Abstract

Huntington disease (HD) is a disorder characterized by chorea, dystonia, bradykinesia, cognitive decline and psychiatric comorbidities. Balance and gait impairments, as well as falls, are common manifestations of the disease. The importance of compensatory rapid stepping to maintain equilibrium in older adults is established, yet little is known of the role of stepping response times (SRTs) in balance control in people with HD. SRTs and commonly-used clinical measures of balance and mobility were evaluated in fourteen symptomatic participants with HD, and nine controls at a university mobility research laboratory. Relative and absolute reliability, as well as minimal detectable change in SRT were quantified in the HD participants. HD participants exhibited slower SRTs and poorer dynamic balance, mobility and motor performance than controls. HD participants also reported lower balance confidence than controls. Deficits in SRT were associated with low balance confidence and impairments on clinical measures of balance, mobility, and motor performance in HD participants. Measures of relative and absolute reliability indicate that SRT is reliable and reproducible across trials in people with HD. A moderately low percent minimal detectable change suggests that SRT appears sensitive to detecting real change in people with HD. SRT is impaired in people with HD and may be a valid and objective marker of disease progression.

Keywords: Stepping response time, balance, mobility, Huntington disease

1. Introduction

Huntington disease (HD) is a phenotypically heterogeneous disease characterized by choreiform and dystonic movements [1], bradykinesia [2–3], cognitive decline [4], and psychiatric comorbidities [5]. Balance and gait impairments [6–7], recurrent falls [8–9], and functional decline and disability [10] are common manifestations of the disease. The frequency of recurrent falls (≥2 annually), which significantly contributes to morbidity and mortality, is as high as 58–60% [8–9], suggesting that balance is a significant problem in people with HD. Numerous measures including excessive medio-lateral trunk sway during gait, shorter stride length, greater stride variability, slower gait velocity, lower balance confidence, lower walking activity, and poorer performance on clinical balance and mobility tests such as the Berg Balance Scale [11] and Timed Up and Go (TUG) [12], are associated with recurrent falls in people with HD [8–9].

Muscle activation patterns in the form of ankle and hip strategies are important in countering perturbations threatening control of equilibrium. Although motion about the ankle and hip joints move the body’s center of mass (CoM) over the base of support (BoS) to restore equilibrium [13], the execution of a compensatory step may be required to rapidly alter the BoS to restore stability during challenges to equilibrium in daily activities [14]. Investigations have shown declines in the ability to execute a rapid step to regain balance after being released from a forward leaning position in older adults [15], as well as significantly increased stepping reaction times in older adult fallers [16]. Furthermore, falls risk measures such as poor single leg stance time and low balance confidence correlate with poorer performance on a rapid stepping test in older adults [17]. These studies highlight the importance of rapid stepping as a measure of falls risk in older adults. Given the importance of rapid stepping capabilities in balance function in older adults, coupled with the high rate of falls in people with HD, we evaluated stepping response time (SRT) and clinical measures of balance, mobility and motor performance in symptomatic participants with HD and controls. In the participants with HD, we also evaluated associations between SRT and clinical measures of balance, mobility and motor performance commonly assessed in HD mobility studies [6, 18]. We hypothesized that SRT would be slower in participants with HD than in controls, and that slower SRT would be associated with lower balance confidence [19], and poorer performance on the TUG [12], functional reach (FR) [20], and Unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) motor items which assess gait and balance function in people with HD [21]. We also quantified relative and absolute reliability, as well as minimal detectable change (MDC) in SRT in participants with HD. The MDC is the minimum amount of change in a variable not likely to be due to chance variation in measurement [22], and in clinical studies is considered to represent real change in performance beyond measurement error [23]. Knowledge of minimal change values of performance measures such as SRT may be useful in assessing disease progression as well as response to clinical interventions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

