Abstract

Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) has recently been shown to be involved in two genetic disorders of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in children. These include the Hyperinsulinism / Hyperammonemia Syndrome caused by dominant activating mutations of GLUD1 which interfere with inhibitory regulation by GTP and hyperinsulinism due to recessive deficiency of short-chain 3-hydroxy-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCHAD, encoded by HADH1). The clinical manifestations of the abnormalities in pancreatic ϐ-cell insulin regulation include fasting hypoglycemia, as well as protein-sensitive hypoglycemia. The latter is due to abnormally increased sensitivity of affected children to stimulation of insulin secretion by the amino acid, leucine. In patients with GDH activating mutations, mild hyperammonemia occurs in both the basal and protein-fed state, possibly due to increased renal ammoniagenesis. Some patients with GDH activating mutations appear to be at unusual risk of developmental delay and generalized epilepsy, perhaps reflecting consequences of increased GDH activity in the brain. Studies of these two disorders have been carried out in mouse models to define the mechanisms of insulin dysregulation. In SCHAD deficiency, the activation of GDH is due to loss of a direct inhibitory protein-protein interaction between SCHAD and GDH. These two novel human disorders demonstrate the important role of GDH in insulin regulation and illustrate unexpectedly important reasons for the unusually complex allosteric regulation of GDH.

Keywords: hypoglycemia, hyperinsulinism, beta-cell, insulin, leucine-sensitive, genetic disorders, children

Introduction

Although the enzyme, glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), has been well studied for many years, its physiologic role and the rationale for having so many allosteric effectors of a freely reversible enzyme step has remained a mystery. Recent discoveries of two novel genetic disorders that cause severe hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in infants and children have provided an opportunity to resolve some of these mysteries surrounding GDH and to add some new twists to its physiologic roles. The first disorder, the Hyperinsulinism-Hyperammonemia Syndrome, is caused by mutations of GDH that lead to an activation of enzyme activity 1, 2. The second disorder, SCHAD deficiency, caused by inactivating mutations of the short chain fatty-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, leads to an activation of GDH due to a loss of an inhibitory interaction of the SCHAD protein on GDH enzymatic activity 3, 4. The predominant clinical feature of these two disorders, hyperinsulinism, reflects altered pancreatic beta cell insulin regulation; however, the HI/HA disorder includes additional manifestations that reflect the function of GDH in other tissues, namely brain and either kidney or liver. Both disorders illustrate the importance of allosteric regulation of GDH by small molecules and, unexpectedly, by other mitochondrial matrix peptides.

The GDH reaction and allosteric effectors

As described in more detail in other chapters in this collection, GDH is a mitochondrial matrix enzyme that catalyzes the reversible oxidation of glutamate to alpha-ketoglutarate and ammonia, using either NAD+ or NADP+ as co-factor. Enzyme expression is limited to specific tissues, such as liver, renal tubules, brain, and pancreatic beta cells; the enzyme is specifically not expressed in muscle. GDH is positively regulated by ADP and by leucine and is negatively regulated by GTP5, 6. Other negative effectors include palmitoyl-CoA and steroid hormones (e.g., diethylstilbestrol); recently, a green tea polyphenol, EGCG, has been identified to also be a negative effector 7. There has been much uncertainty about whether the GDH reaction operates reversibly in vivo or whether it has a preferred direction in specific organs. Evidence described in other chapters suggests that the reaction runs toward glutamate synthesis in liver and towards glutamate oxidation in brain. As described below, based on studies of the HI/HA Syndrome and SCHAD deficiency hyperinsulinism, GDH appears to operate exclusively in the oxidative deamination direction in pancreatic beta-cells.

The HI/HA Syndrome

The identification of GDH as the locus for the HI/HA Syndrome was first suggested by the unusual clinical phenotype of children afflicted with the disorder 2. These children present with recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia which are due to dysregulation of insulin regulation. HI/HA is the second most common of a group of at least 7 different genetic forms of congenital hyperinsulinism 8. Examples of parent-to-child familial transmission of HI/HA in the first cases identified indicated that the disorder was autosomal dominantly expressed. The presenting feature of HI/HA children is recurrent episodes of symptomatic hypoglycemia which may result in seizures or permanent brain damage. Although this intermittent hypoglycemia is present from birth onwards, affected infants are often not recognized until later in childhood or even adulthood. Symptomatic episodes are frequently misinterpreted as epilepsy and the hypoglycemia not detected.

