Abstract

The opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus reproduces asexually by forming a massive number of mitospores called conidia. In this study, we characterize the upstream developmental regulator A. fumigatus flbB (AfuflbB). Northern blotting and cDNA analyses reveal that AfuflbB produces two transcripts predicted to encode two basic leucine zipper domain (bZIP) polypeptides, AfuFlbBβ (420 amino acids [aa]) and AfuFlbBα (390 aa). The deletion of AfuflbB results in delayed/reduced sporulation, precocious cell death, the lack of conidiophore development in liquid submerged culture, altered expression of AfubrlA and AfuabaA, and blocked production of gliotoxin. While introduction of the wild-type (WT) AfuflbB allele fully complemented these defects, disruption of the ATG start codon for either one of the AfuFlbB polypeptides leads to a partial complementation, indicating the need of both polypeptides for WT levels of asexual development and gliotoxin biogenesis. Consistent with this, Aspergillus nidulans flbB+ encoding one polypeptide (426 aa) partially complements the AfuflbB null mutation. The presence of 0.6 M KCl in liquid submerged culture suppresses the defects caused by the lack of one, but not both, of the AfuFlbB polypeptides, suggesting a genetic prerequisite for AfuFlbB in A. fumigatus development. Finally, Northern blot analyses reveal that both AfuflbB and AfuflbE are necessary for expression of AfuflbD, suggesting that FlbD functions downstream of FlbB/FlbE in aspergilli.

The opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus (reviewed in reference 9) propagates in the environment by producing a massive number of mitotic spores called conidia (19). Under appropriate conditions, the conidium germinates and undergoes vegetative growth that leads to the formation of a network of undifferentiated interconnected hyphae known as the mycelium. After a certain period of hyphal proliferation, in response to appropriate cues (e.g., exposure to air, nutrient deprivation, or osmotic stress) some of the vegetative cells initiate asexual development (conidiation) and go through a series of morphological changes, which result in the formation of conidiophores consisting of foot cell, stalk, vesicle, phialides, and (up to 50,000) conidia (19, 26). Conidia (2 to 3 μm in diameter) are then released into the environment and are small enough to reach the alveoli after being inhaled by humans (31). In immunocompromised hosts the conidia are able to germinate into invasive hyphae, which penetrate the vasculature and migrate to distal sites (reviewed in reference 26).

We have been investigating the mechanisms underlying asexual development and gliotoxin biosynthesis in A. fumigatus, primarily focusing on understanding the functions of a number of developmental regulators identified in the model fungus Aspergillus nidulans (21, 30, 40). A key step for conidiation in A. nidulans is the activation of brlA encoding a C2H2 zinc finger transcription factor (TF) (1). Together with abaA and wetA, these three elements define a central regulatory pathway that coordinates the temporal and spatial control of sporulation-specific gene expression during asexual development in A. nidulans (2, 4, 22, 23). Our previous studies have revealed that the roles of BrlA, AbaA, and WetA in developmental regulation are essentially identical in two Aspergillus species (20; also L. Tao and J.-H. Yu, unpublished data).

Identification and characterization of six upstream genes (fluG, flbA, flbB, flbC, flbD, and flbE) required for proper expression of brlA in A. nidulans have illuminated genetic regulatory cascades leading to the activation of asexual development (2, 23, 33). Among these, flbB, flbC, flbD, and flbE were defined by the fluffy delayed-conidiation mutants (33). FlbB, FlbC, and FlbD are putative TFs containing a basic leucine zipper domain (bZIP), two C2H2 zinc fingers, and a c-Myb-DNA binding domain, respectively, and have been shown to act on the activation of brlA expression (10, 11, 14, 16, 32). Recent studies demonstrated that the bZIP TF FlbB is necessary for the expression of flbD and that FlbB and FlbD activate brlA in a supportive manner (14). The A. nidulans flbE (AniflbE) gene is predicted to encode a 201-amino-acid (aa)-long polypeptide with two conserved yet uncharacterized domains, and it was demonstrated that FlbE and FlbB are functionally interdependent, physically interact in vivo, and colocalize at the hyphal tip in A. nidulans (13).

Our recent studies have demonstrated that A. fumigatus FlbE (AfuFlbE) is crucial for proper conidiation and is functionally conserved in two aspergilli (17). In this study, we characterize AfuflbB and present evidence that FlbB is vital for A. fumigatus morphological development and gliotoxin production. Unlike flbB in A. nidulans, AfuflbB produces two transcripts predicted to encode two bZIP polypeptides, AfuFlbBβ (420 aa) and AfuFlbBα (390 aa). The deletion of AfuflbB results in multiple defects in development, cell viability, and gliotoxin biosynthesis. A series of complementation studies indicate that both AfuFlbB polypeptides are necessary for proper asexual and chemical development. Supporting this, A. nidulans flbB+ encoding one polypeptide (426 aa) only partially complements the AfuflbB null mutation. High KCl concentration suppresses the defects caused by the absence of one, but not both, of the AfuFlbB polypeptides, suggesting a genetic prerequisite for AfuFlbB in A. fumigatus conidiation and gliotoxin production. Finally, we show that both AfuflbB and AfuflbE are necessary for expression of AfuflbD, and we present a model depicting developmental regulation in A. fumigatus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and culture conditions.

Aspergillus strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Except for the A. fumigatus auxotrophic strains, all fungal strains were routinely grown on solid or liquid glucose minimal medium (MMG) with 0.1% (or 0.5%) yeast extract (YE) at 37°C, as previously described (20). For uridine-uracil and arginine auxotrophic mutants (strains AF293.1 and AF293.6) (34), the medium was supplemented with 5 mM uridine, 10 mM uracil, and (for AF293.6) 0.1% arginine. Escherichia coli DH5α was used for routine cloning of constructs and cultured in LB broth, Miller (Novagen, CA), at 37°C and supplemented with appropriate antibiotics.

Table 1.

Aspergillus strains used in this study

| Strain name | Relevant genotype | Reference and/or sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| AF293 | A. fumigatus wild type | 5 |

| AF293.1 | AfupyrG1 | 34 |

| AF293.6 | AfupyrG1; AfuargB1 | 34 |

| A1176 | AfupyrG1; ΔAfubrlA::AfupyrG+ | 20; FGSC |

| TKSS1.01 | AfupyrG1 ΔAfuflbB::AnipyrG+ | This study |

| TPX2.01 | AfupyrG1 ΔAfuflbB::AniargB+; AfuargB1 | This study |

| TPX5.10 | AfupyrG1::AfuflbB(p)::AfuflbB::AfuflbB(t)::AfupyrG+ ΔAfuflbB::AniargB+; AfuargB1 | This study |

| TPX6.01 | AfupyrG1::AfuflbB(p)::AfuflbB::AnitrpC(t)::AfupyrG+ ΔAfuflbB::AniargB+; AfuargB1 | This study |

| TPX7.06 | AfupyrG1::AfuflbB(p)::AfuflbBβ::AnitrpC(t)::AfupyrG+ ΔAfuflbB::AniargB+; AfuargB1 | This study |

| TPX8.02 | AfupyrG1::AfuflbB(p)::AfuflbBα::AnitrpC(t)::AfupyrG+ ΔAfuflbB::AniargB+; AfuargB1 | This study |

| TPX9.03 | AfupyrG1::AniflbB(p)::AniflbB::AniflbB(t)::AfupyrG+ ΔAfuflbB::AniargB+; AfuargB1 | This study |

| TKSS6.07 | ΔAfuflbE::AnipyrG+; AfupyrG1 | 17 |

| FGSC4 | A. nidulans wild type | FGSC |

Fungal Genetic Stock Center.

