Abstract

Background and purpose

Internal fixation is a therapeutic mainstay for treatment of undisplaced femoral neck fractures and fractures without posterior comminution. The best treatment for unstable and comminuted fractures, however, remains controversial, especially in older patients. The present study was designed to assess the utility of the Intertan Nail® (IT) for stabilization of comminuted Pauwels type III fractures compared to dynamic hips screw (DHS).

Methods

Randomized on the basis of bone mineral density, 32 human femurs were assigned to four groups. Pauwels type III fractures were osteomized with a custom-made saw guide. In 16 specimens the posteromedial support was removed and all femurs were instrumented with an IT or a DHS. All constructs were tested with nondestructive axial loading to 700N, cyclical compression to 1,400N (10,000 cycles), and loading to failure. Outcome measures included number of survived cycles, mechanical stiffness, head displacement and load to failure.

Results

Postoperative mechanical stiffness and stiffness after cyclical loading were significantly reduced in all constructs regardless of the presence of a comminution defect (p = 0.02). Specimens stabilized with the IT had a lower construct displacement (IT, 8.5 ± 0.5 mm vs. DHS, 14.5 ± 2.2 mm; p = 0.007) and sustained higher failure loads (IT, 4929 ± 419 N vs. DHS, 3505 ± 453 N; p = 0.036) than the DHS constructs.

Interpretation

In comminuted Pauwels type III fractures, the fixation with the IT provided sufficient postoperative mechanical strength, comparable rate of femoral head displacement, and a similar tolerance of physiological loads compared to fractures without comminution. The absence of the posteromedial support in comminuted fractures tended to reduce the failure load regardless of the fixation method.

Introduction

The treatment of choice for intracapsular femoral fractures is currently under debate. The main goals of therapy are early mobilisation and rapid recovery of function. Most authors favour osteosynthesis for younger patients, undisplaced fractures, and fractures without posterior comminution [1, 2]. However, the best treatment for unstable fractures, particularly in older patients, remains controversial. Treating unstable femoral neck fractures with internal fixation is associated with various complications. In several reports, up to 36% of patients sustained screw cut-outs, loss of reduction, delayed unions or non-unions, and various deformities of the femoral neck [3]. Stability after internal fixation depends directly on the degree of fragmentation and/or compression of the posterior aspect of the femoral neck. In addition, osteosynthesis failure is highly correlated with osteoporosis [4, 5] and the amount of eccentric load in full weight bearing conditions [6, 7]. Moreover, osteosynthesis is more prone to failure when severe osteoporosis is associated with a displaced fracture. Although, in many biomechanical and clinical studies, these effects are recognised as important contributing factors to fixation failure, there is still room for improvement in the specific techniques of fracture management [8].

Of the several implants available, the dynamic hip screw (DHS) and multiple cannulated screws are currently considered standard for internal fixation of femoral neck fractures. To date, no osteosynthetic implant has been shown to provide superior stabilisation of osteoporotic femoral fractures [9]. In recent investigations, we performed internal fixation with an intramedullary nail with two integrated cephalocervical screws (Intertan® IT; Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN) that allowed intraoperatively-guided compression and rotational stability of the head/neck fragment [10]. In investigations primarily for the present study we noticed tendencies for a higher stiffness regarding the Intertan in femoral neck fractures without posterior comminution.

In this study, we compared the biomechanical strengths of the Intertan nail and DHS implants for internal fixation of unstable, osteoporotic femoral neck fractures with and without posterior comminution.

Materials and methods

Specimens

Thirty-two fresh human cadaveric femurs (13 female, 11 male), with no known history of hip pathology, were harvested at autopsy within the first two days post-mortem and frozen at -20°C. To exclude any metabolic diseases known to affect the skeleton, iliac crest biopsies were obtained during all autopsies. The patients had died in accidents or of acute disease, without any known long periods of immobilisation. The average age of the donors was 64 ± 3.4 years (range 31–89 years). The specimens were assigned to the four treatment groups with the aim of achieving similar mean bone mineral densities (BMD). The average BMD in all groups was below 0.9 g/cm2 (Table 1), measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA, DPX Bravo Due Prodigy). This level was chosen because the risk for osteoporosis increases with BMDs that fall below one standard deviation below the peak mean for young men (0.98 ± 0.12 g/cm2) or young women (0.92 ± 0.10 g/cm2) [11].

