Abstract

Background

The diversity of the U.S. population and disparities in the burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) require that public health education strategies must target women and racial/ethnic minority groups to reduce their CVD risk factors, particularly in high-risk communities, such as women with the metabolic syndrome (MS).

Methods

The data reported here were based on a cross-sectional face-to-face survey of women recruited from four participating sites as part of the national intervention program, Improving, Enhancing and Evaluating Outcomes of Comprehensive Heart Care in High-Risk Women. Measures included baseline characteristics, sociodemographics, CVD related-knowledge and awareness, and Framingham risk score (FRS).

Results

There were 443 of 698 women (63.5%) with one or more risk factors for the MS: non-Hispanic white (NHW), 51.5%; non-Hispanic black (NHB), 21.0%; Hispanic, 22.6%. Greater frequencies of MS occurred among Hispanic women (p<0.0001), those with less than a high school education (70.0%) (p<0.0001), Medicaid recipients (57.8%) (p<0.0001), and urbanites (43.3%) (p<0.001). Fewer participants with MS (62.6%) knew the leading cause of death compared to those without MS (72.1%) (p<0.0001). MS was associated with a lack of knowledge of the composite of knowing the symptoms of a heart attack plus the need to call 911 (odds ratio [OR] 0.41, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.17-0.97, p=0.04).

Conclusions

Current strategies to decrease CVD risk are built on educating the public about traditional factors, including hypertension, smoking, and elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). An opportunity to broaden the scope for risk reduction among women with cardiometabolic risk derives from the observation that women with the MS have lower knowledge about CVD as the leading cause of death, the symptoms of a heart attack, and the ideal option for managing a CVD emergency.

Introduction

Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities are well documented as risks for many health conditions.1 Marked differences in the rates of cardiovascular disease (CVD) are found across racialethnic and socioeconomic status (SES) in the United States.2–4 The metabolic syndrome (MS) is a recognizable cluster of risk factors associated in combination and independently with increased risk for CVD.5,6 The racial and ethnic diversity of the United States and the current distribution of disadvantage suggest that different risk patterns for the MS exist7,8 and that targeting interventions that address the underlying factors for the MS may reduce the risk for CVD.9,10 Additionally, because the MS and its underlying defining risks are associated with the development of CVD, identifying social patterns in risk may assist in targeting strategies to address and reduce disparities.

The hypothesis of the overall Improving, Enhancing and Evaluating Outcomes of Comprehensive Heart Care in High-Risk Women program was that comprehensive CVD prevention implemented by women's heart programs in concert with local communities would attain the goals of Healthy People 2010 by providing screening and education, increasing knowledge and awareness of heart disease and its attendant risk factors, reducing cardiovascular risk, and tracking and evaluating outcomes (www.health.gov/healthypeople).11,12 Heart disease prevention activities were built around participant education and implementation of Evidence-Based Guidelines for Heart Disease Prevention in Women.13 This report examines the baseline clinical characteristics, socioeconomics, and anthropometrics of participants and explores the relation between cardiometabolic risk factors, race/ethnicity, SES, and level of education. Moreover, the study sought to document the extent of CVD knowledge and awareness among women with cardiometabolic risks and if such women are aware of options for managing an acute CVD emergency. The objective was that high-risk women should be targeted to learn important CVD facts and recognize how to manage steps in a cardiac emergency in order to reduce the potential for morbidity and mortality.

Materials and Methods

Performance sites

The data reported here were derived from the baseline information from a cross-sectional, interviewer-assisted, face-to-face questionnaire of study participants recruited in the multicenter program, Improving, Enhancing and Evaluating Outcomes of Comprehensive Heart Care in High-Risk Women, sponsored by the Office on Women's Health, United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS OWH). The DHHS OWH provided competitive awards to six women's heart centers, of which four collected data to stratify study participants for the MS according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) (NCEP ATP III) guidelines.14 The four sites were Christ Community Health Services, The Heart of Woman Program, Memphis, Tennessee (Site A); Women's Cardiovascular Medicine Program at the Center for Women's Health, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York (Site B); Enhanced-Women's Heart Advantage Program at Yale New Haven Hospital, New Haven, Connecticut (Site C); and University of California, Davis, Women's Cardiovascular Medicine Program, Sacramento, California (Site D). Two sites did not collect data, such as waist size, required to meet the criteria for the MS and could not be included. The overall outcomes, methods, and materials have been described previously.15,16

