Abstract

DNA-based stable-isotope probing was applied to identify the active microorganisms involved in syntrophic butyrate oxidation in paddy field soil. After 14 and 21 days of incubation with [U-13C]butyrate, the bacterial Syntrophomonadaceae and the archaeal Methanosarcinaceae and Methanocellales incorporated substantial amounts of 13C label into their nucleic acids. Unexpectedly, members of the Planctomycetes and Chloroflexi were also labeled with 13C by yet-unclear mechanisms.

TEXT

Butyrate is one of the important intermediates in the degradation of organic matter in anoxic environments (3–5, 22). The degradation of butyrate to H2, formate, and acetate is endergonic under standard conditions. This thermodynamic barrier, however, can be overcome by the syntrophic interaction between butyrate-oxidizing bacteria and methanogenic archaea, which keep the products H2, formate, and acetate at low concentrations (23). A few strains involved in syntrophic butyrate oxidation have been isolated into pure cultures (e.g., see references 15, 16, and 30). These organisms represent a thermodynamically extreme lifestyle, since even in the optimum syntrophic association with methanogens, the Gibbs free energy available for syntrophic butyrate oxidizers is still close to the thermodynamic limit (ΔG0′ = −20 kJ per reaction). Recently, genome sequences of two syntrophic butyrate oxidizers (Syntrophomonas wolfei and Syntrophus aciditrophicus) (17, 24) revealed that they have limited fermentation and respiration mechanisms but possess multiple copies of β-oxidation genes and sets of reverse electron transfer machineries which are essential for the syntrophic oxidation of butyrate.

Studies on natural environments, however, are very scarce (1, 5). Acetate, propionate, and butyrate are the most important intermediates during the degradation of organic residues in paddy field soils (4, 22). Only two studies known to us so far, however, have been conducted to determine the syntrophic degradation of propionate (12) and acetate (7), and none have been done on syntrophic butyrate oxidation in paddy field soil. Therefore, our objectives were to investigate syntrophic butyrate oxidation and identify the active organisms responsible for this process in a Chinese paddy field soil using nucleic acid-based stable-isotope probing (SIP), which has been proven to be powerful in linking the identities of microorganisms in environments with their specific functions (2).

Soil sample and anoxic incubation.

Paddy field soil was collected from an experimental station of the China National Rice Research Institute in Hangzhou, China (30°04′37″N, 119°54′37″E). The soil was a clay loam and had the following properties as measured by standard methods (18): pH 6.7, a cation exchange capacity of 14.4 cmol kg−1, an organic C content of 24.2 g kg−1, and a total N content of 2.3 g kg−1. Soil was air dried and passed through 2-mm sieves. Three-gram soil samples were weighed in 15-ml serum bottles and mixed with 4.5 ml distilled anoxic water. The vials were closed with butyl rubber septa and flushed with a pure N2 stream for 5 min. Soil slurries were then anaerobically preincubated in the dark at 25°C for 21 days. According to our previous studies with the same soil (28, 29), oxidants other than CO2 were reduced, and a quasi-steady state of methanogenesis was established after 21 days of preincubation. Fully 13C-labeled sodium butyrate (99 atom%; Sigma-Aldrich) was added three times, specifically, on day 1, day 7, and day 16 after preincubation (each time to a final concentration of 5.0 mM in soil pore water). A parallel set of incubations containing nonlabeled butyrate was prepared as a control. The incubations were carried out in triplicate.

Conversion of [13C]butyrate to CH4 and CO2.

Gas samples (0.2 ml) were collected from headspaces with a syringe every 2 to 4 days. Total concentrations of CH4 and CO2 were analyzed using a gas chromatograph (Shanghai Precision and Scientific Instrument Co., China) (19), and 13C/12C isotope ratios were determined using a gas chromatograph-isotope ratio mass spectrometry system (20). Liquid samples (0.5 ml) were taken with a sterile syringe, centrifuged, and filtered through 0.22-μm filters. Acetate and butyrate concentrations were analyzed with an HP 6890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies) as described previously (19).