For phenotypic analyses of A. fumigatus strains on air-exposed culture, the conidia (∼104) of relevant strains were spotted in 2-μl aliquots on appropriate solid medium and incubated at 37°C for 3 days. Conidia were collected in 0.5% Tween 80 from the entire colony and counted using a hemacytometer. To examine development and secondary metabolite production in liquid submerged culture, spores of relevant strains were inoculated to a final concentration of 106 conidia/ml in 50 ml of liquid MMG with 0.1% YE and incubated at 250 rpm at 37°C for a period of 4 days. The mycelial aggregates of each strain were observed microscopically starting at 6 h of liquid culture and every 6 h thereafter. To check cell viability in liquid submerged culture, the conidia (∼2 × 105/ml) of relevant strains were inoculated in 300 ml of liquid MMG with 0.1% YE in 1-liter flasks and incubated at 37°C at 250 rpm for a period of 6 days. For induction of asexual development and salt stress, the conidia (∼106/ml) of wild-type (WT) and mutant strains were inoculated in 300 ml of liquid MMG with 0.1% YE in 1-liter flasks and incubated at 37°C at 250 rpm for 14 to 18 h (this is the 0-h time point for developmental induction). The mycelium was harvested by filtering through Miracloth (Calbiochem, CA) and transferred either to solid MMG with 0.1% YE and incubated at 37°C for air-exposed asexual developmental induction or to liquid MMG with 0.6 M KCl and cultured at 250 rpm and 37°C for salt stress-induced development. The plates and mycelium pellets of relevant strains were visually and microscopically examined. Samples collected at various time points of the liquid submerged culture and post-asexual developmental induction were squeeze dried and stored at −80°C until subjected to total RNA isolation.

Generation of AfuflbB mutants.

The AfuflbB gene was deleted in A. fumigatus AF293.1 (pyrG1) and AF293.6 (pyrG1; argB1) strains (34) employing double-joint PCR (DJ-PCR) (37). Oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Briefly, approximately 1.4 to 1.7 kb of the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the AfuflbB gene was amplified from A. fumigatus AF293 genomic DNA with the primer pairs oKS31/oKS33 (∼1.74 kb) and oKS34/oKS36 (∼1.63 kb with the AnipyrG tail) and the pairs oKS31/oPX76 (∼1.43 kb) and oPX77/oKS36 (∼1.63 kb with the AniargB tail), respectively. The A. nidulans selective markers were amplified from FGSC4 genomic DNA with the primer pairs oBS8/oBS9 (AnipyrG) and oKH60/oNK105 (AniargB). The 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of AfuflbB were fused to each relevant marker and further amplified by the nested primer pairs oKS32/oKS35 and oPX71/oKS35, yielding the final gene deletion constructs. The gene deletion constructs were introduced into recipient strains AF293.1 and AF293.6, respectively. The ΔAfuflbB mutants (e.g., strains TKSS1.01 and TPX2.01) were isolated and confirmed by PCR, followed by restricted enzyme digestion (37). At least three deletion strains in each case were isolated.

To complement ΔAfuflbB, the wild-type AfuflbB allele (open reading frame [ORF] with 0.73 kb of the 5′ and 1 kb of the 3′ regions) was amplified with the primer pair oPX80/oPX2, digested with PvuII and HindIII, and cloned into pNJ25 (28). The resulting plasmid pPX1 was then introduced into the recipient ΔAfuflbB strain TPX2.01 (ΔAfuflbB::AniargB+; AfupyrG1), where preferentially a single-copy AfuflbB+ gets inserted into the AfupyrG locus. Multiple complemented strains were isolated and confirmed by PCR and Northern blot analyses. Similarly, the AfuflbB ORF with a 0.73-kb 5′ flanking region was amplified using the primer pair oPX80/oPX26, digested, and cloned between PvuII and HindIII sites in pNJ25 to generate plasmid pPX2, carrying the chimeric AfuflbB gene comprised of the AfuflbB native promoter, AfuflbB coding region, and the AnitrpC terminator (35, 36). The resulting plasmid was introduced into the recipient ΔAfuflbB strain TPX2.01, and several strains displaying phenotypes identical to those of AfuflbB+ with the native terminator were isolated and confirmed.

To generate the mutants producing only AfuFlbBβ or AfuFlbBα, the plasmids pPX3 and pPX4 were constructed and introduced into the ΔAfuflbB strain TPX2.01. Briefly, the mutagenic primer pairs oPX101/oPX97 and oPX98/oPX102 and the pairs oPX101/oPX99 and oPX100/oPX102 were used to amplify different parts of AfuflbB, (see Table S1 in the supplemental material, where base mismatches are underlined in the joint parts of each amplicon conferring ATG-to-GCC mutations in each predicted ATG start codon). After separate conventional PCRs, the amplicons with complementary joint tails were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and subjected to fusion reactions. Then, the fused PCR products were amplified using the primer pair oPX80/oPX26, yielding amplicons with 0.73 kb of 5′ flanking sequence with the mutated AfuflbB ORF; the +1 position ATG or +460 position ATG (Met) was replaced with GCC (Ala). The final PCR products were digested and cloned between PvuII and HindIII sites in pNJ25 and sequence verified, resulting in pPX3 and pPX4 carrying the chimeric mutated AfuflbB gene comprised of the AfuflbB native promoter, the AfuFlbB coding region from which only one polypeptide is predicted to be translated, and the AnitrpC terminator. Then, these two plasmids were introduced into the recipient ΔAfuflbB strain TPX2.01 separately. Multiple transformants were isolated and confirmed by PCR. Cross-complemented strains were obtained by introducing the pNJ25-derived plasmid pPX5 carrying AniflbB+ (amplified using primer pair oPX90/oPX104 and cloned between PvuII and XbaI sites in pNJ25) into a ΔAfuflbB strain (TPX2.01).

Nucleic acid isolation and manipulation.

Genomic DNA and total RNA isolation were carried out as described previously (20, 37). Approximately 10 μg (per lane) of total RNA isolated from individual samples was separated by electrophoresis using a 1.1% agarose gel containing 3% formaldehyde and ethidium bromide and blotted onto a Hybond-N membrane (Amersham, NY). The [32P]dCTP-labeled hybridization probes for AfuflbB, AfuflbC, AfuflbD, AfuflbE, AfubrlA, AfuabaA, AfuwetA, AfuvosA, and gliZ were prepared by PCR amplification of individual ORFs from the genomic DNA of AF293 by using specific oligonucleotides (listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material). RNA blots were hybridized with individual probes using modified Church buffer (1 mM EDTA, 0.25 M Na2HPO4·7H2O, 1% hydrolyzed casein, and 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 85% H3PO4) as previously described (39).

Assessment of cell viability.

The Alamar blue (AB) assay was used to evaluate the cell viability by the percent reduction of Alamar blue as described previously (27, 29). Briefly, the amount of Alamar blue cell proliferation indicator (AbD Serotec, NC), equal to 10% of the final volume in the wells, was added into each test well of a 24-well plate (Nunc) containing 1 ml of fresh MMG-0.1% YE and 0.5 ml of individual cultures. After 6 h of incubation at 37°C, the absorbance of each well was measured at 570 and 600 nm. The percent reduction of AB was calculated as described previously (29). In addition, to further assess the levels of apoptotic-like cell death, the hyphal cells were stained with Evans blue as previously described (29). The mycelia of relevant strains grown for certain period were collected and treated with Evans blue staining solution (1% Evans blue [Sigma, St. Louis, MO] in PBS) for 5 min at room temperature, and then excessive dye was washed out with 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times. The samples were analyzed using a bright-field microscope.

Gliotoxin analysis.

