Abstract

Reactivation of Hedgehog (Hh), a morphogenic signaling pathway that controls progenitor cell fate and tissue construction during embryogenesis occurs during many types of liver injury in adult. The net effects of activating the Hedgehog pathway include expansion of liver progenitor populations to promote liver regeneration, but also hepatic accumulation of inflammatory cells, liver fibrogenesis, and vascular remodeling. All of these latter responses are known to be involved in the pathogenesis of cirrhosis. In addition, Hh signaling may play a role in primary liver cancers, such as cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Study of Hedgehog signaling in liver cells is in its infancy. Additional research in this area is justified given growing experimental and clinical data supporting a role for the pathway in regulating outcomes of liver injury.

General Significance of the Hedgehog Pathway

Hedgehog (Hh) is a signaling pathways that regulates critical cell fate decisions, including proliferation, apoptosis, migration and differentiation. The pathway plays vital roles in tissue morphogenesis during fetal development. It also modulates wound healing responses in a number of adult tissues, including the liver [24, 84]. The key events involved in Hh signaling are depicted in Fig 1. Hh signaling is initiated by a family of ligands (Sonic hedgehog - Shh, Indian hedgehog -Ihh, and Desert hedgehog- Dhh) which interact with a cell surface receptor (Patched - Ptc) that is expressed on Hh responsive target cells. This interaction de-represses activity of another molecule, Smoothened (Smo), and permits the propagation of intracellular signals that culminate in the nuclear localization of Glioblastoma (Gli) family transcription factors (Gli1, Gli2, Gli3) that regulate the expression of Gli-target genes (Fig 1a–b). Pertinent details about the Hh signaling pathway are summarized in the next section in order to highlight the general implications of pathway activation, as well as the inherent complexity of its regulation. The remainder of the review focuses on the role of Hh signaling in adult liver repair.

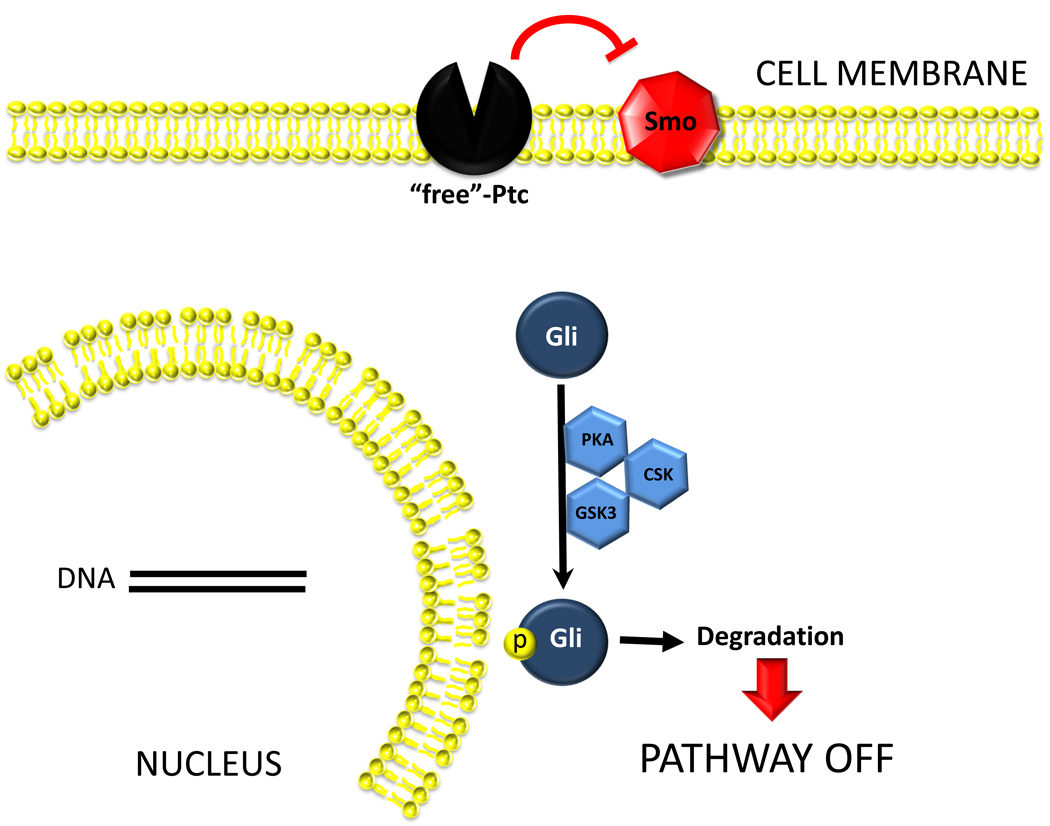

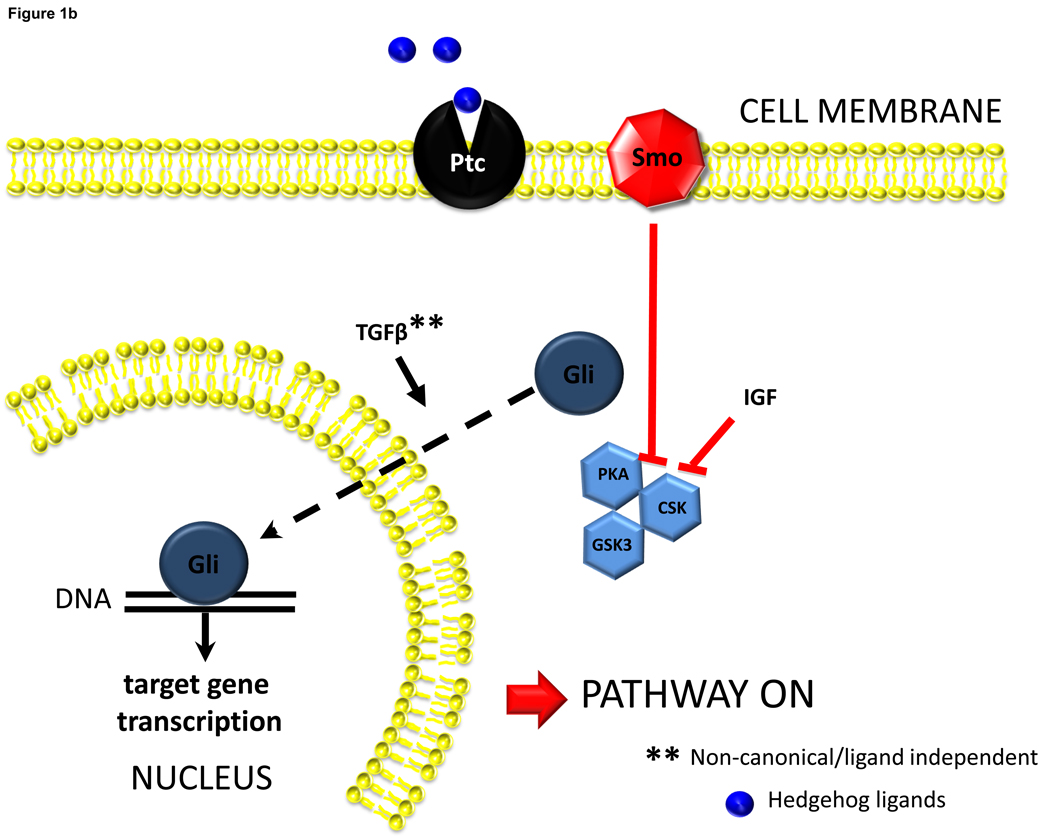

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Hh pathway is silent in Hh-responsive cells when Hh ligands are absent. Cells that are capable of responding to Hh ligands (i.e., Hh-responsive cells) express Hh receptors. Patched (Ptc) is the receptor that physically interacts with Hh ligands. In the absence of Hh ligands, Ptc represses the activation of a co-receptor-like molecule, Smoothened (Smo). This repression prevents Smo from interacting with other intracellular factors that permit the stabilization and accumulation of Glioblastoma (Gli) transcription factors. Thus, Gli proteins undergo phosphorylation by various intracellular kinases (PKA, GSK3b, CSK), become ubiquitinated, move to proteasomes and are degraded. Reduced availability of Gli factors influences the transcription of their target genes. Lack of Gli1 and Gli2 generally reduces target gene transcription, while lack of Gli3 can either stimulate or inhibit transcriptional activity.

