Abstract

The current study investigated the heterogeneity of borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptoms in a sample of 382 inner-city, predominantly African-American male substance users through the use of Latent Class Analysis (LCA). A 4-class model was statistically preferred, with one class interpreted to be a “baseline” class, one class interpreted to be a “high BPD” class, and two classes interpreted as intermediate classes. As a secondary goal, we examined the resulting BPD classes in respect to relevant clinical correlates, including: temperamental vulnerabilities (affective instability, impulsivity, and interpersonal instability), childhood emotional abuse, drug choice, and co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders. The high BPD class evidenced the highest levels of the temperamental vulnerabilities and environmental stressors, the baseline class evidenced the lowest levels, and the two intermediate classes fell in between. Additionally, the high BPD class had a higher probability of cocaine and alcohol dependence, as well as mood and anxiety disorders than the baseline class. Rates of alcohol use and mood disorders for the intermediate classes fell in between the high BPD and the baseline class. Results are discussed in relation to the current diagnostic conceptualization of BPD.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder, Latent Class Analysis, Inner-City Substance Users, Diagnostic Heterogeneity

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by a pervasive pattern of affective instability, impulsivity, and unstable interpersonal relationships (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Gunderson, 2001; Linehan, 1993; Skodol et al., 2002), as well as a marked dysregulation of mood and behavior. Indeed, approximately 80% of individuals with BPD have a history of deliberate self-harm (e.g., Bohus et al, 2000), and 50% to 75% of those with BPD attempt suicide at least once (Fyer, Frances, Sullivan, Hurt, & Clarkin, 1988). Beyond simply self-injurious behaviors, individuals with BPD exhibit heightened levels of numerous other health-compromising behaviors, including risky sexual behavior, substance misuse, and binge eating (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Zanarini et al., 1998). Further, BPD frequently co-occurs with a number of Axis I disorders including but not limited to mood (Bunce & Coccaro, 1999; Zanarini et al, 1998), anxiety (McGlashan et al., 2000, Skodol et al., 1995, Zanarini et al., 1998, Zimmerman and Mattia, 1999), eating (Wonderlich & Swift, 1990), and substance use (Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, & Burr, 2000) disorders.

In attempting to understand the etiology, nature, and consequences of BPD, theoretical and empirical literature has debated whether BPD is better conceptualized as a diagnostic class (i.e., the presence or absence of a disorder) or as occurring along a continuous dimension. Recent factor analytic and taxometric research has suggested that BPD may be better conceptualized as a continuum, ranging from normal functioning to psychopathology (Edens, Marcus, & Ruiz, 2008; Rothschild, Cleland, Haslam, & Zimmerman, 2003; Trull et al. 2003; Wilberg et al. 1999). Moreover, the BPD diagnosis has been criticized for its potential heterogeneity (Clarkin et al, 1983), with the requirement that individuals meet only five of nine DSM-IV criteria resulting in substantial differences among individuals meeting criteria for the disorder (Skodol et al, 2002). Further, researchers have argued that the dichotomous diagnostic system may overlook important clinical information and fail to capture the true nature and extent of borderline personality pathology (McGlashan, 1987).

The argument for a dimensional conceptualization of borderline personality pathology notwithstanding, there are important reasons at both a practical and theoretical level to retain a categorical conceptualization of BPD. In general, a diagnostic or class system facilitates conceptualization, communication, and decision making among professionals. Moreover, in a clinical setting, a dimensional model is frequently perceived as unnecessarily complex, given that clinical decisions (i.e., referrals to treatment) are made on the basis of a membership in a diagnostic class. Specific to BPD in particular, this disorder is one of the two personality disorders for which a threshold/class model has been supported (Spitzer, Endicott, & Gibbon, 1979). Finally, given that BPD is considered to be a multidimensional disorder (see Paris, 2007), a dimensional system that accounts for all its complexity would require creating multiple complex profiles to define patients presenting with symptoms of BPD (likely leading to a complex and unwieldy dimensional description).

Thus, although both the dimensional and categorical approaches present unique benefits for the understanding of BPD, both approaches also have limitations. As such, research examining the relevance and utility of alternative classification systems that capitalizes on the benefits of both approaches is needed. This alternative approach to the current classification system would more closely approximate the underlying latent continuum of BPD (compared to the current diagnostic scheme), while also retaining clinical utility and addressing the limitations inherent in a more complex dimensional approach.

One such alternative to the traditional symptom count is latent class analysis (LCA; Lazarsfeld & Henry, 1968; McCutcheon, 1987), a latent variable modeling framework that models the dependence of items on a discrete latent variable capturing unknown class membership. LCA results in both the classification of subjects into classes and the characterizations of items in terms of their differential utility in distinguishing between classes. In its application, LCA offers an alternative method for classifying individuals, providing an empirical, data-driven method of classifying individuals (in contrast to diagnostic cutoffs and symptom counts). This approach has several benefits, as compared to the polythetic diagnostic system. First, classes derived from the LCA analysis can be thought of as discretized versions of a latent continuum, and thus, more closely approximate the underlying structure of BPD. Indeed, discrete latent variable and continuous latent variable models can be shown to be statistically equivalent modeling choices. Moreover, LCA allows for categorizing individuals based on key indicators (e.g., self-harm), rather than a symptom count; as such, this approach allows for key items to be differentially informative in obtaining the classifications. Finally, this approach allows the placement of individuals who would previously be categorized as non-BPD into groups based on such key indicators. As such, LCA may be a particularly useful classification method that unites the benefits of a categorical and dimensional system.

A growing body of literature suggests the utility and relevance of the LCA approach as an alternative classification system for BPD. First, Fossati et al. (1999) examined a sample of psychiatric patients and found evidence for three latent classes of BPD: a group with high levels of BPD symptoms, a group with low levels of BPD symptoms, and an intermediary group that did not meet criteria for BPD, but had a high probability of endorsing the “impulsivity” and “inappropriate anger” diagnostic criteria. Thus, these particular diagnostic criteria were relatively weak at differentiating between the “high BPD” and “intermediary” classes. Moreover, the investigators found almost perfect agreement between the “high BPD” class and individuals meeting DSM-IV criteria for BPD, with both the “low BPD” and “intermediate” classes capturing individuals who did not meet criteria for a BPD diagnosis. In another study, Thatcher et al. (2005) examined a sample of young adults presenting with alcohol use problems who endorsed at least one item on the BPD interview. Results indicated a three-class solution: a severe class (elevated on all criteria), a moderate class (with relatively lower rates of symptoms), and an impulsivity class (that endorsed primarily the impulsivity and inappropriate anger criteria). The three groups were differentially related to adolescent alcohol use disorders, conduct disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and major depression, with the severe class demonstrating the highest rates of these disorders.

