Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and methamphetamine (METH) dependence are independently associated with neuronal dysfunction. The coupling between cerebral blood flow (CBF) and neuronal activity is the basis of many task-based functional neuroimaging techniques. We examined the interaction between HIV infection and a previous history of METH dependence on CBF within the lenticular nuclei (LN). Twenty-four HIV−/METH−, eight HIV−/METH+, 24 HIV+/METH−, and 15 HIV+/METH+ participants performed a finger tapping paradigm. A multiple regression analysis of covariance assessed associations and two-way interactions between CBF and HIV serostatus and/or previous history of METH dependence. HIV+ individuals had a trend towards a lower baseline CBF (−10%, p=0.07) and greater CBF changes for the functional task (+32%, p=0.01) than HIV− subjects. Individuals with a previous history of METH dependence had a lower baseline CBF (–16%, p= 0.007) and greater CBF changes for a functional task (+33%, p=0.02). However, no interaction existed between HIV serostatus and previous history of METH dependence for either baseline CBF (p=0.53) or CBF changes for a functional task (p=0.10). In addition, CBF and volume in the LN were not correlated. A possible additive relationship could exist between HIV infection and a history of METH dependence on CBF with a previous history of METH dependence having a larger contribution. Abnormalities in CBF could serve as a surrogate measure for assessing the chronic effects of HIV and previous METH dependence on brain function.

Keywords: Human immunodeficiency virus, Methamphetamine, Cerebral blood flow, Lenticular nuclei, Highly active antiretroviral therapy

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) quickly crosses the blood–brain barrier probably through a “Trojan horse” mechanism. Once inside the brain, HIV can trigger the release of a cascade of cytokines and chemokines that impair neuronal, astrocytic, and microglia function (Ances and Ellis 2007). Changes in these mediators can alter brain function in HIV+ individuals causing diminished performance of activities of daily living, poor adherence to medication, and an increased proclivity to engage in dangerous behaviors (Ellis et al. 2002).

Substance dependence is a common risk factor for HIV transmission. Methamphetamine (METH), a psychostimulant, has emerged as a major drug of abuse (Cherner et al. 2010). A double epidemic has arisen as METH injection users have a greater risk of acquiring HIV (Flora et al. 2003; Scott et al. 2007). Both HIV and METH dependence could affect dopamine and glutamatergic transmission and lead to neuronal injury and death (Langford et al. 2004; Marshall et al. 1993; Stephans and Yamamoto 1994; Wang et al. 2004). Each can independently produce neuropsychometric deficits in attention/working memory, abstraction, episodic memory, and motor speed (Chana et al. 2006; Cherner et al. 2005; Scott et al. 2007). However, only a few studies have investigated the possible interaction between HIV and a previous history of METH dependence (Chang et al. 2005; Jernigan et al. 2005; Taylor et al. 2007) especially within subcortical areas such as the lenticular nuclei (LN; putamen and globus pallidus).

Neuroimaging can provide a non-invasive technique to assess the impact of HIV and previous history of METH dependence on brain function. Differences in brain activation due to HIV serostatus have been mapped using blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; Ances et al. 2008b; Chang et al. 2001; Juengst et al. 2007). HIV+ individuals often recruit additional brain structures to meet functional demand (Chang et al. 2001, 2004). However, the assumption that BOLD activity is a quantitative measure of underlying neural activity remains problematic (Buxton 2010). In particular, the BOLD response reflects a cascade of physiological events and mediators that couple neural activity with changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume, and cerebral metabolism. An accurate interpretation of possible observed differences in the magnitude of BOLD responses between HIV+ and HIV− subjects requires additional knowledge concerning both baseline and functional changes in CBF for a task. Resting CBF has been previously shown to be reduced by HIV infection (Ances et al. 2006, 2009) and chronic METH dependence (Chang et al. 2002).

With the increasing application of neuroimaging to understand the pathopysiological changes associated with various disease states, a growing need therefore exists for assessing possible interactions between HIV and co-variables such as METH. The current study assesses the separate and joint impact of HIV and previous history of METH dependence on CBF within the LN which is a dopaminergicrich area that is often injured by each of these disorders.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 71 participants (21–65 years old) were recruited for this study conducted at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. The Human Research Protections Program at UCSD approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained after each subject was presented a complete description of the study. Participants were recruited from community-based outreach programs at treatment facilities that focus on HIV infection and METH dependence.

Portions of the substance use disorders section of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID; Spitzer et al. 1992) were administered in order to assess each participant's current and lifetime history of dependence on certain classes of substances of abuse (i.e., alcohol, marijuana, METH, cocaine, and hallucinogens). Participants were included within the METH dependence groups if they met the DSM-IV criteria for METH dependence at some point of their life (substance use at least ten occasions in any 1-month period; Robins et al. 1988). All subjects with a previous history of METH dependence subjects were required to have a minimum of 2 months of self-reported abstinence prior to imaging (Simon et al. 2010).

Individuals with METH dependence often have a history of utilizing other substances of abuse (Cherner et al. 2010). Potential participants were excluded if they met the DSM-IV criteria for dependence on other substances of abuse (except marijuana and alcohol) unless such dependence was episodic in nature and occurred more than 1 year prior to scanning. The METH− groups consisted of participants who did not meet criteria for METH use disorders and were not habitual users. To ensure no recent use of any substances of abuse, we performed a urine toxicology screen (METH, cocaine, opiates, phenylcyclidine, and cannabis) prior to imaging with only subjects with a confirmed negative test imaged. Heavy substance use was defined by answering affirmative to at least three questions on the SCID for that particular substance (Spitzer et al. 1992).