Data source

The Institutional Review Board of each organization approved the study, and all participants provided informed written consent. In accord with a data sharing and use agreement, investigators agreed to share findings for the overall analysis and other outcomes. Data were entered into individual site databases and uploaded to the Data Coordinating Center at the University of California, Davis, using numeric identifiers for participants and defined templates and data definitions. A plan for this substudy analysis received approval from the DHHS OWH and the participating sites.

Participants

Participants were screened and enrolled between January 2006 and June 2007, and baseline evaluations were completed by June 2008. Before launch of the community-based educational intervention, participants were queried via a standardized interviewer-assisted face-to-face questionnaire. Clinical characteristics (age, current/ever diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, overweight and obesity) were collected. Sociodemographic data (race, ethnicity, education, geographic area of residence, health insurance) also were collected.17

Measures

Physical measures, including blood pressure, waist circumference, height, and weight, as well as laboratory data, including fasting glucose and lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides [TG], and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C] were determined. The MS was defined according to the NCEP ATP III guidelines requiring three or more of the following: waist >35 inches, fasting glucose ≥110 mg/dL, TG ≥150 mg/dL, HDL-C<50 mg/dL, blood pressure ≥130/≥ 85 mm Hg.14 Study participants were classified for the MS by physical examination (waist size, blood pressure) and laboratory determination (fasting glucose, TG, HDL-C).

Race/ethnicity

Race and ethnicity were defined by self-identification modeled after the U.S. Census.18 Data from racial/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic white (NHW), non-Hispanic black (non-NHB), and Hispanic were collected but excluded from analyses related to race/ethnicity because the sample size was small.

Education

Education was categorized as: never attended school, attended only kindergarten, grades 1–8 (elementary), grades 9–11 (some high school), grade 12 or attained a graduate educate degree (high school graduate), college 1–3 years (some college, vocational, or technical school), college graduate, or postgraduate (>4 years of college).

Residence and insurance

Suburban or urban geographic residency was determined. Health insurance status was categorized as Medicaid or state, Medicare, health maintenance organization (HMO), private, commercial, none, or other.

Framingham Risk Score

CVD risk was determined using the Framingham Risk Score (FRS).19 Study participants were stratified into 10-year event risk categories. Low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk status were defined as <10%, 10%–20%, and >20% probability of a coronary heart disease (CHD) event in 10 years, based on the FRS algorithm.19 FRS was calculated for each subject using age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), hypertension, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and tobacco smoking as defined by the risk calculator.20 Study participants with diabetes were assigned to high-risk status21, in accord with the FRS guidelines, those with a prior CVD event or stroke were not included in the analysis.

Questions to assess awareness and knowledge

Each participant's knowledge and awareness were assessed by questions about (1) knowledge of the leading cause of death among women, (2) knowledge of the early symptoms and signs of heart attack and stroke, and (3) awareness of the action to take if experiencing a heart attack or stroke (i.e., to call 911). These questions evaluate goals established by the American Heart Association and Healthy People 2010 to improve cardiovascular health and quality of life through prevention, detection, and treatment of risk factors.11,22

Statistical analysis

The results are reported as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables (age and body mass index [BMI]) and as frequencies for categorical variables (race/ethnicity, education, residence, income and health insurance, components of cardiometabolic risk and MS, FRS, and CVD knowledge and awareness). Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to test the associations among age, race/ethnicity, education, insurance, and location of residence with the odds ratio (OR) for the MS. Similar analyses were performed assessing the effect of these variables on the odds of having high FRS and the association between MS knowledge and awareness. Indicator variables for each center were included in all models to account for differences among centers. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Study participants

