Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) is an important intracellular messenger underlying cell physiology. Ca2+ channels are the main entry route for Ca2+ into excitable cells, and regulate processes such as neurotransmitter release and neuronal outgrowth. Neuronal Calcium Sensor-1 (NCS-1) is a member of the Calmodulin superfamily of EF-hand Ca2+ sensing proteins residing in the subfamily of NCS proteins. NCS-1 was originally discovered in Drosophila as an overexpression mutant (Frequenin), having an increased frequency of Ca2+-evoked neurotransmission. NCS-1 is N-terminally myristoylated, can bind intracellular membranes, and has a Ca2+ affinity of 0.3 μM. Over 10 years ago it was discovered that NCS-1 overexpression enhances Ca2+-evoked secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. The mechanism was unclear, but there was no apparent direct effect on the exocytotic machinery. It was revealed, again in chromaffin cells, that NCS-1 regulates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Cavs) in G-Protein Coupled Receptor (GPCR) signaling pathways. This work in chromaffin cells highlighted NCS-1 as an important modulator of neurotransmission. NCS-1 has since been shown to regulate and/or directly interact with many proteins including Cavs (P/Q, N, and L), TRPC1/5 channels, GPCRs, IP3R, and PI4 kinase type IIIβ. NCS-1 also affects neuronal outgrowth having roles in learning and memory affecting both short- and long-term synaptic plasticity. It is not known if NCS-1 affects neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity via its effect on PIP2 levels, and/or via a direct interaction with Ca2+ channels or their signaling complexes. This review gives a historical account of NCS-1 function, examining contributions from chromaffin cells, PC12 cells and other models, to describe how NCS-1’s regulation of Ca2+ channels allows it to exert its physiological effects.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9588-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Neuronal Calcium Sensor-1, NCS-1, Frequenin, Ca2+ channel, Chromaffin cells, PC12 cells, GPCR, Secretion, TRPC, Cavs, Exocytosis, PIP2, Ca2+ signaling

Background on NCS-1

Calmodulin is a ubiquitously expressed Ca2+-sensor involved in the regulation of many cellular processes. It is the best-studied prototypical example of the EF-hand family of Ca2+-sensor proteins and is the founding member of the Calmodulin superfamily of EF-hand Ca2+ sensing proteins. Other EF-hand-containing proteins have been identified that are highly expressed predominantly in neuronal cell types forming subfamilies within the Calmodulin superfamily. The neuronal Ca2+-sensor (NCS) subfamily (in which Calmodulin does not reside) includes proteins expressed only in the retina (e.g., Recoverin), and others expressed in neuronal and neuroendocrine cells such as the Neurocalcins and NCS-1 (otherwise known as Frequenin). The NCS proteins are 22 kDa, high-affinity Ca2+-binding proteins with >50% overall sequence identity to each another (their homology to Calmodulin is mainly in the EF-hands). The NCS protein family has many diverse roles in Ca2+ signaling in neurons and neuroendocrine cells (Burgoyne and Weiss 2001). The functional roles of many members of the family are becoming clearer and there are interesting clues as to the function of Neuronal Calcium Sensor-1 (NCS-1) (Burgoyne 2007).

NCS-1 was first described as Frequenin in Drosophila, where it was demonstrated, in molecular genetic and other studies, to regulate synaptic neurotransmission. Overexpression of Frequenin in Drosophila, in the V7 mutant, was found to facilitate evoked neurotransmission at the neuromuscular junction (Pongs et al. 1993). It is now known that there are two versions of Frequenin in Drosophila, frq1 and frq2 (Dason et al. 2009). NCS-1 is myristoylated, and is found at the Golgi and plasma membrane (McFerran et al. 1999; O’Callaghan et al. 2002). Overexpression of NCS-1 results in enhancement of evoked exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells (McFerran et al. 1998). The enhancement of exocytosis due to overexpression of NCS-1 in PC12 cells was observed in intact cells following stimulation with the purinergic agonist ATP. In digitonin-permeabilized cells when exocytosis was directly stimulated by Ca2+, there was no increase above background levels suggesting that NCS-1 did not impact directly on the exocytotic machinery.

It is important to understand the regulation of Ca2+ channels by the NCS-1 and other Ca2+ sensors (Weiss and Burgoyne 2002), as it seems to be through this modulation that NCS-1 exerts its physiological effects (control of exocytosis, control of neuronal outgrowth, etc.). We first started in this area of research about 10 years ago, when NCS-1 was relatively unknown, although the importance of Ca2+ as a second messenger was well understood. We now know that there are many Ca2+ sensing proteins, with different affinities for Ca2+, which regulate various crucial cellular signaling responses by sensing changes in Ca2+ within the cell, and then passing the signal onto the next signaling protein. NCS-1 has been shown to mediate desensitization of the D2 Dopamine receptor, regulate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Cavs) and exocytosis. NCS-1 regulates the enzyme PI4 kinase IIIβ in both yeast (Hendricks et al. 1999; Burgoyne 2007) and mammalian cells (Haynes et al. 2005), which is important in regulating cellular phosphoinositide levels. NCS-1 is known to be involved in learning and memory as well as both short- and long-term synaptic plasticity (Gomez et al. 2001; Jo et al. 2008; Burgoyne 2007). It has also been implicated in schizophrenia, cognitive defects such as mental retardation, autism, and fear (Burgoyne 2007; Saab et al. 2009; Handley et al. 2010). The field is now entering a new phase as more groups work on the NCS proteins. We anticipate that, as researchers find more links between the NCS family and the regulation of ion channels and membrane receptors, and identify the physiological effects, they will continue to be a major target for future research.

