Abstract

The majority of melanoma cells do not express argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS), and hence cannot synthesize arginine from citrulline. Their growth and proliferation depend on exogenous supply of arginine. Arginine degradation using arginine deiminase (ADI) leads to growth inhibition and eventually cell death while normal cells which express ASS can survive. This notion has been translated into clinical trial. Pegylated ADI (ADI-PEG20) has shown antitumor activity in melanoma. However, the sensitivity to ADI is different among ASS(−) melanoma cells. We have investigated and reviewed the signaling pathways which are affected by arginine deprivation and their consequences which lead to cell death. We have found that arginine deprivation inhibits mTOR signaling but leads to activation of MEK and ERK with no changes in BRAF. These changes most likely lead to autophagy, a possible mechanism to survive by recycling intracellular arginine. However apoptosis does occur which can be both caspase-dependent or independent. In order to increase the therapeutic efficacy of this form of treatment, one should consider adding other agent(s) which can drive the cells toward apoptosis or inhibit the autophagic process.

Keywords: Arginine deiminase, argininosuccinate synthetase, melanoma

INTRODUCTION

It has been known for years that certain cancers are auxotrophic for particular nonessential amino acids. By exploiting the differences between normal human cells and cancer cells, one can target these cancers and potentially reduce the side effects of the drugs. The best example so far has been the use of asparaginase in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). ALL cells have a requirement for L-asparagine, a nonessential amino acid in humans. By depleting this amino acid using asparaginase, ALL cells can be targeted and drug toxicity reduced.

BACKGROUND

Reversible inhibition of mitosis in lymphocytes cultures by mycoplasma was first noted by Copperman and Morton in 1966 [1]. The mechanism behind mycoplasma inhibition of lymphocyte transformation was later found to be due to arginine deprivation [2]. It was not until 1990 that Sugimura identified arginine deiminase as the lymphocyte blastogenesis factor originating from Mycoplasma arginini [3–5]. In the same year Miyazaki et al. reported on the potent growth inhibition of human tumor cells in culture by arginine deiminase purified from culture medium infected with mycoplasma [6]. Later, Takaku described the in vivo antitumor activity of arginine deiminase [7, 8] in melanoma cell lines.

Why Some Tumor Cells are Sensitive to Arginine Deprivation by Arginine Deiminase?

The amino acid arginine is involved in several important cellular functions. These include polyamine synthesis, creatine production and nitric oxide production [9–11]. Arginine is the only endogenous source of nitric oxide in humans [9]. In adult humans, arginine is considered a nonessential amino acid since it can be synthesized from citrulline. However, endogenous production of arginine may be insufficient under certain circumstances such as cell proliferation or wound healing. In tumor cells with high proliferation rate, exogenous arginine is required for their growth. Subsequently, it was discovered that melanoma cells are more sensitive to arginine deprivation.

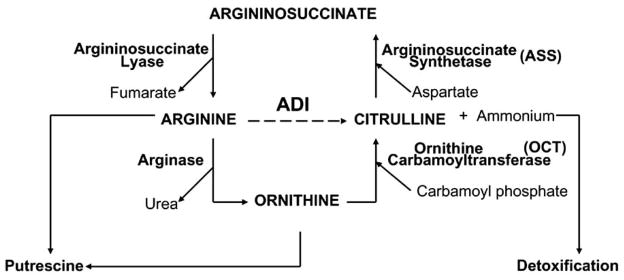

Arginine is synthesized from citrulline via the urea cycle (see Fig. 1). There are two key enzymes involved: (i) argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS) which converts L-citrulline and aspartic acid to argininosuccinate and (ii) argininosuccinate lyase (ASL) which then converts argininosuccinate to L-arginine and fumaric acid. L-arginine can also be degraded by the urea cycle enzyme arginase to L-ornithine. L-ornithine is converted back to L-citrulline by ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OCT) and then is recycled back to arginine. Wheatley has suggested that ASS and ASL are tightly coupled [12–14]. The sensitivity of tumor cells to arginine deprivation may depend on their ability to synthesize arginine from alternative intermediates in the urea cycle such as citrulline.

Fig. 1.

Enzymes in urea cycle. The dotted line represents the conversion of arginine to citrulline by ADI, a mycoplasma enzyme.

