICl,swell (n = 4). **P < 0.01.

Osmotic shrinkage fully blocks ICl,swell elicited by exogenous ET-1 (Figure 1), EGF, and upstream signalling effectors, but shrinkage fails to reverse ICl,swell activation by exogenous H2O2, which is the furthest downstream regulator identified to date.8 Figure 5C–E demonstrates that mitochondrial ROS production elicited by antimycin A also was insensitive to osmotic shrinkage in 1.5T bath solution (n = 4, NS). These data imply that mitochondrial ROS production is a distal step in the cascade and is downstream to the site of action of osmotic shrinkage.

3.4. Measurement of ROS production

ET-1-induced ROS production was directly assessed in atrial HL-1 myocytes by flow cytometry after loading cells with C-H2DCFDA-AM, a fluorophore that senses H2O2. ET-1 itself was not fluorescent in the absence of the probe (Figure 6A and D). Basal ROS production (Ctrl) was detected in C-H2DCFDA-AM-loaded cells, and exposure to ET-1 significantly augmented fluorescence; exogenous H2O2 served as a positive control (Figure 6B and D). Importantly, pre-treatment with either rotenone or gp91ds-tat fully prevented ET-1-induced ROS production (Figure 6C and D), consistent with the idea that NOX and mitochondria must act in series. Flow cytometry also confirmed that antimycin A-induced mitochondrial ROS production was independent of NOX. Antimycin A increased ROS production 3.6-fold (n = 3, P< 0.05). After pre-treatment with gp91ds-tat, antimycin A still elevated ROS production 3.5-fold (n = 3, P< 0.05), whereas pre-treatment with rotenone decreased antimycin-induced ROS production to 1.2-times background (n = 3, NS). Thus, mitochondrial ROS production must be downstream from NOX, as also suggested by the electrophysiological data.

Figure 6.

ET-1-induced ROS production was inhibited by blocking either NOX or mitochondrial electron transport. Fluorescence (FL) histograms without (A) or with (B and C) C-H2-DCFDA-AM loading. (A) ET-1 was not fluorescent. (B) Basal ROS production (Ctrl) was increased by ET-1 (10 nmol/L, 10 min) or H2O2 (100 µmol/L, 10 min). (C) ET-1-induced ROS production was suppressed by pre-treatment with rotenone (Rot; 10 µmol/L) or gp91ds-tat (gp; 500 nmol/L). (D) Fold-increase in fluorescence from Ctrl (FL/FL0) for ET-1 (n = 9), ET-1 + Rot (n = 5), ET-1 + gp91ds-tat (n = 4), and H2O2 (n = 9). *P < 0.05, ANOVA on ranks. (E) Sigmoidal fit to kinetics of ET-1-induced ROS production (n = 5); t1/2, 9.5 ± 1.3 min, maximum FL/FL0, 6.1 ± 0.6. **P< 0.01 vs. Ctrl.

4. Discussion

Endothelins were initially reported to modulate ICl,swell after the current was first activated by osmotic swelling or hydrostatic inflation of atrial myocytes.4 We found that ICl,swell was also elicited by ET-1 via ETA receptors under isosmotic conditions in both atrial and ventricular myocytes, identified its position the signalling cascade, and demonstrated the involvement of ROS production by NOX and mitochondria. A diagram summarizing the ICl,swell cascade is presented in Figure 7. Although components of this pathway were known to regulate ICl,swell in cardiomyocytes, the role of ET-1 and obligatory mitochondrial ROS production was not previously recognized.

Figure 7.

Proposed ICl,swell signalling cascade. ET-1 elicited ICl,swell via ETA receptors. ET-1/ETA signalling was downstream from osmotic swelling and AngII AT1 receptors and was upstream from EGFR kinase, PI-3K, and ROS production. O2−• and/or H2O2 generated by NOX, most likely NOX2, stimulated mitochondrial (Mito) ROS production by complex III, and antimycin A and diazoxide augmented Complex III ROS production independent of NOX. The resulting H2O2 elicited ICl,swell, perhaps through intermediates. Ebselen scavenges H2O2 from NOX and/or mitochondria. Osmotic shrinkage inhibited the cascade upstream to complex III and, based on prior results in the ventricle, downstream to EGFR kinase. Interventions that stimulate (green) or suppress (red) ICl,swell. Activation (→), inhibition (⊥), and excluded pathways (×) are indicated.

