Abstract

Delirium is common, deadly, and costly in people with dementia. The purpose of this pilot study was to test the feasibility of the computerized decision support component of an intervention strategy—Early Nurse Detection of Delirium Superimposed on Dementia—designed to improve nurse assessment and detection of delirium superimposed on dementia. This pilot study enrolled and followed 15 individuals with dementia (mean age = 83, mean admission Mini-Mental State Examination score = 14.8) and their caregivers daily for the duration of their hospitalization. Results indicated 100% adherence by nursing staff on the delirium assessment decision support screens and 75% adherence on the management screens. Despite the prevalence and severity of delirium in people with dementia, there are currently no published reports of the use of the electronic medical record in delirium detection and management. Success of this effort may encourage similar use of information technology in other settings.

Delirium occurs in more than half of hospitalized older adults with dementia, is expensive to the health care system, and may be deadly to those who experience it (Fick, Kolanowski, Waller, & Inouye, 2005). Delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD) leads to increased mortality, nursing home placement, early rehospitalization, and further functional decline (Fick, Agostini, & Inouye, 2002; Fick et al., 2005; Inouye, 2006). Delirium is costly, with annual costs attributable to delirium ranging from $16,303 to $64,421 per patient, and the national burden of delirium on the health care system costing up to $152 billion annually (Leslie, Marcantonio, Zhang, Leo-Summers, & Inouye, 2008).

Despite the fact that delirium occurs most commonly in people with dementia and the substantial mortality rate associated with this problem, it is frequently unrecognized or misdiagnosed in older adults with dementia (Fick, Kolanowski, & Waller, 2007; Inouye, 2006). In several studies, delirium went unrecognized by nurses and physicians in more than half of the patients (Fick et al., 2007; Inouye, 1993). Nurses are essential to early detection, as they are at the bedside and are often the first health professionals to observe changes in patients’ mental status. In other published work, the authors have shown that DSD is more likely than delirium alone to be underrecognized and to be associated with inappropriate and excessive use of central nervous system medications and increased costs (Fick et al., 2005, 2007; Fick & Foreman, 2000). When patients with dementia do have an acute change in cognition, it may be missed, misattributed to dementia alone, or labeled as sundowning (Fick & Foreman, 2000).

Several studies have shown that in addition to underrecognizing delirium, nurses typically use psychoactive medication as their first line of management for delirium in people with dementia. When nurses were asked about management strategies in a study using standardized case vignettes, 32% stated they would call the physician to request psychoactive medication for a patient with hypoactive delirium alone and 63% would call for psychoactive medication for a patient with hyperactive DSD (Fick et al., 2007). It is not good practice to medicate a delirious patient with a sedative or psychoactive drug as the first response if a medical condition, such as pneumonia or urinary tract infection, is causing the increased confusion. This is especially concerning for those exhibiting the hypoactive form of delirium (Fick & Foreman, 2000; Voyer, Richard, Doucet, & Carmichael, 2009). These studies suggest that a method to increase nurses’ awareness of DSD and to facilitate and support nursing assessment and improved nonpharmacological management of DSD is crucial for improving care for hospitalized patients with dementia.

Nursing education about delirium, facilitation of the recognition of delirium in the context of the nurse workload, and unit-based support and feedback for the management of delirium are all necessary to improve outcomes in people with DSD. However, none of these interventions are sufficient by themselves to effect a meaningful and sustained change in clinicians’ practice behaviors (Oxman, Clarke, & Stewart, 1995). Increasing evidence indicates that the electronic medical record (EMR) and personal and timely feedback to the provider are effective in facilitating timely recognition and appropriate management in conditions such as DSD (DesRoches et al., 2008). Although the body of work on delirium prevention is growing, currently no reports have been published on the use of the EMR in delirium detection and management interventions tailored specifically to people with dementia. This study was designed to address this gap in evidence by translating standard clinical tools into EMR interventions engineered to support nurses’ early detection and improved management of DSD.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this pilot study was to investigate the feasibility of the computerized decision support component of a multicomponent intervention strategy called Early Nurse Detection of Delirium Superimposed on Dementia (END DSD). END DSD consists of four components:

Nursing education regarding detection and management of DSD (DSD Educational Modules).

Computerized decision support through delirium decision support screens for delirium assessment and detection and nonpharmacological management modules targeted toward nurses and facilitated with the EMR. This intervention is designed to improve both nurse assessment and detection of delirium and nonpharmacological management of DSD.

