Abstract

The original signature of the transferrin (TF) family of proteins was the ability to bind ferric iron with high affinity in the cleft of each of two homologous lobes. However, in recent years, new family members that do not bind iron have been discovered. One new member is the inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase (ICA), which as its name indicates, binds to and strongly inhibits certain isoforms of carbonic anhydrase. Recently, mouse ICA has been expressed as a recombinant protein in a mammalian cell system. Here, we describe the 2.4 Å structure of mouse ICA from a pseudomerohedral twinned crystal. As predicted, the structure is bilobal, comprised of two α-β domains per lobe typical of the other family members. As with all but insect TFs, the structure includes the unusual reverse γ-turn in each lobe. The structure is consistent with the fact that introduction of two mutations in the N-lobe of murine ICA (mICA) (W124R and S188Y) allowed it to bind iron with high affinity. Unexpectedly, both lobes of the mICA were found in the closed conformation usually associated with presence of iron in the cleft, and making the structure most similar to diferric pig TF. Two new ICA family members (guinea pig and horse) were identified from genomic sequences and used in evolutionary comparisons. Additionally, a comparison of selection pressure (dN/dS) on functional residues reveals some interesting insights into the evolution of the TF family including that the N-lobe of lactoferrin may be in the process of eliminating its iron binding function.

Keywords: inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase, protein structure, transferrin family, pseudomerohedral twinned crystal, selection pressure (dN/dS)

Introduction

The transferrins (TFs) are 80 kDa bilobal glycoproteins that function in the transport of iron to cells and/or as antimicrobial agents in serum and other biological fluids.1,2 Founding members of the family include serum TF, ovotransferrin (OTF), which makes up ∼12% of the protein in egg white, and lactoferrin (LTF) found in milk, tears, and other bodily secretions. All available evidence suggests that members of the TF family arose from a gene duplication and fusion event giving rise to two homologous lobes, termed the N- and C-lobes.3,4 Each lobe is comprised of two subdomains (N1 and N2 as well as C1 and C2), which form a cleft in which a single ferric ion is reversibly bound within an extensive hydrogen bond network. Within each lobe of the founding members, ferric iron is coordinated to the side chains of two tyrosine residues, one histidine residue, one aspartate residue, and two oxygen atoms from a synergistic anion (carbonate) anchored by an arginine residue.5–8 Although the iron in each lobe of human transferrin (hTF), OTF, and LTF is bound to the same amino acid residues, substantial differences in the binding affinity exist among family members and between lobes.9–13 These differences are attributed, in large part, to substitutions in the amino acid residues that hydrogen bond to the primary ligands comprising the “second shell.”14 Due to the inherent flexibility of the binding cleft, TFs are promiscuous in their ability to bind other metals such as Ga3+, Al3+, Co3+, Cu2+, Pt2+, and In3+, to name just a few.15

As discussed in detail, extensive homology searches have identified additional members of the TF superfamily.16–18 One member is the inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase (ICA), which inhibits certain isoforms of carbonic anhydrase (CA), an enzyme that catalyzes the hydration of carbon dioxide to produce a bicarbonate and a proton.19,20 Various isoforms of CA are widespread and feature significant differences in activity, tissue localization, and function.21,22 Carbonic anhydrase isoform II (CAII) is the most abundant and the most ubiquitous of the isozymes; it is found in the red blood cells of all vertebrates (with the exception of agnathans and elasmobranchs).23 The available data indicates that the stoichiometry of the CA:ICA interaction is 1:1 and that ICA binds through its C-lobe to CAII with nanomolar affinity.18,24–26

The first identified ICA was isolated from pig serum after passage over a CA affinity column.26 Previously, CA inhibitory activity had been reported in the serum of mice, rats, rabbits, cats, dogs, sheep, and pigs.25,27,28 Notably, absent from this list is human serum. A search of the human genome identified a gene corresponding to ICA, which featured a premature stop codon following Trp128; because it is unlikely that this gene is functional, it has been classified as a pseudogene18 (We note that it is probably the same sequence originally identified by Schaeffer et al. as a TF pseudogene.29). In mammals that have retained functional ICA, it is found in the serum where it circulates at a concentration of ∼1 μM. Like other serum proteins including TF, ICA is made by and secreted from hepatocytes into the bloodstream. In spite of the substantial sequence similarity to hTF,24 neither porcine ICA (pICA) nor murine ICA (mICA) bind iron in either lobe.18,25 Interestingly, phylogenetic analysis suggests that ICA is the most recent member of the TF superfamily, appearing ∼90 million years ago.16,17 This suggests that on the evolutionary scale, the human ICA gene appeared and was then inactivated in a relatively short period of time.

It is clear that the TF scaffold has been used to carry out other functions besides the transport of iron and/or sequestration of this toxic, yet essential metal. In addition to ICA, a protein designated melanotransferrin (MTF) was discovered some 20 years ago.30 Although it was reported that MTF had lost the ability to bind iron in the C-lobe,31 its precise function remained unknown for many years. Recently, it has been clearly shown that MTF does not play a role in iron metabolism (in spite of retaining the ability to bind iron in the N-lobe), and that it appears to stimulate a specific subset of genes involved in proliferation and tumorigenesis in mice.32–34

In this study, we report the crystal structure of mICA allowing a detailed analysis of both the similarities and differences with other family members. Because both lobes of mICA were found to have closed clefts, the structure is most similar to pig TF with iron in each lobe (Fe2 pTF) [root mean squared deviation (RMSD) 1.7 Å, 59% sequence identity] and differs significantly from human TF lacking iron (apo) in which both the lobes are open (RMSD 8.8 Å, 61% identity).8,35 In addition, we examined the genomic databases for new members of the ICA family. Two new pseudogenes (chimp and macaque) were identified as well as two new ICA sequences (horse and guinea pig). These new sequences were used to examine the selection pressure placed upon codons for “functional” amino acids within the TF family in an effort to gain further insights into the ICA structure and possibly its function. It appears that ICAs are rapidly evolving.