There were 698 women enrolled; of these, 443 (63.5%) were classified for the presence or absence of metabolic risk. They ranged in age from 20 to 86 years (mean 55.1±11.5 years); 32.3% were 20–50 years, 37.5% were 51–60 years, and 30.3% were >60 years (Table 1). Race and ethnic information was available in 98.9% (438 of 443), and almost 44% were minority women: NHW, 51.5%; NHB, 21.0%; Hispanic, 22.6%; and other, 3.8% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Participants (n=443) | Total subjects % | Site A % | Site B % | Site C % | Site D % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age: years (range) | 55.1 (20–86) | 51.5 (20–76) | 57.7 (21–84) | 53.9 (35–82) | 52.8 (21–86) |

| <20–50 | 32.3 | 42.2 | 21.2 | 39.7 | 40.0 |

| 51–60 | 37.5 | 27.3 | 36.4 | 35.9 | 45.2 |

| 61–86 | 30.3 | 30.3 | 42.4 | 24.4 | 14.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 51.5 | 0 | 38.6 | 69.5 | 69.5 |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 21.0 | 100 | 10.3 | 19.1 | 16.8 |

| Hispanic | 22.6 | 0 | 42.9 | 11.5 | 6.3 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, other | 3.8 | 0 | 8.1 | 0 | 2.1 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 |

| Education | |||||

| Some high school or less | 15.8 | 18.2 | 27.7 | 6.9 | 4.2 |

| High school graduate | 17.2 | 51.5 | 10.3 | 22.1 | 11.6 |

| Some college, vocational, or technical school | 21.2 | 18.2 | 12.5 | 28.2 | 29.5 |

| College graduate | 14.7 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 17.6 | 24.2 |

| Postgraduate | 23.7 | 3.0 | 28.8 | 25.2 | 19.0 |

| Unknown/missing | 7.5 | 0 | 12.0 | 0 | 11.6 |

| Geographic area of residence | |||||

| Suburban | 22.1 | 0 | 23.9 | 41.2 | 0 |

| Urban | 77.2 | 100 | 74.5 | 58.8 | 100 |

| Unknown/missing | 0.7 | 0 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Health insurance status | |||||

| Medicaid or state | 24.6 | 27.2 | 47.8 | 9.2 | N/A |

| Medicare | 6.8 | 33.3 | 0 | 14.5 | N/A |

| HMO, private pay, or other commercial | 43.8 | 9.1 | 51.6 | 73.8 | N/A |

| None | 2.3 | 18.2 | 0 | 3.1 | N/A |

| Other | 0.7 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Unknown/missing | 21.9 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 0 | 100 |

| Socioeconomic status (income/year) | |||||

| Up to $19,999 | 30.0 | 87.9 | 48.1 | 13.2 | N/A |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 5.6 | 12.1 | 0 | 17.4 | N/A |

| $40,000–$74,999 | 28.4 | 0 | 51.9 | 25.6 | N/A |

| ≥$75,000 | 12.0 | 0 | 0 | 43.8 | N/A |

| Unknown/missing | 23.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

N/A, not available.

Education

Educational attainment of 410 study participants (92.6%) was less than high school to high school graduate, 33.0%; some college to college graduate, 35.9%; and postgraduate, 23.7% (Table 1).

Residence, insurance, and income

Area of residence, available for 440 study participants (99.3%), was primarily urban, 77.2% (Table 1). Health insurance for 346 women (78.1%) included Medicaid or Medicare, 31.4%; HMO, private pay, or other commercial, 43.8%; no insurance, 2.3%; and other, 0.7%. Income available for 337 women (76.1%) was ≤$19,999 (30.0%), $20,000–$39.999 (5.6%), $40,000–$74.999 (28.4%), and ≥$75, 000 (12.0%).

