Abstract

A randomized controlled trial of screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) among at-risk (based on average number of drinks per week, and drinks per drinking day) and dependent drinkers was conducted in an emergency department (ED) among 446 patients 18 and older in Sosnowiec, Poland. Patients were recruited over a 23-week period (4:00 pm to 12:00 midnight) and randomized to one of three conditions: screened-only (n=147), assessed (n=152), and intervention (n=147). Patients in the assessed and intervention conditions were blindly reassessed via a telephone interview at 3 months, and all three groups assessed at 12 months (screened only = 92, assessed = 99, intervention = 87). No difference was found across the three conditions in at-risk drinking at 12 months, as the primary outcome variable, or in decrease in the number of drinks per drinking day, with all three groups showing a significant reduction in both. Significant declines between baseline and 12 months in secondary outcomes of the RAPS4, number of drinking days per week and the maximum number of drinks on an occasion were seen only for the intervention condition, and in negative consequences for both the assessment and intervention conditions. Data suggest that improvements in drinking outcomes found in the assessment condition were not due to assessment reactivity, with both the screened and intervention conditions demonstrating greater (although non-significant) improvement than the assessed condition. Although group by time interaction effects were not found to be significant, findings show that declines in drinking measures for those receiving a brief intervention can be maintained at long-term follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Studies of brief intervention in the emergency department (ED) are relatively few compared to studies in primary care settings, and have reported mixed results regarding the efficacy of a brief intervention in this setting (Dinh-Zaar, et al., 2004; Havard, et al., 2008; Nilsen, et al., 2008). Key issues that may have influence these varied findings include the severity of drinking and assessment reactivity, among others (Bernstein and Bernstein, 2008). For example, the recent D’Onofrio et al. study (2008), which showed no intervention effect, recruited patients at the lower end of the drinking spectrum: 64% had AUDIT scores below the usual cutoff of 8 and mean baseline consumption was below the NIAAA low-risk guidelines of 14 drinks per week. Research has suggested that brief intervention directed toward those in the mild range of drinking severity compared to those in the moderate to heavier range is more likely to show no difference in drinking outcomes (Bernstein and Bernstein, 2008). The lack of a true (unassessed) control group has also been an issue; Daeppen et al. (2007) reported inclusion of an unassessed control group to evaluate assessment reactivity and found no difference in outcomes from the intervention group.

To further address issues related to severity of drinking and assessment reactivity, a brief intervention study was conducted in an emergency department (ED) in Poland, a Central European spirits drinking country (now alongside beer), characterized by infrequent, but heavy drinking, with high levels of intoxication, especially among males (Moskalewicz, 1993). A prior study in this same ED, located in the more traditional Southern region of the country where the typical Polish heavy drinking pattern is especially prominent, found 25% consumed more than 12 liters of alcohol annually and 16% met diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder (Cherpitel, et al., 2005; Moskalewicz, et al., 2006)].

Reported here are 12-month outcomes of this brief intervention study, where baseline drinking is well above NIAAA safe drinking guidelines (no more than 14 standard drinks per week for males and 7 for females, or no more than 4 drinks per day for males and 3 for females), and where a screened-only condition was not assessed at the three-month follow-up. The screened-only condition is compared to the assessed and intervention conditions on at-risk drinking, as the main outcome, and on the number of drinking days per week, the number of drinks per drinking day, the maximum number of drinks on as occasion and negative consequences of drinking. Three-month follow-up of this study found no intervention effect in drinking outcomes between the assessed and intervention condition (Cherpitel, et al., in press-b).We hypothesized that, compared to the screened-only condition, standard care with assessment and the motivational interview would lead to significantly greater reductions in at-risk drinking, and the motivational interview would lead to significantly great reductions in at-risk drinking than the assessment condition. Given the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma mandate for screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in all level-one trauma centers in the U.S. (Committee on Trauma, 2006), findings reported here are especially important regarding the efficacy of brief intervention among those drinking well above the NIAAA safe drinking guidelines and further evaluation of assessment reactivity among heavy drinkers in this setting.

