Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine the relation of menstrual attitudes to menopausal attitudes and the demographic and health characteristics associated with each. This cross-sectional study consisted of a randomly selected sample of 1824 respondents aged 16 to 100 years in multi-ethnic Hilo, Hawai`i. Women completed questionnaires for demographic and health information, such as age, ethnicity, education, residency in Hawai`i, menopausal status, exercise, and attitudes toward menstruation and menopause. Women more often chose positive terms, such as “natural,” to describe menstruation (60.8%) and menopause (59.4%). In bivariate analyses, post-menopausal women were significantly more likely to have positive menstrual and menopausal attitudes than pre-menopausal women. Factor analyses were used to cluster attitudes followed by linear regression to identify demographic characteristics associated with factor scores. Asian-American ethnicity, higher education, reporting more exercise, and growing up outside of Hawai`i were associated with positive menstrual attitudes. Higher education, older age, post-menopausal status, growing up outside of Hawai`i and having hot flashes were associated with positive menopausal attitudes. Bivariate correlation analyses suggested significant associations between factor scores for menstrual and menopausal attitudes. Both negative and positive menstrual attitudes were positively correlated with the anticipation of menopause, although negative attitudes toward menstruation were negatively correlated with menopause as a positive, natural life event. Demographic variables, specifically education and where one grows up, influenced women’s attitudes toward menstruation and menopause and should be considered for inclusion in subsequent multi-ethnic studies. Further research is also warranted in assessing the relationship between menstrual and menopausal attitudes.

Keywords: Attitudes, menstruation, menopause, ethnicity, exercise, hotflashes, menstrual cramps

INTRODUCTION

Attitudes toward menstruation and menopause are shaped by both cultural and individual characteristics. Menstruation and menopause are not celebrated in western cultures, where they are depicted by the mass media and the health-care profession as something to be managed or remedied, and as something less than feminine (Del Saz-Rubio and Pennock-Speck 2009; Hutson et al. 2009; Johnston-Robledo 2006; Linton 2007; Luke 1997; Nelson and Signorielli 2007; Raftos et al. 1998; Rose et al. 2008).Conversely, menstruation has been viewed historically and cross-culturally as a natural phenomenon (Roberts 2004). In fact, a recent study found that the majority of women regarded menstruation as natural; only a small minority thought of it as a nuisance or a curse (Morrison et al. 2010). Prompting much of the current research about women’s attitudes toward cyclical bleeding is the recent introduction of birth control that suppresses menstruation (Edelman et al. 2007, Fruzzetti et al. 2008, Glasier et al. 2003, Rose et al. 2008; Sánchez-Borrego and García-Calvo 2008).

Menopause has also been medicalized, recently gaining media attention highlighting the findings of risks associated with hormone therapy and women’s and health-care practitioners’ responses (MacLennan et al. 2009; Rossouw et al. 2002; Sievert et al. 2008; Worcester 2004). Because most research on menopause has focused on the undesirable aspects, such as hot flashes and night sweats, this has inadvertently contributed to the negative social construction of menopause. Undoubtedly, in some cases, menopausal symptoms can be problematic and affect women’s quality of life but perceptions and attitudes toward menopause are also influenced by culture, education, and geography (Donati et al. 2009; Gannon and Ekstrom 1993; Hvas 2001; Leon et al. 2007). In fact, the last decade has seen an abundance of research on menopausal attitudes nationally and internationally, many of which highlight positive outcomes (Lindh-Åstrand et al. 2007; Utian and Boggs 1999).

Numerous researchers have examined attitudes toward menstruation (Sanchez-Borrego and García-Calvo 2008) and menopause (Kowalcek et al. 2005; Sommer et al. 1999), but noticeably absent is research on the interaction between the two and their associated demographic and health characteristics. McPherson and Korfine’s (2004) work, which indicated that women who had positive menarcheal experiences tended to have positive attitudes toward menstruation, prompted us to examine the relationship between menstrual and menopausal attitudes. The purpose of this study was to identify factors associated with attitudes toward menstruation and menopause in a randomly selected sample of 1824 women aged 16 to 100 years, drawn from the multi-ethnic population in Hilo, Hawai`i. Our first hypothesis was that women with a positive attitude toward menstruation would have a positive attitude toward menopause because of a positive inclination toward natural processes. Alternatively, we hypothesized that those with a negative attitude toward menstruation would have a negative attitude toward menopause because of undesireable experiences (e.g. menstrual cramps or hot flashes). Additionally, we hypothesized that women with a negative attitude toward menstruation would have a positive attitude toward menopause, as they anticipated the end of the monthly bleeding. Additional variables investigated were those previously found to affect attitudes toward menstruation and menopause in other studies, such as age, menopausal status (Hvas 2001), history of hysterectomy (Bowles 1986; Gannon and Ekstrom 1993; Neugarten et al. 1963; Sievert and Espinosa-Hernandez 2003; Sommer et al. 1999; Wagner et al. 1995), education (Lee 2002), ethnicity and where a woman spent the formative years of her life (Avis et al. 2001; Edelman et al. 2007; Sommer 1999), and health-related behaviors such as exercise (Daley et al. 2009; Gallicchio et al. 2009; Jahromi et al. 2008; Sommer 1999).

