Abstract

Religious institutions, which contribute to understanding of and mobilization in response to illness, play a major role in structuring social, political, and cultural responses to HIV and AIDS. We used institutional ethnography to explore how religious traditions—Catholic, Evangelical, and Afro-Brazilian—in Brazil have influenced HIV prevention, treatment, and care at the local and national levels over time.

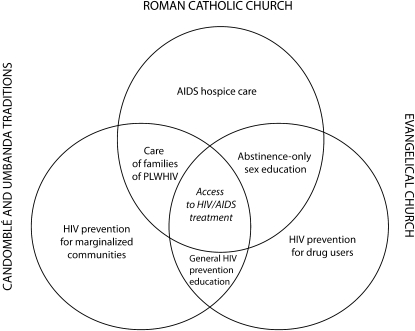

We present a typology of Brazil's division of labor and uncover overlapping foci grounded in religious ideology and tradition: care of people living with HIV among Catholics and Afro-Brazilians, abstinence education among Catholics and Evangelicals, prevention within marginalized communities among Evangelicals and Afro-Brazilians, and access to treatment among all traditions.

We conclude that institutional ethnography, which allows for multilevel and interlevel analysis, is a useful methodology.

IN SOCIETIES AROUND THE world, religious belief systems contribute to the interpretation and production of social norms surrounding new illnesses. Since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, religious organizations have played a central role in responding to HIV and AIDS.1,2 The relatively limited research that has addressed religion, HIV, and AIDS together, however, has tended to focus on the role of belief and spirituality in coping with HIV infection and bereavement and, to a lesser extent, on the role of religious values in shaping AIDS education programs.3–10 Little attention has been paid to the role religious institutions play in structuring broader social, political, and cultural responses to the disease.

FROM FAITH-BASED ORGANIZATIONS TO INSTITUTIONS

For the past decade, HIV and AIDS research has been shifting its focus away from individuals and toward communities, institutions, and systems of meaning and power.11–22 Research on religion and HIV has not caught up with this trend, as it has tended to compartmentalize—focusing on individuals and individual organizations in isolation from the larger institutions and structures of which they are parts.

Research on faith-based organizations has yielded useful information on local responses to HIV and AIDS.23,24 It has been unable, however, to capture the context of such organizations’ involvement. Research centered exclusively on faith-based organizations is limited in its ability to account for potential networks among social actors, tensions among such actors, disparities between different institutions as well as between different actors within institutions, and the overall context in which responses to HIV and AIDS occur.25 With the limitations of this faith-based approach in mind, we used institutional ethnography to study religious responses to HIV and AIDS in Brazil.

By conceptualizing three religious traditions as institutions, we were able to document how they have influenced HIV prevention, treatment, and care on the local, regional, and national levels. Our findings suggest that religious responses are not monolithic and that institutional ethnography may be the most effective way for public health researchers to explore the influence of religion on national responses to the AIDS epidemic.

BRAZIL AS A CASE STUDY

Brazil's National AIDS Program (NAP) is recognized as one of the leading HIV prevention and control programs in the world, and its treatment access program has been a model for other developing countries.26–30 Since its universal access program was implemented in 1996, Brazil has been a major player in the global AIDS policy arena and a leader in the fight to consider access to HIV medication a human right.31 The NAP's emphasis on rights and solidarity with vulnerable populations28,30 along with its commitment to working with a broad range of civil society groups, including religious organizations,2 makes Brazil ideal for the examination of religious institutions’ responses to HIV and AIDS.

Brazil's uniquely diverse array of religious institutions, traditions, and vocabularies also makes it particularly suitable for this examination.32–40 Brazil is nominally the world's largest Catholic country,41 and, in recent years, has given rise to one of the strongest Evangelical Protestant movements in the world. Brazil's myriad loosely related Afro-Brazilian religious sects (Candomblé, Umbanda, Xangô, etc.) also make it home to one of the largest syncretic religious traditions in the world.