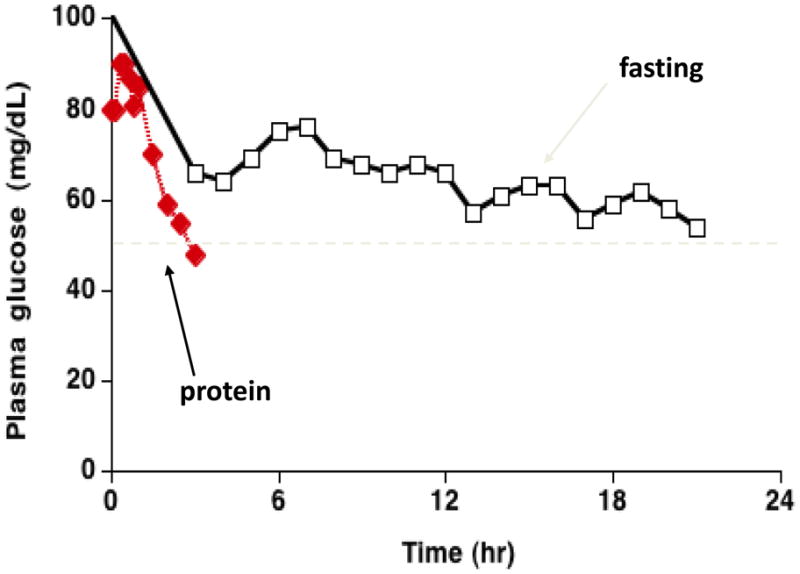

Hypoglycemia in HI/HA can be provoked by fasting. However, children with HI/HA are also extremely susceptible to protein-induced hypoglycemia. Therefore symptomatic hypoglycemia episodes often occur shortly after a meal. This is illustrated in Fig 1, which shows a teen-age girl with HI/HA who displayed a rather gradual onset of hypoglycemia after 12–18 hr of fasting, but became dramatically hypoglycemic within 3 hours after eating a protein meal 9. This phenomenon of “protein-sensitive” hypoglycemia was first recognized in children in the 1950s; it was also found that protein-sensitive individuals could develop hypoglycemia when given leucine (“leucine-sensitive” hypoglycemia) 10.

Fig 1.

Fasting vs. Protein-induced Hypoglycemia in a teen-age patient with the HI / HA Syndrome. Note the rapid onset of hypoglycemia after a protein meal compared to the more gradual development of hypoglycemia during fasting (modified from 9).

The other distinctive feature of the HI/HA Syndrome is a persistent elevation of plasma ammonia concentrations. This is illustrated in Table 1 which compares the plasma ammonia responses to a protein meal in children with HI/HA and controls. In the HI/HA children, baseline ammonia levels are 4–5 times greater than normal (although not as high as levels seen in patients with urea cycle enzyme defects-UCED). Following the protein load, plasma ammonia rises very slightly in HI/HA children 9; this also contrasts with the UCEDs in which a protein load can rapidly induce severe, life-threatening hyperammonemia. The hyperammonemia in HI/HA syndrome is not associated with the signs of CNS ammonia toxicity seen in UCEDs, such as lethargy, headache, vomiting, coma. It remains unclear whether the elevation of ammonia in HI/HA has pathologic consequences for patients or whether it is simply an easily recognized diagnostic feature. Efforts to treat the hyperammonemia with agents that are used for UCEDs, such as, benzoate or N-carbamoyl-glutamate, have not shown clear benefits11. This suggests that the hyperammonemia may not be due to defective ammonia detoxification by the liver urea cycle enzymes. Plasma amino acid concentrations in HI/HA are also remarkably normal, with the exception that plasma glutamine concentrations are lower than would be expected for the degree of hyperammonemia (which typically is associated with elevations of glutamine)2.

Table 1.

Hyperammonemia in children with HI/HA Syndrome (from ref 9, Hsu et al J Ped 2001)

| Normals (n=8) | HI/HA patients (n=14) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline plasma ammonia (μM) | 15–35 | 70–145 |

| Plasma ammonia increment after oral protein (μM) | 10 ± 1 | 22 ± 7 (p = NS) |

Hypoglycemia in patients with HI/HA responds readily to treatment with diazoxide, a beta-cell ATP-dependent potassium-channel (KATP) agonist which suppresses insulin secretion. Protein-restriction is sometimes useful to avoid postprandial hypoglycemia, although adequate doses of diazoxide usually suffice.

Identification of GDH as a candidate locus for the Syndrome

The combination of hyperinsulinism and hyperammonemia suggested that the HI/HA Syndrome involved amino acid metabolism in the insulin-secreting in pancreatic beta-cells, perhaps a step related to amino acid stimulated insulin secretion. While it was known that a number of amino acids could affect insulin release, one of the most specific was the stimulation of insulin release by leucine or by its non-metabolizable analog, BCH. In addition to the fact that leucine-sensitive hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinemism were associated historically, it had been suggested by Malaisse and colleagues in the 1980s that leucine and BCH stimulated insulin release by virtue of their allosteric stimulatory effect on GDH. As diagrammed in Figure 2, insulin secretion is stimulated by oxidation of glucose via an increase in ATP/ADP ratio which leads to closure of ATP-sensitive KATP channels, membrane depolarization, activation of voltage-gated calcium channels, an increase in cytosolic calcium, and a mobilization of insulin-containing vesicles to release insulin into the circulation. In similar fashion, amino acids can trigger release of insulin in response to the oxidation of amino acids through glutamate via GDH into the TCA cycle under allosteric activation of GDH by leucine. Activation of GDH could also explain the hyperammonemia in HI/HA by (1) increased oxidation of glutamate to release ammonia in tissues such as liver or kidney and (2) potentially, also by a lowering of the levels of glutamate needed to form N-acetyl-glutamate, an obligate allosteric activator of the first step in hepatic ureagenesis, carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase. For these mechanisms to work, it was postulated that (1) the GDH reaction needs to run in the direction of glutamate oxidation in beta-cells, (2) that insulin release is triggered by activation of GDH (e.g., by its allosteric effector, leucine), and (3) that HI/HA mutations would cause an activation of GDH by altering one or more of its allosteric regulatory sites.

