Abstract

DNA polymerase β is essential for short-patch base excision repair. We have previously identified 20 somatic pol β mutations in prostate tumors, many of them missense. In the current paper we describe the effect of all of these somatic missense pol β mutations (p.K27N, p.E123K, p.E232K, p.P242R, p.E216K, p.M236L, and the triple mutant p.P261L/ T292A/ I298T) on the biochemical properties of the polymerase in vitro, following bacterial expression and purification of the respective enzymatic variants. We report that all missense somatic pol β mutations significantly affect enzyme function. Two of the pol β variants reduce catalytic efficiency, while the remaining five missense mutations alter the fidelity of DNA synthesis. Thus we conclude that a significant proportion (9 out of 26; 35%) of prostate cancer patients have functionally important somatic mutations of pol β. Many of these missense mutations are clonal in the tumors, and/or are associated with loss of heterozygosity and microsatellite instability. These results suggest that interfering with normal polymerase β function may be a frequent mechanism of prostate tumor progression. Furthermore, the availability of detailed structural information for pol β allows understanding of the potential mechanistic effects of these mutants on polymerase function.

Keywords: somatic, expression analysis, kinetic, POLB, mutation

INTRODUCTION

Human DNA polymerase β (pol β) is a monomeric protein of 335 residues, that is essential for short-patch base excision repair [Goodman, 2002]. Base excision repair (BER) is one of the major pathways of DNA repair that removes oxidized and alkylated bases from DNA [Friedberg, 2003]. Pol β is also involved in meiotic recombination [Kidane, 2010] and repair of double-stranded DNA breaks through the process of nonhomologous end joining [Wilson and Lieber, 1999]. Targeted disruption of pol β in mice resulted in neonatal lethality (due to respiratory failure) growth retardation and apoptotic cell death in the developing nervous system [Sugo et al., 2000], suggesting a role for pol β in neurogenesis.

The small size and monomeric nature of DNA polymerase β make it an attractive candidate for biochemical and kinetic analysis. Moreover, the availability of a high resolution crystal structure of polymerase β makes it easier to identify potential functionally important residues for mechanistic studies. In addition, polymerase β shares many structural and mechanistic features with other DNA polymerases of known structure: for example, the mechanism of DNA polymerization follows an ordered binding of substrates, with the DNA template binding first [Beard and Wilson, 1998]. These attributes make polymerase β a good candidate for biochemical analysis.

Pol β expression is increased in many cancer cells [Scanlon et al., 1989] and overexpression of pol β results in aneuploidy and tumorigenesis in nude immunodeficient mice [Bergoglio et al., 2002]. Moreover, pol β heterozygous (+/−) mice exhibit increased single-stranded DNA breaks, chromosomal aberrations and mutagenicity compared to normal animals [Cabelof et al., 2003]. Thus both higher and lower pol β activity can result in increased mutagenesis in vivo. Furthermore, several missense substitutions of pol β have also been shown to act as mutator mutants both in vivo and in vitro [Shah et al., 2001; Maitra et al., 2002].

Human DNA polymerase beta is ubiquitously expressed, and the POLB gene (MIM# 174760) is located at chromosome band 8p11, a chromosomal region known to be lost during prostate cancer progression [Visakorpi et al., 1995]. Somatic pol β mutations were initially found in two out of twelve Japanese prostate cancer patients [Dobashi et al., 1994], but that analysis was done by single strand conformation polymorphism, a technique that can miss mutations [Pearce et al., 2008].

We recently sequenced the complete coding region of the POLB gene for somatic mutations in 26 prostate cancer tissues. We identified 20 somatic mutations in these prostate tumors, nine of them missense [Makridakis et al., 2009]. With the exception of g.31911C>G (p.P242R), which substitutes the normal proline residue at position 242 with arginine, these substitutions were absent in lymphocyte DNA from the same patient. Many of the somatic mutations identified were prevalent in the tumors (i.e. they were present in more than half of the tumor chromosomes; Makridakis et al. [2009]) suggesting that they play an important role in tumor progression. Overall, 61% of the prostate cancer patients had somatic substitutions in pol β [Makridakis et al., 2009].

Molecular epidemiologic studies have shown that the p.P242R pol β substitution is significantly associated with decreased risk for colorectal cancer [Moreno et al., 2006]. However, the same substitution has also been associated with poorer lung cancer prognosis [Matakidou et al., 2007]. Functional biochemical studies may explain this discrepancy. In vitro, the p.P242R pol β substitution behaves as an anti-mutator [Hamid and Eckert, 2005], consistent with the colorectal cancer data.

Structural analyses may provide useful hints about the potential importance of some of the somatic prostate cancer mutations that we identified: Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of [methyl-13C] methionine–labeled pol β have shown that methionine-236 of pol β interacts with a single-nucleotide gapped DNA template (the natural pol β substrate), and that this interaction is essential for pol β conformational activation [Bose-Basu et al., 2004]. Both methionine-236 and threonine-292 are involved in DNA template binding [Bose-Basu et al., 2004; Sawaya et al., 1997] and thus may be important for function. Both the g.25314A4T (p.M236L) and the g.32573A4G (p.T292A) substitutions (found in prostate cancer patients; [Makridakis et al. 2009]) are predicted to destroy the hydrogen bond between these pol β residues and the DNA template [Sawaya et al., 1997]. Thus both of these mutations may result in loss of activity and/ or altered fidelity of DNA synthesis. Finally, proline-242 is in the “flexible loop”, a part of pol β that functions to position the primer and has been shown to contain several residues that cause a mutator phenotype when mutated [Dalal et al., 2004].

Even though we identified many somatic pol β mutations in prostate cancer, we do not know the functional effect of these mutations. In order to directly assess the potential role of the identified pol β mutations in prostate cancer progression, we biochemically characterized the effect of all the missense prostate cancer variants on both polymerase activity and fidelity of DNA replication, using mostly steady-state kinetic analysis. The data, presented here, demonstrate that these somatic pol β mutations may be important contributors to prostate cancer progression.

Furthermore, systematic biochemical characterization of the prostate cancer associated missense mutations of pol β, a monomeric polymerase highly suitable for mechanistic studies [Beard et al, 2002], provides valuable information on the molecular determinants of both polymerase activity and fidelity. In addition, the availability of detailed structural information for pol β allows structural-functional comparisons for all functionally important residues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nomenclature

The GenBank reference sequence accession number used for the genomic POLB sequence is AF491812.1.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The E. coli strain BL21 DE3 was used for polymerase β protein expression. E. coli DH5α, BL21 (DE3), and recombinant E. coli harboring human pol β variants were cultured in LB medium containing 25 µg/ml kanamycin (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) when appropriate.

Construction of variants of pol β

The distinct pol β mutants were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis using the Quick-change kit (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA) according to the protocol of the manufacturer using the pET28a(+)-WT (wild type) bacterial expression vector as a template (a gift of Dr. Joann Sweasy from Yale University). Successful mutagenesis was confirmed by DNA sequencing with BigDye chemistry on a 3100 ABI sequencer (PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA).

Expression and Purification of Mutant Enzymes

Purification of pol β proteins was performed as previously described [Kosa and Sweasy, 1999; An et al., 2004] with the following modifications. Each pol β variant was expressed as a fusion protein with a six-residue poly-histidine tag at the N terminus. The enzymes were purified using HisTrap FF crude Kit (GE Healthcare; Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer instructions. The fusion proteins were expressed in BL21 DE3 cells, which were grown at 37 °C to mid-log phase and then induced 3 to 6 hours with 1 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 40 mM Tris pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 100 µl Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) and lysed by sonication. Extracts were cleared by centrifugation (15,000 rpm, 15 min at 4 °C), and then loaded onto HisTrap FF crude Kit /100 ml of starting culture. The proteins were eluted with 500 mM imidazole in 0.5 M NaCl. Eluted proteins were then loaded onto a HiTrap SP HP column (GE Healthcare; Piscataway, NJ). The column was washed with 100 mM NaCl and proteins were eluted with 2 M NaCl and stored at −80 °C in 50 mM Tris pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 2 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors as above. Purified proteins were run on a Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel to assess purity. Protein levels were quantified by Bradford protein assay (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO).

