Abstract

This study was designed to develop a framework for understanding parents’ perspectives about the psychosocial consequences of false-positive newborn screening (NBS) results for cystic fibrosis (CF). Through content analysis of interviews with 87 parents of 44 infants, we found that receipt of genetic information through NBS affected parents on intrapersonal and interpersonal levels within a relational family system. Repercussions included wondering about test accuracy, the child’s health, and the future; gaining new perspectives and strengthening relationships; questioning paternity; wondering if other relatives had CF/were carriers; searching for the genetic source; sharing genetic information; supporting NBS; and feeling empathy for parents of affected children. We concluded that abnormal NBS results that involve genetic testing can have psychosocial consequences that affect entire families. These findings merit additional investigation of long-term psychosocial sequelae for false-positive results, interventions to reduce adverse iatrogenic outcomes, and the relevance of the relational family system framework to other genetic testing.

Keywords: content analysis; cystic fibrosis; infants; psychosocial issues; research, qualitative; screening

Presymptomatic infants with genetic and/or metabolic conditions have been identified through newborn screening (NBS) for nearly 50 years. Detecting these disorders as early as the first few days of life facilitates rapid initiation of treatment to prevent morbidity and optimize health outcomes for innumerable infants. Since the inception of NBS in the 1960s, the number of conditions screened through statewide programs has increased rapidly because of technological advances, e.g., tandem mass spectrometry. More recently, genetic testing has made it possible to detect heritable disorders from a few drops of blood (Newborn Screening Task Force, 2000).

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common life-threatening, autosomal recessive genetic disease in the United States. CF is most common in the White population, with a frequency of 1 per 3,500 births; however, it has been seen in most racial/ethnic groups. The presence of two abnormal CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) genes causes a defect in electrolyte transfer at the cellular level, resulting in abnormally thick secretions in the respiratory, digestive, and reproductive systems. Complications include chronic lung infection, nutritional malabsorption, and male infertility. Although advances in treatment have improved the length and quality of life for people with CF, the diagnosis still carries a shortened life expectancy, with an approximate median survival of 37 years (Farrell et al., 2008).

In 1991, CF became the model for incorporating DNA analysis into NBS programs in the United States (Sharp & Rock, 2008). Genetic testing via NBS can detect presymptomatic infants with the condition; however, it also identifies heterozygote CF carriers and infants with nondisease causing mutations who are otherwise healthy. Using the two-step immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) and DNA analysis procedure, infants with an elevated IRT level plus one or two CF mutations undergo an additional diagnostic sweat test to rule out or confirm the diagnosis. An abnormal NBS result that identifies one CFTR mutation followed by a normal sweat test is referred to as a false-positive NBS result, and indicates the infant is a CF carrier who does not have the disease. Therefore, at least one parent is also a CF carrier and the couple could be at risk for conceiving a child with CF. Additional genetic testing is advised for these couples if they plan to have more children. The rate of false-positive CF NBS results varies based on screening methods and the infant’s racial/ethnic background (Giusti & New York State Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Consortium, 2008). About 97% of infants with one CFTR mutation identified through NBS have false-positive results (Rock et al., 2005). Given the complexity of DNA-based NBS, genetic counseling is offered to families at the time of the follow-up diagnostic sweat test.

Psychosocial Sequelae of False-Positive NBS

The health benefits of early CF detection through NBS have been well documented (Farrell et al., 1997; Farrell et al., 2001). Therefore, concerns are focused primarily on potential psychosocial risk, particularly for the false-positive population for whom NBS offers no health benefits (Duff & Brownlee, 2008). These concerns include parental misunderstanding of test results (Ciske, Haavisto, Laxova, Rock, & Farrell, 2001), undue worry about infants (Lewis, Curnow, Ross, & Massie, 2006), frustration with the process (Moran, Quirk, Duff, & Brownlee, 2007), and the influence on reproductive decisions (Mischler et al., 1998). Other research has focused on the effects of false-positive results on parents’ relationships with their children. Baroni, Anderson, and Mischler (1997) found that parents of infants with false-positive NBS results for CF had significantly lower total stress scores but significantly higher defensiveness scores on the Parenting Stress Index than a comparison of parents whose infants had normal NBS results. The authors interpreted high defensiveness scores as evidence of “hypervigilance and repressed emotion.” Parsons, Clarke, and Bradley (2003) found no significant differences on measures of infant rejection, overprotection, anxiety, or perceptions of well-being reported by parents of infants diagnosed with CF, those with false-positive NBS results, or those with normal results. However, these studies had methodological limitations such as small samples and the use of force-choice responses that did not capture the more nuanced ways in which parents assimilate their interpretations of test results into their lives.

This project was one in a series of reports from a larger study that examined parents’ reported experiences at various junctures in the NBS process. The authors focused the content analysis in this study on concepts emerging from the results of the grounded theory methods used in earlier studies. Parents of infants with abnormal NBS results for CF reported significant emotional distress during the days or weeks they waited for their infants’ diagnostic testing (Tluczek, Koscik, Farrell, & Rock, 2005). In another study, parents identified aspects of the counseling they received during their infants’ diagnostic sweat test appointments that contributed to ameliorating or exacerbating their distress (Tluczek et al., 2006). When genetic counseling matched parents’ needs for information and emotional support, parents reported feeling reassured, whereas mismatched counseling was associated with parental confusion and worry. Parents of infants with equivocal diagnostic results reportedly passed through a series of stages of uncertainty that led them to develop strategies to decrease or manage the uncertainty of their infants’ prognosis (Tluczek, McKechnie, & Lynam, in press). The purpose of this study was to develop a more comprehensive picture of parents’ perspectives of NBS by examining parents’ understanding of their infants’ false-positive NBS results and how their knowledge of an infant’s carrier status affected them and their interactions with other family members during the infant’s first year of life.

