Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including sulindac are well-documented to be highly effective for cancer chemoprevention. However, their cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitory activities cause severe gastrointestinal and cardiovascular toxicities, limiting their chronic use. Recent studies suggest that COX-independent mechanisms may be responsible for the chemopreventive benefits of the NSAIDs, and support the potential for development of a novel generation of sulindac derivatives lacking COX inhibition for cancer chemoprevention. A prototypic sulindac derivative with a N,N-dimethylammonium substitution, referred to as sulindac sulfide amide (SSA) was recently identified to be devoid of COX inhibitory activity yet displays much more potent tumor cell growth inhibitory activity in vitro compared to sulindac sulfide. In this study, we investigated the androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathway as a potential target for its COX-independent antineoplastic mechanism and evaluated its chemopreventive efficacy against prostate carcinogenesis using the TRAMP mouse model. The results showed that SSA significantly suppressed the growth of human and mouse prostate cancer cells expressing AR in strong association with G1 arrest, and decreased AR level and AR-dependent transactivation. Dietary SSA consumption from 6 to 24 weeks of age dramatically attenuated prostatic growth and suppressed AR-dependent glandular epithelial lesion progression via repressing cell proliferation in the TRAMP mice, whereas it did not significantly impact neuroendocrine carcinoma growth. Overall, the results suggest that SSA may be a chemopreventive candidate against prostate glandular epithelial carcinogenesis.

Keywords: sulindac derivative, COX, TRAMP, Androgen receptor

INTRODUCTION

One in six American men will be diagnosed in their lifetime with prostate carcinoma (PCa), which is the second leading cause of male cancer death in the United States (1). Available treatment options including surgery, hormone ablation, radiation and chemotherapy are not typically curative but only offer a temporary delay in the progression to hormone-refractory disease (2). Since prostate cancer has a long latency and progresses slowly, chemoprevention is considered as a highly plausible approach to reduce the incidence of this lethal disease through early intervention (3, 4).

Epidemiologic, laboratory and clinical studies have shown that the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including sulindac have promising chemopreventive efficacy against several types of carcinomas such as colon, breast, esophagus, stomach, lung, ovary and prostate (5–11). These nonselective NSAIDs possess cyclooxygenase (COX, including COX-1 and COX-2) inhibitory activities (12), which are generally considered to account for their chemopreventive efficacy (13–15). Long-term use of NSAIDs, however, including the selective COX-2 inhibitors (celecoxib and rofecoxib) has been linked to serious gastrointestinal, renal and/or cardiovascular side effects due to COX-1 and/or COX-2 inhibition, limiting their clinical use for chemoprevention (16–19). The pharmacological effects of NSAIDs are undoubtedly complex and may involve both COX-dependent and COX-independent mechanisms. Recent studies suggest that COX inhibition is ancillary for NSAIDs’ antineoplastic activities (20–23) and numerous mechanisms have been suggested to explain their chemopreventive benefits (24–27), though the precise molecular target(s) and mechanisms have not been well defined. Thus, it may be feasible to develop a novel generation of NSAID derivatives lacking COX inhibition for cancer chemoprevention and further studies to define their mechanism of action will help delineate the crucial activities and targets of this important drug class.

Sulindac is considered to be one of the most promising NSAIDs because of its ability to dramatically regress the colorectal adenomatous polyps in patients (28–31). SSA (Fig 1A) is a novel prototypic sulindac derivative and was specifically designed to replace the carboxylic acid with a positively charged N,N-dimethylethyl ammonium moiety to disrupt COX-1 and COX-2 binding (32). SSA displayed approximately 40 fold higher potency to inhibit the growth of human HT-29 colon tumor cells compared to the parent drug, sulindac sulfide (32). In addition, gastric gavage administration of SSA inhibited the growth of colon cancer xenografts in athymic mice that demonstrated in vivo evidence of antitumor activity (32). Earlier work with sulindac sulfone, an irreversible metabolite of sulindac, has shown a suppression of androgen receptor (AR) and its signaling in LNCaP prostate cancer cells (33). These results suggested the potential that SSA might prevent prostate carcinogenesis via novel COX-independent mechanism involving the suppression of androgen signaling.

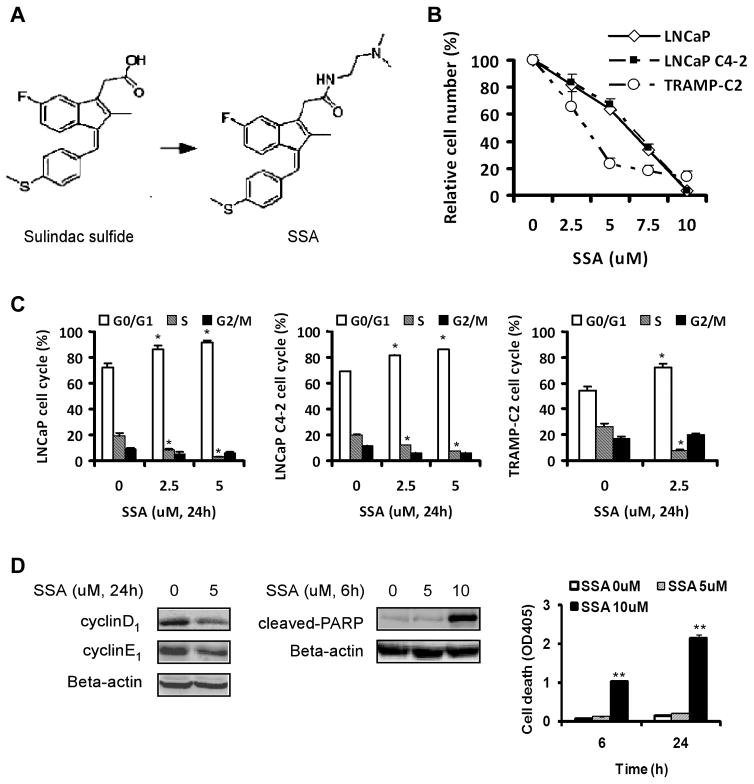

Fig. 1.