METHODS

Screening

With Polish institutional IRB approval, patients 18 years and older attending the ED in Sosnowiec, Poland between 4:00 pm and 12:00 midnight seven days a week over a 23-week period (May November 2007) were screened with the Rapid Alcohol Problems Screen (RAPS4) (Cherpitel, 2000; Cherpitel, et al., 2005) as a measure of alcohol dependence for both the last year and last three months, and three questions ascertaining at-risk drinking as measured by the number of drinking days per week and the number of drinks per average drinking day during the last year, and the maximum number of drinks on an occasion during the last month. The RAPS4 is a four-item instrument, which was developed in an ED setting based on an optimal set of screening items from several instruments, and with a cut point of one has been found to perform better than other instruments (Cherpitel, 2000). It has previously been validated in this Polish ED population with a sensitivity of .96 and specificity of .89 for alcohol dependence (Cherpitel, et al., 2005). Patients screened eligible for the study if positive on any one of the four RAPS4 items during the last year, or reported 11 or more U.S. standard drinks per week for males (6 or more for females), or reported 4 or more drinks on a typical drinking day for males (3 or more for females) in the last year, applying a somewhat lower threshold for screening criteria than the NIAAA guidelines of 15 or more standard drinks per week for males (8 or more for females) or 5 or more standard drinks in any day during the last year for males (4 or more for females). A lower threshold was applied for screening criteria as the NIAAA guidelines are based, in part, on the maximum number of drinks in any one day within the last year, while in the Polish study screening criteria were based, also in part, on the number of drinks in a typical drinking day in the last year, to better reflect the Polish drinking pattern of infrequent but heavy drinking. A patient reporting a given average number of drinks per drinking day would likely exceed that amount on at least one day in the last year.

Recruitment, Randomization and Attrition

Patient screening reached 65% (n=1913) of the target population (those admitted to the ED between 4 pm and midnight). Reasons for failure to screen included refusals (due primarily to lack of time), severity of health condition (as determined by medical staff), inability to locate the patient, high level of intoxication as deemed by medical staff, and for a variety of other reasons which primarily included being missed because of the heavy flow of patients through the ED and the chaotic circumstances surrounding the ED visit. Of those screened, 26% (n=494) screened eligible for the study and of those eligible, 90% (n=446) were recruited into the study. After agreeing to participate and providing a signed informed consent, patients were then randomized using a two-stage process, whereby they were first randomized to either the screen-only or assessment condition by the study interviewer (generally college students or new graduates) who drew an envelope with the condition assignment. The envelope of those receiving an assessment contained a second envelope, which was opened by the interviewer following assessment to determine whether or not the patient was assigned to the intervention condition. All patients provided contact information for at least two individuals who would always know their whereabouts. This randomization procedure resulted in 147 in the screened condition, 152 in the assessed condition and 147 in the intervention condition. Of the 147 patients randomized to the intervention condition, two refused the intervention but are analyzed in the intervention condition as intention to treat. A list of AA groups and specialized services for alcohol treatment and counseling was provided to the patients in all three conditions.

