SUMMARY

Children with GERD may benefit from gastric acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors such as pantoprazole. Effective treatment with pantoprazole requires correct dosing and understanding of the drug’s kinetic profile in children. The aim of these studies was to characterize the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of single and multiple doses of pantoprazole delayed-release tablets in pediatric patients with GERD aged ≥6 through 11 years (study 1) and 12 through 16 years (study 2). Patients were randomly assigned to receive pantoprazole 20 or 40 mg once daily. Plasma pantoprazole concentrations were obtained at intervals through 12 hours after the single dose, and at 2 and 4 hours after multiple doses for PK evaluation. PK parameters were derived by standard noncompartmental methods and examined as a function of both drug dose and patient age. Safety was also monitored. Pantoprazole PK was dose independent (when dose normalized) and similar toPK reported from adult studies. There was no evidence of accumulation with multiple dosing or reports of serious drug-associated adverse events. In children aged 6 to 16 years with GERD, currently available pantoprazole delayed-release tablets can be used to provide systemic exposure similar to that in adults.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal Reflux, Adolescent, Child, Pantoprazole, Pharmacokinetics, Safety

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux occurs when gastric contents pass into the esophagus1. In pediatric patients, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is present when the reflux of gastric contents is the cause of troublesome symptoms and/or complications1,2. Pharmacological treatment of GERD in pediatric patients includes acid suppression with H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)1,3. PPIs are superior to H2RAs for healing erosive esophagitis, maintaining healing, and relieving GERD symptoms1,4. PPIs have been studied in children for up to 11 years of treatment and have demonstrated a good safety profile5. Widespread empirical (off-label) use of PPIs in pediatric populations led the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to request manufacturers of PPIs to conduct a battery of studies in infants, children, and adolescents6. The FDA made this request by way of a formal Pediatric Written Request (the regulatory mechanism to implement the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act of January 1, 2004). Study design components, including diagnosis criteria, inclusion criteria, and treatment, were determined by the FDA. Details of study design in the Pediatric Written Request underwent several updates since 20026, and Wyeth, the manufacturer of the PPI, pantoprazole (Protonix®; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Collegeville, PA), received the final updated request for pantoprazole pediatric studies from the FDA in 2007.

Pantoprazole delayed-release tablets are approved for marketing in the US for adults for the short-term treatment of erosive esophagitis associated with GERD, maintenance of healing of erosive esophagitis, and pathological hypersecretory conditions. The recommended adult dose is pantoprazole 40 mg daily.

Pantoprazole is primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 (CYP2C19)7, with minor metabolism involving CYP3A4. Individuals with at least one functional CYP2C19 allele, ie, *1, have normal CYP2C19 activity and are characterized phenotypically as extensive CYP2C19 metabolizers8. The most common nonfunctional CYP2C19 mutations are the *2 and *3 alleles9. Individuals who have these mutations on both alleles have nonfunctional CYP2C19, and are considered poor metabolizers, a phenotype that occurs in 2% of African Americans, 2.5–3.5% of Caucasians, and 12–20% of Asians8,9. In pediatric patients, development has the potential to influence the disposition of drugs that are extensively metabolized10, as reflected by a 21-fold variation in CYP2C19 activity in children between 5 months and 10 years of age11.

The primary purpose of the studies reported herein, which were conducted in response to a Pediatric Written Request from the US FDA, was to characterize the pharmacokinetics (PK) of pantoprazole following single and multiple oral doses of delayed-release tablets in children and adolescents with GERD. The secondary objective was to assess drug tolerability and short-term safety.

METHODS

Two multicenter, randomized, open-label, single- and multiple-dose studies were conducted in children with GERD. The studies were conducted in accordance with principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with Good Clinical Practice. An Institutional Review Board approved the protocol at each study site (a complete list of review boards is provided at the end). Written informed consent was obtained from parents and written assent was obtained for patients aged ≥7 years prior to patient enrollment. The clinical trial identifiers in the clinical studies registry, www.clinicaltrials.gov, are NCT00141817 for study 1 and NCT00367614 for study 2.

Study patients

Study 1 was conducted in children aged 1 year through 11 years; the patients aged ≥6 through 11 years (ie, aged ≥6 through aged <12 years) are described in this report, and the younger patients will be described in a separate report because they received a different formulation. Children had to have a clinical diagnosis of GERD that was confirmed by either endoscopic evidence of erosive esophagitis (Hetzel-Dent score ≥2 or Los Angeles classification grade A or above) or histologic evidence of reflux esophagitis without eosinophilic esophagitis. Females who had reached menstruation had to have a negative urine pregnancy test.

Study 2 was conducted in children aged 12 through 16 years who had a clinical diagnosis of suspected GERD, symptomatic GERD, or endoscopic evidence of GERD. A GERD diagnosis was defined as one or more of the following: clinical symptoms consistent with GERD, a diagnosis of erosive esophagitis by endoscopy, esophageal biopsy with histopathology consistent with reflux esophagitis, abnormal pH-metry consistent with reflux esophagitis, or other objective test result consistent with GERD. Sexually active patients had to agree to use an acceptable method of contraception. Females must have had negative pregnancy test results at screening (serum) and on days −1 and 1 (urine).

Exclusion criteria for both studies included the following: history of unrepaired tracheo-esophageal fistula or gastrointestinal (GI) malabsorption; clinically significant medical or surgical or laboratory abnormalities; presence of active childhood infectious diseases, coagulation disorders, immunodeficiency, hepatitis B or C or malignancy; hypersensitivity to any PPI; treatment with PPIs or other GI drugs (including prokinetic agents) for GERD or peptic ulcer within 24 hours before pantoprazole administration; use of antacids within 2 hours (study 1) or 4 hours (study 2) before or after pantoprazole administration; and disorders requiring chronic (daily) use of warfarin, carbamazepine, or phenytoin. Additionally, in study 1, patients with a history of an acute life-threatening event (near-sudden infant death syndrome) suspected to be related to GERD were excluded. In study 2, other exclusion criteria were current or past drug or alcohol abuse and a screening urine drug test result that was positive for a nonprescribed compound.