A unit champion, who will be used to promote or persuade other nurses to implement the innovation.

A feedback mechanism to individual nurses on each intervention unit to further facilitate assessment and management of DSD.

METHOD

Study Design and Procedures

This was a prospective, cohort, pilot study design enrolling and following 15 consecutively admitted patients with dementia and their caregivers for the duration of their hospitalization to test the feasibility of the computerized delirium support screens. We were specifically interested in (a) our ability to enroll and follow participants, (b) nurse adherence to the screen, (c) usability of the screens, and (d) narrative feedback from nursing staff, patients, and family caregivers. The study protocol was reviewed and approved for human subjects in research protection by the site’s institutional review board.

Setting and Sample

The study took place on one adult medical-surgical unit in an acute care hospital that provides care to most of the central Pennsylvania region where it is located. This facility has 200 beds, three medical-surgical units, and two intensive care units. We obtained informed consent and assent from both patients and their caregivers. Eligible patients were those age 65 and older, admitted to the study unit, and met the criteria for dementia. Exclusion criteria were hospitalized less than 24 hours; significant neurological or neurosurgical disease associated with cognitive impairment; subdural hematoma; head trauma or known structural brain abnormalities; nonverbal and unable to communicate due to severe dementia, aphasia, intubation, or terminal illness; and/or no family caregiver to interview. Family members/caregivers were identified for the study by using the next-of-kin assessment of the best proxy instrument, which assessed who had regular contact with the patients with dementia. (The instrument is available from the corresponding author on request.) Nurse users were RNs and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) assigned to the study unit.

Measures

To measure dementia, the responsible family caregiver was interviewed using two instruments: the Modified Blessed Dementia Rating Scale (MBDRS; Blessed, Tomlinson, & Roth, 1968) and the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR; Hughes, Berg, Danziger, Coben, & Martin, 1982). The MBDRS is an 8-item scale for informants based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, revised (DSM-III-R), criteria for dementia; it has been validated in earlier studies. It discriminates between individuals with and without dementia by establishing premorbid cognitive functioning. To qualify for the study, participants must have scored 3 or higher on the MBDRS (indicating a positive dementia screen), with symptoms evident for at least 6 months. The CDR is a 5-point scale in which a score of 0 indicates no dementia and scores ranging from 0.5 to 3 (severe dementia) indicate stages or degrees of dementia severity. It has an overall kappa of 0.9, a sensitivity of 0.74, and a specificity of 0.81 (Hughes et al., 1982).

Daily assessments of delirium were conducted using a structured interview consisting of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), observation, and the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM; Inouye et al., 1990). The MMSE was administered as part of the delirium assessment to evaluate whether features of the CAM were present or absent.

The MMSE is a 30-item cognitive screen that measures orientation, memory, attention, and language with scores ranging from 0 to 30; higher scores indicate greater cognitive function. The test-retest reliability of the MMSE ranges from 0.56 to 0.98, and its interrater reliability has not been less than 0.82 (Tombaugh & McIntyre, 1992).

The CAM is a standardized screening algorithm allowing people without formal training to quickly and accurately identify delirium. The CAM has four features: (1) acute onset and fluctuating course, (2) inattention, (3) disorganized thinking, and (4) altered level of consciousness. Participants are scored as having subsyndromal (partial) delirium if they exhibit any two features and as having full delirium if they exhibit features 1 and 2 and either 3 or 4. The CAM was validated against geriatric psychiatrists’ ratings using DSM-III-R criteria and has been shown to have a sensitivity between 94% and 100% and a specificity between 0.90 and 0.95 (Inouye et al., 1990). The CAM has also been validated in people with dementia. Studies have shown the utility of daily CAM use in identifying delirium and its waxing and waning states (Inouye et al., 1990). Delirium was recorded daily by research assistants (RAs) in this study as no delirium (0), subsyndromal delirium (1), or full delirium (2). RAs were trained in all instruments; quarterly reliability training achieved greater than 90% reliability on all paired ratings for the CAM and MMSE.