Clifton and Pilkonis (2007) examined a more general sample (drawing from psychiatric inpatient, psychiatric outpatient, medical, and university settings). The best-fitting LCA model divided individuals into one of two latent classes: those with significant borderline pathology and those without. Analysis of clinical dysfunction across the two classes revealed that those falling into the “high BPD class” had higher levels of anxiety and depression, as well as higher levels of interpersonal dysfunction. Further, the authors reported that this “high BPD” class was somewhat less stringent than the DSM-IV BPD diagnosis, including some individuals who did not meet DSM-IV criteria for BPD (as well as those who did). Finally, Shevlin, Dorahy, Adamson, and Murphy (2007) examined a non-clinical sample drawn from private households in the UK and found evidence for a 4-class model of BPD, including a baseline or normative group, a “high class” (having high probability of endorsement of all symptoms), and two intermediate groups that were similar in profile. Additionally, the “high class” had a higher likelihood of psychiatric comorbidity, adverse life events, and suicide, compared to the “baseline” class, with the intermediary classes higher on suicide, anxiety, and depressive disorders than the “baseline” class. Analyses examining the utility of the individual items indicated that identity disturbance, impulsivity, parasuicidality, and affective instability were relatively poor differentiators between classes, while items reflecting efforts to avoid abandonment, stormy interpersonal relationships, chronic feelings of emptiness, inappropriate anger, and transient paranoia and/or dissociation were better differentiators of classes. Information regarding the overlap of these classes with the DSM-IV BPD diagnosis was not provided.

Altogether, the findings from these studies suggest that the utility of an LCA approach for understanding BPD pathology, providing evidence for the existence of discrete classes of BPD. However, there is still no consensus on the precise latent class structure of BPD vis-à-vis either the number of latent classes (two vs. three vs. four classes) or the relevance of certain criteria (e.g., the inferential importance of inappropriate anger on differentiating between classes). The most likely explanation for this disparity is that the number and nature of these classes varies depending on the type of population being studied; however, this conclusion is difficult to make, as all of these studies included samples of predominantly White, middle class participants. Indeed, no studies to date have utilized LCA to examine latent classes in more diverse clinical samples. One such notable sample is inner-city substance users – a population previously demonstrated to be at heightened risk for the presence of BPD (Romero-Daza et al., 2003; Trull et al., 2000). Yet, despite this, relatively little research has examined BPD within this population and, as mentioned above, no studies have examined the latent classes of BPD symptoms within this population.

Current Study

The current study extends previous investigations of latent classes of BPD symptoms by examining the presence and structure of BPD classes within a more diverse and underserved sample of inner-city drug users. Moreover, to provide further information on the clinical utility/relevance of these latent classes, their associations with a range of BPD-relevant clinical correlates were examined. Specifically, we examined associations between the latent classes and theorized risk factors, associated conditions, and drug of choice (a particularly relevant correlate in this sample, given past findings that certain drug types are associated with elevated rates of risk behaviors; see Joe & Simpson, 1995). With regard to the hypothesized risk factors for BPD, we examined the relationships between our classes of BPD and three temperamental vulnerabilities thought to be central to BPD: affective instability (i.e., marked, reactive shifts in mood; Siever & Davis, 1991; Siever et al., 2002; Skodol et al., 2002 Livesley et al., 1992, 1998), impulsivity (inability to withhold responding in the presence of a potentially rewarding stimulus, Siever & Davis, 1991; Skodol et al., 2002; Clarkin et al., 1993; Wilberg et al., 1999; Morey et al., 2002), and interpersonal instability (i.e., vacillation between extremes of idealization and devaluation in interpersonal relationships; Agrawal, Gunderson, Holmes, & Lyons-Ruth, 2004; Gunderson, 2005; Gunderson et al., 2006). We also examined the extent to which our classes of BPD were associated with emotional abuse, one of the predominant environmental risk factors found to be associated with heightened risk for BPD in general (Bernstein, Stein, & Handelsman, 1998; Zanarini et al, 1997), and among substance users in particular (see Bornovalova et al., 2006; Gratz et al., 2008). With regard to associated conditions, given evidence that BPD frequently co-occurs with mood and anxiety disorders (Zanarini et al, 1998), we examined rates of these disorders across classes of BPD. Finally, given preliminary literature suggesting that those with BPD are more likely to endorse alcohol (Linehan et al, 1999) and cocaine (Flynn et al., 1995) dependence (vs. other drug classes), we examined the association of BPD classes and particular types of substance dependence (namely, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, opiates/heroin, and PCP).

Method

Participants

As part of three large studies, 382 inpatient residents in a drug and alcohol abuse treatment center in the greater Washington DC metropolitan area completed questionnaire packets and a structured clinical interview for BPD (see below). Treatment at this center involves a mix of strategies adopted from Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous as well as group sessions focused on relapse prevention and functional analysis. The center requires complete abstinence from drugs and alcohol (including any form of pharmacological treatment, such as methadone), with the exception of caffeine and nicotine; regular drug testing is provided and any substance use is grounds for dismissal. Typical treatment lasts between 30 and 180 days and, aside from scheduled activities (e.g., group retreats, physician visits), residents are not permitted to leave the center grounds during treatment.

The sample ranged in age from 18 to 68, with a mean age of 41.57 (SD = 9.24). Approximately two-thirds (68.3%) of the participants were male, and 90.2% were African-American. With regard to highest education level achieved, 24% had not completed high school or received a GED, 39.8% had completed high school or received a GED, and 36.2% had attended at least some college or technical school. The mean income was $21,400 (SD = $29,100), and most were not living with a partner (68.6%).

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

A short self-report questionnaire was administered to obtain information on age, gender, race, education level, marital status, and income.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Axis II (SCID-II; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, and Benjamin)

The SCID-II, a measure that produces reliable scores (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1995), was used to assess for the presence of BPD. For the current study, the majority of the interviews were conducted by the first author, trained in the administration of the interview, with the rest conducted by a trained clinical research assistant. Twenty-five percent of the interviews were reviewed by a PhD-level clinician (Lejuez). In the three cases for which there was a discrepancy, a consensus was reached. The interviewers had no access to participant self-report answers on corresponding questionnaires.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-NP, non-patient version)

Lifetime prevalence of mood, anxiety, and alcohol and non-alcohol substance dependence diagnoses was determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID–NP, non-patient version; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995). This measure has been shown to produce reliable scores that support inferences with demonstrated validity (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1989). In the current study, all diagnostic interviews were conducted by the first author. Twenty-five percent of the interviews were reviewed by the fourth author (Lejuez). No discrepancies were found between the first author’s and last author’s diagnostic decisions.

Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire-Stress Reactivity and Alienation Scales (Patrick et al., 2002)

The MPQ-BF is a 155-item version of the original 300-item MPQ (Tellegen, 1982), developed to assess a variety of personality traits and temperamental dispositions. Like the original MPQ, the MPQ-BF includes 11 primary trait scales which load onto three higher-order factors. The traits of Well-Being, Achievement, Social Closeness, and Social Potency load onto the higher-order factor of Positive Emotionality; the traits of Stress Reactivity, Alienation, and Aggression make up the higher-order factor of Negative Emotionality; the traits of Control, Harm Avoidance, and Traditionalism load on the higher-order factor of Constraint; and the trait of Absorption does not load on any of the higher-order factors. Scores from the traits scales of the MPQ-BF are highly correlated with the equivalent trait scales from the original MPQ (r’s ranged from .92 to .96) and have demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas range from 74 to .84; see Patrick et al., 2002).

The current study utilized two subscales of the MPQ-BF. The Stress Reactivity scale was used to measure the temperamental disposition of emotional instability and the Alienation scale (measuring interpersonal manifestations of negative temperament) was used to measure the disposition of interpersonal instability. In the current sample, alphas for the stress reactivity and alienation scales were .85 and .91, respectively.