Gliotoxin production was analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described previously (3, 28). To examine gliotoxin production in liquid culture, conidia (∼106/ml) from individual strains were inoculated into 50 ml of liquid MMG with 0.1% YE in 250-ml flasks and incubated at 37°C and 250 rpm for 48 h. The liquid cultures of relevant strains were filtered by Miracloth, 50 ml chloroform was added to the filtered liquid medium, and the mixture was agitated at 250 rpm for 30 min on a rotary shaker at room temperature (28). The aqueous layer was removed, and the chloroform extract was then air dried at room temperature and suspended in 200 μl of methanol. Approximately 15 μl of each sample was loaded onto the silica TLC plates containing a fluorescent indicator (Kiesel gel 60; E. Merck, Germany). Gliotoxin standard was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The TLC plates were developed in toluene-ethyl acetate-formic acid (5:4:1, vol/vol/vol). To assess gliotoxin production on solid medium, conidia (∼104) of relevant strains were point inoculated at the center of MMG with 0.5% YE and cultured at 37°C for 72 h. Equal amounts of agar plugs of the center of the colonies were removed and extracted with 15 ml of chloroform and agitated vigorously at 250 rpm overnight (3). The chloroform extracts were air dried and suspended in 200 μl of methanol, and then extracts (45 μl/lane) were loaded and analyzed. Photographs of TLC plates were taken following exposure to UV radiation using a Sony DSC-T70 digital camera.

Microscopy.

The colony photographs were taken using a Sony DSC-T70 digital camera. Photomicrographs were taken using a Carl Zeiss M2 BIO fluorescent microscope with a Carl Zeiss AxioVision digital imaging system installed.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of AfuflbBβ was deposited in GenBank under accession number HM582656.

RESULTS

Identification and analyses of A. fumigatus FlbB.

The putative A. fumigatus FlbB gene was identified by a BLASTP search in the Aspergillus genome database (Broad Institute Aspergillus Comparative Database [http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/aspergillus_group/MultiHome.html]) with A. nidulans FlbB (GenBank accession number CAM35586.1). Among four matches returned, Afu2g14680 shows 65% identity, 77% similarity, and an expected value of 0. Moreover, a conserved bZIP (pfam00170) domain found in A. nidulans FlbB was present at the N terminus (amino acids 35 to 69) of this protein. These results suggest that Afu2g14680 is likely the A. fumigatus homolog of FlbB, and it was designated AfuflbB. Additional reciprocal BLASTP searches using the predicted protein sequence of AfuFlbB against other Aspergillus genomes revealed that the best match is AniFlbB in A. nidulans, with orthologues of AfuFlbB found in other Aspergillus species including Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus clavatus, Aspergillus terreus, and Aspergillus flavus, as reported for AniFlbB (11). Sequence alignments of FlbB demonstrated that FlbB is highly conserved in aspergilli; however, the annotated FlbBs in A. fumigatus and A. clavatus appear to lack 20 to 30 amino acids compared to the sequence of AniFlbB (data not shown).

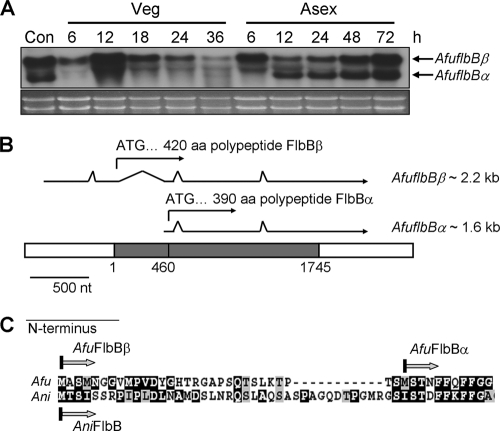

Northern blot analysis of AfuflbB mRNA levels throughout the life cycle of A. fumigatus WT (AF293) revealed that the AfuflbB gene encodes two distinct transcripts of approximately 2.2 and 1.6 kb, which were designated AfuflbBβ and AfuflbBα, respectively (Fig. 1A). The levels of the longer transcript are relatively constant throughout the life cycle, whereas the shorter transcript accumulates specifically along with the progression of asexual sporulation and remains at high levels in conidia. During vegetative growth, the shorter transcript is undetectable, and it begins to accumulate at 12 h post-asexual developmental induction.

Fig. 1.

Summary of AfuflbB. (A) Northern blot showing mRNA levels of AfuflbB throughout the life cycle of A. fumigatus WT (AF293) strain. Con, conidia. The time (hours) of incubation in liquid submerged culture (Veg) and of post-asexual developmental induction (Asex) is shown. Equal loading of total RNA was evaluated by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. A band shown between the two AfuflbB transcripts is due to nonspecific binding of the probe to rRNA. (B) Schematic presentation of a genomic DNA region covering the AfuflbB gene and two transcripts. The AfuflbB ORF (shaded box), transcripts (arrows), and the introns (shown by discontinuity in the arrow) were verified by sequence analysis of AfuflbB cDNA. The start codon (ATG) of AfuFlbBβ is assigned as +1. (C) Alignment of N terminus of FlbB proteins in A. fumigatus (Afu) and A. nidulans (Ani). The predicted N termini (Met) of AfuFlbBβ, AfuFlbBα, and AniFlbB are marked. Note that the 42nd amino acid in A. nidulans FlbB is not methionine but isoleucine. Alignment was done by ClustalW (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/ClustalW.html) and is presented by BOXSHADE, version 3.21 (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html).

To understand the nature of these two transcripts, various regions of AfuflbB cDNAs were amplified from the A. fumigatus AF293 Uni-ZAP cDNA library (25) (kindly provided by G. S. May at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center). Direct sequencing of those PCR amplicons combined with comparison to the genomic sequence of A. fumigatus AF293 led to the identification of two overlapping transcription units with identical 3′ ends (Fig. 1B). The 2.2-kb AfuflbBβ transcription unit contains four introns (positions −220 to −152, +53 to +421, +512 to +574, and +1233 to +1282) (Fig. 1B) and initiates at −589 with the start codon at +1, resulting in a 420-amino-acid polypeptide (accession number HM582656). The 1.6-kb AfuflbBα transcription unit contains two introns (positions +512 to + 574 and +1233 to +1282) (Fig. 1B), initiates at +421 with the first ATG at +460, and is predicted to encode a 390-aa polypeptide, which is essentially identical to AfuFlbBβ except for the first 30 amino acids at the N terminus (Fig. 1C). AfuFlbBα was identical to the predicted protein sequence originally annotated (XP_755800.2). One polypeptide encoded by the AniflbB locus is shown for the comparison (Fig. 1C).

Role of AfuFlbB in asexual development.

