Abstract

The quantification of sodium MR images from an arbitrary intensity scale into a bioscale fosters image interpretation in terms of the spatially-resolved biochemical process of sodium ion homeostasis. A methodology for quantifying tissue sodium concentration using a flexible twisted projection imaging sequence is proposed that allows for optimization of tradeoffs between readout time, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) efficiency and sensitivity to B0 susceptibility artifacts. The gradient amplitude supported by the slew rate at each k-space radius regularizes the readout gradient waveform design to avoid slew rate violation. Static field inhomogeneity artifacts are corrected using a frequency segmented conjugate phase reconstruction approach with field maps obtained quickly from co-registered proton imaging. High quality quantitative sodium images have been achieved in phantom and volunteer studies with real isotropic spatial resolution of 7.5×7.5×7.5 mm3 for the slow T2 component in ~8 minutes on a clinical 3T scanner. After correcting for coil sensitivity inhomogeneity and water fraction, the tissue sodium concentration in gray matter and white matter were measured to be 36.6±0.6 μmol/g wet weight and 27.6 ± 1.2 μmol/g wet weight, respectively.

Keywords: Sodium imaging, twisted projection imaging, quantitative imaging, tissue sodium concentration, ultra-short TE imaging

Introduction

Regulation of sodium homeostasis through counterbalancing low intracellular and high extracellular sodium ion concentrations with potassium ions is of vital importance for cellular function (1, 2). These ion gradients across the cell membrane provide the potential energy for many important cellular transport processes. Action potentials, intracellular pH regulation and many membrane transport processes are all directly dependent on the sodium ion gradient across the cell membrane. Damage to brain cell integrity and disruption of cell packing produce local increases in tissue sodium concentration (TSC) (3, 4). TSC, determined by quantitative MR imaging, has been shown to have a potential role in monitoring tissue viability in humans with diseases such as stroke and in monitoring treatment of brain tumors (3–6).

Despite these potential medical applications described more than two decades ago (7), quantitative sodium imaging has been slow to evolve. The sodium MR signal has a detection sensitivity of four orders of magnitude lower than that of the proton signal. It exhibits biexponential relaxation behavior with fast and slow transverse relaxation characteristics (T2fast ~1–3ms and T2slow ~12–25ms, respectively) in biological tissues (8). Therefore, sodium imaging requires an imaging sequence with a short excitation RF pulse and a short echo time (TE) to reduce signal loss from the rapid decay of the transverse magnetization.

Twisted projection imaging (TPI) is a 3D projection reconstruction sequence (3DPR) based approach that can achieve short TE values and high acquisition efficiency (9). When performed at long repetition times (TR) to allow full T1 relaxation, quantification of TSC is possible. However, the generation of TPI gradient waveforms is often limited by the hardware slew rate constraint, especially when starting twisting at low k-space radius is desired to reduce the number of projections needed to sample k-space at the Nyquist rate. Besides being potentially harmful to the subject and the gradient system, violations of the slew rate constraint can also cause uncertainty in the k-space trajectory. The slew rate constraint can be met by using low gradient amplitude or numerical smoothing. However, these approaches result in either a long readout time that ultimately limits the achievable spatial resolution due to T2 relaxation, or k-space trajectory deviations that degrade the point-spread-function (PSF) of the sequence. Meanwhile, the high data acquisition efficiency of TPI stems from its ability to sample more k-space locations in each repetition with a relatively long readout window. This renders TPI sensitive to static field (B0) inhomogeneity, even at the relatively low sodium resonance frequency. These B0 inhomogeneities must be corrected to avoid significant image blurring and distortion (10–14).

We propose an efficient approach to quantify TSC with a flexible TPI (flexTPI) sequence that uses the gradient hardware within its specifications. This sequence allows for shortening readout times without the need for numerical smoothing after waveform generation. The frequency-segmented conjugate phase reconstruction approach (10) is adopted to correct for B0 field inhomogeneity using field maps obtained from either co-registered proton or sodium images. High-quality quantitative sodium imaging is demonstrated in human brains with high spatial resolution within acceptable times on a clinical 3T scanner. The accuracy of TSC measurement is demonstrated in phantom studies. In vivo TSC measurements on the brain of multiple subjects are highly consistent and agree with those known values in tissues such as muscle and vitreous humor.

Materials and Methods

Tissue sodium concentration model

TSC measured with MRI is the water volume fraction weighted mean of the sodium concentrations in the three aqueous tissue compartments: the intracellular fluid (ICF), the interstitial fluid (ISF) and plasma. Sodium concentrations in plasma and ISF are similar, thus the ISF and plasma can be treated as one extracellular fluid (ECF) compartment. Due to the relatively small contribution of plasma to ECF volume in brain tissue (<3% blood volume fraction × 55% blood plasma volume fraction), the ECF volume is predominantly determined by the ISF, or extracellular space (ECS). Therefore,

| (1) |

where δ is the ECS volume fraction, w the tissue water volume fraction, and [Na+]ICF and [Na+]ISF are the ICF and ISF sodium concentrations, respectively. TSCm has dimensions of mmol/L wet tissue. If the tissue density, ρ, is known, TSC can be expressed in μmol/g wet tissue:

| (2) |

Values of w, δ and ρ have been measured in brain tissues (15–18). Values of δ generally range from 0.15 to 0.3 in normal adult brain tissue with a typical value of 0.2 (16). Typical values of other parameters in normal brain tissue are: w ~0.68 in white matter (WM) and ~0.83 in gray matter (GM) (15); [Na+]ICF ~ 12 mM; [Na+]ISF ~145 mM (2), and ρ ~1.04 g/ml (18). Using a δ value of 0.2, TSC can be estimated to be ~35.2 μmol/g wet tissue and ~ 33.4 μmol/g wet tissue in GM and WM, respectively. These values can be used as general guidelines for TSC measurements in vivo.

