Abstract

Chronically elevated levels of oxidative stress resulting from increased production and/or impaired scavenging of reactive oxygen species are a hallmark of mitochondrial dysfunction in left ventricular hypertrophy. Recently, oscillations of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) were mechanistically linked to changes in cellular excitability under conditions of acute oxidative stress produced by laser-induced photooxidation of cardiac myocytes in vitro. Here, we investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of ΔΨm within the intact heart during ischemia-reperfusion injury. We hypothesize that altered metabolic properties in left ventricular hypertrophy modulate ΔΨm spatiotemporal properties and arrhythmia propensity.

Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in response to elevated systemic pressure forms an adaptive and reversible mechanism that allows the heart to maintain cardiac output in the face of external stress. However, because LVH is associated with complex electrophysiological, structural, molecular, mechanical, and metabolic remodeling, it ultimately becomes a leading risk factor for heart failure, myocardial infarction, and ventricular arrhythmias (1).

Changes in mitochondrial energetics are a hallmark of hypertrophied and failing hearts (2–6). Numerous studies have shown that mitochondria are indeed central to the pathophysiology of the hypertrophied heart. For example, a marked shift in substrate utilization (free fatty acid to glucose) for energy production has been documented in various animal models and humans with hypertrophy (7). In addition, LVH is associated with mitochondrial structural deformities (8), including increased mitochondrial volume and disrupted mitochondrial network architecture. These fundamental changes, which alter the intricate regulation of myocardial bioenergetics, disrupt the balance between pro- and antioxidant pathways, and promote the activation of cell death pathways, contribute significantly to the progression of cardiac dysfunction and remodeling.

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is a key indicator of cellular viability because it reflects the capacity of the electron transport chain to pump hydrogen ions across the inner membrane, a requirement for oxidative phosphorylation and ATP generation (9,10). Chronic alterations in ΔΨm in various metabolic disorders cause cell death. Dynamic oscillations of ΔΨm produced by artificial conditions of oxidative stress in isolated cardiac myocytes can result in metabolic and electrophysiological oscillations that significantly impact myocyte function and lead to inexcitability at the cellular level by activating ATP-sensitive potassium channels (11–13). Furthermore, stabilization of ΔΨm using pharmacological interventions that inhibit the mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor can lead to action potential (AP) stabilization and prevention of arrhythmias in ex vivo perfused hearts subjected to ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury (11,14). As such, changes in ΔΨm are thought to modulate cellular electrophysiological changes that can scale to the level of the intact organ and affect excitability and arrhythmia propensity via a mechanism that Akar et al. (11) termed metabolic sink/block.

Despite correlative findings linking interventions that alter mitochondrial function in vitro to functional changes in vivo, a direct investigation of dynamic changes in ΔΨm at the level of the intact organ remains lacking because of technical challenges in measuring the spatiotemporal kinetics of ΔΨm across the intact heart. In this work, we developed a novel (to our knowledge), quantitative imaging technique for measuring the spatiotemporal dynamics of ΔΨm with subcellular resolution at the organ level. We then assessed dynamic changes in ΔΨm gradients during IR injury in normal and chronically diseased LVH hearts.

Materials and Methods

Pressure overload hypertrophy model

All procedures involving the handling of animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and adhered to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health. As previously described in detail (15,16), pressure overload LVH was produced in male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g) by ascending aortic banding. Briefly, 14 male rats underwent a right lateral thoracotomy to allow the placement of a 1-mm-diameter metallic clip around the ascending aorta. The animals were allowed to survive for 1 month after the procedure, which established an artificial aortic stenosis. We recently characterized the electrophysiological, mechanical, and structural changes that develop in this model of concentric hypertrophy (15). Thirteen normal rat hearts served as the control group.

Echocardiographic measurements

Echocardiography was performed under ketamine sedation (intraperitoneal, 60–100 mg/kg). Long- and short-axis views were obtained using a 14 MHz GE-i13L probe as recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography. Short-axis views were obtained as transverse sections of the LV at the mid-papillary level, and echocardiographic windows were selected to obtain circular images. The transducer position was carefully adjusted until the short-axis image of the LV cavity appeared to be circular, indicating perpendicular intersection of the LV by the ultrasonic beam. A 12MHz GE-10S probe was used to obtain apical four-chamber views. LV wall thickness and cavity dimensions were measured in systole and diastole with M-mode echocardiography. Additional measurements of the LV end-diastolic volume (EDV), end-systolic volume (ESV), stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF), and heart rate (HR) were also performed in all animals at baseline and after 4 weeks (time of sacrifice) of aortic banding or sham operation.

High-resolution optical ΔΨm imaging in ex vivo perfused rat hearts

The animals (n = 27) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg, IP). Their hearts were rapidly excised, washed with ice-cold cardioplegic solution, transferred to a Langendorff apparatus, and retrogradely perfused through the aorta with oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) Tyrodes solution containing (in mM) NaCl 121.7, NaHCO3 25, KCl 4.81, MgSO4 2.74, CaCl2 2.5, and dextrose 5.0, pH = 7.40, at a temperature of 36 ± 1°C. Perfusion pressure was maintained at ∼60 mmHg by adjusting perfusion flow. Volume-conducted electrocardiograms were recorded for rhythm analysis and arrhythmia scoring using noncontact silver electrodes (Grass Instruments) placed within the chamber. ECG signals, which were recorded continuously throughout the entire ex vivo perfusion protocol, were amplified (ECG100-MP150 amplifier; Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA) and displayed in real time using the AcqKnowledge 3.9 software package (Biopac Systems). The hearts were positioned such that the mapping field was centered over a 4 × 4 mm region of LV epicardium, midway between the apex and base (Fig. 1 A). These preparations remained stable for >4 h of perfusion. The ex vivo experimental protocol was typically completed in <2 h.

