Abstract

Cancer initiation and progression is strongly influenced by the tumor microenvironment consisting of various types of host cells (inflammatory cells, vascular cells and fibroblasts), extracellular matrix and non-matrix molecules. Host cells play a defining role in two major processes crucial for tumor growth: angiogenesis and escape from immune surveillance. The interdependence of these processes resemble the principles of Yin and Yang, as the stimulation of tumor angiogenesis inhibits effective immune responses, while angiogenesis inhibition may have the opposite effect. These considerations may be useful in developing anticancer strategies based on the potentially synergistic combinations of antiangiogenic and immunostimulatory drugs.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Immune surveillance, Microenvironment, Combined antitumor strategy

Introduction

Tumor progression bears certain analogy to Darwinian evolution as new cellular variants constantly emerge and are subjected to forces of positive and negative selection [1, 2]. The resulting successful cellular populations often possess the ability to recruit host cells via secreted cytokines, chemokines and growth factors. These factors act not only on the constituents of local tissues, but also on various types of cells from bone marrow and bloodstream [2, 3]. The recruited cells include hematopoietic inflammatory cells, such as monocytes, macrophages, granulocytes, mast cells, dendritic cells and myeloblastic suppressor cells [4]. Tumor cells can also recruit fibroblasts [5] and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) [6]. Many of these cells contribute to the formation of the molecular scaffold in the form of extracellular matrix (ECM), and together constitute the unique functional compartment termed tumor stroma [7] or, more broadly, tumor microenvironment [8].

Constituents of tumor stroma as modulators of angiogenesis and immune responses

In many instances, the cellular compartment of tumor stroma is dominated by inflammatory cells, especially macrophages which differ phenotypically from that of macrophages located in normal tissues [9, 10]. Macrophages found in solid tumors (tumor-associated macrophages or TAMs) may display an M2 phenotype and possess mainly immunosuppressive functions (↓IL-12, ↑IL-10 phenotype), whereas those present in normal tissues display an M1 phenotype and play predominantly immunostimulatory (↑IL-12, ↓IL-10 phenotype) and cytocidal roles.

TAMs form complex paracrine networks, together with neoplastic, endothelial and immune cells [4, 9]. Direct elimination of TAMs markedly suppresses growth of experimentally induced animal tumors [11].

TAMs secrete several factors with a broad spectrum of biological activity: proangiogenic factors targeting endothelial cells (e.g. VEGF, EGF, FGF, PDGF), growth factors affecting neoplastic cells directly [e.g. IL-6, CXCL8 (IL-8), EGF], immunosuppressive factors (e.g. VEGF, IL-10, TGF-β) and ECM proteins, such as fibrin and collagen. Using enzymes such as MMP7, MMP9, MMP12 and uPA, these macrophages are capable of modifying and reconstructing ECM [9, 10].

VEGF plays a double role: it can act as a proangiogenic as well as an immunosuppressive factor. VEGF as a proangiogenic factor inhibits maturation of immature dendritic cells (iDCs) [4]. This maturation process is also affected by TGF-β, lactate and osteopontin. Hypoxia also induces iDC cells to release VEGF and CXCL8 which, in turn, inhibit maturation of other iDC cells leading to an impaired T cell response.

Another major cellular component represented in tumor stroma are cancer (or tumor)-associated fibroblasts (CAFs or TAFs) [5]. Some data suggest that these stromal fibroblasts may be derived from blood-circulating precursors, such as mesenchymal stem cells [12]. Because they express α-smooth muscle actin, CAFs have also been likened to, or even termed myofibroblasts [5]. Fibroblasts, endothelial cells and neoplastic cells secrete an ECM metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN), which drives differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. This could be, at least in part, attributed to the effects of VEGF [13]. In this environment, endothelial cells may also undergo the so-called endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EndMT), a process marked by the expression of the fibroblast-specific protein-1 (FSP1) and downregulation of endothelial cell-specific adhesion protein CD31/PECAM [14].

CAFs synthesize ECM proteins, such as type-I collagen and tenascin [5]. They also secrete several soluble growth factors, including: EGF, PDGF, bFGF, HGF and IGF, as well as ECM-degrading enzymes, such as MMP2, MMP3 and MMP9 [13]. In addition, tumor-related fibroblasts also produce factors that modulate inflammatory responses, such as IL-1β and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), as well as factors that influence tumor angiogenesis. Of particular significance is the expression of VEGF [15] and stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1/CXCL12), a chemokine involved in recruitment of EPCs from the bone marrow [13]. Indeed, CAFs contribute to both proangiogenic and immunosuppressive circuitry, the latter involving production of TGF-β [13].

