Abstract

Many assays to evaluate the nature, breadth, and quality of antigen-specific T cell responses are currently applied in human medicine. In most cases, assay-related protocols are developed on an individual laboratory basis, resulting in a large number of different protocols being applied worldwide. Together with the inherent complexity of cellular assays, this leads to unnecessary limitations in the ability to compare results generated across institutions. Over the past few years a number of critical assay parameters have been identified which influence test performance irrespective of protocol, material, and reagents used. Describing these critical factors as an integral part of any published report will both facilitate the comparison of data generated across institutions and lead to improvements in the assays themselves. To this end, the Minimal Information About T Cell Assays (MIATA) project was initiated. The objective of MIATA is to achieve a broad consensus on which T cell assay parameters should be reported in scientific publications and to propose a mechanism for reporting these in a systematic manner. To add maximum value for the scientific community, a step-wise, open, and field-spanning approach has been taken to achieve technical precision, user-friendliness, adequate incorporation of concerns, and high acceptance among peers. Here, we describe the past, present, and future perspectives of the MIATA project. We suggest that the approach taken can be generically applied to projects in which a broad consensus has to be reached among scientists working in fragmented fields, such as immunology. An additional objective of this undertaking is to engage the broader scientific community to comment on MIATA and to become an active participant in the project.

Keywords: Minimal information about T cell assays, Reporting guidelines, Immune monitoring, MIATA

Introduction

For many years, the development of active immunotherapy to treat cancer was considered a pursuit with uncertain outcome that was met by increasing skepticism, in part resulting from failure to demonstrate clinical efficacy [1, 2]. Recent reports of success from randomized phase III trials [3–5] and the first approval for a therapeutic vaccine [6] now set the stage for a new era of immunotherapy with greater availability of biological samples from large controlled clinical trials on the horizon. A crucial role for T cell responses in active immunotherapy has been demonstrated in numerous animal models as well as in clinical trials [7, 8]. A large number of different assays for measuring T cell quality and function has been developed and applied in such clinical trials. The identification, development, and eventual validation of T cell biomarkers that correlate with product bioactivity and clinical response is a challenging and complex process, but is required for understanding and improving on response rates. This necessitates an integrated clinical development plan, a systematic and comprehensive standardized scheme for sample procurement/processing, and biomarker assays including data analysis to be applied. To this end, quality-enabling laboratory infrastructure needs to be established, which is essential for large and well-conducted trials, culminating in the enhanced potential to measure successful induction of clinical responses [9, 10]. Because the technical validation of assays for measuring cellular immune biomarkers is not trivial, systematic mono- and multi-center efforts have been initiated in the different fields of cancer immunology, autoimmunity and infectious diseases to harmonize and standardize T cell assays. These systematic efforts have led to the identification of critical factors that influence assay performance and the consequent formulation of guidelines to improve and harmonize T cell assays across laboratories [11–16]. These harmonization efforts increased the awareness to the problem that, despite the vast body of literature describing results from T cell assays, the majority of scientific publications lack important information on crucial steps in the assay process, precluding a full understanding and accurate interpretation of published data sets and limiting the ability to reproduce results and compare data sets between centers or perform meta-analysis. Undoubtedly, having a more uniform and complete reporting structure would not only serve the broad interests of the scientific community, but would also be beneficial in enhancing the accurate communication of methodologies between immunotherapy programs.

In 2008, a core team of immunologists from Europe and the United States embarked on the establishment of a Minimal Information (MI) project for T cell assays and set the stage for an ongoing large-scale, field-spanning effort to generate a widely acceptable reporting framework to support scientific publications and enhance the utility of presented data. The project on Minimal Information About T Cell Assays (MIATA) was announced in October 2009 [17]; and a dedicated web site was launched in parallel with the listing of a first draft of guidelines, consisting of five modules based on the gained knowledge from harmonization efforts about factors that critically influence assay results, namely the requirement to provide information on the (1) sample, (2) the assay, (3) data acquisition, (4) the interpretation of data as well as (5) the lab environment [18]. At the same time, a public consultation phase was initiated. Since then, based primarily on the input from the public consultation process and public workshops, the MIATA project has undergone a process of evolution and maturation, resulting in a streamlined set of guidelines for reporting on T cell assays. These guidelines can be found on the MIATA website (http://www.miataproject.org). Here, we elaborate on the ongoing collaborative approach taken to develop MIATA guidelines, which was found to be essential in order to achieve the desired high degree of quality and acceptability for T cell assays. The process also led to the identification of critical factors for success that might be applicable to similar projects in other areas of science.