INSTITUTIONAL ETHNOGRAPHY

The complexity of religious responses to HIV and AIDS in Brazil made the use of individual-level data insufficient and institutional ethnography particularly appropriate. Institutional ethnography is an inductive method of inquiry that begins by looking at the specific experiences, behaviors, and practices of individuals and then works outward to draw conclusions about the codes, systems, and structures by which they are governed.42 This “dual focus,” Quinlan notes in his study of institutional ethnography of multi-disciplinary primary health care teams, is part of what distinguishes it from other types of ethnography.42 Our institutional ethnographic methodology enables us to examine large social phenomena from the perspective of multiple social actors and social institutions. In our study, the social phenomena of interest were religious and governmental responses to the AIDS epidemic. The social institutions were religious traditions, at both the community organizational level (parish, church, and temple) and the national organizational level, and the government's NAP. The social actors included local and national religious leaders, community and national activists involved with religious communities, lay members of religious communities, and government officials. The inductive methodological strategy allowed us to examine responses on two main levels: the local level (illuminated through observed community responses and interviews with local activists and leaders) and the national level (illuminated through interviews with national leaders of religious institutions and the NAP, as well as through archival research).43

OUR APPROACH

We conducted our study across five Brazilian cities—Brasília, Porto Alegre, Recife, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo—over the course of five years. Our institutional ethnography consisted of three data collection methods: participant observation, qualitative interviews, and archival research. We have described each data collection method and their contributions to our analytical institutional ethnographic case studies. These methods were all used over the course of the study and continuously informed one another.

Participant Observation

Our institutional ethnography began with mapping the locations and conducting systematic participant observation44 of local religious institutions that have received funding from the government or the private sector to provide HIV and AIDS services. After identifying this initial group of institutions, we identified other key religious institutions in the same and neighboring communities. Participant observation involved close examination of organizational dynamics by using extended ethnographic field observation at these selected institutions. Ethnographers at each research site were trained to pay particular attention to different roles and valences of women and men in an organization, the heterogeneity versus homogeneity of group membership, and the extent to which the religious groups were connected to other religious, state, national, activist, or social service efforts. Ethnographers attended religious seminars and ceremonies to observe whether and how dialogue about HIV and AIDS was incorporated into interventions of faith-based programs across the sites. Participant observations were recorded in field notes. Our participant observations provided the initial entry into local religious responses to the HIV epidemic. To obtain primary data on institutional responses, we conducted a series of qualitative interviews.

Qualitative Interviews and Recruitment

We conducted qualitative interviews44 with a total of 245 people: 73 Catholics, 66 Evangelicals, 60 Afro-Brazilian religious followers, and 46 activists and government officials.

Through our mapping of the different religious institutions and our participant observation at each research site, we identified local religious leaders for qualitative interviews. We first identified a group of 30 key informants that consisted of 15 religious leaders, 10 lay leaders, and 5 local government officials involved with HIV/AIDS programming at faith-based nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). These leaders and officials were invited to participate in a series of key informant interviews. Key informant interviews provided us with unique local expertise and insights into our observations.45 Key informants also served as gate-keepers (i.e., individuals who provided access to local networks of individuals involved in religious institutional responses to HIV and AIDS). We recruited the second wave of interview participants through referrals from the initial wave of key informants. With this second wave, we conducted oral history interviews, in-depth interviews, and life-history interviews. Key informants also participated in the second wave of interviews. Oral history interviews focused on religious leaders’ memories and experiences of how their religious institutions had responded to HIV and AIDS since the beginning of the epidemic. Oral history respondents were each interviewed two or three times.

Whereas the oral histories focused on past responses, the in-depth interviews focused on present institutional responses and efforts to address the epidemic. In-depth interviews were conducted with religious and lay leaders, youth and adult members of religious traditions, and former and current NAP government officials. We conducted 200 in-depth interviews that focused on religious belief systems as they relate to HIV and AIDS, organizational structure and the internal organization of ecclesiastical power, relations with external (local and national) dialogues on HIV and AIDS policy, areas of current interventions, and gaps in current interventions. The NAP officials, who were selected because of their extensive experience working in partnership with religious institutions, were asked a set of questions that covered demographic data (e.g., age, gender, occupation, schooling, religion); views on drug use, abortion, homosexuality, and teenage pregnancy; responses to AIDS (personal role in government, perceptions of civil society organizations’ responses to the epidemic, and personal involvement in religious responses to the epidemic); and how the NAP has worked with religious organizations (type of work, financial relationships, and other interactions on a national and international level).

