Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess sporting and physical activities in patients who had undergone hip resurfacing. Our study included 117 patients who underwent hip resurfacing between 2003 and 2008. University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) activity level and Oxford hip scores (OHS) were used. Sporting and physical activities of all patients were analysed pre- and postoperatively. The mean age at surgery was 54 years. The mean follow up was 30 months. There was statistically significant improvement in UCLA activity scores from 4.4 to 6.8 (p < 0.05) and Oxford hip scores from 43.4 to 17.7 following surgery. Eighty-seven percent of patients continued to take part in sporting activities following hip resurfacing. Our study has demonstrated that hip resurfacing can allow patients to remain extremely active.

Introduction

For more than 30 years total hip arthroplasty has been the gold standard for the management of osteoarthritis of the hip. The principles of surgery are to decrease pain and correct deformity, both of which aim to improve function. In young active patients, restoration of function is often a primary reason for hip arthroplasty [1]. Increasingly the desire for improvement of function often includes an aspiration to return to sporting activity. The participation in sports following total hip arthroplasty has been investigated [2]. The advent of hip resurfacing has added a new dimension to the management of osteoarthritis in younger patients. The medium-term survivorship of hip resurfacing implants has been encouraging [3, 4]. Hip resurfacing is a bone preserving procedure that maintains the normal biomechanics of the native hip. This key feature of hip resurfacing reduces pain and improves function whilst at the same time preserving stability of the hip. Younger and more active patients are now undergoing hip resurfacing. To date we have found only limited studies in the published literature that has looked at sporting activities of this group [5, 6]. In addition the recommendations for physical activities of such patients are poorly defined. This study was conducted to evaluate the sporting and physical activities, and analyse functional outcomes of patients undergoing hip resurfacing for osteoarthritis of the hip.

Materials and methods

Between 2003 and 2008, 119 patients who underwent hip resurfacing in our hospital were studied. During the course of this study two patients died. Both deaths were not related to the operations performed. Nineteen patients had bilateral hip resurfacing procedures giving a total of 136 hips. Demographic data including age, sex, occupation and comorbidities were recorded. History of previous hip surgery was also noted.

Patients’ physical activity was assessed using the 10-point University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) activity-level scale (Table 1). The UCLA scale is a convenient and reliable way of evaluating patient activity following joint replacement [7]. Recent studies have suggested that the UCLA scoring system has the best reliability when assessing outcome in patients undergoing joint replacement surgery [8].

Table 1.

University of California and Los Angeles activity-level rating scale

| Level | Activity |

|---|---|

| 10 | Regular participation in impact sports such as tennis, skiing, acrobatics, ballet, heavy labour or backpacking |

| 9 | Sometimes participates in impact sports |

| 8 | Regular participation in very active events, such as bowling or golf |

| 7 | Regular participation in active events, such as bicycling |

| 6 | Regular participation in moderate activities, such as swimming and unlimited housework and shopping |

| 5 | Sometimes participates in moderate activities |

| 4 | Regular participation in mild activities, such as walking, limited house work, and limited shopping |

| 3 | Sometimes participates in mild activities |

| 2 | Mostly inactive: restricted to minimal activities of daily living |

| 1 | Wholly inactive: dependent on others; cannot leave residence |

Patients were also assessed using the 12-point Oxford hip scoring system. The hip scores in this system range from 12 to 60, with a lower score representing a good result. A score between 12 and 20 implies good joint function. This system is well validated and reproducible [9]. Pre- and postoperative visual analogue scores (VAS) were obtained for each patient. The sporting and physical activities of all patients pre- and postoperatively were recorded. The key outcome measure of this study was to discover whether patients were able to successfully return to their regular sporting activity. We defined regular activity as participating in a chosen sport/activity at least once a month. All data was computerised and analysed.

The prosthesis in 82 patients was the Birmingham hip resurfacing system (Smith and Nephew). In the remaining 35 patients the MITCH resurfacing system (Stryker) was used. All operations were performed by the two senior authors as per the manufacturer’s guidelines. A posterior or an anterolateral approach was used. Patients received a total of three doses of intravenous cefuroxime and a once daily dose of subcutaneous low molecular heparin until discharge. Patients were encouraged to mobilise fully weight bearing on the first postoperative day using a Zimmer frame. Patients gradually made the transition from two elbow crutches to one walking stick before discharge. After six weeks in the outpatient physiotherapy department, patients were taught a range of movement exercises for the hip and encouraged to gradually increase their activities. Patients were advised to swim or undertake low impact exercises in the gym. Patients were advised against high impact activities during the first six months following surgery. Routine follow-up was arranged for all patients at six weeks, three months, 12 months and annually thereafter.