NCS-1 Regulation of Ca2+ Channels First Discovered in Adrenal Chromaffin Cells

Studies have demonstrated that Calmodulin (CaM) and other EF-hand Ca2+-sensing proteins are involved in the modulation of Cav channels (Levitan 1999; Weiss and Burgoyne 2002). We demonstrated that NCS-1 plays an essential role in the tonic inhibition of P/Q channels in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells, specifically in the voltage-independent pathway. This pathway for autocrine inhibition requires exocytosis, and relies on the activity of a Src-like kinase (Weiss et al. 2000; Weiss and Burgoyne 2001). The P/Q-subtypes of Cavs are important for neuronal excitability because they help to mediate exocytosis (Aldea et al. 2002). Adrenal chromaffin cells are an extensively characterized model system for secretory cells (Burgoyne 1991). These cells, which are found in the adrenal medulla, are derived embryonically from the same precursor cells that give rise to sympathetic neurons. Chromaffin cells are used as neuronal cell models because they contain many of the same proteins that are involved in neuronal function, and share common mechanisms for regulated exocytosis (Morgan and Burgoyne 1997). It is likely that NCS-1 regulates P/Q-type channels in neurons, where it could act on related presynaptic GPCR autoreceptor pathways to modulate Ca2+ channel function and thereby neurotransmitter release. Adrenal chromaffin cells have been a widely used model to study the regulation and function of Cavs in secretion (Fox et al. 2008). A recent study has shown that there is differential regulation of endogenous Cav subtypes by CaM, and that this impacts on the ability of these channels to regulate neurotransmitter release in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells (Wykes et al. 2007). Perhaps, other Ca2+ sensors such as NCS-1 cover the “slack” in regulation. We were able to create a mutant form of NCS-1, where the third EF-hand has been inactivated, called NCS-1 (E120Q). NCS-1 (E120Q) was developed as a dominant negative (DN) inhibitor of cellular NCS-1 function to study its role in these chromaffin cells and neurons (Weiss et al. 2000). Recombinant NCS-1 (E120Q) protein showed an impaired Ca2+-dependent conformational change, but could still bind to cellular proteins. Transient expression of this mutant, but not wild-type NCS-1, in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells increased non-L-type Ca2+ channel currents. Cells expressing NCS-1 (E120Q) no longer responded effectively to the removal of autocrine purinergic/opioid inhibition of Ca2+ currents, but still showed voltage-dependent facilitation (Weiss et al. 2000). The results provided insight into a novel function for NCS-1, in which it acts on a receptor-mediated feedback pathway controlling non-L-type Ca2+ channel function in chromaffin cells. The data supports the existence of both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent pathways for the regulation of Ca2+ channels in chromaffin cells (Beech et al. 1991; Beech and Bernheim 1992; Garcia et al. 2006). NCS-1 appears to specifically act in the voltage-independent pathway. Further studies (Weiss and Burgoyne 2001) revealed that this voltage-independent inhibition requires both NCS-1 and a Src-like kinase, since two functionally and structurally distinct Src-kinase inhibitors (PP1 (4-amino-5-(4-methylphenyl)-7-(-t-buttyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine) and Src inhibitory peptide) cause facilitation of Ca2+ channel currents and PP1 had no effect on the NCS-1 (E120Q) overexpressing cells. It was also demonstrated that P/Q-type Ca2+ channels are involved, and that they are phosphorylated on tyrosine residues. This suggests that tyrosine phosphorylation by a Src-like kinase might be a mechanism for the inhibition of P/Q-type channels in chromaffin cells. It is therefore clear that Frequenin/NCS-1 has an important regulatory role in the steps leading to Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of synaptic vesicles and dense core granules neuroendocrine cells via its effects on Cav Ca2+ channel currents. NCS-1 may play a similar role in neurons, where it could act on related presynaptic autoreceptor pathways to modulate Ca2+ channel function and thereby neurotransmitter release.

What is Known About the Effects of NCS-1 on Cav Channels and Secretion?

Effects on Cav Channels

One of the most important components that enable neurons to undergo synaptic transmission is the voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (Cav). Cav channel complexes have 3–4 subunits made up of pore-forming α subunits, and auxiliary subunits including Cavβ (Catterall 2000; Catterall et al. 2003). They are subject to various forms of modulation, including inhibition via G-Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) signaling pathways (Dolphin 2003a). Cavβs can compete with G-protein binding to the Cav α-subunits and have many other regulatory roles (Dolphin 2003b, 2009).

In addition to the work from our lab described above, other studies have implicated NCS-1 in the regulation of various types of Ca2+ channels. NCS-1 has been shown to increase the current amplitude of N-type channels at the frog neuromuscular junction in a pathway that requires GDNF (Wang et al. 2001). NCS-1 has been proposed to alter secretion (exocytosis) in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells via a mechanism involving PI4 kinase (Pan et al. 2002), and to increase activity-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type channels in the Calyx of held (Tsujimoto et al. 2002). Inhibition of P/Q channels by NCS-1 has also been shown to be Cavβ subunit-specific (Rousset et al. 2003). Work over the past 10 years on NCS-1 regulation of Ca2+ channels is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarization of publications describing NCS-1 regulation of Ca2+ channels over the past 10 years

| Channel type | Effect on current | Functional effect | Cell background | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P/Q-type | ⇓ Current in GPCR pathway | Autocrine/paracrine Feedback inhibition loop-ATP and opioids and SRC-like kinase | Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells | Weiss et al. (2000) and Weiss and Burgoyne (2001) |

| N-type | ⇑ Current in GDNF pathway | ⇑ of both spontaneous and evoked secretion | Xenopus neuromuscular synapse | Wang et al. (2001) |

| P/Q-type | ⇑ Current | Rapid Ca2+-dependent facilitation | Calyx of held | Tsujimoto et al. (2002) |

| Capacitative Ca2+ entry? | ⇑ Current, no effect on Cavs? | Differential effects of NCS-1 on secretion with depolarization induced get rundown of exocytosis but enhancement via PIP2 enhancement pathways? | Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells and rat PC12 cells | Pan et al. (2002) and Koizumi et al. (2002) |

| L, N, P/Q-type | ⇓ Current | ⇓ of all Cav currents but effect on Cav2.1 was Cavβ subunit dependent | Xenopus oocytes | Rousset et al. (2003) |

| N-type | ⇓ Current via PIP2 and IP3 signaling pathways? | DNNCS-1 decreased current via Bradykinin (BK) receptors, overexpression of NCS-1 reduces BK inhibition | Rat superior cervical ganglion (SCG), sympathetic neurons, Xenopus oocytes | Gamper et al. (2004), Winks et al. (2005), and Zaika et al. (2007) |

| TRPC5 | ⇑ Current by acting as the Ca2+ sensor for TRPC5 | DNNCS-1 increased neurite length but had no effect on neurite no., NCS-1 binds directly to TRPC5 but may have effects via PIP2? | Rat PC12 cells that have endogenous TRPC4/5 channels but no detectable Cavs. | Hui et al. (2006) |

| N-type | ⇓ Current dependent on IL1RAPL1 | ⇑ secretion correlated with reduced NGF induced neurite elongation | Rat PC12 cells with low level of detectable Cavs | Gambino et al. (2007) |

| N-type | ⇓ Current of growth cones but not soma | NCS-1 C-terminal peptide reduced N-type currents increasing rate of neurite branching but not outgrowth | Lymnaea stagnalis neurons | Hui et al. (2007) and Hui and Feng (2008) |

| α1 voltage-gated Ca2+ -channel subunit (cacophony null mutant) | ⇓ Current in frq1/frq2 null mutants | Functional interaction with α1 channel subunit that is not dependent on PI4 Kβ and inhibits secretion and enhanced nerve terminal growth | Drosophila | Dason et al. (2009) |

Does NCS-1 Regulate Secretion Via Cavs?

There are still many unanswered questions. For example, why are there different effects on P/Q channels in different primary cell types (i.e., Calyx of held vs. bovine adrenal chromaffin cells) (Weiss and Burgoyne 2002)? How exactly does NCS-1 exert its effect on the modulation of N- and P/Q-type channels? How does NCS-1 affect exocytosis and neurotransmitter release? Does the effect on exocytosis involve PI4 kinaseIIIβ, or does it involve the regulation of Ca2+ channels as well? Does NCS-1 affect membrane trafficking of different protein types, including ion channels, depending on how much Ca2+ it senses? The fact that there are multiple effects of NCS-1 on different Ca2+ channels could be due to the particular proteins expressed in a specific cell type (e.g., Cavβ subunits, GPCR receptors and other signaling molecules).

NCS-1 Regulation of Ca2+ Channels and Neuronal Outgrowth

Ca2+ and Neuronal Outgrowth

The neuronal growth cone is the expansion at the end of developing axons and dendrites. They protrude “finger-like” structures <1 μm in diameter and up to 10 μm in length called filopodia, connected to the processes by “palm-like” structures called lamellipodia. Neurite outgrowth and axon pathfinding are initiated by active growth cone extension and retraction (Henley and Poo 2004). Changes in growth cone morphology are important not only during development but also in mature nerve cells, regulating the synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory (Petersen and Cancela 2000). Intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) has been reported to play a critical role in the regulation of neurite outgrowth (Konur and Ghosh 2005). A theory formed in 1993, termed the “Ca2+ set-point” hypothesis, states that the growth cone is motile only when an optimal range of [Ca2+]i is present. Above or below this range, neurite growth stops (Fields et al. 1993).