Table 1.

Demographic data and bone mineral densities (BMD)

| Group | IT | DHS | Com-IT | Com-DHS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 53.8 ± 6.3 | 67.3 ± 5.6 | 69.7 ± 9.9 | 68.0 ± 11.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1 ± 1.8 | 23.5 ± 1.3 | 23.5 ± 1.7 | 22.6 ± 0.5 |

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.86 ± 0.10 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | 0.83 ± 0.07 |

BMI body mass index, DHS dynamic hip screw, IT Intertan Nail®, com comminution

Group arrangement

Eight femurs without comminution were stabilised with an Intertan nail implant (IT group). A second group of eight femurs without comminution was fixed with a DHS implant (DHS group). Sixteen femurs that had comminution defects were pair-matched; of these, eight femurs were stabilised with an Intertan (Com-IT group), and eight femurs were stabilised with a DHS (Com-DHS group) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Group arrangement

| Group | N | Fracture | Comminution | Implant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | 8 | Pauwels III | − | Intertan |

| DHS | 8 | Pauwels III | − | DHS |

| Com-IT | 8a | Pauwels III | + | Intertan |

| Com-DHS | 8a | Pauwels III | + | DHS |

BMI body mass index, DHS dynamic hip screw, IT Intertan Nail®, com comminution

a Match paired

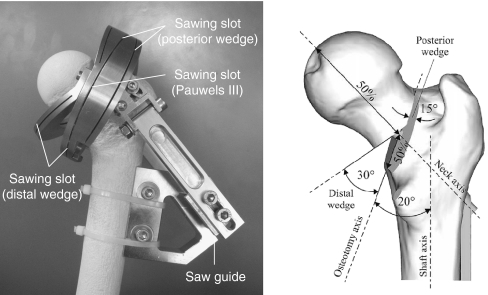

Sample preparation

To ensure consistency, one surgeon performed all specimen preparations and implant applications. After defrosting at room temperature, the femoral condyles were removed at 30 cm from the proximal tip of the greater trochanter. The distal 10 cm of the shaft were embedded in steel tubes with polyurethane (Ureol FC53; Gößl & Pfaff, Karlskron, Germany). To achieve bending moments in the sagittal and frontal planes and rotational moments under an axial load, we tilted the femur 10° lateral and 10° posterior with respect to the shaft axis [12]. During preparation, instrumentation, and biomechanical testing, the specimens were sprayed intermittently with normal saline to maintain hydration. To simulate a Pauwels type III fracture, all femurs were initially osteomised in the centre of the neck at a 20° angle with respect to the shaft axis. In the Com- groups, the comminution defect was created by removing two wedges: one distal wedge, cut at a 30° angle, and another posterior wedge, cut at a 15° angle, with respect to the initial osteotomy (Fig. 1). For all osteotomies, we used a custom-made saw guide, according to the protocol of Windolf et al. [13]. The fracture was anatomically reduced and stabilised with the different modalities (IT and DHS). The implant length was determined on an individual basis, and all osteosyntheses were performed under fluoroscopic guidance to ensure proper hardware position (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Custom-made saw guide and fracture geometry according to Windolf et al. [12]