Figure 1b. Hh ligands activate Hh pathway signaling. Interaction between Hh ligands and Ptc liberates Smoothened from the normal repressive actions of Ptc. This results in eventual inhibition of factors the promote Gli phosphorylation/degradation, and permits cellular accumulation of Gli. Other factors that inhibit Gli-phosphorylation, such as insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF), have also been shown to facilitate stabilization of Gli1 in cells that are otherwise capable of producing this protein. There is also a report that Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGFb) can stimulate Gli accumulation via mechanisms that may operate independently of Smoothened. Nuclear accumulation of Gli factors, in turn, influences transcriptional activity of Gli-target genes. Gli1 and Gli2 generally increase gene transcription, while Gli3 can either increase or decrease gene transcription depending on its post-translational modification.

Details about the Hh signaling pathway

Hh signaling may be initiated via autocrine, paracrine or endocrine mechanisms depending on whether the source of Hh ligands is the Hh-responsive cell itself, neighboring cells, or cells in distant tissues that release Hh ligands in membrane-associated particles with features of exosomes. Hh ligands are synthesized as propeptides and undergo auto-catalyzed cleavage to generate an N-terminal fragment that is further lipid-modified by cholesterol and prenylation before moving to the plasma membrane and being released into the extracellular space. Lipid modification limits the local diffusion of Hh ligands within tissues, but is not required for the ligands to engage Ptc, the trans-membrane spanning receptor on the surface of Hh-responsive cells [24, 63, 64]. Also, membranous particles that contain biologically-active Hh ligands have been purified from blood and bile, permitting Hh ligands that are produced in one locale to initiate signaling in distant sites [87]. Release of Hh ligands from Hh ligand producing cells is facilitated by the membrane-associated molecule, Dispatched, but the precise mechanisms involved remain somewhat obscure [24]. Maturation of Hh propeptides can also occur extracellularly. In the proximal GI tract, for example, digestive enzymes appear to catalyze cleavage of Hh ligands to generate biologically-active amino-terminal fragments [92].

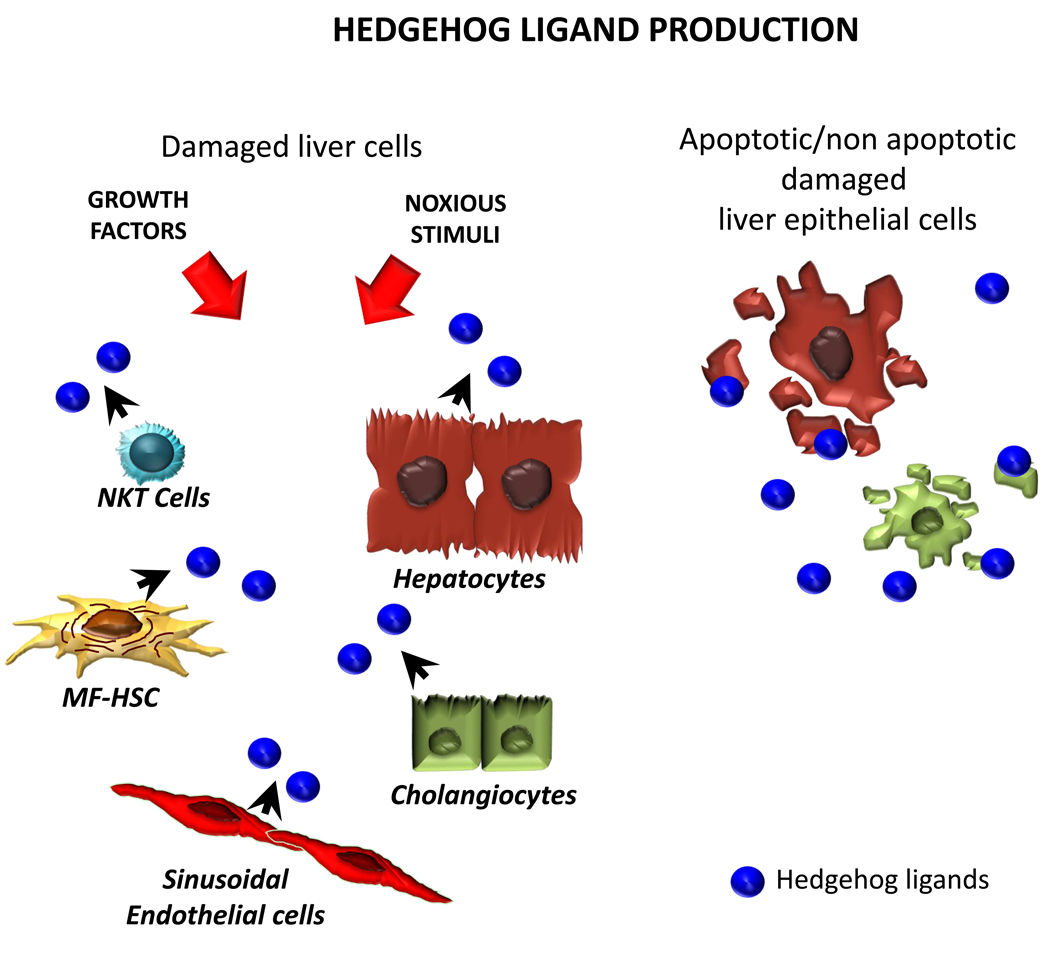

Various growth factors, cytokines, and certain types of cellular stress stimulate ligand-producing cells to express Hh ligands (Fig 2a). For example, epidermal growth factor (EGF) has been shown to induce gastric parietal cells to express Shh [76]; hepatic stellate cell expression of Shh was demonstrated to occur after treatment with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [90] or leptin [8]. In each case, induction of Shh was demonstrated to depend upon growth factor activation of PI3K/Akt signaling. Induction of Ihh expression was reported to occur in hepatocytes that were exposed to TGFb in concentrations that were sufficient to provoke eventual apoptosis [30]. Other stimuli that result in caspase 3 activation and eventual hepatocyte apoptosis also up-regulate expression of Shh and Ihh [33]. It remains to be determined if pro-apoptotic stimuli, like growth factors, engage PI3K/Akt to affect Hh ligand induction. However, the aggregate findings suggest that Hh ligand expression generally increases in response to various stimuli that promote tissue construction/remodeling. At present, the biological implications of producing distinct Hh ligands remain poorly understood. It appears that different Hh ligands are synthesized by different cell types/tissues (e.g., production of Dhh is particularly robust in ovary, testes, and peripheral nerves) [29, 61, 86]; Shh is generated by intestinal crypt cells, while Ihh is expressed by intestinal cells near the tips of villi)[3], but some cells are clearly capable of producing more than one type of ligand (e.g., hepatocytes, bile ductular cells, and hepatic stellate cells can each express both Shh and Ihh) [33, 56, 90]. Few head-to-head comparisons of different ligands have been reported. Although many similarities have been demonstrated [6, 39], different ligands exhibit variable potency for activating Hh signaling [45, 58], and one study reported that all of the effects of Shh and Ihh are not identical, even in a given type of Hh-responsive cell [2]