Participants with a history of head injury with loss of consciousness greater than 30 min, penetrating skull wound, head injury, or a history of neurological or psychiatric illness that could possibly affect finger tapping task performance (e.g., active seizure disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar affective disorder with psychotic features) were also excluded. All HIV+ participants had no history of central nervous system opportunistic infection based on self-report, which was further confirmed after reviewing structural MRI scans (B.A).

Based upon these criteria, participants were stratified according to HIV serostatus (HIV+ or HIV−) and previous history of METH dependence (METH+ or METH−). All HIV+ subjects were either naïve to highly active antiretrovirals (HAART) or were on a stable regimen for at least 3 months prior to imaging. Blood HIV RNA viral load (VL), hematocrit, and CD4+ cell counts were obtained for HIV+ participants within 4 months of scanning. An ultrasensitive assay of plasma VL was determined by a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (Amplicor®, Roche Diagnostic Systems, Indianapolis, IN, USA; lower quantification limits, <50 copies/mL). CD4+ cell count nadir was obtained by self-report or by direct measurement if the CD4+ cell count was lower than self-reported value.

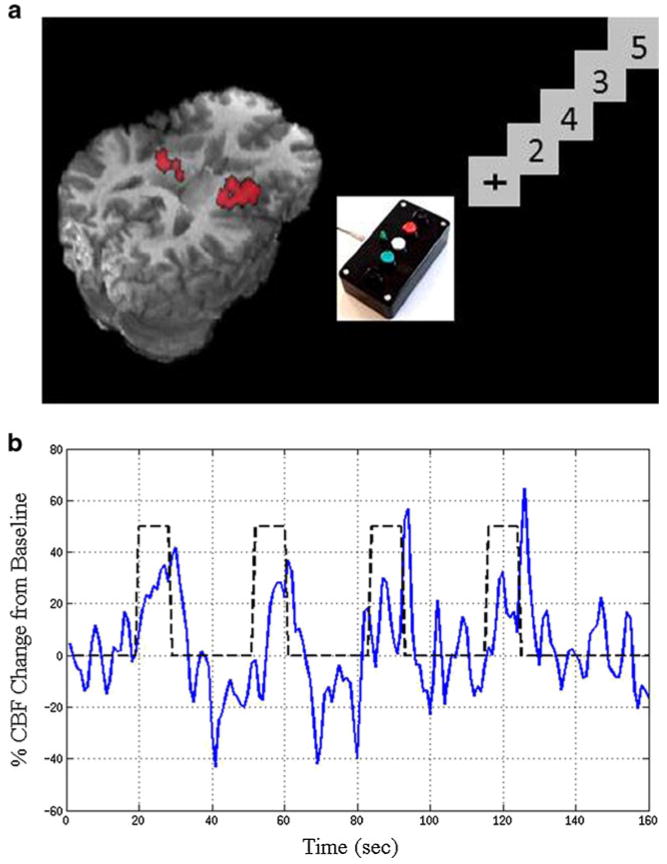

fMRI parameters

Imaging was performed on a three Tesla whole body system (3T General Electric Excite, Milwaukee, WI, USA) using an eight-channel receive head coil. High-resolution structural images for anatomical evaluation were acquired as previously described (Ances et al. 2006, 2009, 2010). The LN were chosen as they receive widespread input from cortical areas with their output directed towards the frontal lobes. Changes in CBF within the LN were determined for a complex finger tapping (2 Hz) functional activation task (Vafaee and Gjedde 2004). Numbers in the center of the screen cued right hand finger pressing on appropriate keys of a four-button response box with a fixed motor sequence (2–4–3–5) used for all subjects (Fig. 1a). Subject performance was observed to ensure compliance (Ances et al. 2010). The stimulus frequencies were chosen to maximize activation within the LN (Allison et al. 2000; Kastrup et al. 2002). A block design was used consisting of four activation periods (20 s in length) alternating with four rest portions (60 s in length). Each of the rest periods consisted on an isoluminant gray screen with a center fixation square. A single run consisted of 60 s of rest, followed by four cycles of task/rest, followed by an additional 30 s of rest. Each run was therefore 410 s in duration.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of magnetic resonance imaging scan and functional task paradigm performed by each subject. Activated voxels within the lenticular nuclei (LN) are highlighted in red. b Cerebral blood flow (CBF) time course for functional task

Based on previous imaging parameters (Ances et al. 2010; Perthen et al. 2008a, b; Restom et al. 2008), CBF measurements were obtained by arterial spin labeling (ASL). Four axial slices, that included the LN, were acquired in a linear fashion from bottom to top. During all scans, subjects had constant physiological monitoring including pulse oximetry and respiratory excursions.

Data analysis of fMRI

Analysis was performed as previously described (Ances et al. 2008a). Briefly, images were co-registered with corrections performed for possible subject movement (Chiarelli et al. 2007; Perthen et al. 2008a). The LN were manually traced in an axial view and edited in sagittal and coronal views. Anatomical images were resampled to match functional images. A general linear model (GLM) was used to identify changes in CBF within clusters of voxels within the LN mask using an overall significance threshold of p=0.05 applied to the first echo data (Mumford et al. 2006; Restom et al. 2008). A stimulus-related regressor was obtained by convolving a box car response with a gamma density function (Boynton et al. 1996). Cardiac and respiratory fluctuations were included as both constant and linear terms and used as nuisance regressors. Pre-whitening was performed using an autoregressive model (Burock and Dale 2000). Correction for multiple comparisons was performed using AlphaSim (Cox 1996).