Study design

At the screening visit, patients in both studies were evaluated by medical history, physical examination, vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, temperature), 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs), laboratory tests (hematology, chemistry, coagulation, serum gastrin [fasting, if possible], and urinalysis) and pregnancy test. Patients in study 1 could have endoscopy and biopsy as part of screening if these procedures were not already done. Patients in study 2 had negative urine drug screen results at screening. On day 1, patients in both studies were randomly assigned in a 1:1 fashion to receive pantoprazole delayed-release 20-mg tablet (low dose) or 40-mg tablet (high dose).

On day 1, fasting patients received the first dose of pantoprazole in the clinic, followed by breakfast 30 minutes later. Three additional meals were provided over the 12-hour study period. Blood samples for analysis of pantoprazole concentrations were collected at ≤2 hours predose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 12 hours postdose for study 1, and at 2 hours predose and 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 6, 8, and 12 hours postdose for study 2. After day 1, pantoprazole was administered once daily at home, before breakfast with water. After at least 4 consecutive daily doses, patients returned to the clinic to receive the 5th dose. Pantoprazole was administered at approximately the same time as on day 1, with breakfast 30 minutes later, and blood samples were collected at 2 and 4 hours postdose to determine concentrations following multiple-dose administration.

In study 1, pantoprazole was dispensed at the clinic on days 1, 7, and 21, and the final day of pantoprazole treatment was day 28. In study 2, patients had their final visit on the day of their ≥5th consecutive dose in the clinic. Study 1 continued longer in order to provide additional treatment to the patients and a longer period for assessment of drug tolerability/safety.

Sample collection and analytical methods

Venous blood was obtained from an indwelling catheter or by direct venipuncture. Samples (5 mL each) were collected into tubes containing lithium heparin, gently mixed, placed on ice, and centrifuged within 15 minutes at 4°C at 1000g to ≤3000 g for 10 minutes. Plasma was separated into polypropylene tubes and stored at −70°C until they were shipped to the bioanalytical laboratory. At the time of shipment, plasma sample containers were placed onto dry ice to ensure their frozen stability.

Plasma samples were analyzed for pantoprazole concentrations using a validated LC/MS/MS method by AAI Kansas City, Shawnee, KS (now AAIPharma). Pantoprazole and the added internal standard, omeprazole, were extracted from sodium heparinized human plasma using liquid-liquid extraction. This extract was then subjected to reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography using an Aquasil C18, 5 μ (50 × 2.1 mm) analytical column. Pantoprazole and omeprazole in the effluent were detected using a PE/Sciex API 365 and API3000 LC/MS/MS systems in multiple reaction monitoring mode. The assay was linear to 5000 ng/mL, with a lower limit of quantitation of 10 ng/mL using 0.1 mL plasma. The accuracy and precision (% coefficient of variation), respectively, of the low, medium, and high quality control samples that were analyzed with the study samples were in the range of 92.00–98.06% and 2.68–4.93% for study 1, and 95.09–96.44% and 2.03–4.75% for study 2.

Buccal cells were obtained using a brush at any time from screening to the final visit, and the cellular DNA was isolated and purified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction-fragment analysis. Genotyping for common CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 allelic variants was performed using validated PCR and restriction-fragment analysis by Cogenics, Morrisville, NC.

Pharmacokinetics

Single-dose plasma pantoprazole concentration-vs-time data were analyzed using noncompartmental methods. WinNonlin Professional V 4.1 software (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA) was used to estimate peak pantoprazole concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (tmax), area under the concentration-vs-time curve from time zero to the time of the last measurable concentration (CT) (AUCT) and to infinity (AUC), terminal-phase disposition half-life (t1/2), apparent oral clearance (CL/F), and terminal-phase volume of distribution (Vz/F), where F is a bioavailability factor reflecting the fraction of the dose absorbed. The disposition rate constant (λz) was determined from the semilogarithmic fit of the terminal monoexponential portion of the concentration-vs-time values of 2 or more points (study 1) or 3 or more points (study 2) occurring after Cmax. The AUCT was calculated using the linear up/log down method. Half-life was calculated as t1/2 = ln2/λz. The AUC was estimated using AUC = AUCT + CT/λz. The CL/F and Vz/F were calculated as CL/F = dose/AUC and Vz/F = CL/λz. Values for CL/F and Vz/F were normalized by body weight. The lag time (tlag) was the time to the first observable plasma concentration.

In adults, pantoprazole has a half-life of approximately 1 hour, and repeated once-daily dosing does not result in accumulation12. Therefore, accumulation after repeated dosing was also not expected to occur in these 2 pediatric studies. After multiple-dose administration, samples were taken only at 2 and 4 hours during the disposition phase. This allowed avoidance of repeated blood draws while providing an estimation of concentration after multiple doses. Mean pantoprazole concentrations at 2 hours and 4 hours after ≥5 consecutive doses were summarized and compared with concentrations after the single dose.

Safety and tolerability

On day −1, patients underwent physical examination, including vital signs evaluation, and females had urine pregnancy testing. Patients and parents were given diaries for recording study drug intake, and they were given explanations about their use. On day 1, vital signs were monitored at 2 hours predose and 2, 8, and 12 hours postdose. On the day of the multiple-dose PK evaluation, daily diaries were collected, and patients underwent physical examination, including vital signs assessments, and laboratory tests in both studies; in addition, in study 2, patients had 12-lead ECG and females had a urine pregnancy test.

Patients in study 1 had a telephone follow-up on day 14; vital signs evaluation and physical examination on day 21; vital signs evaluation, physical examination, ECG, laboratory evaluations, and urine pregnancy testing on day 28 (final evaluation, final visit); and a final telephone follow-up 14 days (day 42) after study completion for monitoring of adverse events (AEs) and concomitant medications. Patients in study 2 had a final telephone follow-up on day 25. In both studies, on-treatment AEs were those that occurred during treatment with pantoprazole or within 48 hours of the last dose of pantoprazole.

Statistical analysis

The numbers of patients in each dose group for both studies were based on regulatory requirements outlined by the Pediatric Written Request, which required at least 12 patients. The sample size used in these studies had been sufficient to characterize single-dose PK in previous pantoprazole pediatric studies. Descriptive statistics for the single-dose PK parameters were determined for each dose group using WinNonlin Professional V 4.1. Comparison of PK parameters between the 20-mg and 40-mg dose groups within a given study was assessed using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test. Associations between subject age and pantoprazole PK parameters were explored using both linear and nonlinear regression analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted using the commercial software Microsoft Excel 2003 and assumed a significance level of α = 0.05.