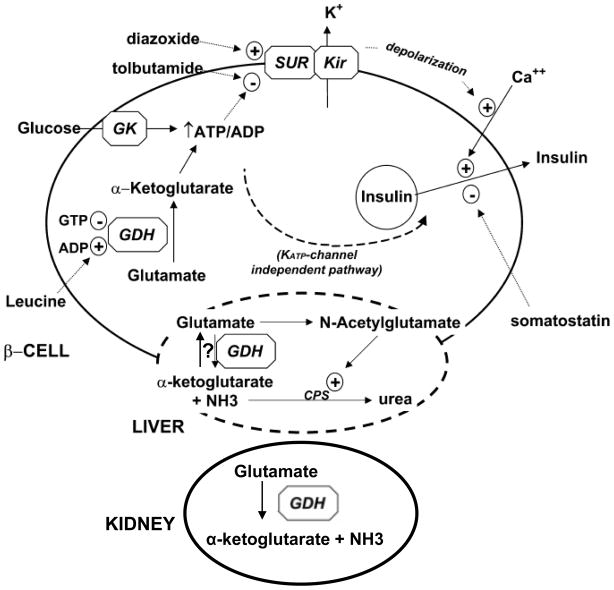

Figure 2.

Role of GDH in the Hyperinsuliinism / Hyperammonemia Syndrome. In the ϐ-cell, GDH is activated by leucine to trigger insulin release in response to amino acids (protein meal). The increased oxidation of glutamate increases the ATP/ADP ratio leading to closure of the plasma membrane ATP-dependent potassium channel via the sulfonylurea receptor (SUR1), membrane depolarization, opening of voltage-gated calcium channels, increase in cytosolic calcium, and release of insulin from stored granules. In the liver, glutamate may be a source of ammonia, as well as a substrate for formation of N-acetylglutamate which is a required allosteric activator of the first step in urea synthesis. However, note that the direction of GDH in liver may be toward glutamate synthesis rather than oxidation. In the kidney, oxidation of glutamate via GDH provides ammonia in adaptation to acidemia. Uncontrolled GDH activity leads to excessive release of insulin in ϐ-cells and excessive ammonia production (primarily in kidney).

Clinical pathophysiology of HI/HA syndrome

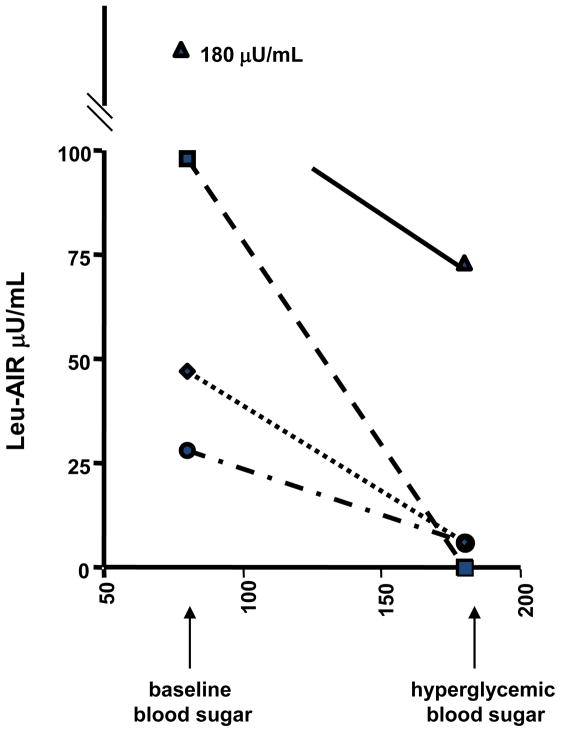

As noted above, patients with HI/HA become hypoglycemic with fasting and after protein meals. To test whether their hypoglycemia is associated with hypersensitivity to leucine stimulation, we examined the acute insulin responses to an intravenous bolus of leucine (leucine-AIR) 12. Following the bolus of leucine which increases plasma leucine transiently to 0.5–1 mM, HI/HA patients displays a very brisk increase in plasma insulin to values that may exceed 100 μU/mL; in contrast, normal individuals show almost no insulin response to leucine-AIR. When testing was performed under hyper-glycemic clamp conditions in HI/HA patients, the leucine-AIR was suppressed at high glucose (Fig 3). As shown below, this correlates well with in-vitro studies using isolated islets expressing the H454Y GDH activating mutation in which raising the ϐ-cell ATP/ADP ratio by exposure to high glucose suppresses GDH-mediated insulin release.

Figure 3.

Effect of hyperglycemia on leucine AIR in HI/HA children (based on data in Ref 28).