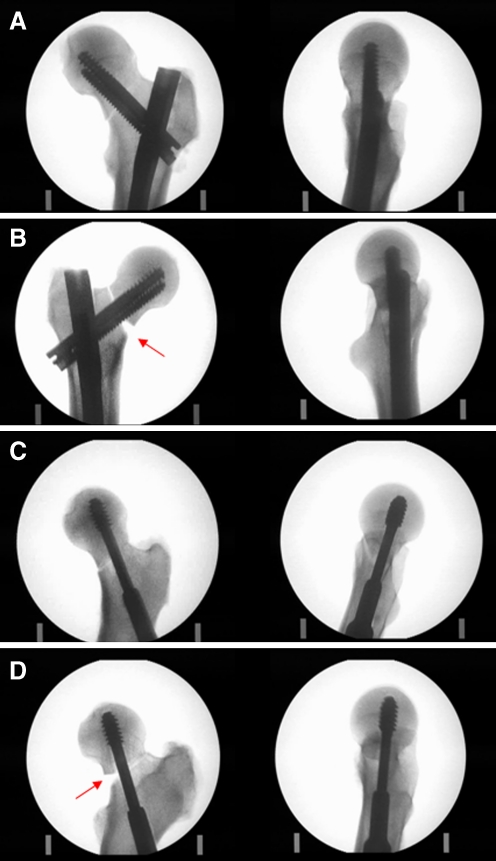

Fig. 2.

Postoperative radiographs in two planes (AP and axial) were obtained for each specimen after fixation, cyclical testing, and loading to failure to evaluate the position of the implant, the fracture dislocation, and the modes of specimen failure

Loading modalities

The specimens were placed in a servohydraulic testing machine (MTS 858.2, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) and loaded with an individually customised spherical shell. The distal embedded end of the femur was attached to a cardanic joint. The loading protocol was as follows:

Intact femurs: non-destructive axial load that increased to 700 N (10 cycles at 2 Hz); this provided control values for axial stiffness

Fractured and stabilised femurs: the same load (700 N, 10 cycles at 2 Hz)

Cyclical axial loading that increased to 1400 N (10,000 cycles at 2 Hz)

Femurs that withstood cyclical axial loading (III): a non-destructive axial load that increased to 700 N (10 cycles, 2 Hz)

Loading to failure at a constant speed of 4.6 mm/s

The initial load (I, II) represented the body weight of a 70 kg person; it was chosen to select the specimens that might withstand more destructive loading. After fracture fixation, the specimens were replaced in the axial loading configuration and cycled 10,000 times from 100 N to 1400 N at 2 Hz (III) with a load control. To prevent specimen displacement, the load valley was maintained at a constant 100 N throughout the experiment. The 1400 N load (III) represented the measured force on the hip in a 70 kg person standing on one leg [14]. The 10,000 cycles approximated the number of steps taken over a four- to six-week time period, the expected interval for fracture consolidation [15]. Femurs that withstood the cyclical testing (III) were retested for resistance to axial displacement (IV). All specimens that remained intact were finally loaded to failure (V). Failure was defined as a marked decrease in the applied load value, or an excess displacement of the actuator (<20 mm). Radiographs were obtained in two planes for each specimen after fixation (II), cyclical testing (III), and loading to failure (V).

Statistical analysis

Two-way analysis of variance was performed for group comparisons with age as a covariate. Group differences were checked for significance with a Tukey-B post-hoc comparison. For analysis of the failure frequency, a Chi² test was used. For comparisons of the force to failure, a t-test was used (unpaired for the IT and DHS groups, paired for the pair-matched femurs in the Com-group). The software package SPSS was used for statistical evaluations (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as mean and standard error (SER). The type I error probability was set to α = 0.05.

Results

Demographic data and mechanical stiffness

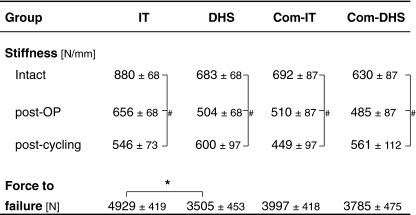

All groups were similar with respect to age, body mass index, and BMD (Table 1). Postfixation radiographs showed that all femurs received the proper hardware position and a near anatomic reduction with a <2 mm head–neck offset. The postoperative mechanical stiffness of the constructs was significantly reduced in all groups compared to that of the intact femurs (p = 0.02; Table 3). All instrumented constructs withstood the non-destructive load to 700 N (II). During cyclical testing (III), failures occurred in one construct from the IT group (cycle 2019), four from the DHS group (cycle 1575 ± 721), one from the Com IT group (cycle 1302), and two from the Com-DHS group (cycle 9672; cycle 48). Statistically, the failure frequency tended to be higher in the DHS group, but failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.152). The mechanical stiffness of the constructs after cyclic testing was similar to the post-operative situation and significantly reduced from the intact situation (p = 0.02) (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Mechanical stiffness

The postoperative and post-cyclical stiffness were reduced in all specimens (#p = 0.02)

The IT-constructs sustained higher failure loads than the DHS-constructs (*p = 0.036)

Fig. 3.

