Abstract

Corneal transplantation has been performed successfully for over 100 years. Normally, HLA typing and systemic immunosuppressive drugs are not utilized, yet 90% of corneal allografts survive. In rodents, corneal allografts representing maximal histoincompatibility enjoy >50% survival even without immunosuppressive drugs. By contrast, other categories of transplants are invariably rejected in such donor/host combinations. The acceptance of corneal allografts compared to other categories of allografts is called immune privilege. The cornea expresses factors that contribute to immune privilege by preventing the induction and expression of immune responses to histocompatibility antigens on the corneal allograft. Among these are soluble and cell membrane molecules that block immune effector elements and also apoptosis of T lymphocytes. However, some conditions rob the corneal allograft of its immune privilege and promote rejection, which remains the leading cause of corneal allograft failure. Recent studies have examined new strategies for restoring immune privilege to such high-risk hosts.

Keywords: corneal allografts, immune privilege, keratoplasty, transplantation

HISTORY OF IMMUNE PRIVILEGE AND CORNEAL TRANSPLANTATION

Corneal allografts remain the most common and, arguably, the most successful form of solid organ transplantation. In the United States alone, over 41,000 corneal transplants were performed in 2007.1 The unique properties of corneal transplants were recognized over 100 years ago when Zirm reported the first successful keratoplasty in a human subject, some decades before corticosteroids and anti-rejection agents became available.2 The immunological significance of this finding was not fully appreciated until almost 50 years later when Billingham and Medawar noted the remarkably enhanced survival of orthotopic corneal allografts in rabbits and the prolonged survival of heterotopic skin allografts placed into the anterior chamber (AC) of the rabbit eye.3,4 Medawar recognized the significance of these findings and coined the term immune privilege to describe the corneal allograft’s apparent exemption from the laws of transplantation.4

Immune privilege is a widely recognized, but often misunderstood phenomenon. One major misconception regarding immune privilege is the assumption that immune responses in immune-privileged sites such as the AC are universally excluded. Although many tissue and tumor allografts enjoy prolonged and sometimes permanent survival in the AC, there are exceptions.5–8 For example, highly immunogenic syngeneic and allogeneic tumor grafts can circumvent immune privilege and undergo immune rejection in the AC.7,9–11 While corneal allografts enjoy a survival rate that exceeds all other categories of allografts when performed under the same conditions, corneal allograft rejection can occur.12–19 Nonetheless, corneal allografts enjoy remarkable immune privilege when one considers that HLA matching is not routinely performed in low-risk patients and topical corticosteroids are the only immunosuppressive agent used.12,17,20,21 The development of the rat and mouse models of penetrating keratoplasty has allowed investigators to precisely define the immune privilege of corneal allografts.22,23 Studies in these models have shown that the incidence of rejection of corneal allografts representing the maximum disparity between donor and recipient (i.e., MHC plus multiple minor histocompatibility loci mismatches) is approximately 50%.15–17 The availability of inbred, congenic mouse and rat strains has facilitated studies that have further defined the boundaries of immune privilege and demonstrated that immune privilege is even more impressive for corneal allografts in which the donor and host are mismatched only at MHC class I loci. Under these conditions, corneal allograft survival is 65 and 70% in the rat and mouse, respectively.17 In contrast, similarly mismatched skin and heart allografts are routinely rejected in 100% of the hosts.

Animal studies have shown that immune privilege is abolished and corneal allografts undergo immune rejection in virtually any condition in which inflammation, neovascularization, or trauma is present in the cornea.17,21,24,25 A similar outcome occurs in keratoplasty patients who have ongoing ocular inflammation, preexisting corneal neovascularization, or a history of previous corneal graft rejection. Graft rejection in these patients climbs to >60%.26 Although the survival of other categories of transplants, such as liver, kidney, and heart, has improved in the past 15 years, the long-term acceptance of corneal allografts has remained unchanged.27 However, it should be noted that improved systemic immunosuppressive drugs have undoubtedly contributed to the enhanced survival of heart, kidney, and liver transplants. By contrast, topical corticosteroids remain the only immunosuppressive agents routinely used in corneal allograft recipients. Kidney, heart, and liver transplants are performed as life-saving procedures, while corneal transplantation is not as urgent and, thus, the aggressive use of systemic immunosuppressive drugs is not normally employed in keratoplasty patients. The extraordinarily high acceptance of corneal allografts in rodents in the absence of immunosuppressive drugs, either topical or systemic, and the 90% acceptance rate for corneal allografts in low-risk keratoconus patients are compelling evidence of the immune privilege of corneal allografts.17,20,27

MECHANISMS OF IMMUNE PRIVILEGE

Role of the Avascular Graft Bed in Blocking the Afferent Arm of the Immune Response

