Abstract

To determine whether serine/threonine ROCK1 is activated by insulin in vivo in humans and whether impaired activation of ROCK1 could play a role in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance, we measured the activity of ROCK1 and the protein content of the Rho family in vastus lateralis muscle of lean, obese nondiabetic, and obese type 2 diabetic subjects. Biopsies were taken after an overnight fast and after a 3-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp. Insulin-stimulated GDR was reduced 38% in obese nondiabetic subjects compared with lean, 62% in obese diabetic subjects compared with lean, and 39% in obese diabetic compared with obese nondiabetic subjects (all comparisons P < 0.001). Insulin-stimulated IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation is impaired 41–48% in diabetic subjects compared with lean or obese subjects. Basal activity of ROCK1 was similar in all groups. Insulin increased ROCK1 activity 2.1-fold in lean and 1.7-fold in obese nondiabetic subjects in muscle. However, ROCK1 activity did not increase in response to insulin in muscle of obese type 2 diabetic subjects without change in ROCK1 protein levels. Importantly, insulin-stimulated ROCK1 activity was positively correlated with insulin-mediated GDR in lean subjects (P < 0.01) but not in obese or type 2 diabetic subjects. Moreover, RhoE GTPase that inhibits the catalytic activity of ROCK1 by binding to the kinase domain of the enzyme is notably increased in obese type 2 diabetic subjects, accounting for defective ROCK1 activity. Thus, these data suggest that ROCK1 may play an important role in the pathogenesis of resistance to insulin action on glucose disposal in muscle of obese type 2 diabetic subjects.

Keywords: Rho-kinase 1

skeletal muscle is the primary site of glucose disposal in the insulin-stimulated state (7). Defective insulin-mediated glucose transport in skeletal muscle is a major contributor to the pathogenesis of insulin-resistant states such as obesity and type 2 diabetes (7). Insulin stimulates glucose transport by activating a cascade of tyrosyl phosphorylation events initiated by binding of insulin to its receptor (6). The phosphorylated insulin receptor binds to and activates insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), resulting in activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway (35, 38), leading to increased glucose transport. In the insulin-signaling pathway, tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1 is a key step because it permits this docking protein to interact with signaling proteins that promote insulin action (2). Insulin stimulation of IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation is impaired in skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic subjects (5, 19, 21), providing evidence for a defect in IRS-1 that could contribute to impaired glucose transport and insulin resistance. Studies suggest that Rho-kinase (ROCK) is involved in the regulation of insulin signaling by interacting with IRS-1 in vitro (4, 8), and ROCK modulates insulin-mediated glucose metabolism in insulin-sensitive cultured cells (11). Although ROCK appears to be an important mediator of insulin action (11, 22), there are no data regarding the ability of insulin to activate ROCK1 in insulin target tissues in vivo in humans.

ROCK is a Ser/Thr protein kinase identified as a GTP-Rho-binding protein (27) and has two isoforms of Rho-kinase, ROCK1 (also known as ROKβ) (14, 28) and ROCK2 (also known as ROKα) (23, 28). ROCK is activated by binding with RhoA GTP through a Rho-binding domain (27) but is inhibited by interacting with RhoE GTP through a kinase domain (30). This suggests that the balance between RhoA and RhoE expression could be important in controlling ROCK activity. In isolated adipocytes, insulin stimulates Rho translocation to the membrane by a PI3K-dependent mechanism (16, 34). Our work also demonstrates that insulin activates Rho GTP activity in skeletal muscle of normal mice in vivo (11), suggesting that Rho signaling is involved in the insulin-signaling pathway.

Evidence suggests that activation of ROCK is required for insulin stimulation of glucose uptake in cultured cell lines (11). Inhibition of ROCK activity abrogates insulin-induced glucose transport and insulin signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and muscle cells (11). The possibility that ROCK could play an important role in insulin resistance in vivo is supported by a study showing that global ROCK1-deficient mice (ROCK1−/−) are insulin resistant, which is caused by impairing insulin signaling in skeletal muscle (22). Moreover, our study with normal mice demonstrates that acute treatment with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 leads to insulin resistance in vivo by reducing insulin-mediated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (11). Together, it would be of great interest to know that reduced activation of ROCK1 could play an important role in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in humans. However, the levels of Rho proteins and activities of ROCK1 in skeletal muscle of human insulin-resistant states have not been investigated.