We and others have shown that melanoma cells do not express argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS) and hence are very sensitive to arginine deprivation. Treatment with arginine deiminase inhibits growth and induces cell death in melanoma cells [15–17]. In tumor or normal cells which possess ASS, treatment with ADI results in no growth inhibitory effects. In fact, transfection of ASS mRNA in melanoma cells results in resistance to ADI treatment [16, 17]. This concept has been exploited to treat tumor cells which lack ASS.

Which Arginine Degrading Enzyme Should be Chosen to Degrade Arginine?

There are three enzymes which can catabolize arginine: arginase, arginine decarboxylase and arginine deiminase (ADI). Arginase has a low affinity for arginine, and larger amounts of the enzyme may be required to produce a response. Furthermore, for arginase the optimal pH is 9.5 which is higher than the physiological value. On the other hand, Wheatley has shown that arginase may be effective at lower pH of 7.2 to 9 [18]. It is important to note that arginase catabolizes arginine to ornithine. The liver and small bowel are known to be able to convert ornithine to citrulline due to the presence of OCT. It is not clear whether other normal tissues are able to do this since OCT gene is hypermethylated and not expressed in other normal tissues. Thus, there is the potential for normal tissue toxicity from the use of arginase. Despite these potential problems, pegylated arginase has been shown to have both in vitro and in vivo activity in hepatocellular carcinoma [19, 20]. Arginine decarboxylase converts arginine to agmatine, which cannot be converted back to arginine and is relatively toxic to normal cells. Therefore, arginine decarboxylase is less favorable. Arginine deiminase degrades arginine to citrulline and ammonia. Tumor cells which lack ASS expression will not be able to synthesize arginine from citrulline while normal cells are able to do so. Thus, normal tissue toxicity can be avoided by this approach. Another advantage is that ADI is active at physiological pH and, unlike arginase, has high affinity for arginine [21]. The major drawback for ADI is that it is not a normal human enzyme but of mycoplasma origin. Therefore, ADI is highly immunogenic and has a short half-life. One method to prolong the half-life of the enzyme and reduce immunogenecity is by pegylation. A number of pegylated forms of ADI have been tested. One pegylated form of ADI has been developed by Polaris, Inc. (formerly Phoenix Pharmacologics) termed ADI-PEG20. After extensive toxicology testing, ADI-PEG20 has entered clinical trial, and antitumor activity has been seen in melanoma and hepatocellular carcinoma [22–26].

Arginine Deprivation Affects mTOR Signaling

Although arginine is a nonessential amino acid in normal cells which possess ASS; however, in ASS(−) tumor cells, it becomes an essential amino acid. Arginine deprivation inhibits mTOR, similar to that reported with nutritional deprivation or leucine (essential amino acid) deprivation. We have found that upon arginine deprivation, ASS(−) cells activate AMPK, which is known to regulate mTOR activity via energy/nutrient sensing [27–29]. When cells are deprived of ATP (high AMP/ATP ratio), AMPK is activated through phosphorylation by LKB or other upstream kinase(s) [30, 31]. Activated AMPK down regulates energetically demanding processes like translation by inhibiting mTOR [29]. In this regard, we have studied the effects of ADI-PEG20 treatment on ATP levels and AMPK activation. Our data showed that the ATP decreased by 30–60% at 72 h in 4 melanoma cell lines tested (Mel1220, A2058, SK-Mel-2 and A375). However, there are no changes in LKB level [16]. Thus, other upstream kinases may be involved. Activation of AMPK results in mTOR inhibition as evidenced by decreased 4E-BP phosphorylation, while p70S6K phosphorylation shows a decrease in 3 cell lines, but increase in one cell line in which ASS can be induced (A2058) [16]. It is possible p70S6K is phosphorylated by other upstream kinases. Our data demonstrated that upon arginine deprivation in ASS(−) melanoma cells, activation of AMPK occurs which in turn has a negative impact on mTOR activity.