Minimal information projects

The concept of Minimal Information projects was pioneered by Brazma et al. [19], for complex analytical assays that generate large data sets with several layers of information, to meet demands in the area of microarrays. Subsequently, the first successful MI project addressing microarray experiments was introduced [20]. Meanwhile over 30 MI projects for different types of assays have been proposed, many of which are listed under the MIBBI portal, which provides assistance to investigators in identifying suitable MI guidelines for their work [21]. Most MI projects are (1) primarily designed for high-throughput assays and (2) require detailed annotation of samples and related data sets to populate large databases and allow for data mining by third parties. The majority of current T cell assays do not fall under the category “high throughput”, and current data sharing refers mainly to comparing results from different groups working in similar areas, rather than exploring existing data sets generated by third parties. The introduction of new technologies in the immune assay field might change this situation [22, 23], and applicable MI projects including MIATA need to be adaptable and expandable for data mining, for example in an envisioned Human Immunity Project [24]. It should be noted that a minimal information framework for publications might significantly differ from a framework for populating large databases including content and syntax [25].

What is MIATA?

MIATA is a framework for WHAT and HOW to report when publishing immune monitoring tests and results. The overall goal for MIATA is to provide the reader with the minimal information necessary to understand how reported data related to T cell assays were generated [26]. This is accomplished by providing a structured basis for reporting the information that allows the full and objective evaluation of the presented data sets, as well as for the ability to integrate data sets across studies. MIATA focuses solely on the reporting content and structure for assays, not the assay content and structure.

What MIATA is not

MIATA is not an effort to impose specific standards on how T cell assays are performed, including assay standardization, validation, and setup of the appropriate laboratory environment. MIATA is without prejudice on how and when immune monitoring is performed. These issues need to be addressed by the individual investigators before a study is initiated. Consequently, conformity to the MIATA guidelines does not require the use of standardized assay protocols or a certain laboratory setup. Freedom of research and flexibility in the choice of assays and reagents used are of utmost importance and must not be limited at any time by any MI project.

Minimal information projects with overlap

Several MI projects with some degree of overlap with MIATA exist, for example Minimal Information About a Cellular Assay (MIACA) [27], Minimum Information for a Flow Cytometry Experiment (MIFlowCyt) [28], the Publication on Publishing Flow Cytometry Data [29] and Reporting recommendations for tumor Marker prognostic studies (REMARK) [30]. Each of these projects is unique, and all are based on the expertise and input of highly experienced investigators. The REMARK criteria from the Statistics Subcommittee of the NCI-EORTC Working Group on Cancer Diagnostics have achieved a notable level of awareness in the community, supported by parallel publications in and endorsement by several international journals. Although REMARK has proven its value in several prognostic biomarker study publications [31], it does not specifically address aspects unique to T cell assays. Further, publications that claim conformity to other MI projects with overlap to MIATA are sparse at most. This might be partially due to the overwhelming amount of information required by other MI projects that were designed primarily to support data mining. These circumstances provide the foundations for the two-step approach introduced here with the initial focus on scientific publications, and later expandability for data mining. Such a process has the potential for wide acceptance and a successful adoption rate of MIATA, as it could for other MI projects.