Tumor growth, angiogenesis and antitumour responses were shown to be significantly influenced by the myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) (in mice defined as: CD11b+/Gr1+) [7, 16]. Differentiation of bone marrow progenitor cells into CD11b+/Gr1+ cells and macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells coincides with secretion of G-CSF and GM-CSF by neoplastic cells and fibroblasts. Immature CD11b+/Gr1+ cells, the macrophages differentiated from CD11b+/Gr1+, as well as iDCs have proangiogenic and immunosuppressive properties. Angiogenesis is strongly induced by proangiogenic cytokines VEGF and BV8, secreted by neutrophils, as well as by stromal MMP9, which can release VEGF from ECM stores. CD11b+/Gr1+ cells have immunosuppressive properties, as they inhibit activities of T lymphocytes and NK cells. This is attributed to the effects of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and arginase 1. Direct contacts between MDSC cells and T lymphocytes cause the suppressor cells to inactivate the T cell receptor (TCR) via secreted NO and nitrosylation [17]. On the other hand, VEGF secreted by CD11b+/Gr1+ derived macrophages and neutrophils inhibit maturation of iDC [7].

Inflammatory cells recruited by neoplastic cells also include TIE-2-expressing monocytes (TEMs), granulocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils, iDCs and mast cells. All of these cells show proangiogenic properties. In particular, TEMs harboring the angiopoietin receptor TIE-2 [4] secrete proangiogenic factors, including bFGF. These cells also elaborate angiopoietin 2 (Ang-2) which prevents them from secreting IL-12, an antiangiogenic cytokine [18].

The hematopoietic cells recruited by neoplastic cells (i.e. macrophages, dendritic cells, iDCs, and CD11b+/Gr1+ cells) as well as mesenchymal cells (fibroblasts) display a proangiogenic and immunosuppressive phenotype [19]. Their involvement in the formation of novel blood vessels consists of supplying proangiogenic factors and ECM-modifying enzymes. It seems that some of these cells can undergo phenotypic transformation into endothelial cells [19].

Interplay between tumor vasculature and immune effector mechanisms

Newly formed tumor vasculature differs from normal one both structurally (vascular network architecture) and functionally [20]. Fluctuations of blood flow in such vessels result in intermittent hypoxia in adjacent neoplastic cells [21].

Hypoxia triggers reprogramming of various metabolic pathways in cancer cells and this promotes malignant progression [22–24]. Oxidative phosphorylation is inhibited in cancer cells which instead rely on aerobic glycolysis [25]. Tumor microenvironment, acidified by lactic acid, can stimulate invasive properties of cancer cells. Acidification results in immunosuppression by inhibiting the activity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Hypoxic cancer cells express a mutator phenotype which can contribute to the appearance of new genetic variants. This confers tumor cells a great survival advantage [26].

One of the factors inducing epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is underoxygenation [27, 28]. Owing to this transdifferentiation process, epithelial neoplastic cells acquire the ability to translocate. In addition, EMT-derived neoplastic cells show phenotypic characteristics of cancer stem cells, i.e. the ability of self-renewal, refraction to apoptosis and senescence signals [29]. The immunosuppressive phenotype of cells making up the tumor microenvironment results from the interplay of factors secreted by these cells (VEGF, TGF-β, IL-10 and PGE2) and acting primarily on T lymphocytes and dendritic cells [30–32]. This phenotype promotes immune escape of neoplastic cells. Cancer cells develop several strategies in this complex process. One strategy is to avoid recognition and elimination by T cells. Another involves inhibiting the activity or damaging certain immune response elements by neoplastic (or other) cells.

An example of immunosuppressive mechanism involving proangiogenic factors is the downregulation of adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and E-selectin-adhesion molecule expression; all of them are involved in the interactions between leukocytes and vascular endothelium [33]. These molecules help leukocytes to penetrate the vascular wall into the surrounding tissue. Mitogenic factors, such as VEGF and EGF, acting via epigenetic mechanisms, downregulate the expression of these adhesion molecules on vascular endothelium. The lack of leukocyte adhesion receptors and the unresponsiveness to inflammatory signals, termed together tumor endothelial cell anergy, result in the abrogation of immune surveillance and immune escape of the tumor. Inhibition of angiogenesis (angiostasis) may, however, reverse this process and reduce the immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Immune selection that accompanies advancing immunosuppression ultimately leads to the formation of neoplastic tumor, a “false” lymphoid organ in which certain cells composing it (iDCs, TAMs, MDSCs, regulatory T lymphocytes) and various immunosuppressive factors prevent an efficient immune response directed against cancer cells [34].