Eysenck Impulsiveness Scale (Eysenck et al., 1985) and UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale (Whiteside and Lynam, 2001)

Approximately two-thirds of the participants completed the Eysenck Impulsiveness Scale (S.B.G. Eysenck et al., 1985). The EIS measures impulsive behavior across cognitive and behavioral domains and consists of 19 items (scores range from 0 to 19, with higher scores indicating higher levels of impulsivity). Past studies indicate that the scale scores has good internal consistency with αs ranging from 0.84 to 0.87 (Eysenck et al., 1985; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001), and a number of studies provide support for the construct validity for inferences based on the scale. For instance, Lejuez et al. (2002) found that the EIS was significantly related to other measures of impulsivity, as well as to other related dimensions of disinhibition (e.g., sensation-seeking and risk-taking). Further, evidence has been provided for the predictive validity of EIS scores, with findings indicating that the EIS is related to the number of drug classes tried in the past year, as well as the total score on an alcohol use screen. This scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the current sample, with an alpha of .83.

Due to a change in protocol in one of the larger studies, the remaining one-third of participants completed the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS) instead of the EIS. The 44-item UPPS assesses four distinct facets of personality associated with impulsive behavior: urgency, (lack of) premeditation, (lack of) perseverance, and sensation seeking, with higher scores indicating higher levels of impulsivity. The UPPS has been found to have good internal consistency (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001), as well as good convergent and divergent validity. Specifically, previous work has found differential relationships between the four UPPS subscales and various facets of alcohol use, with the urgency and lack of perseverance subscales being associated with alcohol related problems, and premeditation and sensation-seeking being related to quantity and frequency of use (Magid & Colder, 2007). The internal consistency within this sample was good (α = .88).

Given the conceptual overlap between these two measures of impulsivity (see Whiteside and Lynam, 2001 for a review), scores on each were converted into z-scores and combined to create an impulsivity variable.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form, Emotional Abuse Subscale (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2003)

The CTQ-SF is a 28-item measure that assesses childhood maltreatment experiences (i.e., “while you were growing up”) using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true) across physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect. Findings among a sample of adult substance abusers indicate that CTQ scores have adequate internal consistency, as well as good test-retest reliability over a period of greater than 1 month (r = .86, p < .01; see Bernstein & Fink, 1998). Additionally, scores on the CTQ are significantly correlated with independent ratings of trauma (Bernstein et al., 1997, 2003). The current study utilized the CTQ-SF emotional abuse subscale only. This subscale contains 5 items assessing emotional abuse. It warrants mention that emotional abuse has been shown to be highly correlated with sexual and physical abuse in past studies (e.g., Bornovalova et al., 2006 Bernstein et al., 1994, 1997; Medrano, Hatch, Zule, & Desmond, 2002), and that studies have shown that physical, emotional, and sexual abuse tend to highly co-occur (Dong et al, 2004; Roth et al., 1997). Further, recent studies have found that emotional abuse in particular (vs. other forms of abuse) is uniquely associated with BPD among inner-city substance users (Bornovalova et al., 2006; Gratz et al., 2008). In the current study, internal consistency of the emotional abuse subscale was good (α = .84).

Procedure

Prior to participating, all participants provided written informed consent. After this, participants completed the BPD module of the SCID-II, and the mood, anxiety, and alcohol and non-alcohol substance dependence modules of the SCID-I. Following the interview, participants completed a self-report questionnaire packet including the measures described above. Measures were randomly sequenced across participants to limit order effects. Participants were actively encouraged to seek assistance regarding questions that were unclear. At least one male and one female researcher were available at each session to provide participants with a same-sex individual for queries regarding the questionnaires.

Results

Initial LCA Results

Latent class models were fit to the item response data on the BPD SCID-II items to model the structure of the polytomous observables on a latent class membership variable. A sequence of models was fit via Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2006), obtaining 2- through 5-class solutions. The estimation of each model was run with 100 random sets of start values and ten final stage optimizations to help ensure that the resulting estimates are based on global rather than local maxima of the likelihood. Model selection was based on interpretability of parameter estimates and comparative data-model fit in terms of information criteria and hypothesis tests. For each model, the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (LRT) based on 100 bootstrapped draws (McLachlan & Peel, 2000) were conducted at the α=.05 level of significance; p< α indicates that the k-class model fit during the analysis provides better fit than a (k−1)-class model. In addition, the sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SS-BIC; Sclove, 1987) was obtained for each model, for which smaller values indicate better fit, were evaluated. Methodological research has shown that the bootstrap LRT and the SS-BIC are the preferred test and information criterion for selecting the number of classes for latent class models of data structures comparable to that in the current study (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). Table 1 contains fit information for LCA models. The log-likelihood values indicate that each successive model provides better fit, as the additional flexibility that comes with modeling an additional class allows for better approximations to data. The results of the bootstrap LRT indicate that the fit of the 4-class model provides statistically significantly better fit than the 3-class model; however the 5-class model does not provide statistically significantly better fit than the 4-class model. Likewise, the results of the SSA-BIC support the 4-class model.

Table 1.

Fit results for latent class model

| Model | Log-Likelihood | Bootstrap LRT p | SS-BIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-class | −2509.95 | 0.00 | 5122.49 |

| 3-class | −2466.13 | 0.00 | 5087.53 |

| 4-class | −2438.50 | 0.02 | 5084.94 |

| 5-class | −2415.13 | 0.14 | 5090.89 |

Because it is reasonable to hypothesize that there might be gender differences in the response style and rates of item endorsement that would influence the model, we considered two additional models. The first included gender as a covariate with a direct effect on latent class membership. Findings indicated that gender was associated with class membership, suggesting that women are more likely than men to fall into classes 3 and 4. The second model included gender as a covariate with a direct effect on latent class membership as well as direct effects on each of the observed symptoms, effectively modeling measurement noninvariance over groups defined by gender. This latter model did not provide statistically better fit according to the information criteria (SS-BIC of 4969.281 and 4969.578, respectively); the estimated latent class proportions and conditional probabilities did not differ meaningfully between the original model without gender and the models with gender included, suggesting that the classes are not being driven by response style differences for the symptoms. Specifically, the data support the conclusion that although class membership is related to gender, the classes are not proxies for gender or defined in terms of gender-specific measurement noninvariance. Accordingly, we have retained the original analysis that does not include gender as a covariate in the model, ensuring that the definition of the latent classes is strictly in terms of the symptoms as indicators of the construct (Masyn, 2009; Nylund-Gibson, 2009).

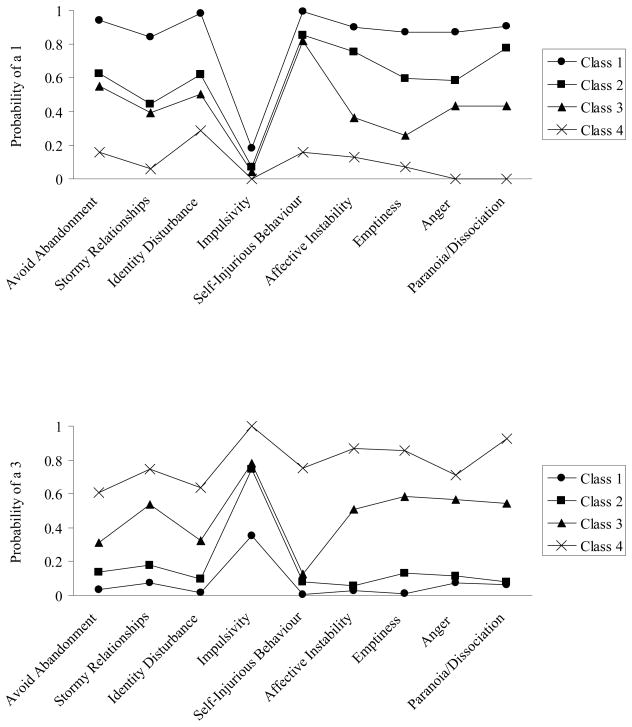

The panels in Figure 1 plot the conditional probabilities of scoring a 1 or 3 on each of the SCID-II items, revealing an interpretable latent class structure. Panel 2 of Figure 1 reveals that for all items, the probability of responding with a 3 is highest for class 4, next highest for class 3, next highest for class 2, and lowest for class 1. Consistent with this structure, the ordering of classes is reversed for the probabilities of responding with a 1 (Figure 1, Panel 1).