Results and Discussion

Diffraction data and the twinning problem

Remarkably, mICA was found to crystallize across a wide range of PEG solutions [1500–10,000 molecular weights (MWs)]. In all cases, the crystal morphology was consistent, although the thickness of the crystals varied (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Diffraction data was processed to 2.4 Å with a completeness of 94.4% for the space group P21 (Table I) and an estimated twin fraction of between 0.42 (CCP4) and 0.48 (Phenix). Although this form of pseudomerohedral twinning is common with a β angle near 90°, it was initially masked by a noncrystallographic translation.36 The output parameters from the molecular replacement solution with Phaser were reasonable with Z-scores for each subdomain in the translation function from 8.0 to 17.9 and a final log likelihood gain (LLG) of 3904. The initial refinement of the structure was performed with Crystallography and NMR System (CNS) using the twinned data, and assumed perfect twinning (Rfree of 31.5%). Three refinement protocols were explored in parallel for the final phases of refinement. Using Phenix, the Rfree was below 29%, however, there was a larger difference between Rwork and Rfree compared with CNS, depending on the input parameters, as well as a decrease in the percentage of bonds in preferred and allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot. Using Refmac5.5, the structure could be refined to a Rfree of 32% using default parameters or 23.3% by applying Phase/FOM after density modification. This latter approach results in a higher degree of model bias, as well as very high B-factors after accounting for translation/liberation/screw motion (TLS) (125 Å2). Therefore, final refinement was taken from CNS, resulting in a Rfree of 30.1% against twinned data (28.5% detwinned) and reasonable B-factors (Table I). Because addition of water molecules only improved the Rfree by <0.2%, waters were not included in the final structure. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited [protein data bank (PDB) code 3MC2].

Table I.

Diffraction Data and Refinement Statistics for mICA

| Space group | P21 |

| Unit cell | a = 68.559 Å |

| b = 136.928 Å | |

| c = 155.575 Å | |

| β = 90.109° | |

| Resolution | 19.0–2.4 Å |

| Completeness (%) | 94.4 (71.8)a |

| Rmerge (%) | 7.3 (29.8) |

| I/σ | 18.3 (3.2) |

| χ2 | 1.15 (1.09) |

| Mosaicity | 0.73 |

| Reflections (unique) | 476,063 (105,646) |

| Redundancy | 4.45 (2.7) |

| Native patterson peak (fractional coord.) | 210.3 (0, 0, 0), 115.8 (0, 0, 0.5) |

| Matthews, N/asu, % solvent | 2.39, 4, 48.5 |

| Rwork (detwinned) | 23.9%b (23.3%) |

| Rfree (detwinned) | 30.1%b (28.5%) |

| Chains | A, B, C, D (674 AA ea.) |

| Residues (atoms) | 2696 (20,772) |

| Average B (main) | 66.2, 80.2, 70.8, 84.4 |

| Disulfides | 16 per chain |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favored and allowed | 97.7% |

| Generously allowed | 1.9% |

| Disallowed | 0.4% |

| Bond R.M.S. | 0.0099 |

| Angle R.M.S. | 1.4080 |

| Twin (fraction estimated) | h, −k, −l (0.42–0.48)c |

Number in parentheses denotes highest resolution bin.

Refinement against twinned data.

Perfect twinning (0.5) used in refinement due to high fraction.

Structure of mICA

The molecular replacement search was conducted using an ensemble of 10 structures for each of the four subdomains to improve the initial solution and to decrease potential model bias for a particular form. Combining the solutions generated four molecules in the asymmetric unit (A, B, C, and D) with B and D related to A and C, respectively, by noncrystallographic translational symmetry (NCS). Each bilobal molecule of mICA is comprised of two homologous domains (N-lobe and C-lobe) of ∼330 amino acids separated by a bridge (residues 329–332) for which no density was observed in any of the four molecules, as has been the case for several TF structures [Fig. 1(A)]. The two subdomains of each lobe (N1/N2 and C1/C2) are connected by two anti-parallel β-strands forming the “hinge,” which allows the domains to close or to open when iron is bound or released. Each subdomain is composed of a mixed β-sheet surrounded by α-helices (α-β domain), and together each lobe is quite similar to the “binding protein fold” observed in bacterial periplasmic proteins.38 The mICA fold is almost identical to that of the other TF family members.

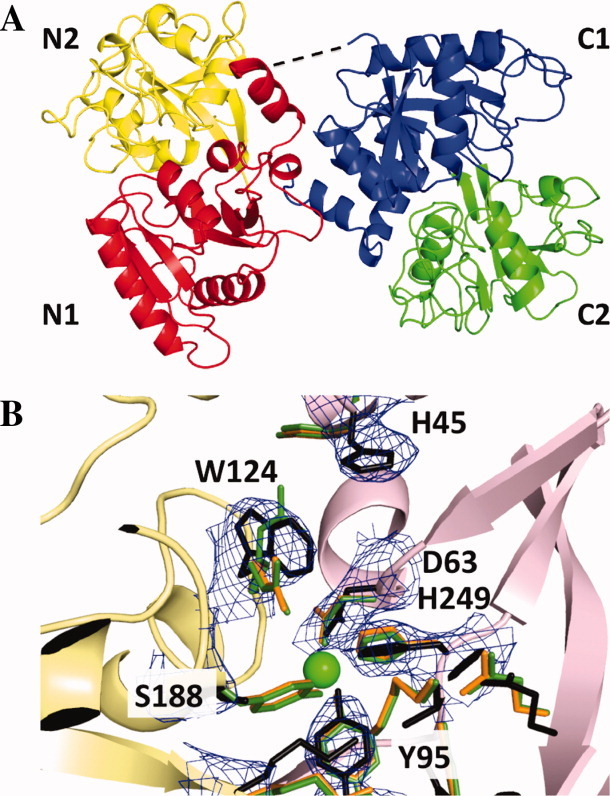

Figure 1.

