Abstract

The off-line coupling of an isoelectric trapping device termed membrane separated wells for isoelectric focusing and trapping (MSWIFT) to mass spectrometry-based proteomic studies is described. The MSWIFT is a high capacity, high-throughput, mass spectrometry compatible, isoelectric trapping device that provides isoelectric point (pI) based separations of complex mixtures of peptides. In MSWIFT, separation and analyte trapping are achieved by migrating the peptide ions through membranes having fixed pH values until the peptide pI is bracketed by the pH values of adjacent membranes. The pH values of the membranes can be tuned, thus affording a high degree of experimental flexibility. Specific advantages of using MSWIFT for sample pre-fractionation include: (i) small sample volumes (~200 μl), (ii) customized membranes over a large pH range, (iii) flexibility in the number of desired fractions, (iv) membrane compatibility with a variety of solvents systems and (v) resulting fractions do not require sample cleanup prior to MS analysis. Here, we demonstrate the utility of MSWIFT for mass spectrometry-based detection of peptides in improving dynamic range and the reduction of ion suppression effects for high-throughput separations of tryptic peptides.

Introduction

Sample pre-fractionation techniques are widely used to decrease the complexity of proteomic samples prior to liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis [1]. The use of isoelectric focusing (IEF) to separate ampholytic compounds such as peptides or proteins based on differences in isoelectric point (pI) [2, 3] is becoming increasingly useful for many different types of mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics [4–6]. Early MS-based proteomics utilized two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D-GE); [7, 8] however, IEF also can be achieved in gel matrices, capillaries, and multi-compartment electrolyzers (MCE’s). Although considerable improvements have been made in 2D-GE, [9–11] there are significant problems associated with the technology [12], specifically 2D-GE performs poorly for very large and small proteins, hydrophobic proteins, and proteins with extremely acidic or basic pI values. Furthermore, proteomic studies based on the coupling of gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry is labor intensive. To circumvent these limitations, alternative IEF methods such as analytical scale MCE’s have been developed and combined successfully with MS for proteomic applications [6, 13–19]. Pre-fractionation devices based on solution IEF enhance several key aspects of the analysis, e.g., (i) they increase the dynamic range owing to a partitioning of high and low abundance species across multiple fractions and (ii) increase the sample loading capability because analyte incorporation into a gel matrix is not required. In addition, separations can be performed in a few hours and analytes are captured and retained in the solution phase [20]. On the other hand, a significant limitation of solution IEF is the increased sample handling required to remove carrier ampholytes prior to MS analysis.

An alternative carrier ampholyte-free pI-based separation method called isoelectric trapping (IET) has been described [13, 21, 22]. IET uses buffering membranes to create a step-wise pH gradient, thereby establishing a series of separation wells bracketed by membranes with well-defined pH values. In IET, proteins or peptides migrate under the influence of an electric field until the individual components reach a compartment in which the pH values of the buffering membranes bracket the pI value of the analyte. In order to reduce protein precipitation, which can occur near or at the isoelectric point [23], the individual compartments can be buffered using small ampholytic molecules, e.g., amino acids [24]. These buffering molecules do not interfere with MS analysis such as matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) owing to their low molecular weights which fall below the m/z range of interest.

Lim and coworkers developed an IET device termed membrane separated wells for isoelectric focusing and trapping (MSWIFT) [25]. The primary advantages of the MSWIFT device for MS-based proteomics include (i) small volumes wells (~200 μl), (ii) tunable membranes that cover a wide pH range (pH 2–12), (iii) option for a large number of fractions, (iv) absence of sample cleanup after IET and (v) membrane compatibility with both aqueous and organic solvent systems. They demonstrated the utility of MSWIFT for separation and concentration of ampholytes while minimizing the detrimental effects associated with fast electrophoretic techniques, i.e., Joule heating and sample overloading. Preliminary experiments from their work include demonstration of desalting capabilities, enrichment of a minor component from a synthetic mixture and fractionation of egg white proteins, which has implications for proteomics experiments. For comparison, one of the most highly utilized pI-based separation devices for proteomic studies is the OFFGEL™ Fractionator (Agilent Technologies). Much of the work on the OFFGEL™ device has been centered on peptide separations followed by MS analysis. Samples including cerebral spinal fluid [26], brain tissue [27] and yeast [28, 29] have been analyzed and quantitative studies incorporating iTRAQ labeling have been reported [30, 31]. The OFFGEL™ is an attractive method for peptide fractionation considering its multi-plexing abilities - running several strips simultaneously, small sample volume and low sample quantity requirements. However, several inherent limitations are associated with the technology such as long separation times, sample cleanup requirements, the need for an insulated cooling system and a lack in the ability to customize the number of wells or pH ranges. These restrictions however, are not associated with using the MSWIFT device. Several proof-of-concept experiments, specifically focused on bottom-up proteomics are included here to illustrate the compatibility and advantages of using MSWIFT as a pre-fractionation device for mass spectrometry-based studies.

Experimental

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless noted otherwise. HPLC grade acetonitrile was purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ). Peptide standards from American Peptide Company (Sunnyvale, CA) were used without further purification. All experiments were performed using purified 18 M water (Barnstead International, Dubuque, IA).