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics, demographics, and treatment duration were similar between the dose groups for each study, and these data are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics of Children Aged 6 Through 11 Years (Study 1) and Adolescents Aged 12 Through 16 Years (Study 2) With GERD

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 20-mg Group (n = 11) | 40-mg Group (n = 13) | Total (n = 24) | 20-mg Group (n = 11) | 40-mg Group (n = 11) | Total (n = 22) |

| Age, mean ± SD (range), y | 8.6 ± 2.0 (6.0, 11.0) | 8.8 ± 1.1 (7.0, 11.0) | 8.7 ± 1.5 (6.0, 11.0) | 14.6 ± 1.6 (12.0, 16.0) | 14.2 ± 1.5 (12.0, 16.0) | 14.4 ± 1.6 (12.0, 16.0) |

| Males, n (%) | 7 (63.6) | 7 (53.9) | 14 (58.3) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (45.5) | 10 (45.5) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Black | 2 (18.2) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) | 6 (27.3) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (4.6) |

| White | 9 (81.8) | 11 (84.6) | 20 (83.3) | 8 (72.7) | 7 (63.6) | 15 (68.2) |

| Weight, mean ± SD, (range) kg | 33.6 ±10.8 (20.4, 57.1) | 37.2 ± 11.1 (24.4, 60.0) | 35.6 ± 10.9 (20.4, 60.0) | 70.5 ± 21.3 (46.4, 107.5) | 75.7 ± 29.1 (47.5, 126.6) | 73.1 ± 25.0 (46.4, 126.6) |

| Duration of therapy, mean ± SD (range), d | 27.0 ± 8.7 (1.0, 32.0) | 27.9 ± 1.9 (25.0, 31.0) | 27.5 ± 5.9 (1.0, 32.0) | 6.6 ± 2.3 (1.0, 9.0) | 7.8 ± 2.7 (5.0, 14.0) | 7.2 ± 2.5 (1.0, 14.0) |

d = day; SD = standard deviation; y = year.

Study 1

Study 1 was conducted from August 19, 2005 to November 20, 2007. Twenty-four patients aged 6 through 11 years were randomly assigned to treatment. One patient received pantoprazole granules instead of tablets and was discontinued. Twenty-three patients had a complete PK evaluation for the single-dose and multiple-dose PK analyses (low dose n=10; high dose, n=13).

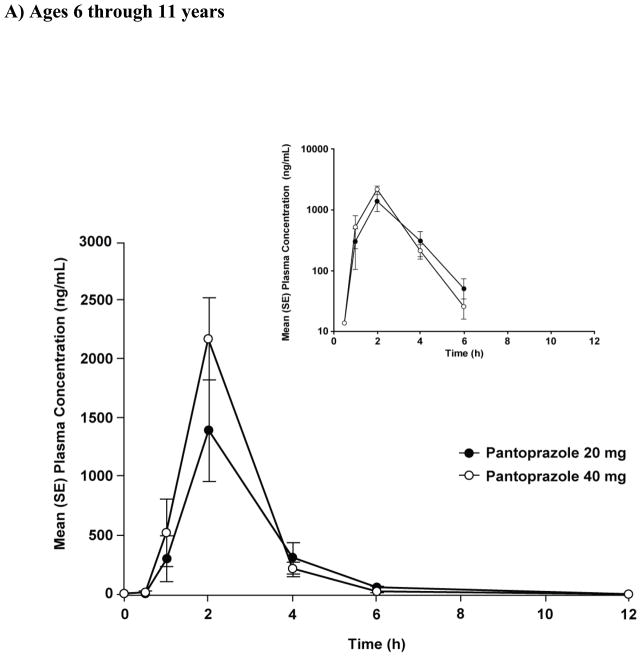

The mean concentration-vs-time profiles are shown in Figure 1A, and the PK parameters are shown in Table II. Individual and mean AUC values are plotted in Figure 2A. Both Cmax and AUC appeared to increase with dose. However, when these parameters were corrected for dose administered, eg, Cmax(corr) = mg/L per 1 mg/kg and AUCcorr = mg/L·h per 1 mg/kg, there was not a significant difference between the dose groups (20-mg vs. 40-mg, p>0.05) (Table II). The dose-independent parameters tlag, tmax, t1/2, CL/F, and Vz/F were similar between dose groups (Table II).

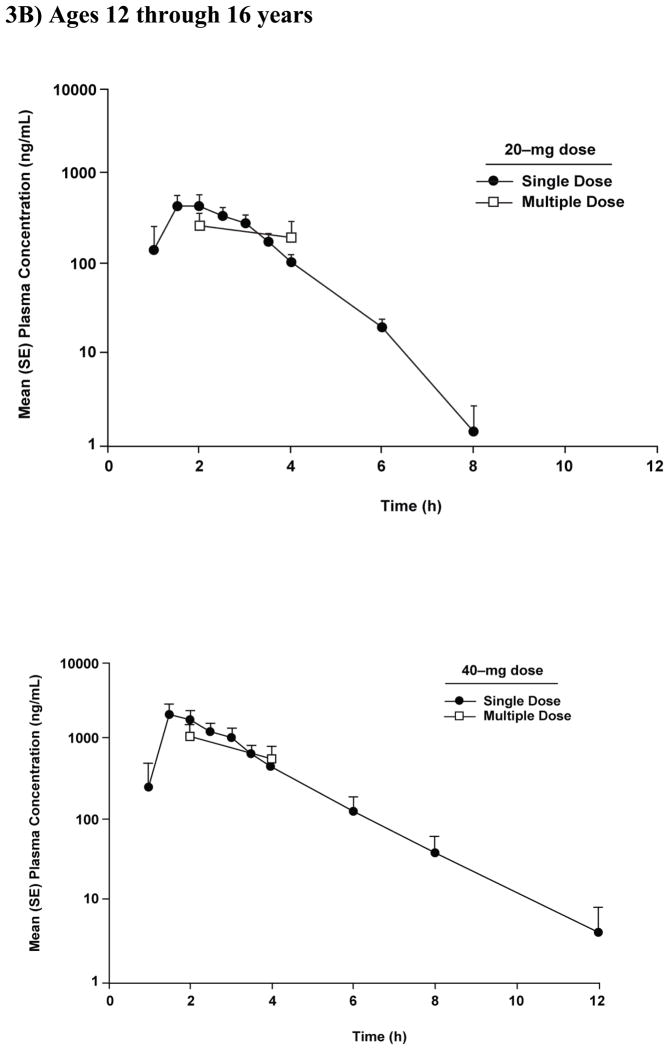

Figure 1.