Frequency of MS

Components of cardiometabolic risk and the MS were evaluated: 19.6% of study participants had no components, 24.4% had one component, 17.4% had two components, and 38.6% had three or more components (Table 2). The most frequent abnormal criteria were waist circumference ≥35 inches (56.0%), elevated blood pressure (48.5%), low HDL-C (35.0%), abnormal glucose levels (26.2%), and elevated TG (25.1%). Overall, the BMI was 30.9 kg/m2, and the average BMI was either in the overweight or obese category at each individual site (Table 2). The TG level was significantly higher for those with waist ≥35 inches (139±84 vs. 95±47 mg/dL) (p<0.0001). Elevated TG, as a component of the MS, was present in 34% with waist ≥35 inches and in 13% with waist circumference <35 inches, (p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular Risk Profile of Participants

| Characteristic (risk variable) | Total cohort % | Site A % | Site B % | Site C % | Site D % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Framingham Risk Category | |||||

| Low (<10% 10-year risk) | 55.3 | 15.2 | 44.6 | 81.7 | 53.7 |

| Intermediate (10–20% 10-year risk) | 6.8 | 15.0 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 13.7 |

| High (>20% 10-year risk) | 35.2 | 54.6 | 49.5 | 12.2 | 32.6 |

| Unknown/missing | 2.7 | 15.2 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 0.0 |

| Metabolic syndrome | |||||

| Present | 38.6 | 42.4 | 42.4 | 29.8 | 42.1 |

| Absent | 61.4 | 57.6 | 57.6 | 70.2 | 57.9 |

| FBS ≥100 mg/dL | |||||

| Present | 26.2 | 33.3 | 34.8 | 14.5 | 23.2 |

| Absent | 53.1 | 48.5 | 62.0 | 25.2 | 75.8 |

| Unknown/missing | 20.8 | 18.2 | 3.3 | 60.3 | 1.1 |

| Waist size >35 inches | |||||

| Present | 56.0 | 27.3 | 64.1 | 45.0 | 65.3 |

| Absent | 33.4 | 3.0 | 29.4 | 53.4 | 24.2 |

| Unknown/missing | 10.6 | 69.7 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 10.5 |

| HDL-Col <50 mg/dL | |||||

| Present | 35.9 | 36.4 | 33.7 | 23.7 | 56.8 |

| Absent | 62.5 | 60.6 | 65.2 | 74.8 | 41.1 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.6 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| Triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL | |||||

| Present | 25.1 | 27.2 | 29.9 | 21.4 | 20.0 |

| Absent | 72.0 | 60.6 | 69.0 | 74.8 | 77.9 |

| Unknown/missing | 2.9 | 12.1 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 2.1 |

| Blood pressure ≥130/≥ 85 mm Hg | |||||

| Present | 48.5 | 60.6 | 53.3 | 45.8 | 39.0 |

| Absent | 49.9 | 39.4 | 44.0 | 54.2 | 49.0 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.6 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 2.1 |

| Obesity | |||||

| BMI kg/m2 (mean) | 30.9 | 36.8 | 29.1 | 30.2 | 33.4 |

| Present | 46.3 | 63.6 | 35.9 | 44.3 | 63.2 |

| Absent | 48.3 | 21.2 | 56.0 | 55.7 | 32.6 |

| Unknown/missing | 5.4 | 15.2 | 8.2 | 0.0 | 4.2 |

BMI, body mass index; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

The frequency of MS was greater in Hispanics compared to NHW (57.0% vs. 31.6% p<0.0001) but not NHB (39.8%). Among Hispanics, the frequency of components of the MS, including abnormal waist circumference, low HDL-C, elevated TG, and fasting glucose, were greater than for NHW (all p<0.001).

Education, residence, and insurance in relation to MS

Education was significantly related to the MS and greater frequencies of MS occurred in those with education ≤high school (70.0%) compared to those with postgraduate education (26.7%, p<0.0001). Education was also related to components of the MS, including waist size, low HDL-C, elevated TG, and fasting glucose (all p<0.001). Frequency of the MS was increased in Medicaid participants compared to those with commercial insurance (57.8% vs. 24.7%, p<0.0001) and also in those from urban areas compared to suburban areas (43.3% vs. 22.5%, p=0.001). Using multivariate logistic regression, only an education lower than high school was related to an increased frequency of MS (OR 5.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2-12.4, p=0.0002).