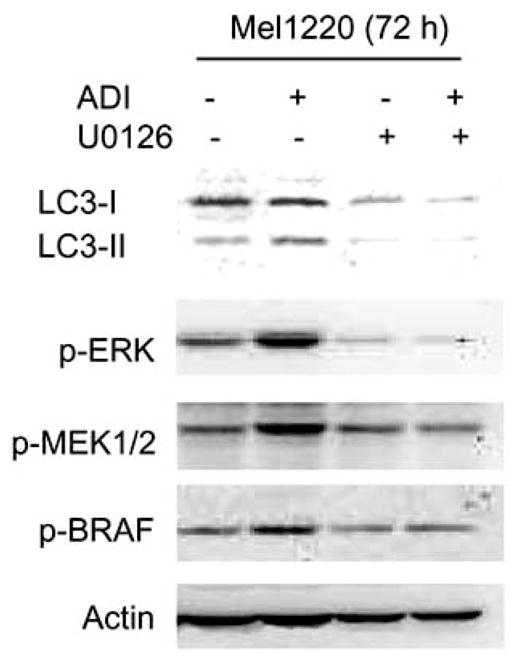

Arginine Deprivation on RAF/MEK/ERK1/2 Signaling

It is known that approximately 60% of melanoma tumors possess BRAF mutation (V600E). Activation of BRAF has been shown to be one of the major growth signaling for melanoma. In fact, BRAF inhibitors have been developed to treat melanoma [32, 33] with variable success depending on the specificity of the compound. We have found that upon treatment with ADI-PEG20, activated MEK and ERK as detected by the phosphorylated form increased while no significant changes occurred in BRAF (Fig. 2) [34]. Interestingly, the addition of MEK inhibitor (U0126) increased both growth inhibitory effect and apoptosis when used in combination with ADI-PEG20 treatment (Fig. 3). Thus, it appears that activation of MEK and ERK may be an attempt for the cells to survive upon arginine deprivation. Therefore, by inhibiting MEK/ERK, the cells can eventually undergo apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Immunoblot of p-ERK1/2, p-MEK and p-BRAF as well as LC3I-II, a marker for autophagy. The appearance of LC3-II or an increase of LC3-I to II represents autophagic process. Cells were treated with ADI-PEG20 (0.06 ug/ml) alone, U0126 (5 uM) alone or both for 72 h. Note: Treatment with ADI-PEG20 increased MEK and ERK phosphorylation while no changes occurred in BRAF. The addition of MEK inhibitor decreased p-MEK and p-ERK as well as decreased autophagy as detected by the disappearance of LC3-II band.

Fig. 3.

A. Growth inhibitory effect with ADI-PEG20 alone (15%), U0126 alone (25%), and in combination (80%) in a melanoma cell line, Mel1220. B. Apoptosis assay by flow cytometry which detects caspase activity and cell death after treatment with ADI-PEG20 (0.05 ug/ml) and U0126 (5 uM). Note: Treatment with ADI-PEG20 alone or U0126 alone produced only 3–6% of cells which were positive for caspase activity and less than 10% cell death (data not shown), while combination treatment produced 26% of cells which are positive for caspase activity and 30% cell death.

Arginine Deprivation Leads to Autophagy in ASS(−) Cells

It is known that nutritional deprivation can lead to autophagy, a lysosomal degradation pathway in which proteins or organelles are sequestrated into autophagosomes which then fuse with lysosomes and degraded [35, 36]. This process can be rapidly activated as an adaptive catabolic process in response to different forms of metabolic stress such as nutritional deprivation, hypoxia or growth factor withdrawal [37–39]. The signaling mechanisms of autophagy are complex and involve multiple pathways, depending upon the cellular context and type of inducers [40–45]. Two evolutionally conserved nutrient pathways play a role in autophagy regulation: (i) Inhibition of mTOR activity which turns off the energy consuming translational process during autophagy and (ii) activation of the eukaryotic kinase initiation factor 2α (GCN2) which represses general translation but upregulates transcriptional activator ATF4 which is required to transcribe stress related genes [46, 47]. Downstream of the TOR kinase, there are 17 genes which are involved in the autophagic process in yeast, termed ATG genes. The ATG gene is involved in the generation and maturation of autophagosome [48]. It is generally accepted that Vps34 (PI3 kinase class III) and Beclin 1 (ATG6) are involved in the vesicle nucleation process [36, 49]. On the other hand, autophagy can also lead to cell death (program type II or non-caspase-dependent cell death) which is characterized by degradation of organelles but preserved cytoskeletal process [47, 50]. Autophagic cell death is known to occur during developmental process [51, 52] and recently in cancer chemotherapy and hormonal therapy [53, 54]. We have found that, upon arginine deprivation, ASS(−) melanoma cells undergo autophagy (Fig. 4A), most likely as part of the adaptive mechanism to avoid cell death. These findings also have been shown by Kim et al. in prostate cancer cell lines which do not express ASS [55, 56]. In fact, our preliminary data also suggest that knock down of Beclin 1 increased cell death resulting from ADI-PEG20 treatment by 20–30% (Fig. 5). In addition, augmentation of autophagy using mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 did not result in increased cell death. Treatment with CCI-779 at 0.05 ug/ml resulted in 4% cell death while ADI-PEG20 (0.1 ug/ml) yielded 9–10% cell death and in combination only 6–7% cell death. It appears that mTOR inhibitor may have protective effect. Thus, these data do not support the notion that increased autophagy results in cell death. Overall, ADI-PEG20 or arginine deprivation treatment induces autophagy in ASS(−) melanoma cell lines; most likely this process represents a mechanism for survival.