Role of NCS-1 in Neuronal Morphology and Outgrowth

NCS-1 was first reported as a regulator for neuronal morphology when overexpression in Drosophila led to both a reduced number and length of branches, and a reduced number of synaptic boutons in motor nerve terminals (Angaut-Petit et al. 1998). A similar result to this was obtained when using GFP-tagged NCS-1 in differentiated NG108-15 cells, accompanied with enhanced functional synapse formation (Chen et al. 2001). These findings triggered a search for the role of NCS-1 in neurite modulation, when its regulatory effect was observed on another neurite outgrowth regulator, TRPC5 channels (Greka et al. 2003; Bezzerides et al. 2004). Using a pore-blocking mutant of TRPC5 to abolish Ca2+ entry (DN TRPC5), and the NCS-1 (E120Q) (DN NCS-1) to reduce Ca2+ sensing ability, we suggested a common pathway with these two proteins in controlling neurite length without affecting neurite numbers through direct interaction in PC12 cells (Hui et al. 2006). NCS-1 appears to act as the Ca2+ sensor for TRPC5 channels to allow TRPC5 channels to respond to changes in Ca2+ transients and in turn control the Ca2+ level of entering the neuronal growth cone. We propose that NCS-1 acts as a “permission switch” that enables full TRPC5 channel-mediated responses to physiological and pathological modulators to control neurite outgrowth.

A different mechanism was suggested in PC12 cells in which Interleukin-1 Receptor Accessory Protein-like 1 (IL1RAPL1) recruits NCS-1 to the plasma membrane under resting conditions and stimulates its negative regulatory activity on N-type Cavs when the concentration of NCS-1 is high. In this study, silencing of NCS-1 by small interfering RNA (siRNA)s increased neurite outgrowth only in IL1RAPL1 stably expressing cells (Gambino et al. 2007). Nonetheless, the contribution of regulating neurite outgrowth by NCS-1’s inhibitory effect on N-type Cav is ambiguous, as chronic inhibition of N-type Cav blocker ω-conotoxin failed to prevent neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells by NGF (Bouron et al. 1999), indicating that other Ca2+ channels or sources may also be involved. These results provide a platform for the idea that another Ca2+ source, such as the TRPC5 channel, is the downstream target for the IL1RAPL1/NCS-1 interaction in regulating neurite outgrowth. The discrepancy of whether IL1RAPL1 is required in neurite elongation in response to NCS-1 manipulation may be explained by PC12 cell clonal differences. In Gambino et al., study they were able to detect very small Cav currents. In contrast, results from our study using RT-PCR and immunoprecipitations indicated the presence of TRPC5 channels, although we could not find any detectable Cav currents in the PC12 cell clone used (Hui et al. 2006). We observed multiple neurites with limited or no branching from single differentiated PC12 cell bodies.

NCS-1 Regulation of Neurite Elongation and Branching

In cultured primary neurons from Lymnaea stagnalis, NCS-1 was shown to differentially regulate neurite elongation and neurite branching through separate structural domains (Hui et al. 2007). Both the number of branches and rate of neuronal outgrowth were significantly increased when NCS-1 was knocked down ~30% by specific homologous double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) treatment. A C-terminal NCS-1 peptide (CTN) with abolished EF-4 hand Ca2+ binding increased the rate of neurite branching, leaving the neurite outgrowth intact. In a subsequent study using the CTN peptide again, the same group found that NCS-1 differentially regulates Ca2+ currents in the growth cone versus the soma (Hui and Feng 2008). The authors conclude that two separate NCS-1 structural domains (C- vs. N-terminus) have differential effects on neuronal outgrowth and branching. The use of the NCS-1 (E120Q) DN mutant in our studies (Hui et al. 2006) may create a scenario in which a partially Ca2+ bound NCS-1 can still physically translocate to the growth cone, sending out the signals of low Ca2+ concentration to its interaction partners, and is therefore likely to differ from the RNAi (RNA interference) method in which NCS-1 function is lost or the use of the CTN peptide.

NCS-1’s Enrichment in the Neuronal Growth Cone

NCS-1 has been reported to increase IP3R channel activity in both a Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent manner (Schlecker et al. 2006). A recent study provides further evidence for the role of NCS-1 in growth cone morphology. This report showed that release from Ca2+ stores via the IP3R is crucial for the localization of NCS-1 in the growth cone (Iketani et al. 2009). This data is in agreement with our data that endogenous NCS-1 is localized in the central growth cone (lamellipodia) (Supplemental Figure 1a). A chromophore-assisted laser inactivation (CALI) technique was used to induce acute ablation of NCS-1, and this resulted in the inhibition of neurite outgrowth. As such, a role for NCS-1 to promote neurite outgrowth via microtubule assembly was suggested. These findings are in contrast to previous studies (Hui et al. 2006, 2007) where NCS-1 (E120Q) overexpression or ~30% NCS-1 RNA knockdown resulted in neurite elongation. With the CALI method, however, a more complete ablation of NCS-1 and its function would be achieved, which may explain why neurite retraction instead of neurite elongation was observed in this study. NCS-1 has been shown to be important for synapse formation (Chen et al. 2001), and it could be that the NCS-1 protein is needed to maintain neuronal growth cones, also explaining why its removal causes their retraction. Our data from both transfected and differentiated PC12 cells demonstrates an enrichment of NCS-1 in growth cone filopodia and lamellipodia regions when NCS-1 (E120Q) and DNTRPC5 are both co-overexpressed (Supplemental Figure 1b). During neurite elongation, an appropriate Ca2+ concentration may be maintained through NCS-1’s regulation of TRPC5 channels possibly in the filopodia and lamellipodia region.

We have previously demonstrated a direct interaction between NCS-1 and TRPC5 (Hui et al. 2006). In our data, only the NCS-1 (E120Q) DN mutant was observed to be enriched in the filopodia and lamellipodia regions of PC12 cells when overexpressed with DNTRPC5 (Supplemental Figure 1b, 2a). It is apparently not an overexpression effect, as neither the overexpressed wild-type NCS-1 together with DNTRPC5 nor the DN NCS-1 (E120Q) with wild-type TRPC5 combination, yielded the same enrichment of NCS-1 in these neurite regions (Supplemental Figure 2a). To explain this phenomenon, we hypothesize that Ca2+ entry through TRPC5 channels is required when inhibition of neurite elongation is needed. When enhanced neurite outgrowth occurs due to DNTRPC5 overexpression, more endogenously expressed TRPC5 channels are needed to insert into the growth cone, including the filopodia and lamellipodia. It is likely that the physically bound NCS-1 (E120Q) was enriched in the same region where it helps TRPC5 channels to translocate into the filopodia (Bezzerides et al. 2004). In the experimental groups where wild-type NCS-1 with DNTRPC5 or NCS-1 (E120Q) with TRPC5 is co-expressed, the neurite elongation effect was rescued and, therefore, no translocation of the NCS-1/TRPC5 complex occurred. Similar results were obtained in transfected chromaffin cells differentiated by NGF or K+ depolarization (Supplemental Figure 1a, b; some data not shown).