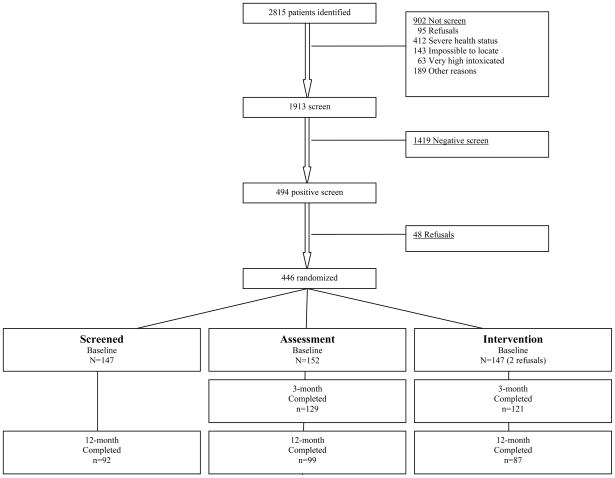

Screened patients were re-contacted at three months to verify contact information, while assessment and intervention patients were both reassessed at three-month follow-up. All three groups were assessed at 12-month follow-up. Figure 1 shows the flow chart for patient screening, recruitment and follow-up. Follow-up rates at 12 months for those followed-up at 3 months were 63% for the screened condition (n=92), 65% for the assessment condition (n=99) and 59% for the intervention condition (n=87). Reasons for non-follow-ups were not significant across the three conditions, with 24% due to refusals, 56% to failure to locate the patient and the remainder to 9 patients who had died, 15 who had moved away, 2 in prison and 2 in the hospital (not shown).

Figure 1.

Assessment and Intervention

Patient randomized to the assessment and intervention conditions were breathalyzed using the Alco-Sensor III (Gibb, et al., 1984) as an estimate of blood alcohol concentration, and asked a number of questions regarding self-reported drinking within six hours prior to the event bringing the patient to the ED, feeling drunk at the time of the event, causal attribution of the event to drinking, quantity and frequency of usual drinking using the Timeline Followback for the last 30 days (Sobell and Sobell, 1992), negative consequences of drinking using the Short Inventory of Problems (SIPs + 6) (Miller, et al., 1995) over the last 12 and 3 months, readiness and stage of change using the Readiness Ruler (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1992; Rollnick, et al., 1992), and risk taking, impulsivity and sensation seeking dispositions using the Abbreviated Risk Taking/Impulsivity and Sensation Seeking Scales (Cherpitel, 1993). All instruments had previously undergone translation in Polish, verified by either back-translation according to Beslin (1986) or attestation by an expert experienced in cross-cultural investigations from the Polish Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology (IPN), and used in other clinical populations in Poland. A cadre of interviewers were trained by the authors and supervised by survey research staff from IPN to carry out screening, recruitment, randomization and assessment procedures (Cherpitel, et al., in press-a).

Patients randomized to the intervention condition received a brief motivational intervention while waiting for treatment, by a nurse who had been trained in SBIRT see Cherpitel (in press-a) (Cherpitel, et al., in press-b), using Brief Negotiation Interviewing (BNI) (Bernstein, et al., 1997), which takes about 15–20 minutes to complete, and integrates the elements of motivational interviewing and readiness to change (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1992) with specific action.

12-Month Follow-up Assessment

Patients in all three conditions were assessed at 12-month follow-up by an interviewer blinded to group status by telephone, regarding the RAPS4, at-risk drinking, the Timeline Followback (30 days), SIPS +6 (3 months) and Readiness and Stage of Change. Patients were also asked whether they obtained treatment for their drinking during the last 3 months. Those not reachable by phone were contacted in person (n=34; 12%). Baseline demographic and drinking characteristics were compared between those followed-up at 12-months and those not reached (not shown). No statistically significant differences were found for the intervention condition, while for the screened condition those lost to follow-up were more likely than those successfully followed to be positive on the RAPS4 for the last 3 months (p<0.05) and to report a greater number of drinks on an occasion (p<0.01), and those lost to follow-up in the assessment condition were more likely to be injured and to also to report a greater number of drinks on an occasion (p<0.05).

Data Analysis

Demographic and drinking characteristics were compared across the three conditions at baseline, using independent tests of difference in proportions for dichotomous measures and independent t-tests for continuous measures.

Because of the significant differences in drinking characteristics across the three conditions at baseline, and because the literature suggests that brief intervention is most efficacious for those drinking at a non-dependent level (Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative, 2007), subsequent analyses were restricted to those who reported an average of not more than six drinks per day at baseline. Five patients in the screened condition, 2 in the assessed condition and 7 in the intervention condition did not meet this criterion, and were excluded from the 12-month follow-up analysis.