Method

Design and Procedures

This article contains the results of primary directed and summative analyses (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) of a subset of qualitative data obtained from extensive interviews that were part of a larger, longitudinal mixed-method project examining the psychosocial consequences of genetic testing applied to NBS (Tluczek, Clark, Koscik, & Farrell, 2005). The analyses of other subsets of the interview data have been published elsewhere. Procedures included data sampling, recording, utilizing, reducing, inferring, and narrating the results described by Krippendorff (2004). The institutional review boards of all four participating medical centers approved this study. Participants provided written consent after the study had been described and their questions answered. The consent procedure included a discussion about the use of nonidentifying quotes in publications and whether parents would like to receive a summary of findings at the end of the study. The principal investigator maintained a list of participants who requested study results and a summary will be mailed to those parents when all data have been analyzed and articles generated from this project have been published.

Sampling

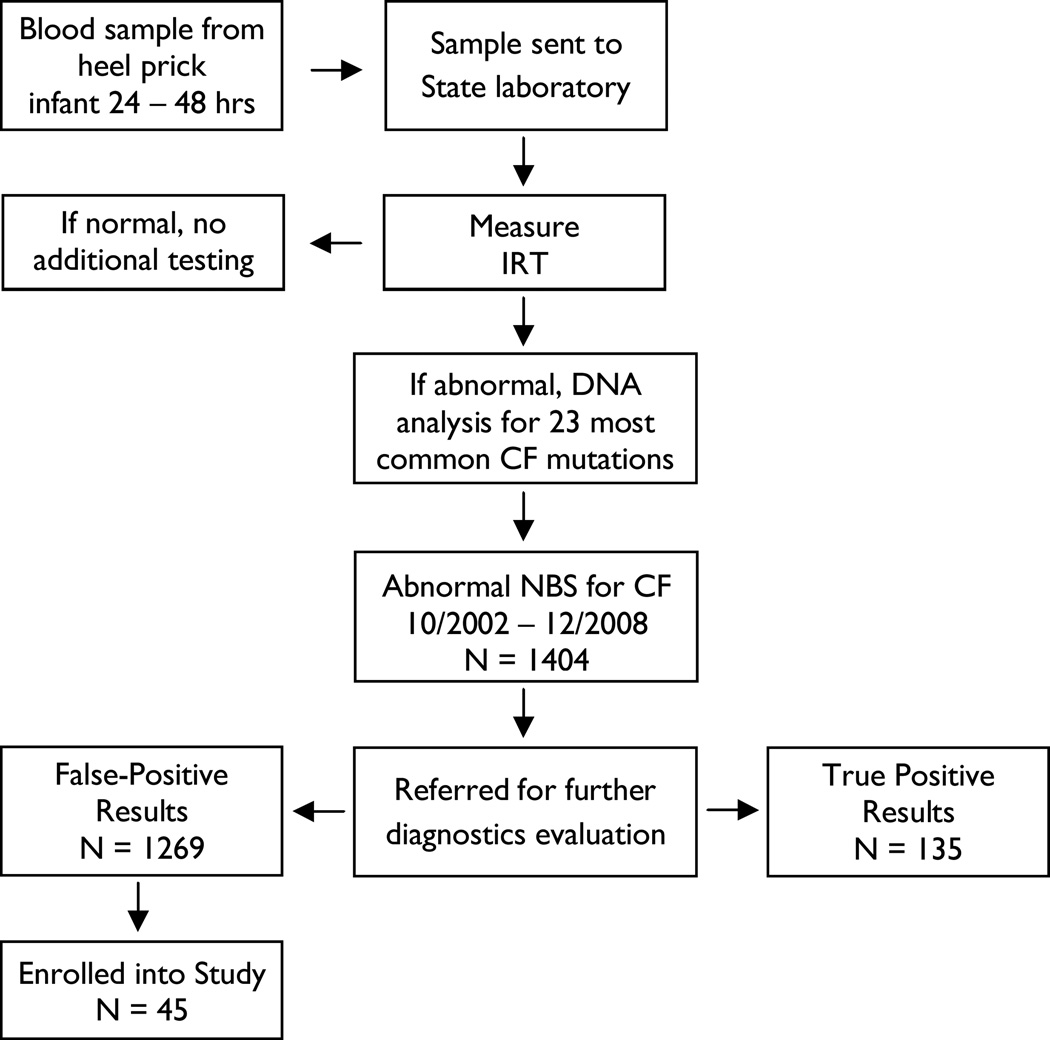

Convenience sampling techniques were used to recruit families who met inclusion criteria. Although the larger research project included families with a range of NBS results, this analysis was limited to a sample with false-positive CF NBS results that identified CF carriers. As illustrated in Figure 1, about 4% of infants with false-positive NBS results for CF between October 1, 2002, and June 30, 2008, participated in this study. Parents of infants who were born at less than 32 weeks gestation, were diagnosed with serious health problems, or had low APGAR scores (≤ 3) were excluded. Genetic counselors mailed study invitations with the genetic counseling summary letters routinely sent to parents following the diagnostic sweat test appointment. Parents who were interested in the study contacted the principal investigator (PI) by telephone or mail. During initial telephone conversations with parents, the PI explained the study, answered parents’ questions, and scheduled data collection. The extensive statewide recruitment effort precluded documenting response rates.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for CF NBS and study enrollment

The sample for this analysis included 87 parents of 44 infants who were identified as CF carriers through NBS between 2002 and 2008. All participants were the biological parents of screened infants and were White European Americans with mean ages of 29 years for mothers and 30 years for fathers. Most were married (75% mothers, 77% fathers), had some postsecondary education (82% mothers, 64% fathers), and reported a family income of $41,000 or more (57% mothers, 62% fathers). The average number of children in the family was two. Infant genders showed a slight female majority (55%).

Data collection

A semistructured interview was developed based on the results of an earlier grounded theory study (Tluzcek, Koscik, et al., 2005). Interview data for this article were part of extensive interviews that addressed a wide range of topics and from parents of infants with a variety of NBS test results. The data analyzed for this article narrowly focused on parents’ understanding of false-positive NBS test results, the meaning of being a CF carrier, parents’ memories of the NBS experience, the impact of genetic findings on family relationships, and whether parents supported NBS for CF. Follow-up questions elicited additional details and examples. Questions posed at the first data point included (a) What is your understanding of the results of the sweat test? and (b) How has the presence of the CF gene affected other family members? The 12-month follow-up interview questions included (a) What do the results of the sweat test (child had first few weeks of life) mean to you? (b) How often in the last 6 months have you thought about newborn screening? (c) How has the presence of the CF gene in your family tree affected other family members? (d) Some other families have described finger-pointing between families to locate the gene. I’m wondering if you have experienced this. (e) Based on your experience, do you think we should be doing newborn screening for CF? Why/why not?