In the current study, to determine the mechanism(s) for insulin resistance in obese nondiabetic and type 2 diabetic subjects, we investigated the ability of insulin to stimulate ROCK1 activity in skeletal muscle. Here we show that in vivo administration of insulin activates ROCK1 in human skeletal muscle. The activity of ROCK1 is defective in muscle of insulin-resistant obese type 2 diabetic subjects concomitant with an ∼40% decrease in insulin-stimulated IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation. The impaired ROCK1 activity is closely associated with an upregulation in RhoE expression that may inhibit ROCK1 activity by increasing the binding to its kinase domain. Thus, our data suggest that a contributing factor involved in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance characterized by impaired insulin action on glucose uptake could be dysregulation of ROCK1 in skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects.

Ten lean nondiabetic subjects, 10 obese nondiabetic subjects, and 10 obese subjects with type 2 diabetes participated in this study. There were three females in the lean group, three females in the obese group, and five females in the diabetic group. There was no difference in the insulin action parameters when the female subjects were excluded from the analyses, so we included them. The experimental protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Investigation of the University of California San Diego. Informed written consent was obtained after explanation of the protocol. All nondiabetic subjects had normal glucose tolerance (75-g oral glucose load) as defined by fasting glucose <126 mg/dl and 2 h glucose <140 mg/dl (1). All subjects were screened to ensure they were healthy, except for diabetes, and did not have significant diabetic complications. Hypoglycemic agents were withdrawn ≥2 wk before studies were performed. No subject was on any other medication known to affect carbohydrate metabolism.

Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp.

All subjects were admitted to the Special Diagnostic and Treatment Unit at the Veterans Medical Center San Diego and consumed a weight maintenance standardized diet containing 55% of calories as carbohydrate, 30% as fat, and 15% as protein for ≥24 h before the studies. After an overnight fast, they underwent a 3-h hyperinsulinemic (300 mU·m2·min−1) euglycemic (5.0–5.5 mM) clamp (20). The glucose disposal rate (GDR) was determined during the last 30 min of the clamp. Percutaneous needle biopsies of vastus lateralis muscle were performed prior to insulin infusion and at the end of the clamp (20), and muscle tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Plasma glucose and insulin levels were determined before each biopsy.

Preparation of muscle lysates.

Muscle tissue (50 mg) was homogenized using a polytron at half-maximum speed for 1 min on ice in 500 μl of buffer A (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 100 mM NaF, and 2 mM Na3VO4) containing 1% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. Muscle lysates were solubilized by continuous stirring for 1 h at 4°C and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 g. The supernatants were stored at −80°C until analysis.

ROCK1 activity.

Muscle lysates (300 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoprecipitation for 4 h with 10 μl of a polyclonal ROCK1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) coupled to protein G-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia Biotechnology). Immune pellets were washed and resuspended in 50 μl of a kinase mixture {20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM DTT, 100 μM ATP, 1 mM EDTA, 1 μM microcystin-LR, 1 μg myosin phosphatase-targeting subunit-1 (MYPT-1) substrate protein (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and 1 μCi [γ-32P]ATP} and incubated at 30°C for 30 min (9). Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was dried and quantitated using a PhosphorImager (ImageQuant software; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and also exposed to film.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1.

Muscle lysate protein (500 μg of protein) was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with 5 μl of a polyoclonal anti-IRS-1 antibody (gift from Dr. Morris White, Children's Hospital, Boston, MA) coupled to protein A-sepharose. The immunoprecipitates were washed with buffer A and resuspended in 4× Laemmli sample buffer. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with a monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (PY-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or a polyclonal anti-phospho-Ser632/635 IRS-1 antibody (corresponding to human Ser636/639; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). The bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence and quantified by densitometry.

Immunoblotting analysis.

Muscle lysates (20–50 μg of protein) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated with polyclonal antibodies against ROCK1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cofilin (Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-Ser3 cofilin (Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-Ser333 ezrin (Cell Signaling Technology), or monoclonal antibodies specific for RhoA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and RhoE (Millipore). The membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (Amersham). The bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence and quantified by densitometry.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses, including correlation coefficients, were performed using the Stat View program (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). Statistical significance was tested with analysis of variance.