Immunosuppressive activity of cells forming the tumor microenvironment seems to be significant at the early stages of progression, when cancer cells are not capable of avoiding or destroying cellular elements of the immune response [34]. Immunosuppressive factors secreted by these stromal cells can be the cancer cells’ first line of defense against the attack of the immune system. New genetic variants of neoplastic cells that appear during tumor progression can acquire improved defense mechanisms (for example specific elimination of T lymphocytes) that are far more efficient than those evolved by tumor stromal cells.

The two major processes in which these stromal cells are involved, i.e. angiogenesis and immunosuppression, have a strong impact on tumor progression. Together, they form a specific microenvironment (hypoxia, acidification, altered ECM) which affects the selection of neoplastic cells with certain definite phenotype characteristics. Tumor stromal cells enhance proangiogenic and immunosuppressive signals from neoplastic cells. On the one hand, owing to their proangiogenic features, the stromal cells are involved in the formation of blood and lymphatic vessels required for the malignant progression of neoplastic cells. On the other hand, they weaken the functioning of the immune system and protect neoplastic cells from being eliminated.

Tumor microenvironment-forming cells are thus active players in tumor progression [8]. Phenotypic and epigenetic alterations that occur in the cells composing tumor stroma cause some of them to become tumor specific (vide: CAFs and TAMs). The activity of these cells has strong impact on initiation, progression and metastatic properties of neoplastic cells.

Tumor stromal cells have their share in developing specific resistance to apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutics, radiotherapy and the death receptors [35]. These cells secrete numerous cytokines, chemokines and growth factors. The ability of neoplastic cells to adhere to fibroblasts or ECM proteins such as fibronectin, laminin and collagen (cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance, CAM-DR) combined with tumor stromal cell-secreted cytokines, chemokines and growth factors can cause development of specific resistance of neoplastic cells. This tumor microenvironment-induced resistance of cancer cells is transitional in character and is lost when neoplastic cells are transferred into a different environment.

VEGF plays a prominent role in the rise of proangiogenic and immunosuppressive phenotype of both neoplastic and stromal cells. VEGF is a major proangiogenic growth factor secreted by neoplastic and stromal cells. At the same time, VEGF is an immunosuppressive agent inhibiting maturation of dendritic cells and thus impairing the functioning of the immune system. It cannot be excluded that other pleiotropic factors, such as TGF-β [36] and TNF-α [37], similarly play proangiogenic and immunosuppressive roles. Vaccination with agents that inhibit activity of TGF-β enhance vaccine efficacy [38, 39].

Elimination of vascular endothelial cells or inhibiting their proliferation does affect the sustained growth of neoplastic cells [40–42]. Inhibition of angiogenesis blocks cancer cells’ growth. This effect of starving cancer cells is at the basis of antiangiogenic or vascular-disruptive therapies. Combinations of antiangiogenic therapy with chemotherapy seem an obvious therapeutic approach [43, 44] and such strategies “sensitize” neoplastic cells to chemotherapeutics and their efficacy is demonstrated by at least partial elimination of chemotherapy-resistant cancer stem cells [45].

However, there are some limitations of the use of antiangiogenic drugs. The drawbacks include their relatively high toxicity [46] and unexpected cellular resistance [47]. This resistance may be caused by the presence of numerous proangiogenic signals which duplicate each other (besides VEGF, several other factors induce angiogenesis, e.g. PlGF, BV8, etc.) [48, 49]. Some data point at an increased drug resistance of tumor vascular endothelial cells, as compared to their normal counterparts [50].

Antiangiogenic drugs also exert paradoxical effects. Although they inhibit growth of primary tumors in experimental animals, they have no apparent effect on metastases [51, 52].

Therapeutic implications of the nexus between tumor angiogenesis and immunomodulation

The proangiogenic phenotype of neoplastic and stromal cells is simultaneously an immunosuppressive one. Therefore, the following two therapeutic scenarios can be proposed:

Polarization of the proangiogenic and immunosuppressive phenotype of tumor stromal cells towards an antiangiogenic phenotype capable of inducing immune response.