Alternatively, TSC values can be used to estimate δ as w can be measured with MRI (15):

| (3) |

Pulse sequence design

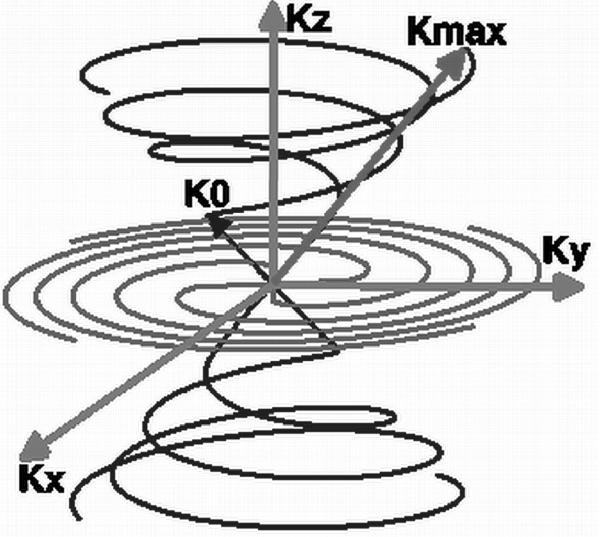

The TPI sequence samples k-space with trajectories distributed on a stack of evenly spaced concentric cones, as illustrated in Figure 1. Each k-space trajectory starts as a center-out radial line until it reaches a predefined k-space fraction (p) where t = t0 and k0 = pkmax. It then twists to maintain a constant sampling density with a fixed readout gradient strength G. The equations governing the twisting portion of the trajectories are [8]:

| (4) |

where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, θ (0 < θ < π) is the polar angle of the cone, φ(t) and φ0 (0 ≤ φ(t), φ0 < 2π) are the azimuthal angles at time t and time t0, respectively. The highest slew rate experienced by the trajectories is approximately:

| (5) |

with θ0 being the smallest polar angle of the cones. For a given Smax, the slew rate limited readout gradient amplitude is:

| (6) |

This value is often low, leading to a lengthy readout window.

Figure 1.

An illustration of k-space sampling strategy of TPI in which each trajectory has a radial component arising at the center of k-space and extending to K0 along a cone of angle θ, and then twisting along the surface of the cone to reach the maximum value Kmax. Each trajectory is rotated around the cone to fully sample its surface. Both positive and negative trajectories are acquired.

The flexTPI design allows the readout gradient amplitude g(t) to increase gradually at larger k-space radius as the slew rate constraint becomes less stringent. The design algorithm is provided with parameters such as: field of view (FOV), spatial resolution, acquisition bandwidth (BW), maximum slew rate allowed (Smax), radial fraction p and maximum readout gradient strength G desired. The actual maximum readout gradient amplitude Gmax value used is Gmax = min(BW /γFOV,G). The radial portion is designed to reach k0 rapidly; g(t0) = min(Gs(t0),Gmax) if possible. The twisted portion of the trajectory is governed by:

| (7) |

Constraints are imposed on the determination of g(t) to satisfy the slew rate as well as the maximum gradient constraints.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed scheme, gradient waveforms and the slew rates (calculated as square root of the sum of the squares of the slew rates on all three axes) experienced by the most slew rate demanding gradient waveforms for the original TPI and the flexible TPI sequences were simulated using MATLAB (Natick, MA, USA). These gradient waveforms were designed to image a FOV of 22 cm with a radial fraction of 0.2 to achieve 4.4 mm isotropic resolution. The maximum slew rate allowed was 15000 G/cm/s. Two sets of gradient waveforms were generated with the original TPI: one with the maximum slew rate supported gradient amplitude of 0.35 G/cm and the other with a higher gradient amplitude of 0.5 G/cm. An even higher readout gradient amplitude of 0.6 G/cm was used in the flexTPI waveform design.

Radiofrequency (RF) coils and B0 shimming

Single-tuned transmit/receive (T/R) birdcage coils with identical geometry and materials were designed for co-registered sodium/proton imaging. A customized head cradle was designed so that the RF coils could be switched without moving the head of subject. This twin RF coil configuration avoided the SNR loss that comes from a dual-tuned coil and allowed the shim values determined by the fast automatic linear shimming algorithm on the 1H signals to also be used for 23Na imaging (6, 19).

Gradient characterization

Timing errors between the requested and the actual start times of the gradients and analog-to-digital converter (ADC), as well as eddy currents induced by the time varying readout gradient can cause deviations of k-space trajectories from those prescribed, and consequently produce image distortion, especially for non-Cartesian sequences. The method proposed in (20) was adopted to measure the timing errors on the three physical axes. These measured timing error values were then used to align the start of the readout gradient waveforms to that of the ADC.

With proper gradient timing, eddy currents induced by the readout gradient were characterized to the first order on a spherical phantom (21). Because of their similarities in construction, the proton and the sodium RF coils have similar eddy current characteristics. This allowed eddy current correction data to be collected from the high SNR proton signals and used to reconstruct sodium images.

B0 field mapping

To correct for B0 inhomogeneity, three-dimensional B0 field maps were generated from pairs of either 23Na or 1H images acquired at two different TE values. With the sodium imaging approach, one extra dataset was collected without signal averaging with the same flexTPI sequence.

To reduce the total imaging time, the use of B0 field maps obtained from proton images to correct sodium imaging was tested with a 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo (SPGR) sequence. The TE values were chosen such that fat and water signals were in phase. A region-growing approach was used for three-dimensional phase unwrapping. The field maps were then used to correct sodium images by taking into account their frequency difference determined by the gyromagnetic ratios:

| (8) |

Image reconstruction

Image reconstruction used gridding with a Kaiser-Bessel kernel (22). Since k-space data collected at time t were evenly distributed on a sphere with radius k(t) in flexTPI, the density compensation factor used was simply:

| (9) |

where dk(t) is the local increment of k-space radius at k(t). The number of frequency segments N used was calculated from the maximum frequency range Δωmax with (11). To accelerate the reconstruction, gridding was performed in parallel for all frequency segments, thus the calculation of the gridding kernel was only performed once.