Fig. 4.

A. Autophagy as detected by increased LC3-II by western blot and immunofluorescence in Mel-1220 after treatment with ADI-PEG20 for 72 h, and 5 days at 0.06 ug/ml. B. Apoptosis as detected by increased caspase activity and cell death after 6 days of treatment at 0.1 ug/ml of ADI-PEG20 in Mel1220.

Fig. 5.

Increased cell death after silencing Beclin 1 mRNA. The percentage of cell death increased by 20% upon treatment with 0.1 ug/ml of ADI PEG20 for 3 days.

How Arginine Deprivation Induces Cell Death in ASS(−) Melanoma Cells?

Two major forms of cell death, apoptosis and necrosis, have been studied in detail. The majority of traditional chemotherapeutic agents induce cell death via apoptosis which can be caspase-dependent or independent. Recently, autophagic cell death has also been described in tumor cells treated with certain chemotherapeutic agents such as temozolomide [53]. Whether arginine deprivation results in autophagic cell death is not entirely clear. However, arginine deprivation has been shown to induce apoptosis by Gong et al. in human lymphoblastic cell lines [57]. Szlosarek et al. also have shown that ASS(−) mesothelioma cells undergo apoptosis upon arginine deprivation via Bax activation [58, 59]. We have shown that arginine deprivation induces apoptosis in ASS(−) melanoma cell lines [15, 16]. The pathway to apoptosis is not yet clear. Our data indicate that treatment with ADI-PEG20 (0.1 ug/ml) for 6 days results in apoptosis in ASS(−) melanoma cell lines (Fig. 4B). Please note that at this dosage, there is no arginine left in the media in 24 h [15]. The exposure time that lead to apoptosis (ranging from 3–6 days) as well as the extent of apoptosis are different among melanoma cell lines and may be related to the antiapoptotic machinery in the cells. Mel1220 which lacks ASS but has high Bcl-2 undergoes autophagy while apoptosis does not occur until day 5–6 (Fig. 4A & B). Our results also indicate increased caspase activity upon ADI-PEG20 treatment which suggests that cell death is caspase-dependent (Fig. 4B). The addition of caspase 3 inhibitor can block only 80–85% of cell death which implies that caspase-independent cell death may also take place in a small portion of the cell population (data not shown). In contrast, Kim et al. have shown that arginine deprivation-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cell line is caspase-independent [55, 56]. Thus, apoptosis most likely occurs via both caspase-dependent and independent pathway depending on the cell type. Overall, from our data and those reported in the literature, arginine deprivation results in cell death via apoptosis. The question remains whether autophagy can also lead to apoptosis or it is a mechanism solely for survival or both is not yet clear. Our preliminary data and others which showed that silencing Beclin 1 increases cell death support the notion that autophagy plays a major role in survival. Another indirect evidence from our data is that MEK inhibitor U0126 inhibits autophagy and increases cell death (Figs. 2, 3A & B). MEK and ERK have been shown to be involved in autophagy via noncanonical pathway [60, 61]. Recently, Wang et al. [60] have shown that basal MEK/ERK activation prevents the disassembly of mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes. However, activation of MEK/ERK by AMPK upon amino acid deprivation stimulates the disassembly of mTORC1 complex, which leads to autophagy. Furthermore, siRNA of MEK and ERK has been shown to inhibit the autophagy. On the other hand, Pattingre et al. have shown that amino acids interfere with ERK1/2-dependent autophagy, via phosphorylation of GAIP [61]. GAIP is a protein belonging to RGS family, which can stimulate autophagy by increasing the GTPase activity of the G protein and control the formation of autophagic vacuoles. Overall, from our data as well as those available in the literature, we propose that treatment with ADI-PEG20 in ASS(−) melanoma cells results in activation of AMPK, which leads to mTOR inhibition, MEK/ERK activation, and autophagy as a survival mechanism (Fig. 6). On the other hand, arginine deprivation also primes the cells to undergo apoptosis as evidenced by Bax activation [59] and increased DR4/5 expression [62]. When autophagy can no longer provide arginine, the cell will undergo apoptosis (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Growth signaling pathway affected by arginine deprivation in ASS(−) cells which leads to autophagy.