RESULTS

Clinical and metabolic characteristics of the subjects.

Body mass index (BMI) was increased in obese nondiabetic and obese type 2 diabetic subjects compared with lean subjects (Table 1). BMI was not different between obese nondiabetic and diabetic subjects. Fasting serum glucose and hemoglobin A1c were normal in obese nondiabetic subjects but elevated in type 2 diabetic subjects (Table 1). Fasting plasma insulin levels tended to be increased in obese nondiabetic subjects and were 2.5-fold elevated in diabetic subjects compared with lean subjects (Table 1). Fasting plasma free fatty acid levels were normal in obese nondiabetic subjects but were elevated in diabetic subjects (Table 1). GDR was reduced 38% in obese nondiabetic subjects compared with lean, 62% in obese diabetic subjects compared with lean, and 39% in obese diabetic compared with obese nondiabetic subjects (Table 1). Thus, obese nondiabetic subjects were mildly insulin resistant, whereas diabetic subjects were more severely insulin resistant.

Table 1.

Clinical and metabolic characteristics of lean, obese, and diabetic subjects

| Lean | Obese | Diabetic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 37.3 ± 3.2 | 42.8 ± 3.3 | 47.6 ± 3.6 |

| Body mass index‡ | 22.7 ± 0.8 | 33.9 ± 1.2§ | 36.0 ± 1.5§ |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.5§¶ |

| Glucose, mM | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.3§¶ |

| Insulin, pM | 62.7 ± 17.1 | 100.8 ± 13.3 | 151.7 ± 29.8† |

| Free fatty acids, mM | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.67 ± 0.06§¶ |

| GDR, mg·kg−1·min−1 | 12.4 ± 0.8 | 7.6 ± 0.5§ | 4.6 ± 0.6§¶ |

Values are means ± SE. GDR, glucose disposal rate. No. of subjects: lean = 10 (7 male, 3 female), obese = 10 (7 male, 3 female), and obese type 2 diabetic = 10 (5 male, 5 female). Glucose, hemoglobin A1c, insulin, and free fatty acids were measured after an overnight fast. GDR was measured by the hyperinsulinemic (300 mU·m2·min−1) euglycemic (5.0–5.5 mM) clamp.

Body mass index was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Statistical significance of P < 0.05 vs. lean.

Statistical significance of P < 0.01 vs. lean.

Statistical significance of P < 0.01 vs. obese.

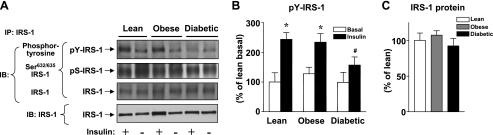

IRS-1 phosphorylation.

Figure 1A shows representative immunoblots of IRS-1 phosphorylation and protein in response to insulin administration in vivo. Figure 1, B and C, shows quantitation of results from multiple subjects. As expected, insulin increased IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation 2.4-fold in lean, 2.0-fold in obese nondiabetic, and only 1.5-fold in obese type 2 diabetic subjects. Insulin-induced IRS-1 phosphorylation was significantly decreased 41–48% in obese type 2 diabetic subjects compared with lean or obese nondiabetic subjects. However, 3 h of insulin infusion did not stimulate IRS-1 Ser632/635 phosphorylation in the skeletal muscle of human subjects, and this phosphorylation was not different among the groups (Fig. 1A). The total amounts of IRS-1 proteins were unaltered among three groups (Fig. 1A). These data are also consistent with the previous findings (5, 19, 21).

Fig. 1.

Insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) tyrosine phosphorylation and IRS-1 protein levels in skeletal muscle of lean, obese nondiabetic, and obese diabetic subjects. All subjects underwent a 3-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, and biopsies of vastus lateralis muscle were performed before and at the end of the clamp. A: muscle lysates (300–500 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an IRS-1 antibody. The precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody or anti-phospho-Ser632/635 IRS-1 antibody or an IRS-1 antibody. Note that the IRS-1 antibody reacts more strongly with the phosphorylated form of IRS-1 protein. Muscle lysates (50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. IRS-1 was visualized by immunoblotting (IB). The immunoblots shown are representative of 3 blots. B: bars show densitometric quantitation of IRS-1 phosphorylation from lean, obese, and obese type 2 diabetic subjects. Results are means ± SE for 9–10 subjects/group. *P < 0.01 vs. basal state; #P < 0.05 vs. lean or obese. C: bars show densitometric quantitation of IRS-1 protein levels from lean, obese, and obese type 2 diabetic subjects. The IRS-1 protein levels in the basal state are only quantitated. Results are means ± SE for 9–10 subjects/group.

