Abstract

Background

Treatment of cancer is increasingly effective but associated with short and long term side effects. Oral side effects, including oral mucositis (mouth ulceration), remain a major source of illness despite the use of a variety of agents to treat them.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions for treating oral mucositis or its associated pain in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both.

Search methods

Electronic searches of Cochrane Oral Health Group and PaPaS Trials Registers (to 1 June 2010), CENTRAL via The Cochrane Library (to Issue 2, 2010), MEDLINE via OVID (1950 to 1 June 2010), EMBASE via OVID (1980 to 1 June 2010), CINAHL via EBSCO (1980 to 1 June 2010), CANCERLIT via PubMed (1950 to 1 June 2010), OpenSIGLE (1980 to 1 June 2010) and LILACS via the Virtual Health Library (1980 to 1 June 2010) were undertaken. Reference lists from relevant articles were searched and the authors of eligible trials were contacted to identify trials and obtain additional information.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials comparing agents prescribed to treat oral mucositis in people receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both. Outcomes were oral mucositis, time to heal mucositis, oral pain, duration of pain control, dysphagia, systemic infection, amount of analgesia, length of hospitalisation, cost and quality of life.

Data collection and analysis

Data were independently extracted, in duplicate, by two review authors. Authors were contacted for details of randomisation, blindness and withdrawals. Risk of bias assessment was carried out on six domains. The Cochrane Collaboration statistical guidelines were followed and risk ratio (RR) values calculated using fixed‐effect models (less than 3 trials in each meta‐analysis).

Main results

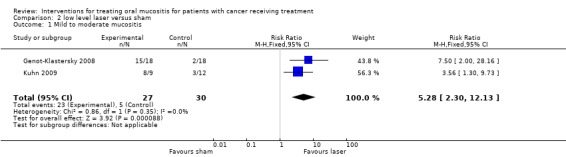

Thirty‐two trials involving 1505 patients satisfied the inclusion criteria. Three comparisons for mucositis treatment including two or more trials were: benzydamine HCl versus placebo, sucralfate versus placebo and low level laser versus sham procedure. Only the low level laser showed a reduction in severe mucositis when compared with the sham procedure, RR 5.28 (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.30 to 12.13).

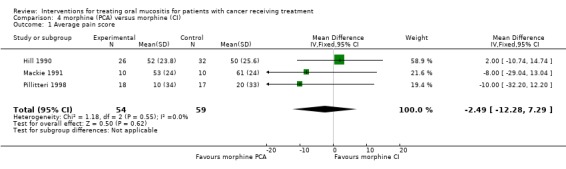

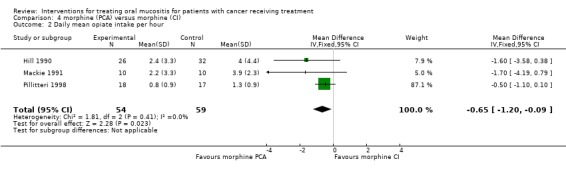

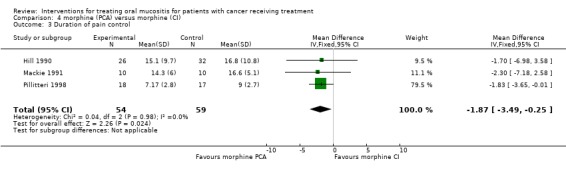

Only 3 comparisons included more than one trial for pain control: patient controlled analgesia (PCA) compared to the continuous infusion method, therapist versus control, cognitive behaviour therapy versus control. There was no evidence of a difference in mean pain score between PCA and continuous infusion, however, less opiate was used per hour for PCA, mean difference 0.65 mg/hour (95% CI 0.09 to 1.20), and the duration of pain was less 1.9 days (95% CI 0.3 to 3.5).

Authors' conclusions

There is limited evidence from two small trials that low level laser treatment reduces the severity of the mucositis. Less opiate is used for PCA versus continuous infusion. Further, well designed, placebo or no treatment controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of interventions investigated in this review and new interventions for treating mucositis are needed.

Keywords: Humans, Analgesics, Analgesics/therapeutic use, Anti‐Ulcer Agents, Anti‐Ulcer Agents/therapeutic use, Low‐Level Light Therapy, Low‐Level Light Therapy/methods, Mouth Diseases, Mouth Diseases/etiology, Mouth Diseases/therapy, Neoplasms, Neoplasms/drug therapy, Neoplasms/radiotherapy, Oral Ulcer, Oral Ulcer/etiology, Oral Ulcer/therapy, Pain, Pain/etiology, Pain Management, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Stomatitis, Stomatitis/etiology, Stomatitis/therapy

Interventions for treating oral mucositis for patients with cancer receiving treatment

Using a low level laser may reduce the severity of ulcers caused by cancer treatment. Treatments for cancer can cause severe ulcers (sores) in the mouth. These can be painful and slow to heal. The review found some evidence that using a laser relieves or cures the ulcers. Morphine can control the pain. Although using morphine automatically on a constant drip, or self controlled use, provide similar relief, people use less morphine when they are controlling it themselves.

Background

Treatment of malignant diseases with cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both, is becoming increasingly more effective but it is associated with short and long term side effects. Among the clinically important acute side effects is disruption in the function and integrity of the oral mucosa. The consequences of this include severe ulceration (oral mucositis) and fungal infection of the mouth (oral candidiasis). These disease and treatment induced complications may also produce oral discomfort and pain, poor nutrition, delays in administration of chemotherapy or radiotherapy, reductions in the doses of chemotherapy drugs, increased length of inpatient stays and associated economic costs and in some patients life threatening infection (septicaemia in neutropenic patients).

Oral complications remain a major source of illness despite the use of a variety of agents to prevent them. There are variations in usage between cancer centres in terms of the mouthcare regimen used. Compliance with recommended use of product is variable and there are conflicting reports of the effectiveness of prophylactic agents. The qualitative and quantitative benefits, side effects and costs of oral therapies are of importance to the cancer teams responsible for the treatment of patients.

There have been several traditional reviews published and most of these present a general discussion for both chemotherapy and radiotherapy induced oral side effects (De Pauw 1997; Denning 1992; Knox 2000; Lortholary 1997; Plevova 1999; Shaw 2000; Stevens 1995; Symonds 1998; Verdi 1993; White 1993). The conclusions drawn and recommendations made vary from advocating a particular therapy to recommending oral care procedures that have not been systematically investigated. Five systematic reviews, which were not Cochrane reviews, have focused on the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis in patients with cancer. One older review published in 1998 concluded that for most strategies reviewed there is insufficient evidence to draw any conclusions regarding their effectiveness (Kowanko 1998). The other three more recent reviews focused on patients with head and neck cancer only (Shih 2002; Sutherland 2001; Trotti 2003), and two were unable to draw definite conclusions regarding the effectiveness of any of the agents tested, however in the Sutherland 2001 review the main analysis combined all the interventions in one meta‐analysis and found a beneficial effect of prophylactic interventions. This pooling of interventions is impossible to interpret and therefore not helpful.

A systematic review looking at antimicrobial therapy to prevent or treat mucositis identified 31 prospective trials (not just randomised trials) of which 13 reported some benefit. The review concludes that there is no clear pattern emerging regarding the benefit or otherwise of antimicrobial use to manage mucositis, and there is limited evidence supporting the use of antimicrobial agents for reducing oral mucositis (Donnelly 2003).

Another review looked at granulocyte macrophage‐colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) for the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis (Fung 2002). This review included studies of different types including some with historical controls. The authors conclude that although there are published studies, these studies are limited and the use of systemic or topical GM‐CSF cannot be recommended for prevention or treatment of mucositis.

This review is part of a series of four Cochrane reviews looking at the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis and oral candidiasis in patients with cancer receiving treatment (Worthington 2007a; Clarkson 2007; Worthington 2007b). The review for the prevention of oral mucositis (Worthington 2007b) found 11 out of the 33 interventions investigated showed some evidence of a benefit (albeit sometimes weak) for either preventing or reducing the severity of mucositis. Interventions with more than one trial were amifostine, Chinese medicine, hydrolytic enzymes and ice chips (cryotherapy). Interventions with only one study were: benzydamine, calcium phosphate, etoposide bolus, honey, iseganan, oral care and zinc sulphate. This review is currently being updated and will be published in 2010.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions (which may include placebo or no treatment) for the treatment of oral mucositis or its associated pain for patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both. The following null hypotheses were tested, against alternative hypotheses of a difference, for comparisons between groups treated for mucositis.

There is no difference in the proportion of patients with improvement in mucositis after treatment for mucositis.

There is no difference in the proportion of patients with mucositis eradicated after treatment for mucositis.

There is no difference in the proportion of patients with severe mucositis (≥grade 3) after treatment for mucositis

There is no difference in the mean number of days taken to heal.

There is no difference in the mean pain scores after treatment or analgesia for mucositis.