METHODS

Study population

The Hilo Women’s Health Survey was conducted in Hilo, Hawai`i to assess women’s overall health. From the summer of 2004 to the summer of 2005, 6,401 survey packets were sent to a randomly selected sample of households using the County of Hawai`i tax map key (see Sievert et al. 2007 for more details). The information packet gave an overview of the study, its purpose, assurance of confidentiality, subsequent stages of the study, and invited any women of the household over 19 years of age to complete and return the survey in the enclosed, self-addressed envelope. One reminder notice was mailed to encourage the return of the survey. Of the 1824 (28.5%) surveys returned, nine were from women less than 19 years old. Their responses were included in the analyses. Although the questionnaire was anonymous and because surveys were sent to addresses, not individuals, women had the option of giving us their names and contact information to receive a $20 stipend. If women sent us their names, the data were de-identified immediately. The study was approved by the University of Hawai`i Committee on Human Studies.

Measurements

The questionnaire included demographic questions developed specifically for the Hilo research site (Brown et al. 1998, 2001), frequently used symptom lists for symptoms associated with menopause (Avis et al. 1993; Kronenberg 1990), attitude lists developed from open-ended interviews prior to studies carried out in New York and Massachusetts (Leidy et al. 2000; Sievert et al. 2001), and measures of menopausal status that followed the convention of the WHO (1981; 1996). The questionnaires were pilot-tested with women aged 40–60 years, (n=8, including 2 Japanese, 1 Chinese, and 1 woman with mixed Hawaiian/Japanese ancestry), then revised and piloted again (n=11, including 1 Japanese, 1 Chinese, and 4 women of mixed ancestry.) Respondents were asked for their age, education, ethnicity (but not race)i, whether they were born in Hawai`i, on the US mainland, or outside of the US. Women were asked general health-related questions, such as whether they exercised, had experienced menstrual cramps, or underwent a hysterectomy. Pre-menopausal women had regular cycles; peri-menopausal women had cycles that had changed in length by 7 days or missed more than 1 cycle in the last 12 months, and post-menopausal women had ceased menstruating for at least 12 months. Women on cycle-suppressing contraceptives were treated as pre-menopausal. Women who had undergone hysterectomies were treated as post-menopausal.

To measure attitudes toward menstruation, women were asked to check seven possible characteristics – a curse, a sign of fertility, no problem, a relief from premenstrual symptoms (PMSx)ii, a nuisance, natural, and/or a sign of femininity – when asked “What words would you use to describe menstruation?” Correspondingly, they were given eight possible characteristics for menopause – freedom, natural, loss of fertility, eagerly awaited, onset of old age, loss of femininity, a nuisance, and/or no problem – when asked “How would you describe menopause?” For both questions, they could choose more than one characteristic.

Statistical Analyses

Frequencies for attitudes toward menstruation and menopause were assessed by Chi-square analyses across menopausal status categories (pre-, peri, post) and for the total sample. Separate factor analyses were conducted to examine which menstrual and menopausal attitudes clustered together. Principal component analyses were used to extract two factors for menstrual attitudes and three factors for menopausal attitudes (based on the criteria of eigen values greater than 1.00) using a varimax rotation. Factor scores of > + .400 and < −.400 were used to identify the attitudes associated with each cluster.

The factor scores were used as dependent variables in a backward stepwise linear regression to examine demographic, health, and lifestyle characteristics associated with menstrual and menopausal attitudes. Criteria used for backward selection were F ≤ 0.05 for entry, and F ≥ 0.10 for removal and P < 0.05. Variables entered into the linear regression analyses were age at the time of survey, menopausal status (pre-, peri-, post), ethnicity (European-American, Japanese-American, Chinese, Filipino, Other/Mixed), level of education (high school or less, some college or college graduate, some graduate school or higher degree), where the participant grew up (HI, US mainland, outside of the US), exercise or sports participation (no, yes), having had a hysterectomy (no, yes), having ever had menstrual cramps (no, yes), and having ever had hot flashes. Factor scores were used to examine the correlation between menstrual and menopausal attitudes. R2 was used to assess the fit of the linear regression models. Interactions among variables were not examined.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The average age of women in our sample was 47.2 (s.d. 16.4) years, and an almost equal proportion of European-American (22.4) and Japanese-American (25.9) women participated (Table 1). The ethnic proportions of the participants were similar to those reported in the 2000 Census figures for Hilo (Population 40,759; 17.1% white, 26.7% Japanese, 1.6% Chinese, 5.8% Filipino, and 44.4% Other/Mixed). Approximately half of the women were pre-menopausal with the other half predominantly post-menopausal. Almost 80% of our sample had some college education or more. Most women grew up in Hawai`i. Almost one-fifth of our sample underwent a hysterectomy. Over half played sports or exercised regularly. The majority of respondents said they had experienced menstrual cramps and almost half had experienced a hot flash.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (Percentages, except for age)

| N | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1797 | Mean 47, s.d. 16.4 Range 16–100 | |