Quantification

Human brain and calibration phantom images with comparable coil loading were acquired under the same imaging conditions. The calibration phantom was used to derive the calibration curves of TSC as a function of signal intensity. This phantom consisted of three sealed cylindrical tubes (3 cm diameter) containing different sodium concentrations (30, 70, 110 mM), enclosed within a sphere (16 cm diameter) containing 60mM potassium chloride to match the electrical loading of a human head while minimizing the magnetic susceptibility effects from the cylindrical tubes. The tubes were made up in 3% agar to closely match T2 values to the in vivo tissue values.

To compensate for the spatial variation of the coil sensitivity, the double flip angle approach was used for B1 mapping (23). B1 inhomogeneity was then corrected by normalizing the signal intensities by r-α-sin(α) based on reciprocity (24), with α being the measured spatially dependent flip angle and r a scaling factor inversely proportional to the transmit power level to ensure the receive sensitivity was independent of transmit power. The low transmit power images were combined with the high transmit power images to improve SNR after coil sensitivity correction. Finally, the calibration curve was applied to obtain the TSC maps.

Although not necessary, either two vials attached to the inner surface of the 23Na RF coil or a small sphere placed in a holder centered near one end of the coil was present in both the calibration phantom scan and the subject scan. Either the vials or the small sphere could be used as alternative ways to normalize signal intensities between the two scans.

Accuracy of the TSC quantification in the phantom

The effect of B0 and B1 correction on the accuracy of the TSC measurement was validated using a high-resolution spherical phantom filled with 40 mM NaCl solution. As sodium has much longer T2 values in the free solution phantom (measured T2fast= T2slow ~60 ms) than in the calibration gel phantom (measured T2slow ~ 16 ms), the impact of T2 differences between sample and calibration on the quantification was demonstrated. To demonstrate the accuracy of the TSC measurement over the TSC range in brain tissues, another phantom containing seven vials with sodium concentrations ranging from 19.3 mM to 154 mM (19.3, 38.5, 57.8, 77.0, 115.5, 134.8, 154 mM) was also imaged and quantified. Both phantom experiments were repeated 3 three times to calculate the mean and standard deviation of the measurements.

Consistency of in vivo TSC measurement

The reproducibility of the TSC measurement in GM and WM was characterized by sequential imaging (n=5) of one healthy young male who remained stationary during the entire experiment. To characterize the consistency, repeated TSC measurements (n=5) in brain tissue were performed on multiple healthy young individual subjects (n=5, 4 males, 1 female, 23 – 45 years old). The subjects were removed from the scanner and RF coil between each imaging session to ensure the measurements were independent. Due to the length of these experiments, the entire data were collected in multiple sessions distributed over during a period of 6 weeks.

The proton images collected for B0 mapping were used as references to identify GM and WM. The TSC values in each imaging session were averaged values over a large number (n > 30) of voxels in the corresponding tissue types across the brain. For the consistency study, the intra-subject mean and the standard deviation were calculated for the TSC values in GM and WM from the five imaging sessions in each subject. These mean TSC values of each individual were then used to obtain the inter-subject mean and standard deviation of the TSC value for the group of five subjects. In the precision study, the means and the standard deviations were calculated for the TSC values in the five sequential imaging sessions.

To evaluate the accuracy of the TSC measurements in vivo, TSC values in vitreous humor and various muscle groups of the head (masseter, superficial temporalis, medial and lateral pterygoid muscles) were also measured. TSC measurement in vitreous humor was performed in the same manner as described above, while TSC in muscle was measured in one imaging session on one volunteer directed by high-resolution 1H images.

Tissue densities of 1.04 (18), 1.0 and 1.06 g/ml of tissue are used to convert the directly measured TSC (mmol/l of tissue) into μmol/g wet weight for brain tissues (gray matter and white matter), vitreous humor and muscle, respectively. ECS fraction values in GM and WM were estimated from measured TSC values using water fractions of 0.83 and 0.68 (15), respectively.

Experiment setup

All imaging was performed on a 3.0 Tesla clinical scanner (HDx Signa, GE Healthcare, Waukasha, WI) with multinuclear capabilities and a maximum slew rate of 15000 G/cm/s. Healthy adult human subjects were provided informed consent under an IRB approved protocol. The flexTPI sequence used for sodium imaging achieved a minimum TE of 0.36 ms with a constant 0.5 ms excitation RF pulse. Two signal averages were used to improve the SNR. The total scan time for each sodium data acquisition was approximately 8 minutes for all in vivo studies. The FOV and bandwidth used were 22 cm and 31.25 kHz, respectively.

The accuracy and consistency studies on the phantoms and humans used an equivalent readout matrix size of 44 × 44 × 44, giving a nominal isotropic spatial resolution of 5 mm. The readout length was ~12.3 ms with a radial fraction of 0.25 and a maximum gradient strength of 0.4 G/cm. A TR of 160 ms was used in the human study. In the accuracy studies on the phantoms, the TR was 250 ms to account for the longer sodium T1 in free solution. The experiment used to demonstrate the effectiveness of B0 correction in vivo used a higher nominal spatial resolution of 4.4 mm isotropic. With a radial fraction of 0.25 and maximum gradient amplitude of 0.2 G/cm, the readout time was longer at ~27.6 ms.

Automatic linear shimming on proton signals was employed and the shim values were carried over for the collection of B0 field mapping data as well as for sodium imaging. The additional acquisition for B0 field mapping with sodium images was performed with a TE of 2.36 ms. The B0 field maps from 1H images were obtained using 3D SPGR images acquired with TE values of 2.1 ms and 4.3 ms in less than one minute each. The reconstructed matrix size and resolution of these images were matched to the sodium images. Unless otherwise specified, sodium images were B0 inhomogeneity corrected with B0 maps from 1H imaging. Co-registered high-resolution 3D 1H SPGR images were also collected in one imaging session on one volunteer with a 3D isotropic spatial resolution of 1 mm to identify head muscle.