The review is divided into two parts, one concerning interventions for the treatment of mucositis and one concerning the control of the pain in patients with mucositis. In this review we also addressed the hypothesis of no difference between groups treated for mucositis for the following outcomes if data were available from studies which included a primary outcome:

relief of dysphagia (problems during eating);

incidence of systemic infection;

amount of analgesia;

days stay in hospital;

cost of oral care;

patient quality of life.

The following subgroup analyses were proposed a priori:

cancer type (head and neck, other solid tumours, leukaemia, and mixed);

cancer treatment type;

age group (children, adults, children and adults).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion in this review.

Types of participants

Anyone with cancer who is receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both and has oral mucositis.

Types of interventions

Active agents: any intervention for the treatment of oral mucositis or its associated pain. Control: may be placebo, no treatment, or another active intervention.

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes were considered in this review:

Mucositis at different levels of severity

Days to heal (mean)

Oral pain scores or categories

Relief of dysphagia

Incidence of systemic infection

Amount of analgesia

Days stay in hospital

Cost of oral care

Patient quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

This review is part of a series of four reviews on the prevention and treatment of oral candidiasis and oral mucositis in patients with cancer, and the same search strategies were used for all four reviews. The searches attempted to identify all relevant trials irrespective of language. Papers not in English were translated by members of The Cochrane Collaboration. Sensitive search strategies were developed for each database using a combination of free text and MeSH terms. The MEDLINE and CANCERLIT searches combined the subject search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity maximising version (2009 revision) as referenced in Chapter 6.4.11.1 and detailed in boxes 6.4a and 6.4.c of The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009] (Higgins 2009). The EMBASE and CINAHL searches were combined with sensitive search strategies developed by the Cochrane Oral Health Group for identifying RCTs. The LILACs subject search was combined with the Brazilian Cochrane Centre search strategy for identifying RCTs in LILACS.

Electronic searching ‐ the databases searched were: Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register (to 1 June 2010) (see Appendix 1) Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care (PaPaS) Group Trials Register (to 1 June 2010) (see Appendix 1) Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 2, 1 June 2010) (see Appendix 2) MEDLINE and MEDLINE Pre‐indexed via OVID (1950 to 1 June 2010) (see Appendix 3) EMBASE via OVID (1980 to 1 June 2010) (see Appendix 4) CINAHL via EBSCO (1980 to 1 June 2010) (see Appendix 5) CANCERLIT via PubMed (1950 to 1 June 2010) (see Appendix 6) OpenSIGLE (1980 to 1 June 2010) (see Appendix 7) LILACS via The Virtual Health Library (see Appendix 8).

Only handsearching carried out by The Cochrane Collaboration was included in the search (see master list www.cochrane.org).

The controlled trials database (www.controlled‐trials.com) was also searched to identify ongoing and completed trials and to contact trialists for further information about these trials.

The reference list of related review articles and all articles obtained were checked for further trials. Authors of trial reports and specialists in the field known to the review authors were written to concerning further published and unpublished trials.

The review will be updated every 2 years using the Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, CANCERLIT and LILACS. The search of OpenSIGLE was discontinued as this database ceased being updated in 2005.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The titles and abstracts (when available) of all reports identified through the searches were scanned by two review authors. Full reports were obtained for trials appearing to meet the inclusion criteria or for which there was insufficient information in the title and abstract to make a clear decision. The full reports obtained from all the electronic and other methods of searching were assessed independently, in duplicate, by two review authors to establish whether the trials met the inclusion criteria or not. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by two review authors independently using specially designed data extraction forms. The characteristics of the trial participants, interventions and outcomes for the included trials are presented in the study tables. Mucositis may be dichotomised at different levels of severity. In order to maximise the availability of similar outcome data, we recorded the number of patients in each category of mucositis usually on a 0 to 4 scale, and used the following dichotomies: 0 versus 1+, 0‐1 versus 2+, 0‐2 versus 3+. Pain was assessed on visual analogue scales (0 to 100), the means and standard deviations for each group were recorded. The duration of trials and timing of assessments were recorded in order to make a decision about which to include for commonality. We also recorded the country where the trial was conducted and whether a dentist was involved in the investigation. Authors of full study reports and abstracts identified were contacted for clarification or for further information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

This was conducted using the recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane reviews (Higgins 2009). It is a two‐part tool, addressing the six specific domains (namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and ‘other issues’). Each domain includes one or more specific entries in a ‘Risk of bias’ table. Within each entry, the first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry. This is achieved by answering a pre‐specified question about the adequacy of the study in relation to the entry, such that a judgement of ‘Yes’ indicates low risk of bias, ‘No’ indicates high risk of bias, and ‘Unclear’ indicates unclear or unknown risk of bias.

The domains of sequence generation, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting are each addressed in the tool by a single entry for each study. For blinding two entries were used because assessments need to be made separately for a) patients and carers and b) outcome assessor. The final domain (‘other sources of bias’) was assessed as a single entry for studies as a whole.

The risk of bias assessment was undertaken independently and in duplicate by two review authors as part of the data extraction process.

Summarising risk of bias for a study:

After taking into account the additional information provided by the authors of the trials, studies were grouped into the following categories. We assumed that the risk of bias was the same for all outcomes and each study was assessed as follows:

| Risk of bias | Interpretation | Within a study | Across studies |

| Low risk of bias. | Plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results. | Low risk of bias for all key domains. | Most information is from studies at low risk of bias. |

| Unclear risk of bias. | Plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results. | Unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains. | Most information is from studies at low or unclear risk of bias. |

| High risk of bias. | Plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results. | High risk of bias for one or more key domains. | The proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias is sufficient to affect the interpretation of results. |

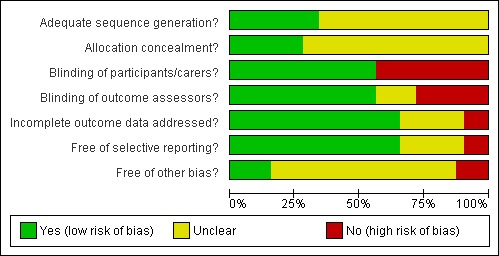

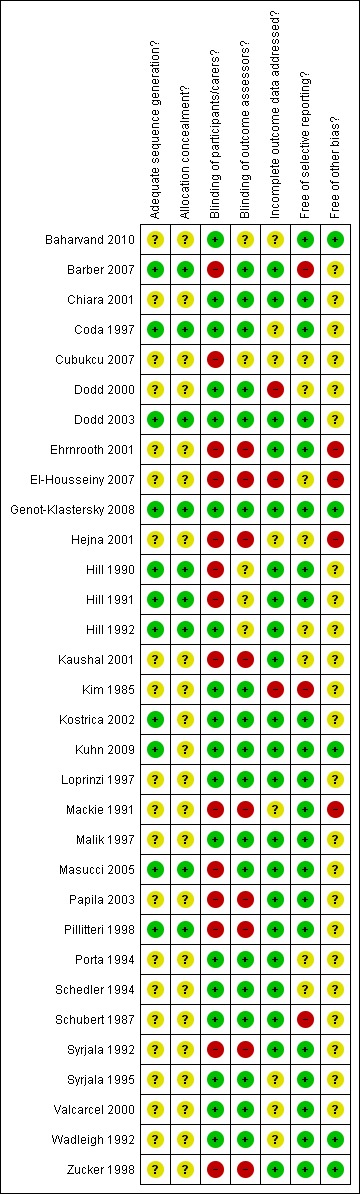

A risk of bias table was completed for each included study (Risk of bias in included studies). Results are presented graphically by study (see Figure 1) and by domain over all studies (Figure 2) .

Figure 1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Measure of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, the estimates of effect of an intervention were expressed as risk ratios together with 95% confidence intervals. For continuous outcomes mean differences together with 95% confidence intervals were used.

Dealing with missing data

Intention‐to‐treat analyses were conducted if possible. Methods outlined the handbook (Higgins 2009) were used to impute missing standard deviations if these could not be obtained from authors.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The significance of any discrepancies in the estimates of the treatment effects from the different trials was assessed by means of Cochran's test for heterogeneity and quantified by I2 statistics. Heterogeneity was considered statistically significant if P value was < 0.1. A rough guide to the interpretation of I2 given in the Handbook is: 0 to 40% might not be important, 30 to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50 to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity, 75 to 100% considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2009).

Assessment of reporting biases

We tabulated all the outcomes considered here.

Data synthesis

Meta‐analyses were done only with studies of similar comparisons. Risk ratios were combined for dichotomous data using random‐effects models (fixed‐effect models used if less than 3 studies in meta‐analysis).

It was planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of concealed allocation and blind outcome assessment on the overall estimates of effect. However there were insufficient trials to undertake this.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We proposed a priori to conduct subgroup analyses for different cancer types (head and neck, other solid tumours, haematological and mixed), cancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy) and age groups (children, adults and mixed).

We planned to investigate clinical heterogeneity by examining the different cancer types and age groups.

Results

Description of studies

SeeCharacteristics of included studies table. SeeCharacteristics of excluded studies table.