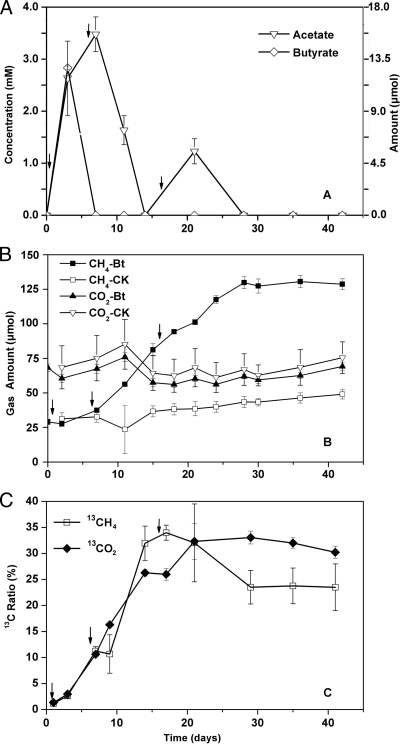

The concentration of butyrate added was over an order of magnitude higher than that commonly observed in paddy field soil. However, if rice straw was incorporated into the soil, butyrate could transiently accumulate up to a concentration of 10 mM in soil pore water (3). The maximal concentration detected in the soil slurry was 2.8 mM at day 3 after butyrate addition (Fig. 1A). Later on, butyrate was degraded rapidly and the concentrations decreased to near the detection limit (<40 μM). Acetate accumulated to a maximum of 3.5 mM at day 8 (just 1 day after the second addition of butyrate), followed by a rapid decrease and a slight increase again after the third addition of butyrate.

Fig. 1.

Dynamics of short-chain fatty acids, headspace gas abundance, and 13C ratios during the incubation. (A) Butyrate and acetate concentrations in the soil solution after the addition of sodium butyrate. (B) CH4 and CO2 concentrations in the headspace during the whole incubation period. Bt, with addition of sodium butyrate; CK, control check, without butyrate addition. (C) Dynamics of the 13CH4 and 13CO2 atom ratio (percentages) in the headspace after addition of a 13C-labeled substrate. Arrows in the figure indicate the time points of butyrate addition. Data are means ± standard errors (n = 3 for panels A and B; n = 2 for panel C).

The addition of butyrate stimulated CH4 production (Fig. 1B). The CH4 concentration in the headspace reached 130 μmol at day 28 and leveled off thereafter. The CO2 concentration also increased after butyrate addition but more slowly than the CH4 concentration.

Syntrophic butyrate oxidation was evidenced with the increase of 13CH4 and 13CO2 after the addition of [13C]butyrate (Fig. 1C). The 13C atom% reached a maximum of 34% for CH4 at day 17 (1 day after the third addition of butyrate) and 33% for CO2 at day 21. In total, 67.5 μmol of [13C]butyrate were applied to the soil slurry in each incubation. Based on the concentrations of total CH4 and 13CH4 in the headspace, we estimated that ∼90 μmol of 13CH4 was produced from butyrate, which corresponded to ∼54% of the amounts expected from stoichiometric calculations (23).

Resolving active organisms by DNA-SIP.

Three soil samples were used for DNA-SIP analysis: (i) labeled soil collected on day 14, (ii) labeled soil collected on day 21, and (iii) control soil collected on day 21 (with the addition of nonlabeled butyrate). The genomic DNA was extracted from about 0.5 g of fresh soil using a FastDNA Spin kit (MP Biomedicals, LLC). Density gradient centrifugation was performed by following the protocol by Lu and coworkers (9), with a few modifications. Briefly, centrifugation medium consisting of 5.0 ml of 2.0-g ml−1 cesium trifluoroacetate (CsTFA) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 3.9 ml of gradient buffer (GB; 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM EDTA), and up to 3 μg of nucleic acid extracts were placed in 8.9-ml polyallomer UltraCrimp tubes and spun in a Ti90 vertical rotor (Beckman) at 177,000 × g and 20°C for >36 h using a Beckman Optima 2-80XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Density gradient DNA was then fractionated according to the protocols of references 8, 9, and 11. For terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis, the density-resolved DNA fractions were PCR amplified using the primer pairs Ba27f/Ba907r for bacteria and Ar109f/Ar934r for archaea (11), with Ba27f and Ar934r labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM). The PCR products were digested with MspI (Takara) for bacteria and TaqI (Takara) for archaea, and the digestion products were size separated with a model 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) by following the procedure described previously (19, 22).