Enrollment and Data Collection Procedures

We reviewed the names and diagnoses of all eligible patients who were admitted to the unit each day from the hospital admission log and who met our broad inclusion criteria by age and diagnosis. For each newly admitted patient the project director (PD) used the initial screen to determine eligibility for the study. If the potential participant met all initial review criteria, the PD then contacted the responsible party for verbal consent to complete the screen using the CDR (responsible party), the MBDRS (responsible party), the CAM (patient), and MMSE (patient). To protect patients’ autonomy, we also determined decisional capacity for consent with a set of eight questions. (These questions are available from the corresponding author on request.) We obtained dual consent (patients and caregivers) from all participants who met the following criteria: MMSE score of 18 or higher and score of 6 of 8 on the study-understanding tool. For participants who scored less than 18 on the MMSE, we obtained consent from the responsible party only and daily assent from the patient.

Satisfaction surveys were administered at discharge or by follow-up telephone calls with the family caregiver and patient, if available and able to talk on the telephone.

Nurse Adherence

We measured overall nurse adherence to the screens and usability by obtaining data from the hospital Information Services staff. Data included the number of nurses who used the screens during the pilot study, time in minutes between use of screens, and any narrative comments from the nurses in the EMR. Narrative comments were also obtained from the RAs’ field notes while the nurses were using the screens (usability). Nurse participants were not identified in the data collection procedures.

DSD Educational Modules

To pilot test the educational modules, we invited all unit-based nursing personnel to participate in a slide presentation that focused strongly on clinical assessment of delirium using the CAM and on management of DSD. The educational module was delivered four times on all three shifts in 60-minute sessions. We also showed them the mock computer screens during the sessions. At the sessions, we distributed laminated cards listing delirium assessment and management tips, as well as a case study of assessment and management of delirium. We also included information from the How to Try This article and video (Fick & Mion, 2008). Nurses received one continuing education unit, and nonlicensed personnel were given a certificate of participation. Attendance at the educational sessions was tracked while maintaining staff confidentiality.

Computerized Decision Support Intervention Screens

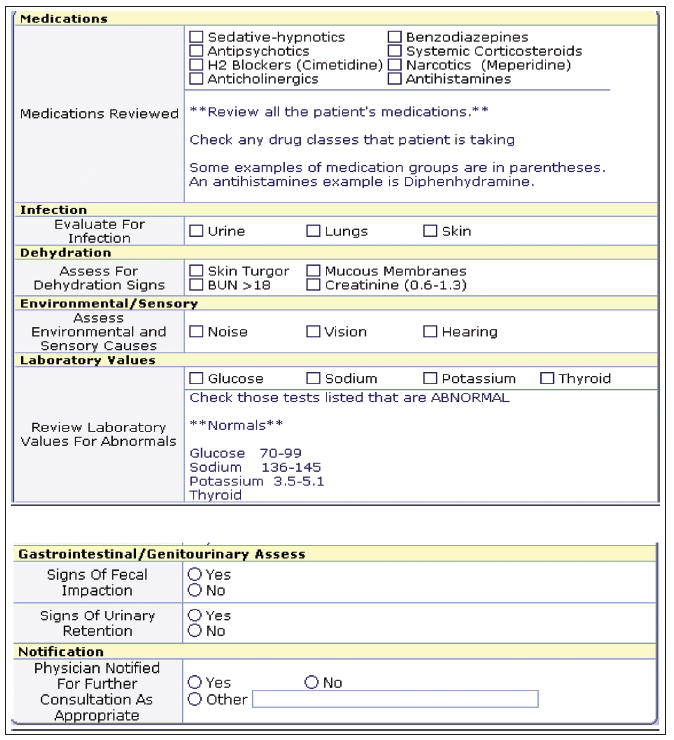

All intervention patients had three computer decision support screens activated by the RAs on study enrollment: (a) the CAM assessment screen, (b) the delirium-associated factors screen (Figure 1), and (c) the management screen. The CAM assessment screen required the nurse to document an assessment for delirium every shift. The electronic version of the CAM had all features of the CAM and was scored the same as the original CAM using underlying programming to notify the nurse of a positive screen.

Figure 1.

Decision support screen for assessment of factors associated with delirium. BUN = blood urea nitrogen.

The screen for assessment of the causes of delirium (Figure 1) pulled any available associated data from other parts of the electronic chart for the nurse to view, including electrolyte values (sodium, glucose, hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine, potassium), available pain ratings, fall rating scores, activity level, intake and output, urine and bowel care, oxygen saturation levels, and available sensory aid information. These data were only pulled into the delirium screen if they were available elsewhere in the record. They were blank if not available and were left for the nurse to assess or document in the record. All three screens were activated every day for all enrolled patients and were present for the nurses to use every shift (although not required) regardless of whether the initial CAM screen was positive for delirium.