Western bloting

Polymerase β proteins were identified by Western blot [Servant et al., 2002]. Proteins were electrophoresed in a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transfer to polyvinylidenedifluoride membrane (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA). Blots were blocked by 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (0.1% Tween) and incubated with anti-His tag antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. For detection we were used IR Dye 800CW Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (LI-COR Biosciences; Lincoln, NE) and the Odyssey apparatus (LI-COR Biosciences; Lincoln, NE).

Assay of DNA polymerase activity

DNA polymerase activity assay was performed by incorporation of [α-32P]dATP (PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA) as previously described [Maitra et al., 2002] with the following modifications. The final reaction mixture was 50 mM Tris buffer pH 8.0, 20 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 200 µg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 200 µM dithiothreitol, 20 µM dATP, 100 µM each of the three remaining dNTPs, 2 µCi of [α-32P]dATP, and 10 µg activated calf thymus DNA. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and stopped with EDTA. The reaction mixture were spotted on GFA filters (Whatman; Piscataway, NJ), which were washed twice with 22.5 mg/ml NaPPi, 8.5% concentrated perchloric acid and twice with 22.5 mg/ml NaPPi, 8% concentrated hydrochloric acid, and then washed in ethanol. The filters were dried and radioactivity was counted on a scintillation counter.

DNA Substrate

All oligonucleotides were synthesized and high pressure liquid chromatography-purified by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). A 20-mer (5’-GCA GGA AAG CGA GGG TAT CC-3’), a 46-mer (5’-TAT GGT ACG CTG GAC TTT GTG GGA TAC CCT CGC TTT CCT GCT CCT G-3’), and a 20-mer (5’-ACA AAG TCC AGC GTA CCA TA-3’) oligonucleotides were used as primer, template and down-stream oligonucleotide, respectively [Chagovetz et al., 1997]. 5’-32P end labeling of the 20-mer primer was performed with 3,000 Ci/mmol [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (U. S. Biochemical Corp.; Cleveland, OH) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The 32P-labeled primer was then purified from unincorporated label by a Microspin™ G-50 (GE Healthcare; Piscataway, NJ) column. The down-stream oligonucleotide was 5’-end phosphorylated by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The oligonucleotides were annealed at a primer: template: downstream oligonucleotide molar ratio of 1:1.2:1.3 in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, in order to create a single nucleotide gap. The mixture was incubated sequentially at 95 °C for 5 min, slow cooled to 50 °C for 30 min, and 50 °C for 20 min and then immediately transferred to ice. Annealing of primer was confirmed on an 18% polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bis-acrylamide: 29:1) native gel followed by autoradiography as described [Maitra et al., 2002; Li et al., 1999].

Steady-state incorporation experiments

All incorporation reactions (20 µl) were performed in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 20 mM NaCl, 0.2 mg/ml BSA, 2.5% glycerol and contained 50 nM annealed DNA substrate (see above). Correct incorporation (activity) reactions contained 2.5 nM purified Pol β enzymes except for the triple mutant (600 nM), while misincorporation (fidelity) reactions contained 2.5 nM to 300 nM purified Pol β enzymes. All concentrations given refer to the final concentrations after mixing. All reactions were performed by first preincubating the DNA substrate with Pol β for 3 min at 37 °C without the dNTPs. Reactions were initiated by the addition of a single dNTP (0.1–1400 µM). After 2 minutes incubation at 37 °C, the reactions were quenched by adding 20 µl of formamide loading buffer [formed by mixing 900 µl formamide, 22.2 µl 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0), and 77.8 µl water] and then boiled for 10 min, and immediately transferred into ice. Products were resolved on a 15% polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bis-acrylamide: 29:1) gel containing 7 M urea and then quantified by a Typhoon Trio+ Variable Mode PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare; Piscataway, NJ). To ensure that all reactions were conducted at steady state the enzyme concentrations were optimized using time course experiments [Chagovetz et al., 1997].

Kinetic Analysis

Kinetic data analyses were based on Lineweaver–Burk plots. We determined the values of kcat and Km,dNTP from trendline equations calculated from these plots by the Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft; Redmond, WA), using values obtained from the plotted kinetic data. The kcat/Km,dNTP values of mispairs were determined from dividing kcat and Km values obtained by Excel analysis of the inverse plots. Fidelity values for each dNTP were calculated using the following equation: Fidelity= [(kcat/Km,dNTP)correct + (kcat/Km,dNTP)incorrect]/(kcat/Km,dNTP)incorrect [Li et al., 1999]. Representative plots are shown in Supp. Figure S1.

Assay of DNA polymerase beta lyase activity

DNA polymerase β lyase activity assay was performed as in Prasad et al 1998, with the following modifications. Briefly, the HPLC purified DNA oligonucleotide (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) 49_lyase, was 3’ end labeled with [α-32P]dATP (PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA) by Terminal Transferase (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA). The sequence of 49_lyase is 5’ACTACAAATTAGAAAATAGCUGTCCTTGACGGCTAGAATTACCTACCGG3’, which contains a uracil at position 21 (underlined). The 50ul tailing reaction includes 50 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.9), 10 mM magnesium acetate, 0.25 mM CoCl2, 10 µCi of [α-32P]dATP and 5 pmoles of substrate DNA. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the labeled oligonucleotide was purified by Micro Bio-Spin chromatography Columns (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The complimentary strand of 49_lyase is RC49_lyase, whose sequence is 5’CCGGTAGGTAATTCTAGCCGTCAAGGACAGCTATTTTCTAATTTGTAGT3’, and has dATP at the uracil corresponding position. Following annealing of the forward and reverse strands, the AP site was created by removal of the uracil with Uracil DNA Glycosylase (UDG). The UDG reaction included 20mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 1mMEDTA, 1mM DTT, 18nM cold annealing substrate, 3×104cpm [α-32P] dATP labeled annealing substrate and 10 units of UDG (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA) in a 300 µl final volume. The UDG reaction was performed at 37°C for 30 min then stopped by phenol/chloroform extraction. Purified polymerase β variants were tested for their lyase activity. The reaction included 50 mM Hepes pH7.4, 2 mM DTT, 5mM MgCl2, with or without 0.2 units of apurinic endonuclease 1 (APE I) (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA). Final volume was 10 µl. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and stopped by addition of 10 µl 2X formamide loading buffer which contains 20mM EDTA and 95% formamide. Each assay was done in triplicate. After denaturing at 75 °C for 2 min, 10µl sample was loaded on to 15% polyacrylamide gel containing 7M urea. Electrophoresis was done at 75W for 80 min in 1x TBE buffer by Sequi-Gen GT Electrophoresis Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Gel drying and autoradiography were done as usual. Bands captured and quantified with software Image Quant 5.1. The lyase activity was calculated following kinetic analysis, as described above.