| Menopausal Status | 1786 | Percent | |

| Pre | 51.7 | ||

| Peri | 5.5 | ||

| Post | 42.8 | ||

| Ethnicity | 1802 | ||

| European-American | 22.4 | ||

| Japanese-American | 25.9 | ||

| Chinese | 1.3 | ||

| Filipino | 2.9 | ||

| Other/Mixed | 47.5 | ||

| Education | 1824 | ||

| High school or less | 21.8 | ||

| Some college or degree | 57.2 | ||

| Grad school or more | 20.9 | ||

| Grew Up | 1812 | ||

| In Hawaii | 74 | ||

| On the US mainland | 20.5 | ||

| Outside US | 5.5 | ||

| Hysterectomy | 1720 | 18.6 | |

| Menstrual Cramps* | 1701 | 84.1 | |

| Hot Flashes* | 1697 | 46.7 | |

| Exercise/ Play sports | 1796 | 55.6 | |

ever experienced

Frequencies

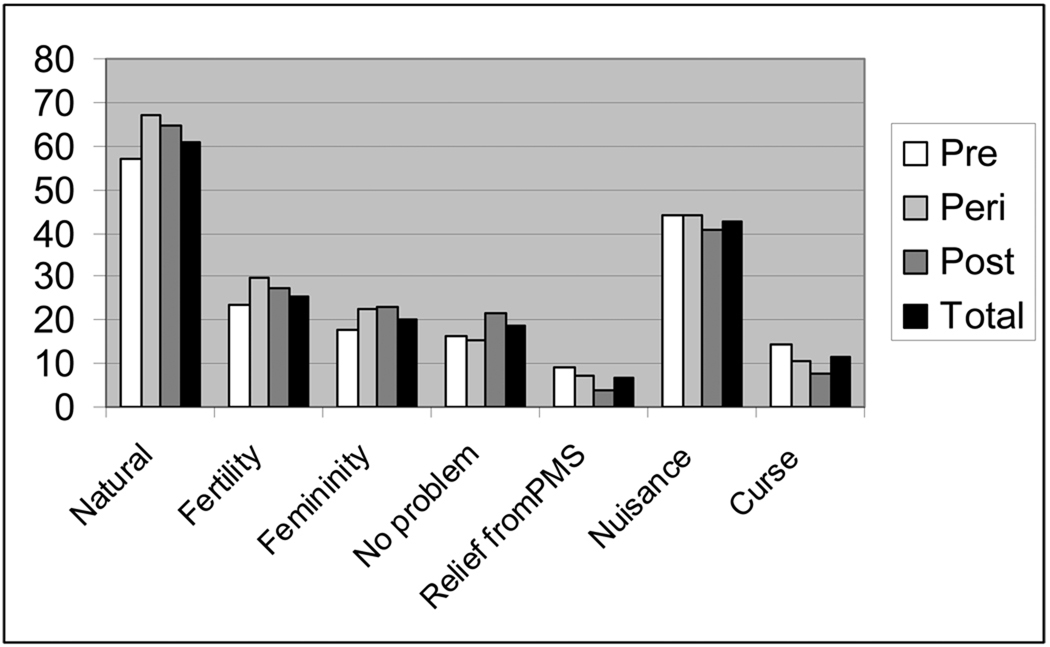

More than 60% of the respondents regarded menstruation as natural (Figure 1) with significantly more post-menopausal than pre-menopausal women reporting this (p<0.01; Table 2). Of the total, 20.2% associated menstruation with femininity but significantly more post-menopausal than pre-menopausal women did so. Significantly more post-menopausal than pre-menopausal women viewed menstruation as no problem. Almost 7% of women regarded menstruation as a relief from PMSx; pre-menopausal women were more likely to report this than post-menopausal women. Less than half of all participants thought menstruation was a nuisance with no significant differences across the menopausal status groups. Less than 12% of the sample regarded menstruation as a curse, with significantly more pre-menopausal than post-menopausal women making that association (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Menstrual attitudes by menopausal status (Percentages)

Table 2.

Attitudes toward menstruation by menopausal status, n=1760 (Percentages)

| Percent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “What words would you use to describe menstruation?” | Pre-menopausal | Peri-menopausal | Post-menopausal | P-values |