Plasma concentration-time profiles after a single dose of pantoprazole tablet in (A) children aged 6 through 11 years (study 1) and (B) adolescents aged 12 through 16 years (study 2).

Table II.

Single-Dose Pharmacokinetics of Pantoprazole Delayed-Release Tablet in Children Aged 6 Through 11 Years (Study 1) and Adolescents Aged 12 Through 16 Years (Study 2)

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PK Parameter | 20 mg (n = 10) Mean ± SD | 40 mg (n = 13) Mean ± SD | 20 mg (n = 10) Mean ± SD | 40 mg (n = 11) Mean ± SD |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 1.4 |

| tmax (h)a | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0)b | 1.5 (1.0, 3.0)c | 2.0 (1.0, 12.0) |

| tlag (h)a | 1.0 (0.5, 2.0) | 0.8 (0, 1.0)b | 1.0 (0, 2.5)c | 1.0 (0, 8) |

| t1/2 (h) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2d | 0.8 ± 0.3c | 0.9 ± 0.3e |

| AUC (μg·h/mL) | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 3.8 ± 1.8d | 1.3 ± 0.6c | 4.3 ± 3.1e |

| AUCcorr (μg·h/L/1 mg/kg) | 3.9 ± 3.1 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | 4.8 ±2.7c | 6.9 ± 3.4e |

| Cmax(corr) (μg·h/L/1 mg/kg) | 2.6±1.8 | 2.1±1.1 | 3.2±1.9 | 3.7±1.8 |

| CL/F (L/h/kg) | 0.41 ± 0.30 | 0.40 ± 0.22d | 0.28 ± 0.17c | 0.18 ± 0.08e |

| Vz/F (L/kg) | 0.43 ± 0.30 | 0.40 ± 0.27d | 0.32 ± 0.22c | 0.21 ± 0.06e |

tmax and tlag are given as median (range).

n = 12,

n = 9,

n = 11,

n = 8

AUC = area under the concentration-time curve; AUCcorr = AUC normalized for a 1 mg/kg dose; CL/F = apparent oral clearance; Cmax = peak concentration; Cmax(corr) = Cmax normalized for a 1 mg/kg dose; SD = standard deviation; t1/2 = terminal-phase disposition half-life; tlag = lag time; tmax = time to peak concentration; Vz/F = apparent terminal-phase volume of distribution.

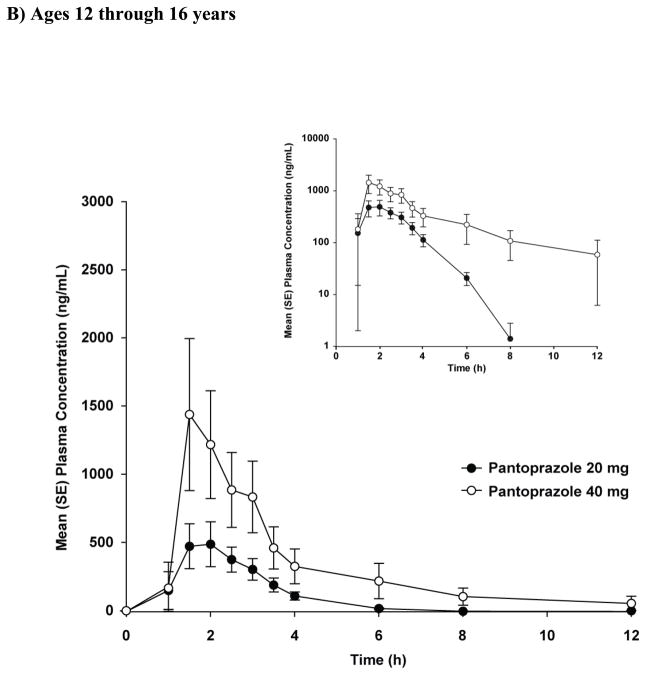

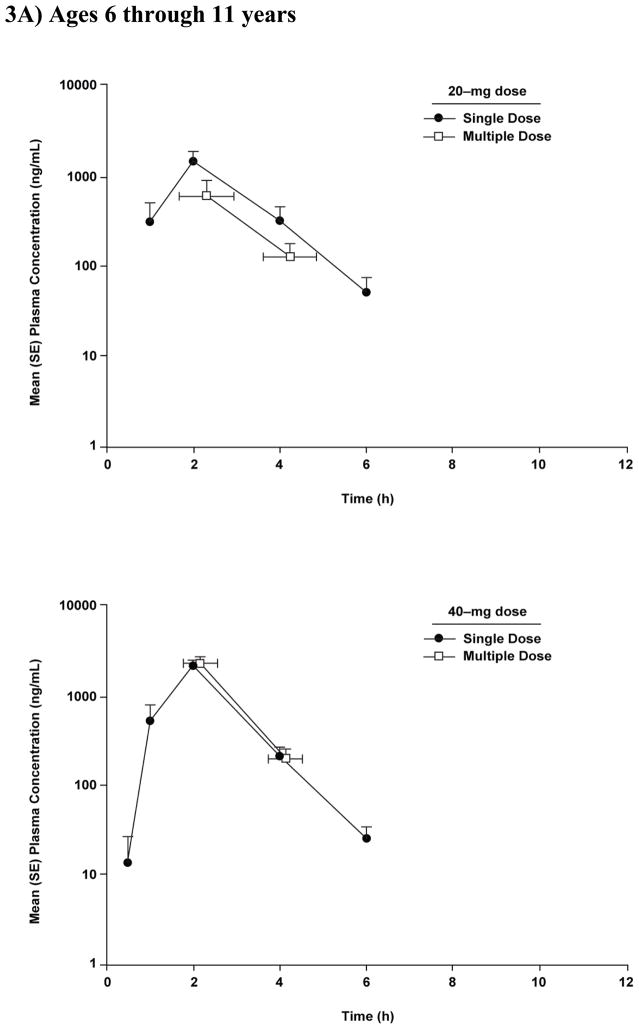

Figure 2.