RESULTS

Expression constructs of Variants of DNA pol β

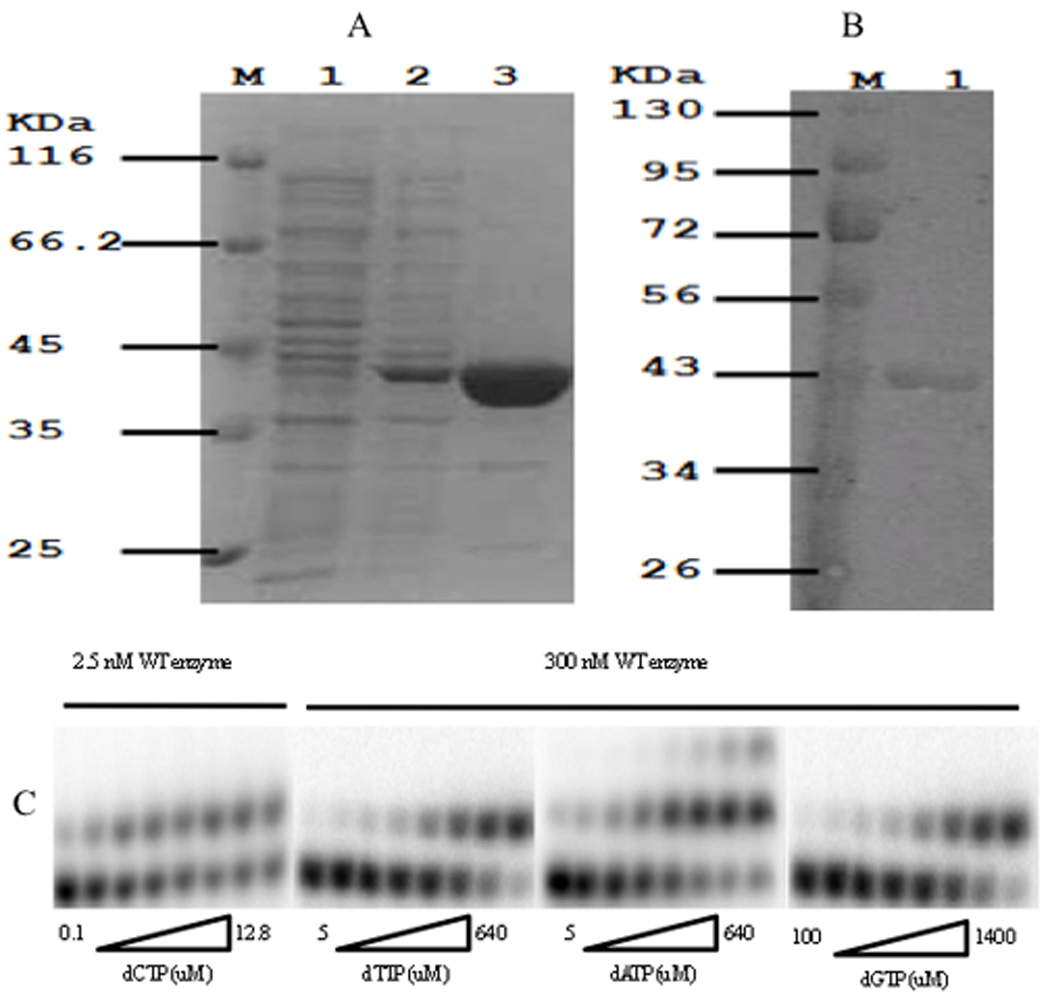

Somatic variants of DNA polymerase β originally found in prostate cancer tissue [Makridakis et al., 2009] were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis of the human pol β cDNA, as described in Experimental Procedures. Both normal (WT) and variants of pol β were expressed in E. coli and purified using column filtration techniques, as described in Experimental Procedures. After purification, WT and variants of DNA pol β were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. This analysis showed that we obtained > 90% pure versions of pol β for all variants except the triple mutant (for which we obtained 51% homogeneity; data not shown). Fig. 1 displays WT pol β protein analyzed on a coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel and detected by Western blot.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of purified pol β protein and gel assay of pol β single nucleotide insertion. A: Electrophoretic analysis of the expressed pol β protein at various stages of purification. Separation was performed on a 12.5% (W/V) SDS-polyacrylamide gel. M, marker; Lane 1, crude extract from BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells containing pET-28a(+)/ pol β ; Lane 2, crude extract from IPTG-induced BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells containing pET-28a(+)/ pol β ; Lane 3, purified pol β . B: Detection of purified protein by western bolt. M, marker; Lane 1, purified wild type pol β. C: A gapped oligo substrate was incubated with wild type pol β in increasing concentrations of a single dNTP as described under “Experimental Procedures”. Pol β concentrations was adjusted to optimize detection of primer extension products. dATP misincorporation resulted in a single nucleotide extension of the misinserted dATP (correct extension against the next nucleotide (dT) of the DNA substrate) but only at higher dATP concentrations.

Variants of DNA pol β have polymerase activity

We tested the polymerase activity of WT and variants of human DNA pol β by incorporating dNTPs into activated calf thymus DNA. These experiments showed that all variants of DNA pol β were active (data not shown).

Effect of DNA pol β variants on catalytic efficiency (correct incorporation)

To perform pol β kinetic analysis we employed a DNA substrate containing a single-nucleotide gap that was previously used for fidelity studies [Chagovetz et al., 1997; Roberts and Kunkel, 1996]. We determined pol β catalytic efficiency based on steady-state kinetic analyses of single-nucleotide addition (dCTP) opposite template dG on our single gapped DNA substrate. The catalytic activities (kcat) of both the WT and genetic variants of DNA pol β are listed in Table 1. This table shows that the catalytic activity of the g.15180G4A (p.E123K) variant was increased 63% compared to WT. Variants g.25302G4A (p.E232K), p.M236L, p.P242R, g.25254G4A (p.E216K), and g.1444G4C (p.K27N) exhibit similar catalytic activity to that of WT pol β.

TABLE 1.

Steady-state Kinetic Parameters for Correct Incorporation into a Gapped Oligo Substrate by Wild-type pol β and Variants*

| Enzyme | kcat, (s−1)a | Km, dCTP (uM) | kcat/Km dCTP(s−1M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 8.09 (±2.06) ×10−2 | 0.25 (±0.08) | 3.24 (±0.92) ×105 |

| p.K27N | 8.06 (±1.10) ×10−2 | 0.43 (±0.05) | 1.87 (±0.13) ×105 |

| p.E123K | 1.32 (±0.11) ×10−1 | 0.31 (±0.01) | 4.24 (±0.20) ×105 |

| p.E232K | 1.09 (±0.18) ×10−1 | 0.21 (±0.02) | 5.20 (±1.35) ×105 |

| p.P242R | 1.03 (±0.21) ×10−1 | 0.27 (±0.02) | 3.81 (±0.98) ×105 |

| p.E216K | 8.62 (±1.63) ×10−2 | 0.24 (±0.09) | 3.59 (±1.59) ×105 |

| p.M236L | 1.06 (±0.24) ×10−1 | 0.39 (±0.01) | 2.72 (±0.57) ×105 |

| Triple Mutant |

4.03 (±0.27) ×10−4 | 3.72 (±0.17) | 1.08 (±0.08) ×102 |

The results represent the mean of at least three independent determinations +/− standard error.

WT, wild-type.

Triple mutant= p.P261L/ p.T292A/ p.I298T.

Calculated using total protein concentration.

In comparing Km,dCTP between the specific variants and WT pol β (Table 1), we found that variants p.K27N and p.M236L increased the Km,dCTP 72% and 56%, respectively. Thus these variants of pol β have decreased affinity for the substrate. Other variants of pol β except the triple mutant (g.32481C4T (p.P261L)/ p.T292A/ g.32592T4C (p.I298T); Makridakis et al. [2009]) showed similar Km,dCTP to that of WT pol β.