Factors for success

Several major challenges exist for activities that aim to impact current practices and achieve broad consensus among scientists who work in fragmented fields of science (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors of success

| Factors of success for MI projects |

|---|

| Technically precise (captures all essential information of the assay) |

| User-friendly (truly minimal and clearly understandable) |

| No existing concerns to prevent conforming |

| Accepted by peers |

| Added value to user/community |

To begin, implementation of a new process (e.g., structured framework to report data from analytical assays such as MIATA) in a lab environment is time-consuming. It requires investigators to read, understand and approve the new framework internally, to teach staff members to apply the new process correctly, and to ensure proper execution. Consequently, any new reporting framework proposed to the field has to find a balance between being easy to understand and implement and requesting an amount of information sufficient to fulfill its purpose. Clearly, MI projects should be as “minimal” as possible. However, while minimizing the content of a reporting framework beyond a certain degree might make it easier to implement, it can also decrease its value significantly. Achieving the appropriate balance between not asking for too much or too little information has been and still is one of the most difficult tasks in the evolution of the MIATA project and is the focus of many discussions among the investigators involved. Clearly, the additional workload associated with implementation of MIATA should never outweigh its added value for individual investigators and the scientific community.

Even a user-friendly and technically precise reporting framework will not be of any value unless broadly accepted and adopted by scientists and journals. An investigator’s decision to accept or reject a proposed reporting framework will critically depend on the absence or existence of any concerns related to conforming to the guidelines. Various concerns were also raised after the first draft of MIATA (version 0) was published. It became clear that specific concerns were typically shared by groups of colleagues with a similar focus of their work (e.g., assay validation, research labs, labs performing correlative studies in larger clinical trials, applicants for funding schemes). Part of the MIATA approach has been to carefully consider and address each of these concerns en route to establishing a final set of reporting guidelines.

Finally, the adoption of MIATA will crucially depend on knowledge of the framework and its acceptance as standard practice by peers and stakeholders in the field. Despite the overwhelming redundancy in the nature of the assays used to evaluate immune responses across specialized fields such as cancer immunology, autoimmunity, transplantation, and infectious diseases, scientists in each of those fields have historically tended to operate as more or less isolated groups, developing closely related assays in a parallel, often redundant, fragmented, and non-integrated manner. Geographic fragmentation, facilitated by the establishment of specialty societies in the USA, Europe, parts of Asia, and Australia has further added to the non-integrated nature of T cell assay development. This fragmentation clearly needs to be addressed and overcome by integrating the expertise from as many directly involved peers as possible into the framework, independent of location, affiliation or background.

The past, presence, and future of MIATA

Many MI projects are authored by a significant number of scientists, and the process of reaching a consensus through discussions and seminars is a hallmark of most, if not all of them. On closer examination, the consensus-building process commonly appears to be confined to a group of experts, and it is not always clear at what level peers were involved.

The vision of the MIATA core team was to reach out to as many colleagues as possible in different areas of immunology and in laboratories involved in research and clinical trial monitoring. We believe that contributors to the process should include the scientists performing the assay, as well as principal investigators, regulatory authorities, and journal editors. Since its initial phase, the MIATA project has been working towards integrating suggestions and criticism from experts representing different areas of immunology, and from societies across geographic boundaries; accordingly, primary authors on this manuscript are active participants and members of a wide range of immunology associations. MIATA never was or shall be a closed community excluding individual colleagues or groups. On the contrary, the core team is pursuing a bottom-up approach and is reaching out to an increasing number of colleagues to integrate expertise into the framework from as many directly involved peers as possible and thereby make them an integral and important part of the MIATA project.

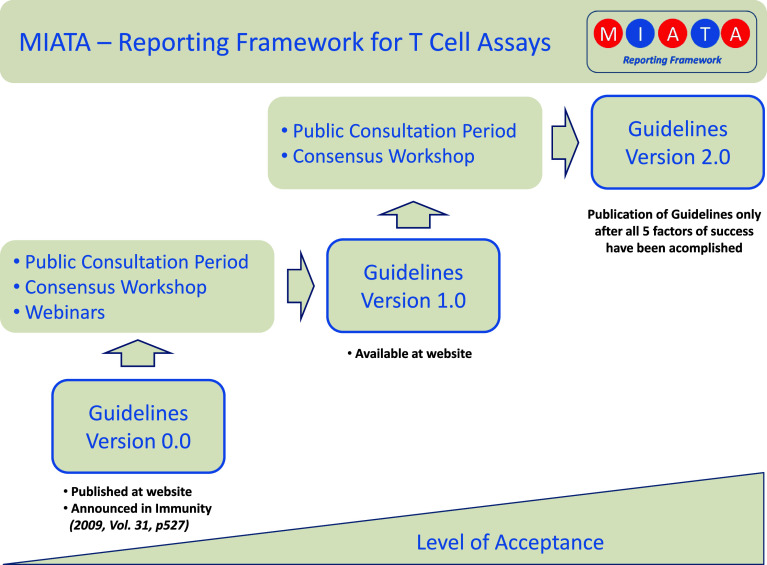

Transparency at every level and step, open access to any communication and ongoing discussion, and flexibility during the maturation process were key process features for MIATA from the beginning. Important components of the MIATA maturation process are (Fig. 1).

