The role that the adaptive immune system has in the control of blood pressure and pathogenesis of hypertension has been of interest to investigators for several decades. Early evidence on this subject in humans showed an enhanced T lymphocyte activation during malignant hypertension 1 and also implicated a role for B lymphocytes since autoantibody production was elevated in hypertensive patients 2. In addition, early studies in experimental animal models demonstrated hat thymectomy cured hypertension in New Zealand Black Mice 3 or that renal induced hypertension in rats was associated with thymic hypertrophy 4. Moreover, the transplantation of thymus extracts from Wistar Kyoto Rats or immunosuppressive therapy reduced blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats 5,6. Although these studies strongly implicated immune system dysfunction as an important contributor to the development of hypertension, interest in the role for the immune system in blood pressure control appeared to wane.

More recently, an interest in the role of the immune system in the development of hypertension has been renewed. In the past several years it is has been difficult to miss the growing body of evidence supporting a mechanistic role for the adaptive immune system. Harrison’s group recently demonstrated that angiotensin II (AngII) dependent hypertension requires T cells, but not B cells using RAG1−/− knockout mice 7 and Crowley’s group similarly found an important role for adaptive immunity in AngII mediated hypertension using severe combined immunodeficient mice 8. There have also been several studies showing that inhibiting B and T cell proliferation with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) lowers blood pressure in experimental animal models of hypertension such as the Dahl salt-sensitive rat 9. In humans, there is not as much direct evidence available supporting a role for adaptive immunity in the pathophysiology of hypertension; however, a small study in 8 patients with essential hypertension (but also rheumatoid arthritis and/or psoriasis) demonstrated that treatment with MMF lowered blood pressure 10. Taken together, this growing body of literature supports a potentially important physiological role for the immune system in the pathophysiology of hypertension and there is continued interest in understanding the cellular and molecular mediators of these pathways.

One of the major mediators of immune system function is inflammatory cytokines. Although this is an oversimplification, multiple subsets of T cells produce a variety of inflammatory cytokines that function to promote humoral immunity (T helper 2), cell mediated immunity (T helper 1), immune suppression (T regulatory), or the newly described T helper 17 cytokines implicated in normal epithelial and mucosal barriers as well as tissue inflammation and injury. In humans, there is a direct correlation between circulating and tissue levels of T helper 1 cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), with blood pressure. Despite these associations, the physiological role for cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 in the development of hypertension remains unclear. Pharmacological therapies used to reduce the biological activity of TNF-α have had mixed success in reducing/preventing hypertension in experimental animal models and there are limited available pharmacological tools to manipulate IL-6. Therefore, there is a clear need for experiments designed to better understand how specific inflammatory cytokines contribute to hypertension.

Previous work from Brands et al. began to investigate the mechanisms by which IL-6 contributes to AngII hypertension. Their data showed that hypertension caused by high salt diet and AngII was blunted in mice lacking a functional gene for IL-6 11; however, mineralocorticoid dependent hypertension was not affected 12. While these studies clearly pointed to a role for IL-6 in the development of AngII hypertension, whether the protection against AngII hypertension in IL-6 knockout mice was dependent on renal hemodynamic changes was not directly addressed. In this issue of Hypertension, Brands et al 13 takes an important step in the direction of understanding the mechanism by which IL-6 contributes to AngII hypertension. Similar to their initial work, blood pressure in the current study was lower in IL-6 knockout mice given AngII. However, different from results obtained in the former study, the hypertension was completely abolished rather than only blunted. This is most likely because the animals from the former study were maintained on a high salt diet in addition to the AngII. The reason that AngII is able to increase pressure in IL-6 knockout mice maintained on a high salt diet is not clear, but suggests that some permissive factors or alternative pathways are present during high salt intake. In addition, the inability to suppress AngII production is known to result in salt-sensitive hypertension. Nevertheless, the blood pressure data from both studies is relevant because in each case they illustrate an important contribution of IL-6 to AngII mediated hypertension.