Electronic searches identified over 6000 titles and abstracts and from this we obtained over 600 full reports. Ninety‐five studies were considered eligible according to the defined criteria for trial design, participants, interventions and outcomes.

Characteristics of the trial setting and investigators

Of the 95 eligible studies, 64 were subsequently excluded for the following reasons:

not randomised controlled trial (RCT) (12 studies);

abstract only (27 studies: where possible authors were contacted for further information but no replies were received);

unsuitable design (14 studies: reasons include: trial stopped when obtained result (unplanned), all patients allocated but only given intervention if they had mucositis, cross‐over but unsure if mucositis at second period);

protocol violation (1 study: recruitment was halted early due to ethical concerns relating to rinse);

no useable data (6 studies: progression of mucositis, number of ulcers, area covered, means);

no relevant outcomes (3 studies);

unclear information on number of withdrawals (1 study).

Of the 32 included trials, 13 were conducted in USA (Coda 1997; Dodd 2000; Dodd 2003; Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992; Kim 1985; Loprinzi 1997; Mackie 1991; Schubert 1987; Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995; Wadleigh 1992), two in Germany (Schedler 1994; Zucker 1998), two in Italy (Chiara 2001; Porta 1994), two in the UK (Barber 2007; Pillitteri 1998), two in Turkey (Cubukcu 2007; Papila 2003), and one each in Pakistan (Malik 1997), Denmark (Ehrnrooth 2001), Austria (Hejna 2001), India (Kaushal 2001), Iran (Baharvand 2010), Czech Republic (Kostrica 2002), Sweden (Masucci 2005), Egypt (El‐Housseiny 2007), Belgium (Genot‐Klastersky 2008), Brazil (Kuhn 2009) and Spain (Valcarcel 2000). Six of the trials were multicentre studies (Baharvand 2010; Barber 2007; Dodd 2003; Loprinzi 1997; Masucci 2005; Schubert 1987). Twenty of the trials received external funding, 10 obtained government funding, nine acknowledged assistance from the pharmaceutical industry (Dodd 2003; Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Kim 1985; Mackie 1991; Malik 1997; Masucci 2005; Schubert 1987; Valcarcel 2000). The providers and assessors of the treatments were mainly medical staff although seven of the trials involved a dentist (Cubukcu 2007; Dodd 2000; Dodd 2003; Kuhn 2009; Masucci 2005; Schubert 1987; Wadleigh 1992), four a hygienist (Coda 1997; Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992) and in two trials only patients were involved in the mucositis assessment (Dodd 2000; Loprinzi 1997).

Characteristics of the participants

Twenty‐eight of the 32 included trials recruited only adult patients with cancer, four included only children (Cubukcu 2007; El‐Housseiny 2007; Kuhn 2009; Mackie 1991). Fourteen trials included patients treated for a combination of leukaemia and solid tumours, eight trials included patients with head and neck cancer (Barber 2007; Dodd 2003; Ehrnrooth 2001; Kaushal 2001; Kim 1985; Kostrica 2002; Masucci 2005; Schedler 1994), a further six trials only treated patients with solid cancers (Chiara 2001; Cubukcu 2007; Dodd 2000; Hejna 2001; Papila 2003; Porta 1994) and two trials included patients with leukaemia only (Genot‐Klastersky 2008; Valcarcel 2000). The cancer type was unclear in two trials (Baharvand 2010; El‐Housseiny 2007). The patients in 11 trials received bone marrow transplants and stem cell transplants (Coda 1997; Genot‐Klastersky 2008; Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992; Mackie 1991; Pillitteri 1998; Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995; Valcarcel 2000; Zucker 1998). The patients in 22 trials received chemotherapy only (Baharvand 2010; Chiara 2001; Coda 1997; Cubukcu 2007; Dodd 2000; El‐Housseiny 2007; Hejna 2001; Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992; Kuhn 2009; Loprinzi 1997; Mackie 1991; Malik 1997; Papila 2003; Pillitteri 1998; Porta 1994; Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995; Valcarcel 2000; Wadleigh 1992; Zucker 1998), in eight trials the patient received only radiotherapy (Barber 2007; Dodd 2003; Ehrnrooth 2001; Kaushal 2001; Kim 1985; Kostrica 2002; Masucci 2005; Schedler 1994) and in two trials the patient received both chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Genot‐Klastersky 2008; Schubert 1987).

Although the reporting of the reasons for withdrawal by study group was unclear in nine trials, the percentage of withdrawals was clear in all trials apart from two and this ranged from 0% to 60% with a median of 9%.

Characteristics of the interventions

Treatment of mucositis

Twenty‐one trials looked at the effectiveness of 15 agents treating clinical signs of mucositis. Ten of these were placebo controlled trials and a further 11 trials had other comparisons as shown below:

allopurinol versus placebo (Porta 1994);

benzydamine HCl versus placebo (Kim 1985; Schubert 1987);

chlorhexidine versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000);

debridement versus no debridement (Cubukcu 2007);

Gelcaire versus sucralfate and mucaine (Barber 2007);

GM‐CSF (granulocyte macrophage‐colony stimulating factor) versus no treatment (Masucci 2005);

GM‐CSF versus placebo (Valcarcel 2000);

GM‐CSF versus povidone iodine (Hejna 2001);

GM‐CSF versus antimycotic mouthrinse (Papila 2003);

human placental extract versus Disprin™ (Kaushal 2001);

laser versus sham treatment (Genot‐Klastersky 2008;Kuhn 2009);

'magic' (lidocaine solution, diphenhydramine hydrochloride and aluminium hydroxide suspension) versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000);

phenytoin mouthrinse versus placebo (Baharvand 2010);

polyvariant intramuscular immunoglobulin versus placebo (Schedler 1994);

sucralfate versus placebo (Chiara 2001; Loprinzi 1997);

sucralfate versus salt and soda (Dodd 2003);

tetrachlorodecaoxide versus placebo (Malik 1997);

vitamin E versus placebo (Wadleigh 1992);

vitamin E (topical) versus vitamin E (swallowed) (El‐Housseiny 2007).

Control of mucositis pain

Fourteen trials examined the effectiveness of pain control in patients with mucositis (Baharvand 2010; Coda 1997; Dodd 2000; Dodd 2003; Ehrnrooth 2001; Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992; Kostrica 2002; Mackie 1991; Pillitteri 1998; Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995; Zucker 1998). Fourteen different agents were assessed, trials frequently looking at different methods of delivery of the same agent. Seven trials included a group receiving morphine and four trials compared patient controlled versus continuous infusion of pain control. All the comparisons are shown below:

alfentanil versus morphine (Hill 1992);

hydromorphone versus morphine (Coda 1997);

sufentanil versus morphine (Coda 1997);

morphine versus tricyclic antidepressant (Ehrnrooth 2001);

sufentanil versus hydromorphone (Coda 1997);

patient controlled analgesia (PCA) versus continuous infusion delivery of morphine (Hill 1990; Mackie 1991; Pillitteri 1998);

pharmacokinetically based patient controlled analgesic infusion system (PKPCA) versus PCA for delivery of morphine (Hill 1991);

PCA versus staff controlled delivery of pethidine (Zucker 1998);

diclofenac versus placebo (Kostrica 2002);

therapist versus control (Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995);

relaxation and imagery therapy versus control (Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995);

cognitive behaviour versus control (Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995);

hypnosis versus control (Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995);

chlorhexidine versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000);

'magic' (lidocaine solution, diphenhydramine hydrochloride and aluminium hydroxide suspension) versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000);

sucralfate versus salt and soda (Dodd 2003);

phenytoin mouthrinse versus placebo (Baharvand 2010).

Characteristics of outcome measures

Treatment of mucositis

Nine trials looked at whether the mucositis had improved (Chiara 2001; El‐Housseiny 2007; Kaushal 2001; Kim 1985; Malik 1997; Masucci 2005; Porta 1994; Schedler 1994; Schubert 1987) and seven trials reported whether the mucositis was eradicated completely (Baharvand 2010; Chiara 2001; Dodd 2000; El‐Housseiny 2007; Loprinzi 1997; Porta 1994; Wadleigh 1992). Three trials looked at mild to moderate (rather than severe) mucositis (Barber 2007; Genot‐Klastersky 2008; Kuhn 2009). Six trials reported the mean number of days to heal the mucositis (Dodd 2000; Dodd 2003; Hejna 2001; Papila 2003; Porta 1994; Valcarcel 2000). Six trials used WHO criteria for mucositis on a 0 to 4 scale, where 0 = none, 1 = erythema/soreness, 2 = ulcer and able to eat, 3 = ulcer and limited eating, 4 = ulcer with haemorrhage and necrosis (Cubukcu 2007; El‐Housseiny 2007; Loprinzi 1997; Malik 1997; Porta 1994; Wadleigh 1992). Two trials used NCI Common Toxicity Criteria (Baharvand 2010; Barber 2007), and a further trial the EORTC scale (Genot‐Klastersky 2008). Two trials used a scale with no specific criteria as follows: none, slight, moderate and severe mucositis (Kim 1985; Kostrica 2002). A final trial reported the proportion of patients with an improvement in mucositis pain (Schubert 1987). This trial was included with other trials which dichotomised mucositis as improved or not.