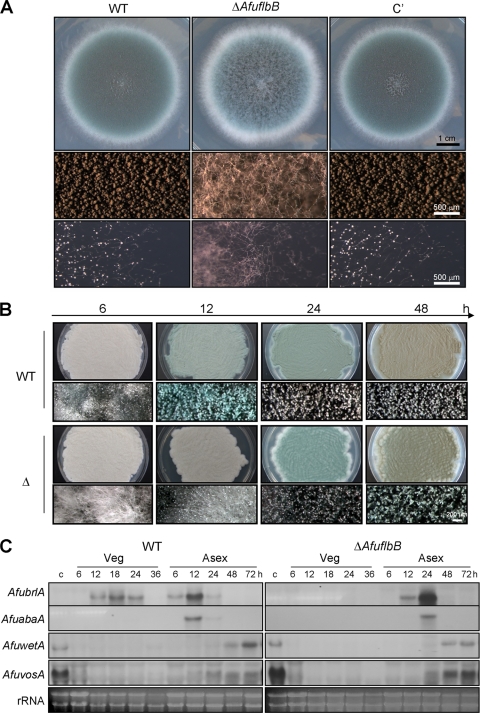

To understand the roles of AfuFlbB in growth and development in A. fumigatus, we first generated ΔAfuflbB strains by replacing the coding region of the AfuflbB genomic locus with the A. nidulans pyrG or argB marker. Complemented strains were subsequently generated by directly integrating the WT AfuflbB allele into the AfupyrG locus of the ΔAfuflbB mutant (TPX2.01). Several ΔAfuflbB strains displaying identical phenotypes were isolated and examined. When point inoculated on solid medium, the ΔAfuflbB mutant exhibited enhanced accumulation of undifferentiated hyphal mass with delayed/reduced conidiation (Fig. 2A; see also Fig. S1a in the supplemental material), whereas the WT and ΔAfuflbB AfuflbB+ complemented (hereinafter called C′) strains formed conidiophores abundantly. Moreover, the colony edge of WT and C′ strains showed the presence of abundant conidiophores, whereas the ΔAfuflbB mutant exhibited only extended hyphae (Fig. 2A, middle and bottom panels). Quantitative analyses of conidia per fungal colony grown on solid medium further demonstrated that the asexual spore production in the ΔAfuflbB mutant was dramatically decreased, approximately 50% to 70% of the levels of the WT and C′ strains (see Fig. S1a). These results suggest that AfuflbB is necessary for normal levels of conidiation on air-exposed solid culture.

Fig. 2.

Requirement of AfuflbB for proper asexual development. (A) Photographs of the colonies of WT (AF293), ΔAfuflbB (TKSS1.01), and complemented (C′; TPX5.10) strains grown on solid MMG with 0.5% YE at 37°C for 3 days (top panels) and the close-up views of the colonies (middle and bottom panels). (B) Progression of synchronized asexual development of the WT and ΔAfuflbB (Δ) strains on solid MMG with 0.1% YE. Numbers indicate the time (hours) postinduction. Note the color differences between the WT and ΔAfuflbB strains. (C) Northern blot analyses for levels of AfubrlA, AfuabaA, AfuwetA, and AfuvosA transcripts in the WT and ΔAfuflbB strains during the life cycle. Numbers indicate the time (hours) in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE (Veg) or of post-asexual developmental induction (Asex). Equal loading of total RNA was demonstrated by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA.

We further examined the effects of ΔAfuflbB during asexual developmental induction. As shown in Fig. 2B, upon induction, the ΔAfuflbB mutant exhibited enhanced proliferation of vegetative cells with delayed progression of conidiation. Moreover, whereas the WT strain began to show accumulation of AfubrlA mRNA at 6 h, with a peak at 12 h postinduction, the ΔAfuflbB mutant started to express AfubrlA at 12 h, with a peak at 24 h; i.e., there was about a 6- to 12-h delay in AfubrlA expression. Consequently, AfuabaA expression was delayed in the null mutant as well (Fig. 2C). However, expression patterns of AfuwetA and AfuvosA, which are mainly required for the late phase of conidiation, were not different between WT and the null mutant. These results indicate that AfuFlbB is necessary for proper expression of AfubrlA and AfuabaA during the initiation and progression of conidiation.

Effects of ΔAfuflbB in liquid submerged culture.

To further investigate the roles of AfuFlbB, the conidia of WT, ΔAfuflbB, and C′ (ΔAfuflbB AfuflbB+) strains were inoculated into liquid MMG with 0.1% YE, and morphologies and cell viabilities were examined. As shown in Fig. 3A, whereas WT and C′ strains started to produce simple conidiophores within 18 h, the ΔAfuflbB mutant failed to sporulate even after 96 h in submerged liquid culture (data not shown), indicating that AfuFlbB is required for development under these conditions. Furthermore, in accordance with these observations, the WT accumulated AfubrlA mRNA at 12 to 24 h of vegetative growth, whereas no AfubrlA expression was detected in the AfuflbB null mutant (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 3.

Effects of ΔAfuflbB in liquid submerged culture. (A) Photomicrographs of the mycelium of WT (AF293), ΔAfuflbB (Δ; TKSS1.01) and complemented (C′; TPX5.10) strains grown in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE for 18 h at 37°C and 250 rpm. The arrows indicate conidiophore structures. Note that WT and C′ strains started to produce vesicles at 18 h, whereas the ΔAfuflbB mutant fails to develop. (B) Viability of WT, ΔAfuflbB (Δ), and C′ strains grown in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE at 37°C and 250 rpm for the period of 5 days. Data represent the mean values (± standard deviations) of three independent experiments. Note that the ΔAfuflbB mutant exhibits accelerated cell death at days 4 and 5. (C) Apoptotic cell death levels of WT, ΔAfuflbB (Δ), and C′; strains grown in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE at 37°C for 4 days were examined by Evans blue staining. Note the clear differences in the levels of staining among the mycelia.

To examine whether the absence of AfuflbB influences cell viability, Alamar blue reduction assays were carried out (Fig. 3B). While all strains examined maintained equally high levels of cell viability until day 3, the ΔAfuflbB mutant exhibited drastically reduced cell viability at days 4 and 5. In particular, at day 4 the ΔAfuflbB mutant exhibited 52% of cell viability, whereas WT and C′ strains showed 94% and 92% of cell viability, respectively. All strains tested continued to lose cell viability up to day 6, when no differences in the viability were observable (data now shown). To further test whether the reduced cell viability was due to cell death, the hyphal cells of the WT, ΔAfuflbB, and C′ strains were stained with Evans blue and microscopically examined. As shown in Fig. 3C, compared to the WT and C′ strains, most of the ΔAfuflbB cells were intensely strained with the dye, indicating extensive cell death at day 4. However, when mycelial dry weights of these strains were measured, no obvious differences among WT, C′, and ΔAfuflbB strains were observable even at days 4 and 5 (data not shown). These results indicate that the absence of AfuflbB results in accelerated cell death but not autolysis in liquid submerged culture, and they support the idea that fungal autolysis and cell death are separate processes (27).

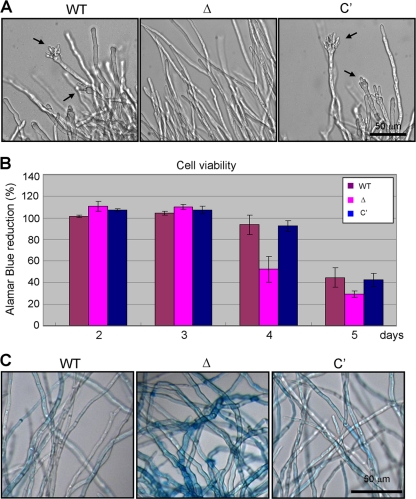

Both AfuFlbB polypeptides are required for proper asexual development.

The presence of two overlapping AfuflbB transcripts with distinct expression patterns led us to test whether both are required for proper development in A. fumigatus. This was accomplished by constructing two specific AfuflbB mutant alleles driven by the native AfuflbB promoter carrying a change from ATG (Met) to GCC (Ala) at each of the predicted start codons (Fig. 4A). Along with the WT allele, each mutant allele was integrated into the AfupyrG locus of the AfuflbB deletion mutant (TPX2.01), and the following three strains were generated (Fig. 4A): the ΔAfuflbB AfuflbB+ strain (C′; strain TPX6.01), the ΔAfuflbB AfuflbBα strain (hereinafter called α; TPX8.02), and the ΔAfuflbB AfuflbBβ strain (hereinafter called β; TPX7.06).

Fig. 4.