Genetic Mutations of GDH in HI/HA patients

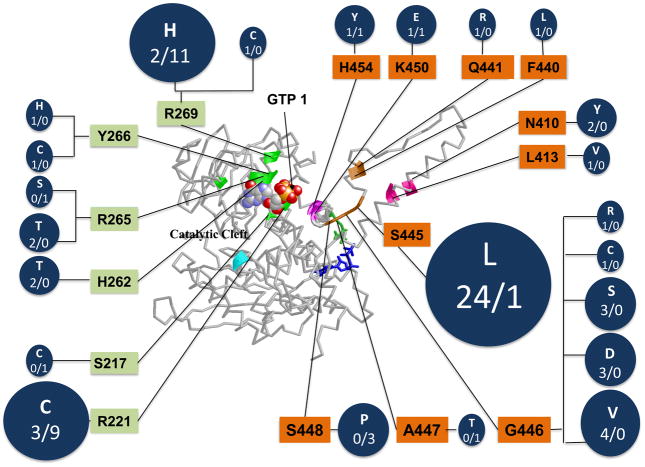

To test the hypothesis that GDH was the genetic locus for HI/HA, genomic DNA sequencing of the GDH GLUD1 gene was performed which revealed heterozygous missense mutations of GDH in affected children. As shown in Figure 4, all of these disease-causing mutations are located close to the inhibitory binding site for GTP, either affecting residues that interact directly with GTP binding or residues in the adjacent antenna region of the enzyme which cooperative communications among subunits of the GDH homohexamer 2, 11, 13. In 84 pedigrees examined to date, only 34% had familial transmitted mutations, while 66% were sporadic de novo mutations. A total of 23 different mutations have been identified, some of which clearly represent mutation hot-spots. In the series of patients with congenital HI at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, GDH mutations account for about a quarter of all diazoxide-responsive cases of genetic HI.

Fig 4.

Location and frequency of HI/HA mutations in GDH. Mutations indicated in circles as “sporadic”/”familial”; orange residues indicate exons 11&12 mutations, green residues indicagte exons 6&7 mutations. In the total of 84 cases, 66% were sporadic while 34% were familial.

Effects of HI/HA mutations on GDH enzyme kinetics

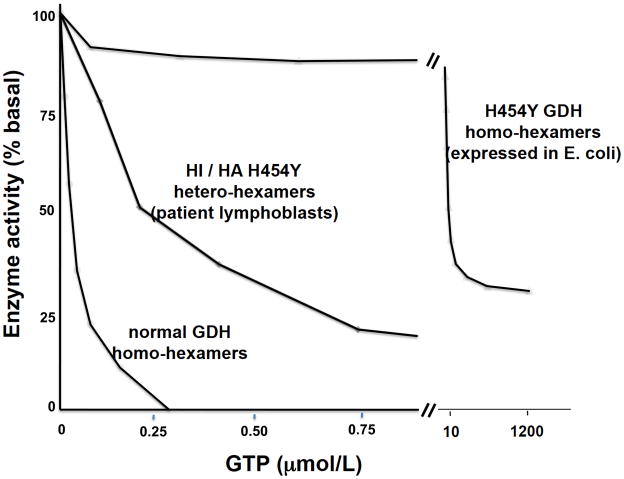

GDH enzyme kinetics have been examined in both extracts of patient lymphoblasts and in the pure mutant enzyme expressed in E. coli 14. As shown in Fig 5, the sensitivity of H454Y GDH from patient lymphoblasts to GTP inhibition is reduced about 10-fold; in contrast, the purified mutant enzyme is almost totally unresponsive to GTP. Table 2 summarizes the effects of 13 HI/HA mutations on GDH kinetics in patient lymphoblasts. The decrease in GTP sensitivity ranges from 1.3 to 10 fold less than normal. The effects on enzyme basal activity and responsiveness to other positive and negative allosteric effectors are relatively minor. For comparison, the GDH kinetics of the expressed S448P and H454Y mutations are also shown in Table 2. The H454Y mutation has a greater effect on GTP sensitivity compared to the S448Y mutation, although the latter reduces enzymatic activity rather dramatically. The various differences in mutant enzyme kinetics do not appear to have a clear effect on clinical phenotypes, such as the severity of hypoglycemic symptoms or responses to diazoxide. However, it has been suggested that mutations at residues directly involved in GTP binding may be associated with greater risk of developmental delay and seizures 15.

Figure 5.

GTP Sensitivity of HI / HA GDH (based on data from Ref 14 ).

Table 2.

GDH kinetics in HI/HA patient lymphoblasts and expressed S448P and H454Y mutants. Enzyme activity was measured in the reductive amination direction in extracts of cultured lymphoblasts or purified enzyme (from ref 11,13, 14).

