Abstract

Background

The liver contains macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells (mDC) that are critical for the regulation of hepatic inflammation. Most hepatic macrophages and mDC are derived from monocytes recruited from blood via poorly understood interactions with hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells (HSEC). Human CD16+ monocytes are believed to contain the precursor populations for tissue macrophages and mDC.

Results

We report that CD16+ cells localize to areas of active inflammation and fibrosis in chronic inflammatory liver disease and that a unique combination of cell surface receptors promotes the transendothelial migration of CD16+ monocytes through human HSEC under physiological flow. CX3CR1 activation was the dominant pertussis-sensitive mechanism controlling transendothelial migration under flow and expression of the CX3CR1 ligand CX3CL1 is increased on hepatic sinusoids in chronic inflammatory liver disease. Exposure of CD16+ monocytes to immobilized purified CX3CL1 triggered β1 integrin-mediated adhesion to VCAM-1 and induced the development of a migratory phenotype. Following transmigration or exposure to soluble CX3CL1, CD16+ monocytes rapidly but transiently lost expression of CX3CR1. Adhesion and transmigration across HSEC under flow was also dependent on vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) on the HSEC.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that CD16+ monocytes are recruited by a combination of adhesive signals involving VAP-1 and CX3CR1 mediated integrin-activation. Thus a novel combination of surface molecules, including VAP-1 and CX3CL1 promotes the recruitment of CD16+ monocytes to the liver allowing them to localize at sites of chronic inflammation and fibrosis.

Introduction

The liver contains bone-marrow derived myeloid DCs (mDC) and macrophages (Kupffer cells) that are recruited from blood via the hepatic sinusoids. They act as immune sentinels to detect and coordinate responses to invading pathogens and antigens entering the liver via the portal vein1–3. Under basal conditions these cells are replenished by recruitment of precursors from blood and this increases with inflammation. The exact nature of the precursor cells is unclear but they are likely to reside within the circulating CD16+ monocyte population4–7.

mDC arise from bone marrow-derived progenitors within the monocyte pool8–10 and several populations of precursors have been proposed including lineage negative CD11c+ monocytes, CD34+ progenitors11 and in humans CD16+ monocytes12. Human monocytes display heterogeneity defined by expression of chemokine receptors, adhesion molecules, CD14 and CD1613–15. The CD14+CD16++ subset expresses high levels of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 and is believed to give rise to DCs with potent antigen-presenting capabilities16 and inflammatory tissue macrophages15, 17. Furthermore, transendothelial migration of CD16+ monocytes in vitro induces differentiation into functional DCs suggesting that recruitment itself may shape their subsequent differentiation18.

Integral to mDC function is the capacity to traffic from one anatomical compartment to another. In the liver this involves a pathway that traverses the space of Disse and takes the cells along the hepatic sinusoids to the portal tract lymphatics19–21. The recruitment of precursor mDC from the blood into tissues across endothelium is poorly understood22. In the mouse, precursor mDC enter inflamed skin using ICAM-2, P-Selectin and E-Selectin and the chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR2 and CCR523 but little is known about hepatic recruitment via the sinusoidal vascular bed. Because recruitment of neutrophils and lymphocytes to the liver involves distinct adhesion pathways24, 25 we hypothesised that unique combinations of molecules might regulate monocyte recruitment. We report that recruitment of human CD16+ monocytes to the inflamed liver involves unique combinations of adhesion molecules in which interactions mediated by VAP-1 and the chemokine CX3CL1 are critically important.

Materials and Methods

Tissue and Blood

Liver tissue was obtained from livers removed at transplantation at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital from patients with alcoholic liver disease (n=6); primary biliary cirrhosis (n=6); primary sclerosing cholangitis (n=6) and autoimmune hepatitis (n=6). Peripheral blood was obtained from healthy volunteers and liver transplant recipients. Samples were collected after informed consent following local Ethics Committee approval.

Antibodies and Reagents

Soluble CX3CL1 and all anti-chemokine receptor mAbs except anti-CX3CR1 were obtained from R&D Systems Europe and used at recommended concentrations (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Antibody Target | Clone | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CD14 | UCHM1 | Serotec |

|

CD16 (FACS) CD16 (IHC) |

3G8 DJ130c |

Serotec Dako |

| CD29 | 12G10 | Serotec |

| CD31 | M0823 | Dako |

| CD56 | MEM-188 | Serotec |

| CD62L | FMC46 | Serotec |

| CD86 | FUN-1 | BD Biosciences |

| CX3CL1 | 51637 | R & D Systems |

| CX3CR1 | 2A9-1 | MBL (Woburn, USA) |

| Ep-CAM | HEA-125 | Progen Biotec |

| HLA-DR | L243 | BD Biosciences |

| ICAM-1 | 11C81 | R&D Systems |

| VAP-1 | TK8-14 | Kind gift of Dr David Smith, Biotie Therapeutics |

| VCAM-1 | 4B2 | R&D Systems |

Immunohistochemistry

6µm cryostat sections were air-dried on poly-L-lysine treated slides, acetone-fixed (10min) and stained. Sections were pre-incubated with 2.5% horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) in TBS prior to mouse anti-human mAb against CD16 or CX3CL1 in TBS/0.1%NHS. Control sections were incubated with isotype-matched control mAb. Antibody binding was assessed using ImmPress peroxidise visualisation with Novared chromogen (Vector Laboratories). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 30mg of human liver using RNEasy (Qiagen, UK) after DNAse treatment with RNAse free DNAse (Qiagen). 50ug extracted RNA was transcribed into cDNA using iScript cDNA (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and eluted RNA and cDNA measured (NanoDrop, Thermo-Fisher Scientific). Expression of human CX3CL1 mRNA was quantified using Taqman Fluorogenic 5’-nuclease assays and gene-specific 5’FAM-labeled probes on an ABI Prism 7900 detector. Threshold cycle (Ct) values of the target gene were normalized to GAPDH and differential expression levels calculated using 2−ΔΔCt.

Flow Cytometry

Blood mononuclear cells isolated using Lympholyte (Cedarlane Laboratories, Burlington, Canada) were resuspended in labelling medium (PBS/0.5%FCS/0.1mM EDTA). Fc receptors were blocked with 10ug/ml mouse immunoglobulin (10min). Directly conjugated mAb were added for 20min and cells resuspended in labelling medium and analyzed using a CyAn flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Bucks, UK). Cells were maintained on ice throughout except for the demonstration of CX3CR1 internalisation which was performed at 37°C.

Isolation of CD16+ Monocytes

OptiPrep density gradient centrifugation 26 produced 75–85% pure monocytes and CD16+ monocytes were then isolated from the enriched population by high-speed flow cytometric sorting. Fc receptors on the enriched monocytes were blocked with normal mouse Ig. Directly conjugated mAb against CD16 and CD56 added on ice for 20 min before washing and resuspending in labelling medium and sorted using a MoFlo cell sorter (Beckman-Coulter). Three gates were set during the sort: one to exclude doublet events, one to include monocytes and exclude other cells/debris, and one to include only CD16+CD56− cells. This produced a population of >98% pure CD16+ monocytes.