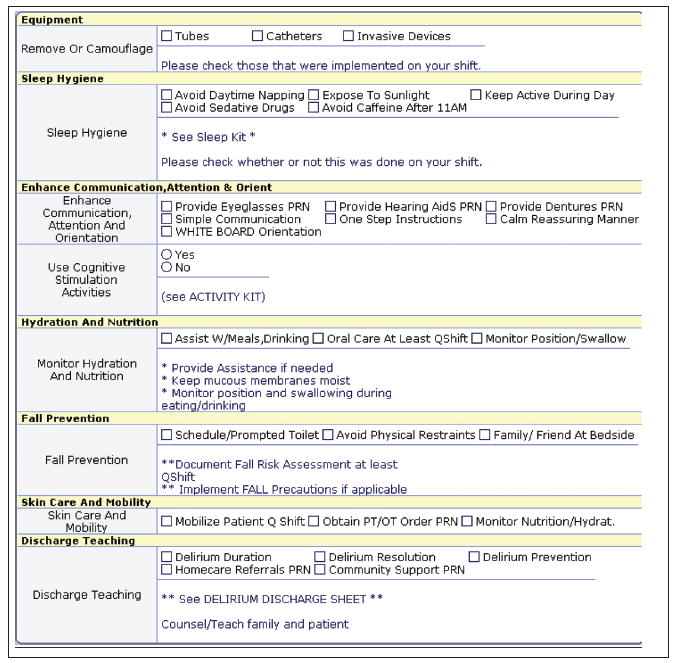

The computer screen for the management of delirium (Figure 2) provided decision support for individualized management strategies, support for sleep hygiene, and a link to the nonpharmacological Sleep Protocol that suggests offering a warm glass of milk or herbal tea, a 5-minute back rub, and relaxing music to patients (McDowell, Mion, Lydon, & Inouye, 1998). A “sleep kit” was provided on the unit with all of the items needed for the protocol. The nurses were also given pocket cards for sleep hygiene, the MMSE, and the CAM. Lastly, a positive CAM (suggesting presence of delirium) also triggered the nurse to notify the physician that the patient had possible delirium. All decision support content was based on the available evidence for the assessment, etiology, and management of delirium.

Figure 2.

Decision support screen for management and prevention of delirium.

Feasibility and usability of the screens were measured as the number of shifts with documentation divided by total number of patient shifts and by time in minutes between screen uses. If a nurse worked a 12-hour shift and documented at least once on the screens during this time, this was counted for both shifts using the time between minutes data for the screen use.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Between-group comparisons of patients who refused with those who agreed to participate were made using t tests for interval variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

RESULTS

During a 14-week period, 28 potentially eligible older adults were admitted to the study unit. No potentially eligible patients were missed for screening. Of those, 7 were excluded because they were verbally unresponsive and had an MMSE score of 0 (n = 4), a negative MBDRS score (n = 2), or acute stroke with aphasia (n = 1). Of the remaining 21 patients, 6 were eligible but refused to participate (29% refusal rate). Three patients and 3 family caregivers refused due to being too stressed and the family member’s concerns about not wanting to bother the patient. No participants dropped out. No statistical differences were found between eligible participants who refused and those who consented. The characteristics of the enrolled patients are displayed in the Table. The pilot study patients had a mean age of 83.4 (SD = 5.4 years), average hospital length of stay of 6.4 days (SD = 4.7), and a mean admission MMSE score of 14.8 (SD = 8.8).

TABLE.

EARLY NURSE DETECTION OF DELIRIUM SUPERIMPOSED ON DEMENTIA: PATIENT DATA

| MMSE | CAM | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Age | Gender | Length of Stay (days) | CDR | Admission | Discharge | Admission | Discharge |

| 1 | 81 | Male | 4 | 2 | 17 | 16 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 85 | Male | 15 | 0.5 | 20 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 88 | Male | 10 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 86 | Female | 2 | 3 | 25 | 26 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 82 | Male | 2 | 0.5 | 20 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 85 | Female | 13 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 90 | Female | 3 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | 95 | Male | 10 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| 9 | 72 | Male | 2 | 1 | 16 | 14 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 84 | Male | 10 | 0.5 | 27 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 82 | Male | 11 | 1 | 23 | 29 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 84 | Female | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 13 | 81 | Male | 2 | 0.5 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 79 | Female | 2 | 1 | 19 | 19 | 1 | 0 |

| 15 | 77 | Male | 3 | 1 | 16 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall mean (SD) | 83.4 (5.4) | 6.4 (4.7) | 1.4 (0.8) | 14.8 (8.8) | 15.2 (9.4) | |||