Fourteen symptomatic participants with HD attending the Neurogenetics Clinic at the Detroit Medical Center participated in this study. Participants were included if they had expanded CAG repeats on genetic testing, clinical signs of HD assessed by a neurologist, were ambulatory but exhibited deficits on at least two out of the three of the gait, tandem walking, or retropulsion items of the motor section of the UHDRS, had no other history of neurological disease that might affect balance, were stable as established by medical history (e.g., no acute cardiopulmonary, infectious or inflammatory conditions) and therefore able to tolerate the testing procedures, and were able to provide informed consent to participate in the study. As chorea and dystonia are not major determinants of disability [1], only participants with HD who exhibited signs of voluntary movement impairments in the UHDRS motor items tested (gait, tandem walking, or retropulsion) were included in this analysis, irrespective of presence or absence of chorea and dystonia. Nine individuals served as controls, none of whom had genetic testing for HD. They were included if they denied a positive family history of the disease, had no history of neurological disease that might affect balance, were medically stable and could tolerate the testing procedures, and tested normal on the gait, tandem walking, and retropulsion items of the motor section of the UHDRS. The Human Investigation Committee of Wayne State University approved the study protocol, and all participants consented to participate in the study.

2.2 Stepping Response Time

Standing with the foot of the dominant leg on a foot-pad, participants reacted to an auditory stimulus by stepping as rapidly as possible onto a second foot-pad eighteen inches away. All trials were conducted for a single leg only. A low tone acted as a preparatory cue, and the changing of the tone to a high tone represented the stimulus to execute a rapid step. The cuing phase was variable in length to avoid anticipation. The foot-pads were connected to a Multi-Operational Apparatus for Reaction Time (MOART) device (Lafayette Instruments), which downloaded reaction and movement times (milliseconds, ms) to an attached computer in real time. Participants were given a number of practice trials to become familiar with the procedure and to ensure that responses were stable. Participants performed three experimental stepping trials, each of which assessed reaction time (time taken from receipt of the stimulus to lifting the stepping foot off of the foot-pad), and movement time (time from lifting the stepping foot off of the foot-pad to planting the stepping foot on the second foot-pad eighteen inches away). SRT was computed as the sum of reaction time plus movement time for each stepping trial. The mean of the three trials was recorded as the SRT for each participant.

2.3 Clinical measures of balance, mobility and motor performance

2.3.1 Unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS)

The UHDRS is a commonly-used clinical assessment tool of motor, cognitive, and behavioral function in HD [21]. The gait, tandem walk, and retropulsion items from the UHDRS motor scale were administered to all participants. The gait test assessed quality of gait including size of the base, speed, difficulty ambulating, and assistance needed. Tandem walking was an assessment of the number of deviations observed during ten steps of heel-toe walking. Retropulsion was a pull test at the shoulders to assess recovery from posterior displacement with the participant in standing. Each item was scored on a five-point ordinal scale from 0 (normal; no disability) to 4 (cannot perform; maximum disability), for a total possible UHDRS motor score of twelve.

2.3.2. Balance confidence

The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale [19] is a measure of balance confidence in which individuals verbally rate their confidence on a scale of 0% (not confident) to 100% (completely confident) in performing a series of sixteen balance-challenging tasks of daily living. Balance confidence was scored as the mean of the sixteen responses and reported as a percentage. Balance confidence is low in recurrent fallers with HD (48.9%) [9].

2.3.3 Timed Up and Go

TUG is a reliable measure of dynamic balance and functional mobility [12]. TUG is the time taken to rise up from the seated position, walk three meters at “comfortable and safe” walking speed, turn around, walk three meters to return to the seated position. A practice trial preceded two experimental trials, the mean of which was the TUG score. In a study of mobility and balance impairments in HD, TUG correlated with quantitative gait measures such as gait speed, as well as with dynamic balance and falls, and is a valid test of mobility and dynamic balance in people with the disease [6]. TUG scores ≥14s are associated with an increased risk for recurrent falls in people with HD [9].

2.3.4. Functional Reach

FR is a reliable measure of anticipatory balance control and margin of stability [20]. FR is the maximum distance one can reach forward beyond arm’s length while maintaining a fixed base of support in standing, and is measured with a yardstick affixed to the wall at the level of the acromion. A practice trial preceded two experimental trials, the mean of which was the FR score. FR correlates with dynamic balance measures, and is a valid test of balance in people with the disease [6].