(A) Ribbon diagram of the crystal structure of mICA. Subdomains N1 (red), N2 (yellow), C1 (blue), and C2 (green) are highlighted. The linker between lobes for which density was not observed is indicated by the dashed line. (B) The N-lobe cleft of mICA. Shown is the N1 subdomain (pink), N2 subdomain (yellow), mICA residues (black), residues for porcine TF (PDB: 1H76, orange),8 and residues for human TF (PDB: 1A8E)7 including the Fe atom (green) after least squares superposition. Electron density shown is 2Fo − Fc. All structural images produced using PyMOL.37 [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The non-NCS related chains have a RMSD of 1.3 Å. Each chain has a unique list of solvent exposed side chains lacking observed density. The regions that deviate the most between molecules are three solvent exposed loops in the N-lobe: residues 26–34, 134–141, and 213–219 and two loops in the C-lobe: residues 406–418 and 612–622. In addition to the similarity in the overall fold, mICA retains the characteristic strained Leu-Leu-Phe classical γ-turn in the N1 and C1 subdomains of each lobe, with the second position (Leu294 in the N-lobe and Leu632 in the C-lobe) in the disallowed region of the Ramachandran plot; only insect TFs lack this distinctive feature.17 We have previously suggested that the presence of the γ-turn (which immediately precedes Lys296 which is one half of the dilysine trigger in the N-lobe and Arg632 which is part of the triad in the C-lobe) provides structural rigidity to aid in the mechanism of iron release.2 This role is reminiscent of serine proteases, which features a γ-turn to correctly position the aspartic acid as part of their active site.39

Structural comparisons

Because both the lobes are closed, the mICA structure most closely resembles diferric porcine TF (1H76)8 with a RMSD of 1.7 Å for the full-length protein and 1.5 Å and 1.0 Å for the N- and C-lobes, respectively [Fig. 2(A)]. We note that no structure of diferric hTF currently exists. In comparison with human apo TF with both the lobes open (2HAU),35 the RMSD is 8.8 Å for full-length mICA and 6.3 Å for each lobe (Supporting Information Table S2A and S2B). Structural alignments of the subdomains comprising each lobe range from 0.8 to 1.4 Å for pig diferric transferrin (Fe2TF) and from 1.2 to 1.6 Å for human apo TF (Supporting Information Table S2C) indicating that the conformation and orientation of the lobes with respect to each other both have an influence.

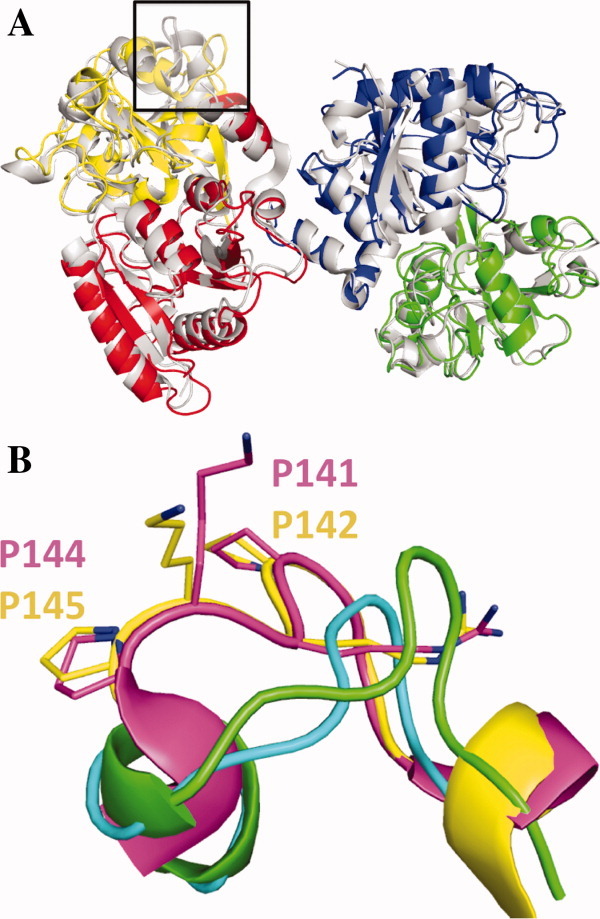

Figure 2.

(A) Least squares superposition of the structure of mICA with subdomain N1 (red), N2 (yellow), C1 (blue), and C2 (green) and the iron-bound form of porcine TF (PDB: 1H76)8 in white. (B) Detailed examination of the region indicated by the box in (A), which is implicated in binding to the TF receptor. Porcine TF in pink, human TF (PDB: 1A8E, yellow),7 mICA chain A in green, and mICA chain C in cyan. The largest positional shift relative to hTF were for the N-terminal residues of the sequence with 8.8 Å and 4.7 Å changes for mICA chain A and C, respectively. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

A region of mICA with significant deviation between human TF is a loop comprised of residues Pro142-Arg143-Lys144-Pro145 that corresponds to residues Gly139-Ser140-Arg141-Glu142 in the mICA structure. In human TF, three of four residues in this loop participate in binding of the N-lobe to the specific TF receptor.40 The corresponding residues in mICA are found in two different conformations for each of the non-NCS related molecules. Both of conformations deviate from TF [Fig. 2(B)], most likely due to a five amino acid deletion in ICA, which causes the helix leading into the loop to end prematurely.

Iron and anion binding

The metal binding sites of all TF family members that bind iron are located in clefts formed between the two subdomains comprising each lobe. Cleft opening for TF involves a twist followed by a substantial rotation ranging from 35° to 63°.2,41,42 As mentioned above, binding of iron and of the synergistic anion (carbonate) effectively locks the cleft in the closed conformation. Superposition of the iron-binding sites for the N- and C-lobes of human serum TF on the equivalent sites in mICA shows the positions of the iron binding residues and highlights the mutations in mICA that prevent binding of iron in each lobe (Fig. 3). The two substitutions in the N-lobe that prohibit iron binding in mICA are Trp124 (in place of Arg124 in hTF) and Ser188 (instead of Tyr188 in hTF). Significantly, introduction of Arg at position 124 and Tyr at position 188 in the N-lobe of mICA (W124R and S188Y mutants) allowed the N-lobe of the mutated mICA to bind ferric iron with high affinity.24 Interestingly, in the N-lobe of mICA, Trp124 occupies the same space occupied by Arg124 in the two conformations of the iron-bound structure of the N-lobe of human TF (PDB: 1A8E).7 Furthermore, in the closed, iron-bound N-lobe of hTF, Tyr45 is flipped out of the cleft, whereas in the open apo conformation it is rotated into the cleft by ∼160° as is observed for His45 for mICA. We also note that the two remaining ligands in mICA that are associated with iron binding in other family members (Asp63 and His249) are close enough to form a salt bridge [Fig. 1(B)].