| Natural | 57 | 67 | 65 | .002 |

| Fertility | 23 | 30 | 27 | .098 |

| Femininity | 18 | 23 | 23 | .021 |

| No problem | 16 | 15 | 22 | .019 |

| Relief from PMSx | 9 | 7 | 4 | .000 |

| Nuisance | 44 | 44 | 41 | .305 |

| Curse | 15 | 10 | 8 | .000 |

PMSx = premenstrual symptoms

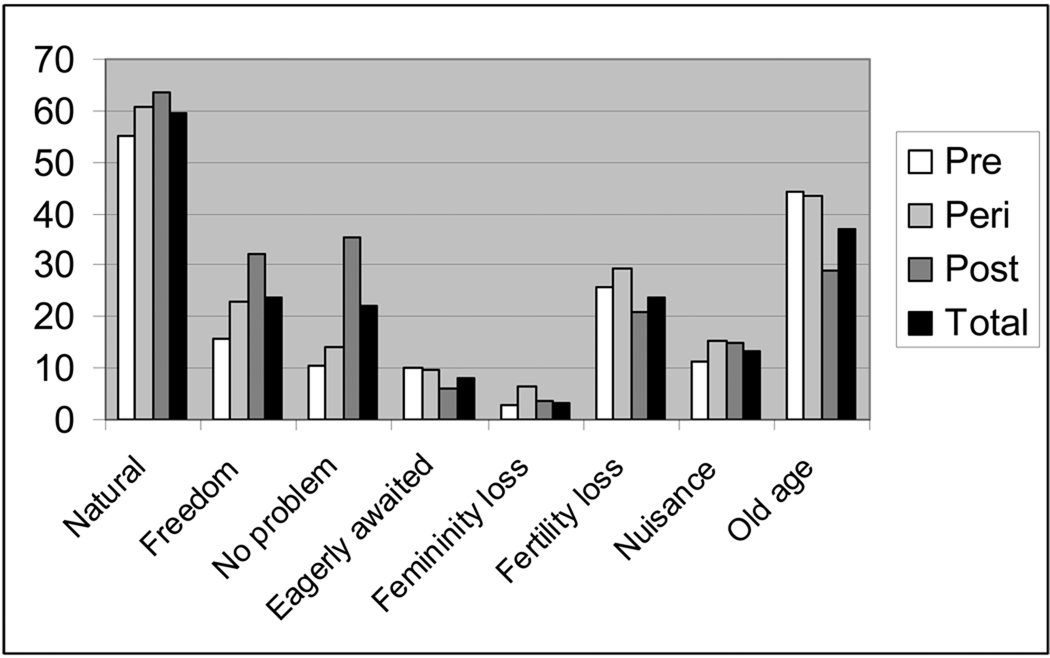

Almost 60% (59.4%) of all women regarded menopause as natural (Figure 2) with significantly more post-menopausal women reporting this (Table 3). Significantly more post-menopausal than pre-menopausal women thought of menopause as a time for freedom. Of the 22.1% of the sample who did not regard menopause as a problem, significantly more post-menopausal women said menopause was not a problem than did pre- and peri-menopausal women. Although less than 10% of women eagerly awaited menopause, significantly more pre-menopausal than post-menopausal women did. Although 20.2% of women associated femininity with menstruation, very few (3.3%) associated menopause with a loss of femininity, with no significant differences across menopausal status groups. Less than 15% of the sample regarded menopause as a nuisance with no menopausal status group differences. Significantly more pre- and peri- menopausal than post-menopausal women regarded menopause as the onset of old age (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Figure 2.

Menopausal attitudes by menopausal status (Percentages)

Table 3.

Attitudes toward menopause by menopausal status, n=1524 (Percentages)

| Percent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “What words would you use to describe menopause?” | Pre-menopausal | Peri-menopausal | Post-menopausal | P-values |

| Natural | 55 | 61 | 64 | .004 |

| Freedom | 16 | 23 | 32 | .000 |

| No problem | 10 | 14 | 35 | .000 |

| Eagerly awaited | 10 | 10 | 6 | .013 |

| Femininity loss | 3 | 7 | 4 | .129 |

| Fertility loss | 26 | 29 | 21 | .048 |

| Nuisance | 11 | 15 | 15 | .128 |

| Old age | 44 | 43 | 29 | .000 |

Factor Analyses

Factor analyses resulted in two clusters of attitudes associated with menstruation. The first factor consisted of negative attitudes (curse, nuisance, problem, and unnatural), and the second factor consisted of a positive attitude (sign of femininity and fertility) (Table 4). Three factors represented attitudes associated with menopause: negative attitudes (onset of old age and loss of fertility and femininity), positive anticipatory attitudes (freedom and eagerly awaited); and positive natural attitudes (natural, no problem, and not a nuisance) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Factor loadings for attitudes toward menstruation.

| Negative | Positive | |

|---|---|---|

| Curse | .567 | .011 |

| PMS relief | .169 | .302 |

| Femininity | −.083 | .812 |

| Fertility | −.085 | .815 |

| Nuisance | .710 | .061 |

| No problem | −.608 | −.113 |

| Natural | −.561 | .291 |

Values in boldface indicate large (> +.400 or < − .400) standardized factor loadings.

Table 5.

Factor loadings for attitudes toward menopause.

| Negative | Positive anticipatory | Positive natural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Freedom | .073 | .741 | .155 |

| Eagerly Awaited | −.059 | .739 | −.104 |

| Nuisance | .130 | −.046 | −.582 |

| Natural | .160 | −.072 | .736 |

| Old age | .656 | −.243 | −.097 |

| No problem | −.333 | .289 | .443 |

| Fertility loss | .784 | .099 | .153 |

| Femininity loss | .483 | .223 | −.288 |

Values in boldface indicate large (> +.400 or < − .400) standardized factor loadings.

Variables associated with attitudes toward menstruation

Using factors as dependent variables, we found that increasing age was significantly associated with a decline in negative attitudes toward menstruation (Table 6). Women who exercised were less likely to have negative menstrual attitudes, while women with menstrual cramps were more likely to express negative attitudes toward menstruation. More Asian women and women of other/mixed ethnicities expressed positive attitudes toward menstruation in contrast to European-Americans. Women who grew up outside of Hawai`i were more likely to have a positive attitude toward menstruation as were women with a higher education. Women who exercised and those who had had a hysterectomy also were more likely to have positive attitudes toward menstruation.

Table 6.