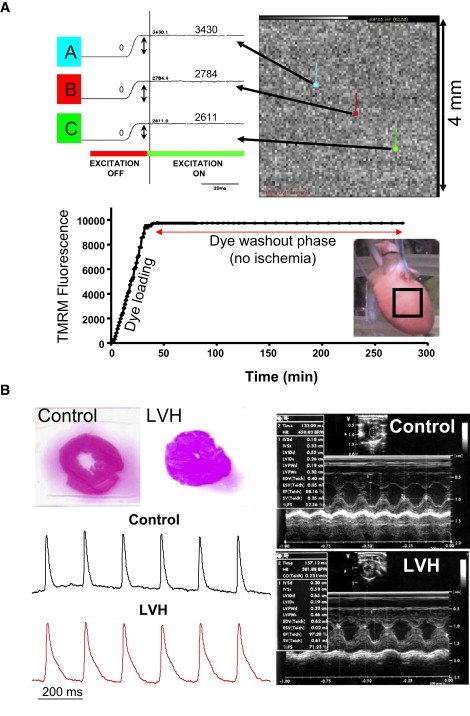

Figure 1.

(A) Three representative traces (A–C) from a total of 6400 pixels are shown indicating the measurement of background fluorescence used to monitor relative changes in ΔΨm. Also shown is the background fluorescence during and after (for up to 300 min) the dye-loading and washout procedures. These data demonstrate the stability of TMRM fluorescence during steady-state perfusion. The steady-state level of TMRM fluorescence for each pixel is used for normalization purposes. (B) Representative ECG images of a sham-operated and an aortic-banded LVH heart. H&E-stained histological sections from sham-operated and LVH hearts indicate marked concentric hypertrophy in aortic banded animals. Also shown are representative optical AP traces measured in representative di-4-ANEPPS-stained normal and LVH hearts during steady-state pacing.

We developed a novel (to our knowledge), semiquantitative imaging technique of optical ΔΨm mapping in ex vivo perfused guinea pig (17) and rat (18,19) hearts using the ΔΨm-sensitive dye TMRM. This method allows mitochondrial function to be assessed at a subcellular resolution within the intact organ (18,19). Briefly, after cannulation, the animals' hearts were allowed to stabilize for 20 min at physiological temperature (36 ± 1°C). They were then stained with TMRM (250 nM; Molecular Probes) mixed in a 500 mL volume of Tyrodes solution (dye-loading phase) for 20 min. This was followed by a 20–30 min dye washout phase during which perfusion was switched back to dye-free Tyrodes solution. TMRM background fluorescence intensity was measured periodically (in 1 min intervals) throughout the dye-staining and washout phases using a 6400 pixel CCD-based optical imaging approach that allowed the measurement of normalized ΔΨm with subcellular resolution (50μm) over a 4 × 4 mm window of the epicardial surface. To measure TMRM background fluorescence, the hearts were excited with filtered light (525 ± 20 nm) emitted from a quartz tungsten halogen lamp (Newport Corp., Goleta, CA). Emitted fluorescence was filtered (585 ± 20 nm for TMRM) and focused onto the high-resolution CCD camera (Scimeasure, Decatur, GA). Background fluorescence intensity was measured as the amplitude difference before and after excitation (Fig. 1 A).

During the dye-loading procedure, a marked rise in background fluorescence was verified for multiple pixels to confirm adequate dye staining of the heart (Fig. 1 A). During dye washout, the stability of TMRM background fluorescence was evaluated from multiple pixels in real time, as this baseline level served for normalization purposes during the IR protocol. In all experiments, the dye washout phase was associated with stable signal intensity, which was required to normalize subsequent changes in TMRM fluorescence caused by IR injury. In preliminary experiments, we ensured the stability of background fluorescence for >3 h of steady-state perfusion (Fig. 1 A).

High-throughput analysis of optical signals was performed using the CardioPlex software v.8.3.3 (RedShirt Imaging, Decatur, GA). The peak emitted TMRM fluorescence signal from each of 6400 pixels was measured before and after excitation achieved by a computer-automated filter shutter switch. TMRM background fluorescence was baseline corrected by subtracting fluorescence levels before dye staining (<0.1%) for each pixel. Background-corrected TMRM fluorescence (ΔΨm) during the IR protocol was then normalized to the value of steady-state TMRM fluorescence achieved during the dye washout phase for each of the 6400 individual pixels.

Normalized ΔΨm measurements during IR injury across the imaged 4 × 4 mm region of the heart were plotted as contour maps using Delta Graph 5.6 (Red Rock Software, Salt Lake City, UT). These maps served to illustrate the dynamic changes in the spatial distribution of ΔΨm.

IR injury in normal and hypertrophied hearts

IR injury promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress (13,20,21). Therefore, we used a protocol of global no-flow ischemia (for 7 min), followed by reperfusion in normal and LVH hearts. In preliminary experiments, we determined that this moderate protocol (i.e., 7 min of ischemia) produced sustained reperfusion arrhythmias in <50% of control hearts. Therefore, this protocol allowed us to determine whether LVH was associated with a heightened susceptibility to IR-mediated arrhythmias. ΔΨm recordings were performed in 10-s intervals throughout the first minute of reperfusion, when rapid changes were most likely to occur, and at 1-min intervals throughout the remaining time.