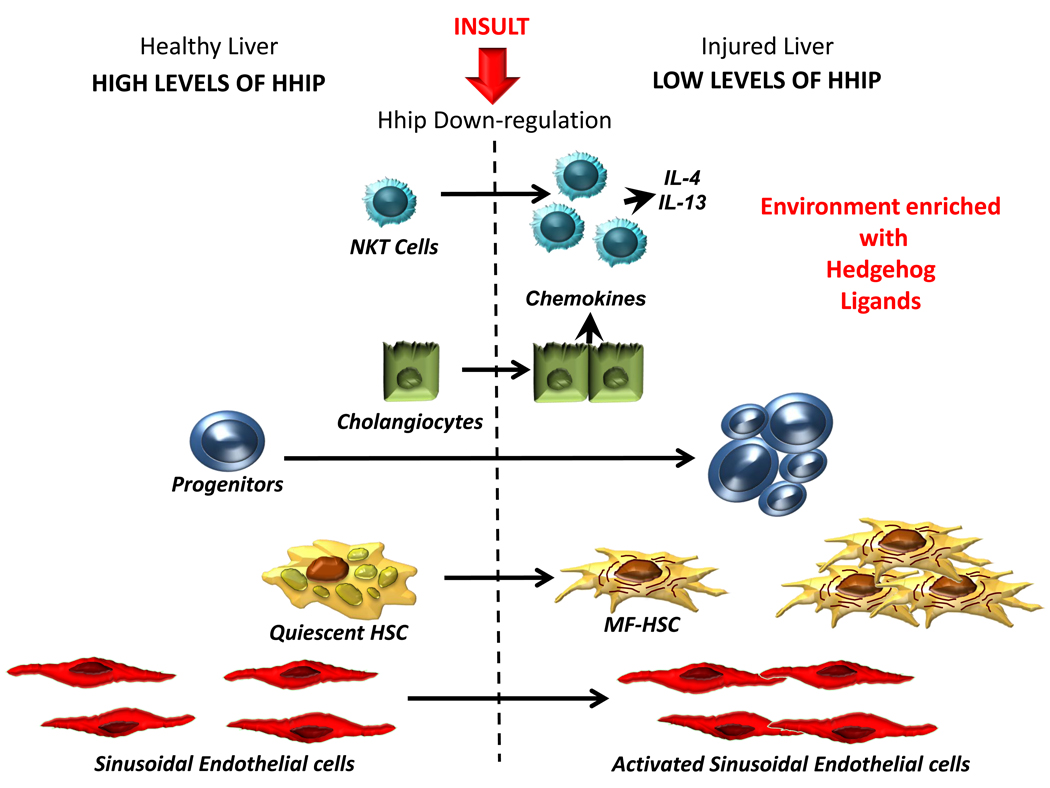

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Differential Activity of Hedgehog Pathway in Healthy and Injured Livers. Healthy livers express low levels of Hedgehog (Hh) ligands. Several types of resident liver cells are capable of producing Hh ligands, including hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, hepatic stellate cells (HSC), natural killer T (NKT) cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells. Ligand production can be stimulated by growth factors/cytokines, as well as by cytotoxic/apoptotic stress. Thus, diverse stimuli that promote liver regeneration/remodeling induce hepatic production of Hh ligands.

Figure 2b. Differential Activity of Hedgehog Pathway in Healthy and Injured Livers. Healthy livers express low levels of Hh ligands (a) and relatively high levels of Hh interacting protein (Hhip) (b), which binds to Hh ligands, preventing them from engaging receptors on Hh-responsive target cells. During liver injury, production of Hh ligands increases (Fig 2a) and Hhip is repressed, permitting ligand-receptor interaction and activation of the Hh signaling pathway in Hh-responsive cells. The latter include several types of resident liver cells, including NKT cells, cholangiocytes, progenitors and quiescent hepatic stellate cells (Q-HSC). Activation of Hh signaling in each of these cell types induces responses that contribute to fibrogenic repair. For example, Hh pathway activation stimulates growth of NKT cell populations and induces their production of pro-fibrogenic factors, such as IL4 and IL13. It also stimulates cholangiocyte growth and production of chemokines, including chemokines that recruit NKT cells and other inflammatory/immune cells to the liver. In addition, Hh ligands promote growth of liver progenitors and stimulate Q-HSC to transition to become myofibroblastic (MF)-HSC. The growth of MF-HSC is further stimulated by Hh pathway activity. Coupled with expansion of Hh-responsive ductular and progenitor populations, this contributes to the fibroductular reaction that often accompanies liver injury. Finally, Hh ligands activate liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, causing them to express adhesion factors and other mediators that contribute to vascular remodeling.

When Hh ligands engage Ptc, this inhibits its normal function, which is to repress Hh signaling by preventing activation of Smoothened (Fig 1). Emerging evidence suggests that Smoothened becomes localized to primary cilium during its activation, and that Ptc represses this process when Hh ligands are absent [11, 68]. The fact that certain inherited ciliary defects disrupt Hh signaling supports this concept [59, 66]. Other Hh signaling components, such as Gli3, are also deregulated in some ciliopathies. Because Gli3 normally represses transcriptional activation of certain Hh-regulated genes, ciliary dysfunction can also result in aberrant activation of various Hh targets [22]. Additional research is needed to clarify the mechanisms by which various ciliary structural components interact with components of the Hh pathway to modulate the propagation of Hh ligand-initiated signaling. At this point, however, it seems that ciliary dysfunction can both inhibit and activate Hh signaling [12, 85].

Efforts to map Hh pathway activity are further confounded by the fact that some of the components of the pathway, including Ptc (which is necessary to engage Hh ligands and activate signaling, but which also silences pathway activity when it is present in excess of Hh ligands), Gli1 (which generally activates transcription of Hh target genes), and Hh interacting protein (Hhip, a soluble antagonist of Hh ligands) are themselves the products of genes that are transcriptionally activated by Gli-family factors. Although Gli1 and Gli2 generally function as transcriptional activators, their actions are not fully redundant, suggesting that the two factors differ somewhat in their DNA binding affinities and/or ability to recruit transcriptional co-activators or repressors. The final Gli family member, Gli3, often represses gene transcription, but may also activate transcription depending upon its post-translational modification [84].