NCS-1’s Signaling Effect on Growth Cone Morphology

Overall Ca2+ levels in neurons are regulated by influx through Ca2+ channels and release from intracellular Ca2+ stores. Influx through Cavs has been reported to have both positive and negative effects on growth cone morphology (Yao et al. 2005). Human Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM) promotes neurite outgrowth via activation of a common CaM-specific second messenger pathway in rat cerebellar neurons, depending on Ca2+ levels (Williams et al. 1992). This attractive response is converted to repulsion when neurons are treated with an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker (Hong et al. 2000). In contrast, when neonatal rat locus coeruleus neurons encounter myelin extracts from CNS, the intracellular free Ca2+ concentration increases through N-type Ca2+ channels, followed by collapse of growth cones (Moorman and Hume 1993). These different phenomena can be explained by the pattern of Ca2+ transients, which differ in time and space in response to various stimuli, and it is the culmination of these signals that affect the final response (Bolsover 2005). IL1RAPL1 could be acting upstream, maintaining the balance of whether to differentiate (a number of PC12 cells stably expressing IL1RAPL1 failed to differentiate in response to NGF, and the ones that did seemed to have few neurites) (Gambino et al. 2007). No clear evidence indicates that the N-type is the only Ca2+ channel that is involved in the IL1RAPL1/NCS-1 neurite outgrowth pathway. We were only able to detect TRPC5 in PC12 cells by RT-PCR and immunoprecipitations, indicating that very low levels of TRPC5 channels are required in the outgrowth processes, yet endogenous NCS-1 expression levels are very high. It is therefore possible that NCS-1 has multiple partners in regulating neurite outgrowth. N-type, TRPC5 channels, and the IP3R may crosstalk in this signaling pathway with NCS-1 to regulate neuronal outgrowth. With IP3R activation, NCS-1 would sense release from Ca2+ stores specifically to facilitate microtubule assembly in the central growth cone. In basal conditions, when inhibition of neurite outgrowth is desired, the TRPC5 and NCS-1 partners can insert into the growth cone tip, filopodia, and lamellipodia regions to induce Ca2+ influx and exceed the maximum elongation Ca2+ window concentration to inhibit neuronal outgrowth.

In a very recent article (Yip et al. 2010), lentivector-induced NCS-1 was overexpressed in both cultured and in vivo injured adult rat spinal cord neurons. Unless the PI3K/Akt pathway was inhibited, NCS-1 overexpression appeared to increase neurite outgrowth and sprouting. This seems to be in contrast to previous work in PC12 cells (Hui et al. 2006, 2007). However in the PC12 cells studies, the PI3K/Akt pathway may not have been active and some of the signaling components in various PC12 cell lines that are present in rat primary cortical neurons may not be present in the particular PC12 cell clone lines used (e.g., no Cavs in the Hui et al. 2006 PC12 cell clone line used). Nevertheless, NCS-1 has been shown to reduce both neuronal outgrowth and branching in Drosophila (Angaut-Petit et al. 1998) and in snail neurons (Hui et al. 2007; Hui and Feng 2008). Therefore, data demonstrating NCS-1’s ability to retard neuronal outgrowth is not restricted to the PC12 cell system. NCS-1 has been shown to signal in the PI3K/Akt pathway helping to increase neuronal survival (Nakamura et al. 2006) and activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway has been reported to control neurite branching in the clone of PC12 cells used in another study (Higuchi et al. 2003). Thus, it is possible that NCS-1 may have different effects on neurite outgrowth and branching depending on which Ca2+ channels it regulates and whether the PI3K/Akt pathway is active as well. NCS-1 could either inhibit or enhance neurite outgrowth and/or branching depending on its interacting partners and the signaling pathways that are active at the time and in a particular cell type.

Dual Effects of NCS-1 on Both Cav Channels and Secretion (Exocytosis)

NCS-1 Effects on Exocytosis

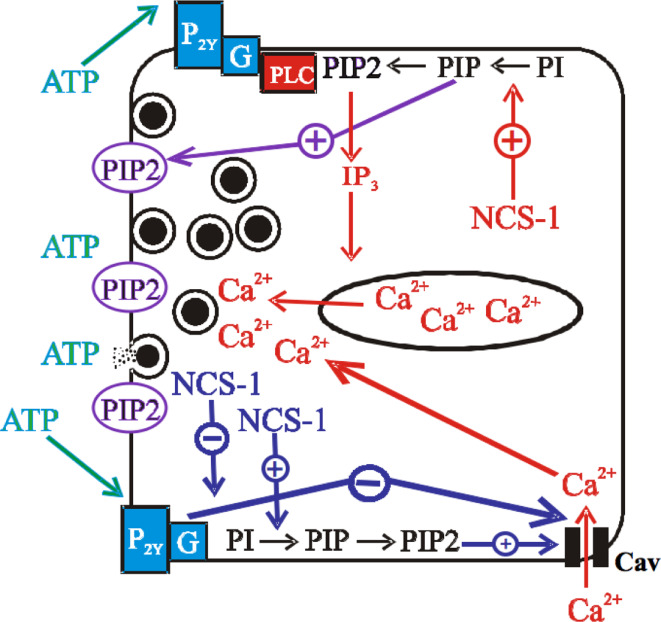

Using reporter growth hormone (GH) assays in transfected PC12 cells (McFerran et al. 1998), the effect of NCS-1 overexpression was examined using various stimuli to evoke secretion (Supplemental Figure 2b). In cells stimulated with ATP to activate purinergic receptors, NCS-1 significantly enhanced GH release. However, when NCS-1 was stimulated with high K+ for 15 min to evoke release via depolarization (which activates Cavs), NCS-1 overexpression significantly inhibited release. When both receptors and channels were bypassed by permeabilizing cells with digitonin and adding Ca2+ directly to evoke release, NCS-1 had no effect on secretion, indicating that the effects of NCS-1 are on signaling pathways rather than acting directly on the secretory machinery. This data provides evidence for a model in which NCS-1 can have dual effects on the regulation of Cavs and secretion (Fig. 1). This would allow us to propose that NCS-1 does not always enhance exocytosis. Instead, NCS-1 acts as a mediator for controlling PIP2 levels and regulating Cav channel function. PIP2 is essential for exocytosis being important for vesicle fusion and motility (Martin 2005). NCS-1 would exert its effect to control the level of exocytosis so that there is neither too much nor too little secretion to achieve a fine balance of neurotransmission. This fine balance is crucial to the function of both neurons and neuroendocrine cells.

Fig. 1.