The propensity for spontaneous arrhythmias was scored according to the guideline described by Walker et al. (22) using the Lambeth Conventions. Briefly, the following criteria were used to generate an arrhythmia score (AS) for each unpaced control and LVH heart: 0 = <50 ventricular premature beats; 1 = 50–499 ventricular premature beats; 2 = >500 ventricular premature beats and/or one episode of spontaneously reverting VT/VF; 3 = more than one episode of spontaneously reverting VT/VF (<1 min total combined duration); 4 = 1–2 min of total combined VT/VF; and 5 = >2 min of VT/VF. AS was measured during ischemia and reperfusion in all normal and LVH hearts.

In addition, we used a series of control (n = 4) and LVH (n = 4) animals to investigate potential differences in the incidence of complex arrhythmias (VT/VF, AS ≥ 3) occurring in hearts that had undergone ex vivo steady-state pacing (4 Hz) during IR injury.

Results

Structural, mechanical, and electrophysiological remodeling in LVH

Four weeks of pressure overload led to marked changes in structural and functional parameters (Fig. 1 B and Table 1), consistent with concentric LVH. Shown in Fig. 1 B are representative echocardiograms (right) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained histological cross sections (left) from representative sham-operated and LVH animals, indicating the presence of marked concentric hypertrophy in banded animals. As shown in Table 1, standard metrics of wall thickness measured in systole (interventricular septal width in systole (IVSs) and left ventricular posterior wall in systole (LVPWs)) and diastole (interventricular septal width in diastole (IVSd) and left ventricular posterior wall in diastole (LVPWd)) were significantly (p < 0.001) increased by 50–75% over baseline values. Fractional shortening (FS) increased by 29% (p < 0.001), whereas ESV decreased by 67% (p < 0.001). HR, SV, and cardiac output remained stable. Also consistent with hypertrophic remodeling, optical AP mapping in a subset of di-4-ANEPPS-stained control (n = 4) and LVH (n = 4) hearts revealed a significant increase in APD in LVH. Representative AP traces from control (black) and LVH (red) hearts during steady-state pacing are shown in Fig. 1 B (left).

Table 1.

Results of statistical analyses of structural and mechanical indices of echocardiographic measurements at baseline and after 4 weeks of LVH

| Preoperative |

1 Month postoperative |

% Change | Paired t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| HR (bpm) | 427.29 | 55.90 | 395.44 | 36.36 | −6.25 | p = 0.0694 |

| IVSD (cm)∗ | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 75.95 | p < 0.0001 |

| IVSS (cm)∗ | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 63.86 | p < 0.0001 |

| LVIDd (cm) | 0.63 | 0.05 | 0.64 | 0.10 | 0.82 | p = 0.82 |

| LVIDs (cm)∗ | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.08 | −40.23 | p < 0.0001 |

| LVPWd (cm)∗ | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 64.07 | p < 0.0001 |

| LVPWs (cm)∗ | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 49.55 | p < 0.0001 |

| EDV (mL) | 0.60 | 0.13 | 0.64 | 0.25 | 5.21 | p = 0.39 |

| ESV (mL)∗ | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −67.40 | p < 0.0001 |

| EF (%)∗ | 91.75 | 3.30 | 97.62 | 2.07 | 6.50 | p < 0.0001 |

| SV (mL) | 0.54 | 0.11 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 12.45 | p = 0.15 |

| FS (%)∗ | 59.04 | 5.91 | 76.02 | 10.19 | 29.83 | p = 0.0002 |

| CO (mL/min) | 427.29 | 55.90 | 395.44 | 36.36 | −6.25 | p = 0.64 |

LVIDd: left ventricular internal dimension in diastole; LVIDs: left ventricular internal dimension in systole.

Indicates statistical significance p < 0.05.

Metabolic remodeling in LVH: paradoxical stability of ΔΨm during ischemia

As shown in Fig. 2 A, ischemia caused a rapid and sustained decline (depolarization) of normalized ΔΨm in control hearts. Within 1 min of ischemia, normalized ΔΨm was reduced by 26% compared to preischemic baseline levels. ΔΨm was further decreased to ∼50% of baseline by 4 min of ischemia and was sustained at that level throughout the remaining ischemic episode. Of interest, reperfusion led to a rapid and sustained repolarization of ΔΨm. In a subset of studies, we found that reperfusion after longer (15 min) episodes of ischemia could only transiently repolarize ΔΨm (not shown) (19). Since these hearts exhibited reperfusion VF in almost all cases, we chose a milder IR injury protocol to study potential differences between control and LVH hearts.