Control of mucositis pain

Twelve of the 14 trials on pain control (Baharvand 2010; Coda 1997; Ehrnrooth 2001; Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992; Kostrica 2002; Mackie 1991; Pillitteri 1998; Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995; Zucker 1998) used a patient scored visual analogue scale, with Dodd 2000 using a 0 (no soreness) to 10 (very sore) scale which could be converted into a 0 to 100 scale, and Dodd 2003 a 0 to 3 scale.

The mean and standard deviations for mucositis pain were presented at different time points: average over 2 to 5 days (Coda 1997); daily up to 7 days (Dodd 2000); average for worst mucositis (Dodd 2003); 7 and 14 days post radiotherapy (Ehrnrooth 2001); 7 and 14 days post start of treatment (Baharvand 2010); daily up to day 9 (Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992); daily up to day 28 (Kostrica 2002); daily up to day 18 (Mackie 1991); daily up to day 14 (Pillitteri 1998); average over 3 weeks (Syrjala 1992); average from days 6 to day 16 (Syrjala 1995); mean pain score over treatment (Zucker 1998). We decided to use the time point 7 days after the start of treatment for mucositis as these data was available for most trials, otherwise we used the nearest time point reported. Four trials presented data on mean morphine utilisation (mg/hour) for day 7 (Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992; Pillitteri 1998). Two trials presented the data in a different form, one as mean mg of morphine/day averaged over each week of the trial (Syrjala 1992) and a further trial presented the data as mg of morphine/kg/hour (Mackie 1991).

Three trials reported the duration of the pain control therapy (Hill 1990; Mackie 1991; Pillitteri 1998). Only two trials reported other outcome measures which were related to oral function and ability to eat (Kim 1985; Malik 1997).

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the risk of bias assessments appears in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The concealment of allocation was adequate for nine (28%) of the 32 trials and it was unclear for the remaining 23; in no trials was this considered inadequate. In seven trials assessing pain the patient could not be blinded to the intervention. The outcome assessor was blinded for 18 of the remaining 24 trials. Twenty‐one trials gave a clear description of withdrawals by trial group, this being unclear in the remaining trials. Letters were sent to authors of the trials where clarification was needed and seven replies were received (Dodd 2003; Hejna 2001; Hill 1990; Loprinzi 1997; Masucci 2005; Pillitteri 1998; Valcarcel 2000), with the information supplied changing the assessment of concealed randomisation from unclear to adequate in five studies (Dodd 2003; Genot‐Klastersky 2008; Hill 1990; Hill 1991; Hill 1992).

The validity of each study was assessed as at low, unclear or high risk of bias. Four studies were rated as at low risk of bias (Coda 1997; Dodd 2003; Genot‐Klastersky 2008;Hill 1992), six assessed as unclear (Barber 2007; Hill 1990;Hill 1991;Kuhn 2009; Masucci 2005; Pillitteri 1998) and the remaining 22 trials at high risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

For the 32 trials included in the review 1505 patients were randomised and provide data for this review. This comprised 1023 patients participating in the 20 trials investigating the effectiveness of agents to treat mucositis and 718 in the 14 trials evaluating pain relief, with some trials providing data for more than one of these outcomes. The number of patients ranged from 6 to 71 per treatment or control group.

Treatment of mucositis

The following comparisons only included one trial for one or more of the mucositis outcomes. As this review is concerned with the meta‐analysis of trials we have summarised the data from single trials below by indicating any which showed a significant benefit for the active intervention (further data is given in Table 7):

Table 1.

Data from comparisons and outcomes with single trials

| Experimental | Control | RR/MD (95%CI) | P value | ||||

| Events/ Mean (SD) | Total | Events/Mean (SD) | Total | ||||

| Allopurinol mouthwash versus placebo (Porta 1994) |

Improvement in mucositis |

19 | 22 | 3 | 22 | RR 6.33 (2.18, 18.37) | 0.0007 |

| Mucositis eradicated |

9 | 22 | 0 | 22 | RR 19.00 (1.17, 307.63) | 0.04 | |

| Time to heal mucositis (days) |

4 (1.16) | 22 | 8.5 (2.82) | 22 | MD ‐4.50 (‐5.77, ‐3.23) | < 0.001 | |

| Chlorhexidine versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000) |

Mucositis eradicated |

51 | 67 | 49 | 71 | RR 1.10 (0.90, 1.35) | 0.35 |

| Time to heal mucositis (days) |

6.6 (2.57) | 51 | 7.0 (2.99) | 49 | MD ‐0.40 [‐1.49, 0.69] | 0.47 | |

| Average pain scores |

11.3 (20.1) | 32 | 14.8 (19.8) | 31 | MD ‐3.50 [‐13.35, 6.35] | 0.49 | |

| Gelclair versus sucralfate and mucaine (Barber 2007) |

Mild to moderate mucositis |

3 | 10 | 6 | 10 | RR 0.50 [0.17, 1.46] | 0.21 |

| GM‐CSF versus no treatment (Mascucci 2005) |

Improvement in mucositis at 14 days |

11 | 29 | 4 | 22 | RR 2.09 [0.77, 5.68] |

0.15 |

| Improvement in mucositis at end of radiotherapy | 14 | 32 | 3 | 29 | RR 4.23 (1.35, 13.24) | 0.01 | |

| GM‐CSF versus placebo (Valcarcel 2000) |

Time to heal mucositis (days) |

11.4 (4.00) | 16 | 12.5 (3.4) | 19 | MD ‐1.10 (‐3.59, 1.39) | 0.39 |

| GM‐CSF versus povidone iodine (Henja 2001) |

Time to heal mucositis (days) |

2.8 (0.7) | 15 | 6.3 (1.1) | 16 | MD ‐3.50 [‐4.14, ‐2.86] | < 0.001 |

| GM‐CSF versus antimycotic mouthwash (Papila 2003) |

Time to heal mucositis (days) |

3.95 (2.01) | 20 | 6.35 (3.44) | 20 | MD ‐2.40 [‐4.15, ‐0.65] |

0.007 |

| Human placental extract versus DisprinTM (Kaushal 2001) |

Improvement in mucositis | 36 | 60 | 8 | 60 | RR 4.50 [2.29, 8.86] | < 0.001 |

| ‘Magic’ versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000) |

Mucositis eradicated |

42 | 62 | 49 | 71 | RR 0.98 [0.78, 1.24] |

0.88 |

| Time to heal mucositis (days) |

7.17 (2.57) | 42 | 7.00 (2.99) | 49 | MD 0.17 [‐0.97, 1.31] | 0.77 | |

| Average pain scores |

14.2 (19.8) |

26 | 14.8 (19.8) | 31 | MD ‐0.60 [‐10.92, 9.72] | 0.91 | |

| Phenytoin mouthrinse versus placebo (Baharvand 2010) | Average pain scores | 1.5 (2.4) | 6 | 3.2 (1.2) | 6 | MD ‐1.70 [‐3.85, 0.45] | 0.12 |

| Quality of Life | 51.7 (4.8) | 6 | 66.8 (12.8) | 6 | MD ‐15.10 [‐26.04,‐4.16] | 0.007 | |

| Polyvariant intramuscular immunoglobulin versus placebo (Schedler 1994) |

Improvement in mucositis | 31 | 39 | 18 | 41 | RR 1.81 [1.24, 2.65] |

0.002 |

| Sucralfate versus placebo (Chiara 2001) |

Improvement in mucositis | 14 | 17 | 15 | 17 | RR 0.93 [0.71, 1.24] |

0.63 |

| Sucralfate versus salt and soda (Dodd 2003) |

Time to heal mucositis (days) | 70.8 (28.9) | 13 | 57.7 (22.5) | 15 | MD 13.10 [‐6.30, 32.50] | 0.19 |

| Average pain intensity | 2.1 (1.1) | 14 | 2.4 (0.9) | 15 | MD ‐0.30 [‐1.03, 0.43] | 0.42 | |

| Tetrachlorodecaoxide versus placebo (Malik 1997) |

Improvement in mucositis | 29 | 32 | 22 | 30 | RR 1.24 [0.97, 1.58] |

0.09 |

| Vitamin E versus (not true) placebo (Wadleigh 1992) |

Mucositis eradicated |

6 | 9 | 1 | 9 | RR 6.00 [0.89, 40.31] |

0.07 |

| Vitamin E (topical) versus vitamin E (swallowed) at 5 days (El‐Housseiny 2007) | Improvement in mucositis | 28 | 30 | 2 | 33 | RR 15.40 [4.01, 59.21] |