Consistent with the proposed cascade, exogenous AngII5,8 and EGF7,8 elicited ICl,swell, and inhibitors of AT1 receptors, EGFR kinase, and PI-3K suppressed the current evoked by osmotic swelling6,8 or integrin stretch.5,7 ETA receptors must be downstream from osmotic swelling and AT1 receptors but upstream from EGFR kinase. Swelling- and AngII-induced ICl,swell was fully blocked by the ETA inhibitor BQ123. Moreover, ET-1-induced ICl,swell was blocked by suppressing EGFR kinase with AG1478 or PI-3K with LY294002 or wortmannin but was unaffected by the AT1 blocker losartan. Because integrin stretch activates ICl,swell via AT1 receptors, EGFR kinase, and PI-3K, it is likely but not proven that ETA receptors also participate in this pathway. A similar scheme for regulating ICl,swell may operate in other tissues. For example, EGF activates ICl,swell in HTC cells,10 and blocking PI-3K inhibits ICl,swell in pulmonary artery smooth muscle.23 Nevertheless, the proposed scheme may be an over simplification. We did not establish whether the response to swelling is due to an autocrine/paracrine release of endothelin and/or AngII or another mechanism. AT1 receptors appear to be activated by stretch in the absence of AngII binding,24 but an analogous mechanism has not been explored for ETA receptors. Alternatively, formation of AT1–ETA heterodimers might modulate crosstalk, as found for heterodimers between several G protein-coupled receptors.25 Src-dependent transactivation of ETA by AT1 reported in mesenteric arteries26 seems unlikely because blocking Src stimulates rather than inhibits osmotic swelling-induced ICl,swell in cardiac myocytes.5,27 Owing to the rapidity of the response, it also seems unlikely that osmotic swelling and AngII act by altering ET-1 synthesis. Finally, contributions from other branches of the signalling cascade triggered by ETA receptors and from feedback by ROS that modulates signalling cannot be excluded.

4.1. Reactive oxygen species

Activation of ICl,swell by swelling, stretch, AngII, and EGF has been attributed to ROS production by NOX in cardiac myocytes5,7,8 and other cells.9–12 H2O2 is thought to be the active ROS because ICl,swell activation is reversed by catalase and exogenous H2O2 elicits the current. ET-1-induced ICl,swell studied here must also depend on ROS production because it was suppressed by ebselen, a glutathione peroxidase mimetic that scavenges H2O2. Although NOX activity was required for ET-1 to elicit both ICl,swell and ROS production, we found that it was not a sufficient stimulus. Blocking either NOX with apocynin or gp91ds-tat or mitochondrial ROS production with rotenone fully suppressed both ET-1-induced ICl,swell and ROS production. This suggests that the NOX and mitochondria must have acted in series. If instead these ROS generators lead to independent paths, blocking only one would be expected to give partial inhibition. It seems likely that NOX was an upstream trigger for mitochondrial ROS production by complex III. Activation of ICl,swell was mimicked by augmenting mitochondrial complex III ROS production with antimycin A, an inhibitor of mitochondrial electron transport distal to the Qo site in complex III, or diazoxide, a mitoKATP channel opener. Furthermore, both the resulting current and ROS-induced fluorescence were insensitive apocynin and gp91ds-tat. Therefore, mitochondria must be downstream from NOX in the cascade activating ICl,swell.

Superoxide (O2−•) produced by NOX rapidly undergoes dismutation to H2O2, a longer-lived, membrane-permeant species. ROS may stimulate mitochondrial ROS production by several mechanisms. First, mitochondria can undergo ROS-induced ROS release, a process by which an initial release of ROS triggers oscillations of mitochondrial potential and ROS release that propagates from mitochondrion to mitochondrion.28,29 Although NOX has not been evaluated as a trigger for oscillatory ROS-induced ROS release, subsarcolemmal mitochondria are optimally positioned to respond to ROS generated by sarcolemma NOX. Secondly, membrane-permeant H2O2 acting on PKCε causes mitoKATP channels to open30 and thereby stimulates mitochondrial ROS production at complex III.31 A third possibility is that a signalosome, rather than free diffusion, delivers O2−• and H2O2 to mitochondria.30 Ligand binding to G protein-coupled receptors causes receptor internalization as part of multimolecular signalling complexes assembled in caveolae. Garlid et al.30 proposed such a mechanism to explain the coupling of multiple G protein-coupled receptor agonists to mitoKATP channels and complex III ROS production that underlies cardiac preconditioning. Although NOX was not included in the signalosome proposed by these authors, NOX is incorporated in agonist-induced early signalling endosomes in vascular smooth muscle cells and is an important source of O2−• and H2O2 in this setting.32