Regardless of the fixation method and the presence of the comminution defect, the postoperative and post-cyclical mechanical stiffness was significantly reduced compared to intact femurs (p = 0.02)

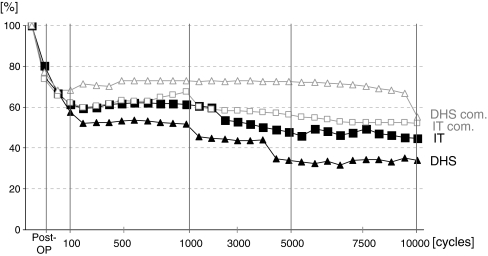

Construct displacement

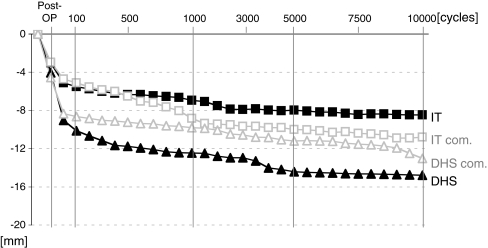

Independent of the fixation device used and fracture type (with or without comminution) all constructs sintered up to the 50th cycle and then set up to the 200th cycle. Due to sintering, at the end of cyclical loading, the construct displacement was significantly higher in the DHS group (14.5 ± 2.2 mm) compared to the IT group (8.5 ± 0.5 mm) (p = 0.007) (Fig. 4). The differences in construct displacement between DHS and Com-DHS, IT and Com-IT, and Com-IT and Com-DHS failed to reach statistical significance.

Fig. 4.

Independent of the fixation method, at 50 cycles, all of the constructs sintered. At the end of cyclical loading, the construct displacement was higher in the DHS groups compared to the IT groups (p = 0.007)

Force to failure

Eight specimens failed during cyclical testing. These tended to have lower BMDs (0.76 ± 0.05 g/cm2) than the femurs that withstood cyclical testing (0.85 ± 0.05 g/cm2; p = 0.149). Of the specimens that withstood cyclical testing, the IT constructs sustained significantly higher failure loads (IT group, 4929 ± 419 N) than the DHS constructs (DHS group, 3505 ± 453 N; p = 0.036). The fixation method did not influence the amount of force the femurs could withstand in the Com-groups (Com-IT, 3998 ± 418 N vs. Com-DHS, 3785 ± 822 N; p = 0.773). Femurs with a comminution defect tended to fail under a lower force (Com-IT + Com-DHS) than specimens without a comminution defect (IT + DHS), but the difference failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.175) (Table 3).

Discussion

The treatment of femoral neck fractures varies according to the patient’s age, activity level, fracture patterns, and bone quality. Approximately 20% of fractures are undisplaced [16]. The gold standard treatment for these fractures is anatomic reduction and internal fixation, most commonly with a DHS or multiple cannulated screws. For displaced femoral neck fractures, surgeons prefer a cannulated or dynamic hip screw for younger patients [2, 17, 18] and arthroplasty for older patients [19]. A number of controversies make it difficult to determine which treatments are optimal for patients between 60 and 80 years old or for active patients. Lu-Yao et al. demonstrated in a meta-analysis of 106 published reports that the mortality rate at 30 days after primary hemiarthroplasty tended to be higher than that after internal fixation [3]. However, the reoperation rate between one and two years ranged from 20 to 40% [5] after initial internal fixation and from 6 to 18% after primary arthroplasty [3]. Johannsson et al. observed a high dislocation rate after arthroplasty and low complications after initial osteosynthesis in patients with mental dysfunction. They concluded that, in patients with physical and mental deterioration, osteosynthesis may be more suitable than total arthroplasty [1]. In contrast, Bonnaire et al. postulated that one should aim for a primary endoprosthetic replacement in cases of dislocated intracapsular femoral neck fractures with any bone-dependent risk factors and a time delay between the accident and the reduction [8].