Immune privilege of corneal allografts is sustained by one or more of the following: (1) blocking the induction of immune responses; (2) deviating immune responses down a tolerogenic pathway; or (3) blocking the expression of effector T cells and complement activation (Table 1). Perhaps the most widely accepted and oldest explanation for corneal allograft survival relates to the remarkable absence of blood and lymph vessels in the noninflamed cornea and juxtaposed graft bed. Trauma or infections of the ocular surface can elicit corneal neovascularization, which has long been recognized as a major risk factor for corneal allograft rejection. Although it was originally believed that the presence of blood vessels promoted the induction and expression of alloimmunity, it has recently been shown that it is the presence of lymph vessels and not blood vessels that robs the corneal allograft of its immune privilege.28 Highly vascularized graft beds can be produced by inserting sutures into the corneas of mice several days prior to the application of orthotopic corneal allografts. Using this approach, Dietrich and co-workers reported that administration of either a small molecule antagonist of α5β1 integrin or anti-VEGFR3 antibody, preferentially inhibited lymphangiogenesis, but not hemangiogenesis and produced a significant enhancement of graft acceptance in hosts whose graft beds were pretreated with sutures.28 VEGF-C or VEGF-D binds to VEGF receptor 3 (VEGFR-3) and induces blood and lymph vessel formation in the cornea.29,30 Administration of soluble VEGFR-3 suppresses both lymphangiogenesis and hemangiogenesis.31 It has recently been reported that corneal epithelial and stromal cells secrete a soluble form of VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR-2), which blocks VEGF-C and inhibits lymphangiogenesis in the cornea, but does not affect hemangiogenesis.32 Thus, the absence of lymph vessels in the normal cornea is maintained, at least in part, by the constitutive local production of VEGFR-2 by the corneal epithelium and stroma. However, this homeostasis can be overwhelmed by stimuli such as suturing or corneal infections, which stimulate the generation of lymph vessels. The importance of VEGFR-2 was confirmed in studies in which the administration of exogenous soluble VEGFR-2 inhibited lymph vessel formation and doubled corneal allograft survival in rats in which corneal sutures were used to induce vascularization of the cornea prior to transplantation.32

TABLE 1.

Factors that contribute to immune privilege of corneal allografts

| Factor | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| VEGFR-2 | Blocks lymph vessel formation in the cornea, which prevents APC from emigrating to regional lymph nodes and inducing alloimmune responses. | [32] |

| T regs | Corneal allografts induce T regs, which inhibit induction and function of alloimmune T lymphocytes. | [37,61] |

| CRP | Disables complement components and protects corneal cells from complement-mediated cytolysis by complement-fixing alloantibodies. | [50,52,54,55] |

| FasL | Induces apoptosis of neutrophils and T cells at graft–host interface. | [45,46] |

| PD-L1 | Inhibits T-lymphocyte proliferation and induces apoptosis of T cells at graft–host interface. | [47,48] |

| MIF | Inhibits NK cells and prevents cytolysis of MHC class I-negative corneal endothelial cells. | [58,59] |

Note. VEGFR-2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2; T regs, T regulatory cells; CRP, complement regulatory proteins; FasL, Fas ligand (CD95L); PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; MIF, macrophage migration inhibitory factor.

The long-held hypothesis that the presence of blood vessels in a corneal graft bed raises the risk for rejection is still valid. However, findings from the mouse model of penetrating keratoplasty have shed new light on this observation and have shown that the stimuli that induce blood vessel ingrowth (e.g., VEGF-C) also stimulate lymph vessel growth and the infiltration of resident antigen-presenting cells, both of which conspire to promote immune rejection. Recent studies have also shown that it is feasible to selectively inhibit lymph vessel development in the graft bed and restore the immune privilege of corneal allografts.

Role of Immune Deviation and T Regulatory Cells in Corneal Allograft Survival

Antigens introduced into the anterior chamber (AC) induce a unique spectrum of systemic immune responses that are characterized by the antigen-specific suppression of delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses and the preferential production of non-complement-fixing antibody isotypes (i.e., IgG1 in the mouse) and the exclusion of complement-fixing antibodies. This form of immune deviation was described over 30 years ago and is termed anterior chamber-associated immune deviation (ACAID).33–35 Orthotopic corneal allografts lie over the AC and are in direct contact with the aqueous humor, which contains numerous anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive molecules.36 It has been proposed that during and after surgery, corneal endothelial cells are sloughed from corneal allografts and enter the AC, where they induce ACAID. This, in turn, suppresses alloimmune responses and promotes corneal allograft survival. It is noteworthy that mice bearing long-term clear corneal allografts display antigen-specific suppression of DTH responses that are similar to those observed in ACAID.34,37,38 Moreover, manipulations that abrogate ACAID also produce a steep increase in the incidence of corneal allograft rejection.34,39,40 Induction of ACAID by AC injection of donor strain cells prior to penetrating keratoplasty significantly enhances corneal allograft survival in both the rat and the mouse.41–43 Thus, the corneal allograft and the AC of the eye conspire to actively downregulate alloimmune responses in a manner that greatly reduces the risk for immune rejection.