Induction of immune response by antiangiogenic drugs.

The first scenario is supported by the results of a study by Guiducci et al. [53]. CpG oligonucleotides and an antibody directed against the interleukin IL-10 receptors (IL-10R) induced a switch in M2 macrophages (proangiogenic and immunosuppressive) into M1 macrophages (antiangiogenic and immunostimulating) [19]. This phenotype polarization of M2 macrophages resulted in inhibition of growth of experimental tumors.

The studies of Li et al. [54] and Manning et al. [55] illustrate the second scenario: inhibiting the activity of VEGFR2 receptor by an anti-VEGFR2 monoclonal antibody activates T lymphocytes and impairs tumor growth; inhibiting the activity of VEGF by a soluble VEGF receptor increases the number of effector T lymphocytes as well as increases the ratio of effector versus regulatory (Treg) cells.

Antiangiogenic factors, such as bevacizumab and sunitinib stimulate various elements of the immune response and abrogate immunosuppression. Bevacizumab (Avastin) is an anti-VEGF antibody, whereas sunitinib (Sutent) is an inhibitor of protein-tyrosine kinases (including VEGFR1–VEGFR3 receptors), as well an inhibitor of c-kit and receptors for platelet-derived growth factors (α and β) [56].

The effect of bevacizumab and sunitinib on the maturation of dendritic cells and a decline in MDSCs and Treg lymphocyte numbers was confirmed in preclinical and clinical studies [57–63].

Inhibition via aminobiphosphonates of matrix MMP-9 metalloproteinase (an enzyme releasing VEGF from ECM and triggering angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis [64]), decreases the number of MDSC cells in both bone marrow and peripheral blood. By reducing the number of MDSC, the bisphosphonates (e.g. zoledronate or pamidronate) overcome the tumor-induced immune suppression and break the link between tumor growth and expression of MDSC cells [65].

Lastly, the work of Griffioen et al. [66] has shown that antiangiogenic factors (e.g. anginex, endostatin, angiostatin) or chemotherapeutics (e.g. paclitaxel) significantly stimulate leukocyte–vessel wall interactions by circumventing endothelial cells’ anergy with upregulated adhesion molecules on tumor endothelium. These authors have demonstrated, using two murine tumor models, a several fold enhancement of tumor infiltrating leukocytes, including tumor-directed cytotoxic lymphocytes after administration of antiangiogenic factors. The role of NK4, a competitive antagonist of HGF and an antiangiogenic agent was shown in the regression of CT26 colon tumor: immunohistochemistry of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes showed that the ratio of CD8/CD4 in this tumor was significantly higher than in control [67].

Preliminary reports of combined therapies involving angiostatics and chemotherapeutics showed leukocyte infiltration to be enhanced even more but which subtypes are homed into tumors is not known [66].

Clinical trials of interferon-α in combination with bevacizumab [68] or sorafenib [69, 70], involving patients with metastatic renal carcinoma concluded a significant improvement in progression-free survival, when compared with monotherapies.

Future cancer treatment strategies targeting both tumor stroma and cancer cells will very likely involve combinations of various therapeutic modalities. The rationale for this is the promise of potential therapeutic advantages (e.g. synergy), metaphorically alluded to by the motto of three musketeers (“one for all”) [71] and substantiated by recent preclinical and clinical data on the multimodal approach involving radiation, immunotherapy and antiangiogenic agents. A combination strategy involving antiangiogenic drugs inhibiting growth of tumor vasculature as well as abrogating immunosuppression and boosting immune response against the tumor represents a step in that direction.

Conclusions

To conclude, two types of therapeutic strategies featuring antiangiogenic drugs can be envisioned. The first is based on the premise that the destruction of tumor stromal cells with antiangiogenic drugs will trigger death of neoplastic cells (indirect elimination of drug-resistant neoplastic cells). This approach would involve combinations of antiangiogenic drugs (or vascular-disruptive drugs) with novel chemotherapeutics selectively eliminating cells resistant to classical chemotherapeutics. One cannot exclude the possibility that there are other explanations as to how such combinations work, e.g. vessel normalization, etc.

