Abstract

The management of patients with asymptomatic carotid disease is currently under debate and new methods are warranted for better risk stratification. The role of the biomechanical properties of the atherosclerotic arterial wall together with the effect of different stress types in plaque destabilisation has only been recently investigated. PubMed and Scopus databases were reviewed. There is preliminary clinical evidence demonstrating that the analysis of the combined effect of the various types of biomechanical stress acting on the carotid plaque may help us to identify the vulnerable plaque. At present, MRI and two-dimensional ultrasound are combined with fluid–structure interaction techniques to produce maps of the stress variation within the carotid wall, with increased cost and complexity. Stress wall analysis can be a useful tool for carotid plaque evaluation; however, further research and a multidisciplinary approach are deemed as necessary for further development in this direction.

The mid-term overall risk reduction with carotid endarterectomy (CEA) in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis is minimal. The Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study [1] reported that in patients with stenosis >60% CEA reduced the annual risk of stroke from 2% to 1%, which implies that approximately 20 procedures need to be performed to prevent one stroke in five years. For this reason, there is considerable debate about how appropriate this procedure is for all patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis, and restriction to patients who are at high risk of developing neurological events might be more cost-effective.

There has been considerable effort to develop new diagnostic algorithms that will enable physicians to distinguish between high- and low-risk patients according to the degree of stenosis of carotid lumen [2, 3], the intima–media thickness (IMT) [4] or even according to the greyscale median of the atheromatic plaque [5]. As a result, plaque classifications, such as that of Geroulakos et al [6], have been developed to provide us with more specific and clinically orientated algorithms that could be used in daily routines. However, there is still a grey area of asymptomatic patients who cannot be adequately graded in terms of their risk, owing to insufficient evidence.

The advances in medical imaging, image analysis and biomechanics provide us with promising new tools in the quest for more sensitive markers of plaque vulnerability. The identification and proper imaging of stress patterns that could trigger the rupture of a carotid plaque leading to thrombus formation and cerebral ischaemia could really be the key problem and ideally could provide us with a reliable method to identify this type of high-risk plaque earlier and more accurately.

Basic principles

Rheological and mechanical properties of the carotid plaque system

Blood is a non-Newtonian fluid whose flow properties are not described by a single constant value of viscosity. It is widely accepted that blood is a shear thinning fluid whose viscosity increases non-linearly with reduction in shear rate. In contrast, blood flow is usually described by Navier–Stokes equations, which describe the motion of fluid substances. These are differential equations that do not explicitly establish a relation among the variables of interest (such as pressure and velocity) but instead establish relations among the rates of changes.

The arterial wall of medium-sized and large arteries has elastic properties that resemble those of an elastic tube. However, factors such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking and ageing cause significant changes to the arterial wall through time [7]. These contribute to the dynamic and changing nature of this tube, which cannot be easily simulated. Young's elastic modulus and the brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) [8] have been used to assess the arterial stiffness.

Finally, the structure of atherosclerotic plaques is variable and may consist of different predominant substances. For example, some plaques are more lipid rich and thus unstable, whereas others are more fibrotic and stable. Different types of plaque are, as expected, associated with different biomechanical behaviour to stress and interact differently to the blood flow and changes in shear stress during the cardiac circle.

Biomechanical parameters of carotid arteries

In the literature, a number of biomechanical parameters have been used to describe the biomechanical behaviour of the carotid arteries. These include (a) the circumferential wall tension (CWT), (b) the tensile stress (TS), (c) the wall shear stress (WSS) and (d) Young's elastic modulus (YEM) [9] (Table 1).