Blockade of Immune Effector Elements

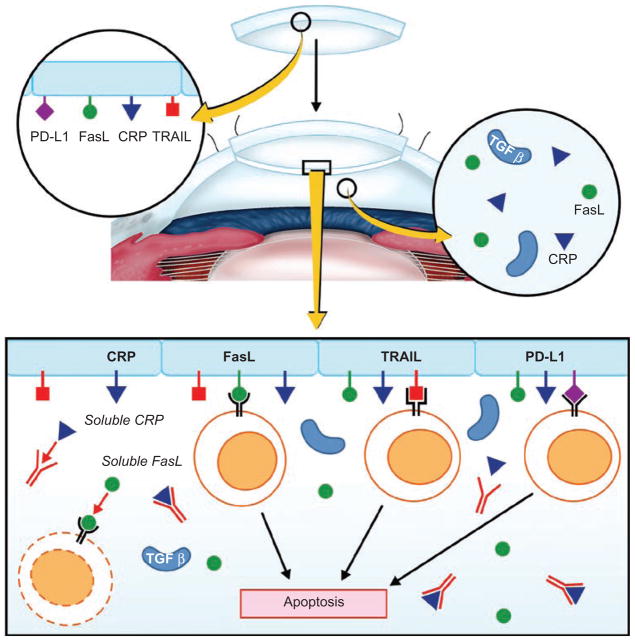

The cornea expresses an array of cell membrane-bound molecules that neutralize immune effector elements. FasL (CD95L) is expressed on the cell membranes on many cells within the eye, including the corneal endothelium, and induces apoptosis of neutrophils and lymphocytes that encounter the cornea during inflammation.44 Corneal allografts prepared from donor mice with defective FasL (gld/gld) experience a twofold increase in the incidence of rejection.45,46 Like FasL, programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) is expressed on the cornea and when it engages its receptor (PD-1) on lymphocytes, it inhibits T-lymphocyte proliferation, induces T-lymphocyte apoptosis, and prevents T-lymphocyte production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ). Corneal allografts from PD-L1−/− donors have a steep increase in the incidence and tempo of rejection compared to grafts that express functional PD-L1.47,48 Likewise, blocking PD-L1/PD-1 interactions by in vivo administration of anti-PD-L1 antibody results in a similar increase in corneal allograft rejection.47,48 Thus, corneal allografts have at least two cell membrane-bound molecules that not only repel T-lymphocyte-mediated attack, but also purge inflammatory cells at the graft/host interface (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Cell membrane-bound molecules expressed on the corneal endothelium block the expression of effector T cells and complement activation. Complement regulatory proteins (CRPs) are expressed on the cell membranes of corneal endothelial cells and are also present in soluble forms in the aqueous humor. CRPs disable the complement cascade and protect the corneal allograft from complement-mediated cytolysis. Fas ligand (FasL) is expressed on the corneal endothelium and in soluble forms in the aqueous humor and induces apoptosis of activated T cells and neutrophils. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is expressed on the corneal endothelium and induces apoptosis of activated T cells expressing its receptor (TRAIL-R2). The role of TRAIL in the immune privilege of corneal allografts is unknown at the present time. Programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) is expressed on the corneal endothelium, inhibits T-cell proliferation, and, in some circumstances, induces apoptosis of T cells expressing its receptor, PD-1.

Although corneal allografts can induce the generation of alloantibodies, the role of antibody in corneal allograft rejection is unresolved.49 Under certain conditions, passive transfer of alloantibody can result in the rejection of corneal allografts in mice.50,51 However, the capacity of complement-fixing antibodies to produce corneal allograft rejection is restrained by the buffering effects of cell membrane-bound complement regulatory proteins (CRP) that are expressed on corneal epithelial cells and the soluble CRP that are present in the aqueous humor.52–54 Murine corneal endothelial cells do not express CRP and are highly susceptible to complement-mediated cytolysis in vitro.50,55 However, aqueous humor contains soluble CRP that protect corneal endothelial cells from complement-mediated cytolysis in vitro and presumably in vivo.50,55 The combination of cell membrane-bound CRP and soluble CRP in the aqueous humor that bathes the corneal endothelium acts to disable complement-mediated effector mechanisms and greatly reduce the likelihood of graft rejection.

One of the unique properties of the corneal endothelium is the absence or extraordinarily low expression of MHC class Ia molecules. Natural killer (NK) cells are members of the innate immune system that are believed to be important in the immune surveillance of tumors. Many neoplasms downregulate their expression of MHC class I molecules as a means of escaping cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)-mediated immune surveillance. To counter this evasive mechanism, cells of the innate immune system, namely natural killer (NK) cells, are programmed to kill any cells that fail to express MHC class I molecules—a phenomenon called the “missing self” hypothesis.56 The missing self phenomenon puts the corneal endothelium at risk for NK cell-mediated attack. However, to date, there is no compelling direct evidence implicating NK cells in the rejection of corneal allografts. The aqueous humor that bathes the corneal endothelium contains at least two molecules that inhibit NK cell-mediated cytolysis. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) produces an immediate inhibition of NK cell-mediated cytolysis,57–59 while transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) produces a similar degree of inhibition, but is delayed in exerting its effect for 18–20 h.60 Importantly, both of these molecules are present in the aqueous humor at concentrations that are known to produce profound inhibition of NK cell-mediated cytolysis.

Thus, the cornea and the underlying aqueous humor have the capacity to not only block, but also eliminate immune effector elements from both the adaptive and innate immune systems. This “sword and shield” strategy provides yet one more layer of immune privilege to the corneal allograft.