A CBF time series was first computed by taking a running subtraction of the control and tag image series. Each data point was calculated from the difference between that value and the average of the two nearest neighbors in time with adjustments made in the sign so that each point represents a subtraction of tag from control images. Mean changes in CBF for the functional stimulus were averaged from voxel time courses within the LN after removal of the physiological noise components estimated from the GLM. For the functional task, all runs were concatenated with both linear and quadratic drifts removed (Restom et al. 2008). Fractional changes in CBF for the functional stimulus were calculated as the average over a 15-s period starting at the midpoint of each stimulus presentation, approximating the plateau portion of the response (Fig. 1b; Ances et al. 2010; Perthen et al. 2008a, b).

To determine the change in CBF (ΔCBF) for the functional task, fractional changes in CBF for the functional task were multiplied by the corresponding mean baseline perfusion in the same voxel. Total absolute functional changes in CBF with activation were determined by adding ΔCBF to the baseline CBF. The LN volume of each participant was obtained from the number of voxels within manually traced regions and expressed in cubic millimeters (e.g., 1 voxel=1 mm3; Ances et al. 2006; Cohen et al. 2010).

Due to inhomogeneities in the coil sensitivity profile, the CBF time series from the baseline scan were corrected from the smoothed minimum contrast images (Wang et al. 2005). CBF values were converted to physiological units (mL/100 gm/min) using the CSF image as a reference signal to determine the fully relaxed magnetization of blood (Chalela et al. 2000). The mean baseline CBF was averaged over all time points within activated LN voxels.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared amongst the four groups using Chi-square tests (for dichotomous variables) and analysis of variance (ANOVA) F tests (for continuous variables). A multiple regression analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) assessed the association of HIV serostatus and previous history of METH dependence on CBF values (baseline CBF, fractional changes in CBF for the functional task, and total functional changes in CBF for the task). CBF values were log10-transformed to improve normality and back-transformed to the natural scale for plotting and reporting. The ANCOVA model initially included HIV, previous history of METH dependence, and their two-way interaction. If the two-way interaction between HIV and previous history of METH dependence was not statistically significant (i.e., Wald test, p>0.05), the interaction term was removed, and only the main effects of HIV and METH were considered. In order to control for possible effects of age on CBF, a continuous term for age was added to the model, if statistically significant (Wald test, p<0.05). For the final model, effect sizes for HIV infection and previous history of METH dependence (and 95% confidence intervals) were computed as differences between groups as multiples of the standard deviation of the outcome.

Results

Demographic variables of participants

All subjects tolerated the scanning session with no differences seen in movement during scanning for any of the groups. No significant distinctions in age and sex were observed amongst the four groups (Table 1). Many of the HIV+ participants were on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART; 62%) with the HIV+ group overall having a median CD4+ cell count of 525 cells/μL and median CD4+ cell count nadir of 302 cells/μL. HIV+ participants had been infected for on average for 6 years.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical variables for participants.

| HIV−/METH− (n=24) | HIV−/METH+ (n=8) | HIV+/METH− (n=24) | HIV+/METH+ (n=15) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 41±14 | 43±8 | 39±13 | 43±11 | 0.43 |

| Sex (% female) | 33 | 38 | 8 | 13 | 0.09 |

| Education | 13±2 | 12±1 | 13±1 | 12±1 | 0.76 |

| % Non-white | 12.5 | 37.5 | 41.6 | 26.7 | 0.15 |

| Substance use characteristics | |||||

| Median duration of METH use (years) | NA | 10±3 | NA | 11±4 | 0.56 |

| Frequency of METH use (days/week) | NA | 5±4 | NA | 6±4 | 0.28 |

| Length of abstinence from METH use (months) | NA | 6±3 | NA | 5±3 | 0.87 |

| % with history of heavy marijuana use during lifetime | 17% | 75% | 54% | 87% | 0.0003 |

| % with history of heavy alcohol use during lifetime | 25% | 63% | 46% | 73% | 0.0006 |

| HIV characteristics | |||||

| Median CD4+ cell count (cells/μL; IQRs) | NA | NA | 565 (341, 785) | 460 (192, 548) | 0.43 |

| Median nadir CD4+ cell count (cells/μL; IQRs) | NA | NA | 331 (168, 507) | 258 (50, 339) | 0.62 |

| % Virologically suppressed (<50 copies/mL) | NA | NA | 67% | 54% | 0.42 |

| Median plasma viral load (log10; SD) | NA | NA | 2.31 ±0.60 | 2.44±0.50 | 0.22 |

| Duration of infection (in years; SD) | NA | NA | 7±1 | 5±2 | 0.47 |

| % taking antiretrovirals at time of scan | NA | NA | 81% | 78% | 0.79 |

Subjects with a previous history of METH dependence (both HIV+ and HIV−) had been using this drug frequently in the past. METH was the preferred drug of choice by these participants. The four participant groups were compared on differences between rates of past alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and hallucinogen use according the SCID (Spitzer et al. 1992). METH+ subjects had a greater lifetime history of alcohol (p< 0.006) and marijuana (p<0.003) dependence, but not cocaine or hallucinogens.