Isolation and Culture of Human Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells (HSEC)

HSEC were isolated using published methods with the substitution of NycoDenz (Axis Shield) for the discontinued metrizamide for density-gradient centrifugation)27. Fresh liver was minced and incubated with collagenase IV (Sigma, Poole, UK) for 30 min at 37°C before filtering through 40µm nylon mesh, diluted in PBS and layered on 25% Nycodenz/PBS and centrifuged at 700g for 20min. Cells at the interface were collected, washed and cholangiocytes removed by negative immunomagnetic selection with anti-HEA-125. Endothelial cells were positively selected using anti-CD31 antibody and cultured in human endothelial basal media plus penicillin/streptomycin/L-glutamine/10% human serum, HGF and VEGF (10 ng/mL, Peprotech, UK) and used within four passages. This protocol was developed to isolate sufficient cells from either normal or diseased human liver for use in functional assays. In rats it has been suggested that CD31 should not be used to isolate sinusoidal cells because cell-surface CD31 is absent from quiescent sinusoidal endothelium and its use generates cells with low frequencies of fenestrae28. However we find that human sinusoidal endothelial cells express cell surface CD31, albeit at lower levels than vascular endothelium, a finding consistent with other published reports29. To confirm that CD31-selected cells from human liver have a sinusoidal phenotype we demonstrated expression of several receptors that are present on sinusoidal but not vascular endothelium including the hyaluronan receptor LYVE-130, the C-type lectins L-SIGN31, L-SECtin, mannose receptor and CLEVER-125, 32, 33. These cells thus have a unique sinusoidal phenotype. They also express ICAM-1 and VAP-1 and increase expression of VCAM-1 in response to cytokines, a phenotype that corresponds to activated sinusoidal endothelium in vivo. Consistent with their distinct phenotype we have previously reported functional and signalling responses in these cells that differ from those seen with vascular endothelial cells27, 34. The relevance of in vitro studies using HSEC to the situation in vivo is illustrated by the fact that many of our in vitro findings with HSEC have subsequently been confirmed by others using in vivo models. For example the involvement of VAP-1 in lymphocyte recruitment via hepatic sinusoids was first proposed using HSEC in vitro27 and subsequently confirmed by others using rat and mouse models in vivo35, 36. Thus HSEC cultured for up to 4 passages maintain expression of cell surface receptors that a) define them as sinusoidal in origin and b) allow them to interact with leukocytes during flow-based assays. We thus believe that these cells, despite losing fenestrations during passage in culture, are appropriate to model leukocyte recruitment to the liver particularly as this process usually occurs through damaged or inflamed sinusoids and we refer to them as human liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (HSEC).

Flow-based Adhesion Assays

Flow-based adhesion assays were conducted as described37. HSEC were grown to confluence in glass capillaries for 24hr, stimulated for 24hr with TNFα (10ng/mL, R&D Systems) and connected to the flow-based system. In some experiments, soluble proteins were coated onto the slides; recombinant CX3CL1 (500 ng/mL, R&D Systems), recombinant VAP-1 (1µg/mL, gift from David Smith, Biotie Therapies), recombinant VCAM-1 (5µg/mL, R&D Systems) or human albumin (1%, Sigma, Poole, UK ). CD16+ monocytes were perfused through the capillaries at wall shear stresses that mimic flow through hepatic sinusoids (0.05 Pa). Adherent cells were visualized under phase-contrast microscopy and rolling, adherent (phase bright) and transmigrated cells (phase dark) quantified by offline digital analysis. The number of adherent cells was calculated/mm2/106cells perfused. Adhesion was blocked using anti-VCAM-1 (BBIG-V1), anti-ICAM-1 (BBIG-I1, R&D Systems), anti-CX3CR1 (2A9-1, MBL, MA) anti-VAP-1 (TK8-14, gift of David Smith, Biotie Therapies) and pertussis toxin (PTX) (Sigma, UK). Blocking reagents incubated with HSEC or monocytes for 30 minutes and washed out before assay.

Transwell Assay

Falcon transwells (24 wells/plate, 5µm pore, Becton-Dickinson) coated on the upper membrane surface with 20% rat-tail collagen, were seeded with 5×104 HSEC, grown to confluence for 24hr and stimulated with TNFα (10ng/mL) for a further 24hr. 5×105 CD16+ monocytes were added to top chamber for 1.5 hours before rinsing the top well to remove non-adherent cells. After 24hr transmigrated cells were harvested from the bottom well, washed in PBS/BSA and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Isolation and Characterization of Liver mDC

Hepatic mDC were isolated from freshly explanted liver using mechanical and density gradient separation as described7. Hepatic mDC were identified by flow cytometry as cells within the monocyte cloud that expressed CD86 and high levels of HLA-DR.

Activation of β1 integrin by occupancy of CX3CR1

CX3CR1 was engaged using purified recombinant CX3CL1. VLA-4 activation by 2mM MnCl2 was used as a positive control. 12G10 antibody that recognizes a conformation dependent CD29 epitope was used to detect activated VLA-438. Incubation with primary mAb or isotype-matched control was done for 45 min (room temperature) during CX3CR1 engagement. FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rat) was used to detect 12G10 binding by flow cytometry.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post test with GraphPad InStat (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Phenotype of CD16+ Monocytes