Both the NOX2 and NOX4 isoforms are expressed in cardiac myocytes.33 NOX4 is localized to endoplasmic reticulum in endothelial cells and to mitochondria in renal mesangial cells and cortex. It is likely, however, that only NOX2 is involved here. Downstream signalling by AngII depends on NOX2 but not on NOX4 in the heart.21,33 Moreover, both apocynin and gp91ds-tat act by preventing subunit assembly that is required for ROS production by NOX2. In contrast, NOX4 is generally considered constitutively active and is insensitive to subunit assembly blockers.33 Apocynin does not alter O2−• production by cardiac mitochondria34 but appears to inhibit P450 monooxygenase in endothelial cells.35 The fusion peptide gp91ds-tat36 is thought to be highly selective because it contains the 9-mer-binding site from gp91phox (NOX2) that associates with p47phox or its homologues (e.g. NOXO1, assembles with NOX1).

Rapid induction of cardiac NOX-dependent ROS production by ETA receptor activation initial was reported in cultured neonatal rat myocytes.37 Recently, mechanical stretch, AngII/AT1 receptors,38 and ET-1/ETA receptors39 also were shown to rapidly augment ROS production in cat ventricular myocytes by NOX- and mitochondria-dependent processes. These authors did not identify the interaction between the sources of ROS or the signalling cascade. Signalling regulating ROS production is highly tissue- and species-dependent, however. Whereas AngII-induced ROS produced in rat vascular smooth muscle peaks in 10 min, it takes 6 h when ETA receptors are stimulated with ET-1.40 In human vascular smooth muscle, AngII-induced activation of NOX is suppressed by apocynin, but blocking NOX has no effect on ET-1-induced ROS.41 Rather, ET-1-triggered ROS production was suppressed by inhibiting mitochondrial complex II with TIFT, complex IV with CCCP, but not blocking complex I with rotenone.

4.2. Implications

Thinking of ICl,swell as a current regulated by NOX and mitochondrial ROS rather than a current regulated by cell volume or stretch may help clarify its role. ROS production is augmented in a variety of physiological and pathophysiological settings, and up-regulation of ET-1 occurs in congestive heart failure, myocardial ischaemia, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and sepsis-induced dysfunction.1 We suspect that the same signalling cascade described here is likely to regulate ICl,swell in human cardiac disease, but to date only the involvement of EGFR kinase has been studied in atrial myocytes from patients.6 If ICl,swell is activated in human disease, it may influence outcomes by modulating action potential duration, cardiac cell volume, cell growth, and apoptosis. Moreover, in addition to ICl,swell, NOX and mitochondrial ROS production triggered by this signalling cascade are very likely to influence other ion channels and transporters in the heart.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Funding