Framingham Risk Score

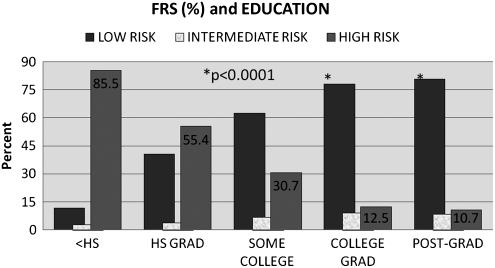

FRS was determined in 431 (97.3%) women classified for the presence or absence of the MS who had no history of CVD. Risk levels were high in 36.2%, intermediate in 6.9%, and low in 56.8%. Predicted risk for cardiovascular events was significantly related to race/ethnicity and education. The frequency of high FRS was greater in both Hispanics (78.6%) and NHB (47.7%) compared to NHW (14.2%) (both p<0.0001). Study participants with high school or less education had greater frequency of high FRS (85.5%) compared to those with postgraduate education (10.7%, p<0.0001). The frequency of high FRS was increased in high school graduates (55.4%) and in those with some college (30.7%) (both p<0.0001) but not in college graduates (12.5%) (Fig. 1). These effects remained significant in the multivariable logistic regression analysis, with the exception that NHB FRS no longer significantly differed from that of NHW.

FIG. 1.

Framingham Risk Score (FRS) and Education. The relation between high FRS (%) and years of education is shown. Study participants with some high school education or less had greater frequency of high FRS (85.5%) compared to those with postgraduate education (10.7%, p<0.0001).

Knowledge of CVD

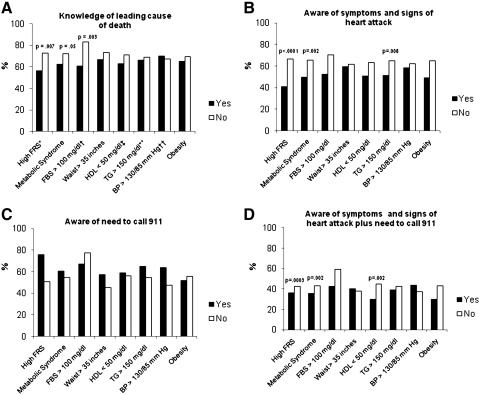

That the leading cause of death among women is heart disease was answered correctly by 68.9% (199 of 289), 59.9% (173 of 289) knew the symptoms and signs of a heart attack, and 56.5% (125 of 289) knew of the need to call 911. Additionally, 40.5% (117 of 289) knew the composite of symptoms and signs of a heart attack plus the need to call 911. The responses to the questions stratified by the presence or absence of high FRS, the MS, and individual risk factors are shown in Figure 2. Fewer study participants with high FRS or with the MS knew the leading cause of death. Moreover, fewer participants with high FRS or with the MS knew the symptoms and signs of a heart attack or the composite of the questions concerning symptoms and signs of a heart attack plus the need to call 911. However, in a multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusting for the effect of race/ethnicity, the MS was significantly associated only with a lack of knowledge of the composite of knowing the symptoms of a heart attack plus the need to call 911 (OR 0.425, 95% CI 0.181-0.997, p=0.049). High FRS was not associated with either knowledge of the leading cause of death or the composite of knowing the symptoms of a heart attack plus the need to call 911.

FIG. 2.

The responses to questions stratified by the presence or absence of high FRS, the metabolic syndrome (MS), and individual risk factors. Fewer study participants with high FRS or with the MS knew the leading cause of death. Moreover, fewer participants with high FRS or with the MS knew the symptoms and signs of a heart attack or the composite of the questions concerning symptoms and signs of a heart attack plus the need to call 911. BP, blood pressure; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; TG, triglycerides.