A, the chemical structure of sulindac sulfide and its N, N dimethylaminoethylamide derivative SSA. B, the growth inhibitory response curves of prostate cancer cells exposed to SSA for 48 h by crystal violet staining. Each point represents Mean ± SEM, n=3. C, cell cycle distribution of LNCaP, LNCaP C4-2 and TRAMP-C2 cells after 24h of SSA treatment. D, Suppression of cyclin D1 and cyclin E1 abundance after 24h of SSA treatment and, induction of cleaved-PARP and apoptotic nucleosomal fragmentation (Death ELISA) after 6 h or 24 h of SSA treatment in LNCaP cells. Flow cytometry experiments and ELISA were done in triplicate flasks. Statistical significance from control *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

The transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate (TRAMP) model, originally developed by Greenberg and colleagues is driven by the rat probasin promoter driven SV-40 T-antigen (T-Ag) expression (34). The TRAMP model is advantageous for chemoprevention studies compared to the commonly employed prostate cancer cell xenograft models because carcinogenesis occurs in situ from initiated cells in the transgenic mice, affording the opportunity to examine the action of chemopreventive agents on early stage lesions, whereas the xenograft models deal with frank cancer cells. Recent studies including our own have demonstrated that C57BL/6 TRAMP mice represent two distinct models of prostate carcinogenesis: one involving androgen receptor (AR)-dependent glandular epithelial lesions, and the other involving AR-independent neuroendocrine (NE)-like poorly differentiated carcinomas (35–37). The epithelial lesions, driven by AR-transactivated T-Ag expression, usually arise from the dorsal-lateral prostate (DLP) lobes, and progress in a step-wise manner from prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) to more advanced stage lesions. The epithelial lesions are characterized by the expression of AR and epithelial markers such as E-cadherin. In contrast, the NE-like lesions are driven by Foxa1- and/or Foxa2-transactivated (but not AR-transactivated) T-Ag, and usually originate from the ventral prostate (VP) lobe, expanding rapidly to large poorly differentiated (PD) carcinomas. The NE-like carcinomas are characterized by the expression of NE markers such as synaptophysin but AR and E-cadherin are absent (37). In the C57BL/6 background, the lifetime incidence of the NE-like PD carcinomas has been estimated to be 20%. The TRAMP mouse model is by far the most widely available and practical transgenic model for prostate cancer chemoprevention studies.

In the present study, we examined potential COX-independent antineoplastic targets of SSA, especially AR signaling pathway and mechanisms of action in prostate cancer cell lines, and evaluated its in vivo chemopreventive efficacy in TRAMP mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds

SSA was synthesized by Drs. R.C. Reynolds and G.A. Piazza (Southern Research Institute, Birmingham, AL) as reported recently (32). For the cell culture studies, SSA stock solution was prepared in DMSO and stored at −20°C. For the animal study, SSA was mixed with Teklad 2918 powder diet at Southern Research Institute and shipped overnight delivery to The Hormel Institute. The test diet was stored at 4°C.

Cell culture

The androgen-dependent human LNCaP cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and were cultured under the recommended conditions. The androgen-independent variant LNCaP C4-2 cells were a generous gift from Dr. Donald Tindall (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) and were cultured in the same condition as LNCaP cells. Both cell lines retain functional mutant AR. The mouse TRAMP-C2 cells were obtained from Dr. Michael Grossmann (The Hormel Institute, Austin, MN) and was cultured in ATCC recommended conditions. The TRAMP-C2 cells retain AR expression and highly proliferative as indicated by S-phase and G2 combined fractions of over 60%. All cells were maintained in their appropriate medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and were treated in the same medium supplemented with 1% FBS except when indicated otherwise. All the cells were maintained in the standard 37°C and 5% CO2 humidified environment.

Growth assay

Crystal violet staining of cellular proteins was used to evaluate the overall growth inhibitory effect of SSA on PCa cells as previously described (38). Briefly, the PCa cells were treated with SSA and vehicle control for 48h, and then the culture medium was removed and the cells remaining attached were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 15 min followed by staining with 0.02% crystal violet solution. After extensive washing with distilled water, the plates were air dried. The retained crystal violet dye was dissolved in 70% ethanol and the optical absorbance was measured at 570 nm with the reference 405 nm using a microplate reader (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Cell cycle distribution

Cells were exposed to SSA at indicated doses for 24 h, and then the cells were collected by trypsinization, and then the cell cycle distribution were analyzed by flowcytometry and PI staining as we previously reported (39).

Western blotting

The whole cell lysate and mouse tissue lysate were prepared and the western blots were done as previously described (37). Anti-E-Cadherin and cleaved-PARP were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-AR, anti-cyclinD1 anti-cyclin E1 and anti-PCNA were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-synaptophysin was obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Jose, CA). Anti-SV-40 T-antigen was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

Death ELISA for apoptotic DNA nucleosomal fragmentation

After exposure to SSA for 6h or 24h, the floating and attached cells were collected. The released oligonucleosomes after gentle lysis of the cells were quantified by Cell Death ELISA System double sandwich kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) as we previously described (38).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from LNCaP cells exposed to SSA or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 24h by using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total RNA (2 μg) from each sample was reverse transcribed by using Oligo-dT primers according to a reverse transcription Super Script™ II RT Kit manual (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 machine by using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Rox) system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and the primers of AR and PSA (Sigma-Genosys. The Woodlands, TX). Beta-actin was used as a normalizing control. The PCR condition was 1 cycle of 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, then 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95 °C, 1 min at 60 °C, then followed by 1 cycle of 15 sec at 95 °C, 1 min at 60 °C, 15′ at 95 °C, 15′ at 60 °C referred to previously described (40). AR primers: Forward 5′-CAG GAG GAA GGA GAG GCT TC-3′, Reverse 5′-AGC AAG GCT GCA AAG GAG TC-3′. PSA primers: Forward: 5′-CCC ACT GCA TCA GGA ACA AA-3′, Reverse: 5′-GAG CGG GTG TGG GAA GCT-3′

Stable transfection and luciferase reporter assay

LNCaP cells were seeded and allowed to grow to 80–90% confluence. Transfection of PSA-luc was carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as previously described (41). PSA-luc is a luciferase reporter driven by a six-kb PSA promoter (kindly provided by Dr. Charles Young, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). After two weeks of selection with G418 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), the cells stably expressing PSA-luc were amplified and referred to as LN-PSA-luc. Luciferase reporter assay was carried out as previously described (42). Briefly, the cells were seeded in complete growth medium and were allowed to grow to 40–50% confluence, and then were fed phenol red-free RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped serum for 24h. The cells were treated with 0.5nM mibolerone (kindly provided by Dr. Charles Young, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) alone or combined with indicated doses of SSA in phenol red-free RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped serum for another 24h. Decursin at 10uM was used as a positive control as previously described (43, 44). The whole cell lysate was processed according to the Promega Luciferase System protocol (Promega Corp, Madison, WI) and was analyzed using a Luminoskan (Thermo Electron Corporation, Milford, MA). The luciferase activity was normalized to protein concentration.