Individual and mean AUC values after a single dose of pantoprazole tablet in (A) children aged 6 through 11 years (study 1) and (B) adolescents aged 12 through 16 years (study 2).

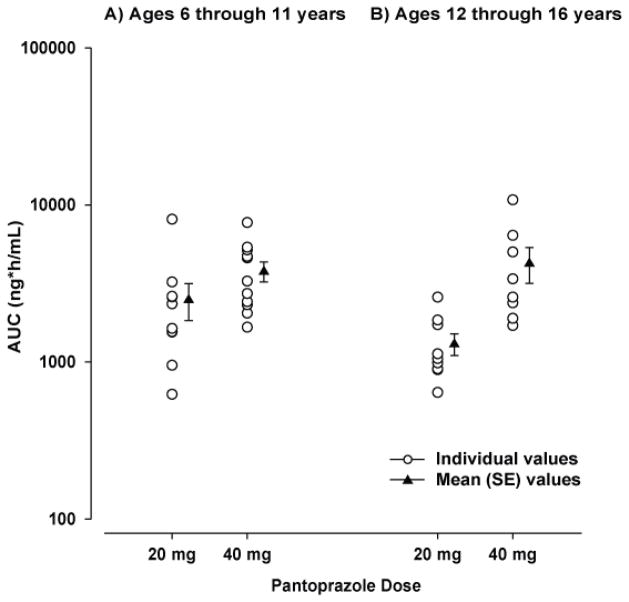

Graphical comparison of pantoprazole concentrations after single- and multiple-dose administration showed no evidence of accumulation after multiple-dose administration of either dose of pantoprazole in children aged ≥6 through 11 years (Figure 3A). In addition, for all patients, the concentration of pantoprazole at 12 hours after the first dose was below the lower limit of quantitation (Figure 1A).

Figure 3.

Mean (SE) plasma concentration-time profiles after single and multiple doses of pantoprazole tablet 20 mg and 40 mg in (A) children aged 6 through 11 years (study 1) and (B) adolescents aged 12 through 16 years (study 2).

Study 2

Study 2 was conducted from February 12, 2007 to August 13, 2007. Twenty-two patients aged 12 through 16 years were randomly assigned to treatment. One patient was discontinued because of loss of venous access. Twenty-one patients had a complete PK evaluation for the single- and multiple-dose PK analyses (low dose, n=10; high dose, n=11).

The mean concentration-vs-time profiles are presented in Figure 1B. Four patients had variable absorption that prevented single-dose PK calculations: 1 in the low-dose group had no measurable concentrations through 12 hours postdose and 3 in the high-dose group had a long apparent tlag in the range of 4 to 8 hours. The PK parameters are shown in Table II. Individual and mean AUCs are shown in Figure 2B. Cmax and AUC increased with dose and were not significantly different between dose groups (p>0.05) when corrected for dose (eg., Cmax = mg/L per 1 mg/kg and AUC = mg/L·h per 1 mg/kg) (Table II). The dose-independent parameters t1/2 and tlag were similar between dose groups. Three patients in the low-dose group had unusually high clearance resulting in higher mean clearance for that group.

Plasma pantoprazole concentrations at 2 and 4 hours after single- and multiple-dose administration in patients 12 through 16 years of age are shown in Figure 3B. There was no evidence of accumulation after multiple-dose administration of either the 20- or 40-mg dose (Figure 3B). In addition, for all patients, the concentration of pantoprazole at 12 hours after the first dose was below or close to the lower limit of quantitation (Figure 1B).

Clearance in study 1 and 2

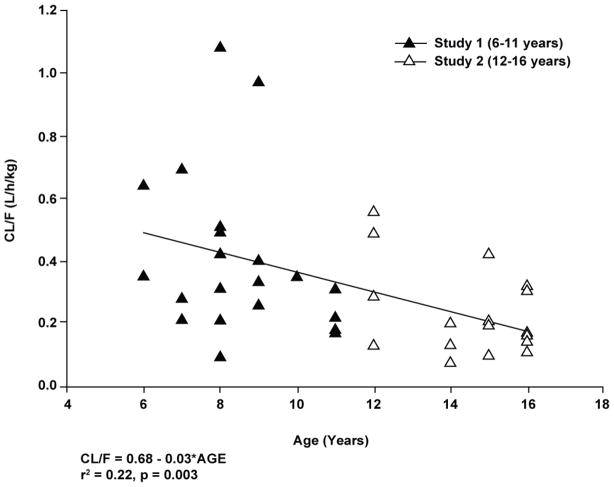

The plot of CL/F vs age for patients in both studies combined is shown in Figure 4. An apparent inverse linear association was observed between apparent pantoprazole total plasma clearance and age. While the association was statistically significant (p = 0.003 for linear regression), it was not considered to be predictive as age accounted for only 22% of the apparent clearance value with a coefficient of determination of 0.22.

Figure 4.

Individual values for clearance (CL/F) versus age after a single dose of pantoprazole tablet in patients aged 6 through 16 years (studies 1 and 2 combined).