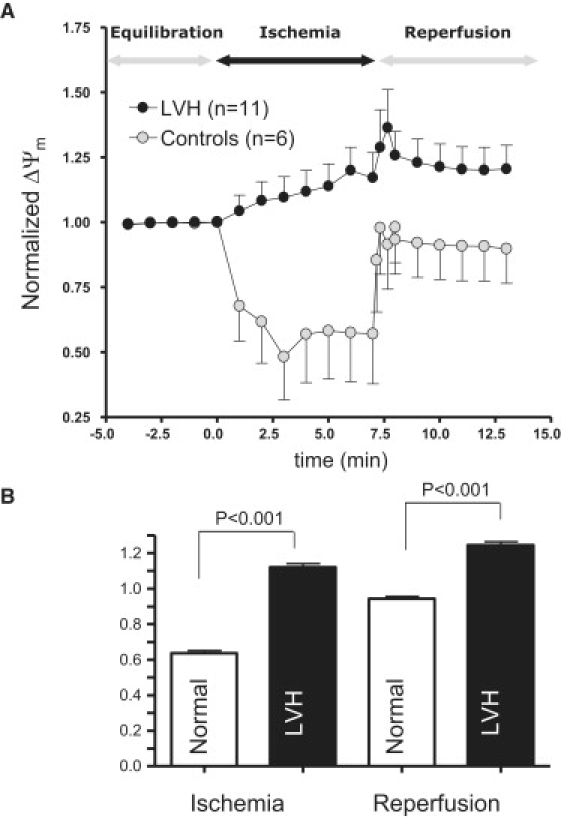

Figure 2.

(A) Average and SD of ΔΨm response to IR injury in normal and LVH hearts. Clearly, LVH prevents ischemia-induced depolarization of ΔΨm. (B) Average ΔΨm response during the entire episode of ischemia (over 7 min) and reperfusion in normal and LVH hearts. LVH is associated with a significantly more polarized ΔΨm during both ischemia and reperfusion.

In sharp contrast, LVH hearts were resistant to ischemia-induced ΔΨm depolarization (Fig. 2 A, black symbols). On average, ΔΨm was significantly increased (by 17%, p = 0.0082) rather than decreased during ischemia compared to baseline levels (Fig. 2 A). Furthermore, the paradoxical increase in ΔΨm observed during ischemia was sustained after reperfusion in LVH (Fig. 2 A). The marked differences in average ΔΨm between control and LVH hearts during ischemia and reperfusion are also quantified in Fig. 2 B. Clearly, average normalized ΔΨm was significantly (p < 0.001) greater during both ischemia and reperfusion compared to control hearts.

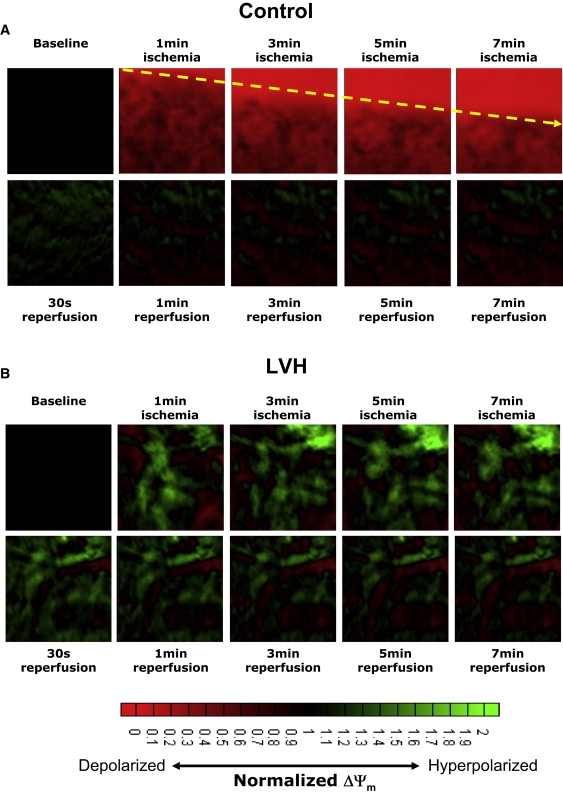

In addition to the average ΔΨm, we measured the spatiotemporal patterns of ΔΨm during ischemia and reperfusion. Shown in Fig. 3 are contour maps recorded at various time points during the course of ischemia (top row) and reperfusion (bottom row) in control (Fig. 3 A) and LVH (Fig. 3 B) hearts. It is evident that ischemia led to a rapid (within 1 min) depolarization of ΔΨm in the control heart. Of interest, these contour maps reveal the formation of an organized wavefront of ΔΨm depolarization that actively propagated during the course of ischemia (arrow) across the control heart. As mentioned above, reperfusion led to a rapid and sustained repolarization of ΔΨm across the entire mapping field. Although on average, ΔΨm failed to depolarize during ischemia in LVH, an examination of the spatiotemporal changes in ΔΨm revealed the presence of complex neighboring regions of increased (green) and decreased (red) ΔΨm. These regions of opposite ΔΨm polarity compared to baseline were relatively static and did not exhibit major fluctuations throughout the entire ischemic episode (Fig. 3 B). This was in contrast to control hearts, in which ischemia led to the active propagation of a wave of ΔΨm depolarization that progressively captured more myocardium (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 3.

Contour maps showing the spatiotemporal distribution of ΔΨm during the course of ischemia (top row) and reperfusion (bottom row) in representative normal (A) and LVH (B) hearts.