STRATEGIES FOR RESTORING OR SUPPLEMENTING IMMUNE PRIVILEGE

From earliest investigation in the 1940s, our understanding of the components of immune privilege of the cornea and anterior chamber has incrementally increased. Coupled with a wider range of available techniques to modulate the immune response of ocular tissues, this has more recently facilitated interventions to restore or augment immune privilege. First, it must be stated that while it is easy to abrogate immune privilege by such interventions as experimental induction of corneal vascularization or transplantation of an identical donor strain skin allograft prior to corneal transplantation, it is much more difficult to restore a meaningful degree of immune privilege, for example, leading to allograft acceptance in a setting in which controls are uniformly rejected. That said, corneal transplantation is the setting par excellence in ophthalmology in which interventions to augment immune privilege would lead to new possibilities in surgical management of corneal opacity to which there is at present no effective alternative.

Immunomodulatory Gene Transfer

As a number of mechanisms of corneal immune privilege are mediated by cell surface proteins or soluble factors in the aqueous humor, it may be possible to supplement immune privilege by increasing their expression. Because expression of an immunomodulatory molecule in the cornea or anterior chamber would be required for longer duration than short term in order to delay transplant rejection to a clinically meaningful extent, vector-mediated gene transfer approaches have been investigated in most studies to enable sustained expression. The most effective approaches have used replication-deficient adenoviral or lentiviral vectors rather than nonviral vectors on account of longer-duration expression and transduction of a higher proportion of endothelial cells. Protection of the corneal endothelium from injury by alloreactive effector cells and molecules is one important target because (1) this cell layer is critical for maintenance of transparency in the donor cornea, and (2) once damaged, the cells of this monolayer cannot be replaced by mitosis in survival of neighboring cells. Following transfer to donor cornea prior to transplantation, therapeutic transgenes encoding the following proteins have been shown to prolong corneal graft survival: soluble TNF receptor,62 soluble CTLA4.Ig,63 interleukin-10,64 the p40 subunit of interleukin-12,65,66 indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase,67 and nerve growth factor.68 Transplant models in which these candidate genes have been investigated are mouse, rat, rabbit, and sheep.

Anti-angiogenesis Interventions

Direct inhibition of hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis is an approach to restoration of immune privilege that has clear possible benefits in corneal transplantation. Inhibition of corneal hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis has been reported using inhibitors of VEGF-A69 or VEGFR-3 signaling,70 with associated reduction in APC trafficking and improvement in graft survival. More recent work by Dietrich et al. has shown the greater importance of lymphangiogenesis than hemangiogenesis in immune privilege, at least in the context of transplantation and the lengthening of allograft survival following selective inhibition of lymphangiogenesis by anti-VEGFR-3 antibodies and anti-alpha 5 integrin small molecules.28

Lymphadenectomy

An entirely different approach to restoring immune privilege in an indirect manner is interference with local lymph node drainage to modulate allograft survival. Antigen from the anterior chamber is known to drain to preauricular and submandibular lymph nodes.71 Experimental lymphadenectomy prolongs corneal graft survival, suggesting that removal of the local nodes in high-rejection risk mice prevents rejection by mechanisms involving immune “ignorance,” since prior allosensitization prevented graft acceptance after node removal.72,73

CONDITIONS THAT ABROGATE IMMUNE PRIVILEGE IN CLINICAL CORNEAL ALLOTRANSPLANTATION

Post-transplant Local Allo-independent Events

A high proportion of the human corneal allografts that undergo rejection are, in fact, not perceived to be at high rejection risk pretransplant. In these graft recipients a post-transplant event leads to subversion of immune privilege. These events are local episodes of alloantigen-independent inflammation, such as a loosened transplant suture, bacterial suture-associated infection, or herpetic infection recurrence. These lead to recruitment of alloreactive cells, angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, and upregulation of MHC molecules on the graft cells, and sequelae, which in combination lead to an acute onset rejection response. On the other hand, in high-rejection-risk transplants it is implied that there is preexisting erosion of one or more facets of immune privilege, as follows.