Note. CAM = Confusion Assessment Method, scored as no delirium (0), subsyndromal delirium (1), or full delirium (2); CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating scale, scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (no dementia) to 3 (severe dementia); MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination, scored from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive function.

Our second sample was composed of 55 unit-based RNs and 9 LPNs eligible to document on the EMR. Fifty-three percent of nurses attended the educational module. We did not collect demographic data from the nurse sample.

Nurse Adherence to EMR Documentation

There were 96 patient days consisting of 196 patient shifts. Fifty-five RNs documented on the assessment screens 196 times across 96 hospitalized days (100% adherence). Fortyfive RNs and 7 LPNs documented 147 times (75%) on the Sleep Protocol screen.

There were 96 patient days in the END DSD pilot data set. The average number of delirium assessments per day was 1.7. The assessments were evenly dispersed among the shifts: 57 entries on first shift (7:01 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.), 72 entries on second shift (3:01 p.m. to 11:00 p.m.), and 66 entries on third shift (11:01 p.m. to 7:00 a.m.). The screen for assessing the causes of the delirium pulled in entries from the nursing staff, such as medication (i.e., meperidine [Demerol®]), a positive urine culture, high noise levels, hearing impairment, and abnormal laboratory values (e.g., glucose). Some of the management strategies charted included avoiding daytime napping, mobilizing the patient, monitoring hydration status, simple communication, and scheduled toileting.

On the sleep section of the management screens, the average number of sleep entries per day was 1.32. More sleep screen entries were recorded on the evening (54) and night shifts (55). Examples of nurse comments during third shift were “no sedatives implemented” and “attempted to reduce noise during shift.” Examples of nurse comments on the evening shift were “attempted to keep patient from sleeping at 1900 [7:00 p.m.],” and “patient awake and visiting with family.” Thirty-eight sleep screen entries were recorded on the day shift. Comments charted included “patient is very lethargic since Seroquel® and Xanax given last night,” “we are trying to keep patient alert,” “patient drowsy, difficult to keep aroused,” and “patient kept up and active per protocol.”

Narrative Feedback about the Computer Screens

We solicited feedback from staff regarding the modules during and after the educational sessions and while they were actually using the screens. This was to increase adherence and enhance workload fit. We asked nurses which screens were most and least helpful as well as what alternative strategies were used, and solicited feedback regarding the relevance and their understanding of the modules as they actually used them. Nurses in all of the sessions requested additional cues and tools for assessing features of the CAM. These were incorporated into the assessment screen. None of the nurses indicated they had prior knowledge about assessing delirium in people with dementia. Two nurses indicated while using the screens in the study that combining and having fewer screens to access would be more user friendly.

Another common theme was concern about not medicating patients and having access to strategies such as the Sleep Protocol for the nursing management of delirium. One nurse stated, “The hardest part will be not medicating patients…. It is all we have.” Another noted, “It will be nice to have strategies besides calling psychiatry to medicate patients.” There were also comments that indicated some staff did not fully understand the recommendations related to trying to keep patients active while not overtiring them. For example, one nurse said, “Do we have to keep the patients up in the chair all day?” Staff also discussed the positive aspect of having a plan that would substitute for using psychoactive medication and suggested teaching the nurse aides to perform the nonpharmacological Sleep Protocol. Nurses also asked for other cognitive activities to stimulate patients during the daytime hours, stating that this would provide a management and prevention strategy they could delegate to nonlicensed staff. We added this to the screens based on the pilot study feedback (Figure 2).

Preliminary Efficacy of the Intervention

In this pilot study, the patients’ mean admission MMSE score was 14.8 (SD = 8.8). Ninety-three percent (14 of 15) of the patients either improved their MMSE scores by more than 3 points from admission to discharge or had no clinically significant change in their MMSE score (Table). One patient had a 2-point decrease in his MMSE score.