Spatial heterogeneity of ΔΨm in control and LVH hearts

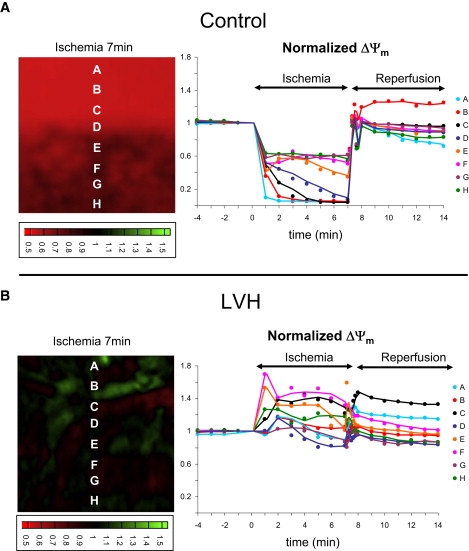

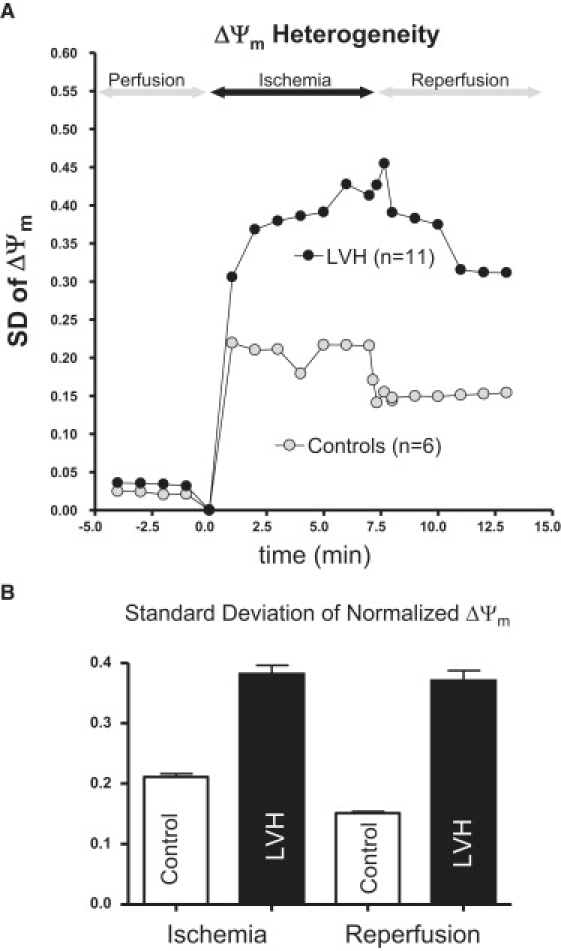

Because LVH hearts were distinguished by the presence of spatially adjacent regions of increased and decreased ΔΨm, we systematically investigated the degree of ΔΨm heterogeneity in all control and LVH hearts during the course of IR injury. Shown in Fig. 4 are representative ΔΨm contour maps recorded after 7 min of ischemia, and select ΔΨm traces measured during the course of IR injury (sites A–H). Clearly, the control hearts exhibited distinct ΔΨm depolarization during ischemia (Fig. 4 A, sites A–H). In contrast, LVH was marked by heterogeneous ΔΨm responses with depolarizing and hyperpolarizing sites (Fig. 4 B). The extent of ΔΨm heterogeneity was quantified as the SD of normalized ΔΨm measured from 6400 pixels during IR injury in control (n = 6) and LVH (n = 11) hearts (Fig. 5). At all time points during the IR protocol, LVH was associated with increased ΔΨm heterogeneity compared to control hearts (Fig. 5 A). In fact, on average, ΔΨm heterogeneity was significantly greater during ischemia (by 80.8%, p < 0.0001) and reperfusion (144.9%, p < 0.001) in LVH compared to control hearts (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 4.

ΔΨm contour maps recorded after 7 min of ischemia in representative normal (A) and LVH (B) hearts. (Right) Multiple traces recorded from the same normal and LVH hearts during the course of IR injury.

Figure 5.

(A) Spatial heterogeneity indexed by the SD of ΔΨm in normal and LVH hearts. (B) Average and SD of ΔΨm heterogeneity measured during ischemia and reperfusion in normal and LVH hearts.

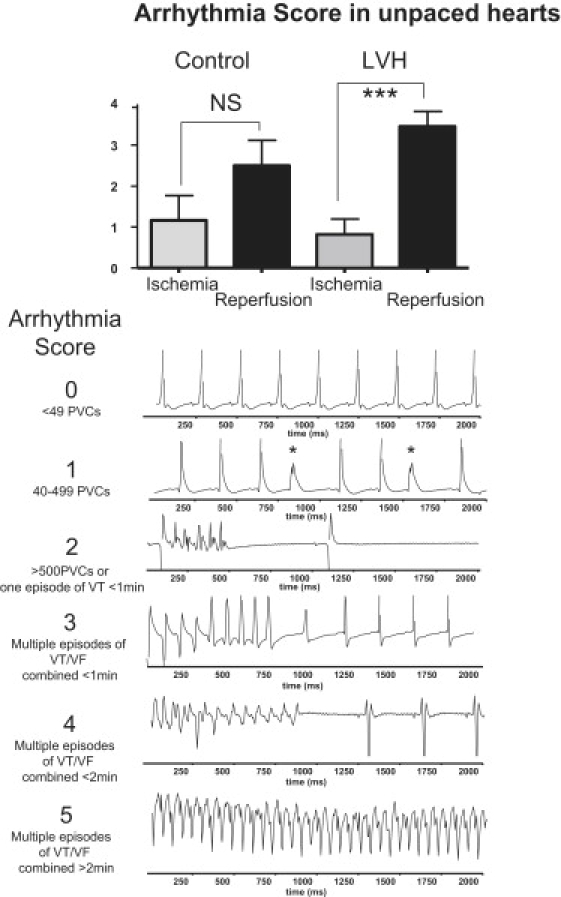

Enhanced susceptibility of hypertrophied hearts to reperfusion-mediated arrhythmias

We then investigated potential differences in the propensity of control and LVH hearts to IR-mediated arrhythmias. We first calculated the AS values from the continuous ECG recordings performed in all hearts. Shown in Fig. 6 are average AS values during ischemia and reperfusion of control and LVH hearts (top) and representative ECG traces indicating various levels of arrhythmia complexity, and reflecting the range of AS values from normal rhythm (AS = 0) to sustained VT/VF (AS = 5) (bottom). Of note, the average AS values were comparable during ischemia in both unpaced control and LVH hearts (p = NS). Reperfusion, on the other hand, caused a significant increase in AS in LVH (p < 0.001) but not control (p = 0.082) hearts.