An independent project web site (http://www.miataproject.org)

An expanding network of supporting organizations

A public consultation period on the initial guideline draft (Version 0)

A public workshop and follow-up webinars

A public consultation period on the updated guidelines (Version 1)

A concluding workshop to consolidate the publication framework.

Fig. 1.

Pathway for achieving high quality and acceptance among peers. A step-wise and open process was initiated for MIATA. A dedicated independent website was launched and public consultation periods, workshops, and webinars are being conducted to achieve technical precision, user-friendliness, adequate incorporation of concerns, high acceptance rates among peers, an ultimately maximum value for the scientific community

The project-related web site was found to be an invaluable tool for the transparent recording of MIATA’s progress. It proved to be an efficient tool for the ongoing consultation period during which each comment and responses to those comments were posted. The web site itself is run independently of any organization or other web site.

Public consultation period, workshop, and webinars

An important factor for the advancement of the MIATA process was the support and patronage received early on by organizations, namely the Cancer Immunotherapy Consortium of the Cancer Research Institute (CIC/CRI) and the Association of Cancer Immunotherapy (CIMT), the Human Immune Monitoring Center at Stanford, and the Italian Network for Biotherapy of Cancer (NIBIT). During the public consultation period, investigators active in the field were asked to comment on the initial draft of the MIATA guidelines. Within 5 months, 54 comments were posted from over 80 contributors from 14 countries, from diverse fields and backgrounds. The comments received were constructive and supportive, and could be divided into two main categories:

comments on the MIATA modules focusing on the specific content of each module and sub-module; and

comments on the overall focus and intent of MIATA, including logistics for its feasibility and applicability.

All comments were reviewed and considered in light of the module, sub-module, and general topic addressed, and the overall messages distilled and summarized in a discussion document for the first workshop held during the annual CIC/CRI meeting in Washington DC in March 2010. For this public workshop, expert panelists from different immunology fields (cancer, infectious diseases, autoimmunity), regulatory agencies, and journal editors were invited to discuss the initial guideline draft and comments received, and to update MIATA to version 1.

It became clear that general questions had to be addressed and consensus had to be reached first, before the specific content could be tackled. Specifically, the following topics were intensely discussed during the workshop:

Scope of MIATA (framework for scientific publications vs. annotations for data base efforts)

Focused application for the MIATA publication framework (human immune monitoring versus T cell immune assays in general)

Striking a balance between minimal and sufficient information

The importance of freedom of research.

In effect, the focus of MIATA was re-defined and specified as a reporting framework for scientific publications of human immune monitoring results. After its successful implementation for the described purpose, MIATA should be adaptable in a step-wise manner to support annotations of immune monitoring data sets, for example in the context of a Human Immunity Project [24]. It needs to be stressed that the consensus reached on these topics was found to be of the utmost importance for the increasing acceptance and continuation of MIATA.

Subsequently, the specific content of the guidelines was discussed by reviewing each single sub-module and related comments received. Due to the volume of information and impressive amount of feedback obtained, this process was extended over the remaining workshop and three separate webinars. A consensus was reached on the basis of professional discussions among panelists, and in consequence the MIATA guidelines were upgraded to Version 1 [18], parts of which differ considerably from the original draft.

Next steps and future perspectives

As for the initial guidelines, the updated MIATA modules have been posted on the project’s web site, and the field is once again invited to review and comment on its content. The first feedback already received indicates increasing agreement with the current framework. Most of the proposed changes and additions focus on single sub-modules.