Pharmacogenomics

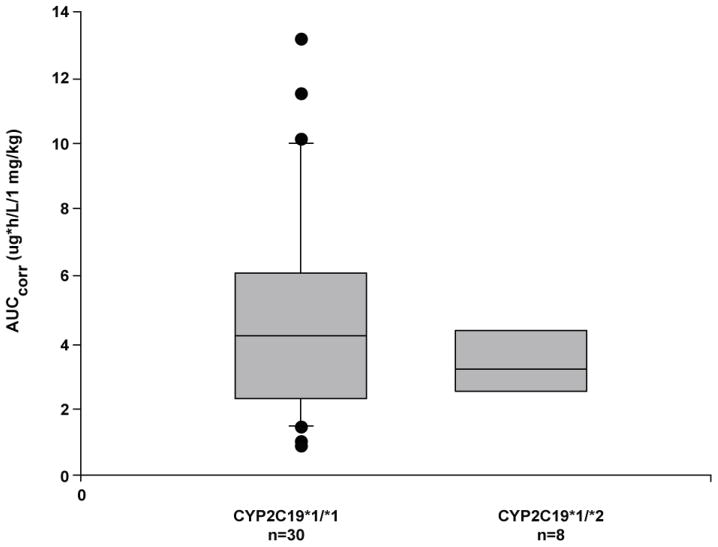

In both studies, all patients had a CYP2C19 genotype predictive of an extensive metabolizer phenotype. In study 1, 8 patients were heterozygous for CYP2C19*1/*2, 2 patients for CYP3A4*1/*1B, and 1 patient for CYP3A4*1/*3, and 1 patient was homozygous for CYP3A4*1B/*1B. In study 2, 3 patients were heterozygous for CYP2C19*1/*2 and 7 for CYP3A4*1/*1B, and 1 was homozygous for CYP3A4*1B/*1B. Patients who were heterozygous for CYP2C19 variants and patients homozygous or heterozygous for CYP3A4 all appeared to have extensive metabolizer phenotypes. Due to the high variability in absorption and the small number of patients in these subgroups, it was not possible to determine any potential subtle pharmacogenetic effects on clearance for these subgroups (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Box plot of pantoprazole area under the curve (AUC) normalized for dose versus CYP2C19 genotype in pediatric patients (studies 1 and 2 combined).

Safety and tolerability

In both studies, all randomized patients received ≥1 dose and, thus, were evaluable for safety. The duration of pantoprazole treatment is shown in Table I. All AEs were mild or moderate in severity. There were no discontinuations because of AEs, no serious AEs, and no statistically significant differences between the dose groups in the occurrence of any specific AEs in either study. AEs that occurred at an incidence ≥5% (ie, >1 patient) in either study are shown in Table III. In both studies, the most common AE was abdominal pain (Table III). One patient in study 1 accidentally took 2 doses of the 40-mg tablet with no associated AEs. None of the patients had clinically important abnormalities in laboratory test results, vital signs, or ECG (including no abnormal QTc changes).

Table III.

On-Treatment Adverse Events in Children Aged 6 Through 11 Years (Study 1) and Adolescents Aged 12 Through 16 Years (Study 2) With GERD During Administration of Pantoprazole Tablet (Total Incidence ≥5% in Either Study)

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | 20 mg (n = 11) | 40 mg (n = 13) | Total (n = 24) | 20 mg (n = 11) | 40 mg (n = 11) | Total (n = 22) |

| Any AE | 9 (81.8) | 7 (53.8) | 16 (66.7) | 2 (18.2) | 4 (36.4) | 6 (27.3) |

|

| ||||||

| Specific AEs | ||||||

| Abdominal pain | 3 (27.3) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 2 (9.1) |

| Accidental injury | 1 (9.1) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 1 (9.1) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (4.5) |

| Headache | 1 (9.1) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (12.5) | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (4.5) |

| Otitis media | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 2 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Upper respiratory infection | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 2 (8.3) | |||

AE = adverse event.

DISCUSSION

In adults, pantoprazole has predictable, dose-linear PK, no accumulation after multiple dosing, and a low potential for drug-drug interactions13. A recent study demonstrated that the PK of intravenous (IV) pantoprazole does not vary as a consequence of development across the ages of 2 to 16 years, and that the PK profile of a single dose of IV pantoprazole in this age group was similar to that in healthy adults14.

We characterized the PK profile of pantoprazole delayed-release tablet 20 mg and 40 mg in children aged 6 through 11 years with endoscopically proven GERD (study 1) and in adolescents aged 12 through 16 years with a clinical diagnosis of suspected GERD (study 2).

The mean AUC for the 20- and 40-mg doses, respectively, was 2.5 and 3.8 μg·h/mL in study 1, and 1.3 and 4.3 μg·h/mL in study 2. These values were comparable to those in the previously published pediatric PK study14, as well as those in adults15. The AUCcorr was slightly lower in the 6- to 11-year-old age group compared with that in the adolescents and can probably be attributed to the slightly higher clearance in this age group.

In the current studies, Cmax and AUC increased with increasing doses of pantoprazole. The increases were not exactly dose proportional, perhaps because of the small sample sizes and high degree of inter-subject variability in PK. Similar variability has been observed in the PK of other PPIs in children16. Dose linearity for pantoprazole is observed in adults13 and has been reported in children aged 2 to 16 years14. For all PPIs, the extent of acid suppression is well correlated with systemic drug exposure reflected by AUC17. AUC and Cmax have been used successfully to establish the most beneficial PPI exposure in adults. However, this exposure-to-benefit relationship is less clear in pediatric patients, despite the fact that PK profiles appear similar between adults and children and adolescents12,13.

As illustrated in Figure 4, a weak inverse association was observed between pantoprazole apparent oral clearance (CL/F) and age, a finding suggestive of some degree of developmental dependence in pantoprazole clearance for patients between 6 and 16 years of age. Similar relationships have been reported with other proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, esomeprazole and lansoprazole),16,18,19 and recently, with pantoprazole administered by the intravenous route20. As denoted in a recent commentary by Holford21, the allometric relationship between age and body size (ie, age and body weight) produces the apparent inverse relationship between weight-normalized drug clearance and age. To validate this assertion, the data contained in Figure 4 were re-analyzed using an allometric ¾ power model22, which failed to demonstrate a statistically significant association with age (data not shown). In contrast, as also denoted by Holford21, the maturation of pathways responsible for drug elimination (eg, drug metabolizing enzymes, renal maturation) are more important determinants of drug clearance than body size. This principle is also evident in the fact that the mean CL/F of pantoprazole in neonates was 2-fold lower (mean = 0.22 L/h/kg) than that observed in children ages 6–11 years23 and clearance of pantoprazole in adolescents was similar to that observed in adults12. These data corroborate the simulations described by Pettersen et al.20 and, given the predominance of CYP2C19 in the biotransformation of pantoprazole, are supported by the known developmental expression profile for this drug metabolizing enzyme in humans24.

Within each of the current studies, mean values for the dose-independent parameters half-life, tmax, and tlag were similar between the 2 doses and were also similar across the 2 studies. Accumulation of pantoprazole is not observed in adults13, which is consistent with the short half-life of the drug. In the current studies, comparisons of mean concentration-vs-time profiles after single and multiple doses in 44 patients do not demonstrate drug accumulation after multiple doses.