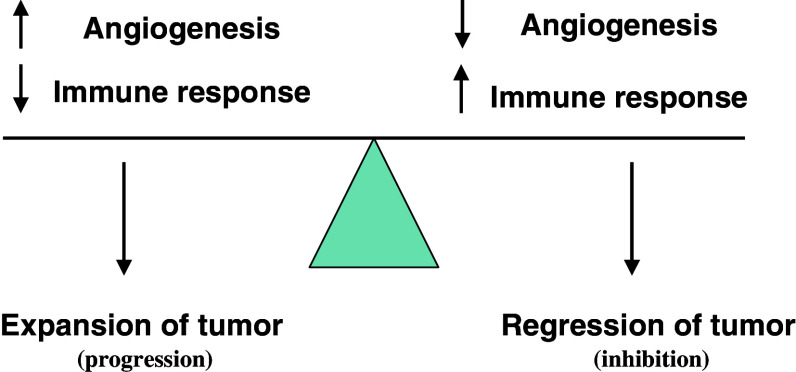

The second type of therapeutic strategy involving antiangiogenic drugs will focus on modifying the phenotype of neoplastic and stromal cells, from proangiogenic and immunosuppressive to antiangiogenic and immunostimulatory one. Major roles in this strategy will belong to combinations of antiangiogenic and immunostimulatory drugs. Potentially, neoplastic cells may also be eliminated indirectly by combinations of antiangiogenics and immunotherapy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between angiogenesis and immune response. Suppression of tumor growth results from inhibition of angiogenesis and stimulation of immune response (i.e. abrogation of immunosuppression that accompanies angiogenesis)

Obviously, the common intention of both scenarios is to gain better and more precise control of tumor cell growth.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend special thanks to Drs. Maria Wysocka and Janusz Rak for critical reading of this manuscript. We apologize to any investigators whose papers could not be cited owing to space limitations. This study was supported by a research grant (number NN401 018337) from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Poland).

Conflicts of interest statement

None.