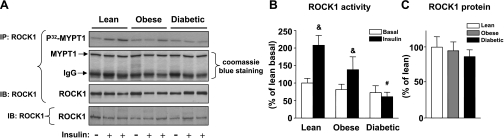

ROCK1 activity and protein.

Figure 2A shows representative autoradiograms in which MYPT-1 phosphorylation is the index of ROCK1 activity assessed by the immune complex assay (11). The samples from a given subject biopsied in the basal and insulin-stimulated states are run on adjacent lanes. No variation in amount of MYPT-1 substrate was detected in each lane, indicating that the assay was carefully performed without loss of samples during multistep procedures. Figure 2B shows quantitation of results from many subjects. Basal activity of ROCK1 in skeletal muscle was not different among the three groups (Fig. 2B). Insulin increased ROCK1 activity 2.1-fold in lean and 1.7-fold in obese nondiabetic subjects in skeletal muscle. However, ROCK1 activity did not increase in response to insulin in skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic subjects (Fig. 2B). The amounts of ROCK1 protein in skeletal muscle were unchanged in these subjects (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Rho-kinase 1 (ROCK1) activity and ROCK1 protein amounts in skeletal muscle of lean, obese nondiabetic, and obese diabetic subjects. Subjects underwent clamp and biopsies as in Fig. 1. A: ROCK1 activity was measured in muscle lysates (300 μg) that were subjected to IP with a ROCK1 antibody. The immunoprecipitated pellets were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gel. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue, dried, and exposed to film. The gel was also transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and quantitated using a PhosphorImager. ROCK1 was visualized by IB. Muscle lysates (50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. ROCK1 was visualized by IB. The immunoblots shown are representative of 3 blots. B: bars show quantitation of ROCK1 activity from lean, obese, and obese type 2 diabetic subjects. Results are means ± SE for 8–9 subjects/group. &P < 0.05 vs. lean or obese for basal condition; #P < 0.05 vs. lean for insulin-stimulated condition. C: bars show densitometric quantitation of ROCK1 protein levels from lean, obese, and obese type 2 diabetic subjects. The ROCK1 protein levels in the basal state are only quantitated. Results are means ± SE for 9–10 subjects/group.

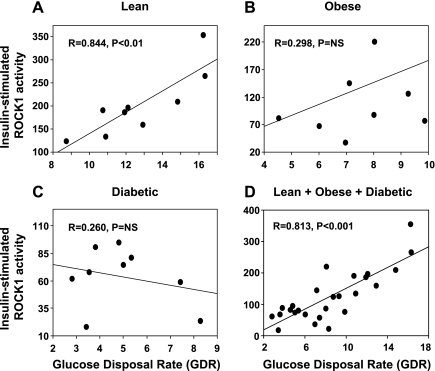

Relationship between ROCK1 activity and GDR.

A highly significant positive relationship was seen between insulin-stimulated ROCK1 activity and insulin-stimulated GDR in lean subjects (r = 0.844, P < 0.01) and in all subjects (r = 0.813, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3, A and D). This correlation was not present in obese nondiabetic (Fig. 3B) or obese type 2 diabetic subjects (Fig. 3C). Neither the absolute level of insulin-stimulated ROCK1 activity nor the increment in insulin-stimulated activity above basal correlates with fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, fasting plasma insulin, or BMI (not shown). These data suggest that the resistance to insulin-stimulated glucose disposal may involve a defect of ROCK1 activation.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between insulin-stimulated ROCK1 activity and glucose disposal rate (GDR) in skeletal muscle of humans undergoing euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp. Correlation between insulin-stimulated ROCK1 activity and GDR in lean (

A), obese (B), and diabetic subjects (C) and the sum of lean, obese, and diabetic subjects (D). Each circle represents data from 1 subject. NS, not significant.