Figure 6.

AS as an index of spontaneous arrhythmias measured during ischemia and reperfusion from all unpaced normal and LVH hearts. Representative ECG traces indicate progressively more complex arrhythmias, ranging from AS 0 to 5. AS: arrhythmia score.

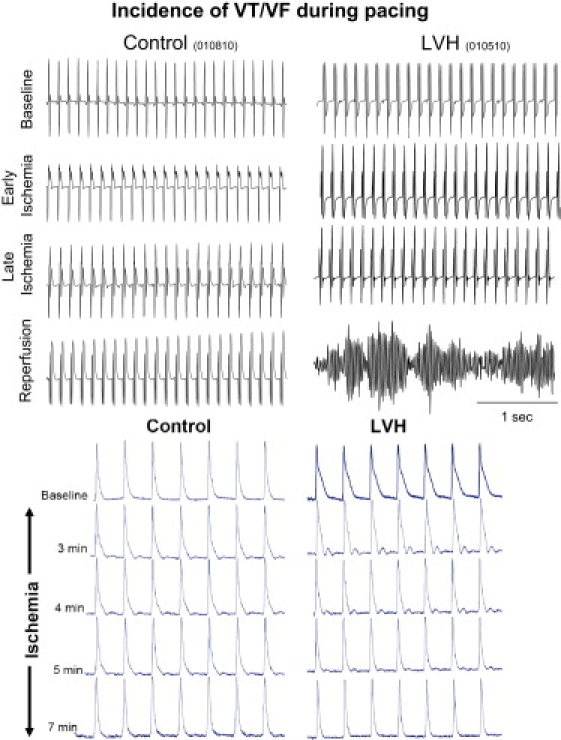

An additional series of eight hearts (four control and four LVH) were used to investigate potential differences in the incidence of complex arrhythmias during ex vivo pacing (at 4 Hz) and IR injury. Shown in Fig. 7 are representative volume-conducted ECG traces from control (left) and LVH (right) hearts. Of interest, steady-state pacing during IR injury revealed the presence of arrhythmias in LVH (2/4) but not (0/4) control hearts (Fig. 7). Finally, 7 min of ischemia resulted in rapid shortening of APD90 in LVH but not control hearts (Fig. 7, bottom).

Figure 7.

Incidence of VT/VF in paced hearts during IR injury. Representative volume-conducted ECG traces measured at baseline, during early and late ischemia, and after reperfusion in control (left) and LVH (right) hearts. VT/VF was observed exclusively in paced LVH hearts. Representative AP traces from control and LVH hearts demonstrate rapid shortening of APD in LVH but not control hearts in response to 7 min of ischemia (bottom).

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate the feasibility of measuring the spatiotemporal dynamics of ΔΨm across the intact organ during IR injury. The major findings of this study are as follows: 1) Ischemia generated a wave of active ΔΨm depolarization across control but not hypertrophied hearts. 2) Complex areas of ΔΨm depolarization and hyperpolarization coexisted across the hypertrophied heart during the entire course of ischemia. 3) The spatial heterogeneity of ΔΨm was significantly greater in LVH than in control hearts during both ischemia and reperfusion. 4) Hypertrophied hearts were more sensitive to IR-mediated arrhythmias compared to control hearts.

Disrupted ΔΨm depolarization in LVH during IR injury

One of the main contributions of this study is the identification of spatiotemporal changes in ΔΨm at a subcellular resolution within the intact organ. We found that ΔΨm, measured in native myocardium, underwent marked changes during IR injury. Our finding of ΔΨm depolarization over a 4 × 4 mm area during ischemia is consistent with the elegant findings of Matsumoto-Ida et al. (23), who used two-photon microscopy to image a 50 μm region. More recently, Slodzinski et al. (24) showed heterogeneous ΔΨm depolarization within the intact guinea pig heart that was associated with increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and depletion of intracellular glutathione levels. Remarkably, our findings indicate that reperfusion after 7 min of global no-flow ischemia in the rat results in complete and sustained recovery of ΔΨm after reperfusion.

Another major finding of this work is that LVH paradoxically disrupts progressive ΔΨm depolarization observed during the course of ischemia in the control heart. Our findings regarding disrupted ΔΨm polarization in LVH are consistent with earlier reports indicating that hypertrophy is associated with marked baseline alterations of ΔΨm at the cellular level. Previous measurements of ΔΨm in hypertrophy have yielded disparate results. Notably, Sharma et al. (25) demonstrated that LVH in guinea pigs is associated with a basal reduction of ΔΨm. In contrast, Nagendran and colleagues (26) reported an increase of ΔΨm in phenylephrine-treated rat neonatal cardiomyocytes, adult rat hearts from animals with monocrotaline induced pulmonary hypertension, and human tissue samples from patients with right ventricular hypertrophy undergoing cardiac surgery (26). Both groups compared the total fluorescence of mitochondrial dyes (TMRM or JC1) during steady state, whereas our approach allowed the measurement of dynamic spatiotemporal changes in ΔΨm relative to baseline during IR injury. It is worth noting that in the study by Sharma et al. (25), animals were examined at a more advanced stage of the disease (10 weeks after aortic banding), which reflected the transition point from cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure.