If both parents participated, they were interviewed together. The PI or specially trained data collectors conducted the 20- to 30-minute tape-recorded interviews in families’ homes when infants were about 6 to 12 weeks old and again at about 12 months of age. The PI used an apprentice model to train data collectors through selected readings in qualitative methods, review of transcribed interviews conducted by the PI, direct observation of interviews, and personal supervision of trainee interviews. A member of the research team transcribed the audio tapes verbatim, editing out identifiers. Another researcher cross checked the final transcriptions for accuracy. The PI randomly examined audiotaped and transcribed data for consistency and provided remedial training for data collectors as needed. The final data set for this study consisted of 44 interviews at 6 to 12 weeks and 39 interviews at 12 months.

Coding, reducing, and inferring data

The PI trained and supervised a multidisciplinary research team to conduct line-by-line analysis of transcripts. The team abstracted textual units to reduce data to core categories. We developed a system for defining, coding, and categorizing data based on thematic similarities and differences within each category. Data with similar themes were clustered together, labeled with descriptive codes, and stored in separate electronic databases. We also compared thematic codes and categories across the two data points. When consensus about codes and definitions was reached, coder reliability was established by having all coders, including the PI, analyze the same data sets until at least 90% interrater reliability had been attained. Thereafter, when questions arose about how to code a particular unit of data, the PI was consulted. Throughout the analytic process, codes and categories were reappraised and refined to assure descriptive, interpretive, theoretical, and evaluative validity (Maxwell, 1992). The analysis resulted in the seven major themes and 13 categories listed in Table 1, for which frequencies were also tabulated. The categories were clustered into similar domains. We reexamined the literature for evidence of similar findings. Finally, we conceptualized the findings within a relational family systems perspective.

Table 1.

Psychosocial Consequences of False-Positive Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening

| Major Themes and Related Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Intrapersonal Level | |

| Understanding | |

| Accurately understood sweat test results | 87 (100) |

| Accurately understood cystic fibrosis genetics | 63 (72.4) |

| Personal Meaning | |

| Remembering the newborn screening experience | 15 (17.2) |

| Feeling guilt for passing defective gene to child | 9 (10.3) |

| Interpersonal Level | |

| Parent-child Relationship | |

| Wondering about the accuracy of sweat test | 11 (12.6) |

| Wondering about the future | 9 (10.3) |

| Other Children or Parent Siblings | |

| Wondering if other family members have cystic fibrosis or are carriers | 8 (9.2) |

| Spousal Relationship | |

| Gaining new perspective s and strengthening relationships | 13 (14.9) |

| Questioning paternity | 1 (1.1) |

| Extended Family Relationships | |

| Finger pointing in searching for the genetic source | 11 (12.6) |

| Sharing genetic information with family | |

| Opportunity | 7 (8.0) |

| Burden | 5 (5.7) |

| Relationships With Community | |

| Feeling empathy for parents of children with cystic fibrosis | 4 (4.6) |

| Supporting NBS | |

| Fully support | 62 (71.3) |

| Conditional or ambivalent support | 11 (12.6) |

| No response | 18 (20.7) |

Statistical analysis

After completing the qualitative analysis, we used an exact logits modeling procedure to examine the relationship between parent age, education, and infant birth order as possible predictors of the various dichotomous (present/absent) outcome measures for the 13 categories. Because the numbers in each category were small, we combined mothers and fathers and used parent as a variable in the model.

Results

Findings from this study suggested that abnormal genetic test results affected parents on intrapersonal and interpersonal levels, encompassing the themes and categories listed in Table 1. The genetic findings held personal meaning for parents that influenced their perceptions of self and self in relation to others. News of the inherited defect had a ripple effect on parents’ interactions with extended family members and sometimes beyond the family. A family-systems framework captured this notion that families are comprised of interconnected subsystems, e.g., the individual parent, couple unit, child-sibling unit, grandparent unit, and parents’ siblings units (Friedman, Bowden, & Jones, 2003; White & Klein, 2008). In a previous study, an abnormal NBS result was associated with added stress to the parental subsystem already in a state of disequilibrium following the birth of their infant (Tluczek, Koscik, et al., 2005). Results from the current study built on the earlier findings to show how the genetic results affected various family subsystems. Although a systems theory was useful for explaining family dynamics, it tends to be mechanistic and devoid of the affective quality of the family interactions found in this study. Therefore, we adopted a relational family systems perspective to conceptualize the results from this study.

Intrapersonal Consequences

Parents’ cognitive understandings of test results combined with personal experiences shaped the meanings they attributed to test results. Learning that he or she was also a CF carrier and therefore unknowingly contributed to the child’s genetic status also affected how some parents thought about themselves, particularly in relation to their child. These intrapersonal processes were pivotal to the larger family system because parents acted as the communication center controlling the flow of genetic information to other family members.

Understanding and beliefs about test results

Parental understanding was divided into two content areas: the diagnostic sweat test results and the genetics of CF. All parents reportedly understood that their infants’ sweat test results were normal and their infants were CF carriers. Most believed that the presence of one CF mutation would not cause CF symptoms. For most, this perspective remained stable between the first interview and the 12-month interview. Two couples showed a shift in their thinking between data points. In one case, the child’s frequent respiratory illnesses gave rise to parental concerns that the sweat test results were mistaken and their child actually had CF. Another couple wondered if over time the gene could transform to cause illness. The first exemplar below illustrates typical parent descriptions of their understanding about their child’s sweat test results, and the second two demonstrate shifting perceptions:

And he’s a carrier and he’s going to be healthy.