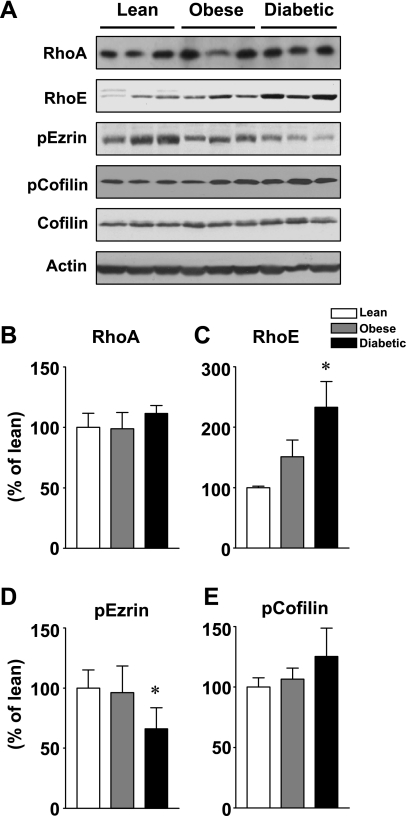

RhoA and RhoE protein levels and ezrin and cofilin phosphorylation.

Figure 4A shows representative immunoblots of RhoA and RhoE protein and ezrin and cofilin phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of human insulin-resistant subjects. Figure 4, B–E, shows quantitation of results from multiple subjects. RhoA and RhoE, both of which are members of the small G protein family, are upstream effecters of ROCK1 (32, 37). The total amounts of RhoA protein were similar among three groups (Fig. 4B). However, the levels of RhoE protein in skeletal muscle were significantly increased in obese type 2 diabetic subjects (P < 0.01) and tended to be increased in obese nondiabetic subjects (P < 0.07) compared with lean subjects (Fig. 4C). Ezrin protein is involved in the regulation of actin filament and is also phosphorylated by ROCK (26). In skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic subjects, the phosphorylation of ezrin was decreased by 45% over lean or obese subjects (Fig. 4D). However, the phosphorylation of cofilin, a downstream mediator of the ROCK1 pathway, was unaltered by obesity or type 2 diabetes (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these data showing that all downstream pathways in ROCK1 signaling are not similarly affected could be important for understanding the pathogenesis of the insulin resistance of type 2 diabetes.

Fig. 4.

RhoA and RhoE protein amounts and ezrin and cofilin phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of lean, obese, nondiabetic, and obese diabetic subjects. A: proteins in muscle lysates (50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. RhoA, RhoE, ezrin, and cofilin were visualized by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. This blot is representative of 3 blots. B–E: bars show densitometric quantitation of RhoA, RhoE, phosphorylated ezrin (p-ezrin), and p-cofilin levels from lean, obese, and obese type 2 diabetic subjects. Results are means ± SE for 8–10 subjects/group. *P < 0.01 vs. lean.

DISCUSSION

ROCK isoforms have been shown to participate in insulin signaling and glucose metabolism in cultured cell lines (4, 8, 11). Our recent work revealed that deficiency of ROCK1 causes systemic insulin resistance by impairing insulin signaling in skeletal muscle in vivo (22), and inhibition of ROCK decreases insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and insulin signaling in adipocytes and muscles cells in vitro (11). In the present study, we investigated the possibility that impaired activation of ROCK1 contributes to the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic humans. To our knowledge, our current data are the first to demonstrate that in vivo insulin administration in humans activates ROCK1 in skeletal muscle, and the ability of insulin to activate ROCK1 in vivo in skeletal muscle of obese humans with type 2 diabetes is significantly impaired. Importantly, the correlation between insulin-stimulated ROCK1 activity and glucose disposal rate in lean subjects is not found in obese or type 2 diabetic subjects. These data, combined with our previous findings, suggest that, in human muscle, alterations in ROCK1 activation are likely to contribute to the insulin resistance of type 2 diabetes and further highlight the important role of ROCK1 in the metabolic action of insulin in vivo.

A number of studies have demonstrated that ROCK is activated in the aorta of Zucker obese rats (39), the renal cortex of Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty insulin-resistant rats (18), and penile tissue, the bladder, and the heart of streptozotocin-induced diabetes (24) as well as blood leukocytes in Taiwanese with metabolic syndrome (25). However, the current data demonstrate that ROCK1 activity by insulin is significantly diminished in skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic subjects compared with lean or obese nondiabetic subjects. Although these differential effects of ROCK on several tissues are unclear at this time, it is conceivable that they could be explained in part by tissue-specific regulation of ROCK. In fact, previous studies were not performed in classic insulin target tissues such as skeletal muscle, adipose tissues, and liver (13, 18, 24, 25, 39).