Table 1. Simplified formulas of the various types of stresses encountered during the wall stress analysis.

| Type of stress | Simplified formula | Description of action |

| 1. Circumferential wall tension (CWT) | CWT (dynes cm–2) = SBP× (ID/2) | Adjacent parts of the material tend to press against each other through a typical stress plane |

| 2. Tensile stress (TS) | TS (dynes cm–2) = CWT/IMT | Two sections of material on either side of a stress plane tend to pull apart or elongate |

| 3. Wall shear stress (WSS) | WSS = 8×μ× (MV/ID) | Two parts of a material tend to slide across each other in any typical plane of shear upon application of force parallel to that plane |

| 4. Young's elastic modulus (YEM) | YEM (dynes cm–3) = (SBP – DBP) × (IDM/[(IDT – IDR) ×IMT] | Describes arterial wall stiffness |

| 5. Stress phase angle (SPA) | SPA = CWS/WSS | Combination of CWS and WSS |

SBP, systolic blood pressure; ID, internal diameter in cm; IMT, intima–media thickness; μ, blood viscosity; MV, mean velocity; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; IDM, IDR+ (IDT – IDR)/3; IDR, internal diameter during R wave of cardiac cycle, IDT, internal diameter during T wave of cardiac cycle; CWS, circumferential wall stress/strain.

The complexity of the above-described interactions between rheological and structural factors, like blood, arterial wall and plaque, and biomechanical factors, such as CWT, TS, and WSS, is obvious, and calculations without using oversimplified assumptions demand increased technical knowledge and powerful software. Fluid–structure interactions (FSIs) describe the interactions of a deformable structure with an internal or surrounding fluid flow and can be achieved using the recent advances in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and finite element analysis (FEA) [10].

The purpose of this article is to review the recent developments in this field, focusing on the clinical evidence and emphasising the difficulties in acquiring information about the impact of haemodynamic forces in human carotid plaque composition and vulnerability.

Review criteria

The PubMed and Scopus databases were searched for clinical studies evaluating the effect of various types of biomechanical stress on human carotid plaque vulnerability. The search terms used were “wall stress”, “shear stress”, “tensile stress”, “carotid plaque disease” and “vulnerable plaque” in various combinations. The selected studies were manually searched for relevant publications (published between 1980 and 2009) from their reference lists. All clinical studies that reported results on the effect of any type of stress on human carotid plaque stability were retrieved and included in the final analysis.

Mechanical stress and the association with the carotid plaque pathogenesis

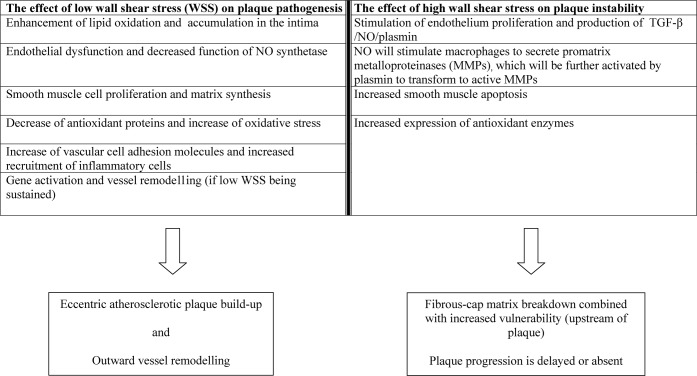

Each section of carotid arteries is not affected to the same extent by atherosclerosis, and investigation of the pathological process has revealed that these lesions are most commonly encountered in areas of low WSS [11]. Areas of bifurcation or curved arteries are portrayed as areas where low or oscillatory WSS occurs [12], and this observation corresponds with the clinical experience of plaque disposition mainly at these sites (Figure 1). The theory behind the mechanisms of plaque creation indicates that it is the oscillatory in combination with the low WSS that is mainly responsible for endothelial dysfunction, whereas the unidirectional shear stress may protect the endothelial layer [13–15].

Figure 1.

Wall shear and the corresponding tensile stress (in N m–2) patterns for a normal carotid bifurcation.

Effect of stress on the arterial endothelium

It is believed that the key factor to plaque pathogenesis is the interaction between low or/and oscillatory WSS and the subjacent endothelium, which responds by upregulation of vaso-occlusive agents and downregulation of vasodilating agents such as endothelial nitric oxide synthetase (eNOS) gene expression [13, 15]. In porcine carotid artery models that were exposed for 3 days to unidirectional high and low WSS or to oscillatory WSS there was an increase in the expression levels of metalloproteinase-2 and -9 and a decrease in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in the latter group [16].