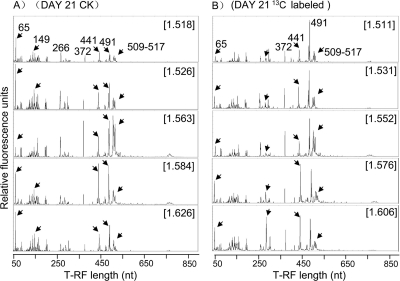

The T-RFLP patterns of the control soil did not differ significantly among different buoyant density (BD) fractions, except that there were a few inconsistent variations among the T-RFLP patterns of the 266-bp, 509-bp, and 517-bp T-RFs (Fig. 2A). For the labeled soil at day 14 (data not shown), T-RFLP patterns did not differ in the “light” fractions (BD ≤ 1.563 g ml−1), but with an increase in BD, the fluorescent intensities of T-RFs of 65, 291, and 441 bp markedly increased, while that of the 266-bp T-RF relatively decreased. For the labeled soil at day 21 (Fig. 2B), a similar tendency was observed; i.e., T-RFLP patterns remained similar in the light fractions with BDs of ≤1.552 g ml−1, while the intensities of the 65-bp, 291-bp, and 441-bp T-RFs in the “heavy” fractions substantially increased. Some T-RFs, like those of 489 bp, 491 bp, and 372 bp, were dominant in all T-RFLP profiles but did not show consistent changes in either labeled or nonlabeled samples.

Fig. 2.

T-RFLP fingerprints of density-resolved bacterial communities generated from selected 16S rRNA gene gradient fractions. (A) Nonlabeled DNA sample of day 21; (B) 13C-labeled DNA sample of day 21. Cesium trifluoroacetate BDs (g ml−1) of gradient fractions are given in brackets. The specific fragment lengths (in base pairs) of important T-RFs (as mentioned in the text) are given, and T-RFs with obvious changes are marked with short arrows.

Two bacterial clone libraries were constructed from a heavy DNA (D21H4, BD = 1.610 g ml−1) and a light DNA (D21L12, BD = 1.508 g ml−1) gradient fraction obtained from the labeled sample at day 21. These fractions represented the heaviest and lightest DNAs resolved by CsTFA isopycnic centrifugation (9). PCR was performed as described above with the bacterial primers without FAM labeling. PCR products were purified, cloned into Escherichia coli cells, and sequenced with an ABI 3730xl sequencer as described before (Applied Biosystems) (19, 22).

Phylogenetic analysis of 158 clone sequences by the ARB software package (http://www.arb-home.de) (10) using the neighbor-joining algorithm revealed that the bacterial community in the soil was dominated by Clostridia, Gammaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Planctomycetes, and other phylogenetic groups, like Bacteroidetes, Chlorobi, and Acidobacteria (Table 1). The heavy-clone library contained relatively more sequences of Planctomycetes, Chloroflexi, and Chlorobi than the light-clone one. Syntrophomonas spp. were not dominant, but three clones and one clone were detected in the heavy and light libraries, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phylogenetic affiliations and numbers of bacterial 16S rRNA gene clones retrieved in libraries generated from density-resolved nucleic acids collected from the labeled soil on day 21

| Phylogenetic group | No. of clonesa |

Characteristic T-RF length(s) (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D21H4 heavy | D21L12 light | ||

| Betaproteobacteria | 2 | 3 | 491 |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 12 | 11 | 117, 305, 489 |

| Alphaproteobacteria | 6 | 11 | 149, 441 |

| Deltaproteobacteria | 3 | 1 | 125 |

| Bacteroidetes | 2 | 2 | 85, 90 |

| Chlorobi | 7 | 3 | 372 |

| Planctomycetes | 10 | 6 | 65, 161 |

| Acidobacteria | 2 | 3 | 138, 471 |

| Firmicutes | 19 | 20 | |

| Bacilli | 1 | 0 | 162 |

| Clostridia | 18 | 20 | 165, 206, 266, 509, 512, 517 |

| Syntrophomonas spp. | 3 | 1 | 291 |

| Actinobacteria | 4 | 8 | 270 |

| Chloroflexi | 9 | 1 | Diverse |

| Deinococcus-Thermus | 0 | 3 | 166 |

| OP10 | 3 | 1 | 303 |

| OP5 | 1 | 0 | 279 |

| WS1 | 0 | 1 | 285 |

| Unclassified bacteria | 2 | 1 | None |

| Total | 82 | 76 | |

D21H4 and D21L12, samples collected on day 21 (H4, BD = 1.610 g ml−1; L12, BD = 1.508 g ml−1). Heavy (H) and light (L), the heaviest and lightest fractions in terms of 13C enrichment of bacterial rRNA genes.