Vascularization of the Graft Recipient Bed

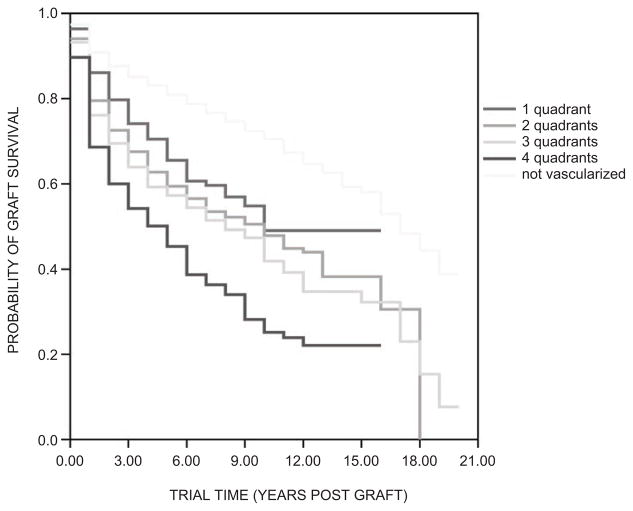

The importance of corneal avascularity in maintaining ocular immune privilege, firmly established for so long by experimental studies summarized above, is indicated by the fact that recipient corneal vascularization is the most statistically significant factor on multivariate analyses predicting risk of transplant failure74 due to rejection. Long-term corneal transplant outcome in the largest prospective patient cohort demonstrates stratification of graft survival according to the number of quadrants of vascularization (Figure 2). Considering that in studies of interventions in high-rejection-risk corneal transplantation, vascularization in more than one recipient corneal quadrant is conventionally taken as the eligibility criterion. It is of note that survival of grafts in corneas with vascularization in one quadrant diverges more widely from that of those with zero than two vascularized quadrants.

FIGURE 2.

Stratification of actuarial corneal transplant survival according to the number of quadrants of recipient cornea vascularized at the time of transplantation. (Adapted with permission from Coster DJ, Williams KA. The impact of corneal allograft rejection on long-term outcome of corneal transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1112–1122.)

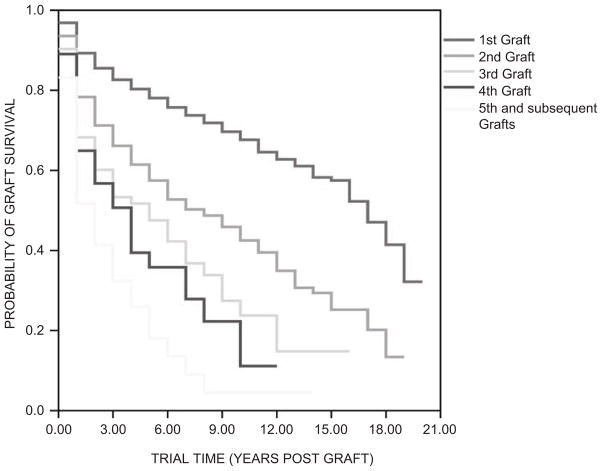

Rejected Previous Transplant

Stratification of corneal transplant survival according to the number of preceding transplants in a recipient eye is clear evidence of the importance of absent prior allosensitization in immune privilege (Figure 3). This decreasing survival of successive corneal transplants indicates that second set and subsequent corneal transplants are at progressively increased risk of rejection in the same way as other transplanted tissues. Whether corneal allograft rejection is accompanied by vascularization or not (Figure 4), there is heightened risk of rejection of a subsequent allograft even though the recipient cornea is avascular. In some patients with vascularized corneal beds in which an earlier transplant has failed due to rejection, the comparative immune privilege of the cornea and anterior chamber can be completely abrogated such that even levels of immunosuppression used as rejection prophylaxis in vascularized organ transplantation fail to prevent rejection of a subsequent corneal transplant.75

FIGURE 3.

Stratification of actuarial corneal transplant survival according to the number of rejected previous ipsilateral transplants. (Adapted with permission from Coster DJ, Williams KA. The impact of corneal allograft rejection on long-term outcome of corneal transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1112–1122.)

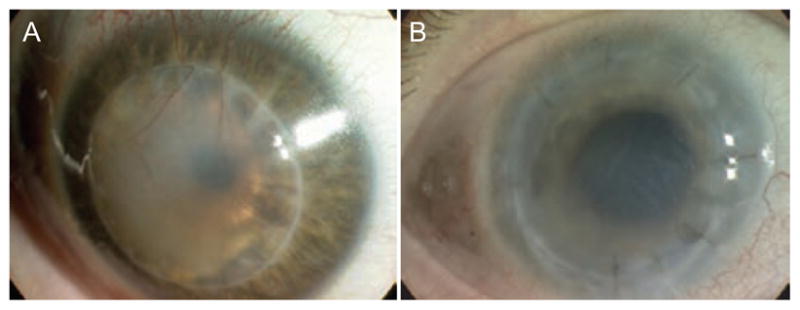

FIGURE 4.

Neovascularization in corneal allograft rejection. Corneal neovascularization dramatically increases the risk of immune rejection. Deep stromal vessels are easily seen in many rejected corneal allografts (A), yet some corneal allografts undergo rejection without evidence of macroscopically detectable vessels (B).

Inflammation at the Time of Transplant

In patients with an indication for transplant in which the cornea is uninflamed, such as keratoconus or a corneal dystrophy, graft survival rates of 90% after 10 years are common, whereas a recipient cornea previously inflamed or inflamed at the time of transplantation is associated with significantly reduced survival times. Inverse correlation of leucocyte counts in the graft bed with actuarial graft survival in patients has been recognized since the first clinicopathological report.76 From finding a high APC count in excised recipient cornea it is inferred that equivalent high counts are present in the peripheral recipient cornea, increasing the probability of indirect allorecognition by these APCs and subsequent rejection. Mindful of this important poor prognostic factor for rejection-free graft survival, corneal transplantation is avoided in actively inflamed eyes and, other clinical circumstances permitting, an attempt is made to obtain the best possible control of corneal inflammation before transplantation.