In addition to soliciting further comments on the MIATA Version 1 guidelines, the current focus of the core team is to increase general awareness of the project in the field. In parallel, efforts are underway to promote the adoption of MIATA by scientists and journals. The MIATA experience has demonstrated that surprisingly little knowledge exists among immunologists about Minimal Information concepts and existing projects. Several recent articles addressing publication guidelines for optimized multicolor immunofluorescence panels might aid in raising further awareness [32]. Keeping the high value of these projects in mind, it is important to disseminate information about them and at the same time initiate collaborations among all stakeholders and MI projects that overlap in any way with MIATA. This will help to avoid duplication of effort or even competition, while offering guidance to the community in their choice of the most suitable assays and implementation of the appropriate frameworks in their scientific work.

The current MIATA Version 1 is the result of a highly collaborative effort. It is essential for the success of this project to promote the further input of the community and to enhance the discussion and final consensus between scientists and scientific journals.

Acknowledgments

Funding for open access publication of this manuscript was provided by the Cancer Immunotherapy Consortium of the Cancer Research Institute (CIC/CRI) and the Cancer Immunotherapy Immunoguiding Program (CIP/CIMT), both being nonprofit organizations. They also offered generous support and patronage for the first MIATA workshop in Washington in March 2010. C.M.B and S.H.v.d.B were supported by the Wallace Coulter Foundation (Florida, USA) which also supported the organization of the MIATA workshop. The authors are indebted to all colleagues that contributed to the generation of the current version of MIATA at any stage of the project.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix: Many authors of this article also contributed directly with posted comments and panel participation, but are not listed here again

James Allison, MSKCC, New York, NY, USA

Sofija Andjelic, Regeneron, Inc., Tarrytown, NY, USA

Victor Appay, Université Pierre et Marie Curie-Paris, France

Sebastian Attig, Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, Germany

Christine Bain, Transgene SA, Illkirch Graffenstaden, France

Maries van den Broek, University Hospital Zürich, Switzerland

Lisa Butterfield, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, PA, USA

Jonathan Cebon, LICR Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia

Vincenzo Cerundolo, University of Oxford, UK

Weisan Chen, LICR Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia

Josephine Cox, IAVI, Rockville, MD, USA

Tina Dalgaard, Aarhus University, Tjele, Denmark

Ian Davis, LICR Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia

Guido Ferrari, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Sacha Gnjatic, LICR, MSKCC, New York, NY, USA

Peter Gottlieb, University of Colorado, USA

Cecile Gouttefangeas, University of Tübingen, Germany

Philip Greenberg, University of Washington, Seattle, USA

Stefanie Groß, Unversity of Erlangen, Germany

James Gulley, NCI, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Leif Håkansson, University Hospital Linkoeping, Sweden

Sine Hardrup, University Hospital Herlev, Denmark

Zaima Mazorra Herrera, Center of Molecular Immunology, Havana, Cuba

John Hural, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA

Simone A. Joosten, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands

Eckhard Kämpgen, University of Erlangen, Germany

Florian Kern, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

Samir Khleif, NCI, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Alexander Knuth, University Hospital Zürich, Switzerland

Tania Køllgaard, University Hospital Herlev, Denmark

Sebastian Kreiter, Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, Germany

Jim Lane, VRC/NIAID, Bethesda, MD, USA

Paul V. Lehmann, Cellular Technology Ltd., Shaker Heights, OH, USA

Uri Lopatin, Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA

Markus Mäurer, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

Michele Maio, University Hospital of Siena, Italy

Anatoli Malyguine, SAIC-Frederick, Inc. NCI-Frederick, MD, USA

Ann Mander, Southampton University Hospitals, Southampton, UK

Francesco M Marincola, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

Cristina Musselli, Antigenics, Lexington, MA, USA

Marcelo Navarrete, Universitätsklinikum Freiburg, Germany

Hugues JM Nicolay, University Hospital of Siena, Italy

Julie Nielsen, BC Cancer Agency, Victoria, BC, Canada

Hiroyoshi Nishikawa, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, Japan

Pamela Norberg, Alphavax, Inc., RTP, NC, USA

Tom H. M. Ottenhoff, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands

Christian Ottensmeier, Southampton University Hospitals, UK

Joanne Parker, ViraCor IBT-Laboratories, Lenexa, KS, USA

Anne Plant, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA

Fiona Powell, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

Hans-Georg Rammensee, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Elizabeth Reap, Alphavax, Inc., RTP, NC, USA