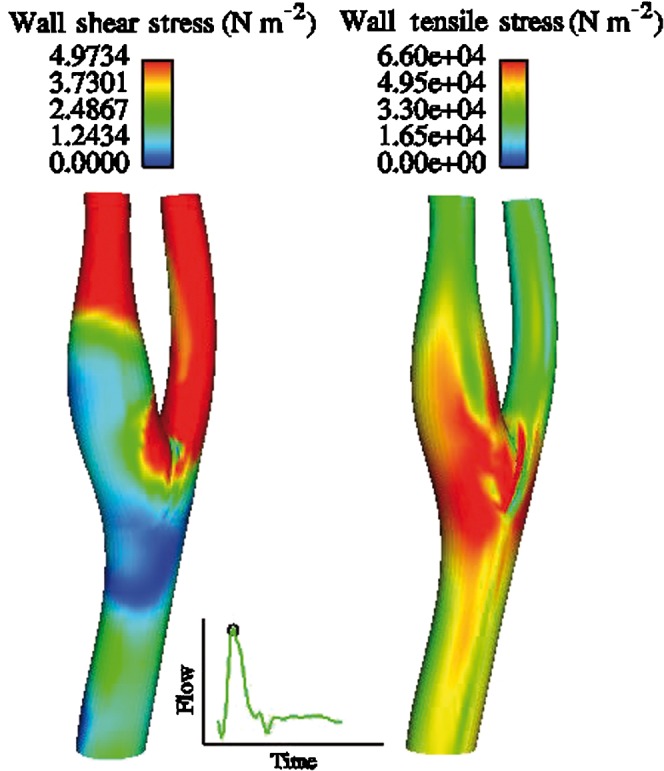

These results indicate that wall remodelling of the artery may be caused by such a plaque-prone haemodynamic setting, and this is also supported by other experimental studies [12]. High WSS is generally considered as an important destabilising factor through the induced changes to the endothelium and smooth muscle cells of the plaque matrix, as summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of the effect of wall shear stress (WSS) on atherosclerotic plaque development and rupture. TGF, transforming growth factor.

Effect of stress on plaque progression and severity

Apart from the effect of WSS on the initial mechanisms of plaque formation, there is clinical evidence suggesting its important role in plaque progression and the observed severity of carotid atherosclerosis. Lee and colleagues [17] evaluated the IMT and plaque burden in bilateral common carotid artery bifurcations, external and internal carotid arteries using duplex ultrasound in 80 untreated hypertensive patients. They presented evidence suggesting that circumferential wall stress (CWS) and TS are related to the severity of carotid plaque disease in this specific patient group.

Additionally, Tang and colleagues [18] combined in vivo MRI-based two-dimensional (2D)/three-dimensional (3D) multicomponent models with fluid–structure interactions to study 21 human carotid plaques. Lower plaque and lower flow WSS were shown to contribute significantly to continued eccentric plaque progression.

Intraluminal stresses are affected by a variety of different factors. The carotid geometry itself was found to have an important effect on blood flow and on the magnitude of WSS [19]. Moreover, in a previous study it was also shown that flow, diameter and blood viscosity have a significant effect on WSS [20]. Finally, factors such as age, blood pressure, body mass index and IMT have been independently associated with changes in wall shear and CWS [21, 22].

The combined effect of low WSS and high TS has also been evaluated by different groups and is believed to pose an important determinant of carotid plaque formation [22]. This combined effect can be expressed using the phase difference between the solid circumferential stress/strain (CS) and the fluid WSS curves or in other words the stress phase angle (SPA) [23]. Negative SPA appears to be indicative of pro-atherogenic gene expression and vascular remodelling, as shown by experimental data in coronary arteries and the aortic bifurcation [23, 24].