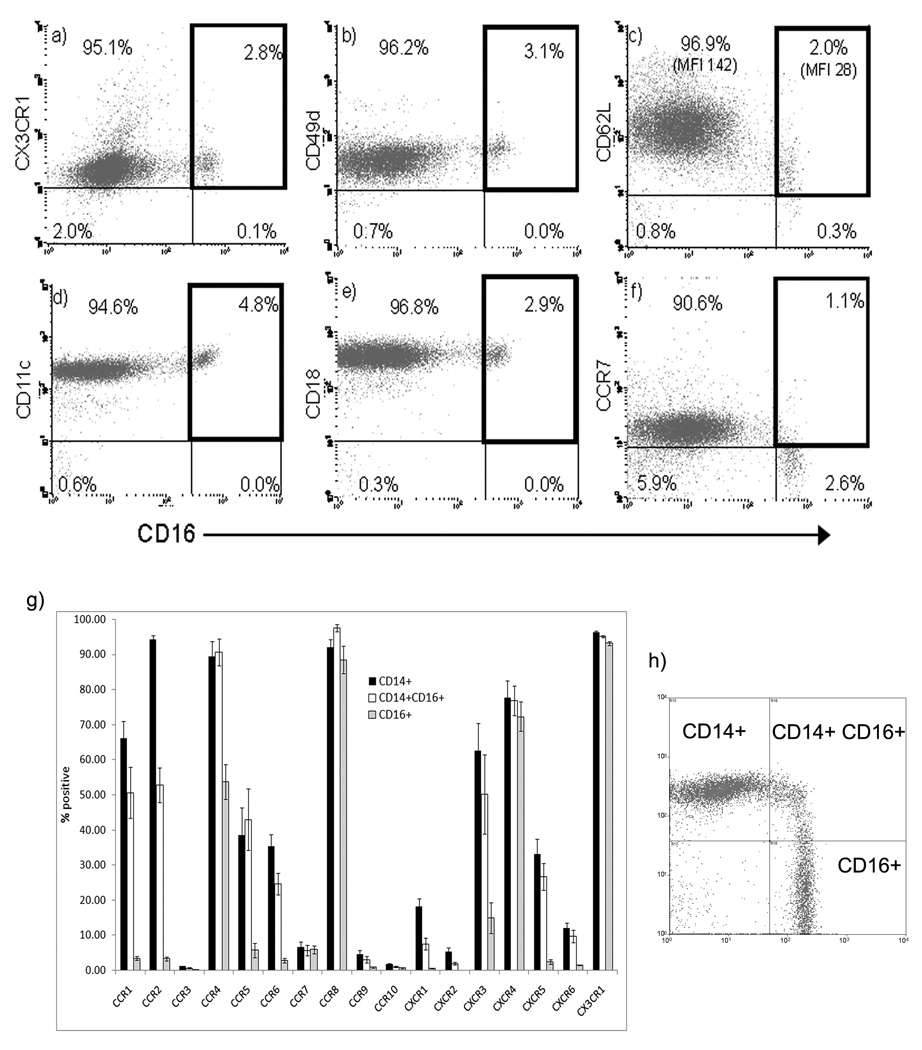

We detected three subsets of monocytes from human blood CD16+CD14−; CD16+CD14+ and CD14+CD16− (figure 1). CD16+ monocytes from human blood expressed low levels of two molecules associated with lymph node entry CD62L and CCR7. The chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR2, CCR4, CCR5, CCR6, CXCR1, CXCR3 and CXCR5 were expressed on more CD14+ than CD16+ cells. The CD16+ CD14− subset had the most limited chemokine receptor repertoire with CD14+ cells having a more inflammatory phenotype. CCR8, CXCR4 and CX3CR1 were expressed at similar levels on all three subsets.

Figure 1.

CD16+ and CD16− monocytes were analyzed for the expression of cell adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors. Some surface molecules, such as CX3CR1, CD49d and CD18 were expressed at the same level on both populations (a, b, e). When compared to CD16− monocytes, molecules such as CD62L and CCR7 were expressed at a lower level or not at all on CD16+ monocytes (c, f). CD11c was noted on both populations, but at a slightly higher level on CD16+ monocytes (d), consistent with their putative role as mDC precursors. The complete characterization of chemokine receptor expression on three populations of monocytes (h) defined by expression of CD14 and CD16 as CD14+CD16+, CD14−CD16+ and CD14+CD16− is shown in (g). The plots in (a–f) are representative profiles. The mean ± SEM of five experiments is shown in (g).

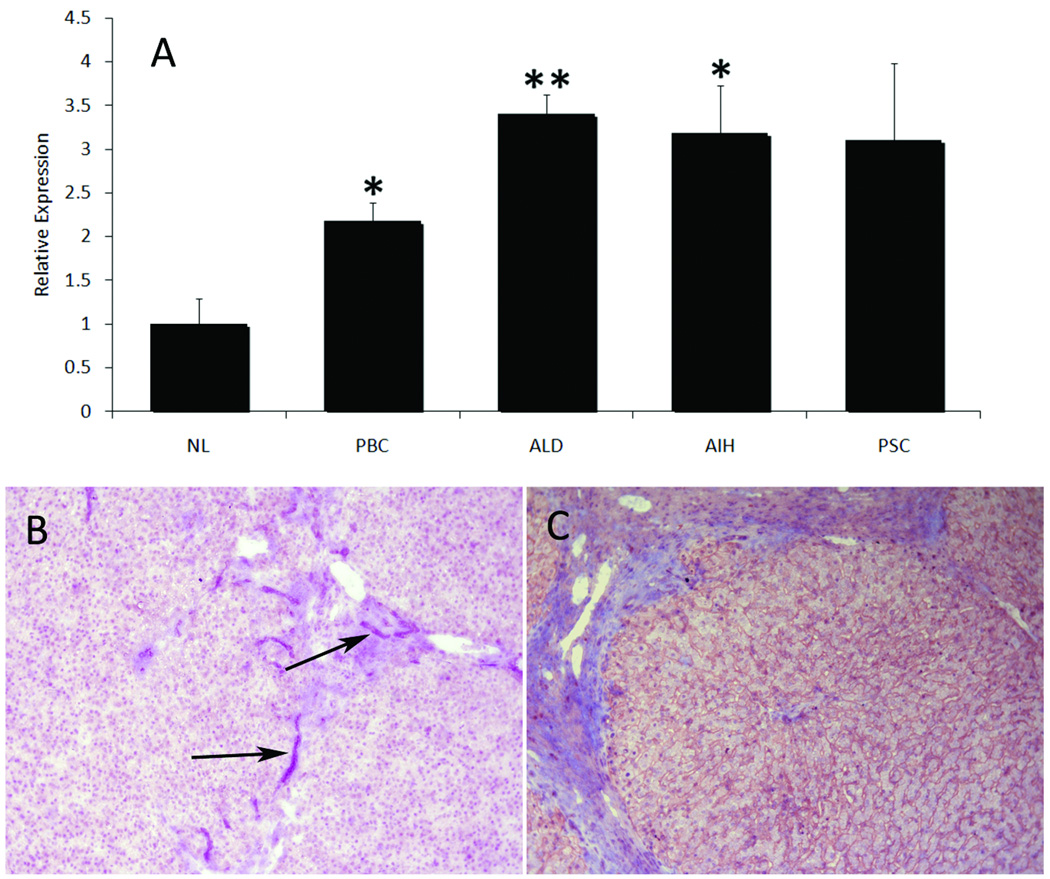

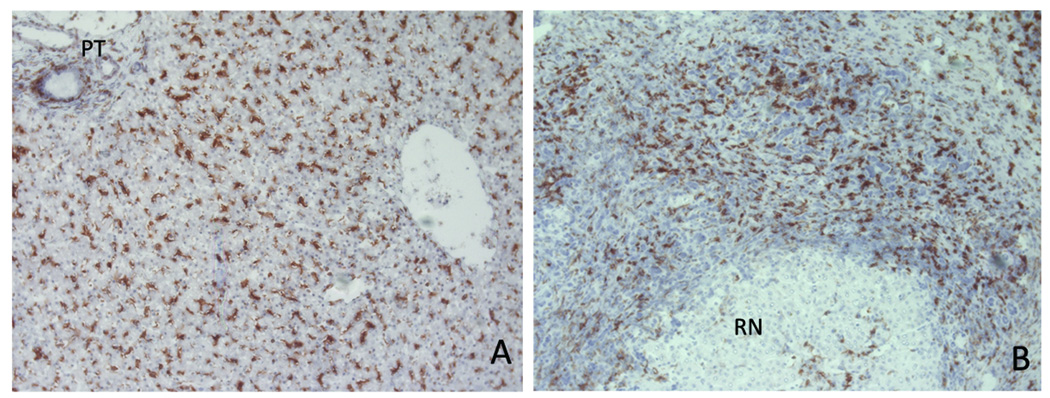

Localization of CX3CL1 and CD16+ cells in human liver

CX3CL1 in normal human liver was largely limited to bile ducts whereas in diseased liver it was also detected on sinusoids (Fig 2). Increased expression in inflammatory disease was confirmed by real-time qPCR (Fig 2c). In normal liver CD16+ cells were detected throughout the parenchyma consistent with kupffer cells and on mononuclear cells within portal tracts. In diseased liver CD16+ cells were increased at areas of inflammation including fibrotic septa and expanded portal tracts where they were seen in close association with bile ducts. In cirrhotic liver there was a relative loss of CD16+ cells within regenerative nodules associated with increased numbers at sites of inflammation/fibrosis (Fig 3).

Figure 2.