| basal activity (nmol/min/mg) | IC50 values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activators | Inhibitors | |||||

| ADP μM | leucine μM | GTP nM | DES μM | palmitoyl-CoA μM | ||

| mutation | ||||||

| S217C | 14 | 24 | 680 | 110 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| R221C | 23 | 19 | 630 | 250 | 2 | 0.88 |

| R265T | 17 | 22 | 680 | 73 | 1.8 | 0.75 |

| R269C | 13 | 22 | 700 | 61 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| R269H | 19 | 21 | 700 | 73 | 1.7 | 0.87 |

| P440L | 22 | 21 | 700 | 190 | 2.1 | 0.6 |

| Q441R | 22 | 20 | 830 | 94 | 2.4 | 1.1 |

| S445L | 28 | 23 | 800 | 280 | 2.2 | 0.7 |

| G446R | 21 | 18 | 750 | 300 | 3.1 | 1.2 |

| G446D | 23 | 28 | 800 | 480 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| S448P | 10 | 34 | 1000 | 290 | 1.3 | 0.97 |

| K450E | 19 | 24 | 980 | 230 | 0.8 | 0.48 |

| H454Y | 19 | 13 | 710 | 280 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| normal (n=7, m±SD) | 22±2.3 | 19±3.4 | 800±120 | 48±17 | 1.9±0.2 | 0.68±0.35 |

| pure S448P | 19 | 21 | 610 | 3100 | 0.74 | 13 |

| pure H454Y | 74 | 9.1 | 470 | 210000 | 0.36 | 15 |

| normal | 84±9.5 | 12±4.5 | 640±110 | 42±12 | 1.7±0.24 | 30±5.4 |

Effects of HI/HA mutations on insulin secretion in vitro

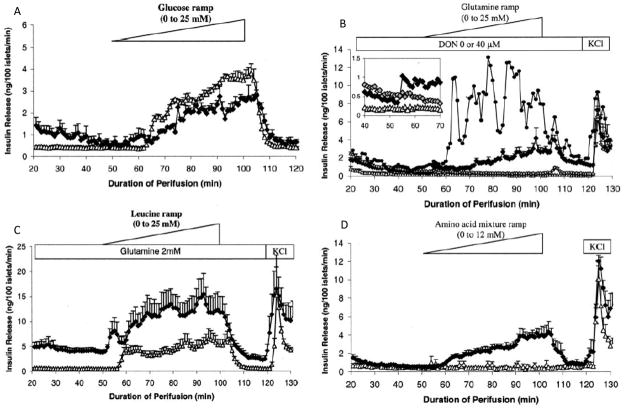

To study the effects of HI/HA GDH mutations on insulin regulation in isolated islets, the H454Y mutation was expressed in mouse beta-cells using a transgene driven by the rat insulin promoter 1. Islets were isolated from pancreas by collagenase digestion and cultured in media for 1–3 days prior to use in order to minimize contaminating exocrine tissue. Fig 6 shows that mouse islets expressing the H454Y huGDH transgene are much more sensitive than controls to stimulation with leucine (panel C) or to a mixture of amino acids (panel D), and are able to respond to stimulation with glutamine alone (panel B). These observations correlate well with the hyper-sensitivity to hypoglycemia following a protein meal that is seen in children with HI/HA.

Fig 6.

H454Y transgenic islet responses to fuel-mediated insulin release. Transgenic islets are indicated as black diamonds, controls as open triangles. In panel B, closed circles show islets from an H454Y transgenic line with increased transgene expression; inset grey diamonds show suppression of insulin release by glutaminase inhibition with 40 μM DON (reproduced from 1 with permission).

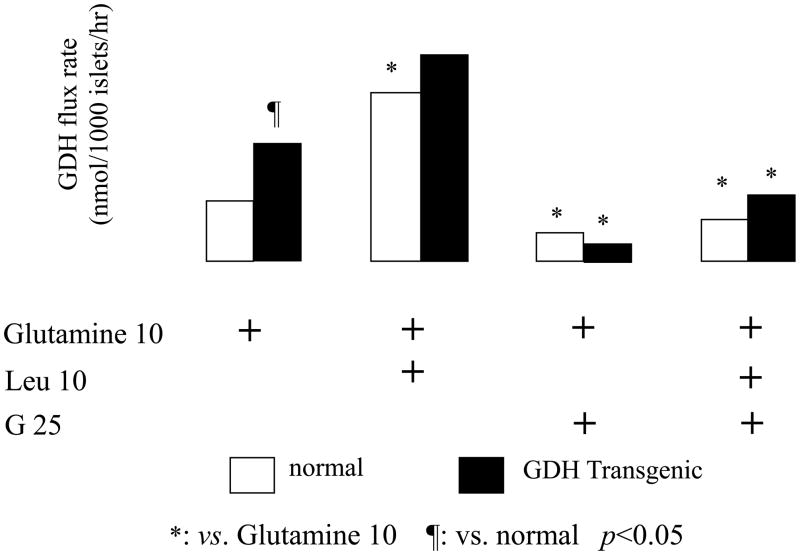

Effects of HI/HA mutations on flux through GDH

The effect of GDH activating mutations on GDH flux in the oxidative deamination direction has been demonstrated using 10 mM 15N-glutamine labeled in the C2 amino position to follow flux through glutaminase and GDH into alpha-ketoglutarate. As shown in Figure 7, in isolated islets expressing the H454Y hGDH activating mutation, GDH flux is increased in the basal state and can be further increased by leucine stimulation. Addition of 25 mM glucose suppresses this oxidative flux through GDH in both the transgenic islets and also in wild type islets. This glucose suppression of GDH cannot be overcome by leucine stimulation (cf Fig 5 suppression of leucine stimulated insulin secretion in HI/HA patients). Measurements of the reverse flux through GDH using 15N-ammonium showed no detectable incorporation into glutamate 1. These experiments indicate that GDH operates essentially unidirectionally in the oxidative deamination direction in both HI/HA mutant and normal islets.