Discussion

Knowledge and awareness

The current study sought to document the extent of CVD knowledge and awareness among women with cardiometabolic risks and if such women are aware of options for managing an acute cardiac emergency. In a 2006 report,23 it was observed that national efforts to increase knowledge about the leading cause of death among women nearly doubled since 1997 (55% vs. 30%) and was significantly greater for white compared with black and Hispanic women (62% vs. 38% and 34%).23 A more recent 2010 observation, however, reported no significant overall change in knowledge of the leading cause of death since 2006.24 Moreover, although overall knowledge of the leading cause of death improved among white women,25,26 low knowledge rates among racial and ethnic minorities24 about the leading cause of death among women pose continuing challenges.27 Although the gap has narrowed since 1997, African American and Hispanic women remain significantly less aware than white women about the leading cause of death (blacks improved from 15% to 43% and Hispanics from 20% to 44%).

Our focus on study participants with the MS was related to the concern that high-risk women should be knowledgeable about CVD and aware of how to manage a cardiac emergency to reduce the potential for cardiac morbidity and mortality. Overall, the study participants had similar rates of knowledge about the leading cause of death compared to the national data.23,24,26 However, when stratified, fewer study participants with the MS knew the leading cause of death or the symptoms and signs of a heart attack (Fig. 2). Awareness about managing an emergency among study participants with the MS was also reduced, as was the composite of the questions concerning symptoms of a heart attack plus the need to call 911. Culturally competent health education materials made available through the resources provided by academic institutions, government, industry, and community-based educational interventions facilitate information about the implications of CVD.15,28,29 Providing repeated and sustained information about heart disease, the symptoms and signs of a heart attack, and the importance of calling 911 is critical to diminish the burden of morbidity and mortality for all women and particularly for high-risk women, such as those with cardiometabolic risk.24 Of note, however, is the flaw of assuming that factual knowledge directly changes behavior. For example, one report describes that increased awareness of CVD is associated with increased action to lower the risk of CVD,23 but another found that although knowledge of heart attack symptoms improved, the time to arrival in an acute care setting did not.25 We found that fewer study participants with the MS answered correctly when questions required not only factual knowledge, such as the symptoms and signs of a heart attack, but also an action implementation, such as the need to call 911. A worthy goal is to bridge the gap between collecting factual data and successfully incorporating such information into health options leading to appropriate decisions and conclusions.

Risk, race-ethnicity, and education

The MS occurred with greater frequency among study participants who are Hispanic and those with ≤high school education (both p<0.0001). Risk stratification also indicated that high FRS was significantly related to race/ethnicity and was greater in Hispanic and NHB participants (both p<0.0001) as well as those with ≤high school education (p<0.0001). In epidemiologic studies, education is a reliable indicator of social position and often is seen as the easier way of measuring present SES because it precedes other indicators, such as income or occupation-based social position, does not usually change during adulthood, and shapes health behaviors through attitudes, values, and knowledge.30 Individuals with limited education are presumed to be at higher risk for the MS because they have fewer psychosocial resources to manage stressful environments, accounting for a higher risk profile relative to those with more education.31–33 Analogous observations regarding education have been reported among far-removed MS populations, including Swedish women,34 Mexican American women living on the California-Mexico border,35 Portuguese women,36 and Canadian women.37 An ongoing concern is that women with the MS maintain lifelong patterns of diet and inactivity, thereby fostering the MS for themselves as well as for family members.38,39 This is troubling for young persons living in such households, who have a lifetime in which the consequences of risk can be played out and have a longer time in which combined risk factors for the MS can increase.40

MS and waist circumference

Waist circumference as a proxy measure of abdominal obesity is proposed to be a better anthropometric predictor of metabolic risk than BMI.41 We found the most frequent criterion among women with the MS was waist circumference ≥35 inches (56%). Moreover, we found that TG determinations were significantly higher (p<0.0001) and were found more frequently in study participants with waist circumference ≥35 inches (p<0.0001). The so-called hypertriglyceridemic waist, that is, plasma TG along with increased waist circumference, is considered to quantify the health hazards of visceral obesity better than waist alone and to represent dysfunctional, and highly lipolytic adipose tissue that is a major culprit behind cardiometabolic risk.42,43 The hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype is associated with the highest risk for fatal cardiovascular events and has been suggested to be a key indicator of CVD risk in postmenopausal women.44 As women with two easily identifiable features of the MS are at increased risk for accelerated atherosclerosis and adverse outcomes, targeting them for participation in rigorous educational efforts may lead to increased benefits.45