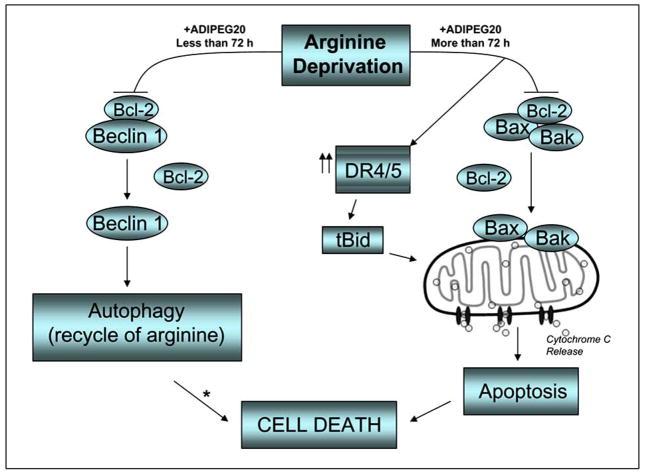

Fig. 7.

Possible mechanism of autophagy and apoptosis upon ADI-PEG20 treatment. Treatment with ADI-PEG20 which depletes arginine in the media will first lead to autophagy as a survival mechanism. With longer duration of exposure and higher dose, apoptosis does occur via Bax/Bak activation. * possible link between autophagy and apoptosis (caspase-independent cell death).

How ASS(−) Cells Evade Apoptotic Cell Death Induced by Arginine Deprivation?

There are two main mechanisms by which cells do not respond to arginine deprivation in vivo. The first mechanism involves tumor cells which possess high ability to undergo autophagy but are apoptosis- resistant. The second mechanism involves tumor cells which can turn on ASS mRNA once they are in arginine-free media. In the second scenario, we have found tumor cells obtained from patients upon relapse re-express both ASS mRNA and ASS protein [24]. In the in vitro model we have also found certain cell lines in which ASS can be induced rather rapidly such as A2058 while in other cell lines such as A375 and Mel1220, ASS mRNA cannot be induced [16]. We have recently shown that HIF-1a and c-Myc are important transcriptional factors in ASS regulation [63]. With regard to the first scenario, we have found that cell lines which overexpress Bcl-2 can undergo autophagy but are resistant to apoptosis unless there is absolutely no arginine in the media. Total lack of arginine is often difficult to achieve in vivo due to supply of arginine from endothelial cells or other normal cells by cell to cell communication. Thus, to overcome this form of resistance, a second drug must be added to push the cells to apoptosis either through the extrinsic or intrinsic pathway. In this regard, we have found that combination of ADI-PEG20 with cisplatin can increase apoptosis in melanoma cell lines (Fig. 8A). The enhancement effect may also be partly due to increase in DNA damage (Fig. 8B) [64]. Other agents such as TRAIL or Bcl-2 antagonist should also be taken into consideration.

Fig. 8.

A. Apoptosis as detected by increased caspase activity and cell death by PI staining in A375 cells. ADI-PEG20 alone at 0.05 ug/ml showed 10% cell death (data not shown), cisplatin alone showed 20% of cells positive for caspase activity and 30% cell death as indicated by PI staining while for the two drug combination the caspase activity increased to 75% and 90% cell death. B. Immunofluorescence of gamma-H2AX (bright dots) which depicts DNA damage. Cisplatin alone showed some increase in gamma-H2AX while the two drug combination showed more cells positive for gamma-H2AX.