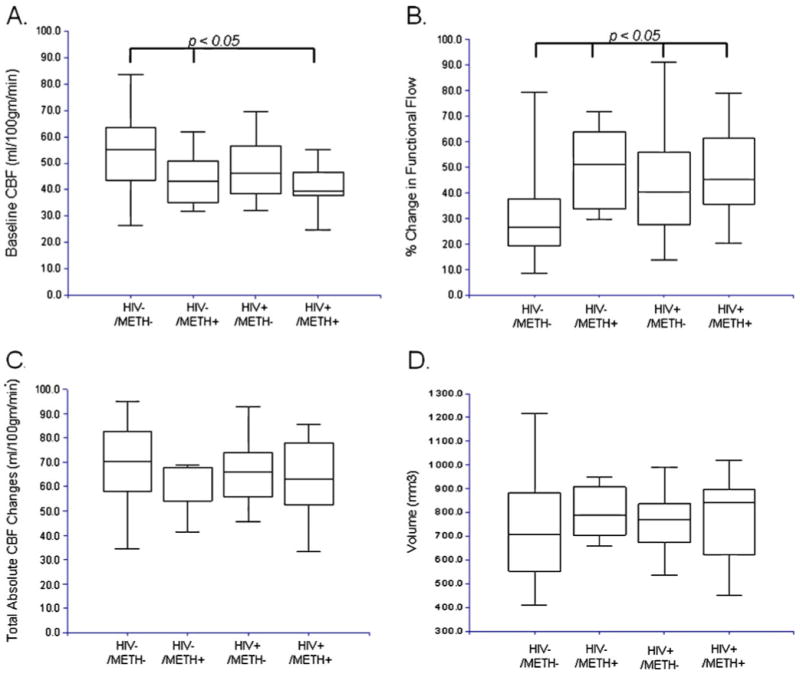

Effects of HIV and METH dependence on baseline CBF

Baseline CBF was significantly greater for the HIV−/METH− group compared to all other groups (p=0.006; Fig. 2a). HIV infection (independent of METH dependence) was associated with a mild reduction in baseline CBF, but did not reach statistical significance (−10%, p= 0.07). No correlations existed between baseline CBF and current blood CD4+ cell count (r2=0.058) or current plasma viral load (VL; r2=0.002) for all of the HIV+ participants (both HIV+/METH and HIV+/METH−). Similar results were seen for CD4+ cell count nadir (data not shown). A previous history of METH dependence (independent of HIV serostatus) was associated with a lower baseline CBF (−16%, p=0.007). Duration of METH dependence did not correlate with baseline CBF (r2=0.022).

Fig. 2.

Changes in CBF and volume for HIV−/METH−, HIV−/METH+, HIV+/METH− and HIV+/METH+ groups. a Baseline CBF was significantly higher for HIV−/METH− subjects compared to all other groups. b HIV−/METH− subjects had a significantly lower magnitude in the CBF changes for a functional task compared to all other groups. c Absolute total CBF changes were similar for all groups with reductions in baseline CBF cancelling out increases in changes in CBF for a functional task. d Absolute LN volumes were similar for all groups. For all boxplots, the top and bottom of the box are the 25th and 75th percentiles. The length of the box is the interquartile range (IQR). The line through the middle of the box is the median (the 50th percentile). The T-shaped lines that extend from each end of the box represent the minimum and maximum of all the data

Effects of HIV and METH dependence on CBF changes for a functional task

Reproducible CBF time series data were obtained for each subject. The time series for measured CBF changes was averaged across cycles to determine the average fractional changes in CBF for the functional stimulus. HIV−/METH− subjects had significantly smaller fractional changes in CBF for the functional task compared to other groups (p=0.002; Fig. 2b). Both HIV positive status (+32%, p=0.01) and a previous history of METH dependence (+33%, p=0.02) were associated with larger fractional changes in CBF for the functional task (Table 2). No correlation existed between changes in CBF for the functional task and current blood CD4+ cell count (r2=0.003) or plasma VL (r2= 0.005) for HIV+ subjects. Similar results were seen for nadir CD4+ cell count (data not shown). Duration of METH dependence was not correlated with changes in CBF for the functional task (r2=0.004). Overall, no significant differences in absolute functional changes in CBF for the task (p=0.38) were seen across groups (Fig. 2c).

Table 2. Effect of METH dependence and HIV status on neuroimaging outcomes.

| Effect of factors on outcome (95% CI) | Effect size (95% CI) | p value | R-squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline CBF | 11.1% | |||

| METH+ effect | −15.7% (−25.2%, −5.0%) | −0.72 (−1.22, −0.21) | 0.007** | |

| HIV+ effect | −10.0% (−19.6%, 0.7%) | −0.44 (−0.91, 0.03) | 0.070 | |

| METH+ × HIV+ interaction | 0.531 | |||

| Functional changes in CBF | 23.1% | |||

| METH+ effect | 32.9% (5.4%, 67.5%) | 0.63 (0.12, 1.14) | 0.018* | |

| HIV+ effect | 31.8% (6.3%, 63.5%) | 0.61 (0.13, 1.08) | 0.014* | |

| Age (per 15 years) | 17.4% (1.5%, 35.9%) | 0.35 (0.03, 0.68) | 0.035* | |

| METH+ × HIV+ interaction | 0.103 | |||

| Absolute changes in CBF | 3.8% | |||

| METH+ effect | −8.1% (−18.6%, 3.8%) | −0.34 (−0.85, 0.15) | 0.181 | |

| HIV+ effect | −4.2% (−14.6%, 7.4%) | −0.18 (−0.65, 0.29) | 0.462 | |

| METH+ × HIV+ interaction | 0.985 | |||

| Absolute volume of LN | 1.3% | |||

| METH+ effect | 8.9 (−10.4, 28.3) | 0.374 | ||

| HIV+ effect | 2.0 (−16.2, 20.2) | 0.832 | ||

| METH+ × HIV+ interaction | 0.766 |

The absence of a significant interaction between METH and HIV indicates that METH and HIV had additive effects on the outcome. METH and HIV were adjusted for each other, and for age, when an age effect was present. For each outcome and factor, a group difference (and 95% CI), Cohen's effect size d (and 95% CI), p value, and proportion of variability explained by R-squared were computed. The p values are from the partial F test of regression

Effects of HIV and METH dependence on absolute LN volume

We also examined if observed differences in CBF could be attributed to changes in LN volume. No significant differences were seen amongst groups (p=0.20; Fig. 2d). Both HIV positive status (+2%, p=0.83) and previous history of METH dependence (+8.9%, p=0.37) were not associated with significant changes in LN volume (Table 2).