< 0.001 |

| Mucositis eradicated |

24 | 30 | 0 | 33 | RR 53.74 [3.41, 846.84] | 0.005 | |

| Alfentanil (PKPCA) versus morphine (PKPCA) (Hill 1992) |

Average pain scores |

48.0 (52.0) | 12 | 48.0 (20.0) | 16 | MD 0.00 [‐31.01, 31.01] | 1.00 |

| Daily mean opiate intake per hour |

2.3 (2.8) | 12 | 6.2 (4.0) | 16 | MD ‐3.90 [‐6.42, ‐1.38] |

0.002 | |

| Hydromorphone (PCA) versus morphine (PCA)) (Coda 1997) |

Average pain scores |

48.9 (19.9) | 27 | 48.3 (17.5) | 29 | MD 0.60 (‐9.24, 10.44) | 0.90 |

| Sufentanil (PCA) versus morphine (PCA) (Coda 1997) |

Average pain scores |

53.7 (16.0) | 31 | 48.3 (17.5) | 29 | MD 5.40 [‐3.10, 13.90) | 0.21 |

| Opioid versus antidepressant (Ehrnrooth 2001) |

Average pain scores |

33.5 (17.7) |

20 | 52.6 (20.1) | 19 | MD ‐19.10 [‐31.01, ‐7.19] | 0.002 |

| Morphine (PKPCA) versus morphine (PCA) (Hill 1991) |

Average pain scores |

48.0 (19.0) | 15 | 66.0 (22.0) | 20 | MD ‐18.00 [‐31.62, ‐4.38] | 0.01 |

| Daily mean opiate intake per hour |

6.4 (3.9) | 15 | 2.8 (1.8) | 20 | MD 3.60 [1.47, 5.73) | 0.0009 | |

| PCA versus staff controlled (pethidine) (Zucker 1998) |

Average pain scores |

41.0 (24.0) |

10 | 62.032.0 | 10 | MD ‐21.00 [‐45.79, 3.79] | 0.10 |

| Daily mean opiate intake per hour |

17.0 (7.0) | 10 | 21.0 (7.0) | 10 | MD ‐4.00 [‐10.14, 2.14) | 0.20 | |

| Diclofenic versus placebo (Kostrica 2002) |

Average pain scores |

0.75 (1.17) | 32 | 1.05 (1.17) | 34 | MD ‐0.30 [‐0.86, 0.26] | 0.30 |

| Therapist versus control (Syrjala 1992) |

Daily mean opiate intake per hour |

1.86 (5.0) | 12 | 1.66 (5.4) |

10 | MD 0.20 [‐4.18, 4.58 | 0.93 |

| Relaxation and imagery versus control (Syrjala 1995) |

Average pain scores |

45.56 (23.7) | 23 | 53.78 (23.25) | 23 | MD ‐8.22 [‐21.79, 5.35] | 0.24 |

| Cognitive behaviour versus control (Syrjala 1992) |

Daily mean opiate intake per hour | 1.46 (3.98) | 11 | 1.66 (5.4) | 10 | MD ‐0.20 [‐4.29, 3.89] | 0.92 |

| Hypnosis versus control (Syrjala 1992) |

Average pain scores |

23.0 (31.1) | 12 | 33.5 (29.9) | 10 | MD ‐10.50 [‐36.05, 15.05] | 0.42 |

| Daily mean opiate intake per hour | 1.21 (3.78) | 12 | 1.66 (5.4) | 10 | MD ‐0.45 [‐4.42, 3.52] | 0.82 | |

allopurinol versus placebo (Porta 1994: statistically significant benefit in favour of allopurinol for improvement in mucositis, eradication and time to heal);

chlorhexidine versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000: no statistically significant difference);

debridement versus no debridement (Cubukcu 2007: statistically significant benefit for debridement for days to clinical resolution and decreased severity);

Gelcaire versus sucralfate and mucaine (Barber 2007: no statistically significant difference);

GM‐CSF (granulocyte macrophage‐colony stimulating factor) versus no treatment (Masucci 2005: statistically significant benefit for improvement in mucositis at end of radiotherapy);

GM‐CSF versus placebo (Valcarcel 2000: no statistically significant difference);

GM‐CSF versus povidone iodine (Hejna 2001: statistically significant benefit for GM‐CSF for time to heal);

GM‐CSF versus antimycotic mouthrinse (Papila 2003: statistically significant benefit for GM‐CSF for time to heal);

human placental extract versus Disprin™ (Kaushal 2001: statistically significant benefit for human placental extract for improvement in mucositis);

'magic' (lidocaine solution, diphenhydramine hydrochloride and aluminium hydroxide suspension) versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000: no statistically significant differences);

phenytoin mouthrinse versus placebo (Baharvand 2010: statistically significant difference in quality of life at 7 days favouring phenytoin);

polyvariant intramuscular immunoglobulin versus placebo (Schedler 1994: statistically significant benefit for the immunoglobulin for improvement of mucositis);

sucralfate versus salt and soda (Dodd 2003: no statistically significant difference);

tetrachlorodecaoxide versus placebo (Malik 1997: no statistically significant difference);

vitamin E versus placebo (Wadleigh 1992: no statistically significant difference);

vitamin E (topical) versus vitamin E (swallowed) (El‐Housseiny 2007: statistically significant benefit for the topical vitamin E for improvement of mucositis).

The comparisons below include more than one trial for some of the outcomes measured and the results of the meta‐analysis are presented:

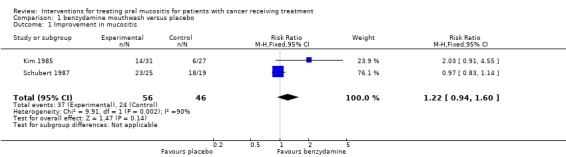

Benzydamine HCl versus placebo

Two trials (Kim 1985; Schubert 1987) provided data (Analysis 1.1) for improvement in mucositis and there was no statistically significant difference between benzydamine and placebo with risk ratio (RR) 1.22 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.94 to 1.60). Both trials were assessed as at high risk of bias. Schubert 1987 noted a lack of power in this study.

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 benzydamine mouthwash versus placebo, Outcome 1 Improvement in mucositis.

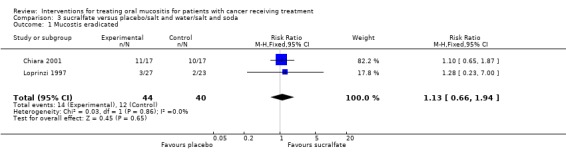

Sucralfate versus placebo

Two trials (Chiara 2001; Loprinzi 1997) provided data for eradication of mucositis (Analysis 3.1) and there was no statistically significant difference between sucralfate and placebo with RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.94). One trial was assessed as at unclear risk of bias, the other at high risk of bias.

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 sucralfate versus placebo/salt and water/salt and soda, Outcome 1 Mucostis eradicated.

Laser versus sham treatment

Two trials (Genot‐Klastersky 2008;Kuhn 2009) provided data (Analysis 2.1) for the outcome of mild to moderate mucositis and there was a statistically significant benefit for the laser with RR 5.28 (95% CI 2.30 to 12.13). One trial was assessed as at low risk of bias the other as at unclear risk of bias.

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 low level laser versus sham, Outcome 1 Mild to moderate mucositis.

Control of mucositis pain

As above the comparisons below only included one trial for the pain outcomes (further data given in Table 7):

alfentanil versus morphine (Hill 1992: statistically significant difference in favour of alfentanil for daily mean opiate intake);

hydromorphone versus morphine (Coda 1997: no statistically significant difference);

sufentanil versus morphine (Coda 1997: no statistically significant difference);

morphine versus tricyclic antidepressant (Ehrnrooth 2001: statistically significant difference in favour of morphine for less pain);

sufentanil versus hydromorphone (Coda 1997: no statistically significant difference);

pharmacokinetically based patient controlled analgesic infusion system (PKPCA) versus PCA for delivery of morphine (Hill 1991: statistically significant difference in favour of PKPCA morphine for less pain but more opiate per hour);

PCA versus staff controlled delivery of pethidine (Zucker 1998: no statistically significant differences);

phenytoin mouthrinse versus placebo (Baharvand 2010: no statistically significant difference);

diclofenac versus placebo (Kostrica 2002: no statistically significant difference);

relaxation and imagery therapy versus control (Syrjala 1995: no statistically significant difference);

hypnosis versus control (Syrjala 1992: no statistically significant differences);

chlorhexidine versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000: no statistically significant difference);

'magic' (lidocaine solution, diphenhydramine hydrochloride and aluminium hydroxide suspension) versus salt and soda (Dodd 2000: no statistically significant difference);

sucralfate verus salt and soda (Dodd 2003: no statistically significant difference).