Figure 1.

Conditional probabilities of endorsing a 1 (Panel 1) and 3 (Panel 2) for each of the nine BPD items from the 4-class solution

Class 1, the largest class in the analysis (40.02% of the sample) is interpreted as a “baseline” class of subjects not reporting notable BPD pathology. Class 4 (7.71%) is characterized by high probabilities of responding with a 3 and low probabilities of responding with a 1 for all items, and is interpreted as the “high BPD” class. Classes 2 and 3 are intermediate classes of comparable size (25.30 % and 26.97%, respectively). The distinctions between classes 2 and 3 are revealed most clearly through the discrepancy in the probabilities of members of these classes responding to items 2 (stormy relationships) and 6–9 (affective instability, emptiness, anger, paranoid ideation/dissociation, respectively). For items 6–9, class 3 has higher probabilities of responding with a 3, whereas class 2 has higher probabilities of responding with a 1. For item 2, these classes have comparable probabilities of responding with a 1; class 3 has a higher probability of responding with a 3 and class 2 has a higher probability of responding with a 2. Accordingly, we refer to class 2 as a “low intermediate” class and class 3 as a “moderate” class. The baseline class and the low intermediate class are quite similar in their probabilities of responding with a 3 to most items. Differences between these classes are revealed in terms of (a) item 4, in which members of the baseline class are more likely to respond with a 2 while members of the low intermediate class are more likely to respond with a 3 and (b) items 1–3 (avoidance of abandonment, stormy relationships, identity disturbance) and 7–8 (emptiness, anger), for which members of the baseline class are more likely to respond with a 1 and members of the low intermediate class are more likely to respond with a 2.

Consideration of the conditional probabilities of the responses (Figure 1) revealed that the items were differentially useful for distinguishing between classes. Specifically, items 1 (avoidance of abandonment) and 5 (self-injurious behavior) served to distinguish the high BPD class from the remaining classes. Consideration of a number of the other items again revealed the utility of employing polytomous models, such that several classes (i.e., the two intermediate classes) could be distinguished by their responding with a 2 versus a 3. Specifically, on item 2, the low intermediate class had a higher probability of responding with a 2 and the moderate class had a higher probability of responding with a 3. A similar interpretation can be advanced for item 3 (identity disturbance). These findings further support the interpretation of class 2 as the lower intermediate class and class 3 as a more moderate class. Note that the intermediary classes have nearly identical probabilities for items 4 and 5 (impulsivity and self-injurious behavior, where impulsivity was uniformly high across all classes, and self-injurious behavior was low in both intermediate classes); as such, these items did not aid in distinguishing between the two intermediate classes. It should also be noted that item 4 (impulsivity) failed to distinguish between the intermediate and high BPD classes, with all of these three classes having low probability of responding with a 1.

Relationships between these Classes and DSM-IV-Based BPD Diagnosis

With regard to the relationships between the four classes identified by the LCA and the DSM-IV-based BPD diagnosis, results indicate that the LCA used here resulted in the identification of a high BPD class that is likely a more conservative (and homogeneous) class than that provided by a BPD diagnosis. First, we examined the percentage of participants in each class that met criteria for BPD using the DSM-IV classification (i.e., 5 or more symptoms endorsed on the SCID-II). Of the baseline class (n = 162), 0.6% met criteria for BPD; of the low intermediate class (n = 86), 1.2% met criteria for BPD; of the moderate class (n = 103), 39.8% met criteria for BPD; and of the high BPD class (n = 31), 96.8% met criteria for BPD (endorsing 5 or more of the BPD criteria). Second, analyses indicated that out of 73 participants who endorsed 5 or more criteria for BPD on the SCID-II, 1 (.01%) fell into the baseline class, 1 (.01%) fell into the low intermediate class, 41 (56.2%) fell into the moderate class, and 30 (41.1%) fell into the high BPD class. The omnibus chi-square analysis examining rates of different classes among individuals with BPD (and rates of BPD across each of the classes) was significant (χ2 = 203.26 p < .001). Further, follow-up chi-square analyses indicated that rates of BPD differed significantly across all classes (χ2 values ranging from 31.04 to 178.45, p < .001), with one exception: rates of DSM-IV-based BPD diagnoses did not differ significantly between the baseline and low intermediate classes (χ2 = .21, p = .57).

Clinical Correlates of Class Probabilities

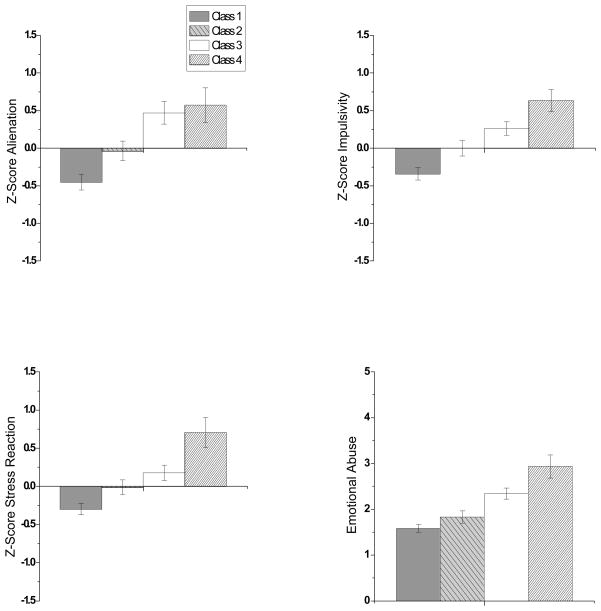

Following in the methodology of Shevlin and colleagues (2006), we utilized the best-fitting (4-class) model to test whether there were differences in demographic and clinical variables across classes. To do so, we conducted a number of univariate ANOVAS and ANCOVAS (See Figure 2) for continuous demographic (age and income) and clinical (stress reactivity, impulsivity, alienation, and childhood emotional abuse) variables. Chi-square analyses and multinomial logistic regressions were used to test class differences in dichotomous variables including gender, education, and ethnicity, as well as rates of comorbidity across mood and anxiety disorders and type of substances on which participants were dependent.

Figure 2.