2.4 Statistical analyses

Differences between HD participants and controls were assessed using independent samples t-tests in the case of normally distributed continuous variables (age, height, weight, body mass index, ABC scale, TUG, and FR), Fisher’s Exact Test in the case of categorical variables (gender), and the Mann-Whitney U test in the case of UHDRS, an ordinal variable. Differences between groups for SRT were evaluated using independent samples t-tests and univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with age and body mass index as covariates. Associations between SRT and clinical measures of balance, mobility and motor performance were assessed for the participants with HD using Pearson’s correlation coefficient or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Relative reliability of SRT was assessed for the participants with HD using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC3,1) [24]. The standard error of measurement (SEM), a statistic which quantifies measurement error in the same units as the original measurement [25], was used to quantify absolute reliability of SRT in the participants with HD. The SEM of SRT was computed as SD(1-ICC3,1)1/2 [26], where SD was the standard deviation of mean SRT, and ICC3,1 the relative reliability coefficient for SRT. The MDC of SRT at the 95% confidence level (MDC95) was computed in the participants with HD as z*SEM*√2 [25] using a value of 1.96 as the z-score associated with the 95% confidence interval. Significance was set at p< 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Participant characteristics and clinical measures

Characteristics of the HD and control participants are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, height, weight, body mass index, or gender between the groups (p= 0.18–0.95), although HD participants tended to be slightly older and have a lower body mass index than controls. Twelve of the HD participants had a positive family history, with two participants reporting an unknown family history of HD. Clinical measures for the HD and control participants are presented in Table 1. The HD participants had a mean CAG length of 46.9 repeats (range 40–66 repeats), and consistent with other studies [27], longer CAG repeat length was strongly associated with earlier age of onset of symptoms (Pearson’s r=.−.81; p=0.001). The mean duration of disease symptoms was approximately 5.6 years (range 1.0–8.5 years), and mean age of onset of symptoms was 40.9 (range 22.7–53.8 years). The HD participants had significantly higher scores on each of the components of the motor UHDRS tested (gait; tandem walk, and retropulsion) (all p<0.001), indicating poorer motor performance than controls. The ABC score was significantly lower in the HD participants (p=0.001), with the score of 56.8% indicating low levels of balance confidence during performance of daily activities. TUG score was significantly higher in HD participants (p=0.001), indicating poorer dynamic balance and functional mobility than controls. However, the mean TUG score of 11.2 seconds in HD participants was below 14 seconds, the score shown to increase risk for recurrent falls in people with HD [9]. FR scores were similar across the groups (p=0.30). The mean FR score of 13.2 inches in HD participants suggests good anticipatory balance control and margin of stability.

Table 1.

Characteristics and clinical measures of participants with Huntington disease (HD) and controls (CON).

| HD (n=14) | CON (n=9) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | ||

| Characteristic | |||

| Age (y) | 46.5 (9.1) | 40.8 (12.1) | 0.21 |

| Height (m) | 1.72 (0.1) | 1.72 (0.1) | 0.95 |

| Weight (kg) | 67.9 (12.0) | 77.8 (20.1) | 0.21 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.0 (3.6) | 26.3 (6.2) | 0.18 |

| Sex, female (%) | 42.9 | 66.7 | 0.40 |

| Clinical measures | |||

| Number of CAG repeats | 46.9 (6.5) | NT | - |

| Age of onset of symptoms (y) | 40.9 (9.9) | - | - |

| UHDRS (motor) | 3.8 (1.8) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Gait | 0.9 (0.6) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Tandem walk | 1.7 (0.9) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Retropulsion | 1.2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Balance confidence (%) | 56.8 (32.9) | 95.1 (5.6) | 0.001 |

| Timed up and go (s) | 11.2 (2.2) | 8.6 (1.1) | 0.001 |

| Functional reach (in) | 13.2 (2.2) | 14.4 (2.9) | 0.30 |

Note: UHDRS; Unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale. UHDRS (motor) is the sum of the gait, tandem walk, and retropulsion items (see Methods for scoring). NT; not tested.