This work was supported by grants to C.M.B. (American Heart Association grant 0855044E) and to Massey Cancer Center Flow Cytometry and Imaging Shared Resource Facility (National Institutes of Health grant P30CA16059).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Frances K.H. White and Julie Farnsworth for training and assistance in flow cytometry.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Brunner F, Bras-Silva C, Cerdeira AS, Leite-Moreira AF. Cardiovascular endothelins: essential regulators of cardiovascular homeostasis. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:508–531. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ono K, Tsujimoto G, Sakamoto A, Eto K, Masaki T, Ozaki Y, et al. Endothelin-A receptor mediates cardiac inhibition by regulating calcium and potassium currents. Nature. 1994;370:301–304. doi: 10.1038/370301a0. doi:10.1038/370301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiesecker C, Zitron E, Scherer D, Lueck S, Bloehs R, Scholz EP, et al. Regulation of cardiac inwardly rectifying potassium current IK1 and Kir2.x channels by endothelin-1. J Mol Med. 2006;84:46–56. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0707-8. doi:10.1007/s00109-005-0707-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du XY, Sorota S. Cardiac swelling-induced chloride current is enhanced by endothelin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;35:769–776. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200005000-00014. doi:10.1097/00005344-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. Angiotensin II (AT1) receptors and NADPH oxidase regulate Cl− current elicited by β1 integrin stretch in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:273–287. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409040. doi:10.1085/jgp.200409040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du XL, Gao Z, Lau CP, Chiu SW, Tse HF, Baumgarten CM, et al. Differential effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on volume-sensitive chloride current in human atrial myocytes: evidence for dual regulation by Src and EGFR kinases. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:427–439. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409013. doi:10.1085/jgp.200409013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. EGFR kinase regulates volume-sensitive chloride current elicited by integrin stretch via PI-3K and NADPH oxidase in ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:237–251. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509366. doi:10.1085/jgp.200509366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren Z, Raucci FJ, Jr, Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. Regulation of swelling-activated Cl current by angiotensin II signalling and NADPH oxidase in rabbit ventricle. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:73–80. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm031. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvm031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimizu T, Numata T, Okada Y. A role of reactive oxygen species in apoptotic activation of volume-sensitive Cl− channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6770–6773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401604101. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401604101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varela D, Simon F, Riveros A, Jorgensen F, Stutzin A. NAD(P)H oxidase-derived H2O2 signals chloride channel activation in cell volume regulation and cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13301–13304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400020200. doi:10.1074/jbc.C400020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haskew-Layton RE, Mongin AA, Kimelberg HK. Hydrogen peroxide potentiates volume-sensitive excitatory amino acid release via a mechanism involving Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3548–3554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409803200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M409803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrigan TJ, Abdullaev IF, Jourd'heuil D, Mongin AA. Activation of microglia with zymosan promotes excitatory amino acid release via volume-regulated anion channels: the role of NADPH oxidases. J Neurochem. 2008;106:2449–2462. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05553.x. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito H, Hirata Y, Adachi S, Tanaka M, Tsujino M, Koike A, et al. Endothelin-1 is an autocrine/paracrine factor in the mechanism of angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:398–403. doi: 10.1172/JCI116579. doi:10.1172/JCI116579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang F, Gardner DG. Autocrine/paracrine determinants of strain-activated brain natriuretic peptide gene expression in cultured cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14612–14619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14612. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.23.14612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cingolani HE, Alvarez BV, Ennis IL, Camilion de Hurtado MC. Stretch-induced alkalinization of feline papillary muscle: an autocrine–paracrine system. Circ Res. 1998;83:775–780. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.8.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kodama H, Fukuda K, Takahashi T, Sano M, Kato T, Tahara S, et al. Role of EGF Receptor and Pyk2 in endothelin-1-induced ERK activation in rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:139–150. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1496. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2001.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araki M, Hasegawa K, Iwai-Kanai E, Fujita M, Sawamura T, Kakita T, et al. Endothelin-1 as a protective factor against beta-adrenergic agonist-induced apoptosis in cardiac myocytes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1411–1418. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00822-6. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sand C, Peters SL, Pfaffendorf M, van Zwieten PA. The influence of endogenously generated reactive oxygen species on the inotropic and chronotropic effects of adrenoceptor and ET-receptor stimulation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2003;367:635–639. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0745-0. doi:10.1007/s00210-003-0745-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cingolani HE, Villa-Abrille MC, Cornelli M, Nolly A, Ennis IL, Garciarena C, et al. The positive inotropic effect of angiotensin II: role of endothelin-1 and reactive oxygen species. Hypertension. 2006;47:727–734. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000208302.62399.68. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000208302.62399.