Mechanical stress and carotid plaque vulnerability: the clinical evidence

It has been generally accepted that the degree of carotid lumen stenosis is not a sufficient marker for the underlying risk of plaque rupture [25]. Baseline evidence originating from in vitro (animal or artificial models) or even from computational simulation studies suggests that there are certain plaque characteristics that could be incriminated for plaque destabilisation. The geometrical features of a stenotic lumen—such as eccentricity [26, 27] and lumen curvature [26]—the lipid pool size [27] and the fibrous cap thickness [28, 29] have been associated with instability in these experimental settings. Histological data from carotid endarterectomy specimens suggest that a combination of representative cap thickness of less than 500 μm and minimum cap thickness of less than 200 μm can be independently associated with cap rupture, according to the Oxford plaque study [30].

The effect of carotid plaque characteristics on stress distribution in clinical settings

The current clinical evidence (Table 2) is rather limited but corresponds well to the previous experimental evidence. Fibrous cap thickness appears to be strongly associated with the stress levels applied on the plaque and consequently with the risk for rupture and thromboembolic events [31–33]. Lumen curvature was another characteristic associated with instability [32] in clinical settings. In addition, calcium deposition within plaque [34] or ulceration may alter the local stress patterns or become altered by them, respectively, affecting the structural behaviour of the plaque [35].

Table 2. Clinical evidence regarding the relation of arterial wall stresses with plaque morphology and vulnerability.

| Gao and Long [31] | 13 carotid bifurcation cases | Wall TS/Von Mises stress | 3D plaque reconstruction from histology sections | FSI simulation | Stress level on the fibrous cap is much more sensitive to the changes in the fibrous cap thickness than the lipid core volume. |

| Paini et al [41] | Patients with recent ischaemic CVE event and either a plaque on CCA (n = 25) or no plaque (n = 37). | Bending strain | Non-invasive echotracking system | Longitudinal gradients of distensibility and Young's elastic modulus | NIDDM and dyslipidaemia associated with a stiffer carotid at the level of the plaque than in the adjacent common carotid artery leading to an inward-bending stress. Repetitive bending strain may be associated with plaque fatigue and rupture |

| Gillard et al [34] | 3 patients with calcified carotid plaques | Maximum stress | hrMRI | FEA simulation | Calcification at the thin fibrous cap may result in high stress concentrations, increasing the risk of plaque rupture |

| Li et al [32] | 20 symptomatic and 20 asymptomatic patients | Maximum stress | hrMRI | FEA simulation | Large lumen curvature and thin fibrous cap are closely related to plaque vulnerability |

| Beaussier et al [42] | 92 patients with carotid plaques (66 patients with essential HTN and 26 NTN patients) | Bending strain | Non-invasive echotracking system | NR | Arterial wall material of HTN patients less elastic at the site of the plaque and carotid was inwardly strained in the zone affected by plaque. This may generate a high level of stress concentrations and fatigue, exposing the plaque to a greater risk of rupture |

| Kock et al [33] | 2 symptomatic patients | Longitudinal stress | MRI | FSI simulation combined FEA with CFD simulations | Longitudinal fibrous cap stresses may prove useful in assessing plaque vulnerability and improve risk stratification in patients with carotid atherosclerosis |

| Trivedi et al [37] | 5 symptomatic and 5 asymptomatic patients | Principal (shear) stress | MRI | FEA simulation | Significant differences in plaque stress exist between plaques from symptomatic individuals and those from asymptomatic individuals |

| Groen et al [35] | 1 patient with baseline carotid plaque and an ulcer at 10 month f/u | Wall shear stress | Serial MRI | CFD | Plaque ulceration was located at the area of high wall shear stress. This suggests that WSS influence plaque vulnerability |

TS, tensile stress; 3D, three dimensional; FSI, fluid–structure interactions; CVE, cerebrovascular events; CCA, common carotid artery; NIDDM, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; hr, high resolution; FEA, fine element analysis; HTN, hypertension; NTN, non-hypertensive; NR, not reported; CFD, computer fluid dynamics; f/u, follow-up.

The effect of different types of stress on carotid plaque stability

Attempts have been made to evaluate the effect of different types of stress in clinical and experimental settings. The existing clinical evidence suggests that the various types of biomechanical stress (WSS, TS and CWT) may different associations with plaque stability. High WSS especially on the upstream of the plaque is several times lower in magnitude than TS but it is possibly the factor leading to the formation of unstable plaque characteristics [35–38]. High TS [31, 39, 40], induced by blood pressure pulse, is proposed as the most important factor eventually causing plaque rapture; repetitive inward bending [41, 42] of stiff carotid arteries may also be considered among potential contributors to the plaque structural fatigue and thrombogenic complications. However, so far, there is limited or sometimes even conflicting clinical evidence about whether one of these factors plays a more important role or if it is a matter of combined effect.