Normal and diseased human liver tissue was analysed for the expression of CX3CL1. (A) Total RNA was analysed for the expression of CX3CL1 mRNA by qPCR demonstrating a 2-fold increase in primary biliary cirrhosis and a 3–3.5-fold increase in alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) compared with non-inflamed liver. A similar increase was detected in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), though this did not reach significance. All values were relative to normal liver (NL) (n = 6 ± SEM, p ≤ 0.01 *, p ≤ 0.001 **). Immunohistochemical analysis of normal liver (B) revealed expression of CX3CL1 was limited to biliary structures (arrowed), whilst in diseased liver expression persisted on bile ducts and increased on sinusoids (C).

Figure 3.

The localization of CD16+ cells was assessed in normal and diseased human liver tissue by immunohistochemistry. In normal liver (A), CD16+ cells were located throughout the parenchyma and portal tracts (PT) but in diseased liver (B) were associated with the inflammatory infiltrate and fibrotic septa and largely absent from regenerative nodules (RN).

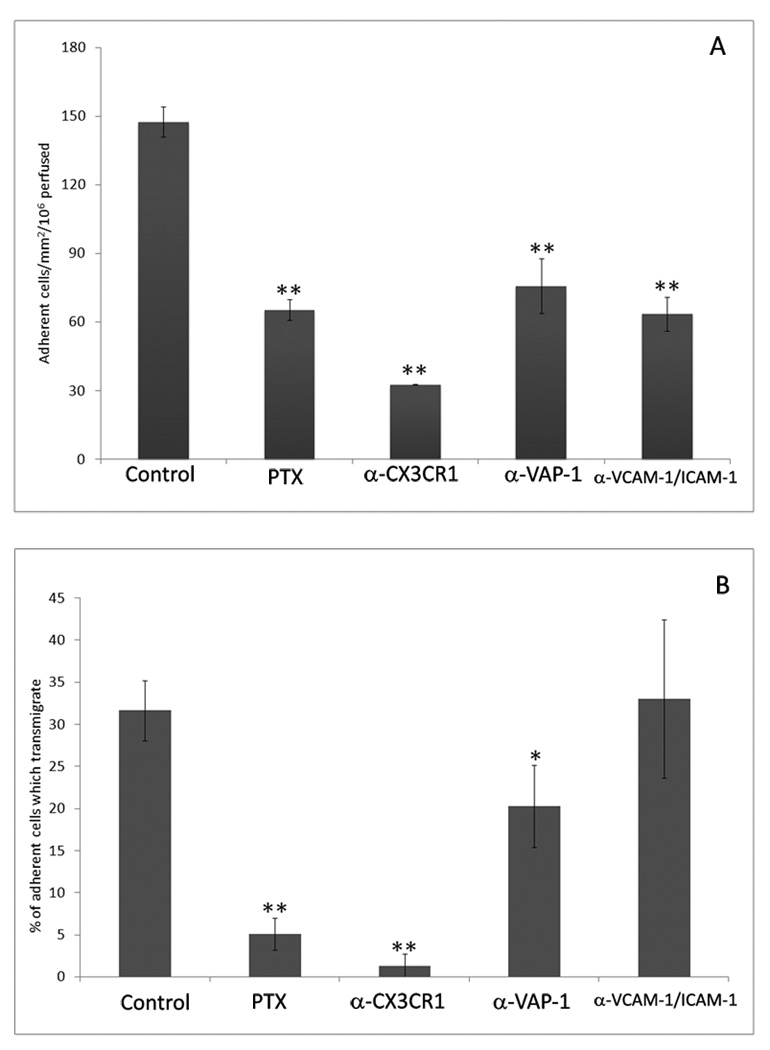

Adhesion under conditions that mimic physiological flow through liver sinusoids

CD16+ monocytes purified from peripheral blood as described above were perfused through microslides containing confluent HSEC stimulated with TNFα for 24hr. The number of CD16+ monocytes binding HSEC was determined (Fig 4a) and adhesion subclassified into cells which became activated, changed shape and migrated across the endothelial monolayer (phase dark, Fig 4b). Several inhibitors had no effect on adhesion or migration on HSEC, including antibodies against P- and E- selectin (data not shown) confirming the lack of involvement of selectins in this vascular bed39. Heterotrimeric Gαi proteins are involved in chemokine receptor signalling and can be inhibited using PTX. Pre-incubation of CD16+ monocytes with PTX caused a decrease in total adherent cells and virtually abolished transmigration as demonstrated by the lack of phase-dark, monocytes beneath the endothelium in figure 4b. Because CD16+ cells express high levels of CX3CR1 we looked to inhibit this receptor using antibodies and by desensitisation by prior exposure to ligand CX3CL1. Both approaches reduced transmigration (normalised to number of adherent cells) to a similar level seen with PTX treatment (Fig 4b) suggesting that CX3CR1 is the dominant GPC receptor involved. Total adhesion was more efficiently inhibited by anti-CX3CR1 antibody than by PTX suggesting that some adhesion is GPC-independent consistent with previous studies showing that transmembrane CX3CL1 can support leucocyte adhesion directly (Fig 4a). Antibodies against VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in combination or VAP-1 decreased total adherent cells (Fig 4a) whereas anti-ICAM-1 or anti-VCAM-1 alone had no effect (data not shown). Inhibition of HSEC with anti-VAP-1 antibodies immediately before and during the flow-based adhesion assay reduced the proportion of cells undergoing transendothelial migration (Fig 4b).

Figure 4.

CD16+ monocytes adhere to and transmigrate across HSEC under flow. Pre-treatment of CD16+ monocytes with PTX or HSEC with blocking antibodies to VAP-1, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 or CX3CL1 resulted in a significant decrease in the total number of cells adhering to the endothelial monolayer from flow (a). We quantified the number of adherent cells that subsequently went on to transmigrate through the HSEC monolayer. Transmigrated cells that have migrated beneath the endothelial monolayer were phase dark and easily distinguished from the phase bright cells adherent on surface of the monolayer. The numbers of adherent cells transmigrating was significantly reduced in the presence of a blocking anti-VAP-1 antibody and virtually abolished by the treatment of HSEC with anti-CX3CL1 or of CD16+ monocytes by pertussis toxin (b). In contrast blocking antibodies to VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 prevented adhesion, but not the transmigration of CD16+ monocytes (b). Blocking antibodies to E-Selectin and P-Selectin on HSEC did not affect adhesion or transmigration of CD16+ monocytes (not shown), consistent with previous findings that selectins have no role in adhesion in low flow state of liver sinusoids. n = 5 ± p ≤ 0.01 *, p ≤ 0.001 **. HSEC were confirmed to be CD31, L-SIGN, LYVE-1 and VAP-1+ as reported previously27, 30, 31.