The comparisons below include more than one trial for some of the outcomes measured and the results of the meta‐analysis are given below:

Patient controlled analgesia (PCA) versus continuous infusion delivery of morphine

Three trials (Hill 1990; Mackie 1991; Pillitteri 1998) provide data for mean pain score (7 day data used for Pillitteri 1998) (Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3). The meta analysis showed no statistically significant difference in mean pain score with a mean difference (on 0 to 100 scale) of ‐2.49 (95% CI ‐12.28 to 7.29). The three trials also provided data for daily mean opiate intake mg per hour and this outcome showed a statistically significant reduction in mean opiate intake favouring the PCA morphine group, with a mean difference (reduction) of 0.65 mg/hour (95% CI 0.09 to 1.20) (P = 0.02). The trials also provided data on the duration of pain control (days) and the meta‐analysis showed a statistically significant reduction in days of pain favouring PCA, with a mean difference of ‐1.87 (95% CI ‐3.49 to ‐0.25) (P = 0.02). There was no evidence of heterogeneity between the effects for the three studies for either mean opiate intake or duration (P > 0.50, I2 = 0). However two of the three trials were assessed as unclear risk of bias and one as at high risk of bias (Mackie 1991).

Analysis 4.1.

Comparison 4 morphine (PCA) versus morphine (CI), Outcome 1 Average pain score.

Analysis 4.2.

Comparison 4 morphine (PCA) versus morphine (CI), Outcome 2 Daily mean opiate intake per hour.

Analysis 4.3.

Comparison 4 morphine (PCA) versus morphine (CI), Outcome 3 Duration of pain control.

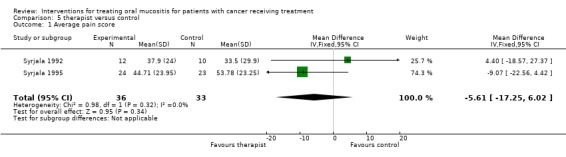

Therapist versus control

Two trials (Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995) provided data (Analysis 5.1) for average pain score but the meta analysis showed no statistically significant difference between the group who received therapist visits and the control group who received treatment as usual, with mean difference (on 0 to 100 scale) of ‐5.61 (95% CI ‐17.25 to 6.02). Both trials were assessed as at high risk of bias.

Analysis 5.1.

Comparison 5 therapist versus control, Outcome 1 Average pain score.

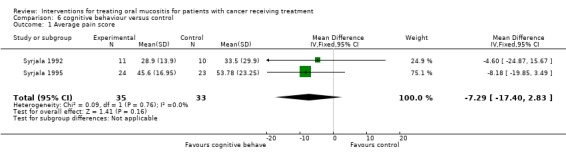

Cognitive behaviour therapy versus control

Two trials (Syrjala 1992; Syrjala 1995) provided data (Analysis 6.1) for average pain score and the meta analysis showed no statistically significant difference between the group who received cognitive behaviour therapy and those who received treatment as usual (control group) with mean difference (on 0 to 100 scale) of ‐7.29 (95% CI ‐17.40 to 2.83). Both trials were assessed as at high risk of bias.

Analysis 6.1.

Comparison 6 cognitive behaviour versus control, Outcome 1 Average pain score.

Discussion

Oral mucositis is a common and painful complication of cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. It can limit the tolerability of therapy, leading to reductions in treatment and, therefore, potentially limiting treatment efficacy (Kowanko 1998). This review updates the evidence for the efficacy of interventions to treat mucositis and another Cochrane review looks at the evidence for preventing mucositis (Worthington 2007b).

Since our original reviews there has been an expansion of evidence in this area of cancer care. The number and range of interventions have increased. In addition, the last 5 years have seen increasingly frequent reporting of outcomes other than the presence or absence of mucositis. As a result, two new outcomes were included in our previous update (2005) of this review: time taken to heal mucositis and duration of pain control therapy. Our current update includes a further outcome: the severity of mucositis. To reflect the increased number and range of studies the review has been split into two parts, one evaluating the effectiveness of agents to treat mucositis and the other the management of pain associated with the condition. There has been increasing recognition that other endpoints, such as oral intake (ability to take fluids or solid food by mouth), quality of life and duration of hospital stay, may be clinically more relevant and more important to patients (Bellm 2002). Unfortunately, there was insufficient data to include these more patient‐oriented endpoints in this review nor was there data on systemic infection and use of antibiotics. Whilst this latter outcome is often cited as a possible consequence of mucositis it may be due to other causes.

The broad scope of interventions included in this review indicate the importance of this condition to clinicians and the uncertainty of how to manage it optimally. The 32 trials included have recruited 1505 patients and evaluated 27 different interventions. Of all the interventions examined in this review only three mucositis treatments were investigated by more than one trial and only one comparison was significant for one outcome: low level laser treatment was found to reduce the severity of mucositis. There were only three comparisons for pain control which included more than one trial, only one of which showed a statistically significant effect. There was no evidence to suggest that there was a difference in pain control between continuous infusion and patient controlled analgesia (PCA). However, the PCA group required less morphine than the continuous infusion group, and the pain lasted for 2 days less.

For the remainder of the comparisons of treatment and pain control examined in this review, a lack of duplication of studies by independent groups investigating the same interventions limits the strength of evidence and generalisability of the results. Our review agrees with two systematic reviews looking at antimicrobial therapy (Donnelly 2003) and GM‐CSF (Fung 2002) for the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis. There is no clear pattern emerging regarding the benefit or otherwise of antimicrobial use to manage mucositis. Studies looking at GM‐CSF are limited and the use of GM‐CSF cannot currently be recommended for the treatment of mucositis.

Several issues identified in this review may have affected the validity of the results. The setting of the included trials varied with the majority being conducted by medical teams who did not report any involvement with a dentist or hygienist (68%). None of the trials assessed the reliability of the outcome measures used, particularly with regard to the presence or absence of oral candidiasis. The appearance of mucositis and oral candidiasis can be similar; leading to potential mis‐diagnosis if the assessors were not sufficiently trained or experienced in the diagnosis of these oral lesions. Several different scoring systems were used to assess mucositis severity and in some studies the scoring systems were not defined. This variability may have led to discrepancies between studies. Accepting that caveat, there was consistency in the number of categories used and in every case the lowest score indicated no mucositis. Only four of the included studies reported power calculations a priori (Genot‐Klastersky 2008; Loprinzi 1997; Masucci 2005) and one trial reported a post hoc power calculation as an explanation for their findings (Schubert 1987). It is possible that some studies which found no difference between treatments compared were underpowered. With respect to publication bias, several negative studies for mucositis have been reported and we congratulate the authors and editors for doing so. It was not possible to detect any existing publication bias, as there were insufficient studies in each meta‐analysis investigating the same interventions.

The country of conduct, financial support and the design of trials varied greatly between studies. It was especially unfortunate that six studies presented data in an unusable form. We feel that the use of structured abstracts and adherence to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines will greatly improve the reporting and hopefully the conduct of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Begg 1996; Moher 2001).

For patients being treated for cancer the decision‐making around giving potentially toxic therapy to prevent mucositis versus treating mucositis once it is established can be a clinical dilemma. Our recent review of interventions to prevent mucositis identified a small number of interventions with weak, unreliable evidence of benefit. This review of therapies for established mucositis shows limited evidence, from two small trials including a total of 57 participants, that low level laser treatment reduced mucositis severity, and unreliable evidence that opiate delivered by PCA results in a lower total dose of opiate, and improved duration of pain control compared to delivery by a continuous infusion. Given the pain and inconvenience that mucositis causes to a population of patients receiving treatment for cancer it is important that further, well designed, RCTs should be conducted investigating new treatments for the management of mucositis and new ways of controlling pain. Future studies should include more patient‐oriented outcomes in addition to measures of mucositis severity.

Authors' conclusions

There is limited evidence that low level laser treatment is beneficial in reducing the severity of mucositis. There is no evidence that patient controlled analgesia is better than continuous infusion method for controlling pain. However there is unreliable evidence that less opiate is used per hour, and the duration of pain is slightly reduced with patient controlled analgesia.

There is a need for further, well designed trials, preferably including a placebo or no treatment control, assessing the effectiveness of interventions considered in this review and new interventions for managing oral mucositis. These should be reported according to the CONSORT guidelines. Consideration should be given to the adoption of standard clinical outcome measures, the development of patient based outcome measures and inclusion of the cost of the interventions.

Feedback

Low level laser, 9 August 2010

Summary

"I ask you to file and publish the following comment:

There seems to be an imbalance in the way that low level laser therapy (LLLT) is handled in the risk of bias assessment and the review conclusion. The two LLLT‐studies receive the highest method scores of the review with 7/7 and 6/7 points, respectively, and no red circles for high bias risk in the assessments. Still in the results section, the Kuhn (6/7) LLLT study is classified as having high risk of bias. Although the scientific evidence may be classified as limited for LLLT in oral mucositis, I cannot see that the published conclusion of weak and unreliable evidence is justified for studies receiving such extraordinarily high method scores. Another matter is that the review only includes less than half of the published LLLT trials in cancer therapy‐induced oral mucositis."

Reply

The Kuhn 2009 study was correctly assessed as being at unclear risk of bias under the heading Effects of Interventions‐ Laser versus sham treatment, but was not included in the group at unclear risk of bias, under the heading Risk of Bias. This error has been corrected.