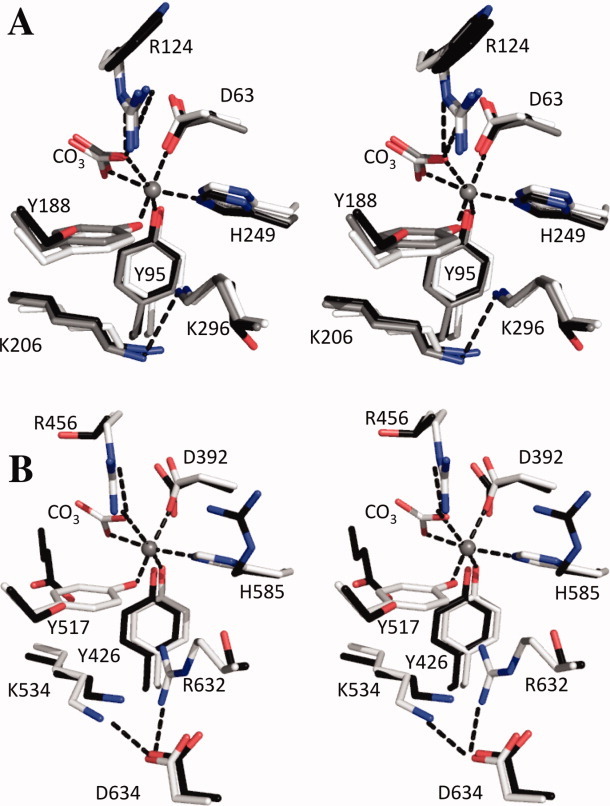

Figure 3.

Stereo images of the superposition of the iron binding sites for (A) N-lobes and (B) C-lobes of porcine TF (PDB: 1H76)8 (white) including the iron shown as a sphere, human TF (PDB: 1A8E)7 (grey), and mICA (black). Numbering in both panels is for human TF. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

In the iron binding cleft of the C-lobe of mICA, there are three substitutions that preclude iron binding: Ser520 (in place of Tyr517 in hTF), Arg588 (instead of His585 in hTF), and Thr457 (instead of Arg456 in hTF).17 As there are no obvious steric clashes that would interfere with iron binding, mutating the Ser, Arg, and Thr residues to Tyr, His, and Arg residues might result in a mICA C-lobe that could bind iron.

Significance of the closed lobes in the absence of iron?

The most surprising finding from the mICA structure is the observation that both the lobes are in the closed conformation normally associated with the iron-bound form of TF. Because we had shown that mICA does not bind iron in either lobe,18 this was unexpected and initially confounded molecular replacement efforts using intact lobes of the apo-conformation of human TF as the search model. Although a structure of apo LTF (1CB6) exists with a C-lobe that is nearly completely closed, the finding was attributed to crystal packing forces.43 Of possible relevance however, a theoretical modeling study based on LTF indicated that there is very little difference in energy between the open and closed conformations.44 Other work has suggested that TF family members exist in a dynamic equilibrium in which opened and closed conformations are constantly being sampled,2,45–48 similar to members of the periplasmic binding protein family.49,50 It is thought that the binding of the synergistic anion prepares the site for iron binding and the acquisition of iron strongly drives the equilibrium toward the closed form.51 However, no contiguous density that might be associated with anions such as acetate, ammonium, or carbonate was found in the vicinity of the remaining iron binding ligands in either lobe.

It is not clear whether the two lobes of mICA are sampling the open and closed conformations or if there are specific forces, which favor the closed conformation. Because crystal environments have been shown to have a clear influence on hinge-like motions in proteins, it is possible that crystal packing forces may account for the closed clefts.52 Nevertheless, we evaluated whether the differences in the amino acids within mICA might contribute to a change in the electrostatic potential of the cleft to promote closure. The electrostatic potential maps generated with PyMOL indicate that electrostatic interactions could maintain the C-lobe in a closed conformation as the surface within the cleft of the C-lobe shows that the C1 subdomain is predominantly electronegative, whereas the C2 subdomain is electropositive (Supporting Information Fig. S2). In contrast, the electrostatic analysis of the mICA N-lobe is less convincing. In the absence of clear electrostatic interaction between the subdomains, it is possible that the interaction between residues noted above (Asp63 from N1 and His249 from N2) could stabilize a closed cleft.

Sequence identification and phylogenetic analysis

In addition to the six mammalian ICA sequences that were reported previously,18 we have identified two more putative ICA sequences from genomic data for the guinea pig and the horse. Except for a missing 10 amino acid segment (448–457) in the horse ICA, these sequences appear to be complete. Confidence of their identification as ICA proteins came from creation of a multiple sequence alignment with representatives of other mammalian family members (Supporting Information Fig. S3). These additional sequences provided sufficient data to allow us to analyze the evolutionary constraints of specific residues. Of interest, searches of the chimp and macaque genomes confirmed the presence of pseudogenes in both of these species. This indicates that, like humans, other primates have gained and then lost a “functional” ICA.

Selection pressure on important residues in TF family members

Strong negative (purifying) selection occurs when the synonymous substitution rate (silent, dS) for a given codon or for a series of codons is greater than the nonsynonymous substitution rate (amino acid altering, dN). We quantified this pressure as the ratio of substitutions (dN/dS) for each TF family, where 1 indicates neutrality. Specifically, we examined important functional residues in various TF family members, including those involved in iron and anion binding as well as residues participating in the mechanism of iron release and in the hinge responsible for cleft opening and closing. The validity of this type of analysis is illustrated by serum TF in which all of these residues are under strong, consistent selection, or purifying pressure (low dN/dS ratios) (Tables II and III).

Table II.

Selection Pressure (dN/dS Ratios) of Significant N-Lobe Structural Elements within the TF Family

| N-lobe |

Fe-binding |

Anion |

Trigger |

Hinge |

Average dN/dS |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | Asp | Tyr | Tyr | His | Thr | Arg | Lys | Lys | Thr | Val | Pro | |

| Human TF | 63 | 95 | 188 | 249 | 120 | 124 | 206 | 296 | 93 | 246 | 247 | |

| Mouse ICA | 63 | 95 | Ser 188 | 249 | 120 | Trp 124 | 206 | Thr 296 | 93 | 250 | 251 | Whole molecule |

| TF (n = 18) | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.47 |

| LTF (n = 14) | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.09 | 0.82 | 0.23 | 0.56 (R) | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.55 |

| MTF (n = 11) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| ICA (n = 7) | 0.84 | 1.40 | 1.1 (S) | 0.08 | 1.50 | 1.2 (W) | 1.00 | 0.16 (T) | 0.08 | 1.40 | 0.16 | 0.68 |

Table III.