It seems that this whole year has been nothing but problems with his breathing [said by first parent]. He had a lot of digestive problems. The only thing I’m worried about is maybe, ‘cause they had a lot of people they were testing that day, if maybe they got them [test results] mixed up [added by other parent].

As of right now, it [child’s carrier status] doesn’t mean anything. But, you know, there’s always that slim, slim chance that somewhere down the road . . . something in the human biology where things may change, where just being a carrier could also [change; said by first parent]. Mutate into maybe having it [added by other parent].

The autosomal recessive nature of CF was confusing to some parents (7 mothers and 10 fathers in 13 families). There was a tendency for parents to over- or underestimate the risk of two carriers conceiving a child affected with CF, think that a carrier and noncarrier could have a child with CF, believe that their child’s CF carrier status meant that only one parent was a CF carrier, conclude that one cannot have a child with CF without a family history of the condition, and believe that having older healthy children with a different partner was evidence that she or he did not pass the defective gene onto the child. West and Bramwell (2006) used findings from cognitive psychology research to explain why many individuals have difficulty understanding genetic risk probability. Most people do not consciously calculate the prospects of adverse events occurring in their daily lives. Therefore, when presented with test results consisting of statistical estimates, they tend to use “representativeness” reasoning whereby they simplify the results by placing themselves in one of two categories, e.g., all/high or none/low risk. Similarly, Cameron, Sherman, Marteau, and Brown (2009) found that people have a propensity for dividing risk into categories of low, moderate, or high. The following quotes illustrate this reductionist reasoning:

We were feeling okay because we knew our family history and knew of no one that had it.

We understand that if we were both carriers, it’s higher, and if one of us was we had a 1 in 4 chance; both carriers it’s 50% chance [of child having CF].

Some parents (4 mothers and 4 fathers in 6 families) also misconstrued the implications of having one defective CFTR. For example, they thought that the presence of one defective gene can cause miscarriages, birth defects, male sterility, asthma, digestive problems, and pancreatitis. One parent assumed that she was a carrier because she found salt beads on her face when she perspired. Parents also speculated that smoking or alcohol consumption might be responsible for the mutated CFTR. These misconceptions raise concerns about the accuracy of information these parents, as the primary source of information, might share with their children and other family members:

The other boys have asthma, so that’s what I’m attributing to it [CF gene] is maybe it’s asthma, on that line. So it’s crossed my mind, is this [gene] causing something?

I’ve smoked. Maybe that could be a cause of the CF; I don’t know.

Smith, Michie, Stephenson, and Quarrell (2002) found that lay beliefs about genetics embrace a variety of informational sources and approaches to reasoning. People commonly compare their personal characteristics or physical signs with the symptoms profile of a particular condition and draw conclusions about whether or not they possess a particular gene. Given the wide range of symptoms associated with CF, it is not surprising that individuals who learn about the presence of a CF mutation in a family member might deduce that they, too, possess the same gene and, in the absence of other explanations for particular symptoms, conclude that the CF mutation is responsible for their health problems.

Personal Meaning

Remembering the NBS experience

Mothers (n = 11) tended to think about their NBS experience more often than fathers (n = 4). These memories were commonly roused by pregnancies or births among friends or relatives. Some women used their newly acquired knowledge of NBS to educate their peers. Occasionally, a report about CF in the media prompted recollections. The infant’s first birthday also elicited thoughts of events surrounding the child’s birth that were intimately connected with NBS. The emotional tone of reminiscences suggested feelings of relief and gratitude that their children did not have CF. The frequency of thoughts about NBS reportedly decreased over time. Holditch-Davis, Bartlett, Blickman, and Miles (2003) identified a similar phenomenon among mothers of 6-month-old infants who had been born prematurely. Remembrances precipitated by contextual triggers were part of a constellation of posttraumatic stress symptoms that included reexperiencing, avoidance, and heightened arousal. Parents in our sample identified environmental stimuli for their memories similar to those described by Holditch-Davis et al. (2003); However, the parents in our study did not report the intense negative affect (e.g., depressive feelings) described by the mothers of the premature infants (Holditch-Davis et al., 2003). The following exemplars illustrate the affective tenor of parents’ recollections reported in our study:

I used to think about it a lot, but now it’s getting to the point I don’t think about it that much. But a lot of our friends are expecting babies, and whenever they talk about somebody expecting, I think about what we went through.

When I saw this story on the news on newborn screening I thought about it [NBS].

There are several possible explanations for differences between our findings and those of Holditch-Davis et al. (2003). Although abnormal NBS results represent a medical intrusion into the normative neonatal period when parents are just getting acquainted with their infants, it is a finite event, requires no separation of infant from parent, and most infants remain healthy after the event. By contrast, premature infants often require prolonged hospitalizations, invasive medical interventions, separation from parents, and ongoing treatment for long-term health problems.

Feeling guilt for passing the defective gene to the child

Several participants (6 mothers and 3 fathers in 8 families) described a sense of guilt for passing a potentially illness-producing gene to their child. Some also seemed to feel responsible for the abnormal NBS and the resulting psychological turmoil that it caused their respective family. On a cognitive level, these parents recognized that they had no control over the genetic transmission; still, they described a having sense of culpability on an emotional level. In one case the guilt extended to a maternal grandmother. Some eased their guilt by reasoning that they had healthy lives as carriers and hoped that their children could do so as well. Similar findings of parental feelings of guilt have been documented in studies of predictive genetic testing for diabetes (Shepherd, Hattersley, & Sparkes, 2000) and breast or ovarian cancer (Hamilton, Williams, Skirton, & Bowers, 2009). Although this parental response appears to be benign, one wonders whether this sense of guilt influences parents’ self-perceptions in ways that impact the quality of their parenting and interactions with the child, e.g., leniency in limit setting:

Oh, huge guilt. I just feel really guilty to find out that I’m a carrier of cystic fibrosis, was just something that I’d never thought, of course. Being a carrier hasn’t affected my health or me in any way until now. But just, I feel bad. … Just that everything that our family had to experience and endure and go through was because of a gene that I passed on and that now he is a carrier also.