Licia Rivoltini, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Milano, Italy

Mario Roederer, VRC, NIH, USA

Ronald Rooke, Transgene SA, Illkirch Graffenstaden, France

Ugur Sahin, Johannes Gutenberg-University, Mainz, Germany

Regina Samorski, Immatics, Tübingen, Germany

Darien Toledo Santamaría, Center of Molecular Immunology, Havana, Cuba

Marcella Sarzotti-Kelsoe, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA

Dolores Schendel, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Germany

Marij JP Schoenmaekers-Welters, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands

Gerold Schuler, University of Erlangen, Germany

Kimberly Shafer-Weaver SAIC-Frederick, Inc. NCI-Frederick, MD USA

Padmanee Sharma, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

Janet Siebert, Cytoanalytics, Denver, CO, USA

Craig Slingluff, University of Virginia, USA

Patricia D’Souza, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Daniel Speiser, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Lausanne Branch University Hospital (CHUV), Switzerland

Per Thor Straten, University Hospital Herlev, Denmark

Chris Taylor, The European Bioinformatics Institute, UK

Arthur A. Vandenbark, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA

Steffen Walter, Immatics, Tübingen, Germany

Dominic Warrino, ViraCor IBT-Laboratories, Lenexa, KS, USA

Aubrey Watson, Alphavax, Inc., RTP, NC, USA

Jeffrey Weber, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA

Jedd Wolchok, MSKCC, New York, NY, USA

Cassian Yee, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, USA

Jianda Yuan, MSKCC, New York, NY, USA

Laurence Zitvogel, Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France

Heinz Zwierzina, Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria.

Footnotes

C. M. Britten and S. Janetzki contributed equally.

For the MIATA panelists and contributors. Alphabetical listing of MIATA contributors and panelists are given in Appendix.

References

- 1.Goldman B, DeFrancesco L. The cancer vaccine roller coaster. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(2):129–139. doi: 10.1038/nbt0209-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finke LH, Wentworth K, Blumenstein B, Rudolph NS, Levitsky H, Hoos A. Lessons from randomized phase III studies with active cancer immunotherapies—outcomes from the 2006 meeting of the Cancer Vaccine Consortium (CVC) Vaccine. 2007;25(Suppl 2):B97–B109. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster SJ, Neelapu SS, Gause BL, Muggia FM, Gockerman JP, Sotomayor EM, Winter JN, Flowers CR, Stergiou AM, Kwak LW, For the BiovaxID Phase III Study Investigators Idiotype vaccine therapy (biovaxid) in follicular lymphoma in first complete remission: phase III clinical trial results. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl; Abstr 2):18s. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson D, Richards J, Conry RM, Miller D, Triesman J, Gailani F, Riley LB, Vena D, Hwu P. A phase III multi-institutional randomized study of immunization with the gp100: 209–217 (210 m) peptide followed by high-dose IL-2 compared with high-dose IL-2 alone in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:18s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB et al (2010) Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, Redfern CH, Ferrari AC, Dreicer R, Sims RB, Xu Y, Frohlich MW, Schellhammer PF. Sipuleucel-t immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkwood JM, Lee S, Moschos SJ, Albertini MR, Michalak JC, Sander C, Whiteside T, Butterfield LH, Weiner L. Immunogenicity and antitumor effects of vaccination with peptide vaccine +/− granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor and/or IFN-alpha2b in advanced metastatic melanoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Phase II Trial E1696. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(4):1443–1451. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, Vloon AP, et al. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(19):1838–1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roep BO, Peakman M. Surrogate end points in the design of immunotherapy trials: emerging lessons from type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(2):145–152. doi: 10.1038/nri2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalos M. An integrative paradigm to impart quality to correlative science. J Transl Med. 2010;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schloot NC, Meierhoff G, Karlsson Faresjo M, Ott P, Putnam A, Lehmann P, Gottlieb P, Roep BO, Peakman M, Tree T. Comparison of cytokine elispot assay formats for the detection of islet antigen autoreactive t cells. Report of the third immunology of diabetes society t-cell workshop. J Autoimmun. 2003;21(4):365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janetzki S, Panageas KS, Ben-Porat L, Boyer J, Britten CM, Clay TM, Kalos M, Maecker HT, Romero P, Yuan J, Kast WM, Hoos A. Results and harmonization guidelines from two large-scale international Elispot proficiency panels conducted by the Cancer Vaccine Consortium (CVC/SVI) Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(3):303–315. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0380-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Britten CM, Janetzki S, Ben-Porat L, Clay TM, Kalos M, Maecker H, Odunsi K, Pride M, Old L, Hoos A, Romero P. Harmonization guidelines for HLA-peptide multimer assays derived from results of a large scale international proficiency panel of the Cancer Vaccine Consortium. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(10):1701–1713. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0681-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanekom WA, Dockrell HM, Ottenhoff TH, Doherty TM, Fletcher H, McShane H, Weichold FF, Hoft DF, Parida SK, Fruth UJ. Immunological outcomes of new tuberculosis vaccine trials: WHO panel recommendations. PLoS Med. 2008;5(7):e145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith SG, Joosten SA, Verscheure V, Pathan AA, McShane H, Ottenhoff TH, Dockrell HM, Mascart F. Identification of major factors influencing ELISpot-based monitoring of cellular responses to antigens from Mycobacterium tuberculosis . PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Britten CM, Gouttefangeas C, Welters MJ, Pawelec G, Koch S, Ottensmeier C, et al. The CIMT-monitoring panel: a two-step approach to harmonize the enumeration of antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes by structural and functional assays. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(3):289–302. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0378-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janetzki S, Britten CM, Kalos M, Levitsky HI, Maecker HT, Melief CJM, Old LJ, Romero P, Hoos A, Davis MM. “MIATA”-minimal information about T cell assays. Immunity. 2009;31(19833080):527–528. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The MIATA project (2010)http://miataproject.org/. Accessed September 24