Drinking outcomes were then compared between baseline assessment and 12-month follow-up, separately, for those in each of the three conditions who did not exceed the 6 drinks per day maximum, using McNemar’s chi-squared test for dichotomous measures and paired t-tests for continuous measures. Multivariate group by time interactions were also carried out in random intercept models controlling for gender and age and including the effect of time as two indicator variables, one for the 3 and the other for the 12 month follow-up, with the intercept accounting for the estimated baseline value. Such a model allows for a test of a differential effect of group across time while not forcing the assumption that the outcome changes linearly with time.

RESULTS

As seen in Table 1, despite randomization, significant differences were found across the three conditions for the number of drinking days per week and negative consequences of drinking.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for total sample by treatment condition

| Screened (n=147) | Assessment (n=152) | Intervention (n=147) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injured (%) | n/a | 77.0 | 63.9^ |

| Male (%) | 83.0 | 85.5 | 85.0 |

| Age <30 (%) | 34.7 | 43.4 | 45.6 |

| 1+ RAPS4 (%)(last 3 months) | 35.4 | 38.8 | 42.9 |

| At-risk drinking (%) | 83.0 | 89.5 | 88.4 |

| Drinking pattern | |||

| # drinking days per week (mean, se) | 2.5 ( 0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | 3.0 ^(0.2) |

| # drinks per drinking day (mean, se) | 5.5 ( 0.4) | 5.6 (0.4) | 7.0 (0.8) |

| # maximum drinks on an occasion last month (mean, se) | 8.9 (0.7) | 9.2 (0.6) | 10.7 (0.8) |

| Negative consequences (#)(mean, se, last 3 months) | n/a | 1.8 (0.3) | 2.7^ (0.3) |

| Alcohol Treatment 12 months prior (n) | (4) | (2) | (1) |

p<0.05, test of difference between screen, assessment and intervention groups

Note: Independent test of difference in proportion on dichotomous measures and independent ANOVA on continuous measures

Table 2 shows the baseline and 12-month values across the three conditions, for those followed-up at 12 months who met the baseline six-drink criterion. Despite the six-drink criterion, those in the intervention condition were significantly more likely at baseline to report a greater maximum number of drinks per occasion. No difference was found at 12 months in at-risk drinking as the primary outcome variable across the three conditions, with all three groups showing a significant reduction. All three conditions also showed a significant decrease in the secondary outcome of number of drinks per drinking day. Significant declines in secondary outcomes of the RAPS4, number of drinking days per week and the maximum number of drinks on an occasion were seen only for the intervention condition, and in negative consequences for both the assessment and intervention conditions (negative consequences were not obtained at baseline for the screened condition). No significant differences were found for any of these secondary outcome variables across the three conditions at 12-month follow-up and group by time interactions were not significant.

Table 2.

Baseline and 12-month characteristics for those completing all interviews and averaging not more than 6 drinks per day at baseline QF

| Baseline | 12-month follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened (n=87) | Assessment (n=97) | Intervention (n=80) | Screened (n=87) | Assessment (n=97) | Intervention (n=80) | |

| Injured (%) | n/a | 71.1 | 63.8 | -- | -- | -- |

| Male (%) | 82.8 | 85.6 | 85.0 | -- | -- | -- |

| Age <30 (%) | 33.3 | 43.3 | 48.8 | -- | -- | -- |

| At-risk drinking (%) | 87.4 | 88.7 | 87.5 | 54.0*** | 64.9*** | 63.8** |

| 1+ RAPS4 (%)(last 3 months) | 25.3 | 35.1 | 42.5a | 20.7 | 23.7 | 23.8* |

| Drinking patterns | ||||||

| # drinking days per week (mean, se) | 2.3 ( 0.2) | 2.3 ( 0.2) | 2.5 ( 0.2) | 2.0 ( 0.2) | 2.1 ( 0.2) | 1.8 ( 0.2)** |

| # drinks per drinking day (mean, se) | 5.0 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.4) | 3.5** (0.3) | 4.2** (0.4) | 4.1** (0.4) |