MSWIFT and IET

MSWIFT

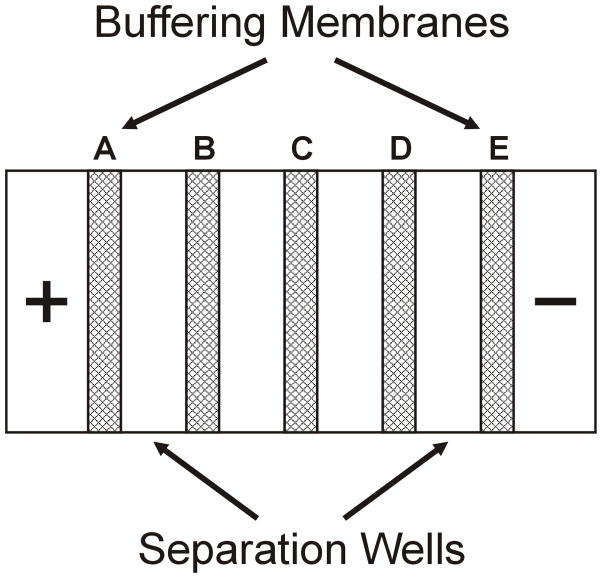

The design and assembly of MSWIFT have been previously described [25, 32]. Briefly, the main housing of MSWIFT was built using polycarbonate and equipped with an aluminum heat sink. Poly(vinyl-alcohol) based buffering membranes with tunable pH values were synthesized in-house [33–36]. A schematic of the MSWIFT assembly is displayed in Figure 1. Features include the anode and cathode compartments, variable number of separation wells and buffering membranes (labeled A–E from low to high pH values in Figure 1). A detailed AutoCAD drawing of the device is provided in the supplementary material section (Figure S1) and includes the details related to each component.

Figure 1.

Schematic of MSWIFT assembly including anode/cathode compartments, separation wells and buffering membranes. The four compartment setup was used to separate a mixture of five standard peptides followed by MALDI-MS analysis. The pH values of the buffering membranes used were: 2.9 (A), 5.4 (B), 7.6 (C), 9.0 (D) and 11.0 (E). This configuration would allow for each peptide to be trapped into a single separation well with the exception of angiotensin I & II peptides which are trapped together in the second separation well. A similar configuration was used in all other experiments, except the number of separation wells and the pH values of the buffering membranes were tailored to each separation.

IET

Alumina separation wells were assembled serially and buffering membranes were inserted into silicone pouches in between each well. The wells were filled with 200μL of either the peptide sample solution and/or an ampholytic buffer. The anode solution was 3 mM methanesulfonic acid, and the cathode solution was 3 mM sodium hydroxide. Compartment solutions were pH biased by ampholytic buffers as previously described [24]. Typical separation times ranged from 45–60 minutes at 5W constant power. Theoretical pI values were calculated using the compute pI/MW tool from ExPASy [37].

IET of a five-peptide mixture

The five peptides, leptin (93–105) (NVIQISNDLENLR, pI 4.4), angiotensin I (DRVYIHPFHL, pI 6.9), angiotensin II (DRVYIHPF, pI 6.7), angiotensin III (RVYIHPF, pI 8.8) and bradykinin fragment 1-7 (RPPGFSP, pI 9.8) were mixed to final concentrations of 0.05 mg mL−1 for leptin and bradykinin and 0.025 mg mL−1 for the angiotensin peptides. The pH values of the five buffering membranes were 2.9, 5.4, 7.6, 9.0 and 11.0. The peptide mixture was loaded in the fourth separation well bracketed by pH 9.0 and 12.0 membranes then separated. After fractionation, an aliquot from each separation well was analyzed using MALDI-MS.

Proteolytic digestion and IET of a five-protein mixture

A protein mixture containing bovine α-casein, bovine serum albumin, bovine apo-transferrin, bovine ribonuclease A and horse cytochrome c (10 μg each) was prepared in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer, pH 8. The protein mixture was reduced by adding dithiothreitol to a final concentration of 5 mM followed by incubation at 60 °C for 1 hour. Alkylation was performed by adding methane methylthiosulfonate (MMTS) (20 mM final concentration) and the solution was incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Trypsin (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) was added at an enzyme to protein ratio of 1:50 (w/w) and digestion was carried out at 37 °C overnight. The resulting peptides were loaded into the second separation well of MSWIFT (bracketed by pH 4.5–5.4 membranes) and subjected to IET separation. The pH values of all the membranes were as follows: 2.0, 4.5, 5.4, 6.5, 7.6, 8.2 and 12.0. Following separation, MALDI-MS analysis was performed using an aliquot obtained from each fraction.

Proteolytic Digestion, IET and LC-MS/MS analysis of yeast lysate

Soluble yeast proteins (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) were prepared in 100 mM 3-morpholinopropane sulfonic acid (MOPS), 100 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) with protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford Assay [38]. A total of 180 μg of protein was reduced using tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine at a final concentration of 5 mM and incubated at 60 °C for 1 hour. Alkylation using MMTS and trypsin digestion were carried out as outlined for the five-protein mixture. The pH values of the membranes were as follows: 2.0, 4.7, 5.4, 6.5, 7.0, 8.2 and 12.0. The sample was loaded in the fourth separation well (bracketed by pH 6.5–7.0 membranes) and IET was carried out. Following separation, an aliquot from each compartment solution was subjected to reversed phase liquid chromatography (LC), coupled offline to MALDI-MS/MS analysis via a robotic spotting device as previously described [39]. In the two-stage MSWIFT separation of yeast peptides, an additional 200 μg of yeast was digested as above and fractionated. The pH values of the buffering membranes were: 2.9, 4.0, 5.4, 6.8, 7.5, 9.8 and 11.0 (1st stage) and 4.0, 4.5, 5.0 and 5.4 (2nd stage). An aliquot of the contents of the pH 4.0–5.4 well in the first dimension separation were analyzed using LC-MS/MS then the remaining solution was subjected to further IET fractionation followed by LC-MS/MS analysis.