Limitations of the clinical evidence

Despite the number of experimental and computational studies there are still doubts with regard to the clinical implications of these novel and promising biomechanical characteristics. The present clinical evidence is rather limited and the number of studied patients is insufficient to reach safe conclusions. In addition, there is considerable variation in the type of stresses or wall/plaque characteristics analysed as well as the methods applied for the stress analysis and imaging. In the majority of the studies, MRI has been used combined with FSI simulations, contributing to the increased cost and complexity of the studies. Finally, each study—apparently because of the technical complexity—focused on a different type of stress or arterial wall/plaque characteristic and thus the potential combined effect of various stress types on an anisotropic carotid plaque model has not been adequately explored.

New techniques

The increased cost and technical complexity of 3D MRI reconstruction for the analysis of the wall–stress relation is an important limitation of this approach. Other non-invasive ultrasound-based techniques could be applied, taking into consideration the recent technological progress. Non-invasive vascular elastography, motion plaque analysis and 3D ultrasound imaging are alternative potential approaches.

Non-invasive vascular elastography is a method to evaluate the vulnerability and the composition of a plaque creating elasticity maps, potentially enabling investigators to differentiate lipid pools and fibrotic plaques [43]. Motion analysis of carotid plaques during systole and diastole may also reveal different mechanisms that participate in plaque fatigue and rupture. A computerised method that objectively analyses such motion patterns using ultrasound images has been developed using 2D displacement vector maps. Motion analysis theory advocates that distinguished plaque regions may present different motion patterns [44].

Finally, there is a rising amount of evidence regarding 3D ultrasound imaging and its potential applications in arterial wall and plaque image reconstruction, as well as to the direct evaluation of plaque volume [45]. The potential of combining 3D ultrasound imaging and computational fluid dynamic analysis has not been adequately explored with regard to the clinical effect of stress patterns on plaque vulnerability and poses a significant challenge for future studies. However, there is preliminary evidence that WSS patterns derived from 3D ultrasound imaging can be both well reproducible and potentially comparable, if not superior, than those acquired from MRI [46].

Conclusions

Carotid plaque stress analysis appears as a promising diagnostic approach based on established biomechanical and haemodynamic properties. Prospective, clinical studies are warranted to investigate in depth the applicability of the different aspects of this advance into daily, clinical practice. Established imaging techniques, such as MRI or 2D ultrasound, could be further developed. In addition, novel, ultrasound-based techniques, like elastography, plaque motion analysis and especially 3D ultrasound, could be investigated in order to reduce cost and complexity and increase the quality of information regarding wall stress–carotid plaque interactions. A multidisciplinary approach that includes vascular surgeons, radiologists and bioengineers, is essential to accomplish this challenging task.