Chemoprevention study of spontaneous carcinogenesis in TRAMP mice

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Minnesota, and carried out at the Hormel Institute’s AAALAC-accredited animal facility. The C57BL/6 TRAMP mice were bred and genotyped as previously described (37). Forty-one (six weeks old) male C57BL/6 TRAMP mice were randomly divided into 2 groups and fed Teklad 2918 powder diet without supplement (n=21) or that diet supplemented with 2000ppm SSA (n=20), as were seventeen wild type male mice (n=8 or n=9, respectively). The choice of 2000 ppm dosage was based on a feeding experiment in which this dosage was effective against colonic carcinogenesis in FCCC Min transgenic mice (Dr. Margie Clapper, Fox Chase Cancer Center, unpublished data). The male mice were housed individually to prevent fighting and aggression-related complications. All the mice were monitored daily and weighed weekly, and euthanized at 24 weeks of age except for two that had to be killed early (21 and 23 weeks of age) because of large tumor burden. Blood was collected prior to euthanasia for serum preparation. The lower genital urinary (GU) tract, including seminal vesicle, prostate, testes and bladder was dissected and weighed. The dorsal-lateral prostate (DLP) lobes, ventral prostate (VP) lobes, large tumors and swollen lymph nodes were carefully dissected and weighed. A portion of the specimen was fixed for 24 hours in 10% (v/v) neutral-buffer formalin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and stored in 70% ethanol until processing for histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC). The other portion was frozen on dry ice and stored at −70°C for later molecular biomarker analyses.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

H&E and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining were routinely performed as described previously (37). Briefly, the prostate tissues and tumors were processed, and the paraffin embedded sections (4 μm thickness) were used for H&E and IHC staining. The anti-AR (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA), anti-E-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and anti-synaptophysin (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA) were diluted in PBS supplemented with 1%BSA at 1:400, 1:400 and 1:150, respectively. The lesions were quantified based on the percentage of different stages of lesions within each slide based on the published classifying criteria (35, 36, 45).

Measurement of SSA and sulindac sulfide levels in serum

Mice were bled on the day of sacrifice within 4 hours of the onset of the light cycle in the morning. Serum was processed and analyzed for SSA and sulindac sulfide levels using reverse phase chromatography (Perkin-Elmer Series 200 autosampler and micropumps) with MS/MS (Perkin-Elmer Sciex API 3000) detection operating in the positive ion mode using multiple reaction monitoring as described previously (32).

Statistical analyses

Results were analyzed by ANOVA or t-test to determine the statistical significance among or between the specific groups.

RESULTS

1. SSA inhibited the growth of human and mouse prostate cancer cells in vitro with enhanced potency compared to sulindac

Since prostate adenocarcinomas arise from AR-expressing cells, we determined the potency of SSA to inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cells expressing AR. These included human LNCaP and its variant LNCaP C4-2 cells and mouse TRAMP-C2 (derived from a prostate tumor of a TRAMP mouse). After exposure to SSA for 48h, the number of cells remaining attached was measured by crystal violet staining of cellular proteins. As shown in Fig 1B, SSA decreased the number of human PCa cells in a dose-dependent manner with a GI50 of ~6 μM. The mouse TRAMP-C2 cells were suppressed to even a greater extent, with GI50 of ~3 μM, probably due to much faster growth than the human cells. The growth suppressing potency of SSA on prostate cancer cells was comparable to that of colon tumor cells as previously reported and was at least an order of magnitude higher than sulindac sulfide (32).

2. SSA inhibited the proliferation of prostate cancer cells associated with an induction of G1 arrest

Since SSA displays potent PCa cell growth inhibitory activity, but is devoid of COX-1 or COX-2 inhibitory activity (32), we sought to investigate the cellular mechanism for its COX-independent antineoplastic activity by determining its effects on cell cycle progression and apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 1C, SSA caused a concentration-dependent increase in the percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase with a reduction of cells in S phase in both the LNCaP and LNCaP C4-2 cell lines, which is indicative of an induction of G1 arrest. The TRAMP-C2 cells contained much higher S and G2 fractions compared with the human cells and showed G1 arrest upon SSA exposure (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, SSA treatment decreased cyclin D1, one of the crucial cyclins needed to activate CDK4/6 to promote G1 progression and cyclin E1, which activates CDK2 to enable G1/S transition (Fig. 1D). At higher exposure levels, SSA induced caspase-mediated apoptosis of prostate cancer cells after a treatment of 6h and 24h as indicated by increased PARP cleavage and increased DNA oligonucleosomal fragmentation detected by Death ELISA (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these data suggested that SSA inhibited the in vitro growth of prostate cancer cells by G1 arrest, as well as the induction of apoptosis.