MALDI – MS and Database Searching

Samples (excluding yeast) were mixed 1:1 (v/v) with the MALDI matrix (5 mg mL−1 α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, 50% (v/v) acetonitrile, 10 mM ammonium dihydrogen phosphate, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) and 1 μL of the resulting mixture was spotted onto a MALDI target. MALDI mass spectra were acquired using either a Voyager DE-STR, Model 4700 or 4800 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA). Collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra were acquired using air as the collision gas (medium pressure setting) and at 1 kV of collision energy. Tandem MS data collected for the five-protein mixture and yeast lysate experiments were analyzed using the GPS Explorer Software (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) and an in-house license of the search engine MASCOT (v. 2.1) [40]. The five-protein mixture data were searched against the Swiss-Prot database with the following search parameters: taxonomy, metazoa; enzyme, trypsin; missed cleavages, 1; variable modifications, oxidation (M) and MMTS (C). Data collected from the yeast separation experiment were searched against the Saccharomyces Genome Database (www.yeastgenome.org, downloaded March 4, 2010, 6717 sequences) with the following parameters: precursor tolerance, 100 ppm; fragment ion tolerance, 0.8Da; enzyme: trypsin; missed cleavages, 1; and variable modifications, oxidation (M) and MMTS (C). Protein assignments were made using a minimum of two peptides and a score of 21 (p<0.05) determined by MASCOT. For reference, we have provided a table of the top 989 protein assignments (99.990% confidence interval, 2 peptide minimum) which includes the 593 identifications obtained from the MASCOT search (Table S3). The same criteria were used for protein identifications in the two-stage separation experiment. Data reporting peptide assignments (two-stage experiment) included all matched peptides without implementing an ion score cut-off.

Results and Discussion

Lim and coworkers previously reported proof-of-concept analyte fractionation experiments for a variety of different analytes, ranging from small molecules to egg white proteins. Here, we focus on developing applications of MSWIFT-MALDI-MS for protein identification using ‘bottom-up’ techniques. For example, MSWIFT provides an ideal option for bottom-up proteomics for peptide-based fractionation followed by MS, MS/MS and/or reversed phase LC-MS/MS analysis owing to the flexibility in arrangement and operation of the device. Oftentimes, the analysis of minor components or even major components that do not ionize well by MALDI or ESI in complex mixtures is severely limited, and a rapid, reproducible fractionation technique can be used to circumvent such problems. Several proof-of-concept experiments, specifically focused on bottom-up proteomics are included to illustrate the compatibility and advantages of using MSWIFT as a pre-fractionation device.