Atopy

A high proportion of those patients with keratoconus, itself the commonest indication for corneal transplantation, are atopic. Within this subset the severity and spectrum of allergic disorders is variable, some having severe allergic keratoconjunctivitis and others no ocular allergy. Observations in experimental models and in patients indicate higher risk of rejection in this setting, by mechanisms that are not fully understood. Increased risk of rejection following transplantation in keratoconus patients with ocular allergy had been understood to result from the erosion of immune privilege associated with corneal inflammation at or before transplant, independent of any allergy-specific influence. However, a recent report of higher rejection risk in patients with atopic dermatitis, even in the absence of clinically evident conjunctival allergy, points to a role of systemic atopy in erosion of corneal transplant privilege.77 Dissection of the influence of atopy on corneal immune privilege has been undertaken by corneal transplantation in a murine asthma model, demonstrating that airway allergen exposure alone increases allograft rejection risk and for the duration of the systemic allergic response to nonocular allergen.78

Studies on corneal transplantation in allergic conjunctivitis have found accelerated allograft rejection in the setting of perioperative or sustained local conjunctival inflammation and also in the contralateral uninflamed eye.79,80 Presence of an eosinophilic component in the alloreactive effector population in rejected corneas indicates the single facet of the effector response seen only in atopic graft recipients, typical of a Th2 IL-5-driven response. There may be phenotypic or functional alterations in conjunctival APC in allergy, which alter the afferent component of the rejection response, but little is understood about the afferent component of the allogeneic response in this setting and the mechanism by which the immune privilege of cornea is overridden in atopic hosts.

CONCLUSIONS

In recipients in which immune privilege is operative, we may ask of grafts that are not rejected whether the recipient has not been sensitized due to ignorance of the alloantigen, whether the antigen has been recognized but an allogeneic response is not mounted (tolerance), or whether the immune system has seen the antigen and been sensitized but its effector cells cannot see the target antigen due to sequestration of the graft in its avascular bed. It is likely that the relative contributions to immune privilege at each step differ for each recipient and each graft, taking into account donor–recipient transplantation antigen disparity and other factors, notably those known to erode immune privilege. There is no component contributing to immune privilege that cannot be overcome by one of the many redundant cellular pathways and mechanisms known to bring about rejection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Keryn Williams for Figures 2 and 3, prepared kind provision of with data from the Australian Corneal Graft Register. This work was supported by a grant from Research to Prevent Blindness and NIH grant EY007641.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.America EBA. Statistical Report on Eye Banking Activity for 2008. www.restoresightorg/donation/statisticshtm2008.