Figure 7.

GDH flux in H454Y transgenic islets in the presence of 25 mM glucose, 10 mM leucine, and 10 mM [2–15N]-glutamine.

Mechanism of hyperammonemia in the HI/HA syndrome

Originally, we had suggested that the activation of GDH enzymatic activity in liver was responsible for hyperammonemia in HI/HA children2. We proposed that increased GDH in liver led to increased glutamate oxidation resulting in increased ammonia production; we also proposed that the lowering of glutamate levels in liver would slow ammonia conversion to urea by impairing formation of N-acetyl-glutamate, an obligate allosteric activator of the first step in ureagenesis, carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2. Recently, however, Brosnan and colleagues have provided experimental evidence in rats that increases in plasma ammonia levels associated with activation of GDH by the leucine analog, 2-aminobicyclo[2,2,1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH), are due to increased ammonia production by the kidney and not to ammonia production in liver 16, 17. This provides a nice correlation with the evidence that renal ammoniagenesis through GDH is an important pathway for renal compensation for acidosis18.

CNS manifestations in children with HI/HA syndrome

As noted above, there has not been clear evidence that the persistent elevations of plasma ammonia have a clinical effect in children with HI/HA. However, recent observations suggest that affected children do have abnormal CNS manifestations. Raizen et al reported that seizures were unusually common in HI/HA children, occurring in 9 of 14 cases; 6 of these 9 had persistent seizures in the absence of hypoglycemia 19. In 4 of these 9, there was an unusual frequency of absence-type seizures with an EEG pattern of generalized epilepsy which is quite unlike the grand mal seizures that are more typical of epilepsy due to hypoglycemic brain damage. A report from the Paris hyperinsulinism center identified developmental delays in a large proportion of their HI/HA case series and an increased frequency of hyperactivity/attention deficit behavior disorders; this series also confirmed the susceptibility of HI/HA children to generalized epilepsy 15. Since brain is one of the tissues that expresses GDH at high levels, it seems likely that the HI/HA GDH activating mutations may have direct effects on the brain. Further work in this area is necessary.

Dysregulation of GDH in Hyperinsulinism Caused by Deficiency of Short-Chain 3-OH-acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase (SCHAD, HADH)

Clinical Features of Children with SCHAD Deficiency. More than 8 children have been recognized in which congenital hyperinsulinism is associated with a recessively-transmitted deficiency of SCHAD 3, 20–22. All of the affecteds presented in early childhood with episodes of hypoglycemia that responded well to treatment with diazoxide. A distinguishing feature in some of the cases (but possibly not all) was abnormal accumulations of upstream metabolites: 3-OH-butyryl carnitine in plasma and of 3-OH-glutaric acid in urine. SCHAD is a mitochondrial matrix enzyme which catalyzes the penultimate step in fatty acid beta-oxidation for short and medium-chain fatty acids (C4–C12 in length) 23. A large number of other genetic defects in fatty acid oxidation are known, but none of them cause hypoglycemia by dysregulation of insulin secretion. 24

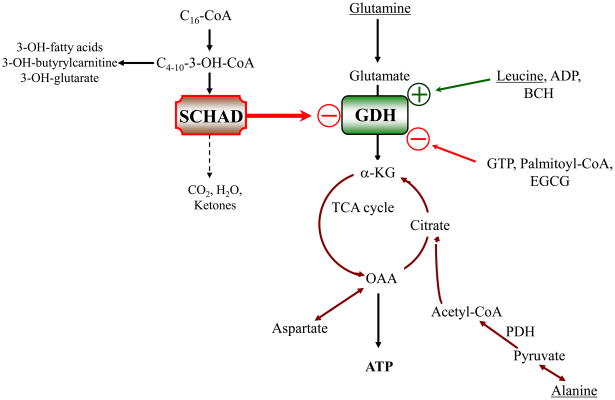

It was recently reported that children affected with SCHAD deficiency also have protein-sensitive hypoglycemia, which suggests that the mechanism of hyperinsulinism in this disorder might be similar to the HI/HA syndrome and involve GDH 25. In addition, Filling, et al recently reported that GDH was one of several proteins that associated with SCHAD in pull-down experiments using rat liver mitochondrial extracts23. On the other hand, it had been suggested that SCHAD deficiency produced exaggerated insulin responses to glucose stimulation through accumulations of fatty acyl-CoA substrates upstream of the SCHAD step 22, 26. Using mice with a global knock-out of SCHAD we have investigated these potential explanations for SCHAD HI and, as recently reported, have provided evidence of activation of GDH activity in isolated islets from SCHAD −/− mice 4. Unlike the HI/HA syndrome, the activation of GDH in SCHAD deficiency appears to be largely limited to pancreatic beta-cells, since deficiency of the enzyme does not lead to hyperammonemia in either affected patients or in the mouse knock-out model.