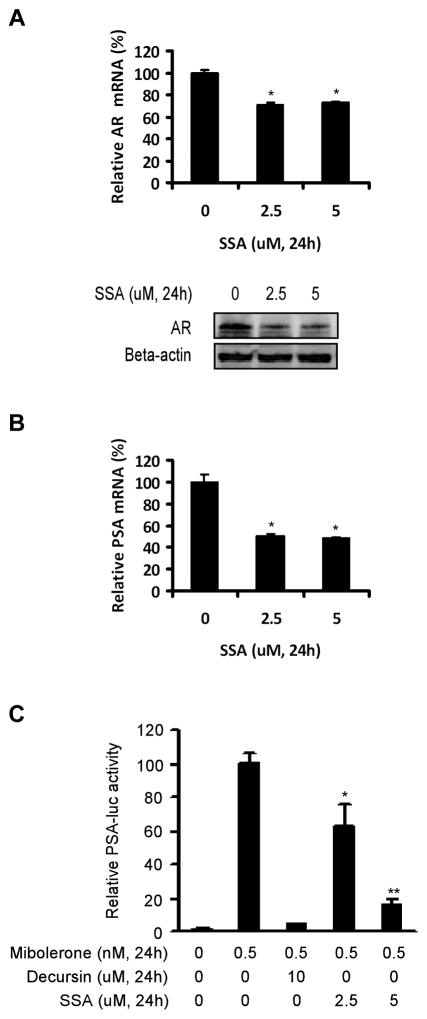

3. SSA down-regulated AR and suppressed AR-dependent transactivation in prostate cancer cells

Since AR is indispensable for the G1/S transition and proliferation of the androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells (46, 47) and sulindac sulfone, an irreversible metabolite of sulindac, has been shown to inhibit AR signaling (33), we were interested in whether AR signaling was affected by SSA treatment. As shown in Fig 2A, both AR mRNA and protein levels were decreased by SSA in LNCaP C4-2 cells after 24h of treatment. SSA treatment decreased mRNA level of PSA, which is an endogenous target of AR-dependent transactivation (Fig 2B). SSA also inhibited PSA expression in LNCaP cells (data not shown). Furthermore, a luciferase reporter driven by a six-kb human PSA promoter was dose-dependently inhibited by SSA in LNCaP cells (Fig 2C), providing direct evidence of SSA’s inhibitory activity on AR-dependent transactivation. Taken together, these data demonstrated that SSA suppressed AR signaling, as manifested by PSA, at least in part via a down-regulation of AR level in prostate cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

SSA suppresses AR expression and antagonizes AR signaling in human prostate cancer cells. A, Down regulation by 24 h of SSA treatment of both AR mRNA (top panel, real-time PCR) and AR protein (bottom panel, western-blot) levels in LNCaP C4-2 cells. The mRNA levels were normalized to those of the vehicle controls. B, Suppression by 24 h of SSA treatment of PSA mRNA level (real-time PCR) in LNCaP C4-2 cells. The mRNA levels were normalized to those of the vehicle controls. C, dose-dependent inhibition of PSA-luc reporter in LNCaP cells by SSA treatment for 24h. The luciferase activities were normalized to protein concentration, and then were converted into the relative folds to the mibolerone-stimulated control. Mibolerone is a stable analogue of dihydrotestosterone. Decursin is an inhibitor of AR signaling used as a positive control (44). PSA-luc is a luciferase reporter driven by a six-kb human PSA promoter. The assays of real-time PCR and luciferase reporter were done in triplicate. Statistical significance from control *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

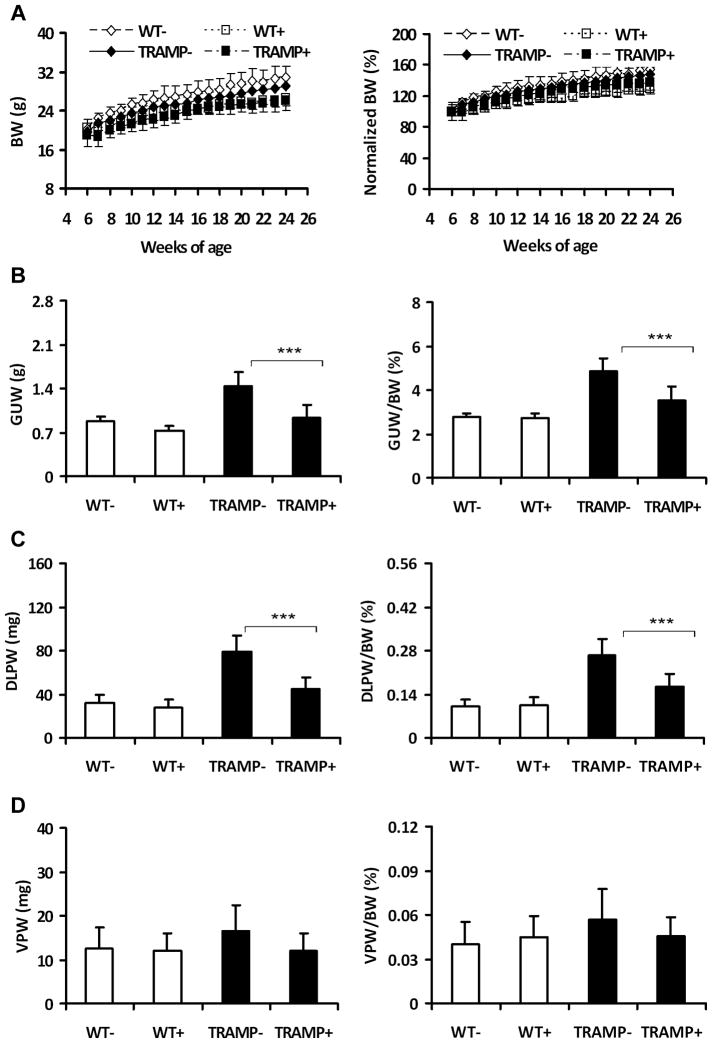

4. SSA treatment suppressed dorsolateral prostatic growth (weight) in the TRAMP mice

Encouraged by the in vitro results, we evaluated the in vivo chemopreventive efficacy of SSA using the TRAMP mouse as a primary prostate carcinogenesis model (34). The weights of GU tracts and DLP lobes are commonly used as gross parameters of prostatic carcinogenesis in TRAMP mice (34, 45). Consumption of SSA from 6–24 weeks of age decreased the body weights of TRAMP and wild-type mice by 5.6% and 16.2%, respectively (Fig 3A). To correct for the difference due to body weight, the GU tract, DLP and VP weights were normalized against the endpoint body weights (Fig 3B, C and D). Consumption of SSA at 2000 ppm in the diet significantly repressed both the actual and relative weight increments of the GU tracts of TRAMP mice (Fig. 3B) by 64.1% and 63.7% (p<0.001 and p<0.001), respectively, in reference to their baseline weight in the age-matched wild type mice. SSA also significantly decreased those of the DLP lobes of TRAMP mice by 64.0% and 61.9% (p<0.001 and p<0.001), respectively (Fig 3C). SSA numerically reversed the increased VP weights (20~30% greater than those of the wild type mice) of TRAMP mice to the level of wild type mice (Fig 3D) (not statistically significant).

Fig. 3.