We have amended the text in the Abstract, Results & Discussion sections concerning low level laser therapy, deleting the word unreliable and describing the evidence as limited. The term 'unreliable' has been added to the description of the evidence for patient controlled analgesia as these trials are at either unclear or high risk of bias.

We believe that we have included all of the trials of low level laser therapy for the treatment of oral mucositis that meet the inclusion criteria for this review. An update of a second systematic review of interventions for the prevention of oral mucositis is nearing completion and is due to be published later this year. We would be grateful if Professor Bjordal could send us information about other trials that he believes should be included in these review(s).

We would like to thank Professor Bjordal for taking the time to bring these matters to our attention.

Contributors

Professor Jan Bjordal, Centre for Evidence‐based Practice, Bergen University College, Norway

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to Anne Littlewood, Trials Search Co‐ordinator for the Cochrane Oral Health Group for carrying out the searches for the review, Luisa Fernandez Mauleffinch, Managing Editor of the Cochrane Oral Health Group for her help with the administration of the review and Phil Riley for his help in locating all the articles for the review. Thanks also go to Tim Eden (OE) who provided advice on cancer, its treatment and the interventions included in past versions of the review. Thanks also go to Tatiana Macfarlane, Marco Esposito, Mikako Hayashi and Angelika Schreiber for translating papers from Russian, Italian, Japanese and German. The review authors would like to thank the following trialists for responding to letters requesting information: Dr Giuseppe Masucci, Dr MUR Naidu, Dr Charles Loprinzi, Dr Richard Chapman, Dr Ruby Meredith, Dr Richard Clark, Professor Michael Hejna, Dr Anna Sureda, Professor Marylin Dodd. Finally the review authors are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their very helpful comments which greatly improved this update of the review: Douglas Peterson, Alexander Molassiotis, Marco Esposito, Ian Needleman, David Moles, Lee Hooper, Marylin Dodd, Amid Ismail and Anne‐Marie Glenny.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Oral Health Group's Trials Register; Cochrane Pain, Palliative & Supportive Care Group's Trials Register search strategy

((neoplasm* OR leukemia OR leukaemia OR leukaemia OR lymphoma* OR plasmacytoma OR "histiocytosis malignant" OR reticuloendotheliosis OR "sarcoma mast cell" OR "Letterer Siwe disease" OR "immunoproliferative small intestine disease" OR "Hodgkin disease" OR "histiocytosis malignant" OR "bone marrow transplant*" OR cancer* Or tumor* OR tumour* OR malignan* OR neutropeni* OR carcino* OR adenocarcinoma* OR radioth* OR radiat* OR radiochemo* OR irradiat* OR chemo*) AND (stomatitis OR "Stevens Johnson syndrome" OR "candidiasis oral" OR mucositis OR (oral AND (cand* OR mucos* OR fung*)) OR mycosis OR mycotic OR thrush))

Appendix 2. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials (CENTRAL) search strategy

Search strategy for the Cochrane Library

Exp NEOPLASMS

Exp LEUKEMIA

Exp LYMPHOMA

Exp RADIOTHERAPY

Exp BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION

neoplasm* or cancer* or carcino* or malignan*

leukemi* or leukaemia*

tumour* or tumor*

neutropeni*

adenocarcinoma*

lymphoma*

(radioth* or radiat* or irradiat* or radiochemo*)

(bone next marrow next transplant*)

chemo* or radiochemo*

(#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14)

Exp STOMATITIS

MUCOSITIS

CANDIDIASIS ORAL

stomatitis

(stevens next johnson next syndrome)

mucositis

oral near cand*

mouth near cand*

oral and fung*

mouth and fung*

(mycosis or mycotic or thrush)

#16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26

#15 AND #27

Appendix 3. MEDLINE via OVID search strategy (including MEDLINE Pre‐Indexed)

1. exp NEOPLASMS/ 2. exp LEUKEMIA/ 3. exp LYMPHOMA/ 4. exp RADIOTHERAPY/ 5. Bone Marrow Transplantation/ 6. neoplasm$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 7. cancer$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 8. (leukaemi$ or leukemi$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 9. (tumour$ or tumor$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 10. malignan$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 11. neutropeni$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 12. carcino$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 13. adenocarcinoma$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 14. lymphoma$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 15. (radioth$ or radiat$ or irradiat$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 16. (bone adj marrow adj5 transplant$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 17. chemo$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 18. or/1‐17 19. exp STOMATITIS/ 20. Candidiasis, Oral/ 21. stomatitis.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 22. mucositis.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 23. (oral and cand$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 24. (oral adj6 mucos$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 25. (oral and fung$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 26. (mycosis or mycotic).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, device trade name] 27. or/19‐26 28. 18 and 27

The above subject search was run with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity maximising version (September 2009 revision) as referenced in Chapter 6 and detailed in box 6.4.c of The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009].

1. randomized controlled trial.pt.

2. controlled clinical trial.pt.

3. randomized.ab.

4. placebo.ab.

5. drug therapy.fs.

6. randomly.ab.

7. trial.ab.

8. groups.ab.

9. or/1‐8

10. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

11. 9 not 10

Appendix 4. EMBASE via OVID search strategy

1. exp NEOPLASM/ 2. exp LEUKEMIA/ 3. exp LYMPHOMA/ 4. exp RADIOTHERAPY/ 5. exp bone marrow transplantation/ 6. (neoplasm$ or cancer$ or leukemi$ or leukaemi$ or tumour$ or tumor$ or malignan$ or neutropeni$ or carcino$ or adenocarcinoma$ or lymphoma$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] 7. (radioth$ or radiat$ or irradiat$ or radiochemo$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] 8. (bone marrow adj3 transplant$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] 9. chemo$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] 10. or/1‐9 11. exp Stomatitis/ 12. Thrush/ 13. (stomatitis or mucositis or (oral and candid$) or (oral adj4 mucositis) or (oral and fung$) or mycosis or mycotic or thrush).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] 14. or/11‐13 15. 10 and 14

The above subject search was run with the Cochrane Oral Health Group sensitive search strategy for identifying randomized controlled trials in EMBASE:

1. random$.ti,ab. 2. factorial$.ti,ab. 3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).ti,ab. 4. placebo$.ti,ab. 5. (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 6. (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 7. assign$.ti,ab. 8. allocat$.ti,ab. 9. volunteer$.ti,ab. 10. CROSSOVER PROCEDURE.sh. 11. DOUBLE‐BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 12. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.sh. 13. SINGLE BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 14. or/1‐13 15. ANIMAL/ or NONHUMAN/ or ANIMAL EXPERIMENT/ 16. HUMAN/ 17. 16 and 15 18. 15 not 17 19. 14 not 18

Appendix 5. CINAHLvia EBSCO search strategy

S1 (MH "Neoplasms+")

S2 (MH "Leukemia+")

S3 (MH "Lymphoma+")

S4 (MH "Radiotherapy+")

S5 (MH "Bone Marrow Transplantation")

S6 neoplasm*

S7 cancer*

S8 (leukemi* or leukaemi*)

S9 (tumour* or tumor*)

S10 malignan*

S11 neutropeni*

S12 carcino*

S13 adenocarcinoma*

S14 lymphoma*

S15 (radioth* or radiat* or irradiat*)

S16 (bone N1 marrow N5 transplant*)

S17 chemo*

S18 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or

S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17

S19 MH "Stomatitis+"

S20 MH "Candidiasis, Oral"

S21 stomatitis

S22 mucositis

S23 (oral and cand*)

S24 (oral N6 mucos*)

S25 (oral and fung*)

S26 (mycosis or mycotic)

S27 S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26

S28 S18 AND S27

The above subject search was run with the Cochrane Oral Health Group sensitive search strategy for identifying randomized controlled trials in CINAHL:

S1 MH Random Assignment or MH Single‐blind Studies or MH Double‐blind Studies or MH Triple‐blind Studies or MH Crossover design or MH Factorial Design

S2 TI ("multicentre study" or "multicenter study" or "multi‐centre study" or "multi‐center study") or AB ("multicentre study" or "multicenter study" or "multi‐centre study" or "multi‐center study") or SU ("multicentre study" or "multicenter study" or "multi‐centre study" or "multi‐center study")

S3 TI random* or AB random*

S4 AB "latin square" or TI "latin square"

S5 TI (crossover or cross‐over) or AB (crossover or cross‐over) or SU (crossover or cross‐over)

S6 MH Placebos

S7 AB (singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) or TI (singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*)

S8 TI blind* or AB mask* or AB blind* or TI mask*

S9 S7 and S8

S10 TI Placebo* or AB Placebo* or SU Placebo*

S11 MH Clinical Trials

S12 TI (Clinical AND Trial) or AB (Clinical AND Trial) or SU (Clinical AND Trial)