| # maximum drinks per occasion last month (mean, se) | 6.7 (0.5) | 7.8 (0.5) | 9.3^ (0.8) | 6.1 (0.6) | 7.7 (0.6) | 7.4 * (0.6) |

| # Negative Consequences last 3 months (mean, se) | n/a | 1.5 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.8 **(0.2) | 0.6 ***(0.2) |

| Alcohol Treatment 12 months prior (n) | ( 2 ) | ( 1 ) | ( 0 ) | ( 2 ) | ( 1 ) | ( 2 ) |

p<0.05 between group comparisons for screen, assessment and intervention conditions at baseline and 12-month follow-up p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001 McNemar Chi2 test is used for dichotomous measures and paired t-test for continuous measures for screened, assessment and intervention, separately

p=.06; pairwise comparisons were not used to avoid Type I error.

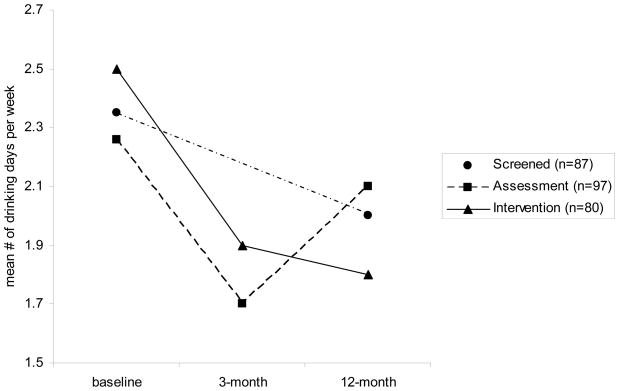

Figures 2–7 show plots, for those averaging not more than six drinks per day, of baseline, three-month and 12-month outcomes for the assessed and intervention conditions completing both follow-ups, and baseline and 12-month outcomes for the screened condition, for at-risk drinking, the RAPS4, drinking days per week, drinks per drinking day, maximum drinks on an occasion, and negative consequences of drinking. All outcome measures in Figures 2–7 declined from the baseline assessment to the 3-month follow-up for the assessed and intervention conditions, but declines from the 3-month assessment to 12-month assessment were only evident for the intervention condition on the RAPS4, number of drinking days per week, the number of drinks per occasion, and negative consequences; only the maximum number of drinks on an occasion increased from the 3-month to 12-month interview for the intervention condition. All outcome measures increased from the 3-month to 12-month interview for the assessed condition. Because information on the number of negative consequences and 3-month drinking information were not collected for the screened condition, only the baseline and 12-month outcomes are depicted in Figures 2–6. This control condition showed significant declines in the mean number of drinks per drinking day (Table 2) and non-significant declines in at-risk drinking, RAPS4, mean number of drinking days per week and the maximum number of drinks per occasion.

Figure 2.

Figure 7.

Figure 6.

DISCUSSION

Of those screened in the Polish ED population, 26% met criteria for at-risk drinking, which was similar to the proportion screening positive in other brief intervention studies (Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative, 2007; Daeppen et al., 2007; Longabaugh et al., 2001). While data on at-risk drinking is not available from the earlier study in this same ED, 17% were found positive on the RAPS4 alone (Cherpitel, et al., 2005). The relatively high rate of at risk drinking in the present study may be attributed, in part, to patient recruitment occurring between 4:00 p.m. and 12:00 midnight, when one might expect a larger proportion of those attending the ED to be alcohol involved than those admitted at other times.