Differences in stress reaction, impulsivity, alienation (z-scores) and levels of emotional abuse (raw scores) across the four classes of BPD symptoms

Demographic differences across classes

As shown in Table 2, participants in the four classes were compared on several demographic characteristics. A univariate ANOVA indicated that there was no relationship between class and age [F(3, 376) = 1.960; p = .12), ethnicity (χ2 =3.79; p = .28), marital status (χ2 =1.26; p = .74), or educational level (χ2 =9.61; p = .14). However, there was a main effect of class on total household income [F(3, 371) = 6.40; p < .001). Post-hoc LSD tests indicated that the baseline class had significantly higher income than all other classes (p < .05), with no other differences between classes. Moreover, consistent with the findings of the LCA models that included gender as a covariate, chi-square analyses revealed that there was a significant relationship between class and gender (χ2 =35.5; p < .01). Follow-up analyses indicated that the high BPD class had significantly higher rates of women than the baseline and low intermediate classes. Further, the moderate class had significantly lower rates of women than the high BPD class, but significantly higher rates of women than the baseline and low intermediate classes.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Demographic Variables among the Entire Sample and Group Differences between Classes

| Overall Mean (SD) | Baseline Mean (SD) | Low Intermediate Mean (SD) | Moderate Mean (SD) | High BPD Mean (SD) | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.57 (9.24) | 42.78 (9.89) a | 41.50 (8.79) a | 40.12 (9.21) a | 40.35 (6.28) a | F(3, 376) = 1.96; p = .12 |

| Total Household Income | 1.64 (2.41) | 2.25 (2.9) b | 1.31 (1.81) a | 1.17 (1.79) a | .901 (1.94) a | F(3, 371) = 6.40; p < .001 |

| Gender (% Male) | 68.3 | 78.4 a | 74.7 a | 58.8 c | 29 b | χ2 =35.5; p < .001 |

| Ethnicity (% African American) | 90.2 | 93.2 a | 90.5 a | 86.3 a | 87.1 a | χ2 =3.79; p = .28 |

| Marital Status (% Single) | 68.6 | 68.1 a | 70.5 a | 70.5 a | 57.9 a | χ2 =1.26; p = .74 |

| Education Level | χ2 =9.61; p = .14 | |||||

| Some High School | 24.0 | 17.3 | 26.2 | 29.4 | 35.8 | |

| High School graduate/GED | 39.8 | 43.2 | 41.7 | 33.3 | 38.7 | |

| Some College and above | 36.2 | 39.5 | 46.2 | 37.3 | 25.8 |

Note: Letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences between cells and/or lack thereof. Different letters indicate the presence of significant differences.

Temperamental vulnerabilities

Means for each raw and transformed variable across classes are presented in Table 3. A visual representation of these results is shown in Figure 2. A series of univariate ANCOVAS (controlling for gender and income) using class as the independent variable and a given temperamental dimension as the dependent variable was conducted. For stress reactivity, a significant effect of class was observed, [F(3, 353) = 11.53, p = .001, η2 = .09]. Follow-up LSD contrasts indicated that the high BPD class reported significantly higher levels of stress reactivity than the baseline, low intermediate, and moderate classes (all ps < .01), and the baseline class reported significantly lower levels of stress reactivity than the moderate class (p < .001) but not the low intermediate class (p = .73). The moderate class was not significantly different from the low intermediate class (p = .16).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Temperamental Vulnerabilities and Emotional Abuse

| Variable | Baseline Mean (SD) | Low Intermediate Mean (SD) | Moderate Mean (SD) | High BPD Mean (SD) | Significance Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impulsivity, raw score | |||||

| EIS | 8.70 (4.75) | 8.5000 (5.25) | 11.100 (3.96) | 12.33 (3.21) | |

| UPPS | 61.47 (7.57) | 65.06 (7.03) | 67.50 (7.24) | 70.0 (6.35) | |

| Stress Reaction, raw score | 5.57 (3.65) | 6.58 (3.61) | 7.20 (3.74) | 9.42 (4.23) | |

| Alienation, Raw score | 3.96 (2.60) | 4.96 (3.06) | 6.74 (3.14) | 7.13 (2.82) | |

| Impulsivity, Z-Score | −.34 (1.03) | −.00 (.93)8 | .26 (.91) | .64 (.80) | F(3, 371) = 13.52, p < .000 |

| Stress Reaction, Z-Score | −.30 (94) | −.01 (.88) | .18 (.99)7 | .71(1.08) | F(3, 361) = 11.56, p < .000 |

| Alienation, Z-Score | −.45(.86) | −.044(.82) | .47 (1.04) | .57 (.90) | F (3, 166) = 11.72, p < .000 |

| Emotional Abuse | 1.59 (.80) | 1.83 (.97) | 2.34 (1.05) | 2.93 (1.31) | F(3, 235) = 12.05, p = .001 |

A significant effect of class was also observed for impulsivity [F(3, 371) = 12.23, p = .001, η2 = .09]. Follow-up LSD contrasts indicated that the high BPD class reported significantly higher levels of impulsivity than the baseline and low intermediate classes (all ps < .01) and the difference between the high BPD and moderate classes approached significance (p = .06). Further, the baseline class had significantly lower levels of impulsivity than all other classes (ps < .01). The difference between the low intermediate and moderate classes was also significant (p < .05), with the moderate class indicating higher levels of impulsivity than the low intermediate class.

Finally, an examination of class differences in levels of alienation indicated a significant effect of class [F(3, 160) = 8.73, p = .001, η2 = .14]. Follow-up LSD contrasts indicated that the high BPD class reported significantly higher levels of alienation than the baseline and low intermediate classes (all ps < .01), but not the moderate class (p = .92). On the other hand, the baseline class had significantly lower levels of alienation than all other classes (all ps < .001). Further, the moderate class evidenced higher levels of alienation than the low intermediate and baseline classes (p < .05).

Levels of emotional abuse across classes

A univariate ANCOVA with class entered as the independent variable and emotional abuse entered as the dependent variable was used to examine differences in levels of emotional abuse across classes [see Table 3 for mean (SD) and Figure 2 for visual representation]. Because there were significant differences in gender and income across classes (see above), these two variables were entered into the model as covariates. The ANCOVA revealed a significant effect of class [F(3, 235) = 12.05, p = .001, η2 = .145], see Figure 2. Follow-up LSD contrasts indicated that the high BPD class reported significantly higher levels of emotional abuse than the baseline, low intermediate, and moderate classes (all ps < .01), and the baseline class had significantly lower levels of emotional abuse than the moderate and high BPD classes (ps < .001). The difference between the low intermediate and moderate classes was also significant (p < .05), with the moderate class reporting a higher level of emotional abuse than the low intermediate class.

Psychiatric comorbidity

The current study assessed for a number of mood and anxiety disorders, including past and present major depression, bipolar I and II disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder. However, preliminary analyses revealed small ns for many of these specific disorders within each class cell. Thus, for the purposes of the following analyses, we collapsed bipolar I and II disorder and past and present major depression into a category of “mood disorders,” and generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder into the category of “anxiety disorders”.