References

- 1.Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA 1995;273:1421–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Ferguson GG, Haynes RB, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med 1998;12:339:1415–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Carotid Surgery Trialists Collaborative Group Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet 1998;351:1379–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollander M, Hak AE, Koudstaal PJ, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, Hofman A, et al. Comparison between measures of atherosclerosis and risk of stroke, The Rotterdam Study. Stroke 2003;34:2367–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakkos SK, Stevens JM, Nicolaides AN, Kyriacou E, Pattichis CS, Geroulakos G, et al. Texture analysis of ultrasonic images of symptomatic carotid plaques can identify those plaques associated with ipsilateral embolic brain infarction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007;33:422–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geroulakos G, Ramaswami G, Nicolaides A, James K, Labropoulos N, Belcaro G, et al. Characterization of symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid plaques using high-resolution real-time ultrasonographic. Br J Surg 1993;80:1274–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milio G, Corrado E, Sorrentino D, Muratori I, La Carrubba S, Mazzola G, et al. Asymptomatic carotid lesions and aging: Role of hypertension and other traditional and emerging risk factors. Arch Med Res 2006;37:342–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung CS, Lin JW, Hsu CN, Chen HM, Tsai RY, Chien YF, et al. Using brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity to associate arterial stiffness with cardiovascular risks. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2009;19:241–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carallo C, Irace C, Pujia A, De Franceschi MS, Crescenzo A, Motti C, et al. Evaluation of common carotid hemodynamic forces. Relations with wall thickening. Hypertension 1999;34:217–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birchall D, Zaman A, Hacker J, Davies G, Mendelow D. Analysis of haemodynamic disturbance in the atherosclerotic carotid artery using computational fluid dynamics. Eur Radiol 2006;16:1074–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnasso A, Irace C, Carallo C, De Franceschi MS, Motti C, Mattioli PL, et al. In vivo association between low wall shear stress and plaque in subjects with asymmetrical carotid atherosclerosis. Stroke 1997;28:993–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, van derBaan A, Grosveld F, Daemen MJ, et al. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation 2006;113:2744–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gambillara V, Chambaz C, Montorzi G, Roy S, Stergiopulos N, Silacci P. Plaque-prone hemodynamics impair endothelial function in pig carotid arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;290:H2320–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melchionna R, Porcelli D, Mangoni A, Carlini D, Liuzzo G, Spinetti G, et al. Laminar shear stress inhibits CXCR4 expression on endothelial cells: functional consequences for atherogenesis. FASEB J 2005;19:629–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slager CJ, Wentzel JJ, Gijsen FJ, Schuurbiers JC, van derWal AC, van derSteen AF, et al. The role of shear stress in the generation of rupture-prone vulnerable plaques. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2005;2:401–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gambillara V, Montorzi G, Haziza-Pigeon C, Stergiopulos N, Silacci P. Arterial wall response to ex vivo exposure to oscillatory shear stress. J Vasc Res 2005;42:535–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee MY, Wu CM, Yu KH, Chu CS, Lee KT, Sheu SH, et al. Association between hemodynamics in the common carotid artery and severity of carotid atherosclerosis in patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2008;21:765–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang D, Yang C, Mondal S, Liu F, Canton G, Hatsukami TS, et al. A negative correlation between human carotid atherosclerotic plaque progression and plaque wall stress: in vivo MRI-based 2D/3D FSI models. J Biomech 2008;41:727–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen KT, Clark CD, Chancellor TJ, Papavassiliou DV. Carotid geometry effects on blood flow and on risk for vascular disease. J Biomech 2008;41:11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Box FM, van derGeest RJ, Rutten MC, Reiber JH. The influence of flow, vessel diameter, and non-newtonian blood viscosity on the wall shear stress in a carotid bifurcation model for unsteady flow. Invest Radiol 2005;40:277–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson SK. Carotid artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. N Engl J Med 1999;340:14–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao SZ, Ariff B, Long Q, Hughes AD, Thom SA, Stanton AV, et al. Inter-individual variations in wall shear stress and mechanical stress distributions at the carotid artery bifurcation of healthy humans. J Biomech 2002;35:1367–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tada S, Tarbell JM. A computational study of flow in a compliant carotid bifurcation-stress phase angle correlation with shear stress. Ann Biomed Eng 2005;33:1202–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiu Y, Tarbell JM. Interaction between wall shear stress and circumferential strain affects endothelial cell biochemical production. J Vasc Res 2000;37:147–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnsen SH, Mathiesen EB. Carotid plaque compared with intima-media thickness as a predictor of coronary and cerebrovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2009;11:21–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinman DA, Poepping TL, Tambasco M, Rankin RN, Holdsworth DW. Flow patterns at the stenosed carotid bifurcation: effect of concentric versus eccentric stenosis. Ann Biomed Eng 2000;28:415–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang D, Yang C, Kobayashi S, Ku DN. Effect of a lipid pool on stress/strain distributions in stenotic arteries: 3-D fluid-structure interactions (FSI) models. J Biomech Eng 2004;126:363–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li ZY, Howarth S, Trivedi RA, U-King-Im JM, Graves MJ, Brown A, et al. Stress analysis of carotid plaque rupture based on in vivo high resolution MRI. J Biomech 2006;39:2611–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li ZY, Howarth SP, Tang T, Gillard JH. How critical is fibrous cap thickness to carotid plaque stability? A flow-plaque interaction model. Stroke 2006;37:1195–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Redgrave JN, Lovett JK, Gallagher PJ, Rothwell PM. Histological assessment of 526 symptomatic carotid plaques in relation to the nature and timing of ischemic symptoms: the Oxford plaque study. Circulation 2006;113:2320–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao H, Long Q. Effects of varied lipid core volume and fibrous cap thickness on stress distribution in carotid arterial plaques. J Biomech 2008;41:3053–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li ZY, Tang T, U-King-Im J, Graves M, Sutcliffe M, Gillard JH. Assessment of carotid plaque vulnerability using structural and geometrical determinants. Circ J 2008;72:1092–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kock SA, Nygaard JV, Eldrup N, Fründ ET, Klaerke A, Paaske WP, et al. Mechanical stresses in carotid plaques using MRI-based fluid-structure interaction models. J Biomech 2008;41:1651–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li ZY, Howarth S, Tang T, Graves M, U-King-Im J, Gillard JH. Does calcium deposition play a role in the stability of atheroma? Location may be the key. Cerebrovasc Dis 2007;24:452–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groen HC, Gijsen FJ, van derLugt A, Ferguson MS, Hatsukami TS, van derSteen AF, et al. Plaque rupture in the carotid artery is localized at the high shear stress region: a case report. Stroke 2007;38:2379–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groen HC, Gijsen FJ, van derLugt A, Ferguson MS, Hatsukami TS, et al. High shear stress influences plaque vulnerability. Stroke 2007382379–81 Neth Heart J 2008;16:280–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trivedi RA, Li ZY, U-King-Im J, Graves MJ, Kirkpatrick PJ, Gillard JH. Identifying vulnerable carotid plaques in vivo using high resolution magnetic resonance imaging-based finite element analysis. J Neurosurg 2007;107:536–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slager CJ, Wentzel JJ, Gijsen FJ, Thury A, van derWal AC, Schaar JA, et al. The role of shear stress in the destabilization of vulnerable plaques and related therapeutic implications. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2005;2:456–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang D, Yang C, Kobayashi S, Zheng J, Vito RP. Effect of stenosis asymmetry on blood flow and artery compression: a three-dimensional fluid-structure interaction model. Ann Biomed Eng 2003;31:1182–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang D, Yang C, Kobayashi S, Ku DN. Steady flow and wall compression in stenotic arteries: a three-dimensional thick-wall model with fluid-wall interactions. J Biomech Eng 2001;123:548–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paini A, Boutouyrie P, Calvet D, Zidi M, Agabiti-Rosei E, Laurent S. Multiaxial mechanical characteristics of carotid plaque: analysis by multiarray echotracking system. Stroke 2007;38:117–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beaussier H, Masson I, Collin C, Bozec E, Laloux B, Calvet D, et al. Carotid plaque, arterial stiffness gradient, and remodeling in hypertension. Hypertension 2008;52:729–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maurice RL, Ohayon J, Frétigny Y, Bertrand M, Soulez G, Cloutier G. Noninvasive vascular elastography: theoretical framework. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2004;23:164–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bang J, Dahl T, Bruinsma A, Kaspersen JH, Nagelhus Hernes TA, et al. A new method for analysis of motion of carotid plaques from RF ultrasound images. Ultrasound Med Biol 2003;29:967–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ainsworth CD, Blake CC, Tamayo A, Beletsky V, Fenster A, Spence JD. 3D ultrasound measurement of change in carotid plaque volume: a tool for rapid evaluation of new therapies. Stroke 2005;36:1904–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Augst AD, Barratt DC, Hughes AD, Glor FP, McG Thom SA, Xu XY. Accuracy and reproducibility of CFD predicted wall shear stress using 3D ultrasound images. J Biomech Eng 2003;125:218–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]