Of note, chronic hyperglycemia and/or hyperinsulinemia can lead to the development of insulin resistance, which results from the downregulation of glucose transport as well as alteration of insulin signaling in peripheral tissues (10, 15, 29, 33, 40). Possibly, a defect in ROCK1 activity in obese type 2 diabetic humans may be secondary to the effects of hyperglycemia and/or hyperinsulinemia in this insulin-resistant state. In our obese subjects, insulin-stimulated ROCK1 activity tended to be decreased in skeletal muscle compared with lean subjects. In this regard, it is likely that reduced glucose disposal rate in obese nondiabetic subjects may not be sufficient to decrease ROCK1 signaling. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that obese nondiabetic subjects with more severe insulin resistance would also have impaired ROCK1 activity.

RhoA is a major upstream mediator of ROCK1 and activates the catalytic activity of ROCK1 by binding to a Rho-binding domain (3, 36). In contrast, RhoE binds to the kinase domain of ROCK1, thereby inhibiting its activity (30), indicating that RhoE may represent an endogenous inhibitor of ROCK1. Based on the similarity of RhoE and RhoA protein sequences, it has been suggested that RhoE may compete with RhoA for interaction with ROCK1 (30). In fact, RhoA and RhoE are not able to bind ROCK1 simultaneously (30). These observations led us to test the possibility that decreased ROCK1 activity in skeletal muscle of type 2 diabetic subjects is due to either decreased RhoA or increased RhoE levels. Interestingly, we found that RhoE expression is significantly increased in obese type 2 diabetic subjects compared with lean or obese subjects, whereas RhoA expression is normal. Our data suggest that the mechanism responsible for reduced ROCK activation is that upregulation of RhoE could lead to an increase in physical interaction with ROCK1 through the kinase domain of ROCK1 by competing with RhoA. Thus, RhoE is more likely than RhoA to play a role in the insulin resistance that is seen in type 2 diabetes.

Given that the key function of RhoE GTPase is induction of the loss of actin stress fibers (31), it is also possible that increased RhoE levels in skeletal muscle may change the formation of actin filaments, which could contribute to dysregulation of GLUT4 vesicle trafficking and glucose transport mediated by insulin. Therefore, it is likely that increased RhoE GTPase per se may also play an important role in insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes in vivo. In this regard, studies with epitrochlearis muscles demonstrated that cortical F-actin was reduced in insulin-resistant obese Zucker rats compared with insulin-sensitive lean littermates, providing evidence that the abnormality of cytoskeletal reorganization could contribute to this insulin-resistant state (12). Future studies are needed to determine the physiological role of RhoE in the regulation of insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis.

Our studies have demonstrated that ROCK regulates the metabolic action of insulin by phosphorylating IRS-1 serine residues at 632/635, 936, and 972, which can positively modulate IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation and PI3K activity (11). Consistent with previous findings (5, 19, 21), our data also revealed that IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation is significantly impaired in obese type 2 diabetic subjects compared with lean or obese nondiabetic subjects. However, under our experimental conditions of 3-h insulin infusion, we were unable to see insulin stimulation of IRS-1 Ser632/635 phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of human muscle. This could be due to either the duration of insulin stimulation or the insensitivity of phosphospecific IRS-1 antibody for human muscle. In fact, in diet-induced obese mice, IRS-1 Ser632/635 phosphorylation in skeletal muscle is decreased in 15–30 min after insulin stimulation (17). It is also possible that, in human skeletal muscle, IRS-1 serine sites such as 936 and 972 but not 632/635 may play an important role in the regulation of ROCK1-mediated glucose metabolism. Nevertheless, the current data suggest that defective ROCK1 activity may cause impaired IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation via diminishing IRS-1 serine phosphorylation (possibly 936 or 972), which would be predicted to favor a lower ability of IRS-1 to activate PI3K, leading to reduced glucose utilization in type 2 diabetic subjects.