While no difference was found at 12-month follow-up in either primary or secondary outcome variables across the three conditions, with all three conditions showing a significant reduction in at-risk drinking and in the number of drinks per drinking day from baseline, only those in the intervention condition showed significant improvements in all outcome variables at 12-month follow-up. Unlike those studies which have found positive results for brief intervention in the short-term deteriorating on longer-term follow-up (Nilsen, et al., 2008), we see anticipated declines between the baseline and 3-month assessment and, additionally, further declines between the 3- and 12-month assessments for five of the six drinking outcome measures (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7). The assessed condition showed improvement for all drinking measures between baseline and 3-month follow-up, yet did not decrease on any measure between the 3-month and 12-month interviews, with the maximum number of drinks per occasion and number of drinking days per week reaching baseline levels of use. The screened condition decreased on all drinking measures and significantly decreased on at risk drinking and the number of drinks per drinking day, although, without 3-month follow-up data, some caution in interpretation should be used. With a lack of between group differences and non-significant group by time interactions, these data should not be over-interpreted, but merely as suggestive of further research.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Although not significant, declines were seen in the number of drinking days per week and the maximum number of drinks on an occasion for the screened condition (as contrasted to the assessed condition), suggesting improvements in drinking outcomes noted in the assessment condition at 3-month follow-up were not due to assessment reactivity and were not sustained at 12 months. These findings are similar to those from the Daeppen et al. study (2007), where no difference was found between the intervention condition and an unassessed control condition at 12-month follow-up. While screening based on the RAPS4 and NIAAA safe-drinking guidelines may be considered a mild assessment (screened patients were also contacted at 3-months just to verify contact information), the actual assessment applied in this study (both at baseline and 3-month follow-up) was considerably more extensive, and these data suggest that the impact of an elaborated assessment, itself, is not as strong as the impact of the intervention, which has been suggested as an explanation for improved outcomes reported for the assessment condition in prior studies.

One key issue that has influenced findings from previous studies, and may have contributed to positive intervention findings in this study, is the severity of drinking of those recruited into the study (Bernstein and Bernstein, 2008). Brief intervention directed toward those in the mild range of drinking severity compared to those in the moderate range is more likely to show no difference in drinking outcomes (Bernstein and Bernstein, 2008). Although patients in this study reported a relatively small number of drinking days per week (Table 1), they reported a relatively large number of drinks per drinking day and maximum drinks per occasion, reflecting the typical Polish drinking style of infrequent but heavy drinking. Because of this, coupled with the significant differences across the three conditions in baseline drinking characteristics, analysis was restricted to those who reported no more than six drinks per day at baseline, which presumably eliminated the more severely dependent drinkers who may be most likely to accept a referral to outside treatment. Indeed, at 12-month follow-up, only two patients each in the screened condition and intervention conditions and one in the assessment conditions reported alcohol treatment in the prior 12 months, although a list of AA groups and specialized services for alcohol treatment and counseling was provided to all patients at the time of recruitment into the study.

Other issues potentially effecting findings reported here and elsewhere include integrity of the intervention and follow-up rates. The interviewer conducted a brief exit interview with patients receiving the intervention, regarding whether a nurse had talked with them about their drinking and whether the patient was satisfied with the intervention. In all cases patients confirmed that the nurse had talked with them about their drinking and most (98%) were somewhat or very satisfied with the encounter.

Attrition at follow-up my also introduce bias into study findings. While 3-month follow-up rates were high in this study (85% for the assessment condition and 83% for the intervention condition) (Cherpitel, et al., in press-b), substantial losses were sustained at 12-month follow-up, with 63% of the screened condition, 65% of the assessed condition and 59% of the intervention successfully interviewed among those receiving the 3-month follow-up. Although 12-month follow-up rates were not significantly different across the three conditions, those lost to follow-up in both the screened and assessment condition were more likely to report a greater number of drinks on an occasion, compared to those successfully followed. Also of importance is the substantially reduced number of patients across the three conditions at 12-month follow-up, which may have rendered differences between the intervention and assessed condition non-significant.

Study limitations include the fact that no data were available to compare those screened with those not screened, so we do not know how representative those screened were of the study population. Additionally, this study population typified the characteristic infrequent but heavy drinking patterns found in spirits drinking countries of Central Europe, as noted earlier, and findings here may not be generalizable to other cultures with different drinking patterns.