Nagendran and colleagues (26) linked the increase in ΔΨm to changes in pyruvate metabolism, whereas Sharma et al. (25) emphasized the activation of apoptotic pathways through ROS. A major consequence of ROS accumulation involves alterations in the function of mitochondrial ion channels, such as the permeability transition pore (PTP) and the inner membrane mitochondrial ion channel (IMAC). Aon and colleagues (27) elegantly showed that the glutathione redox couple (GSH/GSSG) of the cardiac cell governs the sequential opening of these channels, with reversible IMAC activation occuring before irreversible PTP opening. Of interest, PTP opening during calcium stress is more likely in hypertrophied compared to control hearts (28). Others have described changes in ion fluxes that may protect against the loss of ΔΨm. The activity of the newly discovered mitochondrial calcium channels (mCa1 and mCa2) was shown to be significantly reduced in end-stage human heart failure, resulting in lower mitochondrial calcium influx and stabilized ΔΨm (29). Moreover, the development of hypertrophy is associated with marked changes in the expression of uncoupling proteins, which are known to regulate ΔΨm and ROS generation. In fact, our finding of ΔΨm hyperpolarization in LVH is consistent with the down-regulation of uncoupling proteins that has been observed in animal models and humans with hypertrophy (30).

In this study, we demonstrate how mitochondria within their native environment can react differentially to the same acute stressor (IR injury) in chronically diseased compared to control hearts. The altered polarization patterns of ΔΨm in hypertrophy could represent an adaptive mechanism with beneficial or deleterious physiological consequences. Both elevations and depressions of ΔΨm can lead to increased ROS production (31). An increase in ΔΨm, for example, may provide a protective mechanism against apoptosis, a process that is considered to be central in the transition from compensated hypertrophy to end-stage heart failure. On the other hand, increased ΔΨm may also interfere with mitochondrial substrate transport and respiration, and thus may underlie some of the adverse metabolic remodeling observed in hypertrophy.

Increased ΔΨm heterogeneity in LVH

In addition to allowing the measurement of average changes in ΔΨm, our technique is also well suited for detailed investigations of the spatiotemporal dynamics of ΔΨm across a relatively large (4 × 4 mm) region of the epicardial surface. We observed a spatially complex distribution of polarized and depolarized regions of ΔΨm in hypertrophied hearts that were not present in control hearts during ischemia.

Since the mitochondrial function of individual cells is highly influenced by network properties, it is critical to investigate subcellular mitochondrial function within the milieu of the intact heart. Specifically, our findings indicate a heterogeneous metabolic substrate across the heart during IR injury. These heterogeneities may ultimately modulate myocardial excitability and contribute to the formation of zones of conduction block by heterogeneous activation of surface ATP-sensitive potassium channels (11,32). As such, these metabolic heterogeneities are consistent with the notion of metabolic sink/block recently suggested by Akar and colleagues (11).

Heightened susceptibility of LVH hearts to reperfusion-mediated arrhythmias

Sustained arrhythmias caused by oxidative stress associated with IR injury are known to occur during early reperfusion. Indeed, we found that spontaneously arising arrhythmic events (quantified by an AS index) were significantly greater during reperfusion compared to ischemia in LVH but not control hearts, implicating oxidative stress in the mechanism of these arrhythmias. Moreover, our finding that complex arrhythmias (VT/VF) in paced hearts were exclusively present in LVH but not control hearts undergoing IR injury further highlights the susceptibility of LVH hearts to arrhythmias, even when HR is controlled. Although hypertrophy is characterized by complex structural, mechanical, and electrophysiological alterations that render the heart more vulnerable to arrhythmias (15), our findings highlight a potentially critical role for metabolic remodeling in general, and altered ΔΨm properties in particular, in the mechanism of these arrhythmias.

Finally, we previously showed that partial blockade of IMAC, which in isolated myocytes can stabilize ΔΨm, is an effective tool for preventing reperfusion-mediated VT/VF in guinea pigs (11). Our current findings indicate that increased ΔΨm during ischemia in LVH promotes rather than prevents arrhythmias upon reperfusion. These apparently contradictory findings suggest that there might indeed be a delicate balance of ΔΨm changes that can either promote or prevent arrhythmias. Of interest, the highest concentration of IMAC blocker (4′-Cl-DZP) in our previous study (100 μM), which effectively prevented the formation of inexcitability (electrical silence) throughout the entire ischemic period, was not effective in suppressing reperfusion-mediated arrhythmias, in contrast to lower concentrations (64 μM) (11). This is consistent with our present findings that complete abrogation of ΔΨm depolarization during metabolic stress associated with ischemic injury is indeed pro-arrhythmic.