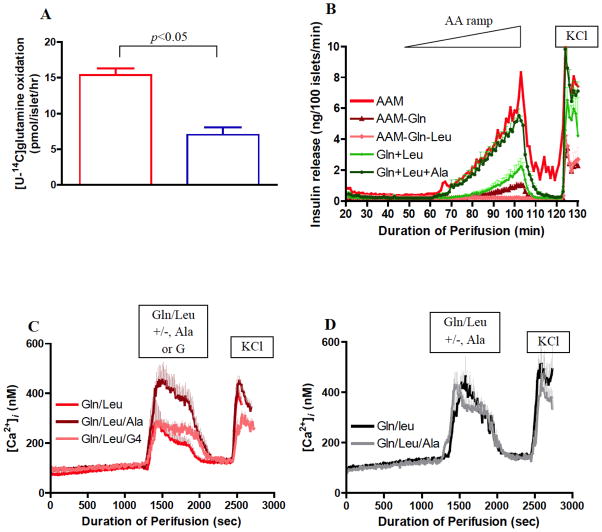

As shown in Fig 8, islets from SCHAD −/− show evidence that glutaminolysis and glutamate oxidation via GDH are activated and produce altered regulation of insulin secretion similar to islets with activating mutations of GDH 4. Oxidation of labeled glutamine is increased in SCHAD −/− islets, similar to islets expressing a GDH activating mutation. As shown in panel B, the SCHAD −/− islets respond to a physiologic mixture of amino acids given as a ramp, whereas normal islets are unresponsive. Unlike islets with an activated mutant GDH, however, SCHAD −/−islets do not show an increase in cytosolic calcium in response to glutamine alone (Panels C and D). Instead, maximal rates of insulin release required leucine and alanine, in addition to glutamine (Panel B). This suggests that the degree of GDH activation in SCHAD deficiency is less than with GDH activating mutations associated with the HI/HA syndrome and that alanine is required to facilitate TCA cycle turnover of alpha-ketoglutarate released by GDH.

Fig 8.

Studies of SCHAD−/− islets. A. Increased glutaminolysis. B. Increased responsiveness to amino acid mixture. C. Calcium response in SCHAD−/− islets requires glutamine + leucine + alanine. D. In contrast, islets with GDH activating mutation respond without alanine (reproduced from 4 with permission).

As shown in Table 3, studies of GDH kinetics in islets from SCHAD deficient mice showed a rather specific increase in the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate (alpha-ketoglutarate, in the assay used), consistent with a 50% increase in GDH enzyme efficiency, as determined by the ratio of Vmax to Km 4. This is consistent with evidence from Filling, et al and confirmed in the SCHAD −/− mice, that SCHAD forms a protein-protein association with GDH. As shown in Fig 9, we have proposed that, in addition to the well-known allosteric effectors of GDH such as GTP, SCHAD protein acts as an inhibitory regulator of GDH enzyme activity. In this way, mutations which lead to an absence of SCHAD protein lead to an abnormal activation of GDH, at least in pancreatic beta-cells, which results in hyperinsulinism.

Table 3.

GDH kinetics in SCHAD−/− islets. GDH activity was measured in the reductive amination direction using homogenates of isolated islets (from ref 4).

| SCHAD−/− | normal | |

|---|---|---|

| GDH activity (nmol/mg prot/min) | ||

| basal | 25±1 | 28±4 |

| maximal | 84±2 | 88±8 |

| ADP ED50 (μM) | 13±3 | 8±2 |

| GTP ED50 (nM) | 280–±28 | 309±17 |

| alpha-KG Km (μM) | 63±4 | 107±8 |

Figure 9.

SCHAD acts via a “moonlighting protein” effect to inhibit GDH enzymatic activity in pancreatic ϐ-cells.

Conclusion

The addition of a regulatory system for GDH that involves protein effectors, as well as small molecule allosteric modulators, increases the complexity of the systems for controlling GDH activity. It was recently suggested that GDH activity can also be modulated covalently by SIRT4, one of the sirtuin proteins related to increased longevity associated with calorie restriction 27. As noted in another article in this series by Dr. Thomas Smith, GDH activity is potently inhibited by a green tea polyphenol, EGCG, suggesting that GDH might be responsive to modulation by diet or other environmental factors. Clearly, the examples of hyperinsulinism caused by two disorders of GDH regulation, the HI/HA syndrome and SCHAD deficiency, demonstrate that allosteric regulation of GDH is of great importance in normal physiologic homeostasis in humans.

Research Highlights.

GDH is involved in two forms of congenital hyperinsulinism

These disorders illustrate the importance of allosteric regulation of GDH

Dominant activating mutations of GDH cause the Hyperinsulinism / Hyperammonemia Syndrome

Recessive mutations of short-chain 3-OH-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase also cause hyperinsulinism

The mechanism of HI due to SCHAD deficiency is loss of its inhibitory protein-protein interaction with GDH