Adhesion under flow to soluble CX3CL1 and VCAM-1

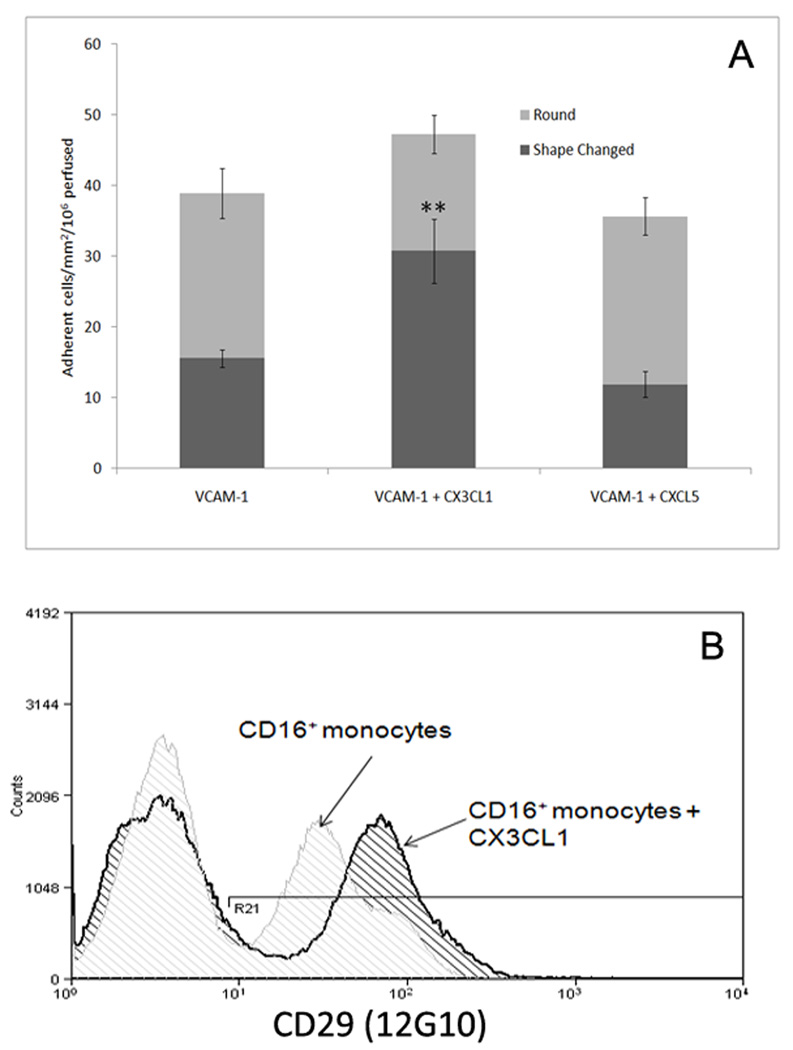

To further investigate the roles of CX3CL1 and VCAM-1 adhesion and migration under flow were studied with combinations of purified proteins. Microslides were coated with soluble CX3CL1 and VCAM-1. VCAM-1 but not CX3CL1 alone (data not shown), was able to support CD16+ monocytes adhesion; of the adherent cells approximately 40% changed shape and developed a migratory phenotype. When VCAM-1 was co-immobilised with CX3CL1 the total number of adherent cells increased and the proportion undergoing shape-change increased to 70% (Fig 5a). No change was seen in the level of adhesion or shape-change on VCAM-1 when an irrelevant chemokine was co-immobilised with VCAM-1. This adhesion and shape-change was associated with activation of the VLA-4 integrin (Fig 5b) as demonstrated by increased binding of mAb 12G10, which recognises the conformation-dependent active site on VLA-440, following exposure of CD16+ monocytes to soluble CX3CL1. Thus the engagement of CX3CR1 by immobilized CX3CL1 induces downstream activation of integrins.

Figure 5.

CX3CL1 treatment induces adhesion and shape change in CD16+ monocytes on VCAM-1. CD16+ monocytes bound to immobilised VCAM-1 in microslides. Less than 50% of the cells undergo shape change. The combination of immobilised VCAM-1 and CX3CL1 supported a higher number of adherent cells the majority of which showed morphological changes consistent with a migratory phenotype. Furthermore, analysis of the activation of the α4β1 integrin on CD16+ monocytes demonstrated a near doubling of median channel fluorescence following exposure to CX3CL1 (b). Flow data represent the mean ± SEM of three experiments, cytometry data representative of three repeats. p ≤ 0.001 **

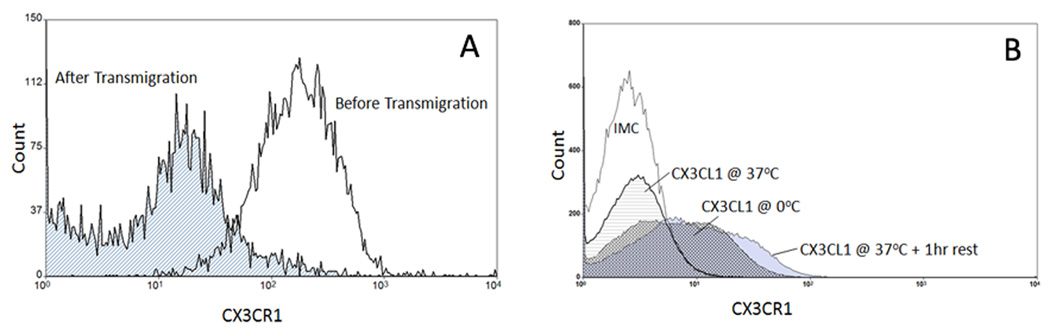

CX3CR1 is downregulated after transmigration across HSEC

The expression of CX3CR1 on CD16+ monocytes following transmigration was studied in transwells in which HSEC were cultured on membrane inserts and CD16+ monocytes applied to the top chamber. Cells that migrated were removed from the bottom chamber and levels of CX3CR1 determined. Following transmigration through HSEC, the expression of CX3CR1 decreased on CD16+ monocytes (Figure 6) and pre-incubation of CD16+ monocytes with soluble CX3CL1 reduced surface CX3CR1 which was re-expressed one hour after removal of soluble CX3CL1. This was not due to receptor masking as expression remained detectable if the experiment was repeated at 0°C (Fig 6b).

Figure 6.

A comparison of CX3CR1 expression on CD16+ monocytes prior to and after transmigration across HSEC in vitro. Purified CD16+ monocytes were applied to the top chamber of a transwell coated with HSEC that had been stimulated with TNFα. Transmigrated cells were collected and compared to pre-emigrant cells for CX3CR1 expression. The transmigrated cells exhibited a near-complete loss of CX3CR1 expression (a). Additionally, this loss of expression could be recapitulated by incubating CD16+ monocytes with CX3CL1 prior to antibody labelling (b). Pre-incubation for 1hr completely diminished receptor expression which recovered following an additional 1hr rest following removal of exogenous CX3CL1. We confirmed this was not due to receptor masking by repeating the experiment on ice. This receptor loss following engagement of CX3CR1 may contribute to retaining precursor DC in the liver promoting their maturation into liver-specific mDC. Representative flow cytometric profiles from three replicate experiments.