Model of NCS-1 dual regulation of Cavs and secretion where NCS-1 acts as a mediator of neurotransmission. The lines depict NCS-1’s effect on secretion and Cav channels. An arrow with a + represents an effect to increase activity while one with a − depicts a decrease in activity. NCS-1 can enhance secretion via its activation of PI4 kinaseIIIβ and the subsequent increase in PIP2 levels leading to an increase in IP3 mediated internal Ca2+ store release. This increase in Ca2+ levels will increase vesicle motility to drive vesicles to fuse with the plasma membrane to release their contents. In addition, plasma membrane pools of PIP2 itself promote vesicle fusion and motility. PIP2 can also stabilize Cav channels (N-type) function and this can be enhanced via NCS-1 due to its activation of PI4 kinaseIIIβ and the subsequent rise in PIP2 levels. NCS-1 can also inhibit Cavs (P/Q-type) via its signaling in a purinergic GPCR inhibition pathway. The exact mechanism of how NCS-1 inhibits P/Q-type Cavs is unknown but data indicates that a PTX insensitive G-protein and a Src-like kinase are involved (Weiss and Burgoyne 2001)

Data from the Fox lab, where they examined NCS-1’s effect on secretion and Cavs in chromaffin cells, also demonstrate differential effects of NCS-1 on secretion when using depolarization versus histamine to evoke secretion (Pan et al. 2002). They also observed a rundown of secretion with the former, and an enhancement with the latter. However, they did not note an inhibition of Cavs in their experimental conditions. It is possible that their use of short depolarization pulses in their study, rather than the experimental conditions used for the PC12 cells in our study (15-min treatment and secretion period with high K+ (55 mM)) (Supplemental Figure 2b), could explain the differences in the findings. The longer depolarization period with high K+ would allow the build up of released ATP, creating extensive feedback inhibition of Cav channels. In these conditions, the effect of NCS-1 to inhibit P/Q channels could be enough to reduce secretion (Fig. 1).

A Clue From Studies in Drosophila

We know that NCS-1, in different cell signaling backgrounds, can either inhibit or facilitate Cavs (mainly P/Q and N). How then is NCS-1’s regulation of Cavs linked to its regulation of both secretion and neuronal outgrowth? NCS-1 is well known to stimulate the activity of PI4 kinaseIIIβ, and it has been suggested that it is through this activity and its effects on phosphoinositides that it enhances exocytosis (Hilfiker 2003). Interestingly, we started out with understanding the function of Frequenin/NCS-1 in Drosophila, and although we have learned additional important information from mammalian systems, now we have made a full circle back to Drosophila for clarification. A recent genetic study in Drosophila has shown that the physiological effects of knock-out of the Frequenins cannot be explained by interaction with the fly gene for the orthologue of PI4 kinaseIIIβ (Dason et al. 2009). Importantly, this study instead suggests that the role of Frequenin in neurotransmitter release and nerve terminal growth in Drosophila can be explained entirely by interaction with the cacophony gene, which encodes the Drosophila orthologue of the mammalian P/Q channel α-subunit. This leads one to speculate that perhaps in mammals a more complex signaling system evolved, allowing NCS-1 to regulate neurotransmission and exocytosis by a variety of signaling pathways that may be cell-type specific.

Conclusions, More Questions, and Future Directions

In chromaffin and PC12 cells, NCS-1 can enhance secretion via its activation of PI4 kinaseIIIβ with the subsequent increase in PIP2 levels. PIP2 has been shown to be an important requirement for exocytosis (Hay et al. 1995; Martin et al. 1997). There is evidence that NCS-1 can generally increase secretion via its increase of PI4 kinaseIIIβ activity and the subsequent build up of PIP2 levels (Koizumi et al. 2002; de Barry et al. 2006). However, when there is a build up of secreted components such as ATP, NCS-1 provides a feedback mechanism to control secretion via its inhibition of P/Q channels (Supplemental Figure 2b, Fig. 1). NCS-1 inhibits GRK2, which phosphorylates GPCRs and marks them for internalization via a desensitization pathway. In this way, NCS-1 could keep GPCRs at the plasma membrane so that they can continue to be activated in the presence of ligand binding. This has been demonstrated specifically for D2 receptors (Kabbani et al. 2002), but this could be one general mechanism by which NCS-1 inhibits Cavs via GPCR inhibitory pathways, as this would allow more GPCRs to stay at the cell surface to be activated to inhibit Cavs such as P/Q channels. The situation may differ, though, in other cell types and different neurons as NCS-1 has variable effects on N- versus P/Q-type channels. PIP2 has very recently been shown to be especially important for supporting N-type channel function, as depletion of plasma membrane PIP2 reduces N-type currents by as much as 55%, while other Cav currents are affected in this way by only ~29–35% (Suh et al. 2010). It is therefore possible that NCS-1 enhances N-type channels at least in part by its ability to increase PIP2 levels. In addition, since NCS-1 can signal in the PI3K/Akt pathway (Nakamura et al. 2006) and PI3 Kinase has been reported to promote N-type channel trafficking to the plasma membrane (Viard et al. 2004), NCS-1 may also increase the number of N-type channel pore-forming subunits (Cav2.2) in the membrane. This could explain the cellular mechanism of how NCS-1 enhances N-type currents (Wang et al. 2001).

In summary, NCS-1 acts a mediator to enhance secretion via its ability to increase PIP2 levels, which directly enhance secretion and stabilize Cav function in the plasma membrane. However, NCS-1 can put a clamp on secretion if PIP2 levels run down or when NCS-1 inhibits P/Q channels (Fig. 1) via inhibitory autoreceptors such as P2Y12 or D2 dopamine receptors—most likely via its inhibition of GRK2 (Kabbani et al. 2002).

NCS-1 and Control of PIP2 Levels

In addition to being a requirement for exocytosis (Martin 2005), PIP2 is reported to stabilize Cavs and regulate TRP channels (Rohacs 2007; Suh and Hille 2008). PIP2 has been suggested to regulate TRPC5 channels in a complex fashion (Trebak et al. 2009). NCS-1 increases PIP2 levels via its activation of PI4 kinaseIIIβ, and PIP2 is thought to be involved in TRPC5 translocation to growth cones (Bezzerides et al. 2004). PIP2 is also known to stabilize N-type channels and prevent rundown in a voltage-independent slow GPCR signaling pathway (via Gq/11) (Michailidis et al. 2007). In fact, NCS-1 has been implicated in pathways that differentially modulate N-type channels in GPCR activation and PIP2 signaling pathways (Gamper et al. 2004; Zaika et al. 2007). It seems we also need to take into account NCS-1’s variable effects on different Ca2+ channels, secretion, and neuronal outgrowth also in the context of its regulation of PIP2 levels, as Cavs appear to produce larger currents when plasma membrane PIP2 levels are maintained (Suh et al. 2010), and depletion of PIP2 would be expected to inhibit exocytosis as PIP2 membrane pools are essential for vesicle fusion (James et al. 2008; Milosevic et al. 2005).

Unanswered Questions

There are a number of questions that remain to be answered. Why does NCS-1 have different effects on the very same Ca2+ channel in different cells types (e.g., different effects of P/Q in chromaffin cells vs. the Caylx of held)? What is the link between NCS-1, PIP2, Cavs, and TRPC channels? Is there crosstalk between the Cavs and TRPC channel signaling pathways via NCS-1 and PIP2? Also, what is the role of Cavβ subunits in NCS-1 regulation of Ca2+ channels? NCS-1 also has varied reported effects on the regulation of neuronal outgrowth and secretion. Could this be connected to differences in the regulation of PIP2 levels via NCS-1? In addition, it may be possible that it is too difficult to compare different studies where some use NCS-1 overexpression and some experiments relied on data from knock-down or knock-outs of NCS-1/frequenin (as in Drosophila). There is a danger of relying entirely on overexpression data as this could have unpredicted effects on other Ca2+ signaling pathways. This may in part explain some of the variable effects of NCS-1 reported. An NCS-1 mouse knock-out is not currently available but would be an excellent tool to help dissect its many signaling effects (control of exocytosis, neuronal outgrowth, etc.) and the ultimate effect on the physiology of the animal.