- 19.Brazma A, Robinson A, Cameron G, Ashburner M. One-stop shop for microarray data. Nature. 2000;403(6771):699–700. doi: 10.1038/35001676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brazma A, Hingamp P, Quackenbush J, Sherlock G, Spellman P, Stoeckert C, et al. Minimum information about a microarray experiment (miame)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat Genet. 2001;29(4):365–371. doi: 10.1038/ng1201-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor CF, Field D, Sansone S-A, Aerts J, Apweiler R, Ashburner M, et al. Promoting coherent minimum reporting guidelines for biological and biomedical investigations: the MIBBI project. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(18688244):889–896. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maecker HT, Nolan GP, Fathman CG. New technologies for autoimmune disease monitoring. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17(4):322–328. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32833ada91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ornatsky O, Bandura D, Baranov V, Nitz M, Winnik MA, Tanner S (2010) Highly multiparametric analysis by mass cytometry. J Immunol Methods. doi:10.1016/j.jim.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Davis MM. A prescription for human immunology. Immunity. 2008;29(6):835–838. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgoon LD. Clearing the standards landscape: the semantics of terminology and their impact on toxicogenomics. Toxicol Sci. 2007;99(2):403–412. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orchard S, Taylor CF. Debunking minimum information myths: one hat need not fit all. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;25(4):171–172. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MIACA (minimum information about a cellular assay) (2010) http://sourceforge.net/projects/miaca/. Accessed September 24

- 28.Lee JA, Spidlen J, Boyce K, Cai J, Crosbie N, Dalphin M, et al. Miflowcyt: the minimum information about a flow cytometry experiment. Cytometry A. 2008;73(10):926–930. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarez DF, Helm K, Degregori J, Roederer M, Majka SM (2009) Publishing flow cytometry data. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00313.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (remark) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(16):1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mallett S, Timmer A, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG. Reporting of prognostic studies of tumour markers: a review of published articles in relation to remark guidelines. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(1):173–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahnke Y, Chattopadhyay P, Roederer M. Publication of optimized multicolor immunofluorescence panels. Cytometry A. 2010;77(9):814–818. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]