In conclusion, in vivo administration of insulin stimulates ROCK1 activity in human skeletal muscle. In insulin-resistant obese subjects with type 2 diabetes and with the characteristic impairments in glucose disposal in skeletal muscle, insulin-stimulated ROCK1 activity is reduced without changes in ROCK1 protein content. Interestingly, RhoE GTPase that inhibits the catalytic activity of ROCK1 by binding to the kinase domain of the enzyme is upregulated in these subjects. Thus, defective ROCK1 activity due to increased RhoE expression may be an important factor in insulin resistance in skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic humans. The emergence of ROCK1 as a potentially important step in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance could lead to new treatment approaches for obesity and type 2 diabetes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (5R21-DK-075943 and 1-R01-DK-083567-1A1 to Y. B. Kim), the American Diabetes Association (1-09-RA-87 to Y. B. Kim), the Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and VA San Diego Healthcare System (to R. R. Henry), and the General Clinical Research Branch, Division of Research Resources (M01-RR-00827).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. No authors listed Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 21, Suppl 1: S5–S22, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aguirre V, Werner ED, Giraud J, Lee YH, Shoelson SE, White MF. Phosphorylation of Ser307 in insulin receptor substrate-1 blocks interactions with the insulin receptor and inhibits insulin action. J Biol Chem 277: 1531–1537, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amano M, Fukata Y, Kaibuchi K. Regulation and functions of Rho-associated kinase. Exp Cell Res 261: 44–51, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Begum N, Sandu OA, Ito M, Lohmann SM, Smolenski A. Active Rho kinase (ROK-alpha) associates with insulin receptor substrate-1 and inhibits insulin signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 277: 6214–6222, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Björnholm M, Kawano Y, Lehtihet M, Zierath JR. Insulin receptor substrate-1 phosphorylation and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in skeletal muscle from NIDDM subjects after in vivo insulin stimulation. Diabetes 46: 524–527, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheatham B, Kahn CR. Insulin action and the insuliln signaling network. Endocr Rev 16: 117–142, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes: metabolic and molecular implications for identifying diabetes. Diabetes Rev 5: 177–269, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farah S, Agazie Y, Ohan N, Ngsee JK, Liu XJ. A rho-associated protein kinase, ROKalpha, binds insulin receptor substrate-1 and modulates insulin signaling. J Biol Chem 273: 4740–4746, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feng J, Ito M, Kureishi Y, Ichikawa K, Amano M, Isaka N, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K, Hartshorne DJ, Nakano T. Rho-associated kinase of chicken gizzard smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 274: 3744–3752, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Folli F, Saad MJ, Backer JM, Kahn CR. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in liver and muscle of animal models of insulin-resistant and insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 92: 1787–1794, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Furukawa N, Ongusaha P, Jahng WJ, Araki K, Choi CS, Kim HJ, Lee YH, Kaibuchi K, Kahn BB, Masuzaki H, Kim JK, Lee SW, Kim YB. Role of Rho-kinase in regulation of insulin action and glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab 2: 119–129, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horvath EM, Tackett L, McCarthy AM, Raman P, Brozinick JT, Elmendorf JS. Antidiabetogenic effects of chromium mitigate hyperinsulinemia-induced cellular insulin resistance via correction of plasma membrane cholesterol imbalance. Mol Endocrinol 22: 937–950, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13. Hu E, Lee D. Rho kinase as potential therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases: opportunities and challenges. Expert Opin Ther Targets 9: 715–736, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ishizaki T, Maekawa M, Fujisawa K, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Fujita A, Watanabe N, Saito Y, Kakizuka A, Morii N, Narumiya S. The small GTP-binding protein Rho binds to and activates a 160 kDa Ser/Thr protein kinase homologous to myotonic dystrophy kinase. EMBO J 15: 1885–1893, 1996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kahn BB, Shulman GI, DeFronzo RA, Cushman SW, Rossetti L. Normalization of blood glucose in diabetic rats with phlorizin treatment reverses insulin-resistant glucose transport in adipose cells without restoring glucose transporter gene expression. J Clin Invest 87: 561–570, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Karnam P, Standaert ML, Galloway L, Farese RV. Activation and translocation of Rho (and ADP ribosylation factor) by insulin in rat adipocytes. Apparent involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem 272: 6136–6140, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khamzina L, Veilleux A, Bergeron S, Marette A. Increased activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in liver and skeletal