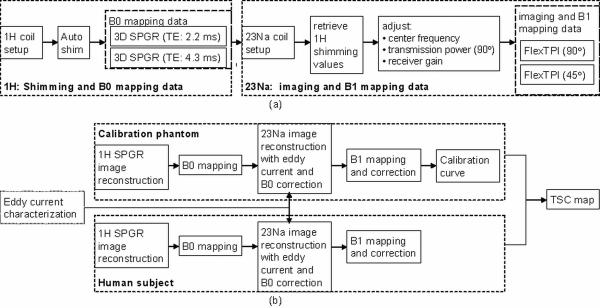

The complete data acquisition and quantification processes for a typical TSC measurement experiment are summarized and illustrated in Figures 2a and 2b, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Illustration of the data acquisition steps. (b) Flow chart of the image reconstruction and quantification processes. The eddy current correction data can be collected beforehand on 1H data, assuming the 1H and the 23Na coils have the same eddy current characteristics.

Results

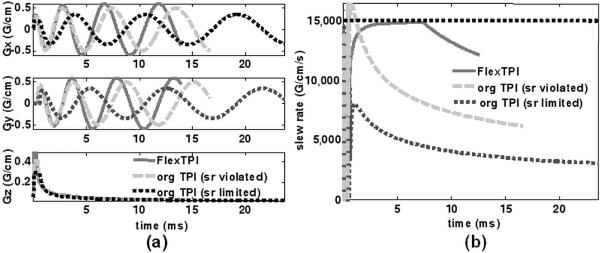

Gradient waveform design

The simulated typical gradient waveforms and the slew rates are shown in Figure 3. The readout windows of the original TPI sequence using gradient amplitude of 0.35 G/cm (dotted lines) and 0.5 G/cm (dashed lines) are about 25 ms and 17 ms, respectively, while that of the flexTPI sequence with gradient amplitude of 0.6 G/cm (solid lines) is shorter at around 13 ms as expected. The higher gradient amplitude used in the original TPI design caused a slew rate violation. In contrast, with even stronger maximum readout gradient, the flexTPI sequence achieved a shorter readout window within the system specifications.

Figure 3.

(a) Typical gradient waveforms designed with the flexTPI scheme (solid lines) and the original TPI scheme with readout gradient amplitude supported by the slew rate (dotted lines) and gradient amplitude higher than that supported by the slew rate (dashed lines). (b) Total slew rate curves corresponding to the waveform designs in (a). The horizontal line at 15,000G/cm/s denotes the maximum hardware slew rate.

Gradient characterization

Representative gradient waveforms of the flexTPI sequence and the corresponding measured k-space trajectory errors due to linear eddy currents and phase errors from B0 eddy currents are shown in Figures 4a, 4b and 4c, respectively. In this example, the k-space deviations on all three axes are closely correlated to the ideal k-space trajectories with less than 2% k-space interval deviation and less than 0.005 radian phase accumulated by B0 eddy currents.

Figure 4.

(a) Measured gradient waveforms for flexTPI on three axes during the acquisition time. (b) k-space deviation from the nominal trajectories due to linear eddy currents during the acquisition time. (c) Accumulated phase due to B0 eddy currents during the acquisition time. Representative axial images of a high-resolution phantom demonstrate the effects of deviations between the start of the ADC readout and the response of the gradient drivers producing the gradient waveforms: (d) timing error of 16 microseconds, (e) no timing error, and (f) no timing error and with eddy current correction.

The effect of gradient timing errors on the flexTPI images for a time delay of 16 μs between the start of the ADC and the onset of the gradient waveform on all three axes is shown in Figure 4d. The center of the image appears darker than the rim, and the high frequency signal features are emphasized. With the correct timing, more uniform signal intensity is achieved as shown in Figure 4e. The images reconstructed with and without eddy current correction (Figures 4e and 4f) show almost no perceptible impact on the image quality as the eddy current terms are small.

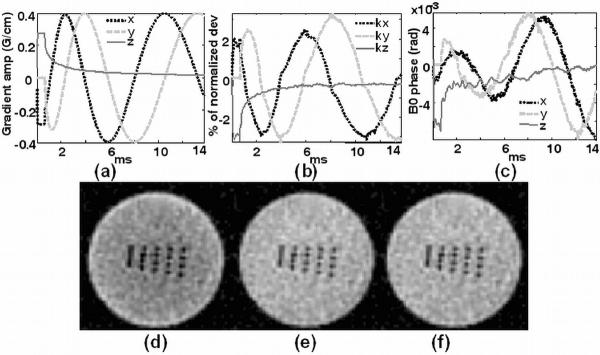

Accuracy

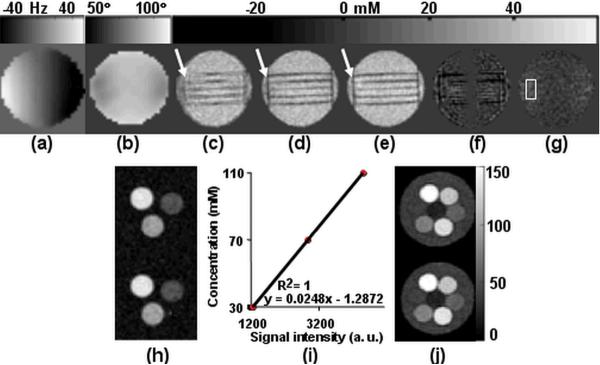

The effect of B0 and B1 correction on quantification accuracy of the TSC measurement is demonstrated in the coronal images of one representative slice of the high-resolution phantom in Figures 5a–g (the dark cylindrical rods are along the z-direction). Figure 5a shows the measured B0 field has a gradient along the z-direction, which spans a frequency range of −50 Hz to 50 Hz at sodium frequency. As shown in Figure 5b, the measured B1+ field is relatively homogeneous in the transverse plane but shows large falloff towards the end of the coil (~70° vs. ~90° in the center of the coil, the dark cylindrical rods are along the z-direction). Figure 5c–e show the quantified sodium concentration without correction, with only B0 correction and with both B0 and B1 correction, respectively. Image blurriness is seen near the rods in the phantom in Figure 5c (arrow). The blurriness is reduced when B0 correction is applied. The rods are much better defined as signal voids (Figure 5d). After both B0 and B1 inhomogeneity correction, Figure 5e shows more homogeneous sodium distribution that can be appreciated along the z-axis. The measured TSC is 40.6 ± 1.3 mM, in agreement with the known sodium concentration of the phantom (40.0 mM). Figure 5f shows the difference in sodium concentration with and without B0 correction, TSC difference is up to 30 mM. Figure 5g demonstrates the difference in mean TSC with and without B1 correction is ~7 mM in the region indicated by the white box.