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng W, Raucci FJ, Jr, Baki L, Baumgarten CM. Regulation of volume-sensitive chloride current in cardiac HL-1 myocytes. Biophys J. 2010 1756-Pos (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrne JA, Grieve DJ, Bendall JK, Li JM, Gove C, Lambeth JD, et al. Contrasting roles of NADPH oxidase isoforms in pressure-overload versus angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2003;93:802–805. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000099504.30207.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park HS, Lee SH, Park D, Lee JS, Ryu SH, Lee WJ, et al. Sequential activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, βPix, Rac1, and Nox1 in growth factor-induced production of H2O2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4384–4394. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4384-4394.2004. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.10.4384-4394.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang GX, McCrudden C, Dai YP, Horowitz B, Hume JR, Yamboliev IA. Hypotonic activation of volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying chloride channels in cultured PASMCs is modulated by SGK. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H533–H544. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00228.2003. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00228.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou Y, Akazawa H, Qin Y, Sano M, Takano H, Minamino T, et al. Mechanical stress activates angiotensin II type 1 receptor without the involvement of angiotensin II. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:499–506. doi: 10.1038/ncb1137. doi:10.1038/ncb1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyngso C, Erikstrup N, Hansen JL. Functional interactions between 7TM receptors in the renin–angiotensin system—dimerization or crosstalk? Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.09.018. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaucage P, Iglarz M, Servant M, Touyz RM, Moreau P. Position of Src tyrosine kinases in the interaction between angiotensin II and endothelin in in vivo vascular protein synthesis. J Hypertens. 2005;23:329–335. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200502000-00015. doi:10.1097/00004872-200502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh KB, Zhang J. Regulation of cardiac volume-sensitive chloride channel by focal adhesion kinase and Src kinase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2566–H2574. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00292.2005. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00292.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1001–1014. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1001. doi:10.1084/jem.192.7.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Marban E, O'Rourke B. Synchronized whole cell oscillations in mitochondrial metabolism triggered by a local release of reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44735–44744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302673200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M302673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garlid KD, Costa AD, Quinlan CL, Pierre SV, Dos SP. Cardioprotective signaling to mitochondria. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:858–866. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.11.019. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forbes RA, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Diazoxide-induced cardioprotection requires signaling through a redox-sensitive mechanism. Circ Res. 2001;88:802–809. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.089342. doi:10.1161/hh0801.089342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller FJ, Jr, Filali M, Huss GJ, Stanic B, Chamseddine A, Barna TJ, et al. Cytokine activation of nuclear factor kappa B in vascular smooth muscle cells requires signaling endosomes containing Nox1 and ClC-3. Circ Res. 2007;101:663–671. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151076. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cave A. Selective targeting of NADPH oxidase for cardiovascular protection. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.10.001. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hool LC, Di Maria CA, Viola HM, Arthur PG. Role of NAD(P)H oxidase in the regulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel function during acute hypoxia. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:624–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.025. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pietersma A, de Jong N, de Wit LE, Kraak-Slee RG, Koster JF, Sluiter W. Evidence against the involvement of multiple radical generating sites in the expression of the vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Free Radic Res. 1998;28:137–150. doi: 10.3109/10715769809065800. doi:10.3109/10715769809065800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rey FE, Cifuentes ME, Kiarash A, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ. Novel competitive inhibitor of NAD(P)H oxidase assembly attenuates vascular O2− and systolic blood pressure in mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:408–414. doi: 10.1161/hh1701.096037. doi:10.1161/hh1701.096037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng TH, Shih NL, Chen SY, Wang DL, Chen JJ. Reactive oxygen species modulate endothelin-I-induced c-fos gene expression in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:654–662. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00275-2. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caldiz CI, Garciarena CD, Dulce RA, Novaretto LP, Yeves AM, Ennis IL, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species activate the slow force response to stretch in feline myocardium. J Physiol. 2007;584:895–905. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.141689. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.141689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Giusti V, Correa MV, Villa-Abrille MC, Beltrano C, Yeves AM, de Cingolani GE, et al. The positive inotropic effect of endothelin-1 is mediated by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Life Sci. 2008;83:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laplante MA, Wu R, Moreau P, de Champlain J. Endothelin mediates superoxide production in angiotensin II-induced hypertension in rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.11.026. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Touyz RM, Yao G, Viel E, Amiri F, Schiffrin EL. Angiotensin II and endothelin-1 regulate MAP kinases through different redox-dependent mechanisms in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1141–1149. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200406000-00015. doi:10.1097/00004872-200406000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.