Clearly, much further work will be needed to determine the exact functional roles of NCS-1 and the signaling pathways involved in its regulation of Ca2+ channels, secretion (exocytosis), and neuronal outgrowth in different cell signaling backgrounds. However, it seems that we should stop thinking of NCS-1 as inhibiting or enhancing a cellular effect (e.g., exocytosis). Perhaps, its role really is to be a mediator based on the level of [Ca2+]i and the location of the Ca2+ transients it senses. In this context, NCS-1 modulates Ca2+ channels, which in turn control exocytosis and this helps it to regulate neuronal outgrowth.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(a) Endogenous NCS-1 Staining in K+ Differentiated Chromaffin Cells. Left panel transmitted light image of living differentiated bovine adrenal chromaffin cells by K+ (55 mM) depolarization for 48 h in the presence of FBS. Bovine chromaffin cells were electroporated with DN TRPC5 plasmid and incubated for 48 h. 55 mM K+ was added into the growth media to differentiate them for 48 h prior to co-immunostaining. Cells were co-stained with anti-DBH (Dopamine β-Hydroxlase) to label chromaffin cell exocytotic vesicles (TRITC, A), anti-NCS-1 (FITC, B) and phalloidin (Alexa Flour® 350, C). D is the merged image of A, B and C, in which both NCS-1 and DBH are enriched in the cell body and the growth cone areas. E, F and G are enlarged image of growth cones from the merged areas in boxes from picture D. Arrows point to the neurite filopodia tips, which are stained with phalloidin labeling the polymerized actin. Note NCS-1 staining is not present in the filopodia tips. (b) DN NCS-1 in NGF Differentiated Double Mutant Expressing Chromaffin Cells. Left panel living differentiated bovine adrenal chromaffin cells differentiated by NGF (100 ng/ml) for 10 days in the absence of FBS. Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells were electroporated with DN NCS-1 and DN TRPC5 plasmids and incubated for 48 h. 100 ng/ml NGF was used in a FBS free growth media to differentiate them for 10 days prior to co-immunostaining. Cells were co-stained with anti-DBH (TRITC, A), anti-NCS-1 (FITC, B) and phalloidin (C). D is the merged image of A, B and C, in which both NCS-1 and DBH are enriched in the cell body and the growth cone areas. E, F and G are enlarged images of growth cones from the merged areas in boxes from picture D. Arrows point to filopodia tips to show lack of phalloidin staining (compare to (a)) and enrichment in NCS-1 and DBH staining overlay. H. Hui and J.L. Weiss, data in preparation. (TIFF 2380 kb)

(a) Quantification of NCS-1 Enrichment in Tips of Differentiated PC12 Cell Filopodia in DN/DN TRPC5/NCS-1 combination. PC12 cells transfected with cDNA constructs as indicated and fluorescence intensity of NCS-1 and tubulin staining was measured from digital photos using ImageJ software. Mean ± SEM **p < 0.001 shows significant differences via a students t-test of increased ratio value compared to the other cell groups (n = 25 cells/condition). H. Hui and J.L. Weiss, data in preparation. (b) Differential effects of NCS-1 over-expression on reporter growth hormone (GH) release from PC12. Cells were transfected with control or NCS-1 plasmid along with a GH encoding plasmid. After 3 days the cells were washed and challenged with (A) 300 mM ATP or (B) 55 mM KCl. Other cells (C) were permeabilized for 6 min by incubation in 20 mM digitonin and then challenged without (basal) or with 10 mM free Ca2+. After incubation for 15 min cellular GH and GH present in the medium were assayed and released GH expressed as a percentage of total GH. The extent of release was then normalized to the mean value of release for control stimulated cells. The data are shown as mean + SEM (n = 6). M.E. Graham and R.D. Burgoyne, data in preparation. (TIFF 2380 kb)

Footnotes

A commentary to this article can be found at doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9611-z.