Figure 5.

Representative coronal images showing the effectiveness of B0 and B1 field inhomogeneity correction. (a) B0 field maps in Hz show a gradient extending from ~−50 Hz to +50 Hz along the z-direction. (b) B1 maps show sensitivity falloff toward the end of the coil. (c) TSC maps without correction (d) TSC maps with B0 correction. (e) TSC maps with both B0 and B1 correction. (f) Difference images ((d) – (c)) showing the effectiveness of B0 inhomogeneity correction. (g) Difference images ((e) – (d)) showing the impact of B1 inhomogneity correction. The improvement in image quality can be clearly appreciated, as shown by the arrows and near the rods with B0 inhomogeneity correction. More homogeneous TSC has been obtained with B1 correction, especially along z-axis need the edges of the phantom. (h) Representative axial images of the calibration phantom containing three different sodium concentrations made in agar gel. (i) Linear calibration curve derived from the calibration phantom. (j) Representative axial images a phantom containing seven different vials filled NaCl solutions of concentrations range from 19.3 mM to 154 mM (19.3, 38.5, 57.8, 77.0, 115.5, 134.8, 154 mM). The acquisition time for sodium imaging was 13 minutes with a nominal isotropic resolution of 5 mm.

Two representative partitions of the calibration phantom are shown in Figure 5h. The derived calibration curve (Figure 5i) is linear with an intercept of less than 2 mmol/l. Representative sodium concentration maps of the phantom containing seven vials with different sodium concentrations are shown in Figure 5j. The measured sodium concentrations summarized in Table 1 are in agreement with the known sodium concentrations.

Table 1.

Measured and actual sodium concentration in a phantom experiment. The actual sodium concentrations diluted from a stock solution of 154.0 mM have an experimental error of 2%.

| Act. (mM) | 154.0 | 134.8 | 115.5 | 77.0 | 57.8 | 38.5 | 19.3 |

| Meas. (mM) | 155.2±1.5 | 133.0±1.3 | 117.6±1.1 | 77.1±0.5 | 56.9±0.6 | 38.7±0.7 | 18.6±0.8 |

B0 field inhomogeneity correction on human brain

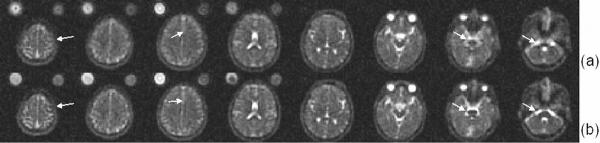

Representative human brain images with and without B0 field inhomogeneity correction are shown in Figure 6 from superior to inferior orientation. Severe field inhomogeneities from magnetic susceptibility effects are seen in the normalization vials as well as around the paranasal sinuses (Figure 6a). Correction of the B0 field inhomogeneity reduces, but does not completely remove, the image distortion in Figure 6b. Improvement in sharpness of the brainstem anatomy and improved SNR can also be readily appreciated in these images.

Figure 6.

Representative axial sodium images of a normal volunteer showing the effectiveness of B0 field inhomogeneity correction. (a) Uncorrected sodium images. (b) Corrected sodium images. The improvement in image quality can be appreciated in the brainstem and orbital frontal regions, as shown by the arrows. The acquisition time was 8 minutes with a nominal isotropic resolution of 4.4 mm.

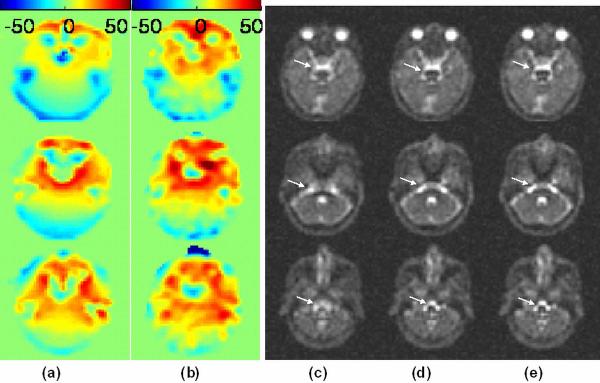

The comparison of using B0 field maps generated from both proton imaging and sodium imaging to correct for the sodium images is demonstrated in Figure 7, where three representative slices are shown. Figure 7a and 7b show the field maps obtained from sodium and proton imaging on the same scale, respectively. The general patterns of both field maps are similar, though some differences can be seen especially at low signal regions due to differences in actual resolution. Figure 7 (c–e) shows the images reconstructed from the same k-space data without correction, and corrected with B0 field maps obtained from sodium imaging and from proton imaging, respectively. Both corrected images demonstrate similar improvement in image sharpness and distortion reduction, as indicated by the arrows.

Figure 7.

Axial B0 field maps are shown for a normal volunteer using (a) sodium imaging in 4 minutes and (b) proton imaging in less than 2 minute. These B0 maps were applied to (c) the uncorrected images to derive (d) human images corrected using sodium B0 field maps and (e) human images corrected using proton B0 field maps. The improvements, appreciated in the brainstem (white arrows), are similar for both sodium and proton B0 maps.

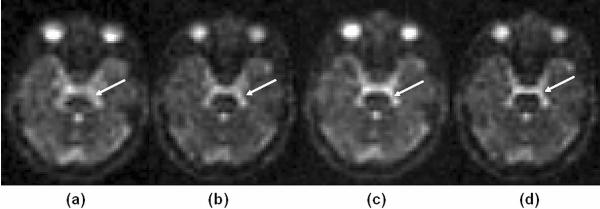

Effects of readout length

The images shown in Figure 8a and 8b were acquired with the flexTPI sequence with a readout length of 27.7 ms with and without B0 correction, while images in Figure 8c and 8d were collected with a readout length of 14.0 ms with and without B0 correction. All other parameters were identical except a higher gradient strength was used to achieve a shorter readout window. The shorter readout time with B0 correction (d) produces the least blurring of the brainstem (arrow), and shows better details of the brain anatomy.