The stability after internal fixation depends directly on the degree of fragmentation and/or the compression on the posterior aspect of the femoral neck. This is of major interest because posterior comminution and/or large bony defects were observed in up to 70% of femur fractures [20]. Rotation of the fragments is an essential aspect of comminution defects and of osteosynthetic failure after internal fixation. Despite proper hardware placement, the gap resulting from a posterior comminution has the potential to close with posterior rotation of the femoral head. When a femoral neck fracture with a comminution defect is anatomically reduced, only the anterior portions of the head and neck fracture surfaces are brought into contact. Rau et al. concluded that a DHS alone was insufficient to control the proximal fragment and could lead to the loss of reduction and potential rotation during insertion of the lag screw. Moreover, he noticed that a device that allows fracture impaction might reduce the rate of delayed union or non-union [21]. Scheck recommended that a prosthetic replacement would be preferable in older individuals when a significant comminution was present in an unstable femoral neck fracture [22].

Based on these observations, it became essential to develop an intramedullary implant with a rotational safeguard for the head–neck fragment. The Intertan nail with two integrated cephalocervical screws was developed in 2005 for treating intertrochanteric fractures. This implant allowed linear intraoperative compression and rotational stability for the head/neck fragment. The results with this device were promising in intertrochanteric fractures [10]. Moreover, in previous studies of Pauwels III fractures without comminution, the Intertan showed less inferior head displacement, higher loads to failure, and longer survival under physiologic loads compared to the DHS and MCS. In the present study, the IT and DHS constructs showed similar femoral head displacement, with or without a comminution defect. This result might be due to the possibility that the cervical screws transferred the bending moments from the femoral head to the cortical bone of the femoral shaft. The significant differences between the IT and DHS groups might be explained by the fact that the antirotational screw of the IT was positioned closer to the inferior femoral neck than that of the DHS. Interestingly, the displacement of the IT and DHS constructs did not differ when there was a comminution defect. This might be due to the possibility that all the implants had set at the beginning of physiologic loading.

Comminuted fractures that lacked the posteromedial support tended to fail under smaller loads than those required for the failure of constructs without comminution defects. Thus, IT constructs without comminution sustained a 19% higher average load to failure than IT constructs with comminution. Given that the average patient incurs a load of 1400–1600 N on the hip joint during normal activities of daily living [12, 23], our results suggested that the Intertan nail could bear a patient’s full weight immediately postoperatively. Without a comminution defect, the IT constructs achieved an average load to failure one third higher than that of femurs stabilised with the DHS. The head–neck axis of 180° was restored with traction and internal rotation at the time of internal fixation. In the present study, 50% of the DHS constructs and 25% of the com-DHS constructs failed during cyclical loading. This could be due to the lack of control of the proximal fragment, which might be able to rotate during the insertion of the lag screw intraoperatively or during cyclical loading. In contrast to this, only one of the IT constructs and one of the com-IT constructs failed.

The present study was limited in statistical power due to the small number of samples tested. To simplify the experimental setup, we did not simulate muscle forces or craniocaudal loading. To simulate a single-leg stance, the femur was tilted in two different planes and a shear, force-free, vertical load was applied, according to Bergmann et al. [12].

Conclusions

Fixation with the Intertan nail provided sufficient postoperative mechanical stiffness, similar femoral head displacement, and similar tolerance of physiological loads in comminuted Pauwels III fractures compared to fractures without comminution defects. Independent of the fixation method (DHS or Intertan), the absence of the posteromedial bony support in comminuted fractures tended to reduce the load required to cause failure. In the future, in vivo studies will be required to determine the clinical outcome after Intertan nail fixation of comminuted femoral neck fractures and to explore the risks of delayed union, non-union, avascular head necrosis, and complicated prosthetic replacement after implant failure.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest and funding There is no conflict of interest and there was no funding.