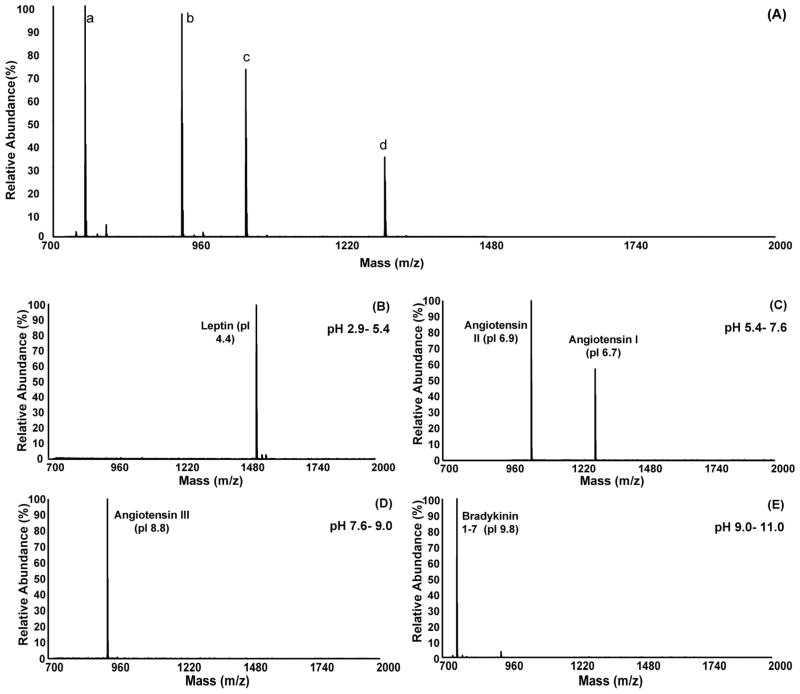

Fractionating a mixture of peptides having very different pI values illustrates the basic operation of the device. A mixture composed of five standard peptides, leptin (pI 4.4), angiotensin II (pI 6.7), angiotensin I (pI 6.9), angiotensin III (pI 8.8) and bradykinin 1-7 (pI 9.8) was analyzed using MALDI-MS before and after fractionation (Figure 2). Note, however, that a signal for the [M + H]+ ion of leptin (m/z 1527.81) is not observed in the MALDI spectrum of the mixture (Figure 2A), possibly owing to analyte suppression effects [41]. This same peptide mixture was then fractionated using MSWIFT under conditions where individual peptides should be trapped in wells in which buffering membranes bracket the pI value of each peptide (see Figure 1). The pI values for angiotensin II and angiotensin I peptides are similar (6.7 and 6.9, respectively) thus these two peptides should be trapped in the same compartment. Following fractionation, an aliquot from each fraction was analyzed by MALDI-MS. Figure 2(B–E) contains the MALDI mass spectra for each of the wells which are defined by pH buffering membranes: pH 2.9–5.4 (2B), pH 5.4–7.6 (2C), pH 7.6–9.0 (2D) and pH 9.0–12.0 (2E). Each of the standard peptides is observed in the predicted well based on the calculated pI values of the peptides and the pH values of the buffering membranes used. In Figure 2E (pH 9.0–12.0), a low abundance signal (< 5% relative abundance to the bradykinin signal) at m/z 931.68 is also observed and corresponds to the [M + H]+ ion of angiotensin III (pI 8.8), which may indicate a slightly insufficient electrophoresis time. On the basis of these experiments we conclude that the MSWIFT device is capable of separating ampholytic components (i.e., peptides) where the resulting fractions can be analyzed using MALDI-MS. Peptides are trapped according to their pI values and experimental results are in agreement with theoretical pI calculations. Additional signals, (i.e., leptin) are observed following fractionation highlighting an advantage to using this device and technique.

Figure 2.

MALDI mass spectrum of a mixture of five peptides before and after IET separation. (A) MALDI mass spectrum of the peptide mixture prior to separation using the MSWIFT device. The mixture contains (a) Bradykinin 1–7 (pI 9.8, [M+H]+obs = 757.39 Da), (b) Angiotensin III (pI 8.8, [M+H]+ obs = 931.54 Da), (c), Angiotensin I (pI 6.9, [M+H]+obs = 1296.75 Da), (d) Angiotensin II (pI 6.7, [M+H]+obs = 1046.58 Da). Each ion signal is labeled with the appropriate peptide with the exception of Leptin (pI 4.4, [M+H]+calc = 1527.81 Da) which is not observed. (B–E) MALDI mass spectra taken from an aliquot of each separation well following IET using MSWIFT. The pH values of the buffering membranes used are indicated in each spectrum. Peptide ion signals are labeled as follows: Bradykinin 1–7 (pI 9.8, [M+H]+ obs = 757.50 Da), Angiotensin III (pI 8.8, [M+H]+obs = 931.66 Da), Angiotensin I (pI 6.9, [M+H]+obs = 1296.88 Da), Angiotensin II (pI 6.7, [M+H]+obs = 1046.68 Da), Leptin (pI 4.4, [M+H]+obs = 1527.99 Da).

IET-MS of complex mixtures

Separation of a five-protein tryptic digest

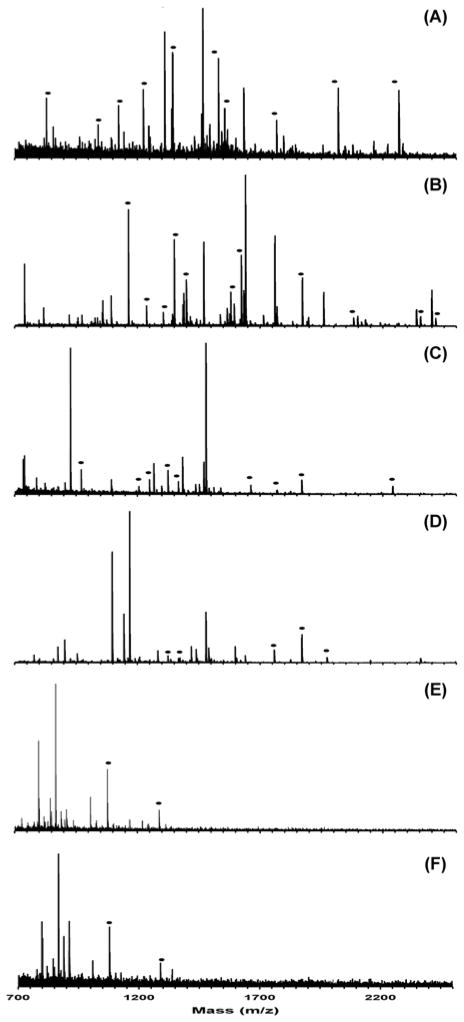

To demonstrate MSWIFT separation/IET of more complex samples, a solution obtained by the proteolytic digestion of a mixture of five proteins: α-casein, albumin, apo-transferrin, ribonuclease A, and cytochrome c was analyzed. In silico digestion of this five-protein mixture yields a mixture of 345 possible peptides with molecular weights ranging from 500–4500 Da, assuming a single missed-cleavage. The MALDI mass spectra obtained from an aliquot of each fraction following the IET separation is shown in Figure 3(A–F). Inspection of the six resulting mass spectra display varying ion signal patterns which indicates that the peptides present in each separation well differ from each other. Note that numerous ion signals that are observed following IET are not observed in the non-fractionated samples, and are denoted with filled circles (●). The peptides observed from the five-protein mixture digest generally have theoretical pI values that fall within the pH values of the buffering membranes used in their respective separation wells, which verifies that MSWIFT is trapping the ampholytic components as it should. For example, the signal at m/z 1871.95 in the well bracketed by pH 4.5 and 5.4 buffering membranes (Figure 3B) corresponds to the theoretical m/z of the αs1-casein peptide at residues 119-134 (YKVPQLEIVPNSAEER). A MASCOT database search performed on the six post-fractionation spectra results in the identification of four out of five proteins at the >99.990% confidence interval. Ribonuclease A, which is not identified from database searching, has very few tryptic cleavage sites (13 R or K residues), thus a limited number of tryptic peptides are observed. Low abundance ion signals corresponding to ribonuclease A peptides are observed but were not selected for fragmentation by the automated software. By manual inspection of the mass spectrum obtained from the well bracketed by pH 6.5 and 7.6 membranes, the signals observed at m/z 2353.87 and 2495.12 can be assigned to tryptic ribonuclease A fragments 37-57 (QHMDSSTSAASSSNYCNQMMK, [M+H]+calc-2353.91 Da) and 66-87 (CKPVNTFVHESLADVQAVCSQK, [M+H]+calc - 2495.18 Da), respectively. The theoretical pI value calculated for both of these peptides is 6.7, which falls between the pH values of the buffering membranes. Therefore, the protein can be assigned with increased confidence based on accurate mass and peptide pI [42].