Results of backward stepwise linear regression on factor scores.

| Factors | Variables in final model | Unstandardized β and SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Menstruation: Negative attitudes: nuisance, curse, problem, unnatural | Age | −0.008 ±0.002 | 0.000 | |

| Sports/exercise | −0.173 ± 0.049 | 0.000 | ||

| Menstrual cramps | 0.399 ± 0.069 | 0.000 | ||

| 2. Menstruation: Positive attitudes: femininity, fertility | Ethnicity | 0.017 ± 0.006 | 0.005 | |

| Education | 0.110 ± 0.039 | 0.005 | ||

| Grow up | 0.120 ± 0.047 | 0.011 | ||

| Sports/exercise | 0.123 ± 0.051 | 0.016 | ||

| Hysterectomy | 0.167 ± 0.064 | 0.010 | ||

| 3. Menopause: Negative attitudes: old age, fertility loss, femininity loss | Education | 0.158 ± 0.040 | 0.000 | |

| Age | −0.012 ± 0.002 | 0.000 | ||

| Grow up | 0.088 ± 0.046 | 0.054 | ||

| Hot flashes | 0.111 ± 0.053 | 0.038 | ||

| 4. Menopause: Positive, anticipatory attitudes: freedom, eagerly awaited | Education | 0.127 ± 0.040 | 0.001 | |

| Age | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 0.000 | ||

| Grow up | 0.101 ± 0.046 | 0.026 | ||

| Menstrual cramps | −0.154 ± 0.072 | 0.033 | ||

| Hot flashes | 0.207 ± 0.053 | 0.000 | ||

| 5. Menopause: Positive, natural attitudes: natural, no problem, not a nuisance | Education | 0.116 ± 0.040 | 0.004 | |

| Age | 0.005 ± 0.002 | 0.039 | ||

| Menopausal status | 0.172 ± 0.041 | 0.000 | ||

| Grow up | 0.116 ± 0.046 | 0.011 | ||

| Menstrual cramps | −0.258 ± 0.072 | 0.000 | ||

| Hysterectomy | −0.273 ± 0.077 | 0.000 | ||

| Hot flashes | −0.193 ± 0.054 | 0.000 |

Variables associated with attitudes toward menopause

Using factors scores, we found that as women’s age increased, they were less likely to have a negative attitude toward menopause, but the higher their education, the more likely they were to have a negative attitude (Table 6). Having ever experienced hot flashes was also associated with a negative attitude. A positive, anticipatory attitude toward menopause was associated with increasing age, a higher education, and growing up outside of Hawai`i as well as having ever experienced a hot flash. Women who had menstrual cramps did not anticipate menopause positively. Increasing age and higher education were also associated with regarding menopause as a natural occurrence as were the latter stages of menopausal status and growing up outside of Hawai`i. Women who had had a hysterectomy or had experienced either menstrual cramps or hot flashes were less likely to regard menopause as natural.

Relationship between menstrual and menopausal attitudes

A bivariate correlation analysis suggested that a negative attitude toward menstruation was positively correlated with a negative attitude toward menopause (Table 7). A negative attitude toward menstruation was also positively correlated with a positive anticipation of menopause, but not with a positive attitude toward menopause as natural. A positive attitude toward menstruation was positively correlated with anticipating menopause and regarding it as natural. It was also positively correlated with a negative attitude toward menopause.

Table 7.

Pearson correlations for factor scores for menstrual and menopausal attitudes

| Negative Menopause | Positive Anticipatory Menopause | Positive Natural Menopause | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Menstruation | .05* | .20** | −.34** |

| Positive Menstruation | .39** | .12** | .17** |

p<0.05

p<0.01

DISCUSSION

Despite the tendency for the negative construction and medicalization of menstruation in Western cultures (Delaney et al. 1988; Linton 2007; Luke 1997) and the advocacy for menstrual suppression in mainstream media (Johnston-Robledo et al. 2006) and scholarly literature (Thomas and Ellertson 2000), more women in our study selected the word “natural” to describe menstruation than any other word or phrase. Correspondingly, 83% of young women (mean age of 24.3 years) regarded menstruation as natural in a smaller study (n=136) also conducted in Hawai`i (Morrison et al. 2010). Studies conducted in Spain and London found similarly positive outcomes with women stating that menstruation made them feel good, feel like a woman, was a way to get rid of toxins and that their body was in balance (Cheung and Free 2005; Sanchez-Borrego and García-Calvo, 2008).

Our study showed a comparable positive outcome for menopause. Almost 60% of our participants felt menopause was natural, a finding similar to a study of Ecuadorian nurses in which 94% over 40 years of age stated it was normal and not a problem (Leon et al. 2007). Although one-fifth of our sample associated menstruation with femininity, very few women associated menopause with a loss of femininity, a finding also consistent with the results from the Ecuador study (Leon et al. 2007).

We found that older women were less likely to express negative attitudes toward both menstruation and menopause, and more likely to express a positive, anticipatory attitude toward menopause and indicate that menopause was a positive, natural change. Similarly, a recent study found that 53 and 54-year old Swedish women regarded menopause as freedom, as did 20% of our participants of all ages, and were relieved not to be concerned about pregnancy (Lindh-Åstrand et al. 2007). No longer bleeding also has practical advantages, giving women more freedom (Kowalcek et al. 2005).