Interaction between HIV and METH dependence for each fMRI measure

We also investigated if an interaction (either additive or synergistic) was present between HIV status and a previous history of METH dependence. In our model, the effect of the factor is the difference between groups, e.g., between METH+ and METH−, after controlling for HIV status, and age when appropriate. An observed negative difference in the absolute changes in CBF due to METH+ indicates that the means in the METH+ group were lower than in the METH− group, within each HIV status. A similar result was also seen for HIV for absolute changes in CBF (Table 2). The lack of a significant interaction between HIV and METH for each of the neuroimaging variables suggests that the effects of METH and HIV on the outcome are additive for CBF. Similar results were seen for changes in CBF for the functional task (p=0.10) and absolute LN volume (p=0.76; Table 2). For each fMRI parameter, a larger contributory effect was due to a previous history of METH dependence compared to HIV serostatus.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that both HIV infection and previous METH dependence affect CBF. HIV+/METH+ participants had significantly lower baseline CBF and higher fractional changes in CBF for the functional task compared to HIV−/METH− subjects. It is interesting, though, that there was no significant group difference in absolute functional CBF changes for the task, suggesting that reduced fractional changes in CBF could be largely due to a reduced baseline CBF value. These observations in the absence of absolute volumetric changes (Ances et al. 2006) could suggest neuronal dysfunction in the LN, which is an area containing dopaminergic nerve terminals.

The lack of absolute LN volumetric changes for HIV+/METH+ participants is in good agreement with a previous morphometric study (Jernigan et al. 2005). While HIV can lead to volume reduction (Ances et al. 2006; Cohen et al. 2010), METH dependence has been shown to cause an expansion in the same areas such that they may cancel each other. HIV+/METH+ participants may therefore have similar values to HIV−/METH− subjects. The exact etiology as to how METH causes an increase in volume remains poorly understood, but a previous study using an animal model suggests aberrant dendritic sprouting (Takaki et al. 2001). We observed a small but non-significant increase in the absolute LN volume for HIV+/METH+ subjects. The broader variability seen in HIV−/METH− subjects may reflect differences in gender proportion amongst groups with males typically having larger head sizes than females.

HIV−/METH+ individuals had lower baseline CBF and greater fractional changes in CBF for the functional task compared to HIV−/METH− subjects. Observed values for baseline CBF within HIV−/METH− subjects were similar to those seen within a comparable group using a gold standard for measurement of CBF-single photon emission tomography (SPECT; Osawa et al. 2004). Acute METH exposure can increase dopamine release and impair vascular compliance leading to hemorrhages and strokes (Westover et al. 2007). However, chronic METH dependence can also deplete dopamine pools (Bamford et al. 2008) at the synapse. This could lead to a decrease in dopamine transmission levels at rest causing a subsequent reduction in both metabolic demands and baseline CBF. Observed baseline CBF decreases for HIV−/METH+ participants are less likely to be of vascular etiology as >70% stenosis of tagged feeding arteries must occur before collateral autoregu-lation cannot compensate for CBF reductions (Bokkers et al. 2009). Typically, these changes in CBF are seen after more acute use of this drug of abuse. It is quite interesting that despite a period of METH abstinence, baseline CBF and changes in CBF for the functional task did not normalize. This may represent continued irreversible neuronal dysfunction due to prior METH exposure (Chang et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2004).

Observed reductions in baseline CBF within HIV+ participants are similar to previous reports by our group and others (Ances et al. 2006, 2009; Chang et al. 2000; Pohl et al. 1988). HIV has a predilection for the LN with VL greatest in this area (Fujimura et al. 1997). The exact etiology as to why the LN is preferentially affected by HIV remains unknown but may be due to its close proximity to the ventricles and/or its high metabolic demands and sensitivity to small perturbation in metabolic activity (Ances et al. 2006). At autopsy, multinucleated giant cells, microglial nodules, and infiltrating macrophages are often observed within the LN (Nath et al. 2001; Navia et al. 1986). Our results could suggest that neuronal injury may continue to persist despite relatively good virological control (Kumar et al. 2009).

An additive effect of HIV infection and previous METH dependence has previously been observed with neuropsychological performance testing (Rippeth et al. 2004). Neuropsychological impairment rates rise with increasing number of risk factors. HIV+/METH+ participants have the greater prevalence of impairment in multiple domains compared to a single domain deficit (54% vs. 44%, χ2= 18.11, p<0.0001; Carey et al. 2006). Similar results have been seen with neuroimaging, especially magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Chang et al. 2005). This is the first study to use ASL to study the possible interaction between HIV and METH.

While the exact mechanism(s) responsible for neuronal dysfunction due to HIV and METH dependence remain unknown, common overlapping pathways may exist leading to observed changes (Langford et al. 2004). METH can cause a breakdown of the blood–brain barrier allowing for a greater trafficking of HIV infected monocytes into the brain (Ramirez et al. 2009). Both HIV and METH dependence can induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction causing dopaminergic dysfunction. Abnormal neuronal function could lower resting metabolic requirements therefore leading to a decrease in coupled baseline CBF. However, for a task, larger compensatory requirements result in greater fractional changes in CBF for the functional task. Regardless of HIV status or history of METH dependence, the same final level is reached such that in the absolute CBF levels during activation are similar. Simply looking only at the reduced fractional CBF response, one could jump to the conclusion that an altered acute response likely represents an alteration in the subject's ability to do the task. Instead, similar absolute CBF changes during the task could reflect unchanged ability to do the task. Observed difference may instead reflect the chronic effect of the disease on baseline CBF.