- 2.Zirm E. Eine erfolgreiche totale Keratoplastik. Albrecht von Graefes Arch Ophthalmol. 1906;64:580–593. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billingham RE, Boswell T. Studies on the problem of corneal homografts. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1953;141(904):392–406. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1953.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medawar PB. Immunity to homologous grafted skin, III: the fate of skin homografts transplanted to the brain, to subcutaneous tissue, and to the anterior chamber of the eye. Br J Exp Pathol. 1948;29:58–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niederkorn JY. Immunoregulation of intraocular tumours. Eye. 1997;11(Pt 2):249–254. doi: 10.1038/eye.1997.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niederkorn JY. Immune escape mechanisms of intraocular tumors. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28(5):329–347. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niederkorn JY, Meunier PC. Spontaneous immune rejection of intraocular tumors in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26(6):877–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niederkorn JY, Wang S. Immunology of intraocular tumors. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13(1):105–110. doi: 10.1080/09273940490518586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dace DS, Chen PW, Alizadeh H, et al. Ocular immune privilege is circumvented by CD4+ T cells, leading to the rejection of intraocular tumors in an IFN-{gamma}-dependent manner. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(2):421–429. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knisely TL, Luckenbach MW, Fischer BJ, et al. Destructive and nondestructive patterns of immune rejection of syngeneic intraocular tumors. J Immunol. 1987;138(12):4515–4523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knisely TL, Niederkorn JY. Emergence of a dominant cytotoxic T lymphocyte antitumor effector from tumor-infiltrating cells in the anterior chamber of the eye. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1990;30(6):323–330. doi: 10.1007/BF01786881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George AJ, Larkin DF. Corneal transplantation: the forgotten graft. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(5):678–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hori J, Joyce NC, Streilein JW. Immune privilege and immunogenicity reside among different layers of the mouse cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(10):3032–3042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niederkorn JY. The immune privilege of corneal allografts. Transplantation. 1999;67(12):1503–1508. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199906270-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niederkorn JY. The immunology of corneal transplantation. Dev Ophthalmol. 1999;30:129–40. doi: 10.1159/000060740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niederkorn JY. Immunology and immunomodulation of corneal transplantation. Intern Rev Immunol. 2002;21(173–196):173–196. doi: 10.1080/08830180212064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niederkorn JY. The immune privilege of corneal grafts. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74(2):167–171. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1102543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams KA, Coster DJ. Rethinking immunological privilege: implications for corneal and limbal stem cell transplantation. Mol Med Today. 1997;3(11):495–501. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(97)01122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams KA, Coster DJ. The immunobiology of corneal transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84(7):806–813. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000285489.91595.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Group CCTSR. The collaborative corneal transplantation studies (CCTS): effectiveness of histocompatibility matching in high-risk corneal transplantation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110(10):1392–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streilein JW. New thoughts on the immunology of corneal transplantation. Eye. 2003;17(8):943–948. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.She SC, Steahly LP, Moticka EJ. A method for performing full-thickness, orthotopic, penetrating keratoplasty in the mouse. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21(11):781–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams KA, Coster DJ. Penetrating corneal transplantation in the inbred rat: a new model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26(1):23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He YG, Niederkorn JY. Depletion of donor-derived Langerhans cells promotes corneal allograft survival. Cornea. 1996;15(1):82–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada J, Yoshida M, Taylor AW, et al. Mice with Th2-biased immune systems accept orthotopic corneal allografts placed in “high risk” eyes. J Immunol. 1999;162(9):5247–5255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams KA, Muehlberg SM, Lewis RF, et al. Long-term outcome in corneal allotransplantation. The Australian Corneal Graft Registry. Transplant Proc. 1997;29(1–2):983. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldock A, Cook SD. Corneal transplantation: how successful are we? Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84(8):813–815. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dietrich T, Bock F, Yuen D, et al. Cutting edge: lymphatic vessels, not blood vessels, primarily mediate immune rejections after transplantation. J Immunol. 2009;184(2):535–539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cursiefen C, Chen L, Borges LP, et al. VEGF-A stimulates lymphangiogenesis and hemangiogenesis in inflammatory neovascularization via macrophage recruitment. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(7):1040–1050. doi: 10.1172/JCI20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stacker SA, Achen MG, Jussila L, et al. Lymphangiogenesis and cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(8):573–583. doi: 10.1038/nrc863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cursiefen C, Chen L, Saint-Geniez M, et al. Nonvascular VEGF receptor 3 expression by corneal epithelium maintains avascularity and vision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(30):11405–11410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albuquerque RJ, Hayashi T, Cho WG, et al. Alternatively spliced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 is an essential endogenous inhibitor of lymphatic vessel growth. Nat Med. 2009;15(9):1023–1030. doi: 10.1038/nm.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niederkorn JY. See no evil, hear no evil, do no evil: the lessons of immune privilege. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(4):354–359. doi: 10.1038/ni1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niederkorn JY. Anterior chamber-associated immune deviation and its impact on corneal allograft survival. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2006;11:360–365. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streilein JW. Ocular immune privilege: therapeutic opportunities from an experiment of nature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(11):879–889. doi: 10.1038/nri1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor AW. Ocular immunosuppressive microenvironment. Chem Immunol. 2007;92:71–85. doi: 10.1159/000099255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonoda Y, Ksander B, Streilein JW. Evidence that active suppression contributes to the success of H-2-incompatible orthotopic corneal allografts in mice. Transplant Proc. 1993;25(1 Pt 2):1374–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonoda Y, Streilein JW. Impaired cell-mediated immunity in mice bearing healthy orthotopic corneal allografts. J Immunol. 1993;150(5):1727–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skelsey ME, Mellon J, Niederkorn JY. Gamma delta T cells are needed for ocular immune privilege and corneal graft survival. J Immunol. 2001;166(7):4327–4333. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonoda KH, Taniguchi M, Stein-Streilein J. Long-term survival of corneal allografts is dependent on intact CD1d-reactive NKT cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(4):2028–2034. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niederkorn JY, Mellon J. Anterior chamber-associated immune deviation promotes corneal allograft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(13):2700–2707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.She SC, Moticka EJ. Ability of intracamerally inoculated B- and T-cell enriched allogeneic lymphocytes to enhance corneal allograft survival. Int Ophthalmol. 1993;17(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00918860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.She SC, Steahly LP, Moticka EJ. Intracameral injection of allogeneic lymphocytes enhances corneal graft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31(10):1950–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffith TS, Brunner T, Fletcher SM, et al. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege. Science. 