Selection Pressure (dN/dS Ratios) of Significant C-Lobe Structural Elements within the TF Family

| C-lobe |

Fe-binding |

Anion |

Triad |

Hinge |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | Asp | Tyr | Tyr | His | Thr | Arg | Lys | Arg | Asp | Ala | Gly | Arg | Ala | Pro |

| Human TF | 392 | 426 | 517 | 585 | 452 | 456 | 534 | 632 | 634 | 424 | 425 | 581 | 582 | 583 |

| Mouse ICA | 386 | 427 | Ser 520 | Arg 588 | 453 | Thr 457 | 537 | Ser 653 | 636 | Glu 425 | 426 | 584 | Val 585 | 586 |

| TF (n = 18) | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 1.10 | 0.31 | 1.50 | 0.47 | 0.09 |

| LTF (n = 14) | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.07 (N) | 0.05 (N) | 0.82 (E) | 0.12 | 0.89 (M) | 0.2 | 0.13 |

| MTF (n = 11) | 0.68 (S) | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.44 (A) | 0.02 (S) | 0.14 (R) | 0.03 (K) | 0.02 (A) | 0.21 (N) | 0.02 (S) | 0.02 (Q) | 0.31 (I) | 0.06 |

| ICA (n = 7) | 0.06 | 1.20 | 1.50 (S) | 1.1 (R) | 1.50 | 0.11 (T) | 0.05 | 0.08 (S) | 0.68 | 1.40 (E) | 0.11 | 1.50 | 0.07 (V) | 0.26 |

The six ligand and anion binding residues in the N-lobe are all well maintained in TF (Table II). Surprisingly, two of the four N-lobe iron-binding ligands (both Tyr residues) in LTF appear to be under only moderate purifying pressure (dN/dS ratios of 0.48 and 0.55), suggesting that iron binding in this lobe, although it can and does occur, may not be as important to its in vivo function (see below). For MTF, the iron and anion binding ligands in the N-lobe all show strong selection and conservation. This observation appears to be consistent with the fact that MTF definitely binds iron in the N-lobe.31 In contrast, in the ICA family, only one of the residues is strongly selected, His249 with a dN/dS ratio of 0.08 (Table II). Significant differences in the ratios of the other five residues in ICA show a clear loss of selective pressure consistent with losing the need to maintain the iron binding function.

In the C-lobe, all six ligand and anion binding residues are well maintained in both TF and LTF as indicated by dN/dS ratios below 0.13 (Table III). In MTF, two of the four iron binding ligands (Asp and Tyr) have higher ratios and, in fact, in human MTF the Asp is a Ser. Additionally, both the anion stabilizing residues in MTF have been replaced; interestingly, the serine replacing Arg456 is under strong purifying selection pressure (dN/dS = 0.02). The substitutions are consistent with the inability of the C-lobe of MTF to bind iron.31 The ICA family retains only a single iron binding residue, Asp386, which is strongly selected for; additionally, the anion stabilizing residue Arg456, which has been replaced by Thr457, is under strong selection. The remaining liganding and anion binding residues in mICA have dN/dS ratios above 1 indicating diversifying selection.

Amino acid residues involved in iron release

In the N-lobe of serum TF and OTF the dilysine trigger (Lys206-Lys296) is required for efficient iron release.53,54 LTF lacks this mechanism consistent with substitution of an Arg residue in some species and a lack of strong selection (dN/dS = 0.56). Of interest, MTF seems to have both lysines under strong purifying selection, although there is no direct experimental support for a dilysine trigger mechanism. In ICA, the Lys at position 206 displays neutral selection and a threonine residue replaces Lys296. Of significance, the Thr296 appears to be under strong purifying selection pressure (dN/dS = 0.16) perhaps indicating that it serves an important role. Supporting this suggestion is the unexplained failure, after multiple attempts, to produce a mutant of mICA in which Thr296 was replaced with Lys296.24

In the C-lobe of human TF, iron release is controlled by a triad of charged residues (Lys534, Arg632, and Asp634).55 In LTF, the Lys at the position equivalent to 534 is conserved but the other two positions are substituted by Asn residues, which are under strong selective pressure. The presence of these asparagine residues appears to account for the extremely tight binding and poor release of iron from this lobe.55 In MTF, all three residues of the triad are substituted by other amino acids which are under strong selective pressure, whereas in mICA, both the lysine (Lys536) and aspartic acid (Asp636) remain, but Ser634 replaces Arg632 (strongly indicating that the triad is not functional in mICA). Interestingly, both Lys537 and Ser634 are under strong purifying pressure (dN/dS < 0.08), whereas Asp636 is under moderate pressure (dN/dS = 0.68).

Residues comprising the hinge between the subdomains of each lobe

The subdomain movement that occurs during iron binding and release is controlled by hinge residues located on antiparallel strands linking the subdomains in all TFs. The specific residues involved in the hinge (Thr93, Val250, and Pro251 in the N-lobe and Glu425, Gly426, Arg584, Val585, and Pro586 in the C-lobe) in mICA were found to be somewhat conserved (5 of 8), although there is a considerable variation in the selection pressure (dN/dS between 0.08 and 1.5) (Tables II and III).

Selection pressure upon other regions of functional importance in TF family members

ICA is relatively a new family member, which may have functions in addition to inhibiting various isoforms of CA. Therefore, we looked at other regions of interest in certain family members. In particular, lactoferricin (residues 19–38) is a highly basic, disulfide-looped peptide released from LTF during gastric digestion and associated with strong antimicrobial properties.56 An NMR structure of the peptide revealed distorted antiparallel β-strands with the majority of hydrophobic residues on one face and basic residues on the other face.57 The mICA sequence and structure in this region are almost identical to other members of the TF family and, like them, lack the basic and hydrophobic residues that give rise to lactoferricin and are necessary for interactions with bacterial membranes.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-Ham F-12 nutrient mixture (DMEM-F12), antibiotic-antimycotic solution (100×), and trypsin were from the Gibco-BRL Life Technologies Division of Invitrogen. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals. Ultroser G (UG) is a serum replacement from Pall BioSepra (Cergy, France). Methotrexate from Bedford Laboratories was purchased at a local hospital pharmacy. All tissue culture dishes, flasks, and Corning expanded surface roller bottles were from local distributors. Ultracel 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane (MWCO) microcentrifuge devices were made by Amicon.