The major advance made in the present study comes from data collected during chronic measurements of renal blood flow (RBF) in conscious mice. These results show that AngII dose dependently produces a sustained decrease in RBF in wild type mice. Surprisingly, the RBF response to AngII in IL-6 knockout mice was similar to the wild type mice, even as the wild type animals exhibited the expected hypertension that was otherwise absent in the IL-6 knockout mice. The authors go further to show that afferent arteriolar constriction in response to AngII is the same between wild type and IL-6 knockout mice, at least under control conditions. These data are provocative because they raise perhaps as many questions as are answered related to the role that IL-6 plays in AngII hypertension. The author’s main conclusion that renal vasoconstriction in response to AngII is not sufficient to cause hypertension in the absence of IL-6 begs the question what are the factors and pathways mediated by IL-6 to promote hypertension? Assuming that glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is reduced to the same degree as RBF, one would predict not only that sodium reabsorption has to be suppressed, but also that there is an active natriuresis occurring in the IL-6 knockout mice infused with AngII.

The authors speculate, based on their data showing that AngII increased JAK2/STAT3 in the renal cortex of wild type mice but not IL-6 knockout mice, that this signaling pathway may be important for tubular sodium reabsorption. It will be informative to determine whether JAK/STAT signaling and epithelial sodium channel expression (ENaC) are decreased specifically in the cortical collecting ducts of IL-6 knockout mice infused with AngII. Some evidence suggests that AngII in combination with IL-6 increases STAT3 signaling in proximal tubular cells and that IL-6 increases ENaC expression in cultured collecting duct cells 14,15. If this is the case, one could also speculate that decreased ENaC expression in IL-6 knockout mice might counter the increased drive for sodium reabsorption created by reduced meduallary blood flow in response to AngII.

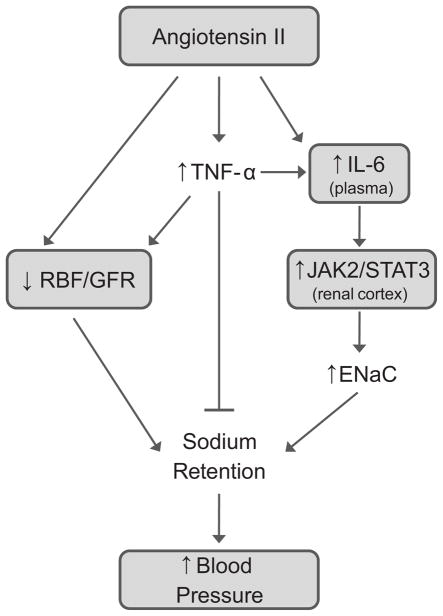

Even if these speculative changes in tubular reabsorption of sodium are occurring in IL-6 knockout mice, they would likely not be enough to offset the reduced filtered load of sodium created by the predicted decrease in GFR. Therefore, another factor would have to be activated to promote the natriuresis. One possibility is the cytokine TNF-α. Work from Ferreri’s group and evidence from Majid’s laboratory suggest that TNF-α (stimulated by AngII) has potential natriuretic effects in the renal tubules 16,17. Perhaps in the absence of IL-6, the natriuretic actions of TNF-α are enhanced. An enhanced TNF-α mediated natriuresis coupled with the possible reduction in renal cortical ENaC may be enough to overcome the renal hemodynamic effects of AngII and TNF-α (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed role for inflammatory cytokines in angiotensin II dependent hypertension. Direct renal vascular effects of angiotensin II (and TNF-α) reduce renal blood flow (RBF) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) to promote sodium retention. IL-6, stimulated directly by angiotensin II or indirectly through an angiotensin II mediated increase in TNF-α, activates JAK2/STAT3 signaling in the renal cortex which augments ENaC expression and sodium retention. The natriuretic actions of TNF-α partially counter the effects of impaired renal hemodynamics and IL-6 mediated increases in tubular reabsorption of sodium. The shaded boxes represent relationships that are directly tested, or supported indirectly as an association, in Brands et al 13.