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional design and, like other cross-sectional studies, presents information in a single time frame, in this case, the baseline data associated with participants who are women. Additionally, although diverse women from a wide geographic range participated, most were from urban areas. Women from rural settings were less likely to be enrolled because of geographic distance from study sites and established referral patterns; thus, it is not clear if the findings have the same relevance for rural women. Further, the study did not have a randomized controlled group, and personal recall may limit the findings associated with self-reported questionnaires.

Conclusions

Study participants with the MS are less knowledgeable about (1) the leading cause of death and (2) the symptoms and signs of a heart attack and (3) less aware of the ideal option for managing a CVD emergency, that is, calling 911. Efforts to improve factual knowledge and enhance awareness are noteworthy goals for reducing CVD morbidity and mortality. Additionally, targeting individuals, such as women with cardiometabolic risk factors, in whom knowledge and awareness is less may further reduce adverse CVD outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Competitive Co-operative Agreement in FY2005 (OWH-05-031A) entitled, Improving, Enhancing and Evaluating Outcomes of Comprehensive Heart Health Care Programs for High-Risk Women, from the Department of Health and Human Services' Office on Women's Health. Grant numbers: Christ Community Health Services, Inc., HHCWH060006; Columbia University, HHCWH050003; Yale-New Haven Hospital, HHCWH050002; University of California, Davis Campus, HHCWH050005.