Effect of dietary SSA on the body weight and genital urinary (GU) tract weights in TRAMP and wild type mice. WT−, wild type mice without SSA supplement (n=8); WT+, wild type mice with 2000ppm SSA (n=9); TRAMP−, TRAMP mice without SSA supplement (n=20); TRAMP+, TRAMP mice with 2000ppm SSA (n=18). A, Growth curves of mice based on the actual (left panel) and normalized body weight to initial weight at enrollment (right panel). BW: body weight. Normalized BW: body weight was normalized against the initial enrollment body weight (as 100%). B, C and D, the actual (left panels) and relative weights of the GU tracts, DLP lobes and VP lobes, respectively. GUTW: GU tract weight. DLPW: DLP lobe weight. VPW: VP lobe weight. GUTW/BW, DLPW/BW and VPW/BW: the relative weights of GU tract, DLP lobe and VP lobe, which were normalized against the endpoint body weight, respectively, and shown as %. ANOVA test was used to determine the significance among the groups. Statistical significance from TRAMP(−) group, ***p <0.001.

It is noteworthy that three mice with large tumors, one weighing 7.11g from the control group, and the other two weighing 1.59g and 2.59g from the SSA fed group, were excluded from the above analyses. These tumors were much larger compared to the whole prostates and they arose from a lineage different (confirmed later as NE-like carcinomas (See Fig. 4 and 5) from the DL prostate glandular epithelial lesions.

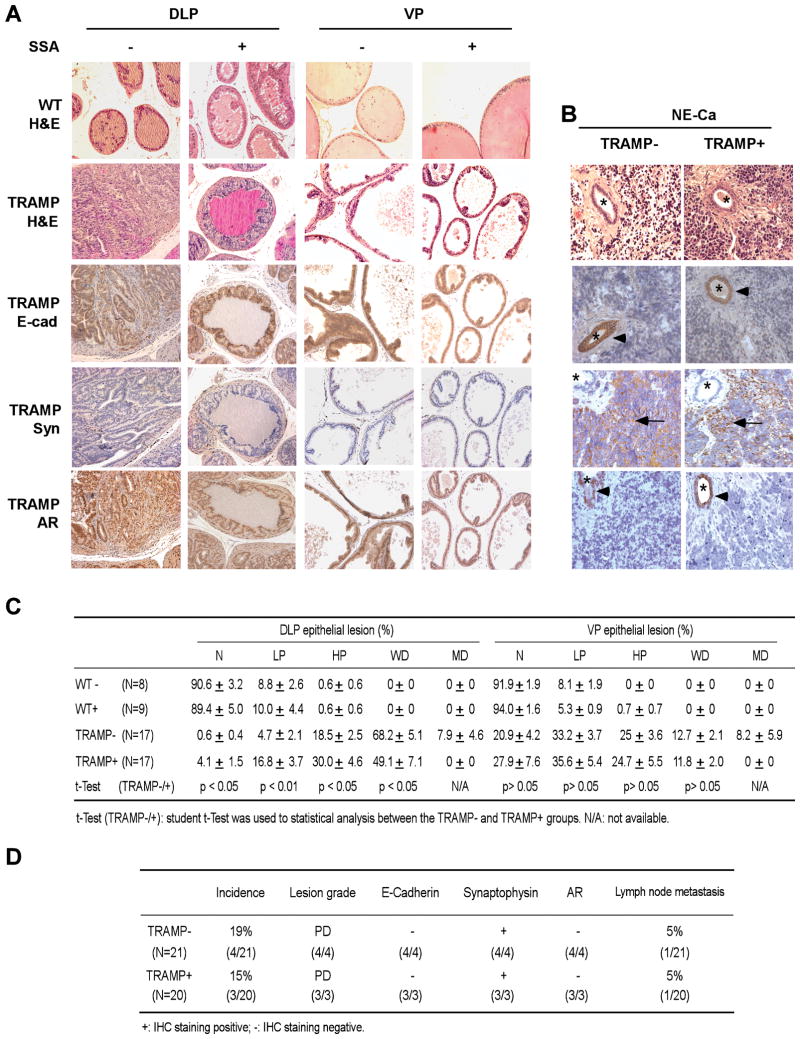

Fig. 4.

Histopathological evaluation of the effects of dietary SSA consumption on the TRAMP epithelial lesions and NE-like carcinomas. A, Typical AR-dependent glandular epithelial lesions in the DLP and VP lobes of the TRAMP vs. histology of the wild type mice (magnification, 200x). IHC staining: E-cad, E-cadherin; Syn, synaptophysin; AR, androgen receptor. B, typical AR-negative NE-carcinomas. All the NE-like lesions were poorly differentiated (PD) lesions, synaptophysin-positive (arrow), but absent of E-cadherin and AR. The trapped glands (*) were E-cadherin- and AR-positive (arrow head), but absent of synaptophysin. C, Distribution patterns of the AR-dependent glandular epithelial lesions among the specific groups. WT−, wild type mice without SSA supplement (n=8); WT+, wild type mice with 2000ppm SSA (n=9); TRAMP−, TRAMP mice without SSA supplement (n=17); TRAMP+, TRAMP mice with 2000ppm SSA (n=17). N: normal; LP: low grade PIN (prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia), HP: high grade PIN, WD: well-differentiated carcinoma, MD: moderate-differentiated carcinoma. Mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from TRAMP(−) group was calculated by 2-tailed t-test. D, Summary of the AR-independent NE-carcinomas and metastases. PD, poorly differentiated carcinoma.

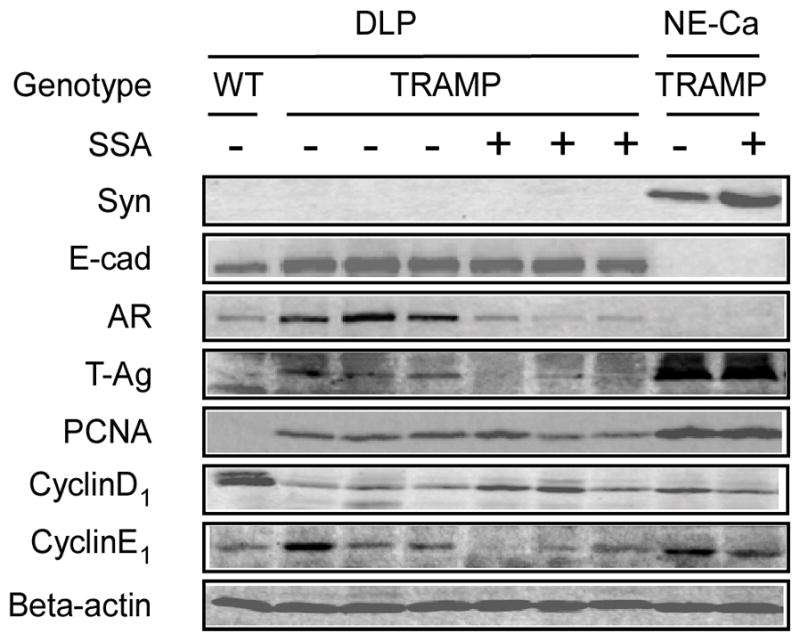

Fig. 5.