3.2 Stepping response time

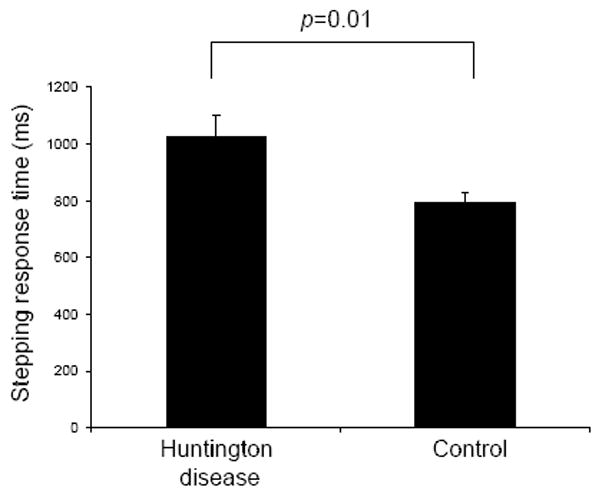

SRT was significantly slower in HD participants than in controls (p=0.01) (Figure 1). Univariate ANCOVA controlling for differences in age and body mass index between the groups confirmed that SRT was slower in HD participants (p=0.03).

Figure 1.

Stepping response times for participants with Huntington disease (HD) and controls. Response time was significantly slower in the HD participants than in controls (p=0.01). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Correlations between SRT and clinical measures of balance, mobility and motor performance are presented in Table 2 for the HD participants. The correlation between ABC score and SRT (Pearson’s r=−0.67; p<0.01), suggests that slower SRT was associated with lower balance confidence. Slower SRT was associated with poorer performance on the TUG (Pearson’s r=0.57; p=0.03), and on the UHDRS tandem walk test (Spearman’s rho=0.58; p=0.03). The relationship between SRT and FR was fair (Pearson’s r=−0.44; p=0.11). These correlations suggest that deficits in SRT are associated with impairments in clinical balance, mobility and motor performance in people with HD.

Table 2.

Association between SRT and clinical measures of balance, mobility and motor performance in participants with Huntington disease (n=14).

| Correlation coefficient | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical measures | ||

| UHDRS (motor) | 0.46 | 0.10 |

| Gait | 0.27 | 0.35 |

| Tandem walk | 0.58 | 0.03 |

| Retropulsion | 0.13 | 0.67 |

| Balance confidence | −0.67 | <0.01 |

| Timed up and go | 0.57 | 0.03 |

| Functional reach | −0.44 | 0.11 |

3.3 Reliability and minimal detectable change

Relative and absolute reliability, as well as minimal detectable change in SRT were quantified in the HD participants. Relative reliability of SRT was excellent (ICC3,1=0.90). Absolute reliability of SRT assessed as SEM was 87.3 ms. The SEM%, SEM expressed as a percentage of mean SRT was 8.5%, suggesting low measurement error and excellent absolute reliability of SRT. The MDC95 value for SRT was 241.8 ms, and the MDC95%, minimal change expressed as a percentage of mean SRT, was moderately low (23.6%), suggesting that SRT appears sensitive to detecting real change in stepping performance in people with HD.

4. Discussion

Given the important role of rapid stepping in balance control in older adults [14–17], coupled with the observation of falls rates as high as 58–60% in people with HD [8–9], we investigated SRT in participants with HD and controls. Our results showing slower SRT in HD participants extend those of others reporting slowed gait [7], prolonged reaction time [28] and slowed movement time of the upper extremity [2, 28], and longer reaction time and reduction in speed of the first step of ambulation [29] in people with HD, and are consistent with bradykinesia as an integral feature of the disease phenotype [2–3].