References

- 1.Johansson T, Jacobsson SA, Iverson I, et al. Internal fixation versus total hip arthroplasty in the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures: a prospective randomized study of 100 hips. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:597–602. doi: 10.1080/000164700317362235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisler J, Cornwall R, Strauss E, et al. Outcomes of elderly patients with nondisplaced femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop. 2002;399:52–58. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu-Yao GL, Keller RB, Littenberg B, et al. Outcomes after displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis of one hundred and six published reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(1):15–25. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnaire FA, Buitrago-Tellez C, Schmal H, et al. Correlation of bone density and geometric parameter to mechanical strength of the femoral neck. Injury. 2002;33(Suppl 3):C47–C53. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjostedt A, Zetterberg C, Hansson T, et al. Bone mineral content and fixation strength of femoral neck fractures. A cadaver study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65(2):161–165. doi: 10.3109/17453679408995426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Audige L, Hanson B, Swiontkowski MF. Implant-related complications in the treatment of unstable intertrochanteric fractures: meta-analysis of dynamic screw versus dynamic screw-intramedullary nail devices. Int Orthop. 2003;27(4):197–203. doi: 10.1007/s00264-003-0457-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgaertner MR, Solberg BD. Awareness of tip-apex distance reduces failure of fixation of trochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(6):969–971. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B6.7949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnaire F, Zenker H, Lill Ch, et al. Treatment strategies for proximal femur fractures in osteoporotic patients. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker MJ. Evidence-based results depending on the implant used for stabilizing femoral neck fractures. Injury. 2002;33(Suppl 3):C15–C18. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruecker AH, Rupprecht M, Gruber M, et al. The treatment of intertrochanteric fractures: results using an intramedullary nail with integrated cephalocervical screws and linear compression. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23(1):22–30. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31819211b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sievänen H, Koskue V, Rauhio A, et al. Peripheral quantitative computed tomography in human long bones: evaluation of in vitro and in vivo precision. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(5):871–882. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergmann G, Deuretzbacher G, Heller M, et al. Hip contact forces and gait patterns from routine activities. J Biomech. 2001;34(7):859–871. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windolf M, Braunstein V, Dutoit C, et al. Is a helical shaped implant a superior alternative to the dynamic hip screw for unstable femoral neck fractures? A biomechanical investigation. Clin Biomech. 2009;24:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denham RA. Hip mechanics. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1959;41:550–557. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.41B3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubiak EN, Bong M, Park SS, et al. Intramedullary fixation of unstable intertrochanteric hip fractures: one or two lag screws. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(1):12–17. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conn KS, Parker MJ. Undisplaced intracapsular hip fracture: results of internal fixation in 375 patients. Clin Orthop. 2004;421:249–254. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000119459.00792.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heetveld MJ, Raaymakers ELFB, Walsum ADP, et al. Observer assessment of femoral neck radiographs after reduction and dynamic hip screw fixation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:160–165. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0780-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvan VT, Oakley MJ, Rangan A, et al. Optimum configuration of cannulated hip screws for the fixation of intracapsular hip fractures: a biomechanical study. Injury. 2004;35:136–141. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Tornetta P, 3rd, et al. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. An international survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):2122–2130. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyers MH, Harvey JP Jr, Moore TM (1974) The muscle pedicle bone graft in the treatment in displaced fractures of the femoral neck: Indications, operative technique, and results. Orthop Clin North Am 779–792 [PubMed]

- 21.Rau FD, Manoli A, 2nd, Morawa LG. Treatment of femoral neck fractures with the sliding compression screw. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;163:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheck M (1980) The significance of posterior comminution in femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 138–142 [PubMed]

- 23.Duda GN, Schneider E, Chao EYS. Internal forces and moments in the femur during walking. J Biomech. 1997;30:933–941. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(97)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]