Purification of mICA

The cDNA sequence encoding the N-terminal hexa-histidine tagged mICA was inserted into the pNUT vector as previously described.18 For crystallization trials, the putative glycosylation sites, Asn470 and Asn645, were each mutated to aspartic acid to eliminate glycosylation. Therefore, the recombinant mICA was nonglycosylated significantly reducing the heterogeneity introduced by different carbohydrate species added by the BHK cells.24 As previously described, the mICA was produced and purified using methods that have been optimized for His-tagged hTF.18,24,58 The concentration of mICA was estimated using the calculated absorption coefficient of 86.5 mM−1 cm−1.59 We have experimentally determined that this calculation provides a remarkably accurate estimate of the concentration.60

Crystallization of mICA

The mICA was concentrated to 25 mg/mL in 100 mM NH4HCO3 (pH ∼ 8.0). Crystals initially appeared in PEG 3350 concentrations between 10% and 20%. The final optimized hanging drop condition used 100 mM ammonium acetate pH 7.4 and 12% PEG in the well, and 2 μL of protein solution and 1 μL of reservoir solution in the drop with the tray stored at 20°C. It generally took 3–7 days for the crystals to reach a size of 700 μm × 400 μm × 80 μm. Cryoprotection of the crystals involved titration of PEG 3350 in 5% increments to a final concentration of 35%; each addition was followed by a 30 min incubation at 20°C.

Data collection and structure determination

Data were collected on a Mar345 image plate detector using a Rigaku RU300 rotating anode generator at a temperature of 104 K. A low-resolution pass (5 min exposure) and a high-resolution pass (15 min exposure) were indexed and scaled together using the HKL Suite.62 Initial processing suggested a primitive orthorhombic lattice with a noncrystallographic translation along the c-cell axis, as determined by the native Patterson peak (0, 0, 0.5) at a peak height of 55% relative to the origin. However, unusual systematic absences, initial failures of molecular replacement, and a β angle fortuitously close to 90° (90.109°) suggested the possibility of twinning. Data was reprocessed as primitive monoclinic and submitted to the Padilla–Yeates twinning server.62 The results indicated partial merohedral twinning. The twin law (h, −k, −l) was submitted to the program Detwin using CCP4 version 6.163 to estimate the twinned fraction. A test set for 10% of the reflections was produced using CNS version 1.264 to be certain that the twin related reflections were in the same set.

Anticipating multiple subdomain movements, 10 structures of TF family members were threaded with the sequence for mICA using Chainsaw65 and broken into subdomains (N1, N2, C1, and C2) for molecular replacement using Phaser.66 Initial solutions for the C1 and C2 subdomains for one of the four chains in the asymmetric unit were obtained and used to eliminate the twin solutions for subsequent cycles of Phaser until all four chains were assembled from the subdomains. The iterative rounds of Phaser were performed such that after a proper subdomain solution was found, the NCS translation was applied to generate the duplicate molecule before the automated search for the next subdomain. Refinement protocols were explored in parallel for the structure against the twinned data using Phenix,67 CNS assuming perfect twinning as suggested for the high-twin fraction,36,68 and Refmac5.5 applying tight (main chain) and medium (side chain) NCS restraints with each subdomain as a TLS group.69 The final refinement was performed using CNS with model building performed using Coot.70

Genomic sequence identification

All protein and DNA sequences, including mICA, were retrieved from Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) searches of the Entrez, ENSEMBL, and Pre! ENSEMBL public genome databases71 using pICA as the query sequence. In certain cases, an assembled protein was unavailable, so transcript and putative protein sequences were derived from genomic sequences using FGENESH+ from Softberry (http://www.softberry.ru/berry.phtml). Initial alignments were made using CLUSTALW72 and were then imported into GeneDoc73 for refinement and additional analysis. SignalP74 was used to identify signal peptides, which were removed from the sequences. All sequences used are listed in Supporting Information Table S1.

Detection of selective forces

A minimum of eight nucleotide sequences from each TF family were codon-aligned using PAL2NAL.75 To examine whether individual amino acids/codons are undergoing natural selection (positive or negative), nonsynonymous versus synonymous substitutions and dN/dS ratios for individual codons were calculated using Selecton version 2.4 (http://selecton.tau.ac.il).76 As only four nucleotide sequences are available for avian OTF nucleotide sequences and a minimum of 10 or more homologues are preferred for this type of analysis, we chose not to include OTF in our comparisons.

Phylogenetic analyses

The best-fit evolutionary models were determined using PROTTEST.77 Neighbor-joining trees were created with MEGAv478 using the JTT+G model (gamma = 1.4) for amino acids,79 complete deletion of gaps, and 1000 bootstrap replications. Additional trees using the Poisson model were also created to confirm topology (data not included).

Conclusion

The TF gene duplication leading to the formation of the ICA family is a relatively recent evolutionary event. The 2.4 Å structure of mICA revealed that mICA has the same fold as other TF family members consistent with the original sequence analysis. Interestingly, mICA was found in the closed (usually iron bound) conformation, although no anions were observed in either cleft that might induce closure. Thus, closure could result from: (a) low-energy barrier between open and closed forms, (b) electrostatics (C-lobe), or (c) crystal packing forces. Comparison with other TF family members demonstrates that there has been little evolutionary pressure to maintain the canonical TF family features (iron and anion ligands, dilysine trigger or triad for iron release, or hinges) in ICAs. Selective force analysis supports the biochemical data that neither lobe of ICA nor the C-lobe of MTF can bind iron and suggests that the N-lobe of LTF may be eliminating its iron binding function. Why a functional ICA is absent in primates still remains a mystery, though it has been suggested to be related innate immunity.24

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Michael Sawaya for assistance in evaluating our twinned data.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BHK

baby hamster kidney cells

- CA

carbonic anhydrase

- CAII

carbonic anhydrase isoform II

- CNS

crystallography and NMR system

- DMEM-F12

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-Ham F-12

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- Fe2TF

diferric transferrin

- hTF

human transferrin

- ICA

inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase

- LLG

log likelihood gain

- LTF

lactoferrin

- mICA

murine inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase

- MTF

melanotransferrin

- MW

molecular weight

- NCS

noncrystallographic symmetry

- OTF

ovotransferrin

- PDB

protein data bank

- pICA

porcine inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase

- RMSD

root mean squared deviation

- TF

transferrin

- TLS

translation/liberation/screw motion)