In this investigation we showed that deficits in SRT were associated with impairments on clinical measures of balance, mobility, and motor performance including a subjective measure related to balance—balance confidence—in HD participants. The strongest correlation (r=−0.67) was between SRT and ABC score [19], suggesting that in people with HD, slower response times are associated with lower balance confidence during performance of common daily activities. Good correlations were found between SRT and clinical measures such as TUG [12] (Pearson’s r=0.57) and tandem walk (Spearman’s rho=0.58), highlighting associations between SRT and gait-related performance measures. Slower SRT was associated with poorer performance on the TUG and the tandem walk test. These associations, together with the observation that gait (hazard ratio 3.004) and tandem walk (hazard ratio 2.546) capabilities are strong predictors of nursing home placement [10], suggest that SRT may be a valid and objective marker of disease progression. In this regard, the relationship between SRT and TUG is particularly important, as loss of independent ambulation is the primary predictor of admission to a nursing home in people with HD [10]. The clinical balance measure incorporating a static base of support, FR [20], showed a fair relationship (r=−0.44) with SRT. Overall these correlations suggest that deficits in SRT are associated with lower balance confidence, and impaired dynamic balance, functional mobility and motor performance in people with HD. Deficits in SRT appear to display less of an association with balance measures in which the lower extremities remain static.

The ICC3,1 [24] was 0.90 for SRT in the HD participants. Values above 0.75 are indicative of good reliability, and for clinical measures reliability should exceed 0.90 to ensure reasonable validity [26]. The SEM%, commonly used to quantify measurement error independent of the units of measurement was 8.5% indicating low measurement error and excellent absolute reliability of SRT. The high ICC and low absolute measurement error indicate that SRT is reliable and reproducible across trials in people with HD.

In clinical studies the MDC is considered to represent real change in performance beyond that attributable to measurement error [23]. The MDC95 value computed for SRT is interpreted as meaning that 95% of people with HD whose SRT has truly remained stable, will display random variation across two consecutive trials less than or equal to 241.8 ms, and that only SRT changes exceeding 241.8 ms should be considered real change. Conversely, we can be 95% confident that change exceeding 241.8 ms is real change in SRT. The MDC95%, describes minimal change independent of the units of measurement, and enhances interpretation of the absolute MDC value in terms of sensitivity of SRT to detecting real change. The MDC95% was moderately low at 23.6%, suggesting that SRT appears sensitive to detecting real change in stepping performance in people with HD, and that a SRT change value of 241.8 ms appears realistic for some of the HD participants in this study. To the best of our knowledge this is the first quantification of a minimal change value for SRT in people with HD. Knowing what constitutes real change in SRT may be useful in assessing disease progression, as well as the efficacy of pharmacologic and rehabilitative interventions in clinical research trials. The minimal change value in SRT reported in this study should be a useful benchmark of the success of those interventions.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the HD sample in this study consisted of community-dwelling ambulatory individuals and is not representative of the broad spectrum of mobility disability observed in people with HD [6–7]. This, together with the small sample size, suggests that these results are not generalizable across the entire spectrum of HD. Second, this was a cross-sectional observational study precluding us from concluding that the deficits in SRT caused the impairments in balance and mobility observed in the HD participants. Despite these limitations, these intriguing results provide the impetus for future studies. Studies with larger sample sizes including participants with greater disability than that found in the present cohort should be undertaken to confirm the present results. As SRT is impaired in people with HD, studies are also needed to evaluate whether SRT is a valid marker of disease progression, and the extent to which SRT reflects disability in people with the disease. Randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of rehabilitative and pharmacological therapies on motor performance in HD should consider including SRT as an outcome variable to determine whether improvements in SRT, if any, are associated with improved balance, mobility and fewer falls in people with HD.