References

- Aldea M, Jun K, Shin HS, Andres-Mateos E, Solis-Garrido LM, Montiel C, Garcia AG, Albillos A (2002) A perforated patch-clamp study of calcium currents and exocytosis in chromaffin cells of wild-type and α1A knockout mice. J Neurochem 81:911–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angaut-Petit D, Toth P, Rogero O, Faille L, Tejedor FJ, Ferrus A (1998) Enhanced neurotransmitter release is associated with reduction of neuronal branching in a Drosophila mutant overexpressing Frequenin. Eur J Neurosci 10:423–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ, Bernheim L (1992) Pertussis toxin and voltage dependence distinguish multiple pathways modulating calcium channels of rat sympathetic neurons. Neuron 8:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ, Bernheim L, Mathie A, Hille B (1991) Intracellular Ca2+ buffers disrupt muscarinic receptor suppression of Ca2+ current and M current in rat sympathetic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:652–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzerides VJ, Ramsey IS, Kotecha S, Greka A, Clapham DE (2004) Rapid vesicular translocation and insertion of TRP channels. Nat Cell Biol 6(8):709–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolsover SR (2005) Calcium signalling in growth cone migration. Cell Calcium 37(5):395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouron A, Becker C, Porzig H (1999) Functional expression of voltage-gated Na + and Ca2 + channels during neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells with nerve growth factor or forskolin. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 359(5):370–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD (1991) Control of exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1071:174–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD (2007) Neuronal calcium sensor proteins: generating diversity in neuronal Ca2 + signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci 8(3):182–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Weiss JL (2001) The neuronal calcium sensor family of Ca2+-binding proteins. Biochem J 353:1–12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA (2000) Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol 16:521–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Perez-Reyes E, Snutch TP, Striessnig J, International Union of Pharmacology (2003) International Union of Pharmacology. XL. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev 55(4):579–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhong ZG, Yokoyama S, Bark C, Meister B, Berggren PO, Roder J, Higashida H, Jeromin A (2001) Overexpression of rat neuronal calcium sensor-1 in rodent NG108–15 cells enhances synapse formation and transmission. J Physiol 532(3):649–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dason JS, Romero-Pozuelo J, Marin L, Iyengar BG, Klose MK, Ferrús A, Atwood HL (2009) Frequenin/NCS-1 and the Ca2+-channel 1-subunit co-regulate synaptic transmission and nerve-terminal growth. J Cell Sci 122:4109–4121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Barry J, Janoshazi A, Dupont JL, Procksch O, Chasserot-Golaz S, Jeromin A, Vitale N (2006) Functional implication of neuronal calcium sensor-1 and PI4 kinase-β interaction in regulated exocytosis of PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 281:18098–18111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC (2003a) G protein modulation of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev 55(4):607–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC (2003b) Beta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr 35(6):599–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC (2009) Calcium channel diversity: multiple roles of calcium channel subunits. Curr Opin Neurobiol 19(3):237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields R, Guthrie PB, Russell JT, Kater SB, Malhotra BS, Nelson PG (1993) Accommodation of mouse DRG growth cones to electrically induced collapse: kinetic analysis of calcium transients and set-point theory. J Neurobiol 24:1080–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AP, Cahill AL, Currie KPM, Grabner C, Harkins AB, Herring B, Hurley JH, Xie Z (2008) N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in adrenal chromaffin cells. Acta Physiol 192(2):247–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambino F, Pavlowsky A, Begle A, Dupont JL, Bahi N, Courjaret R, Gardette R, Hadjkacem H, Skala H, Poulain B, Chelly J, Vitale N, Humeau Y (2007) IL1-receptor accessory protein-like 1 (IL1RAPL1), a protein involved in cognitive functions, regulates N-type Ca2+-channel and neurite elongation. PNAS 104(21):9063–9068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper NRV, Yamada Y, Yang J, Shapiro MS (2004) Phosphotidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate signals underlie receptor-specific Gq/11-mediated modulation of N-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci 24(48):10980–10992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AG, García-De-Diego AM, Gandía L, Borges R, García-Sancho J (2006) Calcium signaling and exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Physiol Rev 86(4):1093–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M, De Castro E, Guarin E, Sasakura H, Kuhara A, Mori I, Bartfai T, Bargmann CI, Nef P (2001) Ca2+ signaling via the neuronal calcium sensor-1 regulates associative learning, memory in C. elegans. Neuron 30(1):241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greka A, Navarro B, Oancea E, Duggan A, Clapham DE (2003) TRPC5 is a regulator of hippocampal neurite length and growth cone morphology. Nat Neurosci 6(8):837–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley MTW, Lian LY, Haynes LP, Burgoyne RD (2010) Structural and Functional Deficits in a Neuronal Calcium Sensor-1 Mutant Identified in a Case of Autistic Spectrum Disorder. PLoS One 5(5):e10534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Fisette PL, Jenkins GH, Anderson RA, Fukami K, Takenawa T, Martin TFJ (1995) ATP-dependent inositide phosphorylation required for Ca2+-activated secretion. Nature 374:173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes LP, Thomas GM, Burgoyne RD (2005) Interaction of neuronal calcium sensor-1 and ADP-ribosylation factor 1 allows bidirectional control of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase beta and trans-Golgi network-plasma membrane traffic. J Biol Chem 280(7):6047–6054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks KB, Wang BQ, Schnieders EA, Thorner J (1999) Yeast homologue of neuronal Frequenin is a regulator of phosphatidylinositol-4-OH kinase. Nat Cell Biol 1(4):234–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley J, Poo M-m (2004) Guiding neuronal growth cones using Ca2+ signals. Trends Cell Biol 14(6):320–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M, Onishi K, Masuyama M, Gotoh Y (2003) The phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathway suppresses neurite branch formation in NGF-treated PC12 cells. Genes Cells 8(8):657–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilfiker S (2003) Neuronal calcium sensor-1: a multifunctional regulator of secretion. Biochem Soc Trans 31(Pt 4):828–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K, Nishiyama M, Henley J, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo M (2000) Calcium signalling in the guidance of nerve growth by netrin-1. Nature 403(6765):93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui K, Feng ZP (2008) NCS-1 differentially regulates growth cone and somata calcium channels in Lymnaea neurons. Eur J Neurosci 27(3):631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui H, McHugh D, Hannan M, Zeng F, Xu SZ, Khan SU, Levenson R, Beech DJ, Weiss JL (2006) Calcium-sensing mechanism in TRPC5 channels contributing to retardation of neurite outgrowth. J Physiol 572(Pt 1):165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui K, Fei GH, Saab BJ, Su J, Roder JC, Feng ZP (2007) Neuronal calcium sensor-1 modulation of optimal calcium level for neurite outgrowth. Development 134(24):4479–4489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iketani M, Imaizumi C, Nakamura F, Jeromin A, Mikoshiba K, Goshima Y, Takei K (2009) Regulation of neurite outgrowth mediated by neuronal calcium sensor-1 and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in nerve growth cones. Neuroscience 161(3):743–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, Khodthong C, Kowalchyk JA, Martin TF (2008) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates SNARE-dependent membrane fusion. J Cell Biol 182:355–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J, Heon S, Kim MJ, Son GH, Park Y, Henley JM, Weiss JL, Sheng M, Collingridge GL, Cho K (2008) Metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated LTD involves two interacting Ca2+ sensors, NCS-1 and PICK1. Neuron 60(6):1095–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani N, Negyessy L, Lin R, Goldman-Rakic P, Levenson R (2002) Interaction with Neuronal Calcium Sensor NCS-1 mediates desensitization of the D2 Dopamine Receptor. J Neurosci 22:8476–8486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi S, Rosa P, Willars GB, Challiss RAJ, Taverna E, Francolini M, Bootman MD, Lipp P, Inoue K, Roder J, Jeromin A (2002) Mechanisms underlying the neuronal calcium sensor-1 evoked enhancement of exocytosis in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 277:30315–30324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konur S, Ghosh A (2005) Calcium signaling and the control of dendritic development. Neuron 46(3):401–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan IB (1999) It is calmodulin after all! Mediator of the calcium modulation of multiple ion channels. Neuron 22(4):645–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TFJ (2005) PI(4, 5)Pregulation of surface membrane traffic. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13:493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TFJ, Loyet KM, Barry VA, Kowalchyk JA (1997) The role of PtdIns(4, 5)P2 in exocytotic membrane fusion. Biochem Soc Trans 25:1137–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFerran BW, Graham ME, Burgoyne RD (1998) Neuronal Ca2+ sensor 1, the mammalian homologue of Frequenin, is expressed in chromaffin and PC12 cells and regulates neurosecretion from dense-core granules. J Biol Chem 273(35):22768–22772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFerran BW, Weiss JL, Burgoyne RD (1999) Neuronal Ca2+ sensor 1. Characterization of the myristoylated protein, its cellular effects in permeabilized adrenal chromaffin cells, Ca2+-independent membrane association, and interaction with binding proteins, suggesting a role in rapid Ca2+ signal transduction. J Biol Chem 274(42):30258–30265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis IE, Zhang Y, Yang J (2007) The lipid connection-regulation of voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels by phosphoinositides. Pflugers Arch 455(1):147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosevic I, Sørensen JB, Lang T, Krauss M, Nagy G, Haucke V, Jahn R, Neher E (2005) Plasmalemmal phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate level regulates the releasable vesicle pool size in chromaffin cells. J Neurosci 25:2557–2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman SJ, Hume RI (1993) Omega-conotoxin prevents myelin-evoked growth cone collapse in neonatal rat locus coeruleus neurons in vitro. J Neurosci 13:4727–4736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A, Burgoyne RD (1997) Common mechanisms for regulated exocytosis in the chromaffin cell and the synapse. Semin Cell Dev Biol 8:141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura TY, Jeromin A, Smith G, Kurushima H, Koga H, Nakabeppu Y, Wakabayashi S, Nabekura J (2006) Novel role of neuronal Ca2+ sensor-1 as a survival factor up-regulated in injured neurons. J Cell Biol 172(7):1081–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan DW, Ivings L, Weiss JL, Ashby MC, Tepikin AV, Burgoyne RD (2002) Differential use of myristoyl groups on neuronal calcium sensor proteins as a determinant of spatio-temporal aspects of Ca2+ signal transduction. J Biol Chem 277(16):14227–14237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan CY, Jeromin A, Lundstrom K, Yoo SH, Roder J, Fox AP (2002) Alterations in exocytosis induced by neuronal Ca2+ sensor-1 in bovine chromaffin cells. J Neurosci 22(7):2427–2433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen OH, Cancela JM (2000) Nerve guidance: attraction or repulsion by local Ca2+ signals. Curr Biol 10(8):R311–R314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongs O, Lindemeier J, Zhu XR, Theil T, Engelkamp D, Krah-Jentgens I, Lambrecht HG, Koch KW, Schwemer J, Rivosecchi R, Mallart A, Galcerane J, Canale I, Barbase JA, Ferrús A (1993) Frequenin—a novel calcium-binding protein that modulates synaptic efficacy in the Drosophila nervous system. Neuron 11(1):15–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohacs T (2007) Regulation of TRP channels by PIP2. Pflugers Arch 453(6):753–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset MCT, Gavarini S, Jeromin A, Charnet P (2003) Down-regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by neuronal calcium sensor-1 is beta subunit-specific. J Biol Chem 278(9):7019–7026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab B, Georgiou J, Nath A, Lee FJ, Wang M, Michalon A, Liu F, Mansuy IM, Roder JC (2009) NCS-1 in the dentate gyrus promotes exploration, synaptic plasticity, and rapid acquisition of spatial memory. Neuron 63(5):643–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlecker C, Boehmerle W, Jeromin A, DeGray B, Varshney A, Sharma Y, Szigeti-Buck K, Ehrlich BE (2006) Neuronal Calcium Sensor-1 enhancement of InsP3 receptor activity is inhibited by therapeutic levels of lithium. J Clin Invest 116(6):1668–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Hille B (2008) PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu Rev Biophys 37:175–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Leal K, Hille B (2010) Modulation of high-voltage activated Ca2+ channels by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Neuron 67:224–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebak M, Lemonnier L, DeHaven WI, Wedel BJ, Bird GS, Putney JW Jr (2009) Complex functions of phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate in regulation of TRPC5 cation channels. Pflugers Arch 457(4):757–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto T, Jeromin A, Saitoh N, Roder JC, Takahashi T (2002) Neuronal calcium sensor 1 and activity-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type calcium channel currents at presynaptic nerve terminals. Science 295:2276–2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viard P, Butcher AJ, Halet G, Davies A, Nurnberg B, Heblich F, Dolphin AC (2004) PI3 K promotes voltage-dependent calcium channel trafficking to the plasma membrane. Nat Neurosci 7(9):934–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C-Y, Yang F et al (2001) Ca2+ binding protein Frequenin mediates GDNF-induced potentiation of Ca2+ channels and transmitter release. Neuron 32:99–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JL, Burgoyne RD (2001) Voltage-independent inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in adrenal chromaffin cells via a neuronal Ca2+ sensor-1-dependent pathway involves Src-family tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem 276:44804–44811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JL, Burgoyne RD (2002) Sense and sensibility in the regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Trends Neurosci 25(10):489–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JL, Archer DA, Burgoyne RD (2000) Neuronal Ca2+ sensor-1/Frequenin functions in an autocrine pathway regulating Ca2+ channels in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem 275(51):40082–40087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EJ, Doherty P, Turner G, Reid RA, Hemperly JJ, Walsh FS (1992) Calcium influx into neurons can solely account for cell contact-dependent neurite outgrowth stimulated by transfected L1. J Cell Biol 119:883–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winks JS, Hughes S, Filippov AK, Tatulian L, Abogadie FC, Brown DA, Marsh SJ (2005) Relationship between membrane phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate and receptor-mediated inhibition of native neuronal M channels. J Neurosci 25(13):3400–3413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes RC, Bauer CS, Khan SU, Weiss JL, Seward EP (2007) Differential regulation of endogenous N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel inactivation by Ca2+/calmodulin impacts on their ability to support exocytosis in chromaffin cells. J Neurosci 27(19):5236–5248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Kwan HY, Huang Y (2005) Regulation of TRP channels by phosphorylation. Neurosignals 14(6):273–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip PK, Wong LF, Sears TA, Yanez-Munoz RJ, McMahon SB (2010) Cortical overexpression of Neuronal Calcium Sensor-1 induces functional plasticity in spinal cord following unilateral pyramidal tract injury in rat. PLoS Biol 8(6):1–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaika O, Tolstykh GP et al (2007) Inositol triphosphate-mediated Ca2+ signals direct purinergic P2Y receptor regulation of neuronal ion channels. J Neurosci 27(33):8914–8926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) Endogenous NCS-1 Staining in K+ Differentiated Chromaffin Cells. Left panel transmitted light image of living differentiated bovine adrenal chromaffin cells by K+ (55 mM) depolarization for 48 h in the presence of FBS. Bovine chromaffin cells were electroporated with DN TRPC5 plasmid and incubated for 48 h. 55 mM K+ was added into the growth media to differentiate them for 48 h prior to co-immunostaining. Cells were co-stained with anti-DBH (Dopamine β-Hydroxlase) to label chromaffin cell exocytotic vesicles (TRITC, A), anti-NCS-1 (FITC, B) and phalloidin (Alexa Flour® 350, C). D is the merged image of A, B and C, in which both NCS-1 and DBH are enriched in the cell body and the growth cone areas. E, F and G are enlarged image of growth cones from the merged areas in boxes from picture D. Arrows point to the neurite filopodia tips, which are stained with phalloidin labeling the polymerized actin. Note NCS-1 staining is not present in the filopodia tips. (b) DN NCS-1 in NGF Differentiated Double Mutant Expressing Chromaffin Cells. Left panel living differentiated bovine adrenal chromaffin cells differentiated by NGF (100 ng/ml) for 10 days in the absence of FBS. Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells were electroporated with DN NCS-1 and DN TRPC5 plasmids and incubated for 48 h. 100 ng/ml NGF was used in a FBS free growth media to differentiate them for 10 days prior to co-immunostaining. Cells were co-stained with anti-DBH (TRITC, A), anti-NCS-1 (FITC, B) and phalloidin (C). D is the merged image of A, B and C, in which both NCS-1 and DBH are enriched in the cell body and the growth cone areas. E, F and G are enlarged images of growth cones from the merged areas in boxes from picture D. Arrows point to filopodia tips to show lack of phalloidin staining (compare to (a)) and enrichment in NCS-1 and DBH staining overlay. H. Hui and J.L. Weiss, data in preparation. (TIFF 2380 kb)

(a) Quantification of NCS-1 Enrichment in Tips of Differentiated PC12 Cell Filopodia in DN/DN TRPC5/NCS-1 combination. PC12 cells transfected with cDNA constructs as indicated and fluorescence intensity of NCS-1 and tubulin staining was measured from digital photos using ImageJ software. Mean ± SEM **p < 0.001 shows significant differences via a students t-test of increased ratio value compared to the other cell groups (n = 25 cells/condition). H. Hui and J.L. Weiss, data in preparation. (b) Differential effects of NCS-1 over-expression on reporter growth hormone (GH) release from PC12. Cells were transfected with control or NCS-1 plasmid along with a GH encoding plasmid. After 3 days the cells were washed and challenged with (A) 300 mM ATP or (B) 55 mM KCl. Other cells (C) were permeabilized for 6 min by incubation in 20 mM digitonin and then challenged without (basal) or with 10 mM free Ca2+. After incubation for 15 min cellular GH and GH present in the medium were assayed and released GH expressed as a percentage of total GH. The extent of release was then normalized to the mean value of release for control stimulated cells. The data are shown as mean + SEM (n = 6). M.E. Graham and R.D. Burgoyne, data in preparation. (TIFF 2380 kb)