Western blot analyses of effects of SSA on molecular biomarkers in TRAMP. DLP and NE-Ca: DLP lobes and NE-like carcinomas. WT: wild type mice, TRAMP+: SSA supplemented TRAMP mice. Syn: synaptophysin, E-cad: E-cadherin

Dietary consumption of SSA did not affect the actual and relative weights of the GU tracts (p>0.05), DLP lobes (p>0.05) and VP lobes (p>0.05) of wild type mice (Fig 3B, C and D). Taken together, these data show that dietary SSA consumption repressed the T-Ag driven dorsolateral prostatic growth in the TRAMP mice without an evident inhibition of the rapid growing, poorly-differentiated carcinomas, which are characterized as NE-carcinomas by synaptophysin expression (See below).

5. SSA treatment retarded the AR-expressing glandular epithelial lesions but not AR-negative NE-carcinomas

To further verify the chemopreventive efficacy of SSA in vivo, the DLP lobes, VP lobes and tumors were processed for histopathological analyses. We distinguished both AR-dependent glandular epithelial lesions and AR-independent poorly differentiated NE-carcinomas/lesions by the differential expression patterns of AR and E-cadherin vs. synaptophysin (Fig 4A vs. B and Fig 5). In addition to the three large NE-like carcinomas, four microscopic NE-like lesions (three from the control group and one from the SSA supplement group) were found in the VP lobes (Fig. 4D). The overall NE-lesion incidence (17.1%, 7 out of 41 mice) was similar to the previous reports (approximate 20%) of C57BL/6 TRAMP mice (35, 36). We excluded these mice from the histological analyses of the DLP and VP epithelial lesions to eliminate potential confounding effect of NE-carcinoma on these epithelial lesions in the same mice. One lymph node metastasis was found in each group (Fig. 4D), verified by the presence of T-Ag and absence of AR staining by IHC (not shown).

Dietary SSA consumption increased the percentage of normal and/or lower grade lesions (low grade and high grade PINs), but decreased that of the well-differentiated and moderately differentiated adenocarcinomatous lesions in the DLP lobes (Fig 4A and C). SSA did not significantly impact the lesion distribution patterns in the VP lobes (Fig 4A and C). SSA did not affect the incidence of NE-like lesions (Fig 4B and D). The histology of the normal DLP and VP lobes of the wild type mice was not affected by SSA (Fig 4A and C). Taken together, these histopathological data suggest that SSA delayed the progression of the AR-expressing glandular epithelial lesions but did not affect the AR-negative NE-lesions/carcinomas in the TRAMP mice.

6. Dietary SSA down-regulated biomarkers of cell proliferation in the TRAMP mice

To delineate the molecular effectors of SSA in vivo, we randomly selected several DLP samples and NE carcinomas for Western-blot analyses. Consistent with the immunohistochemistry results, E-cadherin and AR were detected in the DLP of the TRAMP mice and also in the wild type mice, albeit much lower levels, but were undetectable in the NE-carcinomas. In contrast, synaptophysin was detected in the NE carcinomas, which expressed massive amount of T-Ag, but was absent in the DLP (Fig 5). Compared to TRAMP mice receiving the control diet, dietary SSA consumption suppressed AR and T-Ag signals in the DLP lobes of TRAMP mice. In addition, SSA decreased PCNA (a proliferation marker) and cyclin E1 (a crucial cyclin for G1/S transition and proliferation in TRAMP mice) in the DLP of TRAMP mice. Interestingly, the cyclin D1 level was significantly reduced in the TRAMP DLP when compared to the wild type DLP and this loss was attenuated in the SSA-treated TRAMP DLP. SSA did not significantly affect those in the NE carcinomas, which lacked the expression of AR. Furthermore, we did not detect increased cleavage of PARP, an apoptosis marker of caspase-activation, in the DLP of SSA-supplemented TRAMP mice compared to the DLP from control TRAMP mice (data not shown). The lack of in vivo pro-apoptosis activity emphasized the primary role of anti-proliferative activity of SSA in retarding the prostatic glandular epithelial lesion progression. Taken together, these data suggest that SSA suppressed epithelial cell proliferation and lesion progression in TRAMP mice associated with AR signaling inhibition.

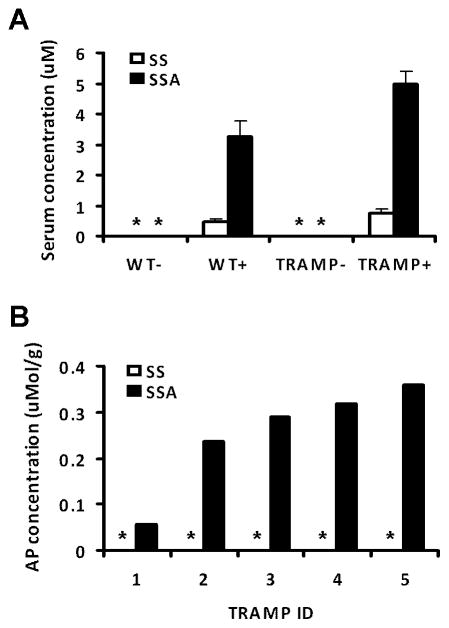

7. Dietary consumption led to elevated serum SSA level and prostate tissue accumulation

Measurement of serum SSA and sulindac sulfide of 5 mice randomly picked from each group showed that feeding from 6 to 24 weeks of age resulted in average serum SSA level of 3.3 and 4.9 μM in the WT mice and TRAMP mice, respectively (Fig 6A). Only a low level of sulindac sulfide at 0.4 and 0.7 μM (Fig 6A) was detected in WT and TRAMP mice, respectively. This indicates that SSA was not converted to the parent compound. Measurement of the anterior prostate lobe of TRAMP mice for SSA indicated approximately 250 ± 5 (SEM, n = 5 mice) nmol/g wet tissue, whereas sulindac sulfide was not detectable (Fig 6B). These results therefore support the attainment of lower micromolar levels of serum SSA in mice fed SSA with minimal back conversion to sulindac sulfide and the accumulation of SSA in the prostate tissue over the blood level (~50 fold).