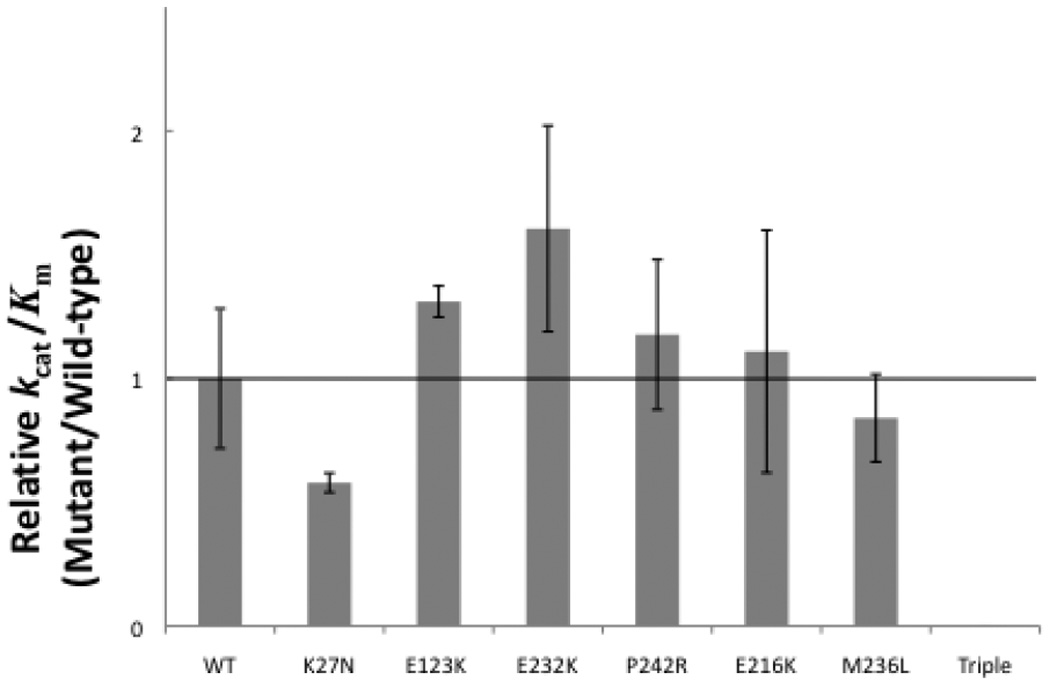

The best measure for assessing the potential effect of nucleotide variations on enzymatic activity in vivo is assaying catalytic efficiency. The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km,dCTP) of the p.K27N variant was decreased 42% compared to WT pol β in our assays. The remaining pol β variants, again with the exception of the triple mutant, displayed similar catalytic efficiency to that of WT pol β (Table 1, Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Influence of pol β variants on catalytic efficiency for dCTP insertion. WT and mutant variants were assayed on a single-nucleotide gapped DNA substrate with a templating dG, and the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km,dNTP) was determined from dividing kcat and Km values obtained by Excel analysis of the inverse plots. These data represent the mean of at least three independent determinations, +/− standard error.

Interestingly, the triple mutant pol β variant was significantly different than WT, or even the other variants (Table 1). The triple mutant variant showed a 99.5% decrease in catalytic activity compared with WT (Table 1). The Km,dCTP of the triple mutant was 15-fold higher than WT pol β and the catalytic efficiency kcat/Km,dCTP of the triple mutant was thus dramatically decreased (Table 1, Fig. 2) orders of magnitude lower than WT.

Effect of DNA pol β variants on fidelity (misincorporation)

Misincorporation studies were performed in odrer to understand the role of pol β variants on DNA synthesis fidelity. These experiments were performed with enzyme concentrations that were 120-fold higher than correct incorporation experiments for both variants and WT. Fig. 1C shows the results obtained for both correct and incorrect incorporation (misincorporation) experiments for the WT, with all four dNTPs.

Due to the low inherent activity of the triple pol β mutant we could not measure the catalytic activity for misincorporation even though we used more triple mutant enzyme and dNTPs (data not shown). The kcat, Km,dNTP, and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km,dCTP) values for misincorporation are reported in Table 2 for all variants. Percentage changes of the kcat, Km,dNTP, and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km,dCTP) were obtained from Table 2 and listed on Table 3. Variants p.K27N and p.E123K showed similar kcat to that of WT enzyme for dTTP, dATP, and dGTP misincorporations (Table 3). Variants p.P242R and p.E216K displayed decreased kcat for all dNTP misincorporations (Table 3). The p.E232K variant had similar kcat to WT enzyme for dATP and decreased kcat for dTTP and dATP misincorporations (Table 3). The p.M236L variant showed similar kcat for dTTP and dATP with the WT enzyme, and increased kcat for dGTP misincorporation compared to WT (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Steady-state Kinetic Parameters for Incorrect Incorporation into a Gapped Oligo Substrate by Wild-type pol β and Variants*

| Enzyme | kcat, (s−1)a | Km, dCTP (uM) | kcat/Km dNTP(s−1M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dG-dTTP | |||

| WT | 1.45 (±0.02) ×10−3 | 52.20 (±1.65) | 27.78 (±0.50) |

| p.K27N | 1.40 (±0.03) ×10−3 | 83.78 (±3.23) | 16.71 (±0.47) |

| p.E123K | 1.47 (±0.07) ×10−3 | 47.60 (±3.73) | 30.88 (±0.99) |

| p.E232K | 1.39 (±0.03) ×10−3 | 59.69 (±1.31) | 23.29 (±0.40) |

| p.P242R | 1.39 (±0.03) ×10−3 | 60.98 (±1.72) | 22.79 (±0.43) |

| p.E216K | 1.32 (±0.03) ×10−3 | 85.21 (±14.33) | 15.49 (±2.18) |

| p.M236L | 1.38 (±0.08) ×10−3 | 45.02 (±5.79) | 30.65 (±2.30) |

| dG-dATP | |||

| WT | 1.31 (±0.02) ×10−3 | 46.78 (±1.90) | 28 (±1.56) |

| p.K27N | 1.28 (±0.04) ×10−3 | 74.59 (±5.55) | 17.16 (±0.81) |

| p.E123K | 1.31 (±0.02) ×10−3 | 38.82 (±4.65) | 33.75 (±3.86) |

| p.E232K | 1.26 (±0.05) ×10−3 | 59.16 (±6.30) | 21.3 (±1.43) |

| p.P242R | 1.22 (±0.04) ×10−3 | 57.13 (±2.47) | 21.35 (±1.51) |

| p.E216K | 1.10 (±0.09) ×10−3 | 72.44 (±14.30) | 15.18 (±1.88) |

| p.M236L | 1.32 (±0.04) ×10−3 | 39.67 (±2.44) | 33.27 (±1.08) |

| dG-dGTP | |||

| WT | 9.78 (±0.20) ×10−4 | 446.41 (±15.77) | 2.19 (±0.08) |

| p.K27N | 8.82 (±1.84) ×10−4 | 767.89 (±256.68) | 1.15 (±0.13) |

| p.E123K | 9.99 (±0.60) ×10−4 | 457.59 (±47.18) | 2.18 (±0.11) |

| p.E232K | 7.35 (±0.95) ×10−4 | 322.91 (±104.29) | 2.28 (±0.42) |

| p.P242R | 7.98 (±0.15) ×10−4 | 430.51 (±23) | 1.85 (±0.09) |

| p.E216K | 8.29 (±0.54) ×10−4 | 748.76 (±88.86) | 1.11 (±0.07) |

| p.M236L | 1.16 (±0.04) ×10−3 | 478.25 (±48.46) | 2.43 (±0.21) |

The results represent the mean of at least three independent determinations +/− standard error.

WT, wild-type.

Calculated using total protein concentration.

TABLE 3.

Percentage Changes of kcat, Km, dNTP, and Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Km, dCTP) Compared to Wild-type

| Enzyme | kcat | Km, dNTP | kcat/Km dNTP |

|---|---|---|---|

| dG-dTTP | |||

| p.K27N | — | 60% (↑) | 40% (↓) |

| p.E123K | — | — | 11% (↑) |

| p.E232K | 4% (↓) | 14% (↑) | 16% (↓) |

| p.P242R | 4% (↓) | 17% (↑) | 18% (↓) |

| p.E216K | 9% (↓) | 33% (↑) | 44% (↓) |

| p.M236L | — | — | 10% (↑) |

| dG-dATP | |||

| p.K27N | — | 59% (↑) | 39% (↓) |

| p.E123K | — | 17% (↓) | 21% (↑) |

| p.E232K | — | 26% (↑) | 24% (↓) |

| p.P242R | 7% (↓) | 22% (↑) | 24% (↓) |

| p.E216K | 16% (↓) | 55% (↑) | 46% (↓) |

| p.M236L | — | 15% (↓) | 19% (↑) |

| dG-dATP | |||

| p.K27N | — | 72% (↑) | 47% (↓) |

| p.E123K | — | — | — |

| p.E232K | 25% (↓) | 28% (↓) | — |

| p.P242R | 18% (↓) | — | 16% (↓) |

| p.E216K | 15% (↓) | 68% (↑) | 49% (↓) |

| p.M236L | 19% (↑) | — | — |

—, not significantly different.