Figure 3.

(A–F). MALDI mass spectrum of the contents of each MSWIFT separation well from the IET separation of the five protein digestion mixture. The mixture includes tryptic peptides from the proteins bovine serum albumin, apo-transferrin, ribonuclease A, αs1-casein, and cytochrome c. The pH values of the buffering membranes used were as follows: (1) pH 2.0–4.5, (2) pH 4.5–5.4, (3) pH 5.4–6.5, (4) pH 6.5–7.6, (5) pH 7.6–8.2 and (6) pH 8.2–12.0. Peptide ion signals denoted with a filled circle (●) are those which are not observed in the mass spectrum acquired prior to IET separation.

The amino acid sequence coverage values obtained for the four proteins identified by database searching using only tandem MS data acquired after MSWIFT fractionation are as follows: albumin – 20%, apo-transferrin – 24%, cytochrome c – 58% and αs1-casein – 28%. The amino acid sequence coverage of these proteins may be low owing to the limited number of tandem MS spectra acquired for each MALDI spot based on software settings and prior to sample consumption. For comparison, MS/MS analysis of a tryptic digest of the five-protein mixture without fractionation results in the following sequence coverage values: albumin – 18%, apo-transferrin – 13%, cytochrome c – 26% and αs1-casein – 26%. Most notable are the increases for cytochrome c (32%) and apo-transferrin (11%) observed with fractionation. A more significant increase in amino acid sequence coverage would be observed given additional IET experiments or analyzing each fraction using LC-MS/MS. However, the goal of this work does not encompass maximizing the coverage for a standard mixture. Note that the majority of peptide ion signals are observed from fractions taken from the first three separation wells (pI values 2.0–7.6) and very few signals are observed in the most basic wells. This trend observed from the five-protein mixture digest is also observed by plotting the calculated peptide molecular weight versus theoretical pI for the in silico digestion of bovine serum albumin where 74% of the tryptic peptides have pI values less than 7.6 (data not shown). Separating the five-protein digestion mixture illustrates the ability of MSWIFT to provide initial fractionation after which the resulting fractions can be analyzed using MALDI-MS. However, more sophisticated techniques such as LC or additional IET separations are needed for the analysis of more complex mixtures.