It should be noted that a role for the renal vasculature cannot be completely dismissed. One of the limitations acknowledged by the authors is that, although the RBF response to AngII is similar in wild type and IL-6 knockout mice, the RBF response is apparently blunted in the IL-6 knockout mice, especially over the last three days of AngII infusion. Whether this modest difference is physiologically important will be difficult to discern. In order to bolster the idea that AngII hypertension is not dependent upon renal vascular effects of IL-6, the authors included data showing that afferent arteriolar constriction in response to increasing concentrations of AngII is not different between wild type and IL-6 knockout mice. However, this relationship will need to be tested in knockout and wild-type mice chronically infused with AngII to further solidify this claim. These types of experiments will need to be performed in order to more completely understand how IL-6 contributes to AngII mediated hypertension.

The mechanisms by which IL-6 contribute to the development of AngII are still not resolved. In addition to speculation about renal vascular changes and tubular sodium handling, it is possible that IL-6 may be necessary to drive the well known increase in oxidative stress caused by AngII. Furthermore, even though the present work by Brands et al is focused on renal mechanisms, the possibility of extra renal factors playing a role remains, including direct effects of IL-6 on the peripheral vasculature or in the central nervous system. This study by Brands et al provides important new information that allows the reader to ask the next series of questions that will need to be answered in order to understand the physiological role of this important inflammatory mediator in AngII hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

None

Sources of Funding

M.J. Ryan is supported by the National Institutes of Health, NHLBI awards HL085907, HL085907s3, and HL092284

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Gudbrandsson T, Hansson L, Herlitz H, Lindholm L, Nilsson LA. Immunological changes in patients with previous malignant essential hypertension. Lancet. 1981;1:406–408. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91790-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristensen BO. Increased serum levels of immunoglobulins in untreated and treated essential hypertension. I. Relation to blood pressure. Acta Med Scand. 1978;203:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1978.tb14830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svendsen UG. Spontaneous hypertension and hypertensive vascular disease in the NZB strain of mice. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1977;85:548–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1977.tb03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatelain RE, Vessey AR, Ferrario CM. Lymphoid alterations and impaired T lymphocyte reactivity in experimental renal hypertension. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;95:737–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khraibi AA, Norman RA, Jr, Dzielak DJ. Chronic immunosuppression attenuates hypertension in Okamoto spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:H722–H726. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.247.5.H722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ba D, Takeichi N, Kodama T, Kobayashi H. Restoration of T cell depression and suppression of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) by thymus grafts or thymus extracts. J Immunol. 1982;128:1211–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowley SD, Song YS, Lin EE, Griffiths R, Kim HS, Ruiz P. Lymphocyte responses exacerbate angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1089–R1097. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00373.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattson DL, James L, Berdan EA, Meister CJ. Immune suppression attenuates hypertension and renal disease in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. Hypertension. 2006;48:149–156. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000228320.23697.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrera J, Ferrebuz A, MacGregor EG, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:S218–S225. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DL, Sturgis LC, Labazi H, Osborne JB, Jr, Fleming C, Pollock JS, Manhiani M, Imig JD, Brands MW. Angiotensin II hypertension is attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H935–H940. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00708.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sturgis LC, Cannon JG, Schreihofer DA, Brands MW. The role of aldosterone in mediating the dependence of angiotensin hypertension on IL-6. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1742–R1748. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90995.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brands MW, Banes-Berceli AKL, Inscho EW, Al-Azawi H, Allen AJ, Labazi H. Interleukin-6 Knockout Prevents Angiotensin II Hypertension: Role of Renal Vasoconstriction and JAK2/STAT3 Activation. Hypertension. 2010;x:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li K, Guo D, Zhu H, Hering-Smith KS, Hamm LL, Ouyang J, Dong Y. Interleukin-6 stimulates epithelial sodium channels in mouse cortical collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R590–R595. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00207.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satou R, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Katsurada A, Navar LG, Kobori H. Costimulation with angiotensin II and interleukin 6 augments angiotensinogen expression in cultured human renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F283–F289. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00047.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahid M, Francis J, Matrougui K, Majid DS. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in natriuretic response to systemic infusion of nitric oxide synthase inhibitor in anesthetized mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F217–F224. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00611.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreri NR, Zhao Y, Takizawa H, McGiff JC. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-angiotensin interactions and regulation of blood pressure. J Hypertens. 1997;15:1481–1484. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]