↑, significantly increased.

↓, significantly decreased.

The Km for dTTP misincorporation was increased for variants p.K27N, p.E216K, p.E232K, and p.P242R (Table 3). The Km of both p.E232K and p.P242R variants was increased for both dTTP and dATP misincorporations, but the Km for dGTP misincorporation was decreased only for the p.E232K variant, while the p.P242R variant showed Km similar to WT (Table 3). The p.E123K and p.M216L variants showed WT Km for dTTP and dGTP misincorporations and decreased Km for dATP misincorporations (Table 3).

In compared catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km,dNTP) for misincorporation, variants p.K27N, p.P242R, and p.E216K showed decreased efficiency for all misincorporations (Table 3). The p.E232K variant had decreased catalytic efficiency for both dTTP and dATP misincorporations but showed WT efficiency for dGTP misincorporation (Table 3). The kcat/Km,dNTP of p.E123K and p.M236L variants was increased for dTTP and dATP misincorporations but was similar to WT enzyme for dGTP misincorporation (Table 3).

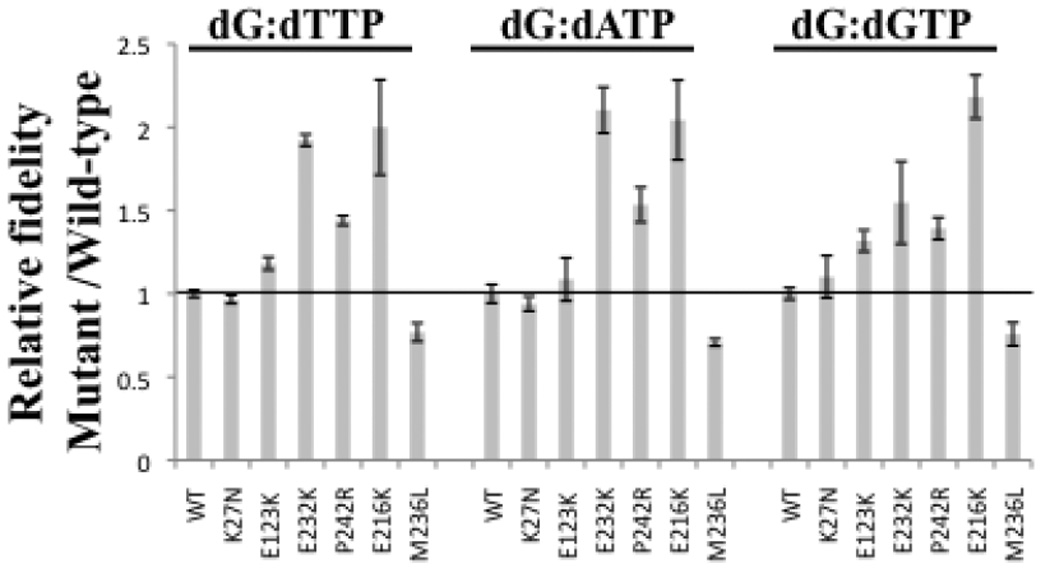

Relative fidelity of variants

We defined fidelity as the ratio of the sum of catalytic efficiency of correct and incorrect nucleotide incorporation over the catalytic efficiency of misincorporation (Table 4). Then, relative fidelities for all variants were obtained by dividing the fidelity of each variant over WT fidelity, using the data from Table 4 (Fig. 3). The fidelity of p.K27N was similar to that of WT enzyme for all misincorporations. The fidelity of p.E123K was similar to that of WT enzyme for dATP misincorporation, but increased for dTTP and dGTP misincorporation (Table 4 and Fig. 3). The DNA synthesis fidelity of variants p.E232K, p.P242R, and p.E216K was increased for all misincorporations compared to WT (Table 4 and Fig. 3). In contrast, the p.M236L variant showed decreased fidelity for all misincorporations (Table 4 and Fig. 3).

TABLE 4.

Incorrect Incorporation Fidelity of a Single dNTP Opposite G in a Gapped Oligo Substrate by Wild-type and Variants

| Mispair |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | G•T | G•A | G•G |

| Fidelitya | |||

| WT | 1.16 (±0.03) ×104 | 1.16 (±0.07) ×104 | 1.48 (±0.05) ×105 |

| p.K27N | 1.12 (±0.03) ×104 | 1.09 (±0.05) ×104 | 1.63 (±0.19) ×105 |

| p.E123K | 1.37 (±0.05) ×104 | 1.26 (±0.15) ×104 | 1.95 (±0.10) ×105 |

| p.E232K | 2.23 (±0.04) ×104 | 2.44 (±0.16) ×104 | 2.29 (±0.43) ×105 |

| p.P242R | 1.67 (±0.03) ×104 | 1.78 (±0.12) ×104 | 2.06 (±0.10) ×105 |

| p.E216K | 2.32 (±0.33) ×104 | 2.37 (±0.28) ×104 | 3.23 (±0.19) ×105 |

| p.M236L | 8.91 (±0.06) ×103 | 8.2 (±0.03) ×103 | 1.12 (±0.10) ×105 |

FIGURE 3.

Relative fidelity of pol β enzyme variants. WT and mutant variants were assayed on a single-nucleotide gapped DNA substrate with a templating dG. Fidelity was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures” and listed on Table 3. These data represent the mean of at least three independent determinations.

Deoxyribose phosphate lyase activity

Unlike the remaining polymerase variants analyzed here, p.K27N is part of the deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) lyase domain of polymerase beta [Dalal et al, 2008]. Thus we compared the dRP lyase activity of p.K27N to wild type, with or without prior addition of apurinic endonuclease I (APE I). The results showed that the p.K27N mutant significantly decreased both the Km and kcat, resulting in a small decrease in catalytic efficiency, Kcat/ Km (Table 5). A similar decrease was observed following APE I treatment (data not shown).

TABLE 5.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for pol β deoxyribose lyase activity

| Enzyme | Kcat (min−1) | Km (nM) | Kcat/Km (nM−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 4.1×10−3 | 262 | 1.6×10−5 |

| p.K27N | 1.1×10−3 | 77 | 1.4×10−5 |

Note: the kinetic values presented are calculated in the absence of APE I, as detailed in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

We have uncovered a significant prevalence of missense nucleotide substitutions of polymerase β in prostate cancer tissue [Makridakis et al., 2009]. In order to assess the potential effect of these seven nucleotide substitutions (Table 1) on polymerase β function, we utilized expression analysis followed by kinetic assays on a DNA substrate containing a single nucleotide gap. Our results demonstrate a significant change in the catalytic activity (measured by the kcat) for both the triple mutant (p.P261L/ p.T292A/ p.I298T) and p.E123K variants (Table 1): the triple mutant has dramatically decreased activity, while the p.E123K shows significantly increased activity. The Km for the correct dNTP substrate (dCTP) was significantly increased (i.e. the affinity was lower) for the triple mutant, p.K27N and p.M236L variants (Table 1). The changes in pol β catalytic properties caused by these mutations resulted in significant reductions in catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km,dCTP) for both the triple mutant and the p.K27N variants (Table 1, Fig. 2). Other somatic variants (such as the p.E123K and p.E232K) showed increased catalytic efficiency compared to WT (Fig. 2), but this trend is within the experimental error of the kinetic assays.