Fig. 6.

Detection of SSA and its back conversion product sulindac sulfide in (A) serum, mean ± SEM, N = 5 and (B) in anterior prostate gland, each bar represents an individual mouse. * indicates below limit of detection.

DISCUSSION

The lack-luster performance of chemotherapy for advanced recurrent prostate cancer that has failed hormone ablation, surgery, and radiation calls for new approaches to combat this disease at its early stages. The long latency period and high prevalence of prostate cancer in men make chemoprevention of prostate carcinogenesis an attractive strategy to manage this disease by attacking it at its root.

In the present study, we demonstrated that SSA, a novel non-COX inhibitory derivative of sulindac significantly suppressed the growth of human and mouse prostate cancer cells expressing AR in vitro in strong association with G1 arrest at the lower micromolar levels of exposure and caspase-mediated apoptosis at higher concentrations (≥ 10 μM). In vivo, dietary consumption of SSA led to the achievement of 4~5 μM SSA with little back conversion to sulindac sulfide (Fig. 6) and the attainment of 250 nmol SSA/g wet prostate tissue (~250 μM). Interestingly, SSA feeding retarded the AR-expressing epithelial spontaneous carcinogenesis in the TRAMP mice without evident efficacy against AR-negative NE-carcinoma development (Fig. 4–5). There was no increased apoptosis in the SSA-supplemented DLP compared to the control DLP. Given that NE-carcinomas arise de novo from the ventral prostate, not from trans-differentiation and progression of the AR-expressing DLP lesions (35, 36), our data suggest that anti-proliferative effect might play a primary role in mediating the in vivo efficacy of SSA against the susceptible target AR-expressing epithelial cells in our chosen model.

Concerning molecular targets and mechanisms of action, we demonstrated in vitro that SSA decreased AR level and suppressed AR dependent transactivation in prostate cancer cell culture models. It has been firmly established that AR plays an essential and critical role in the cell cycle progression and proliferation of androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells (46, 47). Some cell cycle regulators are the direct or indirect targets of AR-dependent transactivation, and AR silencing and/or androgen deprivation primarily block G1/S transition and progression (46, 47). Consistent with the cell culture results on AR suppression and signaling inhibition, we detected decreased AR abundance in the DLP of SSA-fed TRAMP mice by Western blot analyses. We also detected by Western blot the decreased expression of the T-Ag, which is mediated by AR transactivating the rat probasin promoter. We observed decreased cyclin E1 and PCNA in the SSA-DLP samples, but no decrease of cyclin D1. While the in vivo data do not allow a definitive establishment of cause-effect among the affected proteins, one scenario is that an inhibition of AR expression and signaling by SSA may result in a decreased expression of T-Ag because the probasin promoter/T-Ag transgene is AR-driven, and this in turn decreased the bound form of Rb to T-Ag, freeing up Rb to suppress E2F transcription of cyclin E1, leading to a blockage at the G1/S transition. Corroborating this scenario, in the NE-cells where high level T-Ag expression is not driven by AR, SSA was not active to suppress their in vivo growth. These data suggest an anti-proliferative action of SSA through cyclin E1-related CDKs in vivo to inhibit AR-dependent glandular epithelial lesion progression. Alternatively, SSA consumption could inhibit epithelial cell proliferation, decreasing the proportion of AR- and T-Ag-expressing cells in the DLP gland. Consistent with this alternative scenario, IHC detection of AR expression at the cellular level did not show less staining intensity on a per cell basis for SSA-treated DLP vs. control DLP (Fig. 4). Clearly, more detailed analyses of the relevant molecular targets and cellular pathways are crucial to resolve these issues.

Although we found cyclin D1 suppression by SSA in cell culture, this cyclin is lost over the course of lesion progression in the TRAMP model as evident in Fig. 5 when compared to wild type DLP, consistent with the “cyclin switch” reported by Greenberg’s lab (48). The down regulation of cyclin D1 in the SSA-treated TRAMP DLP in comparison with control TRAMP is therefore consistent with retarded epithelial lesion progression and highlights a difference between the TRAMP model and human cancer cells.

We should note that SSA exerted some adverse effect on body weight in TRAMP and wild type mice (Fig. 3A), implying a possible narrow window between chemoprevention and safety. The athymic nude mice receiving gavage of SSA (250 mg/kg, bid, P.O.) displayed good tolerance and efficacy against colon cancer xenografts (32). We could not exclude the potential effect of different genetic backgrounds of the mice on their tolerance to SSA, nor dosing regimens. More studies with different strains of mice and GLP grade product will be helpful to address this issue.

Overall, this study suggests the feasibility of developing a novel generation of sulindac derivatives lacking COX inhibition for prostate cancer chemoprevention. We showed that SSA inhibited prostate glandular epithelial lesion growth and progression, at least in part via suppression of cell proliferation. SSA did not display efficacy against AR-negative NE-carcinomas in this model, suggesting a potential selectivity of the compound on AR signaling. Additional studies using preclinical models of prostate adenocarcinogenesis without the complication of NE-carcinogenesis of the TRAMP model are necessary and essential to validate the efficacy and survival benefit of this novel sulindac derivative, as well as other analogs that may have potency and/or bioavailability advantages to provide compelling rationales for future translational consideration.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Lori Coward and Dr. Greg Gorman for analysis of SSA and sulindac levels in mouse serum samples. We express sincere gratitude to Ellen Kroc and her staff in the Hormel Institute animal facility for excellent help with the feeding study.