1995;270(5239):1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stuart PM, Griffith TS, Usui N, et al. CD95 ligand (FasL)-induced apoptosis is necessary for corneal allograft survival. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(3):396–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI119173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamagami S, Kawashima H, Tsuru T, et al. Role of Fas–Fas ligand interactions in the immunorejection of allogeneic mouse corneal transplants. Transplantation. 1997;64(8):1107–1111. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199710270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hori J, Wang M, Miyashita M, et al. B7-H1-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege of corneal allografts. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):5928–5935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen L, Jin Y, Freeman GJ, et al. The function of donor versus recipient programmed death-ligand 1 in corneal allograft survival. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):3672–3679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niederkorn JY. Immune mechanisms of corneal allograft rejection. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32(12):1005–1016. doi: 10.1080/02713680701767884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hegde S, Mellon JK, Hargrave SL, et al. Effect of alloantibodies on corneal allograft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(4):1012–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holan V, Vitova A, Krulova M, et al. Susceptibility of corneal allografts and xenografts to antibody-mediated rejection. Immunol Lett. 2005;100(2):211–213. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bora NS, Gobleman CL, Atkinson JP, et al. Differential expression of the complement regulatory proteins in the human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34(13):3579–3584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goslings WR, Prodeus AP, Streilein JW, et al. A small molecular weight factor in aqueous humor acts on C1q to prevent antibody-dependent complement activation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(6):989–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lass JH, Walter EI, Burris TE, et al. Expression of two molecular forms of the complement decay-accelerating factor in the eye and lacrimal gland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31(6):1136–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hargrave SL, Mayhew E, Hegde S, et al. Are corneal cells susceptible to antibody-mediated killing in corneal allograft rejection? Transpl Immunol. 2003;11(1):79–89. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(02)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ljunggren HG, Karre K. In search of the ‘missing self’: MHC molecules and NK cell recognition. Immunol Today. 1990;11(7):237–244. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90097-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Apte RS, Mayhew E, Niederkorn JY. Local inhibition of natural killer cell activity promotes the progressive growth of intraocular tumors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38(6):1277–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Apte RS, Niederkorn JY. Isolation and characterization of a unique natural killer cell inhibitory factor present in the anterior chamber of the eye. J Immunol. 1996;156(8):2667–2673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Apte RS, Sinha D, Mayhew E, et al. Cutting edge: role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in inhibiting NK cell activity and preserving immune privilege. J Immunol. 1998;160(12):5693–5966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rook AH, Kehrl JH, Wakefield LM, et al. Effects of transforming growth factor beta on the functions of natural killer cells: depressed cytolytic activity and blunting of interferon responsiveness. J Immunol. 1986;136(10):3916–3920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chauhan SK, Saban DR, Lee HK, et al. Levels of Foxp3 in regulatory T cells reflect their functional status in transplantation. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):148–153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rayner SA, Larkin DFP, George AJT. TNF receptor secretion after ex vivo adenoviral gene transfer to cornea and effect on in vivo graft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1568–1573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Comer RM, King WJ, Theoharis S, Ardjomand N, George AJT, Larkin DFP. Effect of administration of CTLA4-Ig as protein or cDNA on corneal allograft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1095–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klebe S, Sykes PJ, Coster DJ, Krishnan R, Williams KA. Prolongation of sheep corneal allograft survival by ex vivo transfer of the gene encoding interleukin-10. Transplantation. 2001;71(9):1214–1220. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200105150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klebe S, Coster DJ, Sykes PJ, et al. Prolongation of sheep corneal allograft survival by transfer of the gene encoding ovine IL-12-p40 but not IL-4 to donor corneal endothelium. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2219–2226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ritter T, Yang J, Dannowski H, Vogt K, Volk HD, Pleyer U. Effects of interleukin-12p40 gene transfer on rat corneal allograft survival. Transpl Immunol. 2007;18(2):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beutelspacher SC, Pillai RG, Watson MP, et al. Function of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in corneal allograft rejection and prolongation of allograft survival by over-expression. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:690–700. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gong N, Pleyer U, Vogt K, et al. Local overexpression of nerve growth factor in rat corneal transplants improves allograft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1043–1052. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bachmann BO, Bock F, Wiegand SJ, et al. Promotion of graft survival by vascular endothelial growth factor a neutralization after high-risk corneal transplantation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(1):71–77. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen L, Hamrah P, Cursiefen C, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 mediates induction of corneal alloimmunity. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):813–815. doi: 10.1038/nm1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Camelo S, Kezic J, McMenamin PG. Anterior chamber-associated immune deviation: a review of the anatomical evidence for the afferent arm of this unusual experimental model of ocular immune responses. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33(4):426–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamagami S, Dana MR. The critical role of lymph nodes in corneal alloimmunization and graft rejection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(6):1293–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Plskova J, Holan V, Filipec M, Forrester JV. Lymph node removal enhances corneal graft survival in mice at high risk of rejection. BMC Ophthalmol. 2004;4(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams KA, Esterman AJ, Bartlett C, Holland H, Hornsby NB, Coster DJ. How effective is penetrating corneal transplantation? Factors influencing long-term outcome in multivariate analysis. Transplantation. 2006;81(6):896–901. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000185197.37824.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chatel M-A, Larkin DFP. Sirolimus and mycophenolate as combination prophylaxis in corneal transplant recipients at high rejection risk. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.03.010. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams KA, White MA, Ash JK, Coster DJ. Leukocytes in the graft bed associated with corneal graft failure: analysis by immunohistology and actuarial graft survival. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:34–44. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nguyen NX, Martus P, Seitz B, Cursiefen C. Atopic dermatitis as a risk factor for graft rejection following normal-risk keratoplasty. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247(4):573–574. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0959-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Niederkorn JY, Chen PW, Mellon J, Stevens C, Mayhew E. Allergic airway hyperreactivity increases the risk for corneal allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(5):1017–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Beauregard C, Stevens C, Mayhew E, Niederkorn JY. Cutting edge: atopy promotes Th2 responses to alloantigens and increases the incidence and tempo of corneal allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):6577–6581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Flynn TH, Ohbayashi M, Ikeda Y, Ono SJ, Larkin DFP. The effect of allergic conjunctival inflammation on the allogeneic response to donor cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4044–4049. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]