CONCLUDING REMARK

The majority of melanomas do not express ASS and hence cannot synthesize arginine from citrulline. Arginine deprivation by the arginine-degrading enzyme arginine deiminase leads to apoptotic cell death while sparing ASS(+) normal cells. We have found that arginine deprivation in these ASS(−) tumor cells leads to decreased ATP and activation of AMPK and eventually inhibition of mTOR. We have also found activation of MEK/ERK with minimal changes in BRAF. Inhibition of mTOR leads to autophagy, a mechanism which enables cells to recycle intracellular arginine. The capability of melanoma cells to undergo autophagy and adapt to levels of arginine is different among melanoma cell lines and may depend on the anti-apoptotic as well as autophagic machinery. However, caspase-dependent and independent apoptosis eventually occur in all ASS(−) melanoma cell lines treated with ADI-PEG20.

From our data as well as data from other laboratories, it appears that autophagy is a mechanism for surviving rather than cell death upon arginine deprivation. Combination of agent(s) which can inhibit autophagy or overcome antiapoptotic machinery can be used with arginine deprivation to potentially increase antitumor activity in melanoma.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by NIH R0O1 CA109578-01 to L. Feun and VA Research fund to N. Savaraj. We wish to thank Polaris Inc. for providing ADI-PEG20.