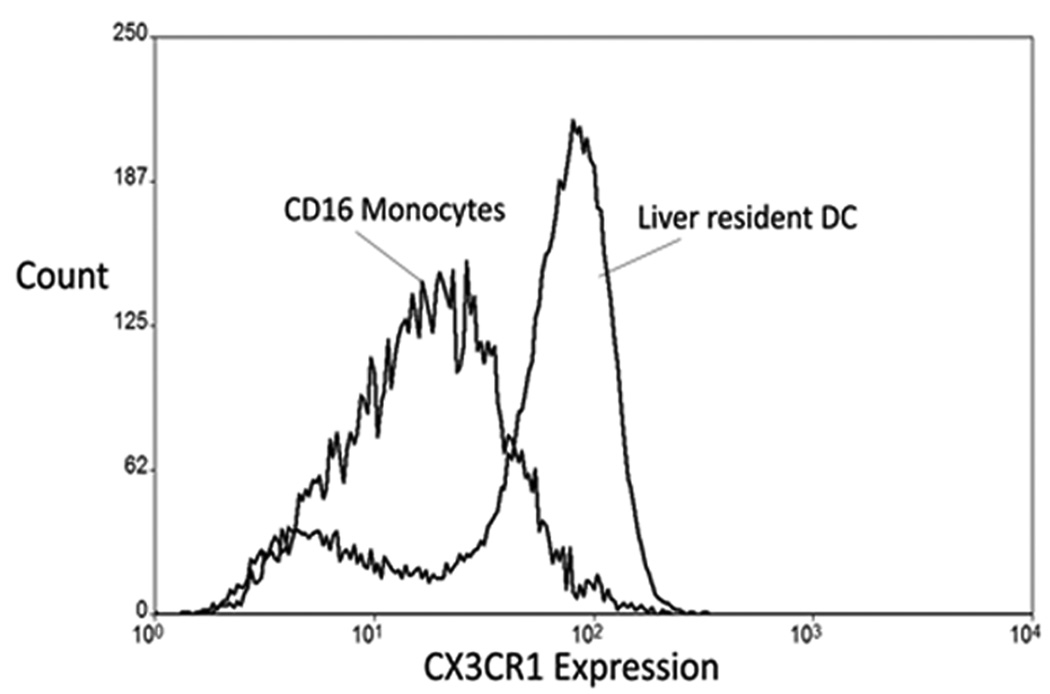

Expression of CX3CR1 on intrahepatic CD16+ cells

Matched blood and liver tissue from patients undergoing liver transplantation was used to compare expression of CX3CR1 on mDC freshly isolated from liver tissue with CD16+ monocytes from the same patient’s blood. Figure 7 demonstrates the intermediate level of CX3CR1 on CD16+ monocytes in blood wheras hepatic mDC defined by expression of CD86 and MHC Class II show heterogeneous CX3CR1 expression with some cells expressing high levels whereas others have levels comparable to those seen in blood CD16+ monocytes.

Figure 7.

A comparison of the expression of CX3CR1 on CD16+ monocytes and mDC from human liver. Peripheral blood CD16+ monocytes taken from a patient about to undergo liver transplantation for end stage liver disease exhibited an intermediate level of expression of CX3CR1, similar to the level of expression noted in healthy donors (Fig 1a). The mDC, representing mature forms of DC precursors that transmigrated across HSEC, were isolated from the liver of the same patient a few hours later and identified by flow cytometry as cells within the monocyte cloud that expressed CD86 and high levels of MHC Class II. The mDC exhibited either high or low expression of CX3CR1 and when compared to the intermediate level of expression on CD16+ monocytes, suggesting that the microenvironment of the liver may regulate the expression of CX3CR1. Representative flow cytometric profiles from three replicate experiments.

Discussion

The liver contains mDCs and tissue macrophages that regulate local immune responses. Under basal conditions these cells are continually replenished by the recruitment of precursors from blood and this increases with inflammation. We show that CD16+ cells redistribute in the chronically inflamed liver and can be detected at sites of inflammation and fibrosis (Fig 3). This is consistent with studies suggesting that CD16+ cells are the precursors of inflammatory tissue macrophages and inflammatory DCs13. Human CD16+ cells undergo differentiation into DCs after migration through endothelium10, 16, 18 and CD16+ DCs are present in the human liver41 leading us to investigate the molecules involved in CD16+ monocyte recruitment from blood into the liver via hepatic sinusoids. We used flow-based adhesion assays incorporating primary human hepatic sinusoidal endothelium to model the liver sinusoid27. We showed that human CD16+ monocytes express a cell adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors that could promote recruitment from blood, including CCR4, CXCR4, CX3CR1, CD18 and CD49d. We then demonstrated that they use a combination of CX3CL1, VCAM-1 and VAP-1 to arrest on HSEC from flow and a combination of CX3CR1 and VAP-1 to undergo transendothelial migration. Thus we show for the first time that VAP-1 is involved in DC precursor recruitment to peripheral tissue and define the role played by CX3CR1 in transmigration through human endothelium under flow.

CX3CR1, which is expressed at uniformly high levels on CD16+ monocytes (Fig 1), was the dominant chemokine receptor involved (Fig 4–5) and antibodies against CX3CR1 inhibited both adhesion and transmigration across HSEC. CX3CL1 is a transmembrane chemokine that can support adhesion independently of signalling through its GPC receptor consistent with our finding that adhesion of CD16+ cells on HSEC is more efficiently inhibited by anti-CX3CL1 antibodies than PTX. However transmigration was clearly dependent on signalling via CX3CR1 because it was almost completely prevented by PTX. To investigate the role of CX3CL1 further we studied adhesion under flow to recombinant proteins. In this system CX3CL1 was unable to support adhesion on its own but facilitated adhesion when co-immobilised with VCAM-1 by activating the α4β1 integrin. The recombinant CX3CL1 used in these experiments is not fully glycosylated and because GPC-independent adhesion is mediated by the mucin domains that decorate transmembrane CX3CL1 this may explain its inability to directly support adhesion.

CX3CL1 has previously been shown to support monocyte adhesion to HUVEC under flow17 and our observations extend its role to a liver-specific vascular bed and implicate it in transendothelial migration in addition to adhesion. CX3CL1 is expressed in human liver and in the present study we confirm expression on bile ducts and show induced expression in chronic inflammatory liver disease on sinusoids where it could act to promote recruitment of CX3CR1+ cells from blood (Fig 2)42, 43. CD16+ monocytes in blood showed homogenous intermediate levels of CX3CR1 whereas mDC isolated from the liver included CX3CR1high cells and a population that expressed levels comparable to blood CD16+ monocytes. CD16+ monocytes lost CX3CR1 surface expression during the process of transmigration and as a consequence of receptor engagement by CX3CL1. Exposure to soluble CX3CL1 in vitro resulted in a profound but transient loss of cell-surface CX3CR1 and could explain why prior exposure to soluble CX3CL1 prevents transendothelial migration; a similar effect has been reported for other chemokine receptors44. Thus CX3CL1 must be appropriately retained and presented on endothelium to function efficiently. The re-expression of CX3CR1 after cells have been recruited to the liver parenchyma could be important for their onward migration to areas of portal or lobular inflammation where CX3CL1 is also strongly expressed (figure 242).