Analysis of a Yeast Protein Digest

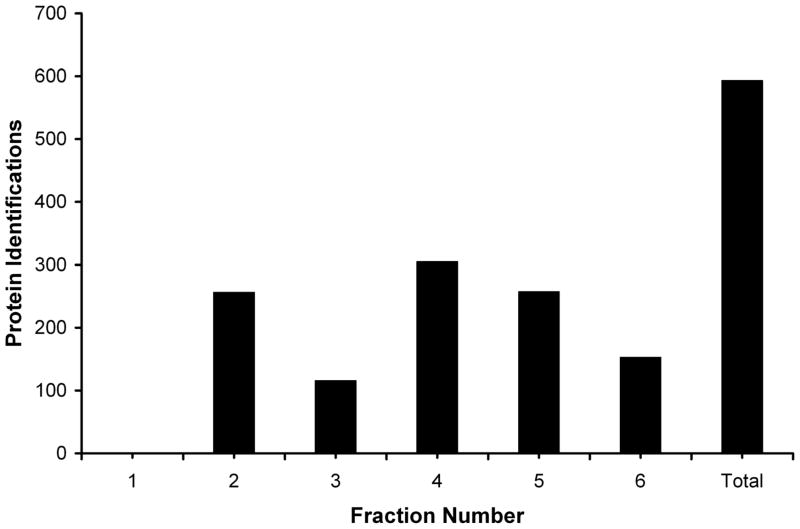

Successful analysis of complex mixtures typically relies on two separation techniques. When the separation principles of the two techniques are different, they are considered orthogonal, and the resulting separation or peak capacity is maximized. Therefore, fractions obtained from MSWIFT which have been separated based on pI, can be further separated using techniques such as capillary electrophoresis or LC. To illustrate this, we chose to separate and analyze the tryptic peptides from soluble S. cerevisiae proteins. Tryptic peptides were first subjected to IET separation using MSWIFT, followed by reversed phase LC-MS/MS analysis of the contents of each MSWIFT separation well. From database searching, 593 proteins were identified from a single analysis with high confidence. Similarly, Yates and coworkers successfully identified yeast proteins by separating peptides using strong cation exchange and reversed phase LC-MS/MS known as the MudPIT approach [43]. Haynes et al. analyzed yeast proteins using a variety of separation techniques including strong cation exchange and reversed phase chromatography as well as electrophoretic methods (i.e., SDS-PAGE, IEF) [44]. Analysis of our data indicates that fractionation was successful as observed in Figure 4 where the number of unique protein assignments from each fraction is plotted as well as the total number unique protein identifications in the last column. The breakdown of the number of protein identifications by fraction is: 0 (pH 2.0–4.7), 256 (pH 4.7–5.4), 116 (pH 5.4–6.5), 305 (pH 6.5–7.0), 257 (pH 7.0–8.2), 153 (pH 8.2–12.0) and 593 combined. The analysis of proteins with high and low values of pI or MW is not compromised using the MSWIFT device and LC-MS/MS in a bottom-up approach. For example, Stress Protein DDR48 and 60S Ribosomal Protein L19A were both identified and have calculated pI values of 4.22 and 11.35 respectively. Furthermore, protein size is not problematic since peptides are being fractionated. For example, the 245kD protein URA2 and 12kD Heat Shock Protein were both identified. An additional benefit is the amount of material that was loaded. Compared to gel-based methods, there is no limit to the amount of sample that can be fractionated. Although our experiment utilizes 180 μg, much larger amounts (i.e., mg scale) could easily be fractionated as was demonstrated in early experiments [25]. Furthermore, using this experimental scheme allows incorporation of pI for low scoring peptides to improve confidence in assignment. Take for example the peptide, 85IDSVIHFAGLK95 from the protein UDP-glucose-4-epimerase (GAL10). Based on tandem MS data, and a MASCOT score of 15, peptide assignment may not be regarded as highly confident. However, considering that the peptide has a theoretical pI value of 6.7 and is observed in the pH 6.5–7.0 well, increases the confidence in the peptide assignment [45]. Utilizing pI to improve peptide assignment may not always be feasible because the theoretical pI value is for an aqueous environment assuming that all residues are exposed and does not account for peptide or protein structure. Nevertheless, in cases such as the above example, pI clearly assists in the peptide assignment.

Figure 4.

Plot of the number of unique proteins identified in each fraction of the MSWIFT. The final column represents the total number of proteins identified by database searching tandem MS data obtained from all six fractions.

Another feature of the MSWIFT device is the ability to fractionate a sample multiple times. To demonstrate the utility of multi-stage separation experiments, we fractionated tryptic peptides from yeast into six fractions. Based on manual inspection of the MALDI mass spectrum taken of each fraction, the second well (pH 4.0–5.4) looked the most complex; this assumption is supported by earlier studies for Escherichia coli tryptic peptides [46]. Following initial fractionation, an aliquot of the contents of the pH 4.0–5.4 well was analyzed using LC-MS/MS and the remaining solution was then fractionated a second time using MSWIFT into three additional wells (pH 4.0–4.5, pH 4.5–5.0 and pH 5.0–5.4). The contents of the three wells from the second stage were also analyzed using LC-MS/MS. Preliminary data from this experiment results in 696 peptides identified corresponding to 155 protein identifications from the first dimension of separation. Following a second stage of fractionation, the combined LC-MS/MS data resulted in an approximate two-fold increase in the number of identified peptides to 1436 corresponding to 231 protein identifications. The LC-MS/MS data obtained from each of the three wells in the second stage of fractionation was also subjected to database searching and the number of peptides and protein assignments are provided in Table S2. The greatest number of peptide and protein identifications (813 peptides and 203 proteins) from the second stage separation was observed in the pH 4.5–5.0 fraction. Manual inspection of the preliminary data suggests that the majority of peptides are observed in their proper well and very few peptides are being assigned in multiple wells which serve an additional indicator that MSWIFT works as an efficient pI-based separation device. Utilizing a multi-stage separation scheme increases the ability to identify low abundance proteins in the presence of highly abundant proteins. An example from these data is the identified proteins proteinase B which is known to be present at 1600 copies per cell and pyruvate kinase which is present at 291,000 copies per cell (www.yeastgenome.org). These results suggest that in order to identify low abundance proteins and peptides, fractionation is essential and the ability to perform several dimensions of fractionation followed by LC-MS/MS analysis greatly increases the number of peptides that can be identified. In turn, the number of protein identifications will increase as well as the confidence in protein assignment.

Conclusions

The utility of MSWIFT for fractionation of peptides on the basis of pI followed by MALDI-MS and LC-MS/MS analysis is demonstrated for both model peptide mixtures and for the analysis of a complex proteome (yeast lysate). Amino acid sequence coverage values obtained for peptide mass mapping and tandem MS are typically higher following fractionation compared to direct analysis of the mixture. For example, numerous peptide ion signals which are not observed in crude mixtures are observed following MSWIFT fractionation. We have successfully used MSWIFT for a large scale proteomic analysis by separating tryptic peptides from yeast followed by LC-MS/MS and demonstrated that several hundred proteins can be assigned from a single analysis and that the number of peptide identifications is distributed throughout the MSWIFT fractions. Peptides with low MASCOT scores can be assigned with increased confidence when theoretical pI values fall between the pH values of the buffering membranes. Finally, we have performed initial experiments showing the ability to carry out multiple separations on a single sample by taking a first stage fraction and further fractionating the contents. By implementing a two-stage MSWIFT separation strategy, the number of peptide and protein identifications increased. Further experiments are currently underway investigating multi-stage separations using the MSWIFT device to increase the depth of proteome coverage. These proof-of-concept experiments illustrate the utility of MSWIFT as a high-throughput device that provides flexibility, increased sample load capacity and eliminates the need for sample clean-up for mass spectrometry-based proteomic studies.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. AutoCAD drawing of the MSWIFT separation device. All major features of the MSWIFT are illustrated. Specific details outlining the construction and assembly of the MSWIFT device have been previously described [25, 32]