Figure 8.

Axial sodium images acquired (a) with readout lengths of 28 ms (a) without B0 correction and (b) with B0 correction, and with readout length of 14 ms (c) without B0 correction and (d) with B0 correction. The shorter readout time with B0 correction (d) produces the least blurring of the brainstem (white arrow).

Consistency of in vivo TSC

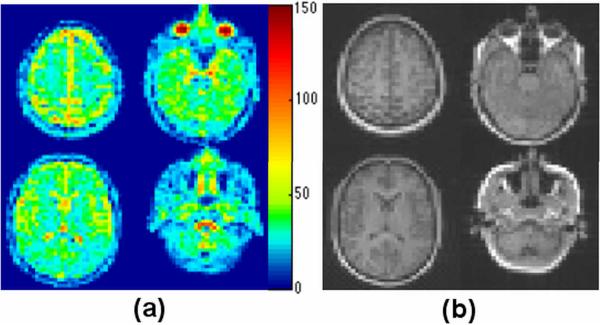

Representative sodium concentration maps obtained on a healthy volunteer are shown in Figure 9a. These maps are shown before compensating for tissue density and have the dimensional unit of mmol/L tissue. The corresponding T1-weighted proton images are also shown as anatomical reference (Figure 9b). The ocular globe and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) show the highest sodium concentrations colored from yellow to dark red. Some voxels have intermediate values due to the partial volume effect of averaging CSF and brain parenchyma. WM is predominately shown in light blue, while GM is recognized as green between CSF and white matter. In the reproducibility study, GM has a TSC of 37.2±0.5 μmol/g wet weight and WM has a TSC of 28.0±0.7 μmol/g wet weight. The TSC values for the consistency study are summarized in Table 2. GM has an average TSC value of 36.6 ± 0.6 μmol/g wet weight, while the WM has an average TSC value of and 27.6 ± 1.2 μmol/g wet weight. No significant differences were found between TSC values in the left and right hemispheres. Using Equation 3, the ECS volume fraction in GM and WM is calculated to be 0.20 and 0.15, respectively. The measured TSC value in vitreous humor is 133.6 ± 6.3 μmol/g wet weight, and that in the muscle is 26.2 ± 3.3 μmol/g wet weight. These values are in agreement with the values (131.8±3.8 mM in vitreous humor and 28.4 ± 3.6 μmol/g wet weight in skeletal muscle) reported in literature (25, 26). The TSC value measured in muscle is based on sampling multiple voxels across multiple muscle groups at the base of skull, and so shows larger variation. The larger variation of TSC in vitreous humor either reflects biological difference between subjects or can be due to the larger imaging distortion in the eyes (residual B0 effect, eye motion, etc.).

Figure 9.

Representative tissue sodium concentration maps (a) obtained on a healthy volunteer (unit: mmol/L tissue). The corresponding T1 weighted proton images are also shown (b) as anatomical references. The TSC images shown are before water fraction correction. The white matter is predominately shown in light blue, while the gray matter is recognized as green between CSF (shows as yellow to dark red due to partial volume effects with brain parenchyma) and white matter.

Table 2.

Average tissue sodium concentration (TSC) measured in individuals and for the group of five normal adult subjects (4 males, 1 female) where each participant under went five independent measurements. A tissue density of 1.04 g wet weight /mL was assumed in gray and white matter to compute tissue sodium concentrations in units of μmol/g wet weight of tissue from directly measured sodium concentrations in terms of mmol/L of wet tissue (shaded columns).

| Age (years) | White Matter (mmol/L tissue) | Gray Matter (mmol/L tissue) | White Matter (μmol/g wet weight) | Gray Matter (μmol/g wet weight) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1 | 35 | 29.6±0.6 | 38.3±0.7 | 28.5±0.6 | 36.8±0.7 |

| Subject 2 | 30 | 28.0±0.9 | 37.7±0.9 | 26.9±0.9 | 36.3±0.9 |

| Subject 3 | 22 | 30.3±0.7 | 38.8±0.9 | 29.1±0.7 | 37.3±0.9 |

| Subject 4 | 46 | 27.3±0.6 | 37.3±1.2 | 26.3±0.6 | 35.9±1.2 |

| Subject 5 | 29 | 28.1±0.4 | 38.2±0.7 | 27.0±0.4 | 36.7±0.7 |

| Average | 32.4±8.9 | 28.7±1.2 | 38.1±0.6 | 27.6±1.2 | 36.6±0.6 |

Discussion

The proposed flexible TPI design strategy allows k-space to be sampled efficiently without violating the gradient system constraints. Empirically, the constraints on g(t) in Eq. 7 are sufficient to satisfy the hardware constraints; the gradient amplitude at the locations of slew rate violation can be adjusted iteratively until the slew rate is satisfied if these constraints are inadequate. Further optimization can be potentially achieved by using the time-optimal gradient waveform design method recently proposed by Lustig et al. (27). The Cones sequence is a 3D sequence that samples k-space in a similar fashion but with a completely numerical gradient design to fully utilize the performance of the gradient system to traverse k-space more efficiently (28). The gradient waveforms in the flexTPI sequence are easier to calculate and are smoother, which may help to reduce eddy currents. As shown in Figure 4, eddy currents were minimal on our 3T scanner for a typical flexTPI acquisition, although eddy current correction was necessary for a 3DPR sequence used for proton imaging (29). In addition, calculating the k-space data density compensation factor in the flexTPI sequence is more straightforward.