In the beginning, you felt guilty, but I mean, there’s really nothing you can do about it. So I just finally got over it, I guess. I mean, I’ve lived this long and I’m perfectly fine as far as I can tell, so I don’t see anything else changing.

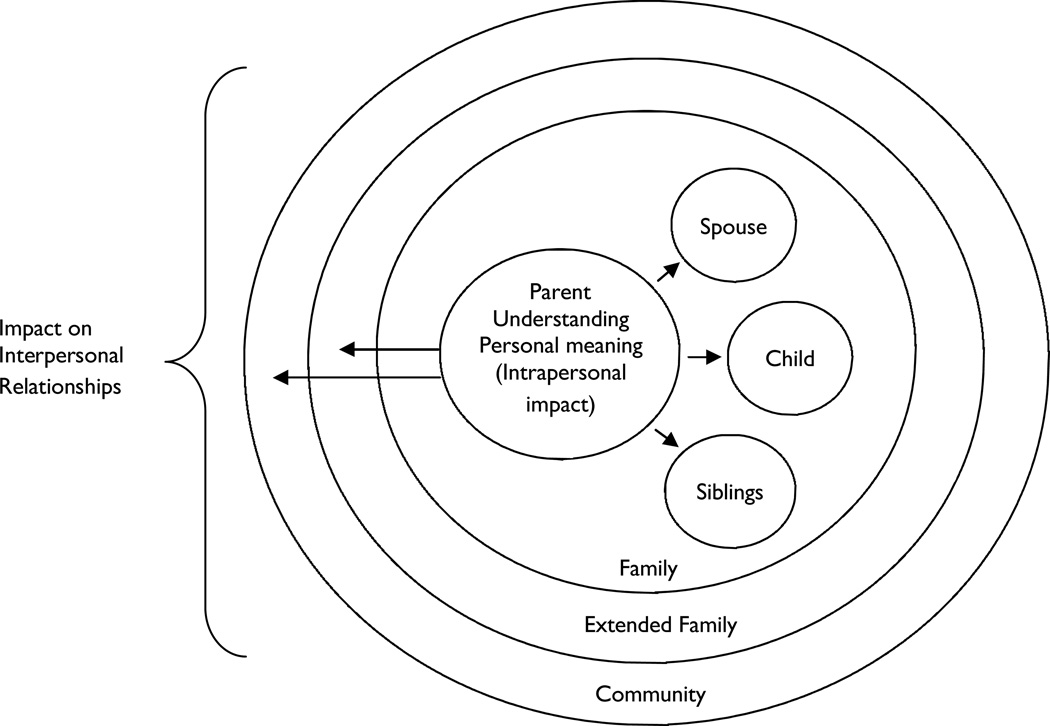

Interpersonal Consequences

D’Agincourt-Canning (2006) used the term familial–relational self to describe how women contemplating genetic testing for breast or ovarian cancer consider the value of such information for other family members before making personal decisions about whether to obtain testing. We applied this concept to our data to conceptualize parents as social beings within multiple concentric relational contexts of immediate family, extended family, and community. Relational proximity seemed to determine the degree of influence; thus, parents’ attentions largely focused on their children and spouses. As illustrated in Figure 2, the structure is similar to Bronfenbrenner’s ecosystem theory of multiple embedded contexts, e.g., microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem that influence child development (Miller, 2002). However, in our model, parents are at the center because they receive the initial genetic information, experience the most acute impact of the results, and initiate the dissemination of the NBS-related information. The direction of influence in our model primarily proceeds from the pivotal center and ripples outward to other subsystems, and therefore differs from the bidirectional influence conceptualized in the ecosystem model.

Figure 2.

Relational family system model: psychosocial consequences of false-positive newborn screen for Cystic Fibrosis

Parent–Child Relationship

Wondering about the accuracy of the sweat test

By 12 months, most parents seemed confident about their children’s good health. Several parents (7 mothers and 4 fathers of 9 children) expressed some doubt about the accuracy of the diagnostic sweat test when their children developed respiratory illnesses. Some reassured themselves that the test results were accurate; others became vigilant for signs of additional respiratory problems. For most, the vigilance diminished over time; however, one couple remained highly skeptical about the test results and believed that their child had CF. The latter findings were very similar to the Holditch-Davis et al. study (2003) in which parents of premature infants reported hypervigilance for health problems in their children. The following quotes illustrate parental wondering about test accuracy:

I just thought that he was sick and I was like, “Oh is he going to be sick forever?” … I know he wasn’t going to be sick because he was a carrier but, maybe the test is wrong.

When she had pneumonia, my first thought was back to the CF.

Although wondering about the test’s accuracy might be considered an intrapersonal process, we classified it as interpersonal because of the potential effects on parent’s interactions with the child. If such perceptions about the child’s vulnerability persist and produce overprotective parenting, the quality of the parent–child relationship could be adversely affected (Green & Solnit, 1964).

Wondering about the future

As parents considered the future, some (6 mothers and 3 fathers) wondered how being a CF carrier might affect their children as they entered their reproductive years, when this knowledge would become relevant. Parents contemplated how and when they might inform their children about their carrier status. A few parents expressed concern about the potential stigmatizing effects of being a CF carrier and its impact on his or her relationship with a prospective partner and their plans for a family:

I think, people, probably the general public has a hard time understanding being a carrier is not a stigma.

I think it would be a good idea for us, at some point down the line, to talk to her about it [being a CF carrier] because if she ends up with a partner that also is a carrier, she’s going to want to know and discuss it with whomever that would be.

We were talking about when would we tell her. Like, when she was engaged and married? It would almost be too late. If she really wanted to know, I feel like we want to tell her but I can’t image, I can’t really imagine that point in our life yet.