Patient and Family Satisfaction

Patients and families were both targeted for the satisfaction survey. Patients were asked if they enjoyed the intervention, but data were gathered from only 3 respondents, primarily due to RA inability to interview the patients before discharge. All of these 3 stated they enjoyed the intervention. When asked if they thought the intervention improved their mental status, 2 patients thought that it did; 1 patient said no. In regard to their physical status, 1 patient thought the intervention improved it, whereas 2 did not think so.

The results from the family satisfaction survey (n = 13) indicated 6 family members thought the patient strongly benefited from the intervention, 2 thought they did not, and 5 were uncertain about the benefit. Those who were uncertain were concerned that the patients’ dementia was too advanced. Only 8 family members responded to the question about whether they would recommend the intervention to others, and 7 of these said they would. The one family respondent who would not recommend the intervention said the family member was too confused to tell whether any benefit was realized from the intervention. This participant had an admission MMSE score of 1.

Family members were also able to provide narrative feedback about the study. One family member stated: “I think it was a good thing and I think she really enjoyed being part of it.” Some family members were not sure if their loved ones were able to realize the benefit because their dementia was more severe and stated: “My mother probably was too far along for this to be a lasting effect. Not sure about long-term benefits for her but think others would benefit a lot.”

DISCUSSION

Our most important finding was that we were able to enroll the majority of eligible patients and their family caregivers as a dyad without any attrition. Most of the patients’ MMSE scores improved or stayed the same from admission to discharge. These findings suggest a trend for patients in the intervention to improve their mental status scores, and both patients and family members were satisfied with and would recommend the intervention. We will test the efficacy of this intervention in a larger study.

The second major finding was the impact of the pilot study on nurses’ practice behavior. Only slightly more than half of the nurses attended the educational module. However, the nurses used the screens when they were prompted to do so. Overall, the nurses did not have problems using the assessment and management screens, and they seemed to prompt them to assess and manage delirium using current standards of care. Nurses did indicate they needed more education and perhaps handson assistance with understanding the assessment and management of delirium in their patients.

Similar studies have shown that decision support efforts enhance nurse recognition of patient phenomena (Miller, Scheinkestel, & Steele, 2009) and improve patient outcomes (Phansalkar, Weir, Morris, & Warner, 2008). Decision support tools that integrate patient information, similar to our design, have been shown to enhance diagnostic agreement, whereas designs that divide information reduce agreement (Miller et al., 2009). This is an important feature when the targeted phenomenon is a complicated syndrome such as DSD.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

We did learn some lessons for our future study. More emphasis needs to be placed on preparing the nurses for the intervention and providing ongoing support for using the computerized decision support screens. One large multicenter study of implementing computerized protocols showed that although nurses believed their new computerized decision support system improved quality, barriers to their acceptance included ease of data entry, failure to integrate the algorithm into their existing workflow, and the degree of involvement of the nurses in the transition (Phansalkar et al., 2008). We plan to address this last issue in our larger study with the use of unitbased champions and regular feedback to the nursing staff. One of our study nurses also indicated that having fewer screens to scroll through would make it easier to navigate, and one nurse thought the assessment of causes and management screens could be combined to reduce nurse burden.

A recent study found that nurses’ attitudes toward implementation were affected by their level of knowledge about the content of the protocols, the quality and accuracy of the content, and ultimately, the trust they had in whether use of the protocols would enhance their ability to care for their patients (Phansalkar et al., 2008). Similar findings were reported by researchers when implementing computerized decision support for telehealth nurses in Sweden (Ernesäter, Holmström, & Engström, 2009). When nurses had confidence in the content of the protocols, they described an enhanced level of professional confidence, as well as a decreased feeling of risk for making decisions in error.

STUDY STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This pilot study has several important limitations. Most important, it did not have a randomized control group, although clinical effectiveness was not the goal of the study. In addition, this study is a pilot and does not address long-term adherence to the computerized support over time. In addition, the protocol was not tested in its entirety. Finally, we had less than optimal attendance at the educational sessions. Approximately half of the RNs documenting on the screens were at the educational sessions describing the screens; however, unit nurses were also given an overview by the RA when a participant was enrolled in the study. All nurses received some orientation to the screens. This will also be addressed in our larger study with an online module as a booster session, by providing incentives for all nurses on the unit to complete the educational sessions, and with regular feedback and rounds with nursing staff.

Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths and is one of the first to test the use of the CAM in the EMR. These adherence statistics and patient data demonstrate that, with reinforcement, we will have adequate adherence rates to implement this intervention successfully in a larger trial. Further, this pilot study provided experience in the participant enrollment procedures and “live” testing of the computer screens, and gave us feedback and satisfaction data to refine future studies. Although this pilot study did not measure long-term adherence, we will be able to test this more fully in the future.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Delirium (acute confusion) is common and costly in people with dementia, resulting in longer hospital stays, more complications, greater functional decline, and death. This research tested the practicality of using the EMR and education to improve detection and management of delirium and found that nurses were able to use the assessment and management screens without increased burden and that patients and families were satisfied with the intervention. A delirium screening tool integrated into the EMR is feasible for nurses to use. A larger study is needed to test whether it actually improves nurse detection of delirium and patient outcomes such as delirium severity.

Caring for patients with delirium is very nursing care intensive, thus testing methods that facilitate the care of these patients is important. Randomized trials using information technology and feedback with nurses to improve care of vulnerable older adults with delirium in community hospitals are desperately needed. This pilot study and future larger studies will build the support and evidence needed to replicate this approach in other settings.

CONCLUSION

The success of this pilot study may forecast the adoption of future decision support efforts, as well as improved outcomes for hospitalized older adults with DSD. Despite the fact that delirium in people with dementia is common, deadly, and costly, there are currently no published reports of the use of the EMR in delirium detection and management. Interventions tailored specifically to people with dementia, in whom delirium is so common and difficult to prevent, are integral to efforts to prevent delirium in and improve quality of care for older adults. The success of this effort may encourage use of similar information technology in other settings such as the home and long-term care.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (grant R03 AG023216-01A2) and the National Institute of Nursing Research (grant 1 R01 NR011042-01A1). This study was presented in part at the 62nd annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America.

The authors thank the older adults, nurses, research assistants, and hospital staff for making this study possible.

Footnotes

The authors disclose that they have no significant financial interests in any product or class of products discussed directly or indirectly in this activity.

Contributor Information

Donna M. Fick, Pennsylvania State University School of Nursing, University Park.

Melinda R. Steis, National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Nursing, NewCourtland Center for Transitions and Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Lorraine C. Mion, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville, Tennessee.

Joyce L. Walls, Information Services, Mount Nittany Medical Center, State College, Pennsylvania.

References

- Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1968;114:797–811. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.512.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, Donelan K, Ferris TG, Jha A, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care—A national survey of physicians. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:50–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernesäter A, Holmström I, Engström M. Telenurses’ experiences of working with computerized decision support: Supporting, inhibiting and quality improving. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65:1074–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.04966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick D, Foreman M. Consequences of not recognizing delirium superimposed on dementia in hospitalized elderly individuals. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2000;26(1):30–40. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20000101-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick D, Kolanowski A, Waller J. High prevalence of central nervous system medications in community-dwelling older adults with dementia over a three-year period. Aging & Mental Health. 2007;11:588–595. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:1723–1732. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick DM, Kolanowski AM, Waller JL, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia in a community-dwelling managed care population: A 3-year retrospective study of occurrence, costs, and utilization. Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2005;60:748–753. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick DM, Mion LC. Delirium superimposed on dementia. American Journal of Nursing. 2008;108(1):52–60. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000304476.80530.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK. Delirium in hospitalized elderly patients: Recognition, evaluation, and management. Connecticut Medicine. 1993;57:309–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:1157–1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: The Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detection of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;113:941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168:27–32. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JA, Mion LC, Lydon TJ, Inouye SK. A nonpharmacologic sleep protocol for hospitalized older patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46:700–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Scheinkestel C, Steele C. The effects of clinical information presentation on physicians’ and nurses’ decision-making in ICUs. Applied Ergonomics. 2009;40:753–761. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman AD, Clarke MJ, Stewart LA. From science to practice. Meta-analyses using individual patient data are needed. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274:845–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.10.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phansalkar S, Weir CR, Morris AH, Warner HR. Clinicians’ perceptions about use of computerized protocols: A multicenter study. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2008;77:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The Mini-Mental State Examination: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyer P, Richard S, Doucet L, Carmichael PH. Predisposing factors associated with delirium among demented long-term care residents. Clinical Nursing Research. 2009;18:153–171. doi: 10.1177/1054773809333434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]