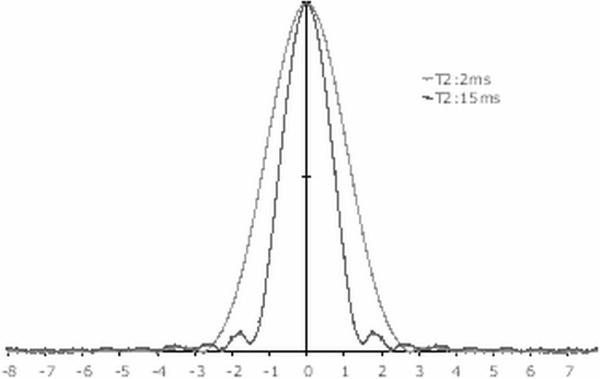

Despite the relatively narrower frequency range of the B0 field inhomogeneity for sodium imaging, as compared to 1H imaging at the same field strength, our results have shown that significant improvement in image quality can be achieved with appropriate correction. B0 field maps can be acquired from either sodium imaging or from fast proton imaging with appropriate co-registration. The need for this B0 correction is increasingly more important if longer readout times are employed to achieve a higher apparent SNR. However, a readout duration shorter than T2 is desired to avoid significant T2-blurring (30). This was verified in Figure 8 and the condition was satisfied in the precision and consistency studies for the long T2 component. Readout durations comparable to the short T2 value require significantly longer acquisition time to achieve a similar SNR and are impractical without increasing field strength. The PSF of the sequence with parameters used in the consistency study for T2 values of 15ms and 2ms are shown in Figure 10. The slow T2 component has a full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of ~1.5Δx (7.5 mm), with Δx being the nominal spatial resolution (5.0 mm), while the FWHM for the fast component is broader at ~2.4Δx (12.0 mm). The relative contribution of the fast and slow components to the measured TSC in each voxel depends on many acquisition parameters and the surrounding tissue properties. The impact of the PSF on TSC quantification in WM may be insignificant due to its relative uniformity across large regions. However, some partial-volume effects are expected in GM from WM and CSF, even when considering that the folded cortex has an effective thickness of twice the cortical thickness in young adults (31).

Figure 10.

Simulated point-spread-functions (PSF) for sodium imaging with flexTPI for two typical T2 values of 2ms and 15ms representing the fast and slow components, respectively. The acquisition parameters of the sequence used for the simulation are the same as those used in the consistency study. The PSFs are scaled to the same maximum peak amplitude. The fast component has a broader peak and, therefore, corresponds to a lower spatial resolution. The side lobes are due to zero padding used during the PSF generation.

The phantom quantification experiments produced less than a 4% error across the biologically meaningful sodium concentration range despite the large difference in the T2 properties of the calibration and standard phantoms. This result suggests that differences in T2 do not produce significant errors in TSC quantification. The shorter T2 of brain tissue compared to the calibration gel phantom may produce a slight underestimation in TSC. Nevertheless, consistent TSC values have been measured in a human head across repeated measurements on multiple healthy subjects. The TSC values measured in vitreous humor and muscle from the same experiments agree with the literature values. The TSC values in GM and WM are in agreement with those derived from independently measured sodium activity parameters using equation 1 and 2, and TSC values reported in human brain (4). TSC values measured using the 22Na dilution experiments in rats (49±6 mM) are also in agreement with our results after compensating for water content (32). Others have reported either lower (33) or higher (5) TSC values in normal brain tissue with sodium MRI. The difference is likely due to performance of different data acquisition and quantification schemes, as well as the difference in SNR and actual spatial resolution, instead of biological difference in different subjects according to our results. High TSC values of ~50–60 μmol/g wet tissue have also been reported with chemical approaches such as flame photometry or atomic absorption (34–36). For example, the TSC measured in (34) in rabbit cerebral cortex is 58.8 μmol/g wet weight Although the discrepancy between these values and the TSC values measured in human brain in vivo may be partly due to the biological sodium concentration difference and the tissue status at the time of the measurements (in vivo vs. ex vivo), the possibility also exists that our MR acquisition parameters are insensitive to part of the tissue sodium which has ultra short T2s (e.g. < 1ms) (37–40). Unfortunately, it is currently difficult to validate our TSC measurements in human brain tissues in vivo due to the invasive nature of the available independent chemical measurement approaches.

The current quantification scheme used separate calibration phantom scans, which doubled the data acquisition time. This was necessary to avoid the significant B0 inhomogeneity resulting from placing the calibration vials in the same imaging FOV as human head. Such distortions rendered the calibration curve generated from the vials unreliable. Short readout times (as were used in the accuracy and precision studies) and effective B0 inhomogeneity correction can minimize the distortion in the calibration vials to improve the efficacy of quantification.

Conclusion

The proposed flexible TPI sequence allows for efficient sampling of k-space within the system gradient hardware constraints. The effectiveness of using B0 maps obtained from 1H imaging to correct for B0 inhomogeneity artifacts in 23Na images with a frequency segmented conjugate phase reconstruction approach has been demonstrated. The high consistency and precision of the TSC measurement indicate that high quality quantitative sodium imaging can be performed on a clinical 3T scanner within an acceptable time.

Acknowledgements

Financial support is gratefully acknowledged from PHS grants RO1 NS386760, RO1 CA129553 and the Chicago Biomedical Consortium SPARK award.