References

- 1.Aisen P, Enns C, Wessling-Resnick M. Chemistry and biology of eukaryotic iron metabolism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:940–959. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason AB, Everse SJ. Iron transport by transferrin. In: Fuchs H, editor. Iron metabolism and disease. Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 2008. pp. 83–123. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang F, Lum JB, McGill JR, Moore CM, Naylor SL, van Bragt PH, Baldwin WD, Bowman BH. Human transferrcDNA characterization and chromosomal localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2752–2756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park I, Schaeffer E, Sidoli A, Baralle FE, Cohen GN, Zakin MM. Organization of the human transferrin gene: direct evidence that it originated by gene duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3149–3153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson BF, Baker HM, Dodson EJ, Norris GE, Rumball SV, Waters JM, Baker EN. Structure of human lactoferrin at 3.2 Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1769–1773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurokawa H, Mikami B, Hirose M. Crystal structure of diferric hen ovotransferrin at 2.4 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:196–207. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacGillivray RTA, Moore SA, Chen J, Anderson BF, Baker H, Luo YG, Bewley M, Smith CA, Murphy ME, Wang Y, Mason AB, Woodworth RC, Brayer GD, Baker EN. Two high-resolution crystal structures of the recombinant N-lobe of human transferrin reveal a structural change implicated in iron release. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7919–7928. doi: 10.1021/bi980355j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall DR, Hadden JM, Leonard GA, Bailey S, Neu M, Winn M, Lindley PF. The crystal and molecular structures of diferric porcine and rabbit serum transferrins at resolutions of 2.15 and 2.60 Å, respectively. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 2002;58:70–80. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901017309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Princiotto JV, Zapolski EJ. Difference between the two iron-binding sites of transferrin. Nature. 1975;255:87–88. doi: 10.1038/255087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lestas AN. The effect of pH upon human transferrselective labelling of the two iron-binding sites. Br J Haematol. 1976;32:341–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najarian RC, Harris DC, Aisen P. Oxalate and spin-labeled oxalate as probes of the anion binding site of human transferrin. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldwin DA, DeSousa DMR. The effect of salts on the kinetics of iron release from N-terminal and C-terminal monoferric transferrins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;99:1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)90732-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halbrooks PJ, He QY, Briggs SK, Everse SJ, Smith VC, MacGillivray RTA, Mason AB. Investigation of the mechanism of iron release from the C-lobe of human serum transferrmutational analysis of the role of a pH sensitive triad. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3701–3707. doi: 10.1021/bi027071q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker HM, Anderson BF, Brodie AM, Shongwe MS, Smith CA, Baker EN. Anion binding by transferrins: importance of second-shell effects revealed by the crystal structure of oxalate-substituted diferric lactoferrin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9007–9013. doi: 10.1021/bi960288y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun H, Li H, Sadler PJ. Transferrin as a metal ion mediator. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2817–2842. doi: 10.1021/cr980430w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert LA, Perri H, Meehan TJ. Evolution of the duplications in the transferrin family of proteins. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 2005;140:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert LA, Perri H, Halbrooks PJ, Mason AB. Evolution of the transferrin family: conservation of residues associated with iron and anion binding. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 2005;142:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang F, Lothrop AP, James NG, Griffiths TA, Lambert LA, Leverence R, Kaltashov IA, Andrews NC, Macgillivray RT, Mason AB. A novel murine protein with no effect on iron homeostasis is homologous to transferrin and is the putative inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase. Biochem J. 2007;406:85–95. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindskog S, Silverman DN. The catalytic mechanism of mammalian carbonic anhydrases. EXS. 2000;90:175–195. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8446-4_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman RB. The Organic Chemistry of Enzyme Catalyzed Reactions. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. Mechanisms of enzyme catalysis; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tashian RE. Genetics of the mammalian carbonic anhydrases. Adv Genet. 1992;30:321–356. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkkila S. An overview of the distribution and function of carbonic anhydrase in mammals. In: Chegwidden WR, Edwards Y, Carter N, editors. The carbonic anhydrases-new horizons. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag; 2000. pp. 79–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geers C, Gros G. Carbon dioxide transport and carbonic anhydrase in blood and muscle. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:681–715. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason AB, Judson GL, Bravo MC, Edelstein A, Byrne SL, James NG, Roush ED, Fierke CA, Bobst CE, Kaltashov IA, Daughtery MA. Evolution reversed: the ability to bind iron restored to the N-Lobe of the murine inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase by strategic mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9847–9855. doi: 10.1021/bi801133d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wuebbens MW, Roush ED, Decastro CM, Fierke CA. Cloning, sequencing, and recombinant expression of the porcine inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase: a novel member of the transferrin family. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4327–4336. doi: 10.1021/bi9627424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roush ED, Fierke CA. Purification and characterization of a carbonic anhydrase II inhibitor from porcine plasma. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12536–12542. doi: 10.1021/bi00164a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Booth VH. The carbonic anhydrase inhibitor in serum. J Physiol. 1938;91:474–489. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1938.sp003574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill EP. Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase by plasma of dogs and rabbits. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:191–197. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaeffer E, Lucero MA, Jeltsch JM, Py MC, Levin MJ, Chambon P, Cohen GN, Zakin MM. Complete structure of the human transferrin gene. Comparison with analogous chicken gene and human pseudogene. Gene. 1987;56:109–116. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose TM, Plowman GD, Teplow DP, Dreyer WJ, Hellström KE, Brown TP. Primary structure of the human melanoma-associated antigen p97 (melanotransferrin) deduced from the mRNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1261–1265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker EN, Baker HM, Smith CA, Stebbins MR, Kahn M, Hellström KE, Hellström I. Human melanotransferrin (p97) has only one functional iron-binding site. FEBS Lett. 1992;298:215–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80060-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekyere E, Richardson DR. The membrane-bound transferrin homologue melanotransferrroles other than iron transport? FEBS Lett. 2000;483:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekyere EO, Dunn LL, Richardson DR. Examination of the distribution of the transferrin homologue, melanotransferrin (tumour antigen p97), in mouse and human. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1722:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sekyere EO, Dunn LL, Rahmanto YS, Richardson DR. Role of melanotransferrin in iron metabolism: studies using targeted gene disruption in vivo. Blood. 2006;107:2599–2601. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wally J, Halbrooks PJ, Vonrhein C, Rould MA, Everse SJ, Mason AB, Buchanan SK. The crystal structure of iron-free human serum transferrin provides insight into inter-lobe communication and receptor binding. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24934–24944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604592200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barends TR, Dijkstra BW. Acetobacter turbidans alpha-amino acid ester hydrolase: merohedral twinning in P21 obscured by pseudo-translational NCS. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 2003;59:2237–2241. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903020729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delano WL. 2008. http://www.pymol.org The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific LLC, Palo Alto, CA, USA.