muscle of obese rats: possible involvement in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Endocrinology 146: 1473–1481, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kikuchi Y, Yamada M, Imakiire T, Kushiyama T, Higashi K, Hyodo N, Yamamoto K, Oda T, Suzuki S, Miura S. A Rho-kinase inhibitor, fasudil, prevents development of diabetes and nephropathy in insulin-resistant diabetic rats. J Endocrinol 192: 595–603, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim YB, Kotani K, Ciaraldi TP, Henry RR, Kahn BB. Insulin-stimulated protein kinase C lambda/zeta activity is reduced in skeletal muscle of humans with obesity and type 2 diabetes: reversal with weight reduction. Diabetes 52: 1935–1942, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim YB, Nikoulina SE, Ciaraldi TP, Henry RR, Kahn BB. Normal insulin-dependent activation of Akt/protein kinase B, with diminished activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase, in muscle in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 104: 733–741, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krook A, Björnholm M, Galuska D, Jiang XJ, Fahlman R, Myers MG, Jr, Wallberg-Henriksson H, Zierath JR. Characterization of signal transduction and glucose transport in skeletal muscle from type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 49: 284–292, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee DH, Shi J, Jeoung NH, Kim MS, Zabolotny JM, Lee SW, White MF, Wei L, Kim YB. Targeted disruption of ROCK1 causes insulin resistance in vivo. J Biol Chem 284: 11776–11780, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leung T, Manser E, Tan L, Lim L. A novel serine/threonine kinase binding the Ras-related RhoA GTPase which translocates the kinase to peripheral membranes. J Biol Chem 270: 29051–29054, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin G, Craig GP, Zhang L, Yuen VG, Allard M, McNeill JH, MacLeod KM. Acute inhibition of Rho-kinase improves cardiac contractile function in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Res 75: 51–58, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu PY, Chen JH, Lin LJ, Liao JK. Increased Rho kinase activity in a Taiwanese population with metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 1619–1624, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsui T, Maeda M, Doi Y, Yonemura S, Amano M, Kaibuchi K, Tsukita S. Rho-kinase phosphorylates COOH-terminal threonines of ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) proteins and regulates their head-to-tail association. J Cell Biol 140: 647–657, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mukai H, Toshimori M, Shibata H, Kitagawa M, Shimakawa M, Miyahara M, Sunakawa H, Ono Y. PKN associates and phosphorylates the head-rod domain of neurofilament protein. J Biol Chem 271: 9816–9822, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakagawa O, Fujisawa K, Ishizaki T, Saito Y, Nakao K, Narumiya S. ROCK-I and ROCK-II, two isoforms of Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein serine/threonine kinase in mice. FEBS Lett 392: 189–193, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pillay TS, Xiao S, Olefsky JM. Glucose-induced phosphorylation of the insulin receptor. Functional effects and characterization of phosphorylation sites. J Clin Invest 97: 613–620, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Riento K, Guasch RM, Garg R, Jin B, Ridley AJ. RhoE binds to ROCK I and inhibits downstream signaling. Mol Cell Biol 23: 4219–4229, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riento K, Ridley AJ. Rocks: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 446–456, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riento K, Villalonga P, Garg R, Ridley A. Function and regulation of RhoE. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 649–651, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saad MJ, Araki E, Miralpeix M, Rothenberg PL, White MF, Kahn CR. Regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 in liver and muscle of animal models of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 90: 1839–1849, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Standaert M, Bandyopadhyay G, Galloway L, Ono Y, Mukai H, Farese R. Comparative effects of GTPgammaS and insulin on the activation of Rho, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and protein kinase N in rat adipocytes. Relationship to glucose transport. J Biol Chem 273: 7470–7477, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 85–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Rho/Rho-kinase mediated signaling in physiology and pathophysiology. J Mol Med 80: 629–638, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wheeler AP, Ridley AJ. Why three Rho proteins? RhoA, RhoB, RhoC, and cell motility. Exp Cell Res 301: 43–49, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. White MF. IRS proteins and the common path to diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283: E413–E422, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wingard C, Fulton D, Husain S. Altered penile vascular reactivity and erection in the Zucker obese-diabetic rat. J Sex Med 4: 348–362; discussion 362–343, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yki-Jarvinen H, Helve E, Koivisto VA. Hyperglycemia decreases glucose uptake in type I diabetes. Diabetes 36: 892–896, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]