In contrast to the elimination half-life data from the current study, the apparent plasma clearance and volume of distribution were, in general, highly variable, presumably due to the uncertainty of the bioavailability factor. This assertion is reflected by the data in four of the adolescent patients that were “non-pharmacokinetic” in that these patients had an unexpectedly long apparent lag time (4–8 hours) or no observable pantoprazole concentrations through 12 hours postdose. It is possible that these incidents could be attributed to either delayed gastric emptying of the tablet, variable absorption from the small intestine, or failure of dissolution of the enteric coating of the tablet during the PK sampling period25. Dosage records showed that pantoprazole was taken at the specified time.

An additional source of variability in the observed pharmacokinetic parameters resides with the impact of pharmacogenetics on pantoprazole disposition. Genotypic variants of CYP enzymes can contribute to variability in PK profiles and absorption of PPIs. In both adults and children, CYP2C19 poor metabolizers treated with therapeutic doses of pantoprazole have significantly increased plasma concentrations and AUC with longer t1/2, and lower apparent oral clearance7,14,26. There were no poor metabolizers of CYP2C19 in the 2 current studies. As well, there were too few patients who were heterozygous for CYP2C19 (Figure 5) to draw any definitive conclusions regarding the effect of genotype on the biotransformation of pantoprazole in the study cohorts. As the CYP2C19*17 allele was not evaluated as part of the study protocols consequent to its test not being available from the reference laboratory conducting the genotyping, its potential impact on the pharmacokinetic parameters could not be assessed in the current investigation27.

Finally, pantoprazole was generally safe and well tolerated in these studies. There were no serious AEs and no discontinuations due to AEs. Abdominal pain was the most commonly reported AE, and it is also a less recognized but relatively common mode of presentation of GERD28. No dose-relationship was observed in the incidence of any AEs.

CONCLUSIONS

Pantoprazole was generally safe and well tolerated in children aged 6 through 11 years who were treated with 20 or 40 mg daily for approximately 1 month as well as in adolescents aged 12 through 16 years who were treated with 20 or 40 mg daily for at least 5 consecutive doses. Systemic exposure with the 40-mg dose in children 6 through 11 years and 40-mg dose in adolescents 12 through 16 years appeared similar to that in adults after administration of pantoprazole 40 mg daily. The results support the use of the 40-mg dose in children and adolescents aged 6 through 16 years with GERD. However, doses of 20 mg may be sufficient in smaller children (<40 kg) for the treatment of GERD symtpoms29,30 as reflected in current US Protonix® labeling12.

IRB LIST FOR INVESTIGATIVE SITES

IRB LIST FOR STUDY 1

The IRB for Phyllis Bishop, University of Mississippi Medical Center, was University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216-4505

The IRB for Victor Nizet, University of California at San Diego/San Diego Children’s Hospital and Health Center, was University of California, San Diego, Human Research Protections Program, La Jolla Village Professional Center, 8958 Villa La Jolla, Suite A208, La Jolla, CA 92037

The IRB for Gregory L. Kearns, The Children’s Mercy Hospital, was Children’s Mercy Hospitals & Clinics, 2401 Gillham Road, Suite HHC600, Kansas City, MO 64108

The IRB for Regino Gonzalez-Peralta, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL 32601, was Western Institutional Review Board, 3535 Seventh Avenue, SW, Olympia, WA 98502

The IRB for Thirumazhisai Gunasekaran, Advocate Lutheran General Children’s Hospital, was Advocate Health Care IRB, 205 W. Touhy, Suite 203, Park Ridge, IL 60068-4202

The IRB for Sandeep Gupta, Indiana University Medical Center, James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children, was IUPUI and Clarian Institutional Review Boards & Subcommittee Reviews, 620 Union Drive, Union Bldg., Room 618, Indianapolis, IN 46202

The IRB for John Pohl, Scott & White Memorial Hospital and Clinic, was Scott & White Institutional Review Board, 2401 S. 31st Street, Alexander Bldg., Temple, TX 76508

The IRB for Alan Sacks, Nemours Children’s Clinic, Pensacola of the Nemours Foundation, was Nemours Florida IRB, 807 Children’s Way, Jacksonville, FL 32207

The IRB for Ali Bader and John van den Anker, Children’s National Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, was Children’s National Medical Center, 111 Michigan Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20010-2970

The IRB for Robert Ward, University of Utah, was University of Utah Institutional Review Board, RAB 512, 75 South 2000 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-8930

IRB LIST FOR STUDY 2

The IRB for Phyllis Bishop, University of Mississippi Medical Center, was University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216-4505

The IRB for Janice E. Sullivan, Kosair Charities Pediatric Clinical Research Unit/Pediatric Pharmacology Research Unit was Human Subjects Protection Program University of Louisville, MedCenter One, Suite 200, 501 East Broadway, Louisville, KY 40202

The IRB for Mitchell H. Katz, Children’s Hospital of Orange County, was Children’s Hospital of Orange County IRB, 455 South Main Street, Orange, CA 92868

The IRB for Gregory L. Kearns, The Children’s Mercy Hospital, was Children’s Mercy Hospital Pediatric IRB, 2401 Gillham Road, Suite HHC600, Kansas City, MO 64108

The IRB for Laura P. James, Arkansas Children’s Hospital, was Human Research Advisory Committee, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham, Mail Slot 636, Little Rock, AR 72205

The IRB for V. Marc Tsou, Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters, was Eastern Virginia Medical School IRB, 721 Fairfax Ave., Suite 512, Norfolk, VA 23507

The IRB for Molly A. O’Gorman, University of Utah, was University of Utah Institutional Review Board, RAB 512, 75 South 2000 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-8930

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the parents and children for their involvement in these studies. The studies were conducted by Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfizer Inc. in Oct. 2009. Medical writing support was provided by Tuli Ahmed, medical writer, of On Assignment, and funded by Wyeth.