Results

The mean age at surgery was 54 years (range 30–73) and 56 years at review. The mean follow-up time was 30 months (range 16–50 months). The gender distribution was 67 males and 50 females.

UCLA scores

Activity levels were determined for each patient using the UCLA activity scoring system (Table 1). A preoperative and postoperative score was obtained for each patient. The mean preoperative UCLA score was 4.4 (range 1–10) and median was 4. The mean postoperative UCLA score mean was 6.8 (range 3–10) and median was 6. There was a significant improvement in postoperative UCLA scores (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, p < 0.01).

Oxford hip scores

We used the Oxford hip scoring system to assess hip symptoms and function. The mean preoperative Oxford hip score was 43.4 and mean postoperative score was 17.7.

VAS scores

Visual analogue scores were used to assess pain levels before and after surgery. The mean preoperative VAS score was 8.5 and the mean postoperative score was 1.7.

Sporting and physical activities

Of the 117 patients in the study group 31 never took part in sporting activities. In the remaining 86 patients 75 of them (87%) successfully returned to sporting activities following hip resurfacing. Eleven patients (13%) were unable to return to their sporting activities. It is interesting to note that ten patients (32%) from the group that never took part in sporting activities prior to surgery were able to take up sporting activities following surgery.

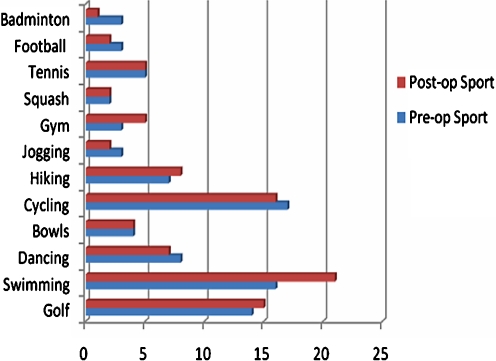

The key sports and physical activities that patients were undertaking pre- and postoperatively are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Patients participating in various sports before and after surgery

Complications

Following surgery, six patients developed superficial wound infections which resolved with antibiotics. There were no cases of deep infection. Four patients required treatment for deep venous thrombosis. One patient developed a pulmonary embolus requiring anticoagulation. One patient developed a foot drop following surgery. In the course of this study there were no episodes of dislocation or periprosthetic fracture.

Discussion

Hip arthroplasty in the younger and more active patients has been a major challenge for orthopaedic surgeons for several decades. One of the major success stories in modern hip surgery has been the management of osteoarthritis of the hip in young active patients by hip resurfacing. The published medium-term survivorship of the Birmingham hip has given surgeons increasing confidence to use resurfacing in younger patients [10]. Findings from our study suggest that these patients are very active and a large proportion regularly participate in sports. Following surgery the vast majority of patients were able to resume their regular sporting activity without significant impairment.

One study has also looked at sporting and physical activities following hip resurfacing [6]. In a series of 43 patients it was shown that 65% of patients participated in sports before surgery and this increased to 92% following surgery. In our study 87% of patients successfully returned to sporting activities following surgery. Our study has shown that sporting activity can be maintained following hip resurfacing.

We used pre- and postoperative UCLA and Oxford hip scores as secondary outcome measures to quantify functional outcomes. The majority of patients in our study were participating in low impact sports with a significant number of patients able to participate in high impact sports including tennis, squash, football and badminton following surgery.

In recent years knowledge of the effects of sports activity on patients with joint replacements has increased. However, there is still considerable debate about the long-term effects of high physical activity on prosthetic wear, loosening and revision rates. Some studies have shown that in younger, more active patients the incidence of loosening and failure of conventional total hip arthroplasties is higher [11–13]. In these studies the premature failure was attributed to aseptic loosening from increased polyethylene wear. With a metal-on-metal bearing surface several in vitro studies have shown the wear characteristics to be much more favourable [14–16].

A stable hip is paramount to any patient who wishes to return to sports. When considering the biomechanics of hip resurfacing to a conventional total hip arthroplasty there are several characteristics of hip resurfacing that may provide more stability to the hip. A large head diameter increases the head to neck ratio, which in turn allows for an increased arc of motion. Excursion distance is also increased with the use of a large head articulation thus providing an innate stability which may reduce the incidence of dislocation [10]. It is of note that during the course of this study there were no episodes of dislocation.