S13 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12

Appendix 6. CANCERLIT (PubMed Cancer Subset) search strategy

((neoplasm* OR leukemia OR leukaemia OR leukaemia OR lymphoma* OR plasmacytoma OR "histiocytosis malignant" OR reticuloendotheliosis OR "sarcoma mast cell" OR "Letterer Siwe disease" OR "immunoproliferative small intestine disease" OR "Hodgkin disease" OR "histiocytosis malignant" OR "bone marrow transplant*" OR cancer* Or tumor* OR tumour* OR malignan* OR neutropeni* OR carcino* OR adenocarcinoma* OR radioth* OR radiat* OR radiochemo* OR irradiat* OR chemotherap*) AND (stomatitis OR "Stevens Johnson syndrome" OR "candidiasis oral" OR mucositis OR (oral AND (candid* OR mucos* OR fung*)) OR mycosis OR mycotic OR thrush))

The above subject search was run with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity maximising version (September 2009 revision) as referenced in Chapter 6 and detailed in box 6.4.a of The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009]

#1 randomized controlled trial [pt] #2 controlled clinical trial [pt] #3 randomized [tiab] #4 placebo [tiab] #5 drug therapy [sh] #6 randomly [tiab] #7 trial [tiab] #8 groups [tiab] #9 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 #10 animals [mh] NOT humans [mh] #11 #9 NOT #10

Appendix 7. OpenSIGLE search strategy

SIGLE no longer supports complex searching, so a series of keyword searches was performed as below:

cancer AND mucositis AND oral

leukemia AND mucositis AND oral

leukaemia AND mucositis AND oral

carcinoma AND mucositis AND oral

lymphoma AND mucositis AND oral

tumour AND mucositis AND oral

tumor AND mucositis AND oral

cancer AND candidiasis AND oral

leukemia AND candidiasis AND oral

leukaemia AND candidiasis AND oral

carcinoma AND candidiasis AND oral

lymphoma AND candidiasis AND oral

tumour AND candidiasis AND oral

tumor AND candidiasis AND oral

Appendix 8. LILACS via the Virtual Health Library search strategy

Mh NEOPLASMS OR Tw neoplasm$ OR Tw cancer$ OR Tw carcinoma$ OR Tw tumour$ OR Tw tumor$ OR Tw malignan$ OR Tw carcino$ OR Tw nuetropeni$ OR Tw adenocarcinoma$ OR Mh leukemia OR Tw leukaemia$ OR Tw leukemi$ OR Tw lymphoma$ OR Tw "bone marrow transplantation" OR Tw "bone marrow transplant$" OR Tw radiotherapy OR Tw radioth$ OR Tw radiat$ OR Tw irradiat$ OR Tw radiochemo$ OR Tw chemo$

AND

Mh stomatitis OR Tw stomatitis OR Mh Candidiasis‐Oral OR Tw "oral candidiasis" OR (Tw candida$ AND (Tw mouth OR Tw oral)) OR Tw mucositis OR ((Tw oral OR mouth) AND Tw fung$) OR (Tw oral AND Tw candidiasis$)

The above subject search was run with the Brazilian Cochrane Centre highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomized controlled trials in LILACS:

((Pt randomized controlled trial OR Pt controlled clinical trial OR Mh randomized controlled trials OR Mh random allocation OR Mh double‐blind method OR Mh single‐blind method) AND NOT (Ct animals AND NOT (Ct human and Ct animal)) OR (Pt clinical trial OR Ex E05.318.760.535$ OR (Tw clin$ AND (Tw trial$ OR Tw ensa$ OR Tw estud$ OR Tw experim$ OR Tw investiga$)) OR ((Tw singl$ OR Tw simple$ OR Tw doubl$ OR Tw doble$ OR Tw duplo$ OR Tw trebl$ OR Tw trip$) AND (Tw blind$ OR Tw cego$ OR Tw ciego$ OR Tw mask$ OR Tw mascar$)) OR Mh placebos OR Tw placebo$ OR (Tw random$ OR Tw randon$ OR Tw casual$ OR Tw acaso$ OR Tw azar OR Tw aleator$) OR Mh research design) AND NOT (Ct animals AND NOT (Ct human and Ct animals)) OR (Ct comparative study OR Ex E05.337$ OR Mh follow‐up studies OR Mh prospective studies OR Tw control$ OR Tw prospectiv$ OR Tw volunt$ OR Tw volunteer$) AND NOT (Ct animals AND NOT (Ct human and Ct animals)))

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

benzydamine mouthwash versus placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement in mucositis | 2 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.94, 1.60] |

Comparison 2.

low level laser versus sham

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mild to moderate mucositis | 2 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.28 [2.30, 12.13] |

Comparison 3.

sucralfate versus placebo/salt and water/salt and soda

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mucostis eradicated | 2 | 84 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.66, 1.94] |

Comparison 4.

morphine (PCA) versus morphine (CI)

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Average pain score | 3 | 113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.49 [‐12.28, 7.29] |

| 2 Daily mean opiate intake per hour | 3 | 113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.65 [‐1.20, ‐0.09] |

| 3 Duration of pain control | 3 | 113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.87 [‐3.49, ‐0.25] |

Comparison 5.

therapist versus control

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Average pain score | 2 | 69 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.61 [‐17.25, 6.02] |

Comparison 6.

cognitive behaviour versus control

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Average pain score | 2 | 68 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐7.29 [‐17.40, 2.83] |

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 August 2010 | Feedback has been incorporated | Error concerning overall risk of bias categorisation for Kuhn 2009 corrected. Wording changed in results and discussion sections concerning low level laser treatment, in response to feedback received. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2000 Review first published: Issue 1, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 July 2010 | New search has been performed | New searches up to 01 June 2010. |

| 6 July 2010 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | 5 new included studies, 8 new excluded studies. Risk of bias assessments completed on all included studies. Added new outcome: proportion of patients with mild/moderate mucositis. Review restructured to reflect many of comparisons have only one trial and to downgrade this. 4 new authors. |

| 17 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 16 February 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. In this update we have added 1 included and 28 excluded studies. |

Differences between protocol and review

New outcome added for 2010 update: proportion of patients with severe mucositis.

Two new outcomes added for 2005 update: time taken to heal mucositis; duration of pain control therapy.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Location: Iran. Number of centres: Multicentre. Funding source: Unclear. Recruitment period: December 2006 to May 2007. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion: Adults undergoing chemotherapy who developed oral mucositis Gr 2 or worse, with no other systemic disease, life expectancy at least 6 months. Exclusion: Other concomitant disease, heavy smoker, severe psychological disorder. 14 randomised, 12 completed. |

|

| Interventions | GpA (6) Phenytoin, 0.5% (50:50 mixture sodium phenytoin and phenytoin powder), 10 ml given 4 times daily, swished around mouth and spat out. GpB (6) Placebo 10 ml 4 times daily, swished around mouth and spat out. |

|

| Outcomes | Assessed at baseline, 1 week and 2 weeks after start of treatment. VAS scores for pain, Mucositis score NCI Common Toxicity Criteria (0 to 4 scale), duration of mucositis (not used as data presented in a format not suitable for pooling). |

|

| Notes | No power calculation reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | 'Patients were assigned to case and control groups randomly and separately at each department. Sampling method was performed on a multi‐central, non‐probable (easy to access) basis.' |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not mentioned. |

| Blinding of participants/carers? | Low risk | Patients and nurses blinded to treatment group. |

| Blinding of outcome assessors? | Unclear risk | Ppatients self assessed pain and QoL, unclear who conducted the mucositis assessments. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? | Unclear risk | 2/14 randomised were subsequently excluded because they were 'uncooperative' ‐ no details given. It is not stated which group these were from, but if both exclusions were from the same group, this would represent 25% drop out from that group and a significant risk of bias. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | Reported mucositis scores, duration of mucositis, pain and quality of life. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

| Methods | Location: United Kingdom. Number of centres: Two. Funding source: Not stated. Recruitment period: September 2004 to April 2005. |

|

| Participants | Adults aged 18 years and over, with at least Grade 1 OM and when they felt they were no longer receiving adequate pain control via simple analgesic, receiving daily doses of radiotherapy to the head and neck. 20 eligible, 20 randomised. |

|

| Interventions | GpA (10) Gelclair, 4x in the 24 hour study (30 min to 1 hour before eating/drinking and before bedtime, swished around mouth and spat out). GpB (10) Standard care 10 ml 4x in 24 hour study (30 min to 1 hour before eating/drinking sucralfate and Mucaine swished around mouth and swallowed) (30 min to 1 hour before eating/drinking). |

|

| Outcomes | Assessed at baseline, 1 hour, 3 hours and 24 hours post treatment. VAS scores for pain (not used as only 24 hour assessment), Pain on speaking, Mucositis score NCI Common Toxicity Criteria (0‐4 scale). Secondary outcome ‐ extent to which ability to swallow is influenced by pain (odynophagia). |

|

| Notes | Outcomes assessed by nurse specialists blinded to group allocation. No power calculation reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: "computer generated random allocation sequence for the 2 centres was prepared by Exeter clinical research radiographer". |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Quote: "radiographer accessed the randomisation list by telephone to determine the patients group allocation". |