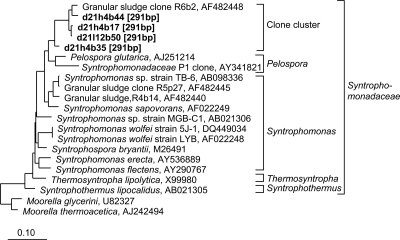

The in silico analysis of clone sequences indicated that the 291-bp T-RF which increased in the heavy-DNA fractions could be assigned to Syntrophomonas spp. (Fig. 3). Thus, these organisms assimilated 13C into their nucleic acids during anaerobic incubation. Syntrophomonadaceae are known as typical syntrophic butyrate oxidizers in anoxic environments (15, 16). Four clones affiliated with this group, however, showed a 16S rRNA similarity of only 95% to the closest pure culture, Pelospora glutarica (14), and 94% to Syntrophomonas sapovorans (21, 30) (Fig. 3) and thus possibly represent a new species or genus.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship of representative sequences related to Syntrophomonas spp. Clone libraries were generated from density-resolved 16S rRNA genes of anoxic rice soil organisms after incubation with [13C]butyrate for 21 days. d21h or d21l, day 21 heavy or light DNA fractions, respectively. Numbers in parentheses (base pairs) indicate in silico T-RF sizes. The scale bar represents 10% sequence divergence. GenBank accession numbers of reference sequences are given.

The 441-bp T-RF represented mainly the alphaproteobacteria, which include Defluvicoccus, Bradyrhizobiaceae, Rhodomicrobium, Brevundimonas, and Sphingomonas. This T-RF increased with BD for not only the labeled sample but also the nonlabeled one (Fig. 2), thus reflecting the influence of other factors, like GC content, rather than 13C incorporation. Some pure cultures of Defluvicoccus indeed had a high GC content (13).

Unexpectedly, the 65-bp T-RF, which also increased with the BD of DNA, was affiliated mainly with Planctomycetes (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In addition, the Chloroflexi members, albeit not represented by a single T-RF (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), were more prevalent in the heavy-clone library than in the light-clone one (Table 1). The mechanism for the 13C labeling of Chloroflexi and Planctomycetes currently remains unclear. These organisms are not known to syntrophically oxidize butyrate. It has been shown, however, that some of the Anaerolineae within the Chloroflexi (Fig. S3) fermented various sugars and grew better in the presence of H2-consuming methanogens, hinting at a syntrophic metabolism (26, 27). Alternatively, it is possible that Chloroflexi and Planctomycetes assimilated [13C]acetate produced intermediately during the butyrate degradation. A previous study showed that some anaerobes, like Geobacter spp. and Anaeromyxobacter spp., assimilated acetate under methanogenic conditions (6). Resolving the nature of the apparent labeling of Chloroflexi and Planctomycetes requires further investigations.

T-RFLP fingerprints from the archaeal community for the labeled sample at day 21 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) revealed that the 187-bp T-RF and the 394-bp T-RF significantly increased with the BD of DNA, reaching 59% and 28% of the community, respectively, at a BD of 1.590 g ml−1. These T-RFs represented Methanosarcinaceae and Methanocellales, respectively, according to our previous studies in the same soil (19, 25, 26, 29). Apparently, these organisms served as acetate and H2 scavengers during the syntrophic oxidation of butyrate in the soil.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated the key role of Syntrophomonadaceae, Methanosarcinaceae, and Methanocellales in the syntrophic oxidation of butyrate in paddy field soil. In addition, some other organisms, like Chloroflexi and Planctomycetes, might also assimilate butyrate-derived carbon by yet-unclear mechanisms.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The partial 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers FR687044 to FR687199.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ralf Conrad for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which improved the paper.