Table S2. Summary of the number of proteins and peptides assigned from the two-stage fractionation of yeast tryptic peptides. For comparison the results from performing only one-stage of fractionation is included in the first column. Using the two-stage separation scheme clearly increases the number of peptides and protein assignments.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by U. S. Department of Energy, Division of Chemical Sciences, Basic Energy Sciences (BES DE-FG02-04ER15520), Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources (1 S10 RR022378-01) and the Office of Vice-President for Research, Texas A&M University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Righetti PG, Castagna A, Herbert B, Reymond F, Rossier JS. Prefractionation Techniques in Proteome Analysis. Proteomics. 2003;3:1397–1407. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolin A. Separation and Concentration of Proteins in a Ph Field Combined with an Electric Field. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1954;22:1628–1629. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svensson H. Isoelectric Fractionation, Analysis, and Characterization of Ampholytes in Natural Ph Gradients. 1. Differential Equation of Solute Concentrations at a Steady State and Its Solution for Simple Cases. Acta Chemica Scandinavica. 1961;15:325–341. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gygi SP, Corthals GL, Zhang Y, Rochon Y, Aebersold R. Evaluation of Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis-Based Proteome Analysis Technology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:9390–9395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160270797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen PK, Pasa-Tolic L, Anderson GA, Horner JA, Lipton MS, Bruce JE, Smith RD. Probing Proteomes Using Capillary Isoelectric Focusing-Electrospray Ionization Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1999;71:2076–2084. doi: 10.1021/ac990196p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heller M, Michel P, Morier P, Crettaz D, Wenz C, Tissot JD, Reymond F, Rossier JS. Two Stage Off-Gel Isoelectric Focusing: Protein Followed by Peptide Fractionation and Application to Proteome Analysis of Human Plasma. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:1174–1188. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Righetti PG, Bossi A, Wenisch E, Orsini G. Protein Purification in Multicompartment Electrolyzers with Isoelectric Membranes. Journal of Chromatography B. 1997;699:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Righetti PG, Bossi A. Isoelectric Focusing of Proteins and Peptides in Gel Slabs and in Capillaries. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1998;372:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson L, Anderson NG. High-Resolution 2-Dimensional Electrophoresis of Human-Plasma Proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1977;74:5421–5425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson NL, Anderson NG. A 2-Dimensional Gel Database of Human Plasma-Proteins. Electrophoresis. 1991;12:883–906. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150121108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henzel WJ, Billeci TM, Stults JT, Wong SC, Grimley C, Watanabe C. Identifying Proteins from 2-Dimensional Gels by Molecular Mass Searching of Peptide-Fragments in Protein-Sequence Databases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:5011–5015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorg A, Weiss W, Dunn MJ. Current Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis Technology for Proteomics. Proteomics. 2004;4:3665–3685. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Righetti PG, Barzaghi B, Luzzana M, Manfredi G, Faupel M. A Horizontal Apparatus for Isoelectric Protein-Purification in a Segmented Immobilized Ph Gradient. Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods. 1987;15:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(87)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuo X, Speicher DW. A Method for Global Analysis of Complex Proteomes Using Sample Prefractionation by Solution Isoelectrofocusing Prior to Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis. Analytical Biochemistry. 2000;284:266–278. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ros A, Faupel M, Mees H, van Oostrum J, Ferrigno R, Reymond F, Michel P, Rossier JS, Girault HH. Protein Purification by Off-Gel Electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2002;2:151–156. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200202)2:2<151::aid-prot151>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramachandran P, Boontheung P, Xie YM, Sondej M, Wong DT, Loo JA. Identification of N-Linked Glycoproteins in Human Saliva by Glycoprotein Capture and Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Proteome Research. 2006;5:1493–1503. doi: 10.1021/pr050492k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han MJ, Herlyn M, Fisher AB, Speicher DW. Microscale Solution Ief Combined with 2-D Dige Substantially Enhances Analysis Depth of Complex Proteomes Such as Mammalian Cell and Tissue Extracts. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:695–705. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myung JK, Lubec G. Use of Solution-Ief-Fractionation Leads to Separation of 2673 Mouse Brain Proteins Including 255 Hydrophobic Structures. Journal of Proteome Research. 2008;5:1267–1275. doi: 10.1021/pr060015h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michel PE, Crettaz D, Morier P, Heller M, Gallot D, Tissot JD, Reymond F, Rossier JS. Proteome Analysis of Human Plasma and Amniotic Fluid by Off-Gel (Tm) Isoelectric Focusing Followed by Nano-Lc-Ms/Ms. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:1169–1181. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbert B, Righetti PG. A Turning Point in Proteome Analysis: Sample Prefractionation Via Multicompartment Electrolyzers with Isoelectric Membranes. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:3639–3648. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200011)21:17<3639::AID-ELPS3639>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin AJP, Hampson F. New Apparatus for Isoelectric-Focusing. Journal of Chromatography. 