Further complexity is introduced by the fact that nuclear accumulation of Gli transcription factors is influenced by factors other than Hh ligands [28, 42]. For example, insulin-like growth factor has been shown to inhibit protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation of Gli1 in certain Hh-responsive cells. This inhibits subsequent Gli phosphorylation by GSK-3 beta and prevents its proteosomal degradation. The resultant stabilization of Gli-1 protein enhances Hh pathway activation [67]. TGF beta was recently reported to promote transcription of Gli2 without activating Smoothened, suggesting a “non-canonical” mechanism for modulating expression of Hh-regulated genes [14, 15]. Hh signaling components are also targets for epigenetic regulation, and appear to be particularly sensitive to changes in methylation status [47, 72, 80, 88, 89]. Conversely, Hh-sensitive transcription factors (i.e., Gli family members) also regulate transcription of pleiotropic TGF beta-target genes, such as snail [26, 36], and influence expression of factors that modulate Wnt signaling, including Wnt5a (a Wnt pathway activator) and soluble frizzled receptor-1 (sFRP1, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling) [37]. Suffice it to say, the Hh pathway is part of a complex signaling network that engages other fundamental cell fate regulators, such as TGFb and Wnt, to orchestrate global changes in the phenotypes of Hh-responsive cells [34, 35, 37, 38].

Hh helps to orchestrate liver growth and repair

Although there is little argument that TGF beta and Wnt are important regulators of growth and repair responses in adult livers [18, 48], the possibility that Hh was involved in these processes was not considered until relatively recently [52], and initial evidence supporting the concept was met with considerable skepticism. The latter likely reflected three main facts: 1) liver phenotypes had not been reported as major outcomes when various Hh signaling components were knocked-down experimentally in developing embryos, 2) Hh pathway activity had not been noted in healthy livers of adult rodents of humans, and thus, 3) there seemed to be little rationale for investigating Hh signaling in injured adult livers, so this had not been done systematically.

It is now evident, however, that complete silencing of Hh signaling in embryos interrupts formation of the nervous and cardiovascular systems, causing lethality before liver bud formation. Also, redundancies in the mechanisms that assure Hh pathway activation permit partial compensation for incomplete, or later, disruption of Hh signaling during liver development, resulting in relatively subtle hepatic defects that are often overlooked in the context of devastating neurological, cardiovascular, and/or musculoskeletal deformities [27]. It has also become apparent that Hh ligands are expressed by the primitive ventral endoderm that ultimately gives rise to hepatic progenitors [20], and that transcriptional activation of foxa2 (a transcription factor that is required for hepatic specification of this endoderm[43]) is directly regulated by Gli factors [70]. More recent data further support the molecular evidence for Hh pathway involvement in liver development: 1) transcriptional activation of ptc has been demonstrated in embryonic livers of day 11.5 ptc-LacZ reporter mice [75], 2) fetal liver cells that were harvested from d11.5 WT mouse embryos and purified by flow cytometry proliferated in response to Hh ligands and Hh pathway activity was required for optimal viability in hepatoblasts, but negatively regulated differentiation of such liver progenitors at later developmental stages [23], 3) cells that produce and respond to Hh ligands were localized to the ductal plates of developing human livers and Smoothened inhibitors dramatically reduced the viability of clonally-derived human fetal hepatoblasts in culture [75], 4) various ciliopathies that disrupt Hh signaling exhibit a significant hepatic phenotype (cystic malformations of the intrahepatic biliary tree and liver fibrosis) [12, 59, 66, 85], and 5) the Hh pathway regulates the growth of hepatoblastomas, a progenitor-derived tumor that is the most common type of primary liver cancer in very young children [57].

An explanation for the general lack of Hh pathway activity in healthy adult livers has also emerged. First, little, if any, production of Hh ligands is demonstrable in healthy adult liver cells [32, 53, 56]. Second, liver sinusoidal cells (e.g., endothelial cells and quiescent hepatic stellate cells) strongly express Hhip, which interacts with soluble Hh ligands and prevents them from engaging Ptc [9, 10, 73, 90]}. Third, Hh pathway activity is progressively silenced during the process of liver epithelial cell maturation, such that expression of ptc1 is exponentially lower in healthy mature hepatocytes than in bipotent hepatic progenitors, and the latter is likewise reduced compared to that of multipotent endodermal progenitors [75]. Healthy adult livers harbor relatively small progenitor populations, and these tend to localize along canals of Hering [93], where immunohistochemical analysis has now demonstrated expression of Hh ligands, Hh-regulated transcription factors, and other Hh-responsive genes, in healthy adult human and rodent livers [17, 32, 53, 56].

Finally, improved understanding of mechanisms that regulate Hh ligand production predicts that Hh pathway activation would likely occur when major re-construction of the liver is required in adulthood. First, various growth factors for hepatocytes and liver nonparenchymal cells induce expression of Shh and Ihh (Fig 2a). Consistent with these data, hepatic expression of Shh and Ihh increases significantly after 70% partial hepatectomy (PH) which provides a tremendous stimulus for liver regeneration [51]. Noxious stimuli that provoke compensatory hepatic repair also stimulate liver cells to produce Hh ligands. For example, Shh expression has been localized to ballooned hepatocytes in patients with NASH[77], while Ihh expression has been demonstrated in bile ductular epithelial cells of patients with destructive cholangiopathies, such as primary biliary cirrhosis [32, 53, 56]. Second, it has been shown that membrane fragments released from apoptotic and non-apoptotic liver epithelial cells harbor biologically active Hh ligands [87]. This finding, coupled with a third line of evidence demonstrating dramatic down-regulation of Hhip expression at early stages of myofibroblastic trans-differentiation of hepatic stellate cells (HSC) and during activation of sinusoidal endothelial cells (SEC) [9, 87, 90] predicts that Hh ligands derived from liver epithelial cells would be capable of activating Hh signaling in neighboring stromal cells via paracrine mechanisms. Consistent with this concept, types of Hh-responsive cells that rely upon Hh signaling for optimal viability and growth (e.g., myofibroblastic (MF)-HSC, activated SEC, and immature liver epithelial cells, including bipotent liver progenitors) are relatively inconspicuous in healthy adult livers, but accumulate in livers that are producing high levels of Hh ligands, but relatively little Hhip [17, 53, 77] (Fig 2b). Immunohistochemistry of diseased human livers, such as those with chronic viral hepatitis [60], alcoholic liver disease, or NAFLD [17, 30, 31, 77], confirms that Hh-regulated transcription factors (e.g., Gli2) co-localize with markers of activated SEC (e.g., CD31), MF (alpha-smooth muscle actin), and immature liver epithelial cells (e.g., CK7), and reveals that numbers of Hh-responsive cells closely parallels the level of Hh ligand production. Moreover, both hepatic production of Hh ligands and accumulation of Hh responsive cells generally increase with the severity of liver damage and fibrosis [17, 31, 53].

Accumulating evidence also demonstrates that hepatic accumulation of Hh-target cells is not merely an epi-phenomenon that accompanies liver re-construction. Rather, such cells actively contribute to regenerative/remodeling processes in adult livers. Treating healthy mice with Smoothened antagonists to inhibit Hh signaling after PH, for example, significantly reduced hepatic accumulation of progenitors and MF, inhibited proliferation of hepatocytes and cholangiocytes, blocked liver regeneration, and resulted in death of most mice by 72 h post-PH [51]. Conversely, mice with haploinsufficiency of ptc exhibited sustained over-activation of the Hh pathway, accumulated greater numbers of MF and immature liver cells, and developed much worse fibrosis during liver injury [56, 77]. Together, these findings suggest that transient activation of the Hh pathway is necessary for adult livers to regenerate after an acute injury, but that sustained increases in Hh signaling (as occurs when injury is persistent) perpetuate the expansion of cell types, such as MF, activated SEC and immature liver epithelial cells, which are involved in the pathogenesis of cirrhosis. This logic helps to explain why chronic liver injury is a much greater risk factor for cirrhosis than acute liver injury.