References

- 1.Copperman R, Morton HE. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966;123:790–795. doi: 10.3181/00379727-123-31605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barile MF, Leventhal BG. Nature. 1968;219:750–752. doi: 10.1038/219751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimura K, Fukuda S, Wada Y, Taniai M, Suzuki M, Kimura T, Ohno T, Yamamoto K, Azuma I. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2510–2515. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2510-2515.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugimura K, Kimura T, Arakawa H, Ohno T, Wada Y, Kimura Y, Saheki T, Azuma I. Leuk Res. 1990;14:931–934. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(90)90184-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugimura K, Ohno T, Fukuda S, Wada Y, Kimura T, Azuma I. Cancer Res. 1990;50:345–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyazaki K, Takaku H, Umeda M, Fujita T, Huang WD, Kimura T, Yamashita J, Horio T. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4522–4527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takaku H, Takase M, Abe S, Hayashi H, Miyazaki K. Int J Cancer. 1992;51:244–249. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takaku H, Matsumoto M, Misawa S, Miyazaki K. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86:840–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb03094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Husson A, Brasse-Lagnel C, Fairand A, Renouf S, Lavoinne A. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:1887–1899. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lind DS. J Nutr. 2004;134:2837S–2841S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2837S. discussion 2853S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris SM., Jr Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:508S–512S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.508S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheatley DN. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.wheatley DN, Campbell E, Lai PBS, Cheng PNM. Gene Ther Mol Biol. 2005;9:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheatley DN, Campbell E. Pathol Oncol Res. 2002;8:18–25. doi: 10.1007/BF03033696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savaraj N, Wu C, Kuo M, You M, Wangpaichitr M, Robles C, Spector S, Feun L. Drug Target Insights. 2007;2:119–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feun L, Wu C, Kuo M, Wangpaichitr M, Spector S, Savaraj N. Curr Pham Des. 2008;14:1049–1057. doi: 10.2174/138161208784246199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ensor CM, Holtsberg FW, Bomalaski JS, Clark MA. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5443–5450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheatley DN, Philip R, Campbell E. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;244:177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam T, Wong G, Chong H, Cheng P, Choi S, Chow T, Kwok S, Poon R, Wheatley D, Lo W. Cancer Lett. 2009;277:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng PN, Lam TL, Lam WM, Tsui SM, Cheng AW, Lo WH, Leung YC. Cancer Res. 2007;67:309–317. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillon BJ, Holtsberg FW, Ensor CM, Bomalaski JS, Clark MA. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:BR248–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izzo F, Montella M, Orlando AP, Nasti G, Beneduce G, Castello G, Cremona F, Ensor CM, Holtzberg FW, Bomalaski JS, Clark MA, Curley SA, Orlando R, Scordino F, Korba BE. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izzo F, Marra P, Beneduce G, Castello G, Vallone P, De Rosa V, Cremona F, Ensor CM, Holtsberg FW, Bomalaski JS, Clark MA, Ng C, Curley SA. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1815–1822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feun L, Savaraj N. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:815–822. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.7.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curley SA, Bomalaski JS, Ensor CM, Holtsberg FW, Clark MA. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1214–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ascierto PA, Scala S, Castello G, Daponte A, Simeone E, Ottaiano A, Beneduce G, De Rosa V, Izzo F, Melucci MT, Ensor CM, Prestayko AW, Holtsberg FW, Bomalaski JS, Clark MA, Savaraj N, Feun LG, Logan TF. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7660–7668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proud CG. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tokunaga C, Yoshino K, Yonezawa K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:443–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoyer-Hansen M, Jaattela M. Autophagy. 2007;3:381–383. doi: 10.4161/auto.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurley RL, Anderson KA, Franzone JM, Kemp BE, Means AR, Witters LA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29060–29066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smoley SA, Brockman SR, Paternoster SF, Meyer RG, Dewald GW. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;148:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(03)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fecher LA, Amaravadi RK, Flaherty KT. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:183–189. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282f5271c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savaraj N, Wu C, You M, Wangpaichitr M, Feun L. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2009 Abstract nr 380. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao Y, Klionsky DJ. Cell Res. 2007;17:839–849. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin S, White E. Autophagy. 2007;3:28–31. doi: 10.4161/auto.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pattingre S, Espert L, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Codogno P. Biochimie. 2008;90:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H, Bosch-Marce M, Shimoda LA, Tan YS, Baek JH, Wesley JB, Gonzalez FJ, Semenza GL. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10892–10903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800102200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Wang Y, Singh R, Massey AC, Kane SS, Kaushik S, Grant T, Xiang Y, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4766–4777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706666200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu S, Kanaseki T, Mizushima N, Mizuta T, Arakawa-Kobayashi S, Thompson CB, Tsujimoto Y. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1221–1228. doi: 10.1038/ncb1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Codogno P, Meijer AJ. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12 (Suppl 2):1509–1518. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kondo Y, Kanzawa T, Sawaya R, Kondo S. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amaravadi RK, Yu D, Lum JJ, Bui T, Christophorou MA, Evan GI, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Thompson CB. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:326–336. doi: 10.1172/JCI28833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lum JJ, Bauer DE, Kong M, Harris MH, Li C, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. Cell. 2005;120:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kilberg MS, Pan YX, Chen H, Leung-Pineda V. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:59–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine B, Yuan J. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2679–2688. doi: 10.1172/JCI26390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102–1109. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Obara K, Noda T, Niimi K, Ohsumi Y. Genes Cells. 2008;13:537–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scarlatti F, Granata R, Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bursch W, Hochegger K, Torok L, Marian B, Ellinger A, Hermann RS. J Cell Sci. 2000;113 (Pt 7):1189–1198. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.7.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mills KR, Reginato M, Debnath J, Queenan B, Brugge JS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3438–3443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400443101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanzawa T, Germano IM, Komata T, Ito H, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:448–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bilir A, Altinoz MA, Erkan M, Ozmen V, Aydiner A. Pathobiology. 2001;69:120–126. doi: 10.1159/000048766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim RH, Bold RJ, Kung HJ. Autophagy. 2009;5:567–568. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.4.8252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim RH, Coates JM, Bowles TL, McNerney GP, Sutcliffe J, Jung JU, Gandour-Edwards R, Chuang FY, Bold RJ, Kung HJ. Cancer Res. 2009;69:700–708. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gong H, Zolzer F, von Recklinghausen G, Havers W, Schweigerer L. Leukemia. 2000;14:826–829. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Szlosarek P, Klabatsa A, Pallaska A, Sheaf fM, Balkwell F, Fennell D. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2006 Abstract nr 2206. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szlosarek PW, Klabatsa A, Pallaska A, Sheaff M, Smith P, Crook T, Grimshaw MJ, Steele JP, Rudd RM, Balkwill FR, Fennell DA. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7126–7131. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J, Whiteman MW, Lian H, Wang G, Singh A, Huang D, Denmark T. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21412–21424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pattingre S, Bauvy C, Codogno P. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16667–16674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210998200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.You M, Savaraj N, Wangpaichitr M, Wu C, Kuo MT, Varona-Santos J, Nguyen DM, Feun L. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.066. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsai WB, Aiba I, Lee SY, Feun L, Savaraj N, Kuo MT. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3223–3233. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feun L, Wu C, Lee S, Kuo M, Wangpaichitr M, Robles C, Savaraj N. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2007:4042. [Google Scholar]