Abbreviations

- CAF

Cancer-associated fibroblast

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- EPC

Endothelial progenitor cell

- EMT

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- IDC

Immature dendritic cell

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- NK

Natural killer

- TAM

Tumor-associated macrophage

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-beta

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merlo LM, Pepper JW, Reid BJ, Maley CC. Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:924–935. doi: 10.1038/nrc2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan DJ, Ciarrocchi A, Mellick AS, Jaggi JS, Bambino K, Gupta S, Heikamp E, McDevitt MR, Scheinberg DA, Benezra R, Mittal V. Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells are a major determinant of nascent tumor neovascularization. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1546–1558. doi: 10.1101/gad.436307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shojaei F, Zhong C, Wu X, Yu L, Ferrara N. Role of myeloid cells in tumor angiogenesis and growth. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu M, Polyak K. Microenvironmental regulation of cancer development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allavena P, Sica A, Solinas G, Porta C, Mantovani A. The inflammatory micro-environment in tumor progression: the role of tumor-associated macrophages. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stout RD, Watkins SK, Suttles J. Functional plasticity of macrophages: in situ reprogramming of tumor-associated macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo Y, Zhou H, Krueger J, Kaplan C, Lee S-H, Dolman C, Markowitz D, Wu W, Liu C, Reisfeld RA, Xiang R. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages as a novel strategy against breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2132–2141. doi: 10.1172/JCI27648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishra PJ, Mishra PJ, Glod JW, Banerjee D. Mesenchymal stem cells: flip side of the coin. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1255–1258. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes CC. Endothelial–stromal interactions in angiogenesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:204–209. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282f97dbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeisberg EM, Potenta S, Xie L, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Discovery of endothelial to mesenchymal transition as a source for carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10123–10128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hlatky L, Hahnfeldt P, Tsionou C, Coleman CN. Vascular endothelial growth factor: environmental controls and effects in angiogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:S151–S156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nature. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagaraj S, Gabrilovich D. Tumor escape mechanism governed by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2561–2563. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis CE, De Palma M, Naldini L. Tie2-expressing monocytes and tumor angiogenesis: regulation by hypoxia and angiopoietin-2. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8429–8432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noonan DM, De Lerma Barbaro A, Vannini N, Mortara L, Albini A. Inflammation, inflammatory cells and angiogenesis: decisions and indecisions. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:31–40. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald DM, Choyke PL. Imaging of angiogenesis: from microscope to clinic. Nat Med. 2003;9:713–725. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewhirst MW, Cao Y, Moeller B. Cycling hypoxia and free radicals regulate angiogenesis and radiotherapy response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:425–437. doi: 10.1038/nrc2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bristow RG, Hill RP. Hypoxia, DNA repair and genetic instability. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:180–192. doi: 10.1038/nrc2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denko NC. Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:705–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaupel P. Hypoxia and aggressive tumor phenotype: implications for therapy and prognosis. Oncologist. 2008;13(Suppl 3):21–26. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S3-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill RP, Marie-Egyptienne DT, Hedley DW. Cancer stem cells, hypoxia and metastasis. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao M-J, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Polyak K, Brisken C, Yang J, Weinberg RA. The epithelial–mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smyth MJ, Dunn GP, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting: the roles of immunity in suppressing tumor development and shaping tumor immunogenicity. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:1–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart TJ, Abrams SI. How tumours escape mass destruction. Oncogene. 2008;27:5894–5903. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bronte V, Mocellin S. Suppressive influences in the immune response to cancer. J Immunother. 2009;32:1–11. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181837276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffioen AW. Anti-angiogenesis: making the tumor vulnerable to the immune system. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1553–1558. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0524-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumor environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:263–274. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meads MB, Gatenby RA, Dalton WS. Environment-mediated drug resistance: a major contributor to minimal residual disease. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nrc2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bierie B, Moses HL. TGFβ: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:506–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balkwill F. Tumor necrosis factor and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nrc2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueda R, Fujita M, Zhu X, Sasaki K, Kastenhuber ER, Kohanbash G, McDonald HA, Harper J, Lonning S, Okada H. Systemic inhibition of transforming growth factor-β in glioma-bearing mice improves the therapeutic efficacy of glioma-associated antigen peptide vaccines. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6551–6559. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terabe M, Ambrosino E, Takaku S, O’Konek JJ, Venzon D, Lonning S, McPherson JM, Berzofsky JA. Synergistic enhancement of CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor vaccine efficacy by an anti-transforming growth factor-β monoclonal antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6560–6569. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;18:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature. 2005;438:967–974. doi: 10.1038/nature04483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kerbel RS. Antiangiogenic therapy: a universal chemosensitization strategy for cancer? Science. 2006;312:1171–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.1125950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Folkins C, Man S, Xu P, Shaked Y, Hicklin DJ, Kerbel RS. Anticancer therapies combining antiangiogenic and tumor cell cytotoxic effects reduce the tumor stem-like cell fraction in glioma xenograft tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3560–3564. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verheul HM, Pinedo HM. Possible molecular mechanisms involved in the toxicity of angiogenesis inhibition. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:475–485. doi: 10.1038/nrc2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bergers G, Hanahan D. Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shojaei F, Ferrara N. Refractorines to antivascular endothelial growth factor treatment: role of myeloid cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5501–5504. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebos JM, Lee CR, Kerbel RS. Tumor and host-mediated pathways of resistance and disease progression in response to antiangiogenic therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5020–5025. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiong Y-Q, Sun H-C, Zhang W, Zhu X-D, Zhuang P-Y, Zhang J-B, Wang L, Wu W, Qin L-X, Tang Z-Y. Human hepatocellular carcinoma tumor-derived endothelial cells manifest increased angiogenesis capability and drug resistance compared with normal endothelial cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4838–4846. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pàez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, Takeda T, Okuyama H, Viňals F, Inoue M, Bergers G, Hanahan D, Casanovas O. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ebos JM, Lee CR, Cruz-Munoz W, Bjamason GA, Christensen JG, Kerbel RS. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guiducci C, Vicari AP, Sangaletti S, Trinchieri G, Colombo MP. Redirecting in vivo elicited tumor infiltrating macrophages and dendritic cells towards tumor rejection. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3437–3446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li B, Lalani AS, Harding TC, Luan B, Koprivnikar K, Tu GH, Prell R, VanRoey MJ, Simmons AD, Jooss K. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade reduces intratumoral regulatory T cells and enhances the efficacy of a GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6808–6816. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manning EA, Ullman JG, Leatherman JM, Asquith JM, Hansen TR, Armstrong TD, Hicklin DJ, Jaffee EM, Emens LA. A vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 inhibitor enhances antitumor immunity through an immune-based mechanism. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3951–3959. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roskoski R., Jr Sunitinib: a VEGF and PDGF receptor protein kinase and angiogenesis inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;356:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kusmartsev S, Eruslanov E, Kübler H, Tseng T, Sakai Y, Su Z, Kaliberov S, Heiser A, Rosser C, Dahm P, Siemann D, Vieweg J. Oxidative stress regulates expression of VEGFR1 in myeloid cells: link to tumor-induced immune suppression in renal cell carcinoma. J Immunol. 2008;181:346–353. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Osada T, Chong G, Tansik R, Hong T, Spector N, Kumar R, Hurwitz HI, Dev I, Nixon AB, Lyerly HK, Clay T, Morse MA. The effect of anti-VEGF therapy on immature myeloid cell and dendritic cells in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1115–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0441-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wada J, Suzuki H, Fuchino R, Yamasaki A, Nagai S, Yanai K, Koga K, Nakamura M, Tanaka M, Morisaki T, Katano M. The contribution of vascular endothelial growth factor to the induction of regulatory T-cells in malignant effusions. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:881–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alfaro C, Suarez N, Gonzalez A, Solano S, Erro L, Dubrot J, Palazon A, Hervas-Stubbs S, Gurpide A, Lopez-Picazo JM, Grande-Pulido E, Melero I, Perez-Gracia JL. Influence of bevacizumab, sunitinib and sorafenib as single agents or in combination on the inhibitory effects of VEGF on human dendritic cell differentiation from monocytes. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1111–1119. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ko JS, Zea AH, Rini BI, Ireland JL, Elson P, Cohen P, Golshayan A, Rayman PA, Wood L, Garcia J, Dreicer R, Bukowski R, Finke JH. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2148–2157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hipp MM, Hilf N, Walter S, Werth D, Brauer KM, Radsak MP, Weinschenk T, Singh-Jasuja H, Brossart P. Sorafenib, but not sunitinib, affects function of dendritic cells and induction of primary immune responses. Blood. 2008;111:5610–5620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ozao-Choy J, Ma G, Kao J, Wang GX, Meseck M, Sung M, Schwartz M, Divino CM, Pan P-Y, Chen S-H. The novel role of tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the reversal of immune suppression and modulation of tumor microenvironment for immune-based cancer therapies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2514–2522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, Vu TH, Itoh T, Tamaki K, Tanzawa K, Thorpe P, Itohara S, Werb Z, Hanahan D. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Melani C, Sangaletti S, Barazzetta FM, Werb Z, Colombo MP. Amino-biphosphonate mediated MMP-9 inhibition breaks the tumor-bone marrow axis responsible for myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and macrophage infiltration in tumor stroma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11438–11446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dirkx AEMJ, oude Egbrink MGA, Castermans C, van der Schaft DWJ, Thijssen VLJL, Dings RPM, Kwee L, Mayo KH, Wagstaff J, Bouma-ter Steege JCA, Griffioen AW. Anti-angiogenesis therapy can overcome endothelial cell anergy and promote leukocyte-endothelium interactions and infiltration in tumors. FASEB J. 2006;20:621–630. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4493com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kubota T, Taiyoh H, Matsumara A, Murayama Y, Ichikawa D, Okamoto K, Fujiwara H, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M, Kikuchi S, Ochiai T, Sakakura C, Kokuba Y, Sonoyama T, Suzuki Y, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Otsuji E. Gene transfer of NK4, an angiogenesis inhibitor, induces CT26 tumor regression via tumor-specific T lymphocyte activation. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2879–2886. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, Ravaud A, Bracarda S, Szczylik C, Chevreau C, Filipek M, Melichar B, Bajetta E, Gorbunova V, Bay J-O, Bodrogi I, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Moore N. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet. 2007;370:2011–2103. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gollob JA, Rathmell WK, Richmond TM, Marino CB, Miller EK, Grigson G, Watkins C, Gu L, Peterson BL, Wright JJ. Phase II trial of sorafenib plus interferon alfa-2b as first- or second-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3288–3295. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryan CW, Goldman BH, Lara PN, Jr, Mack PC, Beer TM, Tangen CM, Lemmon D, Pan C-X, Drabkin HA, Crawford ED. Sorafenib with interferon alfa-2b as first-line treatment of advanced renal carcinoma: a phase II study of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3296–3301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kamrava M, Bernstein MB, Camphausen K, Hodge JW. Combining radiation, immunotherapy, and antiangiogenic agents in the management of cancer: the three musketeers or just another quixotic combination? Mol BioSyst. 2009;5:1262–1270. doi: 10.1039/b911313b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]