Determining the relative significance of Hh as a regulator of adult liver growth and repair

As discussed earlier, Hh interacts with several other key signaling pathways to modulate cell fate decisions. Thus, it is clearly not the sole pathway that dictates how adult livers respond to situations that provoke growth and/or repair. Delineating the hierarchy of signal transduction that drives construction of liver tissue is also challenging because the relative importance of any given pathway might differ according to cell type and/or differentiation status, and would also be expected to vary with moment-to-moment changes in levels of factors that promote, as opposed to inhibit, each pathway. Nevertheless, experimental evidence suggests that once activated in liver tissue, the Hh pathway generally tends to auto-amplify as long as Hh ligands persist, despite “built-in” mechanisms in individual cells which would be predicted to constrain further Hh pathway activation (i.e., Hh-driven induction of Ptc and Hhip). This finding may be explained, in part, by the fact that Hh pathway activation in resident Hh-responsive liver cells gradually increases the net number of Hh ligand-producing cells and Hh-responsive cells in the liver. For example, Hh ligands stimulate trans-differentiation of resident quiescent HSC into MF-HSC, as well as the growth of MF-HSC populations that produce and respond to Hh ligands [73, 90]. Similarly, Hh ligands promote biliary epithelial cell expression of chemokines (e.g., CXCL16) that recruit subpopulations of Hh ligand producing- and Hh-responsive immune cells (e.g., NKT cells) into liver [55, 78, 79]. It has also been suggested that expanding populations of Hh responsive cells enrich the hepatic micro-environment with other factors that potentiate Hh pathway activity by stimulating further production of Hh ligands (e.g., PDGF and TGF beta) [52], or by acting down-stream of Smoothened to stabilize the activity of Hh-responsive transcription factors, such as Gli1 and Gli2 (e.g., IGF-1, TGF beta),as discussed earlier. At some point, regenerative/repair responses that were initially triggered by Hh signaling might also proceed independently of further Hh pathway activity. This possibility is supported by evidence that Hh pathway activation stimulates certain types of lymphocytes to produce other fibrogenic factors (e.g., IL4, IL13) [78, 79].

More research is needed to characterize the types of cells, cell-type specific responses, and particular aspects of liver reconstruction that are most dependent upon Hh signaling in order to judge the potential merits of manipulating Hh pathway activity to improve adult liver repair. In liver, such research is in its infancy. None-the-less, progress has been made regarding apoptosis regulation by Hh signaling, and Hh pathway control of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions, in certain liver cell types. Hence, the final two sections will summarize existing information about those topics.

Hh activation regulates pro-survival pathways in several types of liver cells

Growing evidence reveals that Hh signaling plays a key and conserved role across multiple liver cell types to inhibit hepatic apoptosis. The signaling mechanisms involved have been best delineated in bile ductular cells (cholangiocytes). Cholangiocytes display differential sensitivity to apoptosis depending on their pathophysiologic state. While apoptosis increases in various cholangiopathies, subpopulations of ductular cells exhibit reduced apoptotic activity in liver diseases that are accompanied by fibroductular reactions [4, 46]. Malignant cholangiocytes also tend to be relatively protected from apoptosis [21, 65, 82]. Studies of apoptotic signaling in cholangiocytes have identified TRAIL and its death receptors, DR4 and DR5, as major initiators of apoptosis [41, 81], and the Bcl-2 family member, Mcl-1, as a key anti-apoptotic factor [49]. Cholangiocytes are Hh-responsive cells and it was demonstrated that Hh ligands reduce cholangiocyte apoptosis [56]. Interestingly, this may reflect the ability of Hh-regulated transcription factors to modulate expression of DR4 and Mcl-1. The Hh-inducible transcription factor, Gli3, binds to the DR4 promoter and represses DR4 transcription in a Hh-dependent manner [41]. The Hh pathway also regulates expression of Mcl-1 but the mechanism involved is somewhat complex. In cholangiocarcinoma cells, translation of Mcl-1 is repressed by miR-29b binding to the 3’UTR of mcl-1 mRNA [50]. Hence, factors that reduce miR-29b expression lead to increased synthesis of Mcl-1 protein. Functional Gli binding sites have been demonstrated in the miR-29b promoter and Gli represses transcriptional activity of miR-29b [50]. Thus repressive actions of Hh-induced transcription factors result in ultimate increases in cellular content of Mcl-1 protein. The combined effects of Hh pathway activation on DR4 and Mcl-1 protect cholangiocytes from apoptosis by reducing expression of the death receptor, DR4 while increasing expression of the anti-apoptotic factor, Mcl-1.

In addition to cholangiocytes, Hh signaling has been shown to inhibit apoptosis in HSC [56]. Further research is needed to determine if this occurs via mechanisms that involve death receptor signaling and Mcl-1, as occurs in cholangiocytes.

The Hh pathway also promotes the viability of healthy liver epithelial progenitors [75] and certain types of malignant hepatocytes. Investigators studying hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs; which represent the majority of hepatic cancers) found that inhibition of hedgehog signaling (using Shh neutralizing antibodies) in HCC cell lines with detectable endogenous Hh signaling (Hep3B, Huh7 and PLC/PRF/5) decreases expression of hedgehog target genes and induces apoptosis [25]. Consistent with this, SMO antagonism using KAAD-cyclopamine recapitulates this effect [25, 74]. As expected, modulation of Hh signaling in HCC cells that display no endogenous Hh signaling (HCC36 and HepG2) has no effect on cellular viability, showing results are specific for the Hh pathway. Similarly, recent studies reveal that Hh signaling is activated in hepatoblastoma (HB), the most common liver tumor in childhood [16]. Deregulation of the Hh pathway appears to be caused by methylation of the inhibitory Hhip locus in a large number of HB patients [16]. Pharmacologic inhibition of Hh signaling with cyclopamine had a strong inhibitory effect on cell proliferation of HB cell lines and caused a massive induction of apoptosis [16].

Hh pathway activation promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions in biliary epithelial cells and hepatic stellate cells

Many types of cells are capable of considerable plasticity, particularly when immature. For example, gastrulation (one of the earliest events in embryogenesis) involves disaggregation of epiblast epithelial cells and their invasion into adjacent stroma. Subsequent construction of various tissues requires carefully orchestrated waves of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and reciprocal mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET). Cells derived from each of the three germ layers (i.e., endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm) are capable of undergoing EMT/MET during embryogenesis, reversibly acquiring an epithelial phenotype (defined as polarized and adherent to adjacent cells) or a mesenchymal phenotype (defined as migratory and invasive) [1]. Recently published studies in mouse embryonic fibroblasts demonstrate that the reversibility of such transitions changes over time because they trigger progressive cascades of gene expression. Hence, cells which are early in the process are most plastic. Never-the-less, fibroblastic cells that are no longer transitional can be coaxed to acquire epithelial characteristics transiently and eventually become pluripotent progenitors that generate all three germ layers by enforcing over-expression of a small group of transcription factors. Notably, however, exposing mesenchymal cells that harbored all of the reprogramming transcription factors to exogenous stimuli that activated TGFbeta signaling prevented them from undergoing MET and aborted their reprogramming to pluripotent progenitor cells, proving that extrinsic factors strictly gate cell fate decisions even in cells that are intrinsically capable of enormous plasticity [44, 62, 69].