The percentages of Axis I disorders (i.e., mood and anxiety disorders, substance use disorders) across classes are presented in Table 4. In addition to examining differences in the rates of these disorders across the classes, we controlled for gender and income in a multinomial logistic regression to assess the association between the latent classes and psychiatric comorbidity and drug dependence classes (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, heroin, cocaine, and PCP; see Table 5). Regarding psychiatric comorbidity, results indicated that members of the high BPD class were more likely to be diagnosed with mood (OR = .20; p = .012) and anxiety (OR = .16, p = .013) disorders than members of the baseline class. Further, compared to members of the baseline class, members of the moderate class are more likely to be diagnosed with mood (OR = .28; p = .002) disorders, although not anxiety disorders (OR =.85, p = .85). Finally a series of post-hoc logistic regressions aimed at elucidating differences between intermediate, moderate, and high BPD classes was conducted. Findings indicated that although members of the high BPD class were no more likely to meet criteria for a mood disorder than members of the moderate class (OR = 1.27; p = .72), they were more than three times more likely to meet criteria for an anxiety disorder (OR = 3.17); however, likely due to the small N in this analysis, this difference did not reach significance (p =.15). Further, compared to members of the low intermediate class, members of the high BPD class were eight times more likely to meet criteria for an anxiety disorder (OR = 8.97; p = .04), and almost four times more likely to meet criteria for a mood disorder (although this difference did not reach significance; OR = 3.81; p = .09). Finally, results indicated no significant differences between the low intermediate and moderate classes in rates of mood (OR = .46; p = .14) or anxiety (OR = 1.17; p = .85) disorders.

Table 4.

Percentage of sample meeting diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders and omnibus chi-square results

| Diagnosis | Overall | Baseline | Low Intermediate | Moderate | High BPD | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood Disorders | 38.8 | 27.5 | 36 | 56.1 | 57.1 | χ2 =11.54; p = .009 |

| Anxiety Disorders | 12.5 | 8.8 | 12 | 12.2 | 35.7 | χ2 =7.94; p = .047 |

| Substance Dependence | ||||||

| Alcohol | 34.2 | 27.3 | 30 | 42.6 | 51.6 | χ2 =10.78; p = .01 |

| Cannabis | 13.6 | 9.3 | 15.7 | 21.3 | 6.5 | χ2 =8.64; p = .03 |

| Heroin | 37.1 | 39.3 | 37.1 | 36.2 | 29.3 | χ2 =1.2; p = .74 |

| Cocaine | 65.1 | 55.3 | 68.6 | 69.1 | 93.3 | χ2 =17.88; p < .01 |

| PCP | 4.6 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 0 | χ2 =1.89; p = .6 |

| Number of Drug dependence categories endorsed | 1.55 (.81) | 1.37 (.80) | 1.57 (.73) | 1.73 (.81) | 1.80 (.80) | F(3, 340) = 5.29; p = .01 |

Table 5.

Comparisons of Substance Use Disorders And Other Psychopathology With Class 1 (Baseline Class), While Controlling For Gender And Income

| Diagnosis | Low Intermediate OR, 95% CI, p | Moderate OR, 95% CI, p | High BPD OR, 95% CI, p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mood Disorders | .63; .24–1.66; .35 | .28; .12–.64; .002 | .20; .06–.71; .012 |

| Anxiety Disorders | .70; .17–2.95; .63 | .85; .23–3.12; .85 | .16; .04–.69; .013 |

| Substance Dependence | |||

| Alcohol | .96, .50–1.83, .89 | .52; .29–.92, .024 | .35, .15–.81, .014 |

| Cannabis | .53, .22–1.24, .14 | .40, .19–.88, .02 | 1.42, .29–6.86, .67 |

| Heroin | 1.17, .64–2.14, .61 | 1.06, .61–1.86, .83 | 1.34, .55–3.25, .52 |

| Cocaine | .63, .34–1.18, .15 | .72, .41–1.29, .27 | .14, .03–.63, .01 |

| PCP | .88, .25–3.1, .85 | 1.16, .33–4.13, .81 | N/A (0%) |

| Number of drug dependence categories endorsed (class 1 denoted as a; different letters indicate significant comparisons) | F(3, 330) = 3.39; η2 = .03; p = .018 | ||

| a | b | b | |

Regarding differences in rates of dependence across the various drug classes, results indicate that members of the high BPD class were more likely to be dependent on alcohol (OR = .35, p = .014) and cocaine (OR = .14, p = .01) than members of the baseline class. Interestingly, no participants (0%) in the high BPD class were dependent on PCP. Likewise, members of the moderate class were more likely than members of the baseline class to be dependent on alcohol (OR = .52; p = .024) and cocaine (OR = .40, p = .02). Rates of drug dependence diagnoses did not differ significantly between the baseline and low intermediate classes (ps > .10). With regard to differences between the low intermediate, moderate, and high BPD classes, results indicated that members of the high BPD class were almost five times more likely to meet criteria for cocaine dependence than the low intermediate (OR = 4.74; p = .06) and moderate (OR = 4.67; p < .05) classes, and almost four times more likely to meet criteria for alcohol dependence than the low intermediate class (OR = 3.98; p = .01). Rates of cocaine and alcohol dependence did not differ significantly between the low intermediate and moderate classes (ORs < .81, 1.73, respectively; both ps > .10), and rates of alcohol dependence did not differ significantly between the high BPD and moderate classes (OR = 1.3; p = .52). Further, rates of heroin, cannabis, and PCP did not differ significantly between any of the classes (list of comparisons: low intermediate versus moderate, high BPD and low intermediate, high BPD and moderate; ORs < 1.13; .65; .78 for heroin; 1.25; .45; .27 for cannabis; .73; .00; .00 for PCP; all ps > .10).

Discussion

The present study provides a replication and extension of previous work examining latent classes of BPD symptoms (i.e., Fossati et al., 1999; Clifton & Pilkonis, 2007; Shevlin et al., 2007) in an underserved sample shown to be at risk for BPD: inner-city substance users (Casillas & Clark, 2002; Fleming et al., 1998; Jasinski et al., 2000). Results of the present study indicate that a 4-class model was statistically preferred, with one class interpreted to be a baseline class, one class interpreted to be a high BPD class, and two classes interpreted as intermediate classes.

These results are most similar to the findings of Shevlin et al. (2007) and Thatcher et al. (2005). Indeed, not only did Shevlin et al. find evidence for a four-class model of BPD symptoms (i.e., a normative group, a “high symptom class” group, and two intermediate groups), they also reported the same patterns of associations between BPD classes and emotional functioning/psychopathology. For example, consistent with the findings from the present study, Shevlin et al. reported the strongest association of mood, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders with the high BPD class, but a considerably smaller association with the intermediate classes. Similarly, Thatcher et al. (2005) found that the high BPD class was the most likely to meet criteria for alcohol use disorders, disruptive disorders, and major depression, whereas the moderate, “impulsivity”, and symptom-free classes (i.e., individuals who did not endorse any BPD criterion) were less likely to meet criteria for co-occurring psychopathology. The similarity between our findings and those of Shevlin et al. and Thatcher et al. cannot be accounted for by similar samples or sample sizes; instead, the convergence across these three studies provides some support for the relevance and generalizability of a four-class model of BPD pathology.

Findings also indicated that the BPD diagnostic criteria are differentially useful for distinguishing between classes within this population. For example, criteria pertaining to fears of abandonment and self-injurious behaviors were found to be the strongest criteria for distinguishing the high BPD class from the other classes, suggesting that these criteria may be particularly central to and representative of BPD pathology. In contrast, the item pertaining to impulsive behaviors was uniformly high across classes, failing to distinguish between the different classes. Although this could arguably be due to the presence of elevated impulsivity among the sample in general (given evidence that drug users demonstrate heightened impulsivity; Kirby, Petry, & Bickel, 1999; Krueger et al., 2002), it is important to note that both Shevlin et al. (2007) and Fossatti (1999) also found evidence for the relative weakness of the impulsivity item in distinguishing between any of their latent classes. As such, a growing body of evidence suggests that the BPD diagnostic criterion of impulsivity may be relatively weak in distinguishing between latent BPD classes.