With the exception of the triple mutant (whose expression was about half the WT level) all somatic variants resulted in essentially normal protein steady state levels (data not shown). Thus any change in the observed kinetic values reflects an alteration in the catalytic properties of pol β, and not merely a change in enzyme levels. This is also true for the triple mutant, whose catalytic efficiency is reduced orders of magnitude more than the 2-fold decrease in enzyme levels (Fig. 2). Catalytic efficiencies at steady state levels provide a better measure of the potential effect of the somatic mutations on prostate tumor progression rather than initial velocity or rates (kpol), because they reflect the effect of these mutations over time (i.e. while the mutation is present in the tumor). As previously mentioned, both higher and lower pol β activity or levels result in increased mutagenesis in vivo. Even a 50% reduction in pol β activity or levels results in single-stranded DNA breaks, chromosomal aberrations and mutagenicity [Cabelof et al., 2003]. Based on their significant reduction on pol β catalytic efficiency (Fig. 2), both the triple mutant and the p.K27N variants are expected to result in mutagenicity, and to contribute to prostate cancer progression in vivo. The effect of the somatic mutations that marginally increase pol β activity (such as p.E123K and p.E232K; Fig. 2) is less clear. An intriguing possibility is that some of these mutations affect pol β binding to other components of the BER machinery, such as XRCC1 [Sweasy et al., 2006].

Interestingly, the p.E123K, p.E232K and triple mutant variants are 100% prevalent in their respective prostate tumors (i.e. there is no WT allele in each patient’s tumor; Makridakis et al. [2009]). The dramatic reduction in pol β activity conferred by the triple mutant (Fig. 2), means that the patient carrying this mutation has severely defective short-patch base excision repair in its tumor. This patient is 51 years old and has pT3a stage tumor [Makridakis et al., 2009]. Prostate cancer usually occurs in men older than 60 years [Bruner et al., 1999] suggesting that this pol β variant may contribute to early-onset prostate cancer.

The pol β knockout mouse is neonatal lethal (due to respiratory failure), shows growth retardation, and displays apoptotic cell death in the developing nervous system [Sugo et al., 2000]. The finding of a severely defective pol β variant (the triple mutant) in a prostate cancer patient’s tumor suggests that pol β activity is not essential in the adult prostate. Alternatively, it may be that this patient’s tumor has found alternative ways to compensate for the loss of pol β activity (such as activation of the long-patch base excision repair, which can also repair oxidation damage).

The triple pol β mutant (p.P261L/ p.T292A/ p.I298T) changes residues that are presumed to be important for both function (T292; see Introduction) and structure: P261 forms a structurally important hydrogen bond with glutamine-264 [Pelletier et al., 1996]. P261 lies one residue away from the prostate cancer associated pol β variant p.I260M [Dalal et al., 2005]. Interestingly, the p.I260M mutant is a sequence-specific mutator that is though to exert its effect through the disruption of the hydrogen bond between proline-261 and glutamine-264 [Dalal et al., 2005]. Thus the p.P261L mutation of the triple mutant may also be a mutator mutant. Future biochemical analyses with the three independent mutations that compose the triple mutant may shed some light on the potential functional effects of each of these variants on base excision repair.

Furthermore, the triple pol β mutant affects an enzyme domain that has been previously shown to contain functionally important mutations: The p.E295K pol β mutation, found in gastric cancer, abolishes enzyme activity and induces cellular transformation [Lang et al, 2007]. The p.M282L pol β mutation increased mutagenesis and protein stability [Shah et al, 2001]. The p.K289M mutation, found in colon cancer, also induced mutagenesis [Lang et al, 2004]. These data suggest that the triple pol β mutant may have severe consequences in vivo.

Table 3 demonstrates that most of the somatic pol β mutations assayed here in misincorporation assays significantly change the Km for dNTP compared to WT, but not the kcat. The biggest changes on the kcat for dG: dGTP are afforded by the p.E232K mutant (25% decrease) and the p.M236L mutant (19% increase) (Table 3). kcat for the rest of dNTPs is affected very modestly for all mutants (less than 16%; Table 3). However, the Km for dNTP misincorporation is increased up to 60% for dTTP, 59% for dATP and 72 % for dGTP (all for the p.K27N mutant). Interestingly, most somatic mutations increase the Km for dNTP misincorporation (Table 3). The biggest decrease in the Km for dNTP misincorporation is attained by the p.E232K mutant: a 28% decrease in the Km for dGTP misincorporation.

The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km,dNTP) for dNTP misincorporation is significantly lower than WT for most of the somatic mutations (Table 3). The biggest change on the kcat/Km,dNTP for dTTP misincorporation is achieved by the p.E216K mutant (44% decrease), while for dATP it is a 39% decrease (by p.K27N) and for dGTP it is a 49% decrease (by the p.E216K mutant).

Consistent with the change in catalytic efficiency for misincorporation, most somatic pol β mutations show significantly increased fidelity of DNA synthesis (Fig. 3), suggesting that they function as antimutators. The p.K27N mutation that demonstrated reduced activity for correct incorporation (Fig. 2) displays no change in fidelity compared to WT (Fig. 3). We were unable to measure fidelity for the triple mutant, due to its very low activity for misincorporation (data not shown). The p.E123K mutation displays significantly increased fidelity for dTTP and dGTP (up to 32%), but not dATP (Fig. 3). The p.E232K, p.P242R, and p.E216K mutations display significantly increased fidelity (up to 118%) for all dNTPs (Fig. 3). In contrast, the p.M236L variant showed decreased fidelity compared to WT: 23%, 29%, and 24% for dTTP, dATP, and dGTP, respectively (Table 4 and Fig. 3). Thus, the p.M236L mutation may confer a mutator phenotype. Interestingly, the prostate tumor that bares the p.M236L mutation has microsatellite instability [Makridakis et al., 2009], supporting this hypothesis. Furthermore, the effect of the p.M236L on synthesis fidelity may be due to the destruction (in the mutant) of a hydrogen bond important for template binding (see Introduction).

As mentioned above, the p.E123K and p.E232K variants are 100% prevalent in their respective prostate tumors [Makridakis et al., 2009]. These somatic variants, together with the p.E216K (present in 52% of its respective tumor; Makridakis et al. [2009]), show significantly increased fidelity compared to WT, and thus may function as antimutators. Interestingly, all three of these variants show a trend towards higher pol β activity (although it does not reach statistical significance in our assay; Fig. 2). It is tempting to hypothesize that these three variants may actually reflect the response of prostate tumors to chemotherapy: DNA damage (e.g. alkylation) caused by chemotherapeutic drugs may actually select for tumor mutations that have both increased pol β activity and fidelity, in order to repair the damage. We do not have data on the chemotherapeutic regimen given to these patients, so we cannot directly probe this scenario at this time. However, increased pol β expression has been significantly associated with poorer chemotherapeutic response and prognosis in colorectal cancer [Iwatsuki et al., 2009]. An alternative model is that the p.E123K, p.E232K and p.E216K pol β mutations are actually “passengers”, i.e. not “drivers” of tumor progression.

Several previously characterized pol β mutants exhibit misincorporation bias. For example, the p.D246V pol β mutant, present in the “flexible loop” (where the p.P242R mutant also lies; see Introduction), preferentially misincorporates dTTP opposite to templated dG [Dalal et al., 2004]. This misincorporation bias makes the p.D246V a mutator mutant mainly for C>T transitions. We examined our somatic pol β mutants for misincorporation bias. Table 4 indicates a similar trend for mutator/ antimutator status for all template: dNTP misincorporations and all somatic mutations that affect fidelity of DNA replication (including the p.P242R). Thus, we conclude that these somatic mutations do not result in significant misincorporation bias. However, pol β misincorporation bias is also known to depend on sequence context. Thus it is possible that varying the template sequence may result in distinct misincorporation bias for specific mutants. Future experiments will test this hypothesis following expression analysis of the somatic pol β mutants in vivo.