The benefits of regular sporting activity for any patient following hip replacement surgery cannot be underestimated. Regular exercise is associated with increased cardiac reserve and lowering of systemic blood pressure [17]. Increased physical activity also helps to maintain good bone stock [18]. The importance of high quality mineralised bone surrounding any hip prosthesis can have important implications. Some studies have postulated that sporting activity can have a positive effect in the bone–implant interface by encouraging bone growth [19]. Good bone stock in the femoral neck is of paramount importance in relation to hip resurfacing and future survivorship of the implant. So far there have been no femoral neck fractures in this cohort of patients. An incidence of 1.91% of femoral neck fracture following hip resurfacing has been reported with the mean time to fracture being 15 weeks [20]. This usually related to varus placement of the femoral component and intraoperative notching of the femoral neck. We believe that regular sporting activity following hip resurfacing will help maintain good bone stock of the femoral neck and potentially reduce the incidence of femoral neck fractures in the long term.

Conclusion

There may be concern that a return to sporting activity following hip resurfacing will lead to increased rates of wear, loosening and revision surgery. The majority of our patients in this study were reviewed at a relatively early stage following surgery as our key aim was to assess sporting activity following hip resurfacing. We plan to monitor this cohort of patients over the long-term to evaluate the incidence of detrimental effects from regular sporting activity. The potential complications of returning to sport following hip resurfacing must be balanced against the significant benefits of regular exercise on cardiovascular, metabolic and musculoskeletal systems. This study has shown that sporting activity can be maintained following hip resurfacing.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McGregory BJ, Stuart MJ, Sim FH. Participation in sports following knee and hip arthroplasty: Review of literature and survey of surgeon preferences. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:342–348. doi: 10.4065/70.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yun AG. Sports after total hip replacement. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(2):359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracey RB, McBride PPB. Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty. A minimum follow-up of five years. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2005;87(2):167–170. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B2.15030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black DL, Dalziel R, Young D, Shimmin A. Early results of Birmingham hip resurfacing. An independent study of the first 230 hips. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2007;89B:1431–1438. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.87b3.15556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naal FD, Maffiuletti NA, Munzinger U, Hersche O. Sports after hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(5):705–711. doi: 10.1177/0363546506296606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narvani AA, Tsiridis E, Nwaboku HC, Bajekal RA. Sports following Birmingham hip resurfacing. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27(6):505–507. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zahari C, Schmalzried T, Szuszczewicz E, Amstutz H. Assessing activity in joint replacement patients. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:890–895. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM, Leunig M. Which is the best activity rating scale for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(4):958–965. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0358-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1996;78:185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniel J, Pynsent PB, Mc Minn D (2004) Resurfacing of the hip under the age of 55 years with osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 86-B:177–84 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Collins DK. Cemented total hip replacements in patients who are less than 50 years old. J Bone Jt Surg [Am] 1984;66:357–359. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorr CD, Takei GK, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients less than 45 years old. J Bone Jt Surg [Am] 1983;65:474–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorr LD, Kane TJ, Conaty JP. Long-term results of cemented total hip arthroplasty in patients 45 years old or younger: a 16-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9:253–256. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Streicher RM, Semlitsch M, Schon R, Weber H, Rieker C. Metal on metal articulation for artificial hip joints: laboratory study and clinical results. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 1996;210:223–232. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1996_210_416_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowson D, Hardaker C, Flett M, Isaac GH. A hip joint simulator study of the performance of metal-on-metal joints. Part 1: the role of materials. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawley J, Metcalf JEP, Jones AH, et al. A tribological study of cobalt chromium molybdenum alloys used in metal-on-metal resurfacing hip arthroplasty. Wear. 2003;255:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1648(03)00046-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pescatello LS, Franklin BA, Fragard R, Farquhar WB, Kelly GA, Ray CA (2004) American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exercise 36(3):533–553 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Christian C. Osteoporosis: Diagnosis today and tomorrow. Bone. 1995;17(5 suppl):513S–516S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubs C, Gschwend N, Munzinger U. Sport after total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1983;101:161–169. doi: 10.1007/BF00436765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimmin AJ, Back D (2007) Femoral neck fractures following hip resurfacing. A national review of 50 cases. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 87-B: 463–4 [DOI] [PubMed]