This study was partially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 40625003 and 40830534) and the Chang Jiang Scholars Program of the Chinese Ministry of Education. P.L. received a scholarship from the Graduate School of China Agricultural University.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 1 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chauhan A., Ogram A. 2006. Fatty acid-oxidizing consortia along a nutrient gradient in the Florida everglades. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2400–2406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dumont M. G., Murrell J. C. 2005. Stable isotope probing—linking microbial identity to function. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glissmann K., Conrad R. 2000. Fermentation pattern of methanogenic degradation of rice straw in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 31:117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glissmann K., Conrad R. 2002. Saccharolytic activity and its role as a limiting step in methane formation during the anaerobic degradation of rice straw in rice paddy soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 35:62–67 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hatamoto M., Imachi H., Yashiro Y., Ohashi A., Harada H. 2008. Detection of active butyrate-degrading microorganisms in methanogenic sludges by RNA-based stable isotope probing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3610–3614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hori T., Noll M., Igarashi Y., Friedrich M., Conrad R. 2007. Identification of acetate-assimilating microorganisms under methanogenic conditions in anoxic rice field soil by comparative stable isotope probing of RNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:101–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu F. H., Conrad R. 2010. Thermoanaerobacteriaceae oxidize acetate in methanogenic rice field soil at 50°C. Environ. Microbiol. 12:2341–2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu Y. H., Conrad R. 2005. In situ stable isotope probing of methanogenic archaea in the rice rhizosphere. Science 309:1088–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lu Y., Lueders T., Michael W., Friedrich M. W., Conrad R. 2005. Detecting active methanogenic populations on rice roots using stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 7:326–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ludwig W., et al. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lueders T., Manefield M., Friedrich M. W. 2004. Enhanced sensitivity of DNA- and rRNA-based stable isotope probing by fractionation and quantitative analysis of isopycnic centrifugation gradients. Environ. Microbiol. 6:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lueders T., Pommerenke B., Friedrich M. W. 2004. Stable-isotope probing of microorganisms thriving at thermodynamic limits: syntrophic propionate oxidation in flooded soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5778–5786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maszenan A. M., Seviour R. J., Patel B. K., Janssen P. H., Wanner J. 2005. Defluvicoccus vanus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel Gram-negative coccus/coccobacillus in the ‘Alphaproteobacteria’ from activated sludge. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:2105–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matthies C., Springer N., Ludwig W., Schink B. 2000. Pelospora glutarica gen. nov., sp nov., a glutarate-fermenting, strictly anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:645–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McInerney M. J., Bryant M. P., Hespell R. B., Costerton J. W. 1981. Syntrophomonas wolfei gen. nov. sp. nov., an anaerobic, syntrophic, fatty acid-oxidizing bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:1029–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McInerney M. J., Bryant M. P., Pfennig N. 1979. Anaerobic bacterium that degrades fatty-acids in syntrophic association with methanogens. Arch. Microbiol. 122:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McInerney M. J., et al. 2007. The genome of Syntrophus aciditrophicus: life at the thermodynamic limit of microbial growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7600–7605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Page A. L., Miller R. H., Keeney D. R. 1982. Methods of soil analysis. Part 2. Chemical and microbiological properties, 2nd ed American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peng J., Lu Z., Rui J., Lu Y. 2008. Dynamics of the methanogenic archaeal community during plant residue decomposition in an anoxic rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2894–2901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qiu Q., Noll M., Abraham W. R., Lu Y., Conrad R. 2008. Applying stable isotope probing of phospholipid fatty acids and rRNA in a Chinese rice field to study activity and composition of the methanotrophic bacterial communities in situ. ISME J. 2:602–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roy F., Samain E., Dubourguier H. C., Albagnac G. 1986. Synthrophomonas sapovorans sp. nov., a new obligately proton reducing anaerobe oxidizing saturated and unsaturated long chain fatty acids. Arch. Microbiol. 145:142–147 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rui J., Peng J., Lu Y. 2009. Succession of bacterial populations during plant residue decomposition in rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4879–4886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schink B. 1997. Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:262–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sieber J. R., et al. 2010. The genome of Syntrophomonas wolfei: new insights into syntrophic metabolism and biohydrogen production. Environ. Microbiol. 12:2289–2301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu L. Q., Ma K., Li Q., Ke X. B., Lu Y. H. 2009. Composition of archaeal community in a paddy field as affected by rice cultivar and N fertilizer. Microb. Ecol. 58:819–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yabe S., Aiba Y., Sakai Y., Hazaka M., Yokota A. 2010. Thermosporothrix hazakensis gen. nov., sp nov., isolated from compost, description of Thermosporotrichaceae fam. nov within the class Ktedonobacteria Cavaletti et al. 2007 and emended description of the class Ktedonobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60:1794–1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamada T., et al. 2007. Bellilinea caldifistulae gen. nov., sp nov and Longilinea arvoryzae gen. nov., sp nov., strictly anaerobic, filamentous bacteria of the phylum Chloroflexi isolated from methanogenic propionate-degrading consortia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:2299–2306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yuan Q. A., Lu Y. H. 2009. Response of methanogenic archaeal community to nitrate addition in rice field soil. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1:362–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yuan Y. L., Conrad R., Lu Y. H. 2009. Responses of methanogenic archaeal community to oxygen exposure in rice field soil. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1:347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang C., Liu X., Dong X. 2004. Syntrophomonas curvata sp. nov., an anaerobe that degrades fatty acids in co-culture with methanogens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:969–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.