The current study also examined the relationships between the modeled latent classes and clinical correlates of BPD, including temperamental vulnerabilities (emotional instability, impulsivity, and interpersonal instability), childhood emotional abuse, drug choice (with a focus on alcohol, cocaine, heroin, cannabis, and PCP dependence), and co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders. With regard to the putative risk factors for BPD (i.e., the temperamental vulnerabilities and emotional abuse), results indicated a monotonic relationship of these variables across classes, such that those in the high BPD class evidenced the highest levels of these risk factors, those in the baseline class evidenced the lowest levels of these risk factors, and those in the intermediate classes fell somewhere in between. Similarly, with regard to rates of mood disorders, results indicated that the high BPD class had a higher probability of exhibiting mood-related pathology than the baseline class, with the intermediate classes falling between these two groups. Analysis of rates of anxiety disorders across classes indicated that the high BPD class was different from the other three classes (all of which showed comparably low rates). Finally, when examining the association of BPD classes and particular drug dependence categories, our results indicated that the high BPD class had higher rates of cocaine dependence than all other classes and higher rates of alcohol dependence than the baseline and low intermediate classes.

Although findings suggest that the classes reflect four discrete points along a latent continuum of BPD symptom severity, the odds ratios of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders across classes support the premise that the BPD classes are distinct from one another. The differences in rates of co-occurring disorders between high, moderate, and low intermediate classes are especially notable. Compared to the low intermediate class, those in the high BPD class were eight times more likely to meet criteria for an anxiety disorder, and approximately four times more likely to meet criteria for a mood disorder, cocaine dependence, or alcohol dependence. Beyond these differences (which may be expected, given that only 1.2% of the individuals in the low intermediate group met criteria for BPD), there were differences between the high BPD and moderate classes as well. Indeed, those in the high BPD class were almost four times more likely to meet criteria for an anxiety disorder compared to the moderate class. Similarly, those in the high BPD group were more than four times more likely to meet criteria for cocaine dependence than the moderate class. Given the high rate of dysfunction and high representation of individuals meeting criteria for a DSM-IV BPD diagnosis in the moderate class, findings that the high BPD and moderate classes were different on a number of clinical variables are particularly notable. Indeed, these findings highlight the presence of clinically-relevant differences even between two groups with high levels of clinical dysfunction. Further adding to the argument that the moderate class is a distinct and unique class of at-risk individuals, participants in the moderate class were more likely to be diagnosed with mood disorders as well as cocaine and alcohol dependence than members of the baseline class.

Altogether, the findings of this study both provide support for a continuous conceptualization of borderline personality pathology and suggest that individuals at several discrete points along this continuum may differ from one another in clinically-important ways. That is, despite representing different points along the same latent continuum, results suggest that the BPD classes identified here are distinct from one another. As such, findings suggest that there is clinical utility in discretizing the borderline personality pathology continuum into classes, with four (vs. two) classes providing the most useful approach. Indeed, the results of this study suggest that the current diagnostic cutoff both may not fully identify the most at-risk group of individuals and may overlook clinically-important levels of borderline pathology present among individuals represented in the “low intermediate” and “moderate” classes. On the contrary, findings highlight the utility of the LCA system in distinguishing between at-risk groups (even within the group of individuals meeting DSM-IV criteria for a BPD diagnosis), and provide an alternative method of classifying individuals into groups. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have utilized a considerably more stringent assessment of BPD in order to identify a more homogeneous group of individuals with extensive BPD pathology (Zanarini et al., 1989; Zanarini et al., 2002), and extends the research in this area by calling attention to the low intermediate and moderate classes as targets for research, prevention, and intervention efforts. In turn, both lines of research suggest the potential importance of rethinking the DSM-IV diagnosis of BPD, and refining (and potentially restricting) the diagnostic criteria through the use of additional methods (such as LCA) to identify the most high-risk individuals, as well as the less severe but nevertheless “at-risk” and clinically-relevant classes. Such an LCA-based approach to the classification of individuals with varying levels of BP pathology would have important clinical and research implications, suggesting the need to examine the causes, consequences, and clinical correlates of each of the classes identified here (rather than just the presence or absence of a BPD diagnosis), as well as the impact of BPD class on treatment efficacy. Indeed, future research could examine the moderating role of BPD class (e.g., moderate vs. high) on treatments for BPD and related pathology.

Although the current results are interesting and suggest future research endeavors, several methodological limitations should also be noted. First, the current study included a sample of inner-city, predominantly African-American substance users in residential treatment. While this is an underserved and at-risk population, the current findings may not generalize to substance users who are not in residential treatment, do not live in poverty-stricken environments, and are not African-American. Second, the exclusive reliance on self-report measures to assess temperamental vulnerabilities and emotional abuse introduces the potential for biased responding and reporting inaccuracies. As such, future studies should seek to extend this research through the use of behavioral and biological measures of temperamental vulnerabilities and objective measures of abuse. Third, the current study utilized item-level analysis to identify classes. Although this is a useful step in this line of research, future studies may benefit from using continuous (rather than count) measures of BPD that would provide reliability data. Further, the use of continuous measures in identifying classes may help elucidate the clinical differences between the high BPD and intermediate classes. Finally, the current study did not test for the presence of BPD classes based on theoretically-driven underlying constructs (e.g., an “impulsivity” subtype, an “interpersonal difficulties” subtype, etc.), and future work would benefit from addressing this interesting possibility.

Altogether, the current study provides a valuable extension of previous LCA research on BPD, exploring the latent classes of BPD symptoms among a sample of inner-city substance users. Future studies should continue to examine the utility, validity, and generalizability of the 4-class model of BPD pathology identified here. Further, future research should examine the associations between this model and other Axis II pathology, especially given the high rates of co-occurrence between BPD and other personality disorders (Zanarini et al, 1998). Indeed, given our findings of differences between the high BPD and moderate classes on rates of co-occurring Axis I disorders, it is possible that these classes may also differ in rates of co-occurring Axis II disorders - a finding with important clinical implications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant R36 DA021820 awarded to the first author. The NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors also thank Walter Askew of the Salvation Army Harbor Lights Residential Treatment Center of Washington DC for assistance in subject recruitment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/pas.

Contributor Information

Marina A. Bornovalova, Center for Addictions, Personality, and Emotion Research and the University of Maryland

Roy Levy, Division of Psychology in Education, Arizona State University.