In addition to CX3CL1 and VCAM-1 VAP-1 was involved in CD16+ monocyte transendothelial migration under flow. VAP-1 belongs to an expanding family of ectoenzymes involved in cellular trafficking45. VAP-1 is present on liver sinusoidal endothelium where it has been implicated in lymphocyte recruitment in humans and rodents27, 35, 36. Soluble VAP-1 is detected at high levels in the serum of patients with chronic liver disease but not other inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis46, 47. VAP-1 can mediate sialic acid dependent tethering and transendothelial migration of lymphocytes on sinusoidal endothelium27, 48. This is the first time that VAP-1 has been implicated in monocyte transendothelial migration although reduced monocyte recruitment to inflammatory sites has been reported in mice after VAP-1 blockade49. We found that VAP-1 was involved in both adhesion and transendothelial migration. The combination of immobilised CX3CL1 and VAP-1 proteins on their own failed to support significant levels of adhesion suggesting that VAP-1 operates in conjunction with other receptors to mediate transendothelial migration consistent with data showing that enzymatic activity of VAP-1 modulates the expression of other adhesion molecules34 (Fig 5). These findings add to an evolving body of literature that implicates VAP-1 as an important molecule in leucocyte transmigration across hepatic sinusoidal endothelium in vitro and in vivo and provide further evidence that the sinusoidal bed uses distinct combinations of molecules to recruit leucocytes to the liver parenchyma25, 34–36, 50. The role of VAP-1 in transendothelial migration is particularly interesting. Monocyte transendothelial migration across other endothelium involves CD31, CD99, CD226 and the JAMs which are present at tight junctions22, 51–53 the lack of which in hepatic sinusoids could explain why VAP-1 has a dominant role in this vascular bed.

The recruitment of monocytes to the liver is a major factor in determining the outcome of hepatic inflammation. Inflammatory monocytes drive liver injury and fibrosis54; myeloid DCs play critical roles in regulating immune responses to injury and infection and M2 macrophages are central to the resolution of hepatic inflammation and scarring1, 4, 55. The demonstration that VAP-1 and CX3CL1 are implicated in the recruitment of CD16+ monocytes across inflamed hepatic endothelium and that CD16+ cells localize at areas of inflammation and fibrosis has important implications for the pathogenesis of hepatic inflammation and the design of therapies to modulate monocyte recruitment in liver disease. The recent appreciation that VAP-1 can be inhibited by small molecule enzyme inhibitors opens up exciting therapeutic approaches to target this receptor. It is thus critical to understand which leucocytes rely on VAP-1 for entry into tissue and the outcome of inhibiting this receptor in vivo27, 56, 57.

Acknowledgements

Studies were funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant: 5RO1AA014257 ); the Medical Research Council (17026 and 4164); CRUK and the Wellcome Trust. Dr Aspinall was supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Association for Study of the Liver and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. We are grateful to our clinical colleagues and patient donors for provision of blood and tissue samples.

Footnotes

Author contributions: AA and SMC did the lab work with help from MB, EL and RA; CJW assisted with the design of the VAP-1 studies; AA wrote the first draft with DHA; CJW and PFL helped with flow based adhesion assays; DHA supervised the work.