The triple pol β mutant dramatically affects the Km for dCTP (15-fold increase). None of the residues that bind dCTP (based on the crystal structure; [Sawaya et al. 1997]) is directly mutated in the triple mutant. However, D276 of pol β, binds dCTP [Sawaya et al., 1997], and is also part of an α-helix that is in close proximity with two stacked β -sheets that include two of the residues mutated in the triple mutant, p.T292 and p.I298 (Jmol; http://molvis.sdsc.edu/fgij/fg.htm?mol=2FMS). Mutations of these residues from threonine to alanine (at position 292) and from isoleucine to threonine (at position 298) may destabilize the local structure, perhaps reducing the stacking effect (especially the I298T mutation) and thus the interaction between the β -sheets and the α-helix containing p.D276. This in turn could affect the triple mutant enzyme’s affinity for dCTP.

The p.K27N pol β mutant significantly decreases catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km,dCTP) without changing kcat (Table 1). The p.K27N effect on the pol β catalytic efficiency can be explained by a 72% increase in the Km for dCTP (Table 1). The p.K27N mutation is not physically close to any of the residues that bind dCTP ([Sawaya et al. 1997]; Jmol; http://molvis.sdsc.edu/fgij/fg.htm?mol=2FMS). However, the Km for dCTP can increase due to: (a) an increase in the dissociation constant Kd (for dCTP), (b) slower rate of dCTP insertion, or (c) decreased binding affinity for the DNA template. K27 of pol β is only 6 Angstroms away from the DNA template (Jmol; http://molvis.sdsc.edu/fgij/fg.htm?mol=2FMS). The p.K27N mutation abolishes a positive charge on lycine 27, which may destabilize the interaction between this residue and the negatively charged DNA template backbone, resulting in lower affinity.

A similar scenario may explain the effect of the triple mutant on the Km for dCTP (alternatively explained above). The p.T292A mutation present in the triple pol β mutant is expected to abolish a hydrogen bond between this pol β residue and the DNA template (see Introduction), which may result in decreased affinity for the DNA template. This, in turn, could result in increased Km for dCTP (as mentioned above for the K27N mutant).

Unlike the dramatic decrease on dRP lyase activity caused by the previously characterized p.L22P pol β mutant [Dalal et al, 2008], the p.K27N variant characterized here shows a small decrease in catalytic effiency (Table 5). This finding may be due to the positioning of the side chain of K27, which points away from the lyase active site [Prasad et al, 2005].

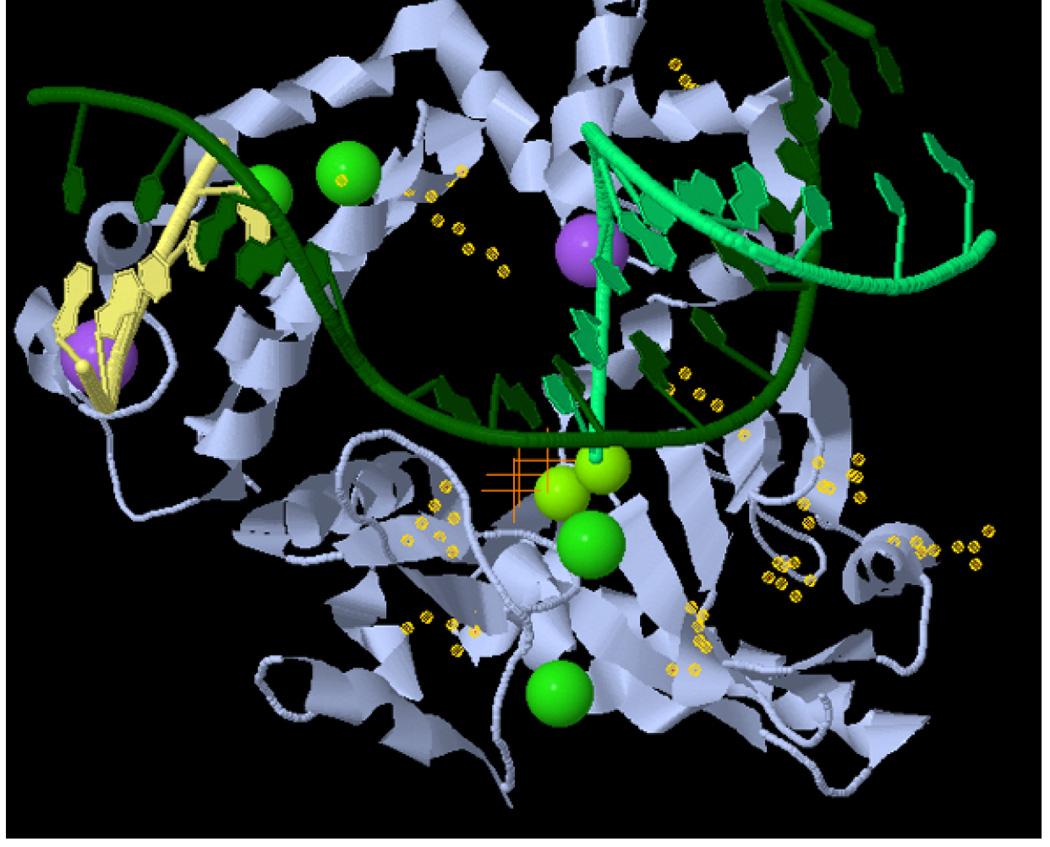

The crystal structure of human polymerase β is available [Pelletier et al., 1996]. Visualization of the somatic mutations that we characterized here in pol β structure (Fig. 4) indicates that these variants are not in a specific part of the protein, but they are distributed throughout the structure. Some of the mutant residues are in areas of protein-DNA interaction, others in areas of interaction between protein domains (e.g. between two β-sheets) while others are in areas critical for structural maintenance [Pelletier et al., 1996]. These observations suggest that multiple structural parts of polymerase β are critical for BER function. The observation of several pol β mutants that affect DNA synthesis fidelity without been part of the active site is of particular interest.

FIGURE 4.

Location of the somatic pol β mutations. The structure of human DNA polymerase beta with dUTP (orange crosses) opposite dA and a gapped DNA substrate (2FMS) is shown using Jmol (http://molvis.sdsc.edu/fgij/fg.htm?mol=2FMS). Yellow “halos” indicate the side groups of the mutated residues. The gapped DNA substrate is shown in green and yellow, the polymerase β in gray. Small green spheres indicate Mg2+ ions, large green ones Cl− ions, and purple ones Na+ ions.

In summary, we biochemically analyzed all missense somatic mutations of polymerase β that we previously identified in prostate cancer [Makridakis et al., 2009]. We report that all missense somatic pol β mutations have functionally significant effects: the triple mutant and the p.K27N variants affect catalytic efficiency, while the p.M236L, p.E123K, p.E232K, p.P242R, and p.E216K mutations alter the fidelity of DNA synthesis. These somatic mutations are present in a total of 7 out of 26 (27%) prostate cancer patients [Makridakis et al., 2009]. If one adds to this total the two patients with splice junction mutations (that are predicted to result in amino acid deletions; Makridakis et al. [2009]), then we conclude that 9/26 (35%) of prostate cancer patients have functional somatic mutations of pol β. Functional pol β mutations have been identified at a high frequency in other types of cancer [Starcevic et al., 2004]. Thus interfering with polymerase β activity may be a common mechanism of carcinogenesis. Moreover, our data significantly expands the current knowledge on the molecular determinants of both activity and fidelity for a model monomeric eukaryotic polymerase, pol β.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Juergen Reichardt (Sydney) and Wanguo Liu (New Orleans) for critically reading this manuscript. NMM is funded by the grant # P20RR020152-06, from the NIH.