Both polypeptides are required for proper asexual development. (A) Schematics of the three AfuflbB alleles used for complementation. The predicted start codons (ATG) of the AfuflbB+ allele were replaced with GCC, leading to the AfuflbBα and AfuflbBβ alleles. (B) Photographs of the colonies of WT (AF293), ΔAfuflbB (Δ; TKSS1.01), C′ (TPX6.01; ΔAfuflbB AfuflbB+), α (TPX8.02; ΔAfuflbB AfuflbBα), and β (TPX7.06; ΔAfuflbB AfuflbBβ) strains grown on solid MMG with 0.1% YE for 3 days. (C) Progression of synchronized asexual development of the WT, ΔAfuflbB (Δ), C′, α, and β strains on solid MMG with 0.1% YE. Numbers indicate the time (hours) postinduction. The right panel shows the corresponding Northern blot of the samples taken from developmental induction. Equal loading of total RNA was demonstrated by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. (D) Photomicrographs of the mycelium of the WT, ΔAfuflbB (Δ), C′, α, and β strains grown in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE at 37°C and 250 rpm for 18 h. Note that the ΔAfuflbB, α, and β strains do not produce any conidiophore structures, whereas the WT and C′ strains start to form vesicles (marked by arrows) at 18 h.

To test the requirement for the two polypeptides, we first examined the ability of WT, ΔAfuflbB, C′, α, and β strains to produce conidia by point inoculation on solid medium. As shown in Fig. 4B, whereas the WT AfuflbB allele fully complemented the ΔAfuflbB strain, the AfuflbBα or AfuflbBβ allele restored conidiation to ∼80% of the levels of the WT and C′ strains (see Fig. S1b in the supplemental material), indicating that both polypeptides are required for normal conidiation. To further examine the requirement for two polypeptides, the mycelia of these strains were transferred onto solid medium, and progression of conidiation was examined (Fig. 4C). As shown, the WT and C′ strains started to produce conidiophores at 6 h, whereas the ΔAfuflbB mutant began to form conidiophores at 12 h postinduction. Similar to the ΔAfuflbB strain, the AfuFlbBα and AfuFlbBβ strains showed enhanced hyphal proliferation at 6 h and began to sporulate at 12 h postincubation. However, levels of AfubrlA mRNA in these strains were somewhat inconsistent with the delayed conidiation phenotype. As shown in Fig. 4C, it appears that the α strain started to express AfubrlA from 6 h, with a peak at 12 h, followed by a gradual decrease, whereas the β strain hardly expressed AfubrlA at 6 h, with a peak at 12 h, followed by a dramatic decrease. These results suggest that both polypeptides are necessary for proper asexual development in A. fumigatus and that expression of AfubrlA might be one of many required events for proper conidiation.

The above-mentioned strains were further examined in liquid submerged culture for asexual development. As shown in Fig. 4D, while the WT and C′ strains started to produce conidiophores within 18 h, the ΔAfuflbB mutant did not produce any developmental structures at this time and up to 96 h (data not shown). Interestingly, the α and β strains failed to produce any conidiophores until 48 h (data not shown), indicating that AfuFlbBα and AfuFlbBβ are individually required for proper development in liquid submerged culture.

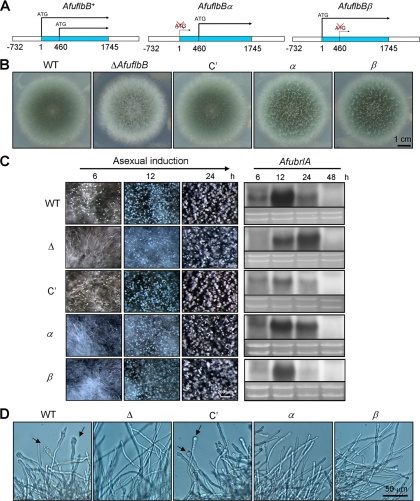

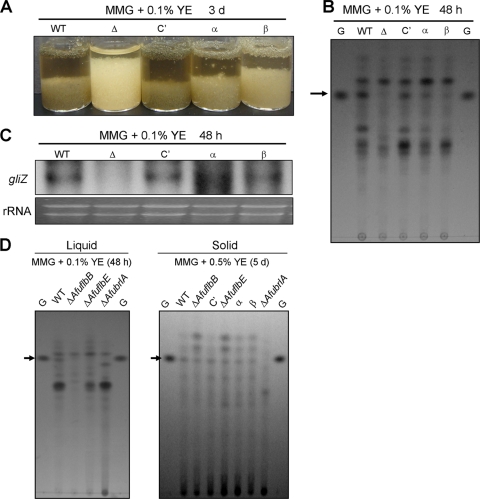

Differential requirement of developmental regulators for proper gliotoxin production.

During the cultivation of these strains in liquid submerged culture, we noticed the differences in pigmentation (Fig. 5A). We carried out TLC examination of the chloroform extracts of culture filtrates of various strains grown in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE at 37°C for 2 days. As shown in Fig. 5B, whereas gliotoxin was clearly detectable in the WT and C′ strains, it could not be detected in the chloroform extract of the ΔAfuflbB mutant. On the other hand, a small amount of gliotoxin was detectable in the chloroform extracts of the α and β strains. Northern blot analyses indicate that gliZ mRNA (3) is absent in the ΔAfuflbB mutant but present in the WT, C′, α, and β strains (Fig. 5C). We further examined the ΔAfuflbE and ΔAfubrlA mutants for the ability to produce gliotoxin. These mutants were defective in biosynthesis of gliotoxin in liquid submerged culture (Fig. 5D, left panel). However, under air-exposed solid culture conditions, the WT and mutant strains tested, except for the ΔAfubrlA mutant, produced similar amounts of gliotoxin (Fig. 5D, right panel). These results indicate that AfuflbB is (likely indirectly) associated with gliotoxin biosynthesis and that both polypeptides are required for proper production of gliotoxin in liquid submerged culture. Furthermore, the results suggest a potential key role of AfubrlA in gliotoxin biosynthesis (see Discussion).

Fig. 5.

Differential requirement of AfuflbB and other developmental regulators for gliotoxin production. (A) Photographs of relevant strains grown in liquid submerged culture for 3 days. Note the differences in pigmentation. (B) TLC of gliotoxin produced after 2 days of liquid submerged culture of the WT (AF293), ΔAfuflbB (Δ; TKSS1.01), C′ (TPX6.01), α (TPX8.02), and β (TPX7.06) strains. Toluene-acetate-formic acid (5:4:1) was used as developing solvent. (C) Effects of ΔAfuflbB on expression of gliZ. Northern blot of gliZ at 2 days is presented. Equal loading of total RNA was demonstrated by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. (D) TLC of the chloroform extracts of various strains including the ΔAfuflbE (TKSS6.07) and ΔAfubrlA (A1176) mutants grown in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE for 2 days or on solid MMG with 0.5% YE for 5 days. Note the lack of gliotoxin production by ΔAfubrlA. G, gliotoxin standard.

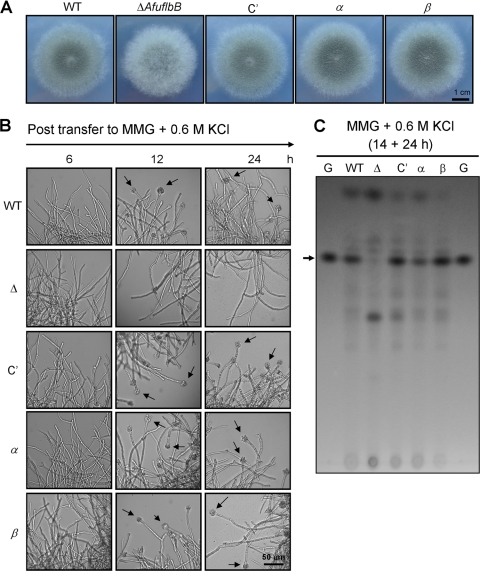

KCl can suppress the developmental defects caused by the lack of one, but not both, of the AfuFlbB polypeptides.