5. Conclusions

We have shown that SRT is slower, and that deficits in SRT are associated with impairments in balance and mobility in people with HD. These results suggest that SRT may be an important predictor of balance and mobility capabilities in people with HD. As SRT is impaired in people with HD and correlates with gait-related predictors of institutionalization, it may be a valid and objective marker of disease progression. Only SRT changes exceeding 241.8 ms should be considered to reflect real change in people with HD, while change less than or equal to this value should be attributed to random variation in stepping performance. Confirmation of SRT as a marker of disease progression, together with its excellent reliability, reproducibility, and low percent minimal change value, may render it a useful outcome variable and endpoint measure in clinical studies assessing the efficacy of neuroprotective agents.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their participation in this study. Dr. Stacey Schepens was supported by a National Institute of Health/National Institute on Aging Pre-Doctoral Research Training Fellowship in Aging and Urban Health to the Institute of Gerontology, Wayne State University. The financial sponsors played no role in the design, execution, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the decision to publish this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mahant N, McCusker EA, Byth K, Graham S. Huntington’s disease: clinical correlates of disability and progression. Neurology. 2003;61:1085–92. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000086373.32347.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson PD, Berardelli A, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Dick JP, Benecke R, et al. The coexistence of bradykinesia and chorea in Huntington’s disease and its implications for theories of basal ganglia control of movement. Brain. 1988;111 (Pt 2):223–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia Ruiz PJ, Hernandez J, Cantarero S, Bartolome M, Sanchez Bernardos V, Garcia de Yebenez J. Bradykinesia in Huntington’s disease. A prospective, follow-up study. J Neurol. 2002;249:437–40. doi: 10.1007/s004150200035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beglinger LJ, Duff K, Allison J, Theriault D, O’Rourke JJ, Leserman A, et al. Cognitive change in patients with Huntington disease on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2009:1–6. doi: 10.1080/13803390903313564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson KE, Gehl CR, Marder KS, Beglinger LJ, Paulsen JS. Comorbidities of obsessive and compulsive symptoms in Huntington’s disease. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:334–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181da852a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao AK, Muratori L, Louis ED, Moskowitz CB, Marder KS. Clinical measurement of mobility and balance impairments in Huntington’s disease: validity and responsiveness. Gait Posture. 2009;29:433–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao AK, Muratori L, Louis ED, Moskowitz CB, Marder KS. Spectrum of gait impairments in presymptomatic and symptomatic Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1100–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.21987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimbergen YA, Knol MJ, Bloem BR, Kremer BP, Roos RA, Munneke M. Falls and gait disturbances in Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:970–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busse ME, Wiles CM, Rosser AE. Mobility and falls in people with Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:88–90. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.147793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheelock VL, Tempkin T, Marder K, Nance M, Myers RH, Zhao H, et al. Predictors of nursing home placement in Huntington disease. Neurology. 2003;60:998–1001. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000052992.58107.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health. 1992;83 (Suppl 2):S7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horak FB, Nashner LM. Central programming of postural movements: adaptation to altered support-surface configurations. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:1369–81. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIlroy WE, Maki BE. Age-related changes in compensatory stepping in response to unpredictable perturbations. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51:M289–96. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.6.m289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thelen DG, Wojcik LA, Schultz AB, Ashton-Miller JA, Alexander NB. Age differences in using a rapid step to regain balance during a forward fall. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M8–13. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.1.m8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lord SR, Fitzpatrick RC. Choice stepping reaction time: a composite measure of falls risk in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M627–32. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.m627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medell JL, Alexander NB. A clinical measure of maximal and rapid stepping in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M429–33. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.8.m429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao AK, Louis ED, Marder KS. Clinical assessment of mobility and balance impairments in pre-symptomatic Huntington’s disease. Gait Posture. 2009;30:391–3. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell LE, Myers AM. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A:M28–34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.1.m28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan PW, Weiner DK, Chandler J, Studenski S. Functional reach: a new clinical measure of balance. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M192–7. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.m192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huntington Study Group. Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale: reliability and consistency. Mov Disord. 1996;11:136–42. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haley SM, Fragala-Pinkham MA. Interpreting change scores of tests and measures used in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2006;86:735–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollman JH, Beckman BA, Brandt RA, Merriwether EN, Williams RT, Nordrum JT. Minimum detectable change in gait velocity during acute rehabilitation following hip fracture. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2008;31:53–6. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200831020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–8. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stratford PW. Getting more from the literature: estimating the standard error of measurement from reliability studies. Physiotherapy Canada. 2004;56:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duyao M, Ambrose C, Myers R, Novelletto A, Persichetti F, Frontali M, et al. Trinucleotide repeat length instability and age of onset in Huntington’s disease. Nat Genet. 1993;4:387–92. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garnett ES, Firnau G, Nahmias C, Carbotte R, Bartolucci G. Reduced striatal glucose consumption and prolonged reaction time are early features in Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1984;65:231–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(84)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delval A, Krystkowiak P, Blatt JL, Labyt E, Bourriez JL, Dujardin K, et al. A biomechanical study of gait initiation in Huntington’s disease. Gait Posture. 2007;25:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]