1978;159:101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogle D, Ho A, Gibson T, Rylatt D, Shave E, Lim P, Vigh G. Preparative-Scale Isoelectric Trapping Separations Using a Modified Gradiflow Unit. Journal of Chromatography A. 2002;979:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)01601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.EsteveRomero JS, Bossi A, Righetti PG. Purification of Thermamylase in Multicompartment Electrolyzers with Isoelectric Membranes: The Problem of Protein Solubility. Electrophoresis. 1996;17:1242–1247. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150170712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shave E, Vigh G. Preparative-Scale, Recirculating, Ph-Biased Binary Isoelectric Trapping Separations. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:381–387. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim P, North R, Vigh G. Rapid Isoelectric Trapping in a Micropreparative-Scale Multicompartment Electrolyzer. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:1851–1859. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waller LN, Shores K, Knapp DR. Shotgun Proteomic Analysis of Cerebrospinal Fluid Using Off-Gel Electrophoresis as the First-Dimension Separation. Journal of Proteome Research. 2008;7:4577–4584. doi: 10.1021/pr8001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manadas B, English JA, Wynne KJ, Cotter DR, Dunn MJ. Comparative Analysis of Offgel, Strong Cation Exchange with Ph Gradient, and Rp at High Ph for First-Dimensional Separation of Peptides from a Membrane-Enriched Protein Fraction. Proteomics. 2009;9:5194–5198. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubner NC, Ren S, Mann M. Peptide Separation with Immobilized Pi Strips Is an Attractive Alternative to in-Gel Protein Digestion for Proteome Analysis. Proteomics. 2008;8:4862–4872. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Godoy LMF, Olsen JV, Cox J, Nielsen ML, Hubner NC, Frohlich F, Walther TC, Mann M. Comprehensive Mass-Spectrometry-Based Proteome Quantification of Haploid Versus Diploid Yeast. Nature. 2008;455:1251–U1260. doi: 10.1038/nature07341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lengqvist J, Uhlen K, Lehtio J. Itraq Compatibility of Peptide Immobilized Ph Gradient Isoelectric Focusing. Proteomics. 2007;7:1746–1752. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chenau J, Michelland S, Sidibe J, Seve M. Peptides Offgel Electrophoresis: A Suitable Pre-Analytical Step for Complex Eukaryotic Samples Fractionation Compatible with Quantitative Itraq Labeling. Proteome Science. 2008:6. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim P. Dissertation. Texas A&M University; College Station: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lalwani S, Shave E, Vigh G. High-Buffering Capacity Hydrolytically Stable, Low-Pl Isoelectric Membranes for Isoelectric Trapping Separations. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:3323–3330. doi: 10.1002/elps.200406045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalwani S, Shave E, Fleisher HC, Nzeadibe K, Busby MB, Vigh G. Alkali-Stable High-Pl Isoelectric Membranes for Isoelectric Trapping Separations. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:2128–2138. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleisher HC, Vigh G. Hydrolytically Stable, Diaminocarboxylic Acid-Based Membranes Buffering in the Ph Range from 6 to 8.5 for Isoelectric Trapping Separations. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:2511–2519. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleisher-Craver HC, Vigh G. Pva-Based Tunable Buffering Membranes for Isoelectric Trapping Separations. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:4247–4256. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Expasy: The Proteomics Server for in-Depth Protein Knowledge and Analysis. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradford MM. Rapid and Sensitive Method for Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosas-Acosta G, Russell WK, Deyrieux A, Russell DH, Wilson VG. A Universal Strategy for Proteomic Studies of Sumo and Other Ubiquitin-Like Modifiers. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2005;4:56–72. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400149-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins DN, Pappin DJC, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-Based Protein Identification by Searching Sequence Databases Using Mass Spectrometry Data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knochenmuss R, Stortelder A, Breuker K, Zenobi R. Secondary Ion-Molecule Reactions in Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2000;35:1237–1245. doi: 10.1002/1096-9888(200011)35:11<1237::AID-JMS74>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cargile BJ, Stephenson JL. An Alternative to Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Isoelectric Point and Accurate Mass for the Identification of Peptides. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76:267–275. doi: 10.1021/ac0352070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR. Large-Scale Analysis of the Yeast Proteome by Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology. Nature Biotechnology. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breci L, Hattrup E, Keeler M, Letarte J, Johnson R, Haynes PA. Comprehensive Proteornics in Yeast Using Chromatographic Fractionation, Gas Phase Fractionation, Protein Gel Electrophoresis, and Isoelectric Focusing. Proteomics. 2005;5:2018–2028. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cargile BJ, Talley DL, Stephenson JL. Immobilized Ph Gradients as a First Dimension in Shotgun Proteomics and Analysis of the Accuracy of Pi Predictability of Peptides. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:936–945. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cargile BJ, Sevinsky JR, Essader AS, Stephenson JL, Bundy JL. Immobilized Ph Gradient Isoelectric Focusing as a First-Dimension Separation in Shotgun Proteomics. Journal of Biomolecular Techniques. 2005;16:181–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. AutoCAD drawing of the MSWIFT separation device. All major features of the MSWIFT are illustrated. Specific details outlining the construction and assembly of the MSWIFT device have been previously described [25, 32]

Table S2. Summary of the number of proteins and peptides assigned from the two-stage fractionation of yeast tryptic peptides. For comparison the results from performing only one-stage of fractionation is included in the first column. Using the two-stage separation scheme clearly increases the number of peptides and protein assignments.