Women with a higher education held contrasting views. On the one hand, higher education was associated with a negative attitude toward menopause while on the other, it was associated with a positive attitude toward menstruation and a positive, anticipatory attitude toward menopause. Educated women are possibly seeking out information on menstruation and menopause and are therefore better-prepared and more knowledgeable, resulting in a more positive attitude (Lee 2002). However, knowing more about menopause would not preclude women from associating menopause with inescapable biological factors such as a loss of fertility and its relationship with advancing age.

Women in our study who played sports or exercised regularly held a positive view toward menstruation, complementing the findings of a recent study showing an association of regular exercise with significant diminishing of physical and psychological premenstrual symptoms (Jahromi et al. 2008). If women can mitigate the negative effects of menstruation with exercise, they may feel better about menstruation in general. However, we did not find an association between exercise and positive attitudes toward menopause.

In concordance with numerous national and international studies that have found racial/ethnic differences in women’s attitudes toward menstruation (Edelman et al. 2007; Glasier et al. 2003), we found non European-Americans, i.e. Asian women and those of other ethnicities, to have a more positive attitude toward menstruation compared with European-Americans. However, ethnicity was not associated with attitudes toward menopause. We found that women who grew up outside of Hawai`i were more likely to have a positive attitude toward both menstruation and menopause. Sommer et al. (1999) found not only race/ethnicity but level of acculturation to be significantly related to women’s construction of menopause. Women growing up outside of Hawai`i may have been exposed to different familial, cultural, and educational, influences during their formative years thereby influencing their positive attitudes toward menstruation and menopause. It appeared that where a woman grew up was more important than her ethnicity with regard to attitudes toward menopause in multi-ethnic Hilo, Hawai`i.

Women with menstrual cramps were less likely to regard menopause with positive attitudes, perhaps inferring that if they had physiological symptoms associated with menstruation they would also have them with menopause. Not surprisingly, women experiencing hot flashes described menopause with negative attitudes. An early outcome of SWAN was the finding that women with a negative attitude toward menopause were more likely to have menopausal symptoms (Avis et al. 1997), begging the question of which came first – the hot flashes or the attitude.

Motivated by McPherson and Korfine’s (2004) work which found an association between early menarcheal experience and attitudes toward menstruation, we found a clear association between attitudes toward menstruation and attitudes toward menopause. As hypothesized, we found that women with a negative attitude toward menstruation were more likely to have a negative attitude toward menopause. These women may be assuming that detrimental experiences with one aspect of the reproductive life cycle may predispose them to a similar outcome with the latter stage of the reproductive cycle. This does not contradict the finding that having negative attitudes toward menstruation may also predispose women to anticipate menopause positively because menopause can remove physical or psychological burdens associated with menstruation.

In addition, the cluster of positive attitudes (sign of femininity and fertility) was correlated with the negative factor score for menopause (old age, loss of fertility, and femininity), perhaps reflecting Western societal attitudes toward women and aging. On the other hand, women who had a positive attitude toward menstruation tended to also positively anticipate menopause and regard it as natural. This seems contradictory, but reflects the complexity of meaning and experience associated with both menstruation and menopause. It has been suggested that women’s attitudes toward menopause evolve as they progress through the transition (Fu et al. 2003) but our study suggests that women are already pre-disposed toward how they view menopause based on their attitudes toward menstruation, positive or negative.

Our study had several limitations that could be addressed in future research. For example, 85% of women reported the experience of menstrual cramps, but we did not ask about the timing (age) or severity of cramps. With respect to birth control, only 11% and 2.4% of our sample were using oral contraception and Depo-Provera, respectively, but this may have altered their experience and affected their attitudes toward menstruation. Pregnancy status was not assessed, therefore pregnant women may have been categorized incorrectly (as peri- or post-menopausal) based on date of last menstrual period. Another possible limitation was that our survey questions were based on recall, although a recent study found postmenopausal women to have very accurate recall of their reproductive life history (Lucas et al. 2008). A recent study found that reporting bias may be responsible for the ethnic difference found in reporting hot flashes (Brown et al. 2009), a legitimate consideration for our study. Despite the apparent representativeness of our sample with regard to ethnicity, our study may have suffered from participation bias, given the moderately low participation rate.

Although our study found that ethnicities other than European-Americans were more likely to report what we describe as negative menstrual and menopausal attitudes (for example menopause as the onset of old age), in future studies, greater attention needs to be given to cultural constructions from the perspective of the researchers as well as the respondents. In Asian cultures, the onset of old age and its attendant respect may be a positive attitude in contrast to the European-American construction. Therefore, our study might suffer from researcher bias rather than reporting bias, both of which are inherent limitations in using surveys. Also, for future studies, a quantitative study such as this would benefit from in-depth qualitative analysis to decipher more clearly some of the relationships found, especially with respect to the construction of womanhood and the meaning of aging.

CONCLUSION

Overall, women had positive attitudes toward menstruation and menopause. Age, rather than menopausal status, was significantly associated with negative attitudes toward menstruation and menopause, as well as positive, anticipatory attitudes toward menopause.. Physically active women were more likely to have positive attitudes toward menstruation, and highly educated women were more likely to have positive attitudes toward both menstruation and menopause, but also more likely to have negative attitudes toward menopause. Education, age, hot flashes, and where a woman grew up, but not ethnicity, were associated with attitudes toward menopause. Correlations were observed between attitudes toward menstruation and attitudes toward menopause, whether they were positive or negative. Because women may be predisposed to formulate their attitudes toward menopause based on their attitudes toward menstruation, receiving constructive messages and optimistic support at the beginning of women’s reproductive life history seems imperative. Research highlighting the beneficial aspects of menstruation and menopause would be an affirmative contribution to women’s health.