As previous studies demonstrated that unfavorable conditions including salt stress (11) can induce conidiation in A. nidulans, we investigated whether addition of KCl affects development of the above-mentioned strains. We first tested the effects by point inoculating the WT, ΔAfuflbB, C′, α, and β strains on solid MMG containing 0.6 M KCl and examining the morphologies and conidiation levels. We found that while the ΔAfuflbB mutant still exhibited delayed/reduced conidiation, the WT, C′, α, and β strains all formed a normal layer of conidiophores (Fig. 6A). Moreover, quantitative analyses of conidia produced by these strains indicate that while the ΔAfuflbB mutant produced only 70% conidia compared to WT and C′ strains, the α and β strains produced the same levels of conidia as the WT and C′ strains (data not shown), suggesting that 0.6 M KCl can suppress the developmental defects caused by the absence of one, but not both, of the AfuFlbB polypeptides.

Fig. 6.

Differential suppression of developmental defects by 0.6 M KCl. (A) Photographs of the colonies of WT (AF293), ΔAfuflbB (Δ; TKSS1.01), C′ (TPX6.01), α (TPX8.02), and β (TPX7.06) strains grown on MMG with 0.1% YE and 0.6 M KCl at 37°C for 3 days. (B) Photomicrographs of the mycelium of the WT, ΔAfuflbB (Δ), C′, α, and β strains cultured for 14 h in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE and then transferred into MMG supplemented with 0.6 M KCl. Numbers indicate incubation time posttransfer. Conidiophore structures are marked by arrows. Note that only the ΔAfuflbB mutant failed to develop. (C) TLC of gliotoxin in the presence of 0.6 M KCl in liquid submerged culture. After growth in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE for 14 h, the mycelia of relevant strains were transferred into MMG supplemented with 0.6 M KCl and further cultured at 37°C for 24 h. G, gliotoxin standard.

We further examined the suppressive effect of high KCl concentrations in liquid submerged culture. These strains were first cultured in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE for 14 h, and the mycelium was then collected and transferred into liquid MMG-0.6 M KCl and further examined for phenotypic changes. As shown in Fig. 6B, the WT and C′ strains began to form conidiophores at 12 h posttransfer, whereas the ΔAfuflbB mutant failed to produce any conidiophore-like structures up to 48 h. As observed in solid culture, the α and β strains produced conidiophores abundantly, just like the WT and C′ strains, further suggesting that KCl can replace one, but not both, of the two AfuFlbB polypeptides for asexual development.

We further investigated whether KCl can suppress the defective gliotoxin production caused by mutations in AfuflbB. TLC analyses of the chloroform extracts of the WT, C′, α, and β strain cultures at 24 h after transfer to KCl-supplemented medium (Fig. 6C) showed equal levels of gliotoxin, whereas the ΔAfuflbB mutant appeared to be still impaired in gliotoxin production. These results further suggest that KCl can suppress the gliotoxin defect caused by the absence of one, but not both, of the polypeptides and that asexual development and gliotoxin production in A. fumigatus might be closely associated potentially through AfuBrlA (see Discussion).

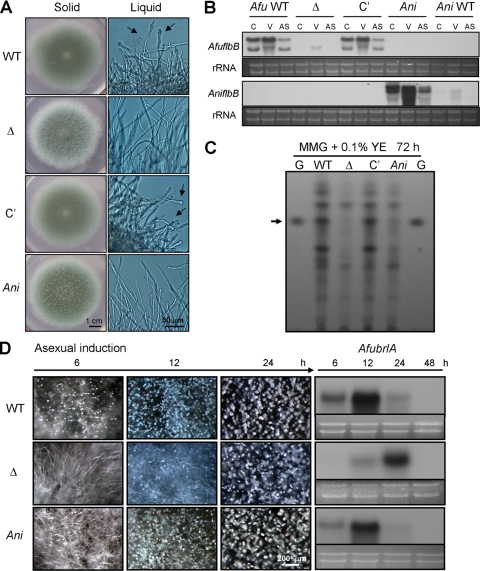

AniFlbB partially complements ΔAfuflbB.

As A. nidulans flbB is predicted to encode only one polypeptide similar to AfuFlbBβ, we hypothesized that AniflbB cannot fully complement the ΔAfuflbB strain. This was tested by introducing AniflbB+ to the AfupyrG locus of the ΔAfuflbB mutant and examining its conidiation potential. As shown in Fig. 7A, when grown on solid medium, the ΔAfuflbB AniflbB+ (hereinafter called Ani) strain partially restored asexual sporulation to the α and β strains (compare strains in Fig. 4B). Northern blot analysis confirmed that the introduced AniflbB gene is highly expressed (Fig. 7B). Quantitative analyses of sporulation indicate that the Ani strain produced conidia to a level similar to the levels of the α and β strains (see Fig. S1b in the supplemental material). Moreover, similar to the α and β strains in liquid submerged culture, the Ani strain failed to develop up to 48 h (data not shown). In addition, during developmental induction, the Ani strain exhibited delayed conidiation, despite recovery of nearly WT levels of AfubrlA expression, as observed in the α and β strains (Fig. 7D). Finally, gliotoxin production was only partially restored by AniFlbB (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these results further corroborate that both AfuFlbB polypeptides are essential for proper asexual development and gliotoxin production and suggest that A. fumigatus has evolved uniquely with two transcription units of AfuflbB.

Fig. 7.

Partial complementation of ΔAfuflbB by AniflbB. (A) Phenotypic analyses of the WT (AF293), ΔAfuflbB (Δ; TKSS1.01), complemented (C′; ΔAfuflbB AfuflbB+; TPX5.10) and cross-complemented (Ani; ΔAfuflbB AniflbB+; TPX9.03) strains grown on solid MMG with 0.1% YE at 37°C for 3 days or in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE at 37°C and 250 rpm, for 18 h. (B) Northern blot showing mRNA levels of AfuflbB and AniflbB in A. fumigatus WT, ΔAfuflbB, C′, Ani, and A. nidulans WT (FGSC4) strains. C, conidia; V, 12-h vegetative; AS, 12-h asexual induction. Note that AniflbB is highly expressed under the ΔAfuflbB background. (C) TLC for gliotoxin production in liquid submerged culture of relevant strains for 3 days. G, gliotoxin standard. (D) Progression of synchronized asexual development in WT (AF293), ΔAfuflbB (Δ), C′, and Ani strains on solid MMG with 0.1% YE. Numbers indicate the time (hours) postinduction. Right panel shows the corresponding Northern blot for AfubrlA in the samples taken from asexual induction. Equal loading of total RNA was demonstrated by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA.

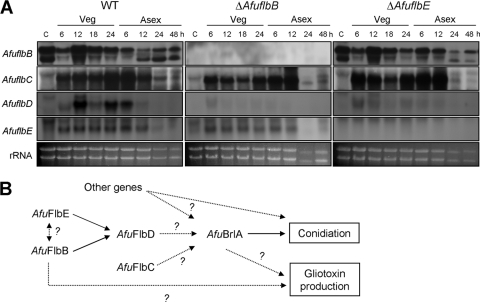

Genetic interactions between upstream developmental regulators in A. fumigatus.

To dissect genetic interactions between key developmental regulators, a series of Northern blot analyses was carried out to test the need for AfuFlbB and AfuFlbE for proper expression of AfuflbB-AfuflbE. As shown in Fig. 8A, the absence of AfuflbB or AfuflbE abolished accumulation of AfuflbD mRNA throughout the life cycle, indicating that both AfuFlbB and AfuFlbE are required for expression of AfuflbD. However, expression of AfuflbB and AfuflbE was not affected by the absence AfuflbE and AfuflbB, respectively. Moreover, expression of AfuflbC was independent of either AfuflbB or AfuflbE. These results suggest that the proposed model for genetic interactions among upstream developmental regulators in A. nidulans (16, 17) is partially applicable for A. fumigatus (Fig. 8B; see also Discussion).