References

- 1.Skou J. The influence of some cations on an adenosine triphosphatase from peripheral nerves. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1957;23:394–401. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lodish HF. Molecular cell biology. Scientific American Books; New York: 1999. p. 973. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thulborn KR, Davis D, Snyder J, Yonas H, Kassam A, Sodium MR. Imaging of Acute and Subacute Stroke for Assessment of Tissue Viability. Neuroimag Clin N Am. 2005;15:639–653. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thulborn KR, Gindin TS, Davis D, Erb P. Comprehensive MRI Protocol for Stroke Management: Tissue Sodium Concentration as a Measure of Tissue Viability in a Non-Human Primate Model and Clinical Studies. Radiology. 1999;139:26–34. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.1.r99se15156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldsmith M, Damadian R. NMR in cancer. Physiol Chem Phys. 1975;7:263–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouwerkerk R, Bleich KB, Gillen JS, Pomper MG, Bottlomley PA. Tissue sodium concentration in human brain tumors as measured with 23Na MR imaging. Radiology. 2003;227:529–537. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272020483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilal SK, Maudsley AA, Simon HE, Perman WH, bonn J, Mawad ME, Silver AJ, Ganti SR, Sane P, Chien IC. In vivo NMR imaging of tissue sodium in the intact cat before and after acute cerebral stroke. AJNR. 1983;4:245–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubbard PS. Nonexponential nuclear magnetic relaxation by quadrupole interactions. J Chem Phys. 53:985–987. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boada F, Gillen J, Shen G, Chang S, Thulborn K. Fast three dimensional sodium imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37:706–715. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noll DC, Meyer CH, Pauly JM, Nishimura DG, Macovski A. Deblurring for non-2D Fourier transform magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;25:319–333. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910250210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Man LC, Pauly JM, Macovski A. Multifrequency interpolation for fast off-resonance correction. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37:785–792. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schomberg H. Off-Resonance Correction of MR Images. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 1999;18:481–495. doi: 10.1109/42.781014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadah YM, Hu X. Algebraic reconstruction for magnetic resonance imaging under B0 inhomogeneity. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 1998;17:362–370. doi: 10.1109/42.712126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutton BP, Noll DC, Fessler JA. Fast, interative image reconstruction for MRI in the presence of field inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2003;22:178–188. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2002.808360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neeb H, Ermer V, Stocker T, Shah NJ. Fast quantitative mapping of absolute water content with full brain coverage. NeuroImage. 2008;42:1094–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sykova E, Nicholson C. Diffusion in Brain Excellular Space. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:1277–1340. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simonova Z, Svoboda J, Orkand P, Bernard CCA, Lassmann H, Sykova E. Changes of extracellular space volume and tortuosity in the spinal cord of Lewis rats with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Physiol Res. 1996;45:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Go KG. Physical and chemical methods for analysis of fluid compartments. In: Boulton AA, Baker GB, Walz W, editors. The neuronal microenvironment, Neuromethods. vol 9. Humana Press; Clifton, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ackerman JJH, Gadian DG, Radda GK, Wong GG. Observation of 1H NMR Signals with Receiver Coils Tuned for Other Nuclides. J Magn Reson. 1981;42:498–500. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeder SB, Faranesh AZ, Atalar E, McVeigh ER. A novel object-independent “balanced” reference scan for echo-planar imaging. JMRI. 1999;9:847–852. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199906)9:6<847::aid-jmri13>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu A, Daniel BL, Pauly JM, Butts Pauly K. Improved Slice Selection with Eddy Current Compensation for R2* Mapping during Cryoablation. J Magn Reson Imag. 2008;28:190–198. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson JI, Meyer CH, Nishimura DG, Macovski A. Selection of a Convolution Function for Fourier Inversion Using Gridding. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 1991;10:473–478. doi: 10.1109/42.97598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Insko EK, Bolinger L. Mapping of the Radiofrequency Field. J Magn recon. 1993;103:82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoult DI. The principle of reciprocity in signal strength calculations – a mathematical guide. Concepts Magn Reson. 2000;12:173–187. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh D, Prashad R, Sharma SK, Pandey AN. Double logarithmic, linear relationship between postmortem vitreous sodium/potassium electrolytes concentration ratio and time since death in subjects of chandigrarh zone of northwest India. Journal of Indian Academy of Forensic Medicine. 2005;27:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Constantinides CD, Gillen JS, Boada FE, Pomper MG, Bottomley PA. Human skeletal muscle: sodium MR imaging and quantification-potential applications in exercise and disease. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:1144–51. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.2.r00jl46559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lustig M, Kim SJ, Pauly JM. A Fast Method for Designing Time-Optimal Gradient Waveforms for Arbitrary k-Space Trajectories. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2008 doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.922699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurney PT, Hargreaves BA, Nishimura DG. Design and Analysis of a Practical 3D Cones Trajecory. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:575–582. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu A, Brodsky E, Grist TM, Block WF. Rapid fat-suppressed isotropic steady-state free precession imaging using true 3D multiple-half-echo projection reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:692–699. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuethe DO, Adolphi NL, Fukishima E. Short Data-Acquisition Times Improve Projection Images of Lung Tissue. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:1058–1064. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. PNAS 2000 USA. 97:11050–11055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christensen JD, Barrere BJ, boada FE, Vevea M, Thulborn KR. Quantitative tissue sodium concentration mapping of normal rat brain. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:83–89. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madelin G, Oesingmann N, Nielles-Vallespin S, Herbert J, Johnson G, Inglese M. 3T sodium MRI of patients with multiple sclerosis. In proceeding of 16th annual meeting of ISMRM; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 2008. p. 511. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanig RC, Aprison MH. Determination of Calcium, Copper, Iron, Magnesium, Manganese, Potassium, Sodium, Zinc and Chloride concentrations in several brain areas. Analytical biochemistry. 1967;21:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(67)90178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder WS, Cook MJ, Karhausen LR, Nasset ES, Howells GP, Tipton IH. Report of the task group on reference man. Pergamon; Oxford: 1984. p. 411. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikkilineni SR, Rousseau JE, Hall RC, Frier HI, Eaton HD. Sodium and potassium concentration of brain and dura mater in chronic hypovitaminosis A of calves. J Dairy Sci. 56:395–398. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(73)85184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee CO, Fozzard HA. Activities of potassium and sodium ions in rabbit heart muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1975;65:695–708. doi: 10.1085/jgp.65.6.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta RK, Gupta P, Moore RD. NMR studies of intracellular metal inos in intact cells and tissues. Ann Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1984;13:221–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.13.060184.001253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rooney WD, Springer CS. A comprehensive approach to the analysis and interpretation of the resonances of spins 3/2 from living systems. NMR Biomed. 1991;4:209–226. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940040502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nissen H, Jacobsen JP, Horder M. Assessment of the NMR visibility of intraerythrocytic sodium by flame photometric and ion-competitive studies. Magn Reson Med. 1989;10:388–398. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910100310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]