These exciting findings suggest mechanisms that permit multipotent progenitors to persist in selected “niches” in various adult tissues, and may be particularly relevant to regenerative/repair responses in adult livers because the latter typically harbor small numbers of (at least) bipotent progenitors [93]. There is conflicting evidence that such bipotent liver progenitor cells exhibit characteristics of transitional cells [7, 13, 40, 71, 91] However, it has already been demonstrated that Hh and TGF beta (two of the main signal transduction pathways that modulate EMT/MET in developing embryos [5]) influence EMT/MET in cells that are involved in adult liver repair, including immature ductular cells [54] and hepatic stellate cells [9, 10].

The signaling mechanisms by which Hh induces EMT in adult liver cells have been studied most systematically in HSC. Freshly isolated, quiescent (Q)-HSC have some characteristics of mesenchymal cells, i.e., they express desmin and certain mesenchyme-associated transcription factors. However, expression of most other typical myofibroblast-associated genes, including alpha smooth muscle actin (a-sma) and collagen 1a1, is conspicuously absent. Rather, gene expression profiles in Q-HSC are more consistent with those of adipocytic/neuroepithelioid cells, characterized by easily demonstrated expression of Peroxisome proliferator activating receptor (PPAR)-γ, Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), E-cadherin, desmoplakin, and certain epithelial cytokeratins that are also expressed by liver progenitors and biliary epithelial cells (Ker7 and Ker19). Q-HSC also express high levels of Hhip, but mRNAs for Hh ligands and other Hh target genes (e.g., Glis) are barely detectable. Within 24 h of culture in serum-containing medium, Hhip expression falls by 90%, followed by HSC production of Shh and Hh pathway activation (evidenced by accumulation of Gli mRNAs). As Hh pathway activation occurs, the cells down-regulate expression of all quiescence/epithelial markers and gradually up-regulate expression of myofibroblast associated genes, including a-sma, coll1a1, vimentin, fibronectin, S-100A4, and TGFbeta1, as well as snail, a Gli-responsive transcription factor that is known to mediate TGFbeta-initiated EMT [9]. Transition of Q-HSC to MF-HSC is also accompanied by reduced expression of bmp7 and its target, id2. Down-regulation of bmp7 and id 2 has been shown to permit repression of E-cadherin expression and occurs in other cells as they undergo EMT [19, 83]. Conversely, induction of bmp7 mediates up-regulation of E-cadherin during reprogramming of MEFs to induced pluripotent stem cells [44, 62, 69]. Days after primary HSC acquire a fully myofibroblastic phenotype (or years after this phenotype was acquired in clonal HSC lines), mesenchymal gene expression can be silenced and quiescence/epithelial gene expression restored by treating cells with a Smoothened inhibitor, cyclopamine, to abrogate Hh signaling. Hh pathway inhibition restores expression of bmp7, id2, E-cadherin, desmoplakin, and other epithelial/quiescence markers, represses expression of the mesenchymal gene program, and causes loss of the typical migratory/invasive phenotype of MF-HSC [9]. EMT/MET in HSC involves cytoskeletal reorganization and is accompanied by changes in activity Rac1, a small cytoskeletal-associated GTPase. Manipulating Rac1 activity in cultured HSC with adenoviral vectors also dramatically influences Hh signaling and EMT/MET, with increased Rac1 stimulating EMT and Rac1 repression promoting MET [10]. Manipulating Rac1 activity in rodents evoked similar responses and resulted in significant alterations in liver fibrosis when the animals were challenged with either bile duct ligation or carbon tetrachloride [10]. Emerging evidence suggests that Hh-dependent alterations in epithelial/mesenchymal gene expression may be a conserved response to other fibrogenic stimuli. For example, it occurs when HSC are treated with leptin and is necessary for leptin to repress HSC quiescence and promote acquisition/maintenance of the MF-HSC phenotype [8].