This study has a number of limitations. While we primarily focused on the possible effect of prior METH dependence in HIV+ and HIV− participants, we could not exclude participants based on marijuana or alcohol use as a considerable overlap exists within METH+ individuals. A significantly higher proportion of the METH+ subjects had used marijuana and alcohol heavily in the past. While this prevents us from directly ascribing our results to METH dependence alone, the inclusion of these subjects provides a more representative sample of METH users encountered in clinical settings. In an attempt to control for the possible short-term effects of substances of abuse, urine toxicology was performed prior to scanning with subjects excluded if the test was positive. In addition, other substances, such as nicotine use (Fama et al. 2009; Rosenbloom et al. 2007), were not controlled. A complex relationship has previously been seen for nicotine where recent smoking can lead to an increase in baseline CBF in the visual cortex and the cerebellum but a reduction in baseline CBF within the hippocampus and striatum (Domino et al. 2000; Zubieta et al. 2005). Future studies investigating the effects of nicotine on baseline CBF using ASL are required. In addition, the main effect associated with a previous history of chronic METH dependence is based on a relatively small group of HIV−/METH+ subjects compared to all other groups. While the small sample size somewhat tempers the generalizability of our results, significant differences were seen. Larger studies are warranted. It remains possible that observed decreases in baseline CBF seen with a previous history of METH+ dependence may not result from excessive stimulant exposure but instead could reflect increased susceptibility of these individuals to develop substance dependence. The effect of developmental abnormalities that preceded METH dependence cannot be ruled out. Within our HIV+ cohort, viral replication was relatively well suppressed (log plasma VL=2.36). We would expect that even greater adverse impact by HIV on baseline CBF would be seen for HIV+ participants with poorly controlled HIV replication. Our study has only focused on a single brain region that is highly susceptible to both HIV and METH. Future studies could include additional brain regions that are commonly affected by either METH dependence or HIV infection. Finally, only a limited number of slices were prescribed to ensure coverage of the LN. Future studies with whole brain coverage using ASL could be considered. A relative strength of this study was that in vivo quantitative measurements of the effects of HIV and METH dependence were obtained. For both baseline and a functional activation paradigm ASL measurements of CBF provided three quantitative measures (absolute baseline CBF, percent CBF change for a task, and absolute CBF during activation) compared to BOLD imaging where a single value is acquired (%BOLD for a task). Our study demonstrates that abnormalities in CBF could be a sensitive measure to study the effects of HIV and METH dependence in the brain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Dana Foundation Brain Immuno Imaging Award (DF3857-41880; B.A.) and NIH grants 1K23MH081786 and 1R01NR012657 (B.A.), NS-36722 and NS-42069 (R.B., C.G., and C.L.), MH22005 and AI47033 (F.V.), P30 MH62512 (M.C., R.E., I.G., F,V., and HNRC Group), and P01 DA12065. The authors would like to thank the contributions of study participants and staff at the HNRC and Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (P50 DA26306), San Diego, CA, USA. The HNRC Group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and includes Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and J. Allen McCutchan, M.D.; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Assistant Center Manager: Jennifer Marquie-Beck; Business Manager: Melanie Sherman; Naval Hospital San Diego: Braden R. Hale, M.D., M.P.H. (P.I.); Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Scott Letendre, M.D., Edmund Capparelli, Pharm.D., Rachel Schrier, Ph.D., and Terry Alexander, R.N.; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., Steven Paul Woods, Psy.D., David J. Moore, Ph.D.; Matthew Dawson, and Donald Franklin; Neuroimaging Component: Terry Jernigan, Ph.D. (P.I.), Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D., Sarah L. Archibald, M.A., Marc Jacobson, Ph.D., Jacopo Annese, Ph.D., and Michael J. Taylor, Ph. D.; Neurobiology Component: Eliezer Masliah, M.D. (P.I.), Ian Everall, FRCPsych., FRCPath., Ph.D., and Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; Neuro-virology Component: Douglas Richman, M.D., (P.I.) and David M. Smith, M.D.; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., (P.I.); Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, MD, Ph.D. (P.I.) and Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Clinical Trials Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M. D., J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and Scott Letendre, M.D.; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.) and Rodney von Jaeger, M.P.H.; Data Management Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.) and Clint Cushman (Data Systems Manager); Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph. D., Tanya Wolfson, MS, and Reena Deutsch, Ph.D.

Footnotes

This work was previously presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2010.

Disclaimer There are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Beau M. Ances, Email: bances@wustl.edu, Department of Neurology, Washington University in St. Louis, 660 South Euclid Ave, Box 08111, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA.

Florin Vaida, Departments of Family and Preventative Medicine, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA.

Mariana Cherner, The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA.

Melinda J. Yeh, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA

Christine L. Liang, Department of Radiology, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA

Carly Gardner, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA.

Igor Grant, The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA.

Ronald J. Ellis, The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group, Department of Neurosciences, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA

Richard B. Buxton, Department of Radiology, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA

References

- Allison JD, Meador KJ, Loring DW, Figueroa RE, Wright JC. Functional MRI cerebral activation and deactivation during finger movement. Neurology. 2000;54:135–142. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ances BM, Ellis RJ. Dementia and neurocognitive disorders due to HIV-1 infection. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:86–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ances BM, Roc AC, Wang J, Korczykowski M, Okawa J, Stern J, Kim J, Wolf R, Lawler K, Kolson DL, Detre JA. Caudate blood flow and volume are reduced in HIV+ neurocognitively impaired patients. Neurology. 2006;66:862–866. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000203524.57993.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ances BM, Leontiev O, Perthen JE, Liang C, Lansing AE, Buxton RB. Regional differences in the coupling of cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism changes in response to activation: implications for BOLD-fMRI. Neuroimage. 2008a;39:1510–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ances BM, Roc AC, Korczykowski M, Wolf RL, Kolson DL. Combination antiretroviral therapy modulates the blood oxygen level-dependent amplitude in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients. J Neurovirol. 2008b;14:418–424. doi: 10.1080/13550280802298112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ances BM, Sisti D, Vaida F, Liang CL, Leontiev O, Perthen JE, Buxton RB, Benson D, Smith DM, Little SJ, Richman DD, Moore DJ, Ellis RJ. Resting cerebral blood flow: a potential biomarker of the effects of HIV in the brain. Neurology. 2009;73:702–708. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b59a97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ances B, Vaida F, Ellis R, Buxton R. Test-retest stability of calibrated BOLD-fMRI in HIV- and HIV+ subjects. Neuroimage. 2010;54:2156–2162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford NS, Zhang H, Joyce JA, Scarlis CA, Hanan W, Wu NP, Andre VM, Cohen R, Cepeda C, Levine MS, Harleton E, Sulzer D. Repeated exposure to methamphetamine causes longlasting presynaptic corticostriatal depression that is renormalized with drug readministration. Neuron. 2008;58:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokkers RP, van der Worp HB, Mali WP, Hendrikse J. Noninvasive MR imaging of cerebral perfusion in patients with a carotid artery stenosis. Neurology. 2009;73:869–875. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b7840c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton GM, Engel SA, Glover GH, Heeger DJ. Linear systems analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging in human V1. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4207–4221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04207.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burock MA, Dale AM. Estimation and detection of event-related fMRI signals with temporally correlated noise: a statistically efficient and unbiased approach. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;11:249–260. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200012)11:4<249::AID-HBM20>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton RB. Interpreting oxygenation-based neuroimaging signals: the importance and the challenge of understanding brain oxygen metabolism. Front Neuroenergetics. 2010;2:8. doi: 10.3389/fnene.2010.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Gonzalez R, Heaton RK, Grant I. Additive deleterious effects of methamphetamine dependence and immunosuppression on neuropsychological functioning in HIV infection. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:185–190. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalela JA, Alsop DC, Gonzalez-Atavales JB, Maldjian JA, Kasner SE, Detre JA. Magnetic resonance perfusion imaging in acute ischemic stroke using continuous arterial spin labeling. Stroke. 2000;31:680–687. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chana G, Everall IP, Crews L, Langford D, Adame A, Grant I, Cherner M, Lazzaretto D, Heaton R, Ellis R, Masliah E. Cognitive deficits and degeneration of interneurons in HIV+ methamphetamine users. Neurology. 2006;67:1486–1489. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240066.02404.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, Leonido-Yee M, Speck O. Perfusion MRI detects rCBF abnormalities in early stages of HIV-cognitive motor complex. Neurology. 2000;54:389–396. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Speck O, Miller EN, Braun J, Jovicich J, Koch C, Itti L, Ernst T. Neural correlates of attention and working memory deficits in HIV patients. Neurology. 2001;57:1001–1007. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, Speck O, Patel H, DeSilva M, Leonido-Yee M, Miller EN. Perfusion MRI and computerized cognitive test abnormalities in abstinent methamphetamine users. Psychiatry Res. 2002;114:65–79. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(02)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Tomasi D, Yakupov R, Lozar C, Arnold S, Caparelli E, Ernst T. Adaptation of the attention network in human immunodeficiency virus brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:259–272. doi: 10.1002/ana.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, Speck O, Grob CS. Additive effects of HIV and chronic methamphetamine use on brain metabolite abnormalities. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:361–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Alicata D, Ernst T, Volkow N. Structural and metabolic brain changes in the striatum associated with methamphetamine abuse. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):16–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherner M, Letendre S, Heaton RK, Durelle J, Marquie-Beck J, Gragg B, Grant I. Hepatitis C augments cognitive deficits associated with HIV infection and methamphetamine. Neurology. 2005;64:1343–1347. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158328.26897.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherner M, Suarez P, Casey C, Deiss R, Letendre S, Marcotte T, Vaida F, Atkinson JH, Grant I, Heaton RK. Methamphetamine use parameters do not predict neuropsychological impairment in currently abstinent dependent adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarelli PA, Bulte DP, Piechnik S, Jezzard P. Sources of systematic bias in hypercapnia-calibrated functional MRI estimation of oxygen metabolism. Neuroimage. 2007;34:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Harezlak J, Schifitto G, Hana G, Clark U, Gongvatana A, Paul R, Taylor M, Thompson P, Alger J, Brown M, Zhong J, Campbell T, Singer E, Daar E, McMahon D, Tso Y, Yiannoutsos CT, Navia B. Effects of nadir CD4 count and duration of human immunodeficiency virus infection on brain volumes in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Neurovirol. 2010;16:25–32. doi: 10.3109/13550280903552420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino EF, Minoshima S, Guthrie S, Ohl L, Ni L, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Nicotine effects on regional cerebral blood flow in awake, resting tobacco smokers. Synapse. 2000;38:313–321. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20001201)38:3<313::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Moore DJ, Childers ME, Letendre S, McCutchan JA, Wolfson T, Spector SA, Hsia K, Heaton RK, Grant I. Progression to neuropsychological impairment in human immunodeficiency virus infection predicted by elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of human immunodeficiency virus RNA. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:923–928. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Rosenbloom MJ, Nichols BN, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Working and episodic memory in HIV infection, alcoholism, and their comorbidity: baseline and 1-year follow-up examinations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1815–1824. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora G, Lee YW, Nath A, Hennig B, Maragos W, Toborek M. Methamphetamine potentiates HIV-1 Tat protein-mediated activation of redox-sensitive pathways in discrete regions of the brain. Exp Neurol. 2003;179:60–70. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura RK, Goodkin K, Petito CK, Douyon R, Feaster DJ, Concha M, Shapshak P. HIV-1 proviral DNA load across neuroanatomic regions of individuals with evidence for HIV-1-associated dementia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;16:146–152. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199711010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL, Gamst AC, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Mindt MR, Marcotte TD, Heaton RK, Ellis RJ, Grant I. Effects of methamphetamine dependence and HIV infection on cerebral morphology. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1461–1472. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengst SB, Aizenstein HJ, Figurski J, Lopez OL, Becker JT. Alterations in the hemodynamic response function in cognitively impaired HIV/AIDS subjects. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;163:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrup A, Kruger G, Neumann-Haefelin T, Glover GH, Moseley ME. Changes of cerebral blood flow, oxygenation, and oxidative metabolism during graded motor activation. Neuroimage. 2002;15:74–82. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AM, Fernandez J, Singer EJ, Commins D, Waldrop-Valverde D, Ownby RL, Kumar M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the central nervous system leads to decreased dopamine in different regions of postmortem human brains. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:257–274. doi: 10.1080/13550280902973952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford D, Grigorian A, Hurford R, Adame A, Crews L, Masliah E. The role of mitochondrial alterations in the combined toxic effects of human immunodeficiency virus Tat protein and methamphetamine on calbindin positive-neurons. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:327–337. doi: 10.1080/13550280490520961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JF, O'Dell SJ, Weihmuller FB. Dopamine-glutamate interactions in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;91:241–254. doi: 10.1007/BF01245234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumford JA, Hernandez-Garcia L, Lee GR, Nichols TE. Estimation efficiency and statistical power in arterial spin labeling fMRI. Neuroimage. 2006;33:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A, Maragos WF, Avison MJ, Schmitt FA, Berger JR. Acceleration of HIV dementia with methamphetamine and cocaine. J Neurovirol. 2001;7:66–71. doi: 10.1080/135502801300069737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navia BA, Cho ES, Petito CK, Price RW. The AIDS dementia complex: II. Neuropathology. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:525–535. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa A, Maeshima S, Shimamoto Y, Maeshima E, Sekiguchi E, Kakishita K, Ozaki F, Moriwaki H. Relationship between cognitive function and regional cerebral blood flow in different types of dementia. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:739–745. doi: 10.1080/09638280410001704331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perthen JE, Bydder M, Restom K, Liu TT. SNR and functional sensitivity of BOLD and perfusion-based fMRI using arterial spin labeling with spiral SENSE at 3 T. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008a;26:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perthen JE, Lansing AE, Liau J, Liu TT, Buxton RB. Caffeine-induced uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism: a calibrated BOLD fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2008b;40:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl P, Vogl G, Fill H, Rossler H, Zangerle R, Gerstenbrand F. Single photon emission computed tomography in AIDS dementia complex. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:1382–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez SH, Potula R, Fan S, Eidem T, Papugani A, Reichenbach N, Dykstra H, Weksler BB, Romero IA, Couraud PO, Persidsky Y. Methamphetamine disrupts blood-brain barrier function by induction of oxidative stress in brain endothelial cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1933–1945. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restom K, Perthen JE, Liu TT. Calibrated fMRI in the medial temporal lobe during a memory-encoding task. Neuroimage. 2008;40:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Carey CL, Marcotte TD, Moore DJ, Gonzalez R, Wolfson T, Grant I. Methamphetamine dependence increases risk of neuropsychological impairment in HIV infected persons. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704101021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom MJ, Sullivan EV, Sassoon SA, O'Reilly A, Fama R, Kemper CA, Deresinski S, Pfefferbaum A. Alcoholism, HIV infection, and their comorbidity: factors affecting self-rated health-related quality of life. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:115–125. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, Meyer RA, Heaton RK, Atkinson JH, Grant I. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17:275–297. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SL, Dean AC, Cordova X, Monterosso JR, London ED. Methamphetamine dependence and neuropsychological functioning: evaluating change during early abstinence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:335–344. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephans SE, Yamamoto BK. Methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity: roles for glutamate and dopamine efflux. Synapse. 1994;17:203–209. doi: 10.1002/syn.890170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki M, Ujike H, Kodama M, Takehisa Y, Yamamoto A, Kuroda S. Increased expression of synaptophysin and stathmin mRNAs after methamphetamine administration in rat brain. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1055–1060. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200104170-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MJ, Schweinsburg BC, Alhassoon OM, Gongvatana A, Brown GG, Young-Casey C, Letendre SL, Grant I. Effects of human immunodeficiency virus and methamphetamine on cerebral metabolites measured with magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurovirol. 2007;13:150–159. doi: 10.1080/13550280701194230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafaee MS, Gjedde A. Spatially dissociated flow-metabolism coupling in brain activation. Neuroimage. 2004;21:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Chang L, Volkow ND, Telang F, Logan J, Ernst T, Fowler JS. Decreased brain dopaminergic transporters in HIV-associated dementia patients. Brain. 2004;127:2452–2458. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang Y, Wolf RL, Roc AC, Alsop DC, Detre JA. Amplitude-modulated continuous arterial spin-labeling 3.0-T perfusion MR imaging with a single coil: feasibility study. Radiology. 2005;235:218–228. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2351031663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westover AN, McBride S, Haley RW. Stroke in young adults who abuse amphetamines or cocaine: a population-based study of hospitalized patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:495–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Heitzeg MM, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, Ni L, Guthrie S, Domino EF. Regional cerebral blood flow responses to smoking in tobacco smokers after overnight abstinence. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:567–577. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]