The following were investigators in study 1:

Ali Bader and John van den Anker, Children’s National Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC; Phyllis Bishop, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS; Regino Gonzalez-Peralta, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL; Thirumazhisai Gunasekaran, Advocate Lutheran General Children’s Hospital, Park Ridge, IL; Sandeep Gupta, Indiana University Medical Center, James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, IN; Gregory L. Kearns, The Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO; Victor Nizet, University of California at San Diego/San Diego Children’s Hospital and Health Center, San Diego, CA; John Pohl, Scott & White Memorial Hospital and Clinic, Temple, TX; Alan Sacks, Nemours Children’s Clinic, Pensacola of the Nemours Foundation, Pensacola, FL; and Robert Ward, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT.

The following were investigators in study 2:

Phyllis Bishop, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS; Laura P. James, Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, AR; Mitchell H. Katz, Children’s Hospital of Orange County, Orange, CA; Gregory L. Kearns, The Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO; Molly A. O’Gorman, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT; Janice E. Sullivan, Kosair Charities Pediatric Clinical Research Unit/Pediatric Pharmacology Research Unit (NICHD funded through grant U10 HD045934-04), University of Louisville, Louisville, KY; and V. Marc Tsou, Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters, Norfolk, VA.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

This study was funded in full by Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfizer Inc. in October 2009. R.M. Ward has been a paid consultant to Wyeth in the design of pediatric studies of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and has supervised the pediatric studies of PPIs by the University of Utah Pediatric Pharmacology Program for Wyeth, TAP, Eisai, and AstraZeneca. G.L. Kearns has served as a paid consultant to Wyeth with regard to the design of pediatric pharmacokinetic studies of PPIs and has supervised the study of drugs in this class conducted by Wyeth, TAP, and AstraZeneca at the Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics. M. O’Gorman has received funding for serving as an investigator for Wyeth. L.P. James has served as a local investigator for studies examining PPIs performed by the Arkansas Children’s Hospital Pediatric Pharmacology Research Unit for Wyeth, Eisai, TAP, and AstraZeneca. M.H. Katz was an investigator in study 2 and his institution received funding from Wyeth for his participation. B. Tammara, M.K. Maguire, N. Rath, X. Meng, and G.M. Comer were employees of Wyeth at the time of the study and manuscript preparation. Medical writing support was provided by Tuli Ahmed, of On Assignment, and was funded by Wyeth.

References

- 1.Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498–547. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181b7f563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, et al. A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278–1295. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz DM, Winter HS, Colletti RB, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practice styles of North American pediatricians regarding gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:56–64. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318054b0dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter JE, Fraga P, Mack M, Sabesin SM, Bochenek W Pantoprazole US GERD Study Group. Prevention of erosive oesophagitis relapse with pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:567–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassall E, Kerr W, El-Serag HB. Characteristics of children receiving proton pump inhibitors continuously for up to 11 years duration. J Pediatr. 2007;150:262–267.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo-Torres H. Briefing document for June 11, 2002 Advisory Committee meeting on the proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) template. [Accessed January 25, 2010];Justification for studies in pediatric patients. 2002 http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/02/briefing/3870B1_02_Briefing%20document.pdf.

- 7.Tanaka M, Ohkubo T, Otani K, et al. Metabolic disposition of pantoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, in relation to S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation phenotype and genotype. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;62:619–628. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furuta T, Shirai N, Sugimoto M, Ohashi K, Ishizaki T. Pharmacogenomics of proton pump inhibitors. Pharmacogenomics. 2004;5:181–202. doi: 10.1517/phgs.5.2.181.27483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leeder J. Pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:765–781. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental pharmacology -- drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1157–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benedetti MS, Whomsley R, Canning M. Drug metabolism in the paediatric population and in the elderly. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PROTONIX® (pantoprazole sodium) delayed-release tablets and PROTONIX® (pantoprazole sodium) for delayed-release oral suspension (U.S. package insert) Collegeville, PA: Wyeth; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huber R, Hartmann M, Bliesath H, Luhmann R, Steinijans VW, Zech K. Pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole in man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;34:185–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kearns GL, Blumer J, Schexnayder S, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous pantoprazole in children and adolescents. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48:1356–65. doi: 10.1177/0091270008321811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon B, Muller P, Marinis E, et al. Effect of repeated oral administration of BY 1023/SK&F 96022 - a new substituted benzimidazole derivative - on pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion and pharmacokinetics in man. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:373–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Litalien C, Theoret Y, Faure C. Pharmacokinetics of proton pump inhibitors in children. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:441–466. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearns G, Winter H. Proton pump inhibitors in pediatrics: relevant pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37(suppl 1):S52–S59. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200311001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson T, Hassall E, Lundborg P, et al. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered omeprazole in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3101–3106. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao J, Li J, Hamer-Maansson JE, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties of esomeprazole in children aged 1 to 11 years with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized, open-label study. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1868–1876. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pettersen G, Moukassi M-S, Theoret Y, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous pantoprazole in paediatric intensive care patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:216–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holford N. Dosing in children. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:367–370. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson B, Holford NHG. Mechanism-based concepts of size and maturity in pharmacokinetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:303–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward RM, Tammara B, Sullivan SE, et al. Single-dose, multiple-dose, and population pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole in neonates and preterm infants with a clinical diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010 March 20; doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0811-8. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koukouritaki SV, Manro JR, Marsh SA, et al. Developmental expression of human hepatic CYP2C9 and CYP2C19. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:965–974. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horn J, Howden C. Review article: similarities and differences among delayed-release proton-pump inhibitor formulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(suppl 3):20–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka M, Yamazaki H, Hakusui H, Nakamichi N, Sekino H. Differential stereoselective pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor in extensive and poor metabolizers of pantoprazole—a preliminary study. Chirality. 1997;9:17–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1997)9:1<17::AID-CHIR4>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunfeld NG, Mathot RA, Touw DJ, et al. Effect of CYP2C19*2 and *17 mutations on pharmacodynamics and kinetics of proton pump inhibitors in Caucasians. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:752–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassall E. Decisions in diagnosing and managing chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. J Pediatr. 2005;146(suppl 3):S3–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolia V, Bishop P, Tsou V, et al. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind study comparing 10, 20 and 40 mg pantoprazole in children (5–11 years) with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:384–391. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000214160.37574.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsou VM, Baker R, Book L, et al. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind study comparing 20 and 40 mg of pantoprazole for symptom relief in adolescents (12 to 16 years of age) with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2006;45:741–749. doi: 10.1177/0009922806292792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]