Acknowledgments

Mahalo to the women of Hilo for participating in our survey. The thoroughness and insightful comments of the reviewers were much appreciated. Thanks to our research staff for all their hard work.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Minority Biomedical Research Support Program, grant S06 GM08073-34.

Footnotes

In concordance with the American Association of Physical Anthropologists (AAPA) Statement on Biological Aspects of Race (http://physanth.org/association/position-statements/biological-aspects-of-race/?searchterm=race), a position statement outlining why the term ‘race’ is scientifically problematic, we asked our participants to identify their ethnicity rather than race. However, we have used the term ‘race’ in this manuscript in reference to other researchers work to acknowledge their use of the term.

The choice given in the questionnaire was “relief from PMS” using the acronym only. Because we did not spell out nor give the clinical definition for ‘premenstrual syndrome’, the intention in the questionnaire was for the colloquial usage of ‘PMS’ referring to symptoms felt around the time of menstruation. Thus, the accurate acronym for premenstrual symptoms, PMSx, is used in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Lynn A. Morrison, Department of Anthropology University of Hawai`i at Hilo 200 W. Kawili St. Hilo, HI 96720 lmorriso@hawaii.edu Tel: 808-974-7697.

Lynnette L. Sievert, Department of Anthropology Machmer Hall University of Massachussetts- Amherst Amherst, MA 01003 leidy@anthro.umass.edu.

Daniel E. Brown, Department of Anthropology University of Hawai`i at Hilo 200 W. Kawili St. Hilo, HI 96720 dbrown@hawaii.edu.

Nichole Rahberg, Department of Anthropology University of Hawai`i at Hilo 200 W. Kawili St. Hilo, HI 96720 monarch422@yahoo.com.

Angela Reza, Department of Anthropology Machmer Hall University of Massachussetts- Amherst Amherst, MA 01003 angelareza@yahoo.com.

REFERENCES

- Avis NE, Kaufert PA, Lock M, McKinlay SM, Vass K. The evolution of menopausal symptoms. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;7:17–32. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, McKinlay SM. Psychosocial, behavioral, and health factors related to menopause symptomatology. Womens Health. 1997;3(2):103–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avis NE, Stellato R, Crawford S, Bromberger J, Ganz P, Cain V, Kagawa-Singer M. Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:345–356. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles C. Measure of attitude toward menopause using the semantic differential model. Nurs Res. 1986;35:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DE, James GD, Nordloh L. Comparison of factors affecting daily variation of blood pressure in Filipino-American and Caucasian nurses in Hawai`i. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1998;106(3):373–383. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199807)106:3<373::AID-AJPA9>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DE, Sievert LL, Aki SL, Mills PS, Etrata MB, Paopao RNK, James GD. The effects of age, ethnicity, and menopause on ambulatory blood pressure: Japanese-American and Caucasian school teachers in Hawai`i. Am J Hum Bio. 2001;13:486–493. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DE, Sievert LL, Morrison LA, Reza AM, Mills PS. Do Japanese American women really have fewer hot flashes than European Americans? The Hilo Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2009;16:870–876. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31819d88da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung E, Free C. Factors influencing young women’s decision making regarding hormonal contraceptives: a qualitative study. Contraception. 2005;71:426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley AJ, Stokes-Lampard HJ, MacArthur C. Exercise to reduce vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms: A review. Maturitas. 2009;63:176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney J, Lupton MJ, Toth E. The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. Chicago: University of Illinois Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Del Saz-Rubio MM, Pennock-Speck B. Constructing female identity through feminine hygiene TV commercials. J Pragmat. 2009;41:2535–2556. [Google Scholar]