The project described was supported by grant UL1 RR024156 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kurian AK. Cardarelli KM. Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:143–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearcy JN. Keppel KG. A summary measure of health disparity. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:273–280. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mensah GA. Mokdad AH. Ford ES. Greenlund KJ. Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkman LF. Tracking social and biological experiences: The social etiology of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2005;111:3022–3024. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.509810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isomaa B. Almgren P. Tuomi T, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–689. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakka HM. Laaksonen DE. Lakka TA, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002;288:2709–2716. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Q. Wang Y. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: Do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yala SM. Fleck EM. Sciacca R. Castro D. Joseph Z. Giardina EG. Metabolic syndrome and the burden of cardiovascular disease in Caribbean Hispanic women living in northern Manhattan: A red flag for education. Metab Syndr Related Disord. 2009;7:315–322. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart KJ. Bacher AC. Turner K, et al. Exercise and risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome in older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuomilehto J. Lindstrom J. Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veazie MA. Galloway JM. Matson-Koffman D, et al. Taking the initiative: Implementing the American Heart Association Guide for Improving Cardiovascular Health at the Community Level: Healthy People 2010 Heart Disease and Stroke Partnership Community Guideline Implementation and Best Practices Workgroup. Circulation. 2005;112:2538–2554. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGruder HE. Greenlund KJ. Malarcher AM. Antoine TL. Croft JB. Zheng ZJ. Racial and ethnic disparities associated with knowledge of symptoms of heart attack and use of 911: National Health Interview Survey, 2001. Ethn Dis. 2008;18:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosca L. Banka CL. Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foody JM. Villablanca AC. Giardina EG, et al. The Office on Women's Health initiative to improve women's heart health: Program description, site characteristics, and lessons learned. J Womens Health. 2010;19:507–516. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villablanca AC. Beckett LA. Li Y, et al. Outcomes of comprehensive heart care programs in high-risk women. J Womens Health. 2010;19:1313–1325. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey questionnaire. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Office of Management and Budget. Race and ethnic standards for federal statistics and administrative reporting. Fed Register. 43(87):19269. (directive No. 15). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lloyd-Jones DM. Wilson PW. Larson MG, et al. Framingham Risk Score and prediction of lifetime risk for coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grundy SM. Balady GJ. Criqui MH, et al. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: Guidance from Framingham: A statement for healthcare professionals from the AHA Task Force on Risk Reduction. American Heart Association. Circulation. 1998;97:1876–1887. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection Evaluation, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keppel KG. Pearcy JN. Healthy people 2000: An assessment based on the health status indicators for the United States and each state. Healthy People 2000 Stat Notes. 2000:1–31. doi: 10.1037/e583782012-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosca L. Mochari H. Christian A, et al. National study of women's awareness, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2006;113:525–534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosca L. Mochari-Greenberger H. Dolor RJ. Newby LK. Robb KJ. Twelve-year follow-up of American women's awareness of cardiovascular disease risk and barriers to heart health. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:120–127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.915538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goff DC Jr. Mitchell P. Finnegan J, et al. Knowledge of heart attack symptoms in 20 US communities. Results from the Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment Community Trial. Prev Med. 2004;38:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christian AH. Rosamond W. White AR. Mosca L. Nine-year trends and racial and ethnic disparities in women's awareness of heart disease and stroke: An American Heart Association national study. J Womens Health. 2007;16:68–81. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenger NK. The female heart is vulnerable to cardiovascular disease: Emerging prevention evidence for women must inform emerging prevention strategies for women. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:118–119. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.942664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson JA. Kannel WB. Lopez-Candales A, et al. Avoiding the looming Latino/Hispanic cardiovascular health crisis: A call to action. J Cardiometabol Syndr. 2007;2:238–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.07534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson JA. Moreno PR. Badimon JJ, et al. Cardiovascular disease prevention and care in Latino and Hispanic subjects. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:77–85. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieger N. Williams DR. Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: Concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worsley A. Blasche R. Ball K. Crawford D. Income differences in food consumption in the 1995 Australian National Nutrition Survey. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1198–1211. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg L. Palmer JR. Wise LA. Horton NJ. Kumanyika SK. Adams-Campbell LL. A prospective study of the effect of childbearing on weight gain in African-American women. Obes Res. 2003;11:1526–1535. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunderson EP. Quesenberry CP., Jr Lewis CE, et al. Development of overweight associated with childbearing depends on smoking habit: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Obes Res. 2004;12:2041–2053. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wamala SP. Lynch J. Horsten M. Mittleman MA. Schenck-Gustafsson K. Orth-Gomer K. Education and the metabolic syndrome in women. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1999–2003. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.12.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallo LC. de los Monteros KE. Ferent V. Urbina J. Talavera G. Education, psychosocial resources, and metabolic syndrome variables in Latinas. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34:14–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02879917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos AC. Severo M. Barros H. Incidence and risk factors for the metabolic syndrome in an urban South European population. Prev Med. 2010;50:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choiniere R. Lafontaine P. Edwards AC. Distribution of cardiovascular disease risk factors by socioeconomic status among Canadian adults. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;162(Suppl):S13–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gliksman MD. Kawachi I. Hunter D, et al. Childhood socioeconomic status and risk of cardiovascular disease in middle aged U.S. women: A prospective study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:10–15. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sussner KM. Lindsay AC. Peterson KE. The influence of maternal acculturation on child body mass index at age 24 months. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis CE. Jacobs DR., Jr McCreath H, et al. Weight gain continues in the 1990s: 10-year trends in weight and overweight from the CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:1172–1181. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park YW. Zhu S. Palaniappan L. Heshka S. Carnethon MR. Heymsfield SB. The metabolic syndrome: Prevalence and associated risk factor findings in the US population from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:427–436. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Despres JP. Lemieux I. Bergeron J, et al. Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome: Contribution to global cardiometabolic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1039–1049. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Despres JP. Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanko LB. Bagger YZ. Qin G. Alexandersen P. Larsen PJ. Christiansen C. Enlarged waist combined with elevated triglycerides is a strong predictor of accelerated atherogenesis and related cardiovascular mortality in postmenopausal women. Circulation. 2005;111:1883–1890. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161801.65408.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahn HS. Valdez R. Metabolic risks identified by the combination of enlarged waist and elevated triacylglycerol concentration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:928–934. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]