REFERENCES

- An CL, Lim WJ, Hong SY, Kim EJ, Shin EC, Kim MK, Lee JR, Park SR, Woo JG, Lim YP, Yun HD. Analysis of bgl Operon Structure and Characterization of β-Glucosidase from Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum LY34. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2004;68:2270–2278. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard WA, Shock DD, Yang XP, DeLauder SF, Wilson SH. Loss of DNA polymerase beta stacking interactions with templating purines, but not pyrimidines, alters catalytic efficiency and fidelity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8235–8242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structural insights into DNA polymerase beta fidelity: hold tight if you want it right. Chem Biol. 1998;5:R7–R13. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergoglio V, Pillaire MJ, Lacroix-Triki M, Raynaud-Messina B, Canitrot Y, Bieth A, Garès M, Wright M, Delsol G, Loeb LA, Cazaux C, Hoffmann JS. Deregulated DNA polymerase β induces chromosome instability and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3511–3514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose-Basu B, DeRose EF, Kirby TW, Mueller GA, Beard WA, Wilson SH, London RE. Dynamic Characterization of a DNA Repair Enzyme: NMR Studies of [methyl-13C]Methionine-Labeled DNA Polymerase β. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8911–8922. doi: 10.1021/bi049641n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner DW, Baffoe-Bonnie A, Miller S, Diefenbach M, Tricoli JV, Daly M, Pinover W, Grumet SC, Stofey J, Ross E, Raysor S, Balshem A, Malick J, Engstrom P, Hanks GE, Mirchandani I. Prostate cancer risk assessment program. A model for the early detection of prostate cancer. Oncology (Huntingt) 1999;13:325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabelof DC, Guo Z, Raffoul JJ, Sobol RW, Wilson SH, Richardson A, Heydari AR. Base excision repair deficiency caused by polymerase β haploinsufficiency: accelerated DNA damage and increased mutational response to carcinogens. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5799–5807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagovetz AM, Sweasy JB, Preston BD. Increased activity and fidelity of DNA polymerase β on single-nucleotide gapped DNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27501–27504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal S, Chikova A, Jaeger J, Sweasy JB. The Leu22Pro tumor-associated variant of DNA polymerase beta is dRP lyase deficient. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:411–422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal S, Kosa JL, Sweasy JB. The D246V mutant of DNA polymerase beta misincorporates nucleotides: evidence for a role for the flexible loop in DNA positioning within the active site. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:577–584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal S, Hile S, Eckert KA, Sun KW, Starcevic D, Sweasy JB. Prostate-cancer-associated I260M variant of DNA polymerase β is a sequence-specific mutator. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15664–15673. doi: 10.1021/bi051179z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi Y, Shuin T, Tsuruga H, Uemura H, Torigoe S, Kubota Y. DNA polymerase β gene mutation in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2827–2829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg EC. DNA damage and repair. Nature. 2003;421:436–440. doi: 10.1038/nature01408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MF. Error-prone repair DNA polymerases in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:17–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.083101.124707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid S, Eckert KA. Chemotherapeutic nucleoside analogues and DNA polymerase β. Proc Amer Assoc Cancer Res. 2005;46:319–320. [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki M, Mimori K, Yokobori T, Tanaka F, Tahara K, Inoue H, Baba H, Mori M. A platinum agent resistance gene, POLB, is a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:261–266. doi: 10.1002/jso.21275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidane D, Jonason AS, Gorton TS, Mihaylov I, Pan J, Keeney S, de Rooij DG, Ashley T, Keh A, Liu Y, Banerjee U, Zelterman D, Sweasy JB. DNA polymerase beta is critical for mouse meiotic synapsis. EMBO J. 2010;29:410–423. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosa JL, Sweasy JB. 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine-resistant Mutants of DNA Polymerase β Identified by in Vivo Selection. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3851–3858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T, Dalal S, Chikova A, DiMaio D, Sweasy JB. The E295K DNA polymerase beta gastric cancer-associated variant interferes with base excision repair and induces cellular transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5587–5596. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01883-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T, Maitra M, Starcevic D, Li SX, Sweasy JB. A DNA polymerase beta mutant from colon cancer cells induces mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6074–6079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308571101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SX, Vaccaro J, Sweasy JB. Involvement of phenylalanine 272 of DNA polymerase β in discriminating between correct and incorrect deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4800–4808. doi: 10.1021/bi9827058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitra M, Gudzelak A, Jr, Li SX, Matsumoto Y, Eckert KA, Jager J, Sweasy JB. Threonine 79 is a hinge residue that governs the fidelity of DNA polymerase β by helping to position the DNA within the active site. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35550–35560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204953200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makridakis NM, Caldas Ferraz LF, Reichardt JKV. Genomic analysis of cancer tissue reveals that somatic mutations commonly occur in a specific motif. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:39–48. doi: 10.1002/humu.20810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matakidou A, el Galta R, Webb EL, Rudd MF, Bridle H, Eisen T, Houlston RS GELCAPS Consortium. Genetic variation in the DNA repair genes is predictive of outcome in lung cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2333–2340. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno V, Gemignani F, Landi S, Gioia-Patricola L, Chabrier A, Blanco I, González S, Guino E, Capellà G, Canzian F. Polymorphisms in genes of nucleotide and base excision repair: risk and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2101–2108. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce CL, Van Den Berg DJ, Makridakis N, Reichardt JK, Ross RK, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE. No association between the SRD5A2 gene A49T missense variant and prostate cancer risk: lessons learned. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2456–2461. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier H, Sawaya MR, Wolfle W, Wilson SH, Kraut J. Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase beta complexed with DNA: implications for catalytic mechanism, processivity, and fidelity. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12742–12761. doi: 10.1021/bi952955d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad R, Batra VK, Yang XP, Krahn JM, Pedersen LC, Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structural insight into the DNA polymerase beta deoxyribose phosphate lyase mechanism. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:1347–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad R, Beard WA, Strauss PR, Wilson SH. Human DNA polymerase beta deoxyribose phosphate lyase. Substrate specificity and catalytic mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15263–15270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JD, Kunkel TA. The Fidelity of Eukaryotic DNA Replication. In: DePamphilis ML, editor. DNA Replication in Eukaryotic Cells: Concepts, Enzymes and Systems. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor; 1996. pp. 217–247. [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya MR, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Kraut J, Pelletier H. Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase beta complexed with gapped and nicked DNA: evidence for an induced fit mechanism. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11205–11215. doi: 10.1021/bi9703812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon KJ, Kashani-Sabet M, Miyachi H. Differential gene expression in human cancer cells resistant to cisplatin. Cancer Invest. 1989;7:581–587. doi: 10.3109/07357908909017533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servant L, Cazaux C, Bieth A, Iwai S, Hanaoka F, Hoffmann JS. A role for DNA polymerase β in mutagenic UV lesion bypass. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50046–50053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AM, Conn DA, Li SX, Capaldi A, Jäger J, Sweasy JB. A DNA polymerase β mutator mutant with reduced nucleotide discrimination and increased protein stability. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11372–11381. doi: 10.1021/bi010755y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starcevic D, Dalal S, Sweasy JB. Is there a link between DNA polymerase beta and cancer? Cell Cycle. 2004;3:998–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugo N, Aratani Y, Nagashima Y, Kubota Y, Koyama H. Neonatal lethality with abnormal neurogenesis in mice deficient in DNA polymerase β. EMBO J. 2000;19:1397–1404. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweasy JB, Lang T, DiMaio D. Is base excision repair a tumor suppressor mechanism? Cell Cycle. 2006;5:250–259. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.3.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visakorpi T, Hyytinen E, Koivisto P, Tanner M, Keinänen R, Palmberg C, Palotie A, Tammela T, Isola J, Kallioniemi OP. In vivo amplification of the androgen receptor gene and progression of human prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 1995;9:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TE, Lieber MR. Efficient processing of DNA ends during yeast nonhomologous end joining. Evidence for a DNA polymerase β (Pol4)-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23599–23609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.