References

- 1.Klein I, Cornejo JC, Polakos NK, John B, Wuensch SA, Topham DJ, Pierce RH, Crispe IN. Functional properties of bone marrow derived and sessile hepatic macrophages. Blood. 2007;110:4077–4085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lian ZX, Okada T, He XS, Kita H, Liu YJ, Ansari AA, Kikuchi K, Ikehara S, Gershwin ME. Heterogeneity of dendritic cells in the mouse liver. J Immunol. 2003;170:2323–2330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abe M, Zahorchak AF, Colvin BL, Thomson AW. Migratory responses of murine hepatic myeloid, lymphoid-related, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells to CC chemokines. Transplantation. 2004;78:762–765. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000130450.61215.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau AH, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells and immune regulation in the liver. Gut. 2003;52:307–314. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kusano F, Tanaka Y, Marumo F, Sato C. Expression of C-C chemokines is associated with portal and periportal inflammation in the liver of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Lab Invest. 2000;80:415–422. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosma BM, Metselaar HJ, Mancham S, Boor PP, Kusters JG, Kazemier G, Tilanus HW, Kuipers EJ, Kwekkeboom J. Characterization of human liver dendritic cells in liver grafts and perfusates. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:384–393. doi: 10.1002/lt.20659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai WK, Curbishley SM, Goddard S, Alabraba E, Shaw J, Youster J, McKeating J, Adams DH. Hepatitis C is associated with perturbation of intrahepatic myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cell function. J Hepatol. 2007;47:338–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naik SH, Metcalf D, van NA, Wicks I, Wu L, O'Keeffe M, Shortman K. Intrasplenic steady-state dendritic cell precursors that are distinct from monocytes. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:663–671. doi: 10.1038/ni1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tacke F, Randolph GJ. Migratory fate and differentiation of blood monocyte subsets. Immunobiology. 2006;211:609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginhoux F, Tacke F, Angeli V, Bogunovic M, Loubeau M, Dai XM, Stanley ER, Randolph GJ, Merad M. Langerhans cells arise from monocytes in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:265–273. doi: 10.1038/ni1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenzwajg M, Canque B, Gluckman JC. Human dendritic cell differentiation pathway from CD34+ hematopoietic precursor cells. Blood. 1996;87:535–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randolph GJ, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Liebman RM, Schakel K. The CD16(+) (FcgammaRIII(+)) subset of human monocytes preferentially becomes migratory dendritic cells in a model tissue setting. J Exp Med. 2002;196:517–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Fingerle G, Strobel M, Schraut W, Stelter F, Schutt C, Passlick B, Pforte A. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes exhibits features of tissue macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2053–2058. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grage-Griebenow E, Zawatzky R, Kahlert H, Brade L, Flad H, Ernst M. Identification of a novel dendritic cell-like subset of CD64(+) / CD16(+) blood monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:48–56. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200101)31:1<48::aid-immu48>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ancuta P, Rao R, Moses A, Mehle A, Shaw SK, Luscinskas FW, Gabuzda D. Fractalkine preferentially mediates arrest and migration of CD16+ monocytes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1701–1707. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randolph GJ, Beaulieu S, Lebecque S, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science. 1998;282:480–483. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudo S, Matsuno K, Ezaki T, Ogawa M. A novel migration pathway for rat dendritic cells from the blood: hepatic sinusoids-lymph translocation. J Exp Med. 1997;185:777–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuno K, Ezaki T. Dendritic cell dynamics in the liver and hepatic lymph. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;197:83–136. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(00)97003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuno K, Nomiyama H, Yoneyama H, Uwatoku R. Kupffer cell-mediated recruitment of dendritic cells to the liver crucial for a host defense. Dev Immunol. 2002;9:143–149. doi: 10.1080/1044667031000137610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imhof BA, urrand-Lions M. Adhesion mechanisms regulating the migration of monocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:432–444. doi: 10.1038/nri1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pendl GG, Robert C, Steinert M, Thanos R, Eytner R, Borges E, Wild MK, Lowe JB, Fuhlbrigge RC, Kupper TS, Vestweber D, Grabbe S. Immature mouse dendritic cells enter inflamed tissue, a process that requires E- and P-selectin, but not P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1. Blood. 2002;99:946–956. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee WY, Kubes P. Leukocyte adhesion in the liver: distinct adhesion paradigm from other organs. J Hepatol. 2008;48:504–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shetty S, Lalor PF, Adams DH. Lymphocyte recruitment to the liver: Molecular insights into the pathogenesis of liver injury and hepatitis. Toxicology. 2008;254:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graziani-Bowering GM, Graham JM, Filion LG. A quick, easy and inexpensive method for the isolation of human peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol Methods. 1997;207:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lalor PF, Edwards S, McNab G, Salmi M, Jalkanen S, Adams DH. Vascular adhesion protein-1 mediates adhesion and transmigration of lymphocytes on human hepatic endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:983–992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeLeve LD, Wang X, McCuskey MK, Mccuskey RS. Rat liver endothelial cells isolated by anti-CD31 immunomagnetic separation lack fenestrae and sieve plates. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G1187–G1189. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00229.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neubauer K, Lindhorst A, Tron K, Ramadori G, Saile B. Decrease of PECAM-1-gene-expression induced by proinflammatory cytokines IFN-gamma and IFN-alpha is reversed by TGF-beta in sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatic mononuclear phagocytes. BMC Physiol. 2008;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prevo R, Banerji S, Ni J, Jackson DG. Rapid plasma membrane-endosomal trafficking of the lymph node sinus and high endothelial venule scavenger receptor/homing receptor stabilin-1 (FEEL-1/CLEVER-1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52580–52592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai WK, Sun PJ, Zhang J, Jennings A, Lalor PF, Hubscher S, McKeating JA, Adams DH. Expression of DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR on Human Sinusoidal Endothelium: A Role for Capturing Hepatitis C Virus Particles. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:200–208. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gramberg T, Soilleux E, Fisch T, Lalor PF, Hofmann H, Wheeldon S, Cotterill A, Wegele A, Winkler T, Adams DH, Pohlmann S. Interactions of LSECtin and DC-SIGN/DC-SIGNR with viral ligands: Differential pH dependence, internalization and virion binding. Virology. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gramberg T, Hofmann H, Moller P, Lalor PF, Marzi A, Geier M, Krumbiegel M, Winkler T, Kirchhoff F, Adams DH, Becker S, Munch J, Pohlmann S. LSECtin interacts with filovirus glycoproteins and the spike protein of SARS coronavirus. Virology. 2005;340:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalor PF, Sun PJ, Weston CJ, Martin-Santos A, Wakelam MJ, Adams DH. Activation of vascular adhesion protein-1 on liver endothelium results in an NF-kappaB-dependent increase in lymphocyte adhesion. Hepatology. 2007;45:465–474. doi: 10.1002/hep.21497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonder CS, Norman MU, Swain MG, Zbytnuik LD, Yamanouchi J, Santamaria P, Ajuebor M, Salmi M, Jalkanen S, Kubes P. Rules of recruitment for Th1 and th2 lymphocytes in inflamed liver: a role for alpha-4 integrin and vascular adhesion protein-1. Immunity. 2005;23:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martelius T, Salaspuro V, Salmi M, Krogerus L, HOCKERSTEDT K, Jalkanen S, Lautenschlager I. Blockade of vascular adhesion protein-1 inhibits lymphocyte infiltration in rat liver allograft rejection. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1993–2001. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curbishley SM, Eksteen B, Gladue RP, Lalor P, Adams DH. CXCR3 Activation Promotes Lymphocyte Transendothelial Migration across Human Hepatic Endothelium under Fluid Flow. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:887–899. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mould AP, Garratt AN, Askari JA, Akiyama SK, Humphries MJ. Identification of a novel anti-integrin monoclonal antibody that recognises a ligand-induced binding site epitope on the beta 1 subunit. FEBS Lett. 1995;363:118–122. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00301-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong J, Johnston B, Lee SS, Bullard DC, Smith CW, Beaudet AL, Kubes P, et al. A minimal role for selectins in the recruitment of leukocytes into the inflamed liver microvasculature. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2782–2790. doi: 10.1172/JCI119468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newham P, Craig SE, Clark K, Mould AP, Humphries MJ. Analysis of ligand-induced and ligand-attenuated epitopes on the leukocyte integrin alpha4beta1. J Immunol. 1998;160:4508–4517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bamboat ZM, Stableford JA, Plitas G, Burt BM, Nguyen HM, Welles AP, Gonen M, Young JW, DeMatteo RP. Human liver dendritic cells promote T cell hyporesponsiveness. J Immunol. 2009;182:1901–1911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Efsen E, Grappone C, Defranco RM, Milani S, Romanelli RG, Bonacchi A, Caligiuri A, Failli P, Annunziato F, Pagliai G, Pinzani M, Laffi G, Gentilini P, Marra F. Up-regulated expression of fractalkine and its receptor CX3CR1 during liver injury in humans. J Hepatol. 2002;37:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isse K, Harada K, Zen Y, Kamihira T, Shimoda S, Harada M, Nakanuma Y. Fractalkine and CX3CR1 are involved in the recruitment of intraepithelial lymphocytes of intrahepatic bile ducts. Hepatology. 2005;41:506–516. doi: 10.1002/hep.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnston B, Butcher EC. Chemokines in rapid leukocyte adhesion triggering and migration. Semin Immunol. 2002;14:83–92. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salmi M, Jalkanen S. Cell-surface enzymes in control of leukocyte trafficking. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:760–771. doi: 10.1038/nri1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kurkijarvi R, Yegutkin GG, Gunson BK, Jalkanen S, Salmi M, Adams DH. Circulating soluble vascular adhesion protein 1 accounts for the increased serum monoamine oxidase activity in chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1096–1103. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stolen CM, Yegutkin GG, Kurkijarvi R, Bono P, Alitalo K, Jalkanen S. Origins of serum semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase. Circ Res. 2004;95:50–57. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134630.68877.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McNab G, Reeves JL, Salmi M, Hubscher S, Jalkanen S, Adams DH. Vascular adhesion protein 1 mediates binding of T cells to human hepatic endothelium. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:522–528. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merinen M, Irjala H, Salmi M, Jaakkola I, Hanninen A, Jalkanen S. Vascular adhesion protein-1 is involved in both acute and chronic inflammation in the mouse. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:793–800. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62300-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edwards S, Lalor PF, Nash GB, Rainger GE, Adams DH. Lymphocyte traffic through sinusoidal endothelial cells is regulated by hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2005;41:451–459. doi: 10.1002/hep.20585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mamdouh Z, Chen X, Pierini LM, Maxfield FR, Muller WA. Targeted recycling of PECAM from endothelial surface-connected compartments during diapedesis. Nature. 2003;421:748–753. doi: 10.1038/nature01300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bardin N, Blot-Chabaud M, Despoix N, Kebir A, Harhouri K, Arsanto JP, Spinosa L, Perrin P, Robert S, Vely F, Sabatier F, Lebivic A, Kaplanski G, Sampol J, gnat-George F. CD146 and its Soluble Form Regulate Monocyte Transendothelial Migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.183251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reymond N, Imbert AM, Devilard E, Fabre S, Chabannon C, Xerri L, Farnarier C, Cantoni C, Bottino C, Moretta A, Dubreuil P, Lopez M. DNAM-1 and PVR regulate monocyte migration through endothelial junctions. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1331–1341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karlmark KR, Weiskirchen R, Zimmermann HW, Gassler N, Ginhoux F, Weber C, Merad M, Luedde T, Trautwein C, Tacke F. Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+ monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:261–274. doi: 10.1002/hep.22950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, Wu S, Lang R, Iredale JP. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jalkanen S, Salmi M. Cell surface monoamine oxidases: enzymes in search of a function. EMBO J. 2001;20:3893–3901. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marttila-Ichihara F, Smith DJ, Stolen C, Yegutkin GG, Elima K, Mercier N, Kiviranta R, Pihlavisto M, Alaranta S, Pentikainen U, Pentikainen O, Fulop F, Jalkanen S, Salmi M. Vascular amine oxidases are needed for leukocyte extravasation into inflamed joints in vivo. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2852–2862. doi: 10.1002/art.22061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]