Fig. 8.

Genetic interactions between upstream developmental regulators in A. fumigatus. (A) Levels of AfuflbB, AfuflbC, AfuflbD, and AfuflbE transcripts in WT (AF293), ΔAfuflbB (TKSS1.01), and ΔAfuflbE (TKSS6.07) strains throughout the life cycle. Numbers indicate the time (hours) in liquid MMG with 0.1% YE (Veg) or of post-asexual developmental induction (Asex). A band shown between the two AfuflbB transcripts is due to nonspecific binding of the probe to rRNA. (B) A genetic model for upstream regulation of asexual development in A. fumigatus (see Discussion).

DISCUSSION

A. fumigatus is an important opportunistic human pathogenic fungus that causes a severe and usually life-threatening systemic mycosis termed invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised individuals (8). In addition to a massive number of small hydrophobic asexual spores, A. fumigatus produces the toxic secondary metabolite gliotoxin, a key virulence determinant contributing to its pathogenesis (18).

Based on the studies of growth and development in the distantly related A. nidulans, we have been dissecting the roles of genes associated with development in A. fumigatus (17, 20, 40; also Tao and Yu, unpublished). Our previous studies demonstrated that functions of the central regulators BrlA, AbaA, and WetA in conidiogenesis are conserved in A. nidulans and A. fumigatus (20; also Tao and Yu, unpublished). On the other hand, while the upstream developmental regulator AfuFlbE plays a crucial role in proper development of A. fumigatus (17), AfuFluG is not essential for conidiation (20). In the present study, we further expanded our understanding of upstream regulation in A. fumigatus development by characterizing AfuflbB. The deletion of AfuflbB resulted in a phenotype similar to that caused by the A. nidulans flbB null mutation but differing in its severity. In contrast to the ΔAniflbB strain with a proliferation of undifferentiated aerial hyphae and the nearly absent conidiophore formation (11), the AfuflbB null mutant exhibited a certain level of asexual development under air-exposed culture conditions although the process was delayed and the conidiation level was reduced. Conversely, AfuflbB deletion strains did not develop in liquid submerged culture, whereas A. fumigatus WT and C′ strains elaborated conidiophores abundantly within 24 h. We further asked whether the conidiation defects caused by ΔAfuflbB were associated with altered expression of AfubrlA and other conidiation-specific genes. Consistent with a delay in asexual development in the ΔAfuflbB mutant under synchronized developmental induction conditions (Fig. 2B), expression of AfubrlA was delayed for 6 to 12 h (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, expression of AfuabaA, another key regulator directly activated by AfuBrlA (Tao and Yu, unpublished), was delayed about 12 h. However, AfuwetA and AfuvosA, whose transcripts mainly accumulate at the late phases of asexual development (24; also Tao and Yu, unpublished), were not affected. We speculate two possible explanations for this: AfuWetA and AfuVosA function in the process of conidium maturation (wall formation and trehalose biogenesis) and confer spore viability, which is a separate phase from the initiation of conidiophore formation activated by AfuBrlA and AfuAbaA (23), and/or additional components are associated with activation of AfuwetA and AfuvosA (Tao and Yu, unpublished).

Probably the most important finding of the present study is that two overlapping mRNAs and polypeptides are encoded by the AfuflbB gene and that both are necessary for proper morphological development and gliotoxin biogenesis in A. fumigatus. The longer transcript AfuflbBβ is present at a relatively constant level throughout the life cycle, whereas the shorter transcript AfuflbBα specifically accumulates during the progression of conidiation. In A. nidulans, only one transcript is encoded by AniflbB, which primarily accumulates during asexual development (11). AniFlbB (426 aa) shares a high similarity with AfuFlbBβ (420 aa). Examination of the mutants that produce only one of the two predicted polypeptides reveals that both AfuFlbBα and AfuFlbBβ are required for proper asexual development (Fig. 4B; see also Fig. S1b in the supplemental material), indicating that the two proteins likely play an additive and/or complementary role. This is supported by the fact that 0.6 M KCl can suppress the developmental defects caused by the absence of one, but not both, of the polypeptides and that cross-species complementation of ΔAfuflbB with AniflbB resulted in a partial restoration of asexual development and gliotoxin production, as observed in AfuflbBα and AfuflbBβ strains. Our preliminary data indicate that both AfuFlbBβ and AfuFlbBα show trans-activation ability in yeast (N. J. Kwon and J.-H. Yu, unpublished data), suggesting that both can act as putative bZIP transcription factors. Our Northern blot analyses of the α and β mutants reveal that only the AfuflbBβ mRNA is produced in both the AfuflbBα and AfuflbBβ strains, indicating that both AfuFlbBβ and AfuFlbBα are necessary for expression of AfuflbBα, which specifically accumulates during conidiogenesis (data not shown). Additional molecular studies dissecting the complex regulation of AfuflbB gene expression need to be carried out.

Aspergillus secondary metabolite production is a complex process, yielding various compounds including carcinogenic mycotoxins, such as aflatoxins (AFs) and sterigmatocystin (ST), and is closely associated with morphological development (6, 15, 38). Our present studies suggest that gliotoxin production and asexual development might be interconnected through the activities of the key developmental regulator BrlA in A. fumigatus. Whereas the deletion of AfuflbB totally abolished gliotoxin production (Fig. 5B) under liquid submerged culture conditions, strains carrying either AfuFlbBβ or AfuFlbBα or both produce gliotoxin, although the amount was reduced compared to levels of the WT and C′ strains. Indeed, gliotoxin production patterns (Fig. 5B and D) are somewhat consistent with the levels of asexual development (Fig. 4B and D and 5A). This idea was further supported by the fact that under salt stress conditions, where all strains tested except the ΔAfuflbB mutant formed developmental structures (Fig. 6B), the α and β strains restored gliotoxin production and conidiation to the WT levels (Fig. 6C). Importantly, similar to ΔAfuflbB, the absence of AfuflbE abolishes gliotoxin production in liquid submerged culture (Fig. 5D) where the ΔAfuflbE mutant does not develop (see reference 17), and ΔAfubrlA eliminates gliotoxin production under liquid and/or solid culture conditions (Fig. 5D). These observations suggest that AfuBrlA might play a central role in the cooperative regulation of gliotoxin production and asexual development. Interestingly, multiple BrlA binding sites [BrlA response elements (BREs); 5′-(C/A)(G/A)AGGG(G/A)-3′] (7) are present in the promoter regions of 10 out of the 12 gliotoxin biosynthetic clustered genes (12, 18; data not shown). It would be of great interest to check whether AfuBrlA indeed binds to these regions and exerts direct regulation (activation) on many of the gliotoxin biosynthetic genes.

Recent studies in A. nidulans demonstrated that FlbB is necessary for expression of flbD encoding a c-Myb protein and that FlbB and FlbD activate brlA in a cooperative manner (14). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that FlbE and FlbB are functionally interdependent, physically interact in vivo, and are colocalized at the hyphal tip in an actin cytoskeleton-dependent manner in A. nidulans, and expression of these two genes is interdependent (13, 14). The A. fumigatus flbE gene is predicted to encode a 222-aa-length polypeptide and is required for normal conidiation (17) and gliotoxin production (Fig. 5D). Our preliminary study further suggests that AfuFlbD is essential for proper development in A. fumigatus (P. Xiao and J.-H. Yu, unpublished data). To examine potential genetic interactions among upstream developmental regulators in A. fumigatus, a series of expression studies was carried out, and the results suggest that A. fumigatus possesses an upstream regulatory cascade slightly different from the one proposed for A. nidulans (Fig. 8A and B). The observations that AfuflbB and AfuflbE are each expressed independently of each other and that both are required for proper expression of AfuflbD led to a model that AfuFlbB and AfuFlbE function upstream of AfuFlbD and cooperatively activate the expression of AfuflbD, which in turn results in activation of AfubrlA (Fig. 8B). Although at the transcriptional level AfuflbB and AfuflbE are independent of each other (Fig. 8A), we cannot exclude the possibility that the AfuFlbB and AfuFlbE proteins interact and form a functional complex, as found in A. nidulans (13). In addition, expression of AfuflbC is independent of AfuFlbB and AfuFlbE, indicating that AfuFlbC functions in a separate pathway, as found in A. nidulans; characterization of AfuflbC and additional developmental controllers is in progress.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ellin Doyle for reviewing the manuscript.