Other Children and Parents’ Siblings

Wondering if other family members have CF or are carriers

As parents considered the implications of CF genetics, some imagined multiple scenarios for themselves or other relatives. Some parents (2 mothers and 1 father in 3 families) wondered if their older children, who had respiratory problems or frequent illnesses, might have CF. Another parent expressed concerns that an adult relative who had been treated for asthma might in fact have CF, because the genetic counselor reportedly said that the CF mutation found in the infant’s NBS was associated with a mild form of CF and asthma-like symptoms. Another mother reported concern that an older child might be an undetected carrier because the child was born in a state that did not perform NBS for CF. Three parents also speculated that they might have CF; two had been diagnosed with asthma:

I want to get him [older child] sweat tested to make sure that he doesn’t have it because of the fact that he was so sick, and he was in a hospital all the time and they never said they tested him in the hospital during the screening. … I want to get him tested for CF to see if he has it.

They said that 1 in 25 Europeans are carriers, and mainly Northern European, and we’re both of Northern European descent so I was thinking, well, that’s not so good. … A lot of people aren’t even diagnosed with it until later on in life, and it’s usually as a result of respiratory problems so I thought, well, maybe my asthma is actually mild cystic fibrosis because its mucus in the lungs.

Spousal Relationship

Gaining new perspectives and strengthening relationships

The NBS experience affected the spousal subsystem by engendering a sense of emotional closeness. Parents (8 mothers and 5 fathers in 10 families) explained how their initial shared worry combined with mutual emotional support strengthened couples’ relationships. The encouragement received from extended family members also enhanced filial bonds. They described how the “traumatic” experience of learning that their infants might have a life-threatening illness, followed by the relief that their children did not have the condition, offered parents a new perspective about their lives. Parents reportedly had an increased appreciation for their children’s good health. Some explained that the sleepless nights and other adjustments to parenting a newborn were dwarfed by thoughts of the daunting challenges faced by parents of infants diagnosed with CF:

I think it almost brings you closer just going through that experience because you’re kind of scared and the people that it’s going to affect are family. So you kind of come together and stay pretty close.

I probably was able to cherish moments more, you know what I mean, just little simple things, just sitting and just hanging out. You start to think, well, if this is going to affect how long he’s going to be alive, then you start thinking that every moment is a lot more important than it was before. … You take notice of things.

Questioning paternity

There was one family in which the NBS results produced negative consequences for the spousal relationship. A father’s misconceptions about CF genetics led him to question his paternity of the child identified as a CF carrier. Fortunately, this misunderstanding was reportedly resolved by the 12-month visit. This example illustrates the profound impact that genetic information can have on family relationships. In this case, the problem arose from a knowledge deficit; however, the genetic testing used for CF NBS can incidentally lead to the identification of nonpaternity that if communicated to the couple could threaten their relationship as well as the man’s relationship with the child. Turney (2005) noted that the application of genetic technology to health care has “medicalized” fatherhood by emphasizing the biological role of paternity over the social role of parenthood. The author also acknowledged the ethical dilemma faced by providers regarding the disclosure of such information to parents seeking genetic testing. This dilemma is amplified with NBS because the findings are the product of unsolicited state-mandated genetic testing.

Extended Family Relationships

Finger pointing in search of the genetic source

The practice of finger pointing (1 mother and 6 fathers in 7 families) represented attempts to find the genetic source in family pedigrees rather than lay blame. The absence of CF in the family led some extended family members to “point the finger” at the child’s “other side” of the family. For the most part, parents described this banter about the “mutant” as a playful jest among relatives. Some other parents (2 fathers and 2 mothers in 4 families) said that they searched their family histories for evidence of the defective CF gene, or they tried to calculate how many carriers there might be in their families. Thus, the impact of the genetic results spread to family subsystems proximal and distal to the nuclear family:

His family was like, “No one in our family has that.” And then my dad’s like, “No one in our family has that.”

If you kind of think back on all of your family members and relatives and stuff, and even my side and all the family, we both sat there and said, really can’t think of anybody’s obviously that had it. … So it’s like, okay, how many family members on either side are possible carriers?

Sharing genetic information with extended family: Burden vs. opportunity

The familial–relational self was eloquently illustrated in parents’ descriptions of their sense of moral responsibility to communicate genetic information to other relatives, particularly child-bearing-aged siblings. The quality of relationships largely determined whether parents viewed this task as an opportunity or burden. Most parents viewed the process as an opportunity (5 mothers and 2 fathers in 6 families), but others felt burdened by the obligation (3 mothers and 2 fathers). Reasons for informing other family members included (a) providing them opportunities to obtain genetic testing, (b) preventing shock if their infants’ NBS results were abnormal for CF, and (c) having children tested for CF if they were born in a state that did not screen neonates for CF:

A definite positive came out of the whole thing. We learned more about it. We can educate our families once we find out which one of us carries it and let them know that there’s a chance this may happen to you. If it does, don’t freak out. Here’s what to expect.

It’s vital information for both of our families because if they have kids or whatever, down the line, I think that would be important that everybody would know and know it’s in our genetic line. Because I was really shocked that it even came up. I never knew it was a hereditary thing. That really shocked me.

I told my sister because she has children and lives in [other state]. I didn’t know if they do the testing in [other state], so I told her to probably have them tested.

Parents who felt burdened by the need to share genetic information with extended family members explained that their attempts to communicate this information with relatives aggravated already strained or estranged relationships. These parents struggled with deciding how and when to initiate such conversations with their relatives. This dilemma was particularly challenging for parents who had been adopted. When asked if they felt burdened by needing to inform family members, the typical response was, “Yes, definitely.”Coates et al. (2007) reported that parents of infants diagnosed with CF cited similar reasons for sharing genetic information with relatives. They also identified physical and relational distance as obstacles to communication. Hamilton and colleagues (2009) found a similar mix of positive and negative changes in family relationships associated with shared genetic information about breast and ovarian cancer.

Relationship With Community

Feeling empathy for parents of children with CF

The knowledge of the CF mutation in their family created a sense of belonging to the larger community of families affected by CF. Parents (2 mothers and 2 fathers in 4 families) expressed a deep sense of empathy for families whose infants were diagnosed with CF as a result of NBS. They became more attuned to CF-related events in their communities or stories in the popular media. Several demonstrated their compassion and sense of connectedness with the CF community by becoming involved in the CF Foundation’s fundraising events to support CF research and patient care. This finding illustrated the ripple effect of an abnormal NBS extending beyond the family to the community:

And then once they tell you that there’s a possibility, then you just understand what the other families go through that have a child that has it [CF].