- Donati S, Cotichini R, Mosconi P, Satolli R, Colombo C, Liberati A, Mele A. Menopause: Knowledge, attitude and practice among Italian women. Maturitas. 2009;63:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman A, Lew R, Cwiak C, Nichols M, Jensen J. Acceptability of contraceptive-induced amenorrhea in a racially diverse group of US women. Contraception. 2007;75:450–453. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruzzetti F, Paoletti AM, Lombardo M, Carmignani A, Genazzani AR. Attitudes of Italian women concerning suppression of menstruation with oral contraceptives. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13:153–157. doi: 10.1080/13625180701800672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S-Y, Anderson D, Courtney M. Cross-cultural menopausal experience: Comparison of Australian and Taiwanese women. Nurs Health Sci. 2003;5:77–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallicchio L, Miller S, Zacur H, Flaws JA. Race and health-related quality of life in midlife women in Baltimore, Maryland. Maturitas. 2009;63:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon L, Ekstrom B. Attitudes towards menopause: the influence of sociocultural paradigms. Psychol Women Q. 1993;17:275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Glasier AF, Smith KB, van der Spuy ZM, Ho PC, Cheng L, Dada K, Wellings K, Baird DT. Amenorrhea associated with contraception: an international study on acceptability. Contraception. 2003;67(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson S, Jackowski RM, Kirking DM. Women’s trust in and use of information sources in the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvas L. Positive aspects of menopause: A qualitative study. Maturitas. 2001;39:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi MK, Gaeini A, Rahimi Z. Influence of a physical fitness course on menstrual cycle characteristics. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24:659–662. doi: 10.1080/09513590802342874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston-Robledo I, Barnack J, Wares S. “Kiss your period good-bye”: Menstrual suppression in the popular press. Sex Roles. 2006;54:353–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalcek I, Rotte D, Banz C, Diedrich K. Women’s attitudes and perceptions towards menopause in different cultures: Cross-cultural and intra-cultural comparison of pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women in Germany and in Papua New Guinea. Maturitas. 2005;51:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg FL. Hot flashes: epidemiology and physiology. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;592:52–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb30316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Health and sickness: the meaning of menstruation and premenstrual syndrome in women’s lives. Sex Roles. 2002;46(1–2):25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Leidy L, Canali C, Callahan W. The medicalization of menopause: implications for recruitment of study participants. Menopause. 2000;7(3):193–199. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon P, Chedraui P, Hidalgo L, Ortiz F. Perceptions and attitudes toward the menopause among middle age women from Guayaquil, Ecuador. Maturitas. 2007;57:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindh-Åstrand L, Brynhildsen J, Hoffmann M, Liffner S, Hammar M. Attitudes towards the menopause and hormone therapy over the turn of the century. Maturitas. 2007;56:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton D. Men in menstrual product advertising – 1920–1949. Women Health. 2007;46:99–114. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas R, Azevedo A, Barros H. Self-reported data on reproductive variables were reliable among postmenopausal women. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:945–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke H. The gendered discourses of menstruation. Social Alternatives. 1997;16:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan AH, Broadbent JL, Taylor AW. Continuing decline in hormone therapy use: population trends over 17 years. Climacteric. 2009;12:122–130. doi: 10.1080/13697130802666251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson ME, Korfine L. Menstruation across time: menarche, menstrual attitudes, experiences, and behaviors. Womens Health Issues. 2004;14:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison LA, Larkspur L, Calibuso MJ, Brown S. Women’s attitudes about menstruation and associated health and behavioural characteristics. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:90–100. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, Signorielli N. Reporter sex and newspaper coverage of the adverse health effects of hormone therapy. Women Health. 2007;45:1–15. doi: 10.1300/J013v45n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten B, Wood V, Kraines RJ, Loomis B. Women’s attitudes toward the menopause. Vita Humana. 1963;6:140–151. doi: 10.1159/000269714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftos M, Jackson D, Mannix J. Idealized versus tainted femininity: discourses of the menstrual experience in Australian magazines that target young women. Nurs Inq. 1998;5:174–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1800.1998.530174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts T-A. Female trouble: the menstrual self-evaluation scale and women’s self-objectification. Psychol Women Q. 2004;28:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rose JG, Chrisler JC, Couture S. Young women’s attitudes toward continuous use of oral contraceptives: The effect of priming positive attitudes toward menstruation on women’s willingness to suppress menstruation. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29:688–701. doi: 10.1080/07399330802188925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Anderson G, Prentice GL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Borrego R, García-Calvo C. Spanish women's attitudes towards menstruation and use of a continuous, daily use hormonal combined contraceptive regimen. Contraception. 2008;77(2):114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert LL, Waddle D, Canali K. Marital status and age at natural menopause: considering pheromonal influence. Am J Human Biology. 2001;13:479–485. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert LL, Espinosa-Hernandez G. Attitudes towards menopause in relation to symptom experience in Puebla, Mexico. Women Health. 2003;38:93–106. doi: 10.1300/J013v38n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert LL, Morrison LA, Reza AM, Brown DE, Kalua E, Tefft HAT. Age-related differences in health complaints: The Hilo Women’s Health Study. Women Health. 2007;45(3):31–51. doi: 10.1300/J013v45n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert LL, Saliba M, Reher D, Sahel A, Hoyer D, Deeb M, Obermeyer CM. The medical management of menopause: A four-country comparison care in urban areas. Maturitas. 2008;59:7–21. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer B, Avis N, Meyer P, Ory M, Madden T, Kagawa-Singer M, Mouton C, O’Neill Rasor N, Adler S. Attitudes toward menopause and aging across ethnic/racial groups. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:868–875. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199911000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SL, Ellertson C. Nuisance or natural and healthy: should monthly menstruation be optional for women? Lancet. 2000;355:922–924. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)11159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utian WH, Boggs PP. The North American Menopause Society 1998 Menopause Survey Part 1: Postmenopausal women’s perceptions about menopause and midlife. Menopause. 1999;6:122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner PJ, Kuhn S, Petry LJ, Talbert FS. Age differences in attitudes toward menopause and estrogen replacement therapy. Women Health. 1995;23:1–16. doi: 10.1300/j013v23n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worcester N. Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT): Getting to the heart of the politics of women’s health? NWSA J. 2004;16:56–69. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Geneva: WHO; Research on the Menopause. WHO Technical Report Series No. 670. 1981 [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Geneva: WHO; Research on the Menopause in the 1990s. WHO Technical Report Series No. 866. 1996 [PubMed]