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (RO1-DK 56268, DK 53012, UL1-RR024134, and S10-RR026853) and RO1-DK072171 (to T.J. Smith). We thank the University of Pennsylvania Diabetes and Endocrinology Center (DERC) for the use of the Islet and Radioimmunoassay Cores (P30-DK19525). Contributors to the work included Dr. ChanHong Li, Dr. Andrea Kelly, Ms. Courtney MacMullen, Dr. Michael Bennett, Dr. Marc Yudoff, Dr. Itzhak Nissim, Dr. Franz Matschinsky, and, especially, Dr. Thomas J. Smith.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Li C, Matter A, Kelly A, et al. Effects of a GTP-insensitive mutation of glutamate dehydrogenase on insulin secretion in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15064–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanley CA, Lieu YK, Hsu BY, et al. Hyperinsulinism and hyperammonemia in infants with regulatory mutations of the glutamate dehydrogenase gene. The New England journal of medicine. 1998;338:1352–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton PT, Eaton S, Aynsley-Green A, et al. Hyperinsulinism in short-chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency reveals the importance of beta-oxidation in insulin secretion. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:457–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI11294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C, Chen P, Palladino A, et al. Mechanism of hyperinsulinism in short-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency involves activation of glutamate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith TJ, Stanley CA. Untangling the glutamate dehydrogenase allosteric nightmare. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith TJ, Schmidt T, Fang J, Wu J, Siuzdak G, Stanley CA. The structure of apo human glutamate dehydrogenase details subunit communication and allostery. Journal of molecular biology. 2002;318:765–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li C, Allen A, Kwagh J, et al. Green tea polyphenols modulate insulin secretion by inhibiting glutamate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10214–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512792200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Leon DD, Stanley CA. Mechanisms of Disease: advances in diagnosis and treatment of hyperinsulinism in neonates. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:57–68. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu BY, Kelly A, Thornton PS, Greenberg CR, Dilling LA, Stanley CA. Protein-sensitive and fasting hypoglycemia in children with the hyperinsulinism/hyperammonemia syndrome. J Pediatr. 2001;138:383–9. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochrane WA, Payne WW, Simpkiss MJ, Woolf LI. Familial hypoglycemia precipitated by amino acids. J Clin Invest. 1955;35:411–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI103292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanley CA, Fang J, Kutyna K, et al. Molecular basis and characterization of the hyperinsulinism/hyperammonemia syndrome: predominance of mutations in exons 11 and 12 of the glutamate dehydrogenase gene. HI/HA Contributing Investigators. Diabetes. 2000;49:667–73. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly A, Ferry RJ, Grimberg A, Koo-McCoy S, Stanley CA. Acute insulin responses to leucine: A diagnostic tool for the hyperinsulinism / hyperammonemia syndrome. Pediatr Res. 1999;45:92A. SPR meeting abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacMullen C, Fang J, Hsu BYL, et al. Hyperinsulinism / hyperammonemia syndrome in children with regulatory mutations in the inhibitory GTP binding domain of glutamate dehydrogenase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1782–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang J, Hsu BY, MacMullen CM, Poncz M, Smith TJ, Stanley CA. Expression, purification and characterization of human glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) allosteric regulatory mutations. The Biochemical journal. 2002;363:81–7. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahi-Buisson N, Roze E, Dionisi C, et al. Neurological aspects of hyperinsulinism-hyperammonaemia syndrome. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2008;50:945–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treberg JR, Brosnan ME, Watford M, Brosnan JT. On the reversibility of glutamate dehydrogenase and the source of hyperammonemia in the hyperinsulinism/hyperammonemia syndrome. Adv Enzyme Regul. 50:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2009.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treberg JR, Clow KA, Greene KA, Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT. Systemic activation of glutamate dehydrogenase increases renal ammoniagenesis: implications for the hyperinsulinism/hyperammonemia syndrome. American journal of physiology. 2010;298:E1219–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00028.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen OE, Kalhan SC, Hanson RW. The key role of anaplerosis and cataplerosis for citric acid cycle function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30409–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raizen DM, Brooks-Kayal A, Steinkrauss L, Tennekoon GI, Stanley CA, Kelly A. Central nervous system hyperexcitability associated with glutamate dehydrogenase gain of function mutations. J Pediatr. 2005;146:388–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain K, Clayton PT, Krywawych S, et al. Hyperinsulinism of infancy associated with a novel splice site mutation in the SCHAD gene. J Pediatr. 2005;146:706–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molven A, Matre GE, Duran M, et al. Familial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia caused by a defect in the SCHAD enzyme of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Diabetes. 2004;53:221–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton S, Chatziandreou I, Krywawych S, Pen S, Clayton PT, Hussain K. Short-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency associated with hyperinsulinism: a novel glucose-fatty acid cycle? Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1137–9. doi: 10.1042/bst0311137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filling C, Keller B, Hirschberg D, et al. Role of short-chain hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenases in SCHAD deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanley CA. New genetic defects in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and carnitine deficiency. Advances in pediatrics. 1987;34:59–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapoor RR, James C, Flanagan SE, Ellard S, Eaton S, Hussain K. 3-Hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia: characterization of a novel mutation and severe dietary protein sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2221–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martens GA, Vervoort A, Van de Casteele M, et al. Specificity in beta cell expression of L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short chain, and potential role in down-regulating insulin release. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21134–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R, Haigis KM, et al. SIRT4 inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase and opposes the effects of calorie restriction in pancreatic beta cells. Cell. 2006;126:941–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly A, Ng D, Ferry RJ, Jr, et al. Acute insulin responses to leucine in children with the hyperinsulinism/hyperammonemia syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3724–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]