Funding supports: In parts by Hormel Foundation, National Cancer Institute Grants R01CA95642 and R01CA131378

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest:

All authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrylak DP. The current role of chemotherapy in metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Urology. 2005;65(5 Suppl):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.03.053. discussion -8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein EA. Can prostate cancer be prevented? Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2005;2(1):24–31. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parnes HL, Thompson IM, Ford LG. Prevention of hormone-related cancers: prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(2):368–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrawal A, Fentiman IS. NSAIDs and breast cancer: a possible prevention and treatment strategy. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(3):444–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Sitaras NM. Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs affect the risk of developing ovarian cancer? A meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60(2):194–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasgupta K, Di Cesar D, Ghosn J, Rajan R, Mahmud S, Rahme E. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostate cancer occurrence. Cancer J. 2006;12(2):130–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan L, Wu AH, Sullivan-Halley J, Bernstein L. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas in Los Angeles County. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(1):126–34. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez-Diaz S, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(7):1565–72. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ, Bain EB, Rodriguez C, Henley SJ, Calle EE. A large cohort study of long-term daily use of adult-strength aspirin and cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(8):608–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Patrono C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as anticancer agents: mechanistic, pharmacologic, and clinical issues. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(4):252–66. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.4.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith WL, Meade EA, DeWitt DL. Interactions of PGH synthase isozymes-1 and -2 with NSAIDs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;744:50–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb52723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arber N, Eagle CJ, Spicak J, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):885–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron JA, Sandler RS, Bresalier RS, et al. A randomized trial of rofecoxib for the chemoprevention of colorectal adenomas. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1674–82. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):873–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace JL. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastroenteropathy: the second hundred years. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(3):1000–16. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1092–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerr DJ, Dunn JA, Langman MJ, et al. Rofecoxib and cardiovascular adverse events in adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):360–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1071–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piazza GA, Alberts DS, Hixson LJ, et al. Sulindac sulfone inhibits azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in rats without reducing prostaglandin levels. Cancer Res. 1997;57(14):2909–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoner GD, Budd GT, Ganapathi R, et al. Sulindac sulfone induced regression of rectal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;470:45–53. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4149-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arber N, Kuwada S, Leshno M, Sjodahl R, Hultcrantz R, Rex D. Sporadic adenomatous polyp regression with exisulind is effective but toxic: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, dose-response study. Gut. 2006;55(3):367–73. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.061432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duggan DE, Hooke KF, Noll RM, Hucker HB, Van Arman CG. Comparative disposition of sulindac and metabolites in five species. Biochem Pharmacol. 1978;27(19):2311–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(78)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babbar N, Ignatenko NA, Casero RA, Jr, Gerner EW. Cyclooxygenase-independent induction of apoptosis by sulindac sulfone is mediated by polyamines in colon cancer. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278(48):47762–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karl T, Seibert N, Stohr M, Osswald H, Rosl F, Finzer P. Sulindac induces specific degradation of the HPV oncoprotein E7 and causes growth arrest and apoptosis in cervical carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2007;245(1–2):103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice PL, Kelloff J, Sullivan H, et al. Sulindac metabolites induce caspase- and proteasome-dependent degradation of beta-catenin protein in human colon cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2(9):885–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wick M, Hurteau G, Dessev C, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs mediating cyclooxygenase-independent inhibition of lung cancer cell growth. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62(5):1207–14. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giardiello FM, Hamilton SR, Krush AJ, et al. Treatment of colonic and rectal adenomas with sulindac in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(18):1313–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuhashi N, Nakajima A, Fukushima Y, Yazaki Y, Oka T. Effects of sulindac on sporadic colorectal adenomatous polyps. Gut. 1997;40(3):344–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuhashi N, Nakajima A, Shinohara K, Oka T, Yazaki Y. Rectal cancer after sulindac therapy for a sporadic adenomatous colonic polyp. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(11):2261–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nugent KP, Farmer KC, Spigelman AD, Williams CB, Phillips RK. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of sulindac on duodenal and rectal polyposis and cell proliferation in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1993;80(12):1618–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800801244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piazza GA, Keeton AB, Tinsley HN, et al. A novel sulindac derivative that does not inhibit cyclooxygenases but potently inhibits colon tumor cell growth and induces apoptosis with antitumor activity. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2009;2(6):572–80. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim JT, Piazza GA, Pamukcu R, Thompson WJ, Weinstein IB. Exisulind and related compounds inhibit expression and function of the androgen receptor in human prostate cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(13):4972–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenberg NM, DeMayo F, Finegold MJ, et al. Prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(8):3439–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiaverotti T, Couto SS, Donjacour A, et al. Dissociation of epithelial and neuroendocrine carcinoma lineages in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model of prostate cancer. The American journal of pathology. 2008;172(1):236–46. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huss WJ, Gray DR, Tavakoli K, et al. Origin of androgen-insensitive poorly differentiated tumors in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model. Neoplasia. 2007;9(11):938–50. doi: 10.1593/neo.07562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Bonorden MJ, Li GX, et al. Methyl-selenium compounds inhibit prostate carcinogenesis in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model with survival benefit. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2009;2(5):484–95. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu H, Jiang C, Ip C, Rustum YM, Lu J. Methylseleninic acid potentiates apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs in androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(6):2379–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malewicz B, Wang Z, Jiang C, et al. Enhancement of mammary carcinogenesis in two rodent models by silymarin dietary supplements. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(9):1739–47. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitzgerald JB, Jin M, Dean D, Wood DJ, Zheng MH, Grodzinsky AJ. Mechanical compression of cartilage explants induces multiple time-dependent gene expression patterns and involves intracellular calcium and cyclic AMP. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279(19):19502–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400437200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu H, Zhang J, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Lu J. Penta-O-galloyl-beta-D-glucose induces S- and G(1)-cell cycle arrests in prostate cancer cells targeting DNA replication and cyclin D1. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(5):818–23. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang F, Ezell SJ, Zhang Y, et al. FBA-TPQ, a novel marine-derived compound as experimental therapy for prostate cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9232-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo J, Jiang C, Wang Z, et al. A novel class of pyranocoumarin anti-androgen receptor signaling compounds. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(3):907–17. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang C, Lee HJ, Li GX, et al. Potent antiandrogen and androgen receptor activities of an Angelica gigas-containing herbal formulation: identification of decursin as a novel and active compound with implications for prevention and treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(1):453–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaplan-Lefko PJ, Chen TM, Ittmann MM, et al. Pathobiology of autochthonous prostate cancer in a pre-clinical transgenic mouse model. The Prostate. 2003;55(3):219–37. doi: 10.1002/pros.10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comstock CE, Knudsen KE. The complex role of AR signaling after cytotoxic insult: implications for cell-cycle-based chemotherapeutics. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex. 2007;6(11):1307–13. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.11.4353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Q, Li W, Zhang Y, et al. Androgen receptor regulates a distinct transcription program in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cell. 2009;138(2):245–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maddison LA, Huss WJ, Barrios RM, Greenberg NM. Differential expression of cell cycle regulatory molecules and evidence for a “cyclin switch” during progression of prostate cancer. The Prostate. 2004;58(4):335–44. doi: 10.1002/pros.10341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]