Limitations

Ischemic injury results in highly complex electrophysiological changes that ultimately render the heart prone to arrhythmias. In this work, we focused on a key metric of mitochondrial function (ΔΨm) that drives the electron transport chain by setting the electromotive force. In humans and animal models, IR-related arrhythmias are dependent on multifactorial mechanisms such as changes in ion gradients (hyperkalemia, sodium and calcium overload), acidosis, and gap junction uncoupling. Therefore, one should not expect that a single metric of cardiac function will fully predict arrhythmias in this setting. However, our present findings strongly implicate mitochondrial dysfunction in general, and disrupted ΔΨm kinetics during ischemia in particular, as an important mechanism of arrhythmias in LVH.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants to F.G.A. from the American Heart Association (0830126N); the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (HL091923); the Irma T. Hirschl and Monique Weill Caullier Trusts; and the Celladon Corporation.

References

- 1.Kang Y.J. Cardiac hypertrophy: a risk factor for QT-prolongation and cardiac sudden death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2006;34:58–66. doi: 10.1080/01926230500419421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanley W.C., Chandler M.P. Energy metabolism in the normal and failing heart: potential for therapeutic interventions. Heart Fail. Rev. 2002;7:115–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1015320423577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanley W.C., Recchia F.A., Lopaschuk G.D. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:1093–1129. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huss J.M., Kelly D.P. Mitochondrial energy metabolism in heart failure: a question of balance. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:547–555. doi: 10.1172/JCI200524405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingwall J.S. Energy metabolism in heart failure and remodelling. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;81:412–419. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsutsui H., Kinugawa S., Matsushima S. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunction in myocardial remodelling. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;81:449–456. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leong H.S., Brownsey R.W., Allard M.F. Glycolysis and pyruvate oxidation in cardiac hypertrophy—why so unbalanced? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2003;135:499–513. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(03)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kayar S.R., Weiss H.R. Diffusion distances, total capillary length and mitochondrial volume in pressure-overload myocardial hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1992;24:1155–1166. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)93179-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustafsson A.B., Gottlieb R.A. Heart mitochondria: gates of life and death. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008;77:334–343. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Rourke B. Mitochondrial ion channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2007;69:19–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.163804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akar F.G., Aon M.A., O'Rourke B. The mitochondrial origin of postischemic arrhythmias. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:3527–3535. doi: 10.1172/JCI25371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aon M.A., Cortassa S., O'Rourke B. Synchronized whole cell oscillations in mitochondrial metabolism triggered by a local release of reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:44735–44744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honda H.M., Korge P., Weiss J.N. Mitochondria and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1047:248–258. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown D.A., Aon M.A., O'Rourke B. Effects of 4′-chlorodiazepam on cellular excitation-contraction coupling and ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rabbit heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008;79:141–149. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin H., Chemaly E.R., Akar F.G. Mechanoelectrical remodeling and arrhythmias during progression of hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2010;24:451–463. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Monte F., Butler K., Hajjar R.J. Novel technique of aortic banding followed by gene transfer during hypertrophy and heart failure. Physiol. Genomics. 2002;9:49–56. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00035.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akar F.G., Miguel A.A., O'Rourke B. Spatial heterogeneity of the mitochondrial membrane potential underlies reperfusion related arrhythmias. Circulation. 2006;114:II269. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin H., Chemaly E.R., Akar F.G. Spatial heterogeneity of the mitochondrial membrane potential underlying arrhythmias in pressure overload hypertrophy. Circulation. 2008;118:S531. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyon A.R., Park J., Akar F.G. Gene transfer of the peripheral type benzodiazepine receptor alters the spatio-temporal dynamics of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ(M)) across the intact heart. Circulation. 2008;118:S528. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan G.C., Zhou X., Kranias E.G. Heat shock protein 20 interacting with phosphorylated Akt reduces doxorubicin-triggered oxidative stress and cardiotoxicity. Circ. Res. 2008;103:1270–1279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao W., Fan G.C., Kranias E.G. Protection of peroxiredoxin II on oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte death and apoptosis. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2009;104:377–389. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0764-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker M.J., Curtis M.J., Woodward B. The Lambeth Conventions: guidelines for the study of arrhythmias in ischaemia infarction, and reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 1988;22:447–455. doi: 10.1093/cvr/22.7.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto-Ida M., Akao M., Kita T. Real-time 2-photon imaging of mitochondrial function in perfused rat hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 2006;114:1497–1503. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slodzinski M.K., Aon M.A., O'Rourke B. Glutathione oxidation as a trigger of mitochondrial depolarization and oscillation in intact hearts. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2008;45:650–660. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma A.K., Dhingra S., Singal P.K. Activation of apoptotic processes during transition from hypertrophy to heart failure in guinea pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H1384–H1390. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00553.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagendran J., Gurtu V., Michelakis E.D. A dynamic and chamber-specific mitochondrial remodeling in right ventricular hypertrophy can be therapeutically targeted. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008;136:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aon M.A., Cortassa S., O'Rourke B. Sequential opening of mitochondrial ion channels as a function of glutathione redox thiol status. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:21889–21900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702841200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matas J., Young N.T., Burelle Y. Increased expression and intramitochondrial translocation of cyclophilin-D associates with increased vulnerability of the permeability transition pore to stress-induced opening during compensated ventricular hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009;46:420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michels G., Khan I.F., Hoppe U.C. Regulation of the human cardiac mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by 2 different voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Circulation. 2009;119:2435–2443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.835389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laskowski K.R., Russell R.R. Uncoupling proteins in heart failure. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2008;5:75–79. doi: 10.1007/s11897-008-0013-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turrens J.F. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J. Physiol. 2003;552:335–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss J.N., Venkatesh N. Metabolic regulation of cardiac ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 1993;7:499–505. doi: 10.1007/BF00877614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]