Nevertheless, these findings suggest that improved outcomes found in this and other studies of patients assigned to the assessment condition are not due to assessment reactivity. While the efficacy of brief intervention in the ED has not been as consistently positive as that found in primary care settings (Bernstein and Bernstein, 2008), these data suggest a brief motivational interview applied in the ED is associated with improved drinking outcomes one year later, with only those in the intervention group reporting significant improvement in all outcome variables from baseline to 12-month follow-up. Although group by time interaction effects were not found to be significant, findings show that declines in drinking measures for those receiving a brief intervention can be maintained at long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgments

Support by a grant from the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R21 AA016081-01)

Contributor Information

Cheryl J. Cherpitel, Email: ccherpitel@arg.org, Alcohol Research Group, 6475 Christie Avenue, Suite 400, Emeryville, CA, USA, 510 597-3453, Fax: 510 985-6459.

Rachael A. Korcha, Alcohol Research Group, 6475 Christie Avenue, Suite 400, Emeryville, CA, USA, 510 597-3453, Fax: 510 985-6459.

Jacek Moskalewicz, Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Sobieskiego 9, 02-957 Warsaw, POLAND

Grazyna Swiatkiewicz, Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Sobieskiego 9, 02-957 Warsaw, POLAND

Yu Ye, Alcohol Research Group, 6475 Christie Avenue, Suite 400, Emeryville, CA, USA.

Jason Bond, Alcohol Research Group, 6475 Christie Avenue, Suite 400, Emeryville, CA, USA.

References

- Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative. The impact of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment on Emergency Department patients' alcohol use. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Bernstein J. Effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief motivational intervention in the emergency department setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:751–754. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Levenson S. Project ASSERT: an ED-based intervention to increase access to primary care, preventive services, and the substance abuse treatment system. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner WJ, Berry JW, editors. Field methods in cross-cultural research. Vol. 8. SAGE Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1986. pp. 137–165. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. Alcohol, injury and risk taking behavior: data from a national sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:762–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. A brief screening instrument for problem drinking in the emergency room: the RAPS4. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:447–449. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G. Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in a Polish emergency room: challenges in a cultural translation of SBIRT. J Addict Nurs. doi: 10.1080/10884600903047618. (in press-a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Ye Y, Bond J. Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in a Polish emergency department: three-month outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.982. (in press-b) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G. Screening for alcohol problems in two emergency service samples in Poland: comparison of the RAPS4, CAGE, and AUDIT. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Trauma ACoS. Resources for Optimal Care of Injured Patient. American College of Surgeons; Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Daeppen J-B, Gaume J, Bady P, Yersin B, Calmes J-M, Givel J-C, Gmel G. Brief alcohol intervention and alcohol assessment do not influence alcohol use in injured patients treated in the emergency department: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Addiction. 2007;102:1224–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh-Zaar T, Goss C, Heitman E, Roberts I, DiGuiseppi C. Interventions for preventing injuries in problem drinkers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD001857. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001857.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Onofrio GD, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, Fiellin DA, Busch SH, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, O'Connor PG. Brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:742–750. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb K, Yee A, Johnson C, Martin S, Nowak R. Accuracy and usefulness of a breath alcohol analyzer. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:516–520. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80517-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havard A, Shakeshaft AP, Sanson-Fisher RW. Systematic review and meta-analyses of strategies targeting alcohol problems in emergency departments: interventions reduce alcohol-related injuries. Addiction. 2008;103:368–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Woolard RF, Nirenberg TD, Minugh AP, Becker B, Clifford PR, Carty K, Sparadeo F, Gogineni A. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:806–816. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse [NIH Pub. No. 95-3911] National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health; Rockville, MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Moskalewicz J. Privatization of the alcohol arena in Poland. Contemp Drug Prob. 1993;20:263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y. Results of two emergency room studies. Eur Addiction Res. 2006;12:169–175. doi: 10.1159/000094418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P, Baird J, Mello MJ, Nirenberg TD, Woolard RF, Bendtsen P, Longabaugh R. A systematic review of emergency care brief alcohol interventions for injury patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:184–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Prog Behav Modif. 1992;28:184–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Health N, Bell A. Negotiating behavior change in medical settings: the development of brief motivational interviewing. J Mental Health. 1992;1:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]