P.X. was supported by a Graduate Scholarship Program sponsored by the China Scholarship Council and the Ministry of Education of China. The work carried out at Daejon University was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2010-0007836) to K.-S.S. This work was primarily supported by National Science Foundation (IOS-0640067 and IOS-0950850) and Food Research Institute grants to J.-H.Y.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 17 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams T. H., Boylan M. T., Timberlake W. E. 1988. brlA is necessary and sufficient to direct conidiophore development in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell 54:353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams T. H., Wieser J. K., Yu J. H. 1998. Asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:35–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bok J. W., Chung D., Balajee S. A., Marr K. A., Andes D., Nielsen K. F., Frisvad J. C., Kirby K. A., Keller N. P. 2006. GliZ, a transcriptional regulator of gliotoxin biosynthesis, contributes to Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Infect. Immun. 74:6761–6768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boylan M. T., Mirabito P. M., Willett C. E., Zimmerman C. R., Timberlake W. E. 1987. Isolation and physical characterization of three essential conidiation genes from Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:3113–3118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brookman J. L., Denning D. W. 2000. Molecular genetics in Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvo A. M., Wilson R. A., Bok J. W., Keller N. P. 2002. Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:447–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Y. C., Timberlake W. E. 1993. Identification of Aspergillus brlA response elements (BREs) by genetic selection in yeast. Genetics 133:29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagenais T. R., Keller N. P. 2009. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22:447–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denning D. W. 1998. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:781–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etxebeste O., Herrero-García E., Araújo-Bazán L., Rodríguez-Urra A. B., Garzia A., Ugalde U., Espeso E. A. 2009. The bZIP-type transcription factor FlbB regulates distinct morphogenetic stages of colony formation in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 73:775–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etxebeste O., Ni M., Garzia A., Kwon N. J., Fischer R., Yu J. H., Espeso E. A., Ugalde U. 2008. Basic-zipper-type transcription factor FlbB controls asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 7:38–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardiner D. M., Howlett B. J. 2005. Bioinformatic and expression analysis of the putative gliotoxin biosynthetic gene cluster of Aspergillus fumigatus. FEMS. Microbiol. Lett. 248:241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garzia A., Etxebeste O., Herrero-García E., Fischer R., Espeso E. A., Ugalde U. 2009. Aspergillus nidulans FlbE is an upstream developmental activator of conidiation functionally associated with the putative transcription factor FlbB. Mol. Microbiol. 71:172–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garzia A., Etxebeste O., Herrero-García E., Ugalde U., Espeso E. A. 2010. The concerted action of bZip and cMyb transcription factors FlbB and FlbD induces brlA expression and asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 75:1314–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicks J. K., Yu J. H., Keller N. P., Adams T. H. 1997. Aspergillus sporulation and mycotoxin production both require inactivation of the FadA Gα protein-dependent signaling pathway. EMBO J. 16:4916–4923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon N. J., Garzia A., Espeso E. A., Ugalde U., Yu J. H. 2010. FlbC is a putative nuclear C2H2 transcription factor regulating development in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 77:1203–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon N. J., Shin K. S., Yu J. H. 2010. Characterization of the developmental regulator FlbE in Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2010.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon-Chung K. J., Sugui J. A. 2009. What do we know about the role of gliotoxin in the pathobiology of Aspergillus fumigatus? Med. Mycol. 47(Suppl. 1):S97–S103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackenzie D. W. R. 1988. Aspergillus in man, p. 1–8InVandenBossche H., Mackenzie D. W. R., Cauwenbergh G.(ed.), Aspergillus and aspergillosis. Plenum Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mah J. H., Yu J. H. 2006. Upstream and downstream regulation of asexual development in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1585–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinelli S. D., Clutterbuck A. J. 1971. A quantitative survey of conidiation mutants in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 69:261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirabito P. M., Adams T. H., Timberlake W. E. 1989. Interactions of three sequentially expressed genes control temporal and spatial specificity in Aspergillus development. Cell 57:859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ni M., Gao N., Kwon N. J., Shin K. S., Yu J. H. 2010. Regulation of Aspergillus conidiation, p. 559–576InBorkovich K. A., Ebbole D. J. (ed.), Cellular and molecular biology of filamentous fungi. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni M., Yu J. H. 2007. A novel regulator couples sporogenesis and trehalose biogenesis in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One 2:e970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reyes G., Romans A., Nguyen C. K., May G. S. 2006. Novel mitogen-activated protein kinase MpkC of Aspergillus fumigatus is required for utilization of polyalcohol sugars. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1934–1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhodes J. C., Askew D. S. 2010. Aspergillus fumigatus, p. 697–716InBorkovich K. A., Ebbole D. J. (ed.), Cellular and molecular biology of filamentous fungi. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin K. S., Kwon N. J., Kim Y. H., Park H. S., Kwon G. S., Yu J. H. 2009. Differential roles of the ChiB chitinase in autolysis and cell death of Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 8:738–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin K. S., Kwon N. J., Yu J. H. 2009. Gβγ-mediated growth and developmental control in Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr. Genet. 55:631–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao L., Gao N., Chen S., Yu J. H. 2010. The choC gene encoding a putative phospholipid methyltransferase is essential for growth and development in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Genet. 56:283–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Timberlake W. E. 1980. Developmental gene regulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Dev. Biol. 78:497–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasylnka J. A., Moore M. M. 2003. Aspergillus fumigatus conidia survive and germinate in acidic organelles of A549 epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 116:1579–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wieser J., Adams T. H. 1995. flbD encodes a Myb-like DNA binding protein that controls initiation of Aspergillus nidulans conidiophore development. Genes Dev. 9:491–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wieser J., Lee B. N., Fondon J. W., Adams T. H. 1994. Genetic requirements for initiating asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Genet. 27:62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xue T., Nguyen C. K., Romans A., Kontoyiannis D. P., May G. S. 2004. Isogenic auxotrophic mutant strains in the Aspergillus fumigatus genome reference strain AF293. Arch. Microbiol. 182:346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yelton M. M., Hamer J. E., de Souza E. R., Mullaney E. J., Timberlake W. E. 1983. Developmental regulation of the Aspergillus nidulans trpC gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80:7576–7580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yelton M. M., Hamer J. E., Timberlake W. E. 1984. Transformation of Aspergillus nidulans by using a trpC plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81:1470–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J. H., Hamari Z., Han K. H., Seo J. A., Reyes-Domínguez Y., Scazzocchio C. 2004. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulation in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:973–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu J. H., Keller N. P. 2005. Regulation of secondary metabolism in filamentous fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43:437–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J. H., Leonard T. J. 1995. Sterigmatocystin biosynthesis in Aspergillus nidulans requires a novel type I polyketide synthase. J. Bacteriol. 177:4792–4800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu J. H., Mah J. H., Seo J. A. 2006. Growth and developmental control in the model and pathogenic aspergilli. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1577–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.