I think I’m much more aware of all the cystic fibrosis things that you see on TV [television] and in the newspaper, and it just brings you back to, “Oh my gosh, this could have been us.”

Supporting CF NBS

Parents’ support for CF NBS was another example of their relationship with the CF community. Most parents (32 mothers and 30 fathers) reported support for NBS for CF, citing multiple reasons, including that NBS (a) affords early treatment for affected children, (b) prevents multiple medical encounters in search of a diagnosis, (c) informs parents about their child’s carrier status, (d) provides parents opportunities to have carrier testing, (e) might rule out a CF diagnosis for the child in the future, and (f) can document the natural history of CF carriers’ health. Additionally, some parents explained that asymptomatic infants with CF might benefit from a neonatal diagnosis because their parents could learn the signs associated with the condition and monitor their children accordingly. A few respondents thought that an early diagnosis might help parents psychologically prepare for the onset of symptoms. Another 11 parents (6 mothers and 5 fathers) offered conditional or ambivalent support for CF NBS. These parents questioned the evidence for health benefits of a neonatal diagnosis, particularly in light of the high rate of false-positive results and associated psychological distress. Finally, there were 9 who did not respond, but no parent totally opposed NBS for CF.

Examples of support for CF NBS.

Because if there is a problem, you can catch it early on. I mean, if you know right after they’re born, they can start treatments if they need to or maybe they can fix the problem ahead of time.

Even though they may not develop symptoms for some time down the road, if they do test positive, it allows the parents and family members to prepare mentally for what is impending.

Now we do have the information for when he gets older and gets married and wants to have children. … At least he won’t have to go through this. He’ll have that knowledge up front.

Conditional or ambivalent support for CF NBS.

I’m not totally convinced, and, and I probably could be, that early intervention [for CF] is necessary. If it’s been proven then I think it’s a good thing. If it doesn’t make a difference then I’m not sure.

Yes, I wish that there was a way to have the screen more accurate, the initial screen to narrow it down real fast. It just affects too many people’s lives and emotions, and it’s not accurate enough. I think if they’re going to do it they should get to where, heaven forbid, you test positive for the screen, I would rather have the numbers be down to where, it’s one in four or whatever so that you’re not affecting so many people.

One of the first thoughts was, well, it came back that he might have it [CF], and I just remember thinking, well he might have had a lot of things and did we have to go through all this to figure out that he didn’t have a whole bunch of other stuff like cancer and AIDS and all that stuff? … The way that it turned out for us was it didn’t matter, but it could have mattered, so I can see why it would be good so I’m kind of both ways with it—I’m both ways with it.

Demographic Predictors of Psychosocial Outcomes

Using exact logits modeling, we found that “remembering NBS experience” was significantly negatively influenced by age (p = 0.04) and significantly positively influenced by education (p = 0.01). Younger and more highly educated parents were more likely to report thinking about the NBS experience than their older and less-educated counterparts. No other significant relationships between demographic characteristics and psychosocial outcomes were identified.

Discussion

The relational family system framework derived from this study facilitated our understanding of intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics associated with abnormal NBS results that involved genetic testing. These findings were consistent with those reported in an article on an earlier qualitative study that recounted parents’ perspectives about their infants’ equivocal diagnostic results from CF NBS (Tluczek et al, in press). A subset of parents in each study described lingering concerns about the health implications of the genetic results and wondered about the presence of the defective gene in their other family members. The results of the current study build on previous research by elaborating on previously undocumented psychosocial consequences of false-positive results and the impact on the larger family system.

It was encouraging that all of the families in this cohort understood that their infants had normal sweat test results and that their children were CF carriers. Nevertheless, it was concerning that some parents held misconceptions about autosomal recessive genetics and the implications of being a CF carrier. Parents’ inclinations to over or underestimate genetic risk echoed findings from other research (Cameron et al., 2009; West & Bramwell, 2006). There is clearly a need to identify the most effective counseling methods to improve parents’ understanding of genetic information.

NBS for CF and the related follow-up diagnostic results appeared to be unlike other types of medical results that are quickly shelved in the remote recesses of memory. Remembrances of the NBS experience remained readily retrievable to the consciousness of many parents. Perhaps younger, more educated parents were more prone to these recollections than their older, less educated counterparts because the former group had greater access to electronic media with news about NBS or CF that might stir up memories. Although the retrieval of NBS memories occurred infrequently, the content of the recollections suggested meanings that were poignantly personal. Sometimes reflections drifted back to the time of the actual NBS and how sadly different their lives could have been if their child had been diagnosed with CF. Other thoughts were associated with feeling guilty for transmitting a defective gene to their progeny. Most parents described a tremendous sense of gratitude for their child’s good health. Although the NBS experience was in the past, for most parents a year later it had not been forgotten. These findings raise questions as to whether such memories represent a form of posttraumatic stress, as previously documented by Holditch-Davis and colleagues (2003), and warrant further study.

Findings from this study reveal several interpersonal outcomes of false-positive NBS for CF that were not previously detailed in the literature. Parents expressed concerns about how the genetic information might affect their children’s lives in the future. Some speculated that they or other family members might have CF. Extended relatives engaged in finger pointing about the source of the defective gene. Parents described an affinity for parents of children with CF. Thus, the ripple effects of the genetic results were felt at multiple levels within the family system and motivated some to embrace the CF community as part of this system.

The issue of questioned paternity underscored the importance of including both parents in genetic counseling at the time of the diagnostic sweat test. Primary care providers, who inform parents about the initial NBS results, might encourage both parents to attend the counseling session. A family-centered approach to counseling could include anticipatory guidance about the issues described in this article and a follow-up plan to address parental concerns.

Studies examining the consequences of false-positive NBS results tend to be focused on the presence or absence of particular risks identified by the investigator, with relatively little attention paid to the benefits. By contrast, the interviewing method used in this study allowed parents to share the full spectrum of consequences. Parents were able to draw on personal strengths to overcome their initial distress, appreciate their children’s good health, and feel empathy for families who have children with serious health conditions. The endorsement of NBS for CF by study participants offers evidence that most parents are willing to endure the psychosocial risks associated with abnormal NBS results so that families with infants who have CF might garner the health benefits of an early diagnosis.