Summary

Emerging data indicate that hedgehog signaling mediates both adaptive and maladaptive responses to liver injury, depending upon the balance between its actions as a regulator of progenitor cell growth and its ability to promote liver inflammation and fibrogenic repair. Synthesis of hedgehog ligands is stimulated by diverse factors that trigger liver regeneration, including both liver cell mitogens and liver cell stressors. These Hh ligands, in turn, are released from ligand-producing cells into the local environment where they engage receptors on Hh-responsive cells. The latter include progenitor cells, hepatic stellate cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells and certain types of resident hepatic immune cells. In general, Hh ligands function as trophic factors and promote the viability of Hh-target cells. This enhances the outgrowth of liver progenitor populations, triggers tissue remodeling, and promotes liver regeneration. However, Hh ligands also stimulate certain cell types (e.g., hepatic stellate cells, immature liver epithelial cells) to acquire a less epithelial and more mesenchymal state during which such cells generate inflammatory mediators and scar tissue. By promoting EMT (while inhibiting MET), Hh pathway activation, therefore, induces liver fibrogenesis. Hence, excessive or persistent Hh pathway activity actually aborts successful regeneration of damaged liver tissue and contributes to the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Clearly, further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms of hedgehog-mediated hepatic repair to preferentially activate therapeutically beneficial pathways to treat chronic liver diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, Bronner-Fraser M, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1438–1449. doi: 10.1172/JCI38019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adolphe C, Narang M, Ellis T, Wicking C, Kaur P, Wainwright B. An in vivo comparative study of sonic, desert and Indian hedgehog reveals that hedgehog pathway activity regulates epidermal stem cell homeostasis. Development. 2004;131(20):5009–5019. doi: 10.1242/dev.01367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alinger B, Kiesslich T, Datz C, Aberger F, Strasser F, Berr F, et al. Hedgehog signaling is involved in differentiation of normal colonic tissue rather than in tumor proliferation. Virchows Arch. 2009;454(4):369–379. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0753-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvaro D, Mancino MG. New insights on the molecular and cell biology of human cholangiopathies. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29(1–2):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baum B, Settleman J, Quinlan MP. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states in development and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19(3):294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop B, Aricescu AR, Harlos K, O'Callaghan CA, Jones EY, Siebold C. Structural insights into hedgehog ligand sequestration by the human hedgehog-interacting protein HHIP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(7):698–703. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu CC, Sheu JC, Chen CH, Lee CZ, Chiou LL, Chou SH, et al. Global gene expression profiling reveals a key role of CD44 in hepatic oval-cell reaction after 2-AAF/CCI4 injury in rodents. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;132(5):479–489. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0634-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi S, Diehl AM. Leptin and hedgehog interact to regulate myofibroblastic phenotype of hepatic stellate cells submitted [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi SS, Omenetti A, Witek RP, Moylan CA, Syn WK, Jung Y, et al. Hedgehog pathway activation and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions during myofibroblastic transformation of rat hepatic cells in culture and cirrhosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297(6):G1093–G1106. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00292.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi SS, Witek RP, Yang L, Omenetti A, Syn WK, Moylan CA, et al. Activation of Rac1 promotes hedgehog-mediated acquisition of the myofibroblastic phenotype in rat and human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 52(1):278–290. doi: 10.1002/hep.23649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbit KC, Aanstad P, Singla V, Norman AR, Stainier DY, Reiter JF. Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature. 2005;437(7061):1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Angelo A, Franco B. The dynamic cilium in human diseases. Pathogenetics. 2009;2(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1755-8417-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.del Castillo G, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Carmona-Cuenca I, Fernandez M, Sanchez A, Fabregat I. Isolation and characterization of a putative liver progenitor population after treatment of fetal rat hepatocytes with TGF-beta. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215(3):846–855. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dennler S, Andre J, Alexaki I, Li A, Magnaldo T, ten Dijke P, et al. Induction of sonic hedgehog mediators by transforming growth factor-beta: Smad3-dependent activation of Gli2 and Gli1 expression in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67(14):6981–6986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dennler S, Andre J, Verrecchia F, Mauviel A. Cloning of the human GLI2 Promoter: transcriptional activation by transforming growth factor-beta via SMAD3/beta-catenin cooperation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(46):31523–31531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eichenmuller M, Gruner I, Hagl B, Haberle B, Muller-Hocker J, von Schweinitz D, et al. Blocking the hedgehog pathway inhibits hepatoblastoma growth. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):482–490. doi: 10.1002/hep.22649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleig SV, Choi SS, Yang L, Jung Y, Omenetti A, VanDongen HM, et al. Hepatic accumulation of Hedgehog-reactive progenitors increases with severity of fatty liver damage in mice. Lab Invest. 2007;87(12):1227–1239. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gressner OA, Gressner AM. Connective tissue growth factor: a fibrogenic master switch in fibrotic liver diseases. Liver Int. 2008;28(8):1065–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gressner OA, Weiskirchen R, Gressner AM. Evolving concepts of liver fibrogenesis provide new diagnostic and therapeutic options. Comp Hepatol. 2007;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harmon EB, Ko AH, Kim SK. Hedgehog signaling in gastrointestinal development and disease. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2(1):67–82. doi: 10.2174/1566524023363130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harnois DM, Que FG, Celli A, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ. Bcl-2 is overexpressed and alters the threshold for apoptosis in a cholangiocarcinoma cell line. Hepatology. 1997;26(4):884–890. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK. Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet. 2005;1(4):e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirose Y, Itoh T, Miyajima A. Hedgehog signal activation coordinates proliferation and differentiation of fetal liver progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(15):2648–2657. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooper JE, Scott MP. Communicating with Hedgehogs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(4):306–317. doi: 10.1038/nrm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang S, He J, Zhang X, Bian Y, Yang L, Xie G, et al. Activation of the hedgehog pathway in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(7):1334–1340. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huber MA, Kraut N, Beug H. Molecular requirements for epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumor progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17(5):548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingham PW, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes Dev. 2001;15(23):3059–3087. doi: 10.1101/gad.938601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins D. Hedgehog signalling: emerging evidence for non-canonical pathways. Cell Signal. 2009;21(7):1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Signals that determine Schwann cell identity. J Anat. 2002;200(4):367–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung Y, Brown KD, Witek RP, Omenetti A, Yang L, Vandongen M, et al. Accumulation of hedgehog-responsive progenitors parallels alcoholic liver disease severity in mice and humans. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1532–1543. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung Y, Diehl AM. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis pathogenesis: role of repair in regulating the disease progression. Dig Dis. 28(1):225–228. doi: 10.1159/000282092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung Y, McCall SJ, Li YX, Diehl AM. Bile ductules and stromal cells express hedgehog ligands and/or hedgehog target genes in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45(5):1091–1096. doi: 10.1002/hep.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung Y, Witek RP, Syn WK, Choi SS, Omenetti A, Premont R, et al. Signals from dying hepatocytes trigger growth of liver progenitors. Gut. 59(5):655–665. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.204354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katoh M, Katoh M. Integrative genomic analyses of ZEB2: Transcriptional regulation of ZEB2 based on SMADs, ETS1, HIF1alpha, POU/OCT, and NF-kappaB. Int J Oncol. 2009;34(6):1737–1742. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katoh M, Katoh M. Transcriptional mechanisms of WNT5A based on NF-kappaB, Hedgehog, TGFbeta, and Notch signaling cascades. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23(6):763–769. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katoh Y, Katoh M. Hedgehog signaling, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and miRNA (review) Int J Mol Med. 2008;22(3):271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katoh Y, Katoh M. Hedgehog target genes: mechanisms of carcinogenesis induced by aberrant hedgehog signaling activation. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9(7):873–886. doi: 10.2174/156652409789105570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katoh Y, Katoh M. Integrative genomic analyses on GLI1: positive regulation of GLI1 by Hedgehog-GLI, TGFbeta-Smads, and RTK-PI3K-AKT signals, and negative regulation of GLI1 by Notch-CSL-HES/HEY, and GPCR-Gs-PKA signals. Int J Oncol. 2009;35(1):187–192. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kavran JM, Ward MD, Oladosu OO, Mulepati S, Leahy DJ. All mammalian hedgehog proteins interact with CDO and BOC in a conserved manner. J Biol Chem. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koenig S, Probst I, Becker H, Krause P. Zonal hierarchy of differentiation markers and nestin expression during oval cell mediated rat liver regeneration. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;126(6):723–734. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurita S, Mott JL, Almada LL, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Sun SY, et al. GLI3-dependent repression of DR4 mediates hedgehog antagonism of TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauth M, Toftgard R. Non-canonical activation of GLI transcription factors: implications for targeted anti-cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(20):2458–2463. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.20.4808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee CS, Friedman JR, Fulmer JT, Kaestner KH. The initiation of liver development is dependent on Foxa transcription factors. Nature. 2005;435(7044):944–947. doi: 10.1038/nature03649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li R, Liang J, Ni S, Zhou T, Qing X, Li H, et al. A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 7(1):51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez-Chinchilla P, Riobo NA. Purification and bioassay of hedgehog ligands for the study of cell death and survival. Methods Enzymol. 