- 38.Baker EN, Baker HM. A structural framework for understanding the multifunctional character of lactoferrin. Biochimie. 2009;91:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milner-White EJ. Situations of gamma-turns in proteins. Their relation to alpha-helices, beta-sheets and ligand binding sites. J Mol Biol. 1990;216:386–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mason AB, Byrne SL, Everse SJ, Roberts SE, Chasteen ND, Smith VC, MacGillivray RT, Kandemir B, Bou-Abdallah F. A loop in the N-lobe of human serum transferrin is critical for binding to the transferrin receptor as revealed by mutagenesis, isothermal titration calorimetry, and epitope mapping. J Mol Recognit. 2009;22:521–529. doi: 10.1002/jmr.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He QY, Mason AB, Templeton DM. Molecular aspects of release of iron from transferrins. Molecular and cellular iron transport. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2002. pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacGillivray RTA, Mason AB, Templeton DM. Transferrins. Cell and molecular biology of iron transport. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2002. pp. 41–69. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jameson GB, Anderson BF, Norris GE, Thomas DH, Baker EN. Structure of human apolactoferrin at 2.0 A resolution. Refinement and analysis of ligand-induced conformational change. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 1998;54:1319–1335. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998004417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerstein M, Anderson BF, Norris GE, Baker EN, Lesk AM, Chothia C. Domain closure in lactoferrin. Two hinges produce a see-saw motion between alternative close-packed interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:357–372. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grossmann JG, Crawley JB, Strange RW, Patel KJ, Murphy LM, Neu M, Evans RW, Hasnain SS. The nature of ligand-induced conformational change in transferrin in solution. An investigation using X-ray scattering, XAFS and site-directed mutants. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:461–472. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mecklenburg SL, Donohoe RJ, Olah GA. Tertiary structural changes and iron release from human serum transferrin. J Mol Biol. 1997;270:739–750. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizutani K, Mikami B, Hirose M. Domain closure mechanism in transferrins: new viewpoints about the hinge structure and motion as deduced from high resolution crystal structures of ovotransferrin N-lobe. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:937–947. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rinaldo D, Field MJ. A computational study of the open and closed forms of the N-lobe human serum transferrin apoprotein. Biophys J. 2003;85:3485–3501. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74769-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang C, Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Open-to-closed transition in apo maltose-binding protein observed by paramagnetic NMR. Nature. 2007;449:1078–1082. doi: 10.1038/nature06232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bermejo GA, Strub MP, Ho C, Tjandra N. Ligand-free open-closed transitions of periplasmic binding proteins: the case of glutamine-binding protein. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1893–1902. doi: 10.1021/bi902045p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris WR, Wang Z, Brook C, Yang B, Islam A. Kinetics of metal ion exchange between citric acid and serum transferrin. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:5880–5889. doi: 10.1021/ic034009o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eyal E, Gerzon S, Potapov V, Edelman M, Sobolev V. The limit of accuracy of protein modeling: influence of crystal packing on protein structure. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dewan JC, Mikami B, Hirose M, Sacchettini JC. Structural evidence for a pH-sensitive dilysine trigger in the hen ovotransferrin N-lobe: implications for transferrin iron release. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11963–11968. doi: 10.1021/bi00096a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He QY, Mason AB, Tam BM, MacGillivray RTA, Woodworth RC. Dual role of Lys206-Lys296 interaction in human transferrin N-lobe: iron-release trigger and anion-binding site. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9704–9711. doi: 10.1021/bi990134t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halbrooks PJ, Giannetti AM, Klein JS, Bjorkman PJ, Larouche JR, Smith VC, MacGillivray RTA, Everse SJ, Mason AB. Composition of pH sensitive triad in C-lobe of human serum transferrin. Comparison to sequences of ovotransferrin and lactoferrin provides insight into functional differences in iron release. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15451–15460. doi: 10.1021/bi0518693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones EM, Smart A, Bloomberg G, Burgess L, Millar MR. Lactoferricin, a new antimicrobial peptide. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb03065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomita M, Takase M, Bellamy W, Shimamura S. A review: the active peptide of lactoferrin. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1994;36:585–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1994.tb03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mason AB, Halbrooks PJ, Larouche JR, Briggs SK, Moffett ML, Ramsey JE, Connolly SA, Smith VC, MacGillivray RTA. Expression, purification, and characterization of authentic monoferric and apo-human serum transferrins. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;36:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.James NG, Mason AB. Protocol to determine accurate absorption coefficients for iron containing transferrins. Anal Biochem. 2008;378:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In: Carter CW, Sweet RM, editors. Methods in enzymology, part A. San Diego: Academic Press; pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Padilla JE, Yeates TO. A statistic for local intensity differences: robustness to anisotropy and pseudo-centering and utility for detecting twinning. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 2003;59:1124–1130. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903007947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Collaborative Computational Project N. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, Delano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stein N. CHAINSAW: a program for mutating pdb files used as templates in molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 2008;41:641–643. [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Golinelli-Pimpaneau B. Structure of a pseudomerohedrally twinned monoclinic crystal form of a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent catalytic antibody. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 2005;61:472–476. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 2001;57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Altschul S, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thompson J, Higgins D, Gibson T. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of prgressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matriz choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nicholas KB, Nicholas HB, Deerfield DW., II GeneDoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. 1997 http://www.nrbsc.org/gfx/genedoc/ebinet.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. A neural network method for identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Int J Neural Syst. 1997;8:581–599. doi: 10.1142/s0129065797000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W609–W612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stern A, Doron-Faigenboim A, Erez E, Martz E, Bacharach E, Pupko T. Selecton 2007: advanced models for detecting positive and purifying selection using a Bayesian inference approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W506–W511. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abascal F, Zardoya R, Posada D. ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2104–2105. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]