Although a sample of 87 parents is relatively large for a qualitative study, the use of a convenience sample could have produced selection bias. Parents with strong feelings about NBS might have been more likely to participate. Despite this limitation, the findings offer clinicians guidance for supporting parents by recognizing that abnormal genetic NBS results affect the entire family system.

Conclusion

Abnormal NBS results that involve genetic testing can have psychosocial repercussions that affect entire families. These findings merit additional investigation of long-term psychosocial sequelae for false-positive results, interventions to reduce adverse iatrogenic outcomes, and the relevance of the relational family system framework to other genetic testing programs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the parents who participated in this project and the research teams from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Marshfield Clinics, Marshfield, and Gundersen-Lutheran, La Crosse, Wisconsin.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This project was funded by the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (K23 HD42098), and the School of Nursing Research Committee of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Additional editorial support was provided through the Clinical and Translational Science Award program (1UL1RR025011) of the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Baroni MA, Anderson YE, Mischler E. Cystic fibrosis newborn screening: Impact of early screening results on parenting stress. Pediatric Nursing. 1997;23(2):143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron LD, Sherman KA, Marteau TM, Brown PM. Impact of genetic risk information and type of disease on perceived risk, anticipated affect, and expected consequences of genetic tests. Health Psychology. 2009;28(3):307–316. doi: 10.1037/a0013947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciske DJ, Haavisto A, Laxova A, Zeng L, Rock M, Farrell PM. Genetic counseling and neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis: An assessment of the communication process. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):699–705. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates N, Gregory M, Skirton H, Gaff C, Patch C, Clarke A, et al. Family communication about cystic fibrosis from the mother’s perspective: An exploratory study. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2007;12:619–634. [Google Scholar]

- d’Agincourt-Canning L. Genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: Responsibility and choice. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:97–118. doi: 10.1177/1049732305284002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff A, Brownlee K. Psychosocial aspects of newborn screening programs for cystic fibrosis. Children's Health Care. 2008;37(1):21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell PM, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Shen G, Koscik RE, Bruns WT, et al. Nutritional benefits of neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:963–969. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell PM, Kosorok MR, Rock MJ, Laxova A, Zeng L, Lai HC, et al. Early diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through neonatal screening prevents severe malnutrition and improves long-term growth. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, Accurso FJ, Castellani C, Cutting GR, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;153(2):S4–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MM, Bowden VR, Jones EG, editors. Family nursing: Research, theory, and practice. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti R New York State Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Consortium. Elevated IRT levels in African-American infants: Implications for newborn screening in an ethnically diverse population. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2008;43:638–641. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Solnit AJ. Reactions to the threatened loss of a child: A vulnerable child syndrome. Pediatric management of the dying child, Part III. Pediatrics. 1964;34:58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton R, Williams JK, Skirton H, Bowers BJ. Living with genetic test results for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2009;41:276–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holditch-Davis D, Bartlett TR, Blickman AL, Miles MS. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers of premature infants. Journal of Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing. 2003;32(2):161–171. doi: 10.1177/0884217503252035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S, Curnow L, Ross M, Massie J. Parental attitudes to the identification of their infants as carriers of cystic fibrosis by newborn screening. Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health. 2006;42:533–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. Understanding and validity in qualitative research. Harvard Educational Review. 1992;62(3):279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Miller PH. Theories of developmental psychology. 4th ed. New York: Worth; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mischler EH, Wilfond BS, Fost N, Laxova A, Reiser C, Sauer CM, et al. Cystic fibrosis newborn screening: Impact on reproductive behavior and implications for genetic counseling. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1):44–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran J, Quirk K, Duff AJA, Brownlee KG. Newborn screening for CF in a regional paediatric centre: The psychosocial effects of false-positive IRT results on parents. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2007;6:250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newborn Screening Task Force. Serving the family from birth to the medical home. Newborn screening: A blueprint for the future—A call for a national agenda on state newborn screening programs. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2, Pt 2):389–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons EP, Clarke AJ, Bradley DM. Implications of carrier identification in newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2003;88:F467–F471. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.6.F467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock MJ, Hoffman G, Laessig RH, Kopish GJ, Litsheim TJ, Farrell PM. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis in Wisconsin: Nine-year experience with routine trypsinogen/DNA testing. Journal of Pediatrics. 2005;147(Suppl. 3):S73–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp JK, Rock MJ. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2008;35:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s12016-008-8082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd M, Hattersley AT, Sparkes AC. Predictive genetic testing in diabetes: A case of multiple perspectives. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10:242–259. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Michie S, Stephenson M, Quarrell O. Risk perception and decision-making process in candidates for genetic testing for Huntington’s disease: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7(2):131–144. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007002398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tluczek A, Clark R, Koscik RL, Farrell PM. Mother-infant relationships in the context of neonatal CF diagnosis: Preliminary findings. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2005;28(Suppl):179–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tluczek A, Koscik RL, Farrell PM, Rock MJ. Psychosocial risk associated with newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: Parents’ experience while awaiting the sweat test appointment. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1692–1703. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tluczek A, Koscik RL, Modaff P, Pfeil D, Rock MJ, Farrell PM, et al. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: Parents’ preferences regarding counseling at the time of infants’ sweat test. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2006;15:277–291. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tluczek A, Mckechnie AC, Lynam PA. When the cystic fibrosis label does not fit: A modified uncertainty theory. Qualitative Health Research. doi: 10.1177/1049732309356285. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turney L. The incidental discovery of nonpaternity through genetic carrier screening: An exploration of lay attitudes. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:620–634. doi: 10.1177/1049732304273880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West H, Bramwell R. Do maternal screening tests provide psychologically meaningful results? Cognitive psychology in an applied setting. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2006;24(1):61–69. [Google Scholar]

- White JM, Klein DM. Family theories. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]