2008;446:189–204. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marzioni M, Fava G, Alvaro D, Alpini G, Benedetti A. Control of cholangiocyte adaptive responses by visceral hormones and neuropeptides. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36(1):13–22. doi: 10.1007/s12016-008-8090-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maurange C, Paro R. A cellular memory module conveys epigenetic inheritance of hedgehog expression during Drosophila wing imaginal disc development. Genes Dev. 2002;16(20):2672–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.242702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monga SP. Role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in liver metabolism and cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mott JL, Kobayashi S, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. mir-29 regulates Mcl-1 protein expression and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2007;26(42):6133–6140. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mott JL, Kurita S, Cazanave SC, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Fernandez-Zapico ME. Transcriptional suppression of mir-29b-l/mir-29a promoter by c-Myc, hedgehog, and NF-kappaB. J Cell Biochem. 110(5):1155–1164. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ochoa B, Syn WK, Delgado I, Karaca GF, Jung Y, Wang J, et al. Hedgehog signaling is critical for normal liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology. 51(5):1712–1723. doi: 10.1002/hep.23525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Omenetti A, Diehl AM. The adventures of sonic hedgehog in development and repair. II. Sonic hedgehog and liver development, inflammation, and cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294(3):G595–G598. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00543.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Omenetti A, Popov Y, Jung Y, Choi SS, Witek RP, Yang L, et al. The hedgehog pathway regulates remodelling responses to biliary obstruction in rats. Gut. 2008;57(9):1275–1282. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.148619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Omenetti A, Porrello A, Jung Y, Yang L, Popov Y, Choi SS, et al. Hedgehog signaling regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition during biliary fibrosis in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(10):3331–3342. doi: 10.1172/JCI35875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Omenetti A, Syn WK, Jung Y, Francis H, Porrello A, Witek RP, et al. Repair-related activation of hedgehog signaling promotes cholangiocyte chemokine production. Hepatology. 2009;50(2):518–527. doi: 10.1002/hep.23019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Omenetti A, Yang L, Li YX, McCall SJ, Jung Y, Sicklick JK, et al. Hedgehog-mediated mesenchymal-epithelial interactions modulate hepatic response to bile duct ligation. Lab Invest. 2007;87(5):499–514. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oue T, Yoneda A, Uehara S, Yamanaka H, Fukuzawa M. Increased expression of the hedgehog signaling pathway in pediatric solid malignancies. J Pediatr Surg. 45(2):387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pathi S, Pagan-Westphal S, Baker DP, Garber EA, Rayhorn P, Bumcrot D, et al. Comparative biological responses to human Sonic, Indian, and Desert hedgehog. Mech Dev. 2001;106(1–2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pedersen LB, Rosenbaum JL. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) role in ciliary assembly, resorption and signalling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:23–61. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pereira TA, Diehl AM. Hedgehog pathway activation regulates response to chronic viral hepatitis. Lab Invest. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pierucci-Alves F, Clark AM, Russell LD. A developmental study of the Desert hedgehog-mouse testis. Biol Reprod. 2001;65(5):1392–1402. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.5.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Polo JM, Hochedlinger K. When fibroblasts MET iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 7(1):5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Porter JA, von Kessler DP, Ekker SC, Young KE, Lee JJ, Moses K, et al. The product of hedgehog autoproteolytic cleavage active in local and long-range signalling. Nature. 1995;374(6520):363–366. doi: 10.1038/374363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA. Cholesterol modification of hedgehog signaling proteins in animal development. Science. 1996;274(5285):255–259. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Que FG, Phan VA, Phan VH, Celli A, Batts K, LaRusso NF, et al. Cholangiocarcinomas express Fas ligand and disable the Fas receptor. Hepatology. 1999;30(6):1398–1404. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quinlan RJ, Tobin JL, Beales PL. Modeling ciliopathies: Primary cilia in development and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;84:249–310. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riobo NA, Lu K, Ai X, Haines GM, Emerson CP., Jr Phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Akt are essential for Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(12):4505–4510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504337103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. Patched1 regulates hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science. 2007;317(5836):372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1139740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Golipour A, David L, Sung HK, Beyer TA, Datti A, et al. Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 7(1):64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sasaki H, Hui C, Nakafuku M, Kondoh H. A binding site for Gli proteins is essential for HNF-3beta floor plate enhancer activity in transgenics and can respond to Shh in vitro. Development. 1997;124(7):1313–1322. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.7.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmelzer E, Wauthier E, Reid LM. The phenotypes of pluripotent human hepatic progenitors. Stem Cells. 2006;24(8):1852–1858. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shindo N, Sakai A, Arai D, Matsuoka O, Yamasaki Y, Higashinakagawa T. The ESC-E(Z) complex participates in the hedgehog signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327(4):1179–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sicklick JK, Li YX, Choi SS, Qi Y, Chen W, Bustamante M, et al. Role for hedgehog signaling in hepatic stellate cell activation and viability. Lab Invest. 2005;85(11):1368–1380. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sicklick JK, Li YX, Jayaraman A, Kannangai R, Qi Y, Vivekanandan P, et al. Dysregulation of the Hedgehog pathway in human hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(4):748–757. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sicklick JK, Li YX, Melhem A, Schmelzer E, Zdanowicz M, Huang J, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains resident hepatic progenitors throughout life. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(5):G859–G870. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00456.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stepan V, Ramamoorthy S, Nitsche H, Zavros Y, Merchant JL, Todisco A. Regulation and function of the sonic hedgehog signal transduction pathway in isolated gastric parietal cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(16):15700–15708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Syn WK, Jung Y, Omenetti A, Abdelmalek M, Guy CD, Yang L, et al. Hedgehog-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fibrogenic repair in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(4):1478–1488. e1478. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Syn WK, Oo YH, Pereira TA, Karaca GF, Jung Y, Omenetti A, et al. Accumulation of natural killer T cells in progressive nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 51(6):1998–2007. doi: 10.1002/hep.23599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Syn WK, Witek RP, Curbishley SM, Jung Y, Choi SS, Enrich B, et al. Role for hedgehog pathway in regulating growth and function of invariant NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(7):1879–1892. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tada M, Kanai F, Tanaka Y, Tateishi K, Ohta M, Asaoka Y, et al. Down-regulation of hedgehog-interacting protein through genetic and epigenetic alterations in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(12):3768–3776. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takeda K, Kojima Y, Ikejima K, Harada K, Yamashina S, Okumura K, et al. Death receptor 5 mediated-apoptosis contributes to cholestatic liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(31):10895–10900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802702105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Taniai M, Grambihler A, Higuchi H, Werneburg N, Bronk SF, Farrugia DJ, et al. Mcl-1 mediates tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(10):3517–3524. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Valcourt U, Kowanetz M, Niimi H, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. TGF-beta and the Smad signaling pathway support transcriptomic reprogramming during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transition. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(4):1987–2002. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Varjosalo M, Li SP, Taipale J. Divergence of hedgehog signal transduction mechanism between Drosophila and mammals. Dev Cell. 2006;10(2):177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Veland IR, Awan A, Pedersen LB, Yoder BK, Christensen ST. Primary cilia and signaling pathways in mammalian development, health and disease. Nephron Physiol. 2009;111(3):39–53. doi: 10.1159/000208212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wijgerde M, Ooms M, Hoogerbrugge JW, Grootegoed JA. Hedgehog signaling in mouse ovary: Indian hedgehog and desert hedgehog from granulosa cells induce target gene expression in developing theca cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146(8):3558–3566. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Witek RP, Yang L, Liu R, Jung Y, Omenetti A, Syn WK, et al. Liver Cell-Derived Microparticles Activate Hedgehog Signaling and Alter Gene Expression in Hepatic Endothelial Cells. Gastroenterology. 2008 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wolf I, Bose S, Desmond JC, Lin BT, Williamson EA, Karlan BY, et al. Unmasking of epigenetically silenced genes reveals DNA promoter methylation and reduced expression of PTCH in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;105(2):139–155. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yakushiji N, Suzuki M, Satoh A, Sagai T, Shiroishi T, Kobayashi H, et al. Correlation between Shh expression and DNA methylation status of the limb-specific Shh enhancer region during limb regeneration in amphibians. Dev Biol. 2007;312(1):171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang L, Wang Y, Mao H, Fleig S, Omenetti A, Brown KD, et al. Sonic hedgehog is an autocrine viability factor for myofibroblastic hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2008;48(1):98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yovchev MI, Grozdanov PN, Zhou H, Racherla H, Guha C, Dabeva MD. Identification of adult hepatic progenitor cells capable of repopulating injured rat liver. Hepatology. 2008;47(2):636–647. doi: 10.1002/hep.22047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zavros Y, Waghray M, Tessier A, Bai L, Todisco A, D LG, et al. Reduced pepsin A processing of sonic hedgehog in parietal cells precedes gastric atrophy and transformation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(46):33265–33274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang L, Theise N, Chua M, Reid LM. The stem cell niche of human livers: symmetry between development and regeneration. Hepatology. 2008;48(5):1598–1607. doi: 10.1002/hep.22516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]