Kim L. Gratz, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

C. W. Lejuez, Center for Addictions, Personality, and Emotion Research and the University of Maryland

References

- Agrawal HR, Gunderson J, Holmes BM, Lyons-Ruth K. Attachment studies with borderline patients: A review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2004;12:94–104. doi: 10.1080/10673220490447218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: APA; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Handelsman L. Predicting personality pathology among adult patients with substance use disorders: effects of childhood maltreatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;6:855–868. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohus M, Limberger U, Ebner FX, Glocker B. Pain perception during self-reported distress and calmness in patients with borderline personality disorder and self-mutilating behavior. Psychiatry Research. 2000;95:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Nick B, Delaney-Brumsey A, Lynch TR, Kosson D, Lejuez CW. A multimodal assessment of the relationship between emotion dysregulation and borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users in residential treatment. Journal of Psychiatry Research. 2007;12 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Delaney-Brumsey A, Paulson A, Lejuez CW. Temperamental and environmental risk factors for borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users in residential treatment. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20:218–31. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce SC, Coccaro E. Factors differentiating personality-disordered individuals with and without a history of unipolar mood disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 1999;10:147–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas A, Clark LA. Dependency, impulsivity, and self-harm: Traits hypothesized to underlie the association between cluster B personality and substance use disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:424–436. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.5.424.22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin JF, Widiger TA, Frances AJ, Hurt SW, Gilmore M. Prototypic typology and the borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92:263–275. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin JF, Hull JW, Hurt SW. Factor structure of borderline personality disorder criteria. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton A, Pilkonis P. Evidence for a single latent class of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders borderline personality pathology. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2007;48:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti FJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Loo CM, Giles WH. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse neglect and household dysfunction. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubo ED, Zanarini MC, Lewis RE, Williams AA. Childhood antecedents of self-destructiveness in borderline personality disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42:63–69. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Pearson PR, Easting G, Allsopp JF. Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness, and empathy in adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders: Non-patient edition (SCID-NP, v. 2.0) New York: NY State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J, Mullen PE, Sibthorpe B, Attewell R, Bammer G. The relationship between childhood sexual abuse and alcohol abuse in women: A case control study. Addiction. 1998;93:1787–1798. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931217875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, Luckey JW, Brown BS, Hoffman JA, Dunteman GH, Theisen AC, Hubbard RL, Needle R, Schneider SJ, Koman JJ, et al. Relationship between drug preference and indicators of psychiatric impairment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21:153–166. doi: 10.3109/00952999509002685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Maffei C, Bagnato M, Donati D, Namia C, Novella L. Latent structure analysis of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40:72–79. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyer MR, Frances AJ, Sullivan T, Hurt SW, Clarkin J. Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:348–352. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800280060008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG. The borderline’s disturbed relationships as a phenotype: Evidence, possible endophenotypes, and implications. 2005 Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, Daversa MT, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Zanarini MC, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Yen S, Sanislow CA, Bender DS, Dyck IR, Morey LC, Stout RL. Predictors of 2-Year Outcome for Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:822–826. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JA, Klein H, Eber M, Crosby H. Frequency and intensity of crack use as predictors of women’s involvement in HIV related sexual risk behaviors. Drug and Alcohol Dependance. 2000;58:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski JL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. Childhood physical and sexual abuse as risk factors for heavy drinking among African-American women: A prospective study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2000;24:1061–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than nondrug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks B, Patrick CJ, Carlson S, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld PF, Henry NW. Latent Structure Analysis. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Daughters SB, Curtin JJ. Differences in impulsivity and sexual risk behavior among inner-city crack/cocaine users and heroin users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;77:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, Richards JB, Ramsey SE, Stuart GL, Strong DR, Brown RA. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk-taking: The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2002;8:75–84. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.8.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Schmidt H, Dimeff LA, Craft JC, Kanter J, Comtois KA. Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug-dependence. American Journal of Addictions. 1999;8:279–292. doi: 10.1080/105504999305686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, Jackson DN, Schroeder ML. Factorial structure of traits delineating personality disorders in clinical and general population samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:432–40. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:941–948. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Colder CR. The UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:1927–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Masyn KE. The consequences of (latent) classes: Results of a simulation study evaluating approaches to specifying and testing the effects of latent class membership on distal outcomes. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association; San Diego, CA. April, 2009.2009. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AC. Latent class analysis. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102:256–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: Baseline Axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatra Scandavia. 2000;102:256–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite mixture models. New York: John Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Medrano MA, Hatch JP, Zule WA, Desmond DP. Psychological distress in childhood trauma survivors who abuse drugs. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:1–13. doi: 10.1081/ada-120001278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Personality disorders under DSM-III and DSM-III-R: An examination of convergence, coverage, and internal consistency. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145:573–577. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Gunderson JG, Quigley BD, Shea MT, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, Stout RL, Zanarini MC. The Representation of Borderline, Avoidant, Obsessive-Compulsive, and Schizotypal Personality Disorders by the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:215–234. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.215.22541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 4. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund-Gibson KL. Covariates and mixture modeling: Results of a simulation study exploring the impact of misspecified covariate effects. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association; San Diego, CA. April, 2009.2009. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Curtin JJ, Tellegen A. Development and validation of a brief form of the multidimensional personality questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:150–163. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Daza N, Weeks M, Singer M. “Nobody Gives a Damn if I Live or Die”: Violence, Drugs, and Street-Level Prostitution in Inner-City Hartford, Connecticut. Medical Anthropology. 2003;22:233–259. doi: 10.1080/01459740306770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Hwang LY, Zack C, Bull L, Williams ML. Sexual risk behaviors and STIs in drug abuse treatment populations whose drug of choice is crack cocaine. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2002;13:769–774. doi: 10.1258/095646202320753736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Newman E, Pelcovitz D, van der Kolk B, Mandel FS. Complex PTSD in victims exposed to sexual and physical abuse: results from the DSM-IV field trial for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:539–555. doi: 10.1023/a:1024837617768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild L, Cleland C, Haslam N, Zimmerman MA. Taxometric Study of Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:657–666. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclove L. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin M, Dorahy M, Adamson G, Murphy J. Subtypes of borderline personality disorder, associated clinical disorders and stressful life-events: a latent class analysis based on the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;46:273–81. doi: 10.1348/014466506x150291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siever LJ, Davis KL. A psychobiological perspective on the personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1647–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siever LJ, Torgersen S, Gunderson JG, Livesley WJ, Kendler KS. The borderline diagnosis III: identifying endophenotypes for genetic studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:964–968. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O’Brien M, Lee A, Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000. London: Stationery Office; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Hyler SE, Stein DJ, Hollander E, Gallagher PE, Lopez AE. Patterns of anxiety and personality disorder comorbidity. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1995;29:361–374. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(95)00015-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, Siever LJ. The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personaltity structure. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:936–950. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Siever LJ, Livesley WJ, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA. The borderline diagnosis II: biology, genetics, and clinical course. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:951–963. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First . Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-III-R (SCID_II) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV--Non-Patient Edition (SCID--NP, Version 2.0) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Unpublished manuscript. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis: 1982. Brief manual for the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher DL, Cornelius JR, Clark DB. Adolescent alcohol use disorders predict adult borderline personality. Addictive Behaviours. 2005;30:1709–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, Durbin J, Burr R. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders. A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:235–253. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Lynam DR, Costa PT. Borderline personality disorder from the perspective of general personality functioning. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:193–202. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five-Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wilberg T, Urnes O, Friis S, Pedersen G, Karterud S. Borderline and avoidant personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality: A comparison between DSM-IV diagnoses and NEO-PI-R. Journal of personality disorders. 1999;13:226–240. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1999.13.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Swift WJ. Borderline versus other personality disorders in the eating disorders: Clinical description. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1990;9:629–638. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, et al. Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1733–1739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Pathways to the development of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1997;11:93–104. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: Discriminating BPD from other Axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini M, Frankenburg F, Dubo E, Sickel A, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V. Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39:296–302. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Axis I diagnostic comorbidity and borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40:245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]