Finally, in-depth interview participants were invited to participate in life-history interviews to narrate their experiences negotiating sexual and nonsexual HIV risks and their religiosity, how the impact of religious social policy on HIV prevention and treatment has affected them personally, and their involvement (or lack thereof) in local, regional, and national HIV and AIDS movements. We conducted 30 such interviews across the sites.

Archival Research

We conducted archival research through an analysis of academic journal articles, mass media articles, organizational and institutional reports and newsletters, NAP documents, and other governmental documents to assess changes in the ways religious organizations have addressed HIV and AIDS–related issues over time (historical variations) and space (geographical and regional differences). Archival research was especially useful in identifying key informants with historical knowledge of national-level religious responses to AIDS and, later, in drawing connections between our on-the-ground data (from participant observation and observations) and broader historical and contextual themes. All archival data were cataloged and stored at the Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association by a trained archivist. The research team compiled a bibliography of 475 references and a 75-page annotated bibliography that included books, pamphlets, bulletins, academic journal articles, and other articles acquired at ethnographic site visits and conferences.

Building Analytical Case Studies

To analyze institutional responses to the AIDS epidemic, the research teams at each of the study sites coded all of the materials and held a series of research meetings to build analytical case studies that explored responses to the epidemic. We built one case study per religious tradition in each site except for Brasília, resulting in 12 tradition-specific case studies. (The decision not to conduct tradition-specific case studies in Brasília was made collectively by the research teams across all the sites.) Some of our case studies focused on individual organizations. For example, we selected an Evangelical NGO to represent the local Evangelical response to the AIDS epidemic in Rio de Janeiro. The case study report analyzed the NGO's historic and current responses, the nuances of its organizational structure, and the discrepancies that exist within that structure (e.g., between the members and the executive coordinator). A second type of case study looked at organizations, movements, and initiatives that provided interinstitutional spaces for the examination of religious responses to HIV. We completed nine case studies of this type. Two examples are (1) the AIDS Pastoral, an arm of the Catholic Church that has strong community roots and receives funding and technical support from the NAP (this case study was built with data from Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre), and (2) a national case study on the NAP in relation to religious institutions from all three traditions (built with data from Brasília, the capital of Brazil), focusing on the way in which NAP's institutional structure and longstanding commitment to solidarity and citizenship have helped shape its positive partnerships with religious institutions.

These case studies were written as reports in Portuguese. Independently, three researchers examined the 21 case studies (12 tradition-specific case studies plus nine interinstitutional case studies) to explore how the three religious traditions in Brazil have influenced HIV prevention, treatment, and care on a local and national level. We dedicated three meetings with the 17 members of the research team to discussing the preliminary findings for the analysis presented in this article. We first examined the materials generated from the participant observations and interviews with local leaders and activists to determine which areas of HIV prevention and treatment have been addressed and which areas have received minimal or no attention within a particular religious tradition.

After examining local responses, we moved on to examine state and national responses with data from interviews with NAP officials and activists, as well as archival research. We first identified foci that were unique to specific religious traditions and then identified and examined areas of overlap. Findings from the archival research allowed us to link public statements made by official religious bodies to the primary data collected through observations and interviews. We discussed discrepancies and disagreements until we arrived at a consensus on a foundational typology (i.e., the types of services and areas of interventions) of the three religious traditions. The data and typology were reviewed by an independent Brazilian scholar of religion and AIDS, who provided feedback and modifications to our analysis. Finally, we are able to present a general typology of the AIDS division of labor—that is, the ways in which tasks related to HIV policy advocacy, prevention, and treatment services have been distributed, divided, and organized across religious traditions at the local and national levels.

HISTORICAL INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSES TO AIDS

Institutional ethnography allowed us to explore religious institutions’ historical and current responses to HIV and AIDS. Brazilian religious institutions’ traditions, denominations, and archdioceses are far from homogenous or static. They comprise a number of diverse positions and have exhibited gradual change over time.

We present an overview of these major institutional roles. We begin by describing the ways in which each religious tradition became involved with the AIDS epidemic, as these routes of entry have structured institutional responses to HIV and AIDS throughout the years. We then explore the shift in the typological division of labor that occurred after the development of antiretroviral therapy (ART). Despite initially problematic responses, since the early 1990s, religious institutions have played a major role in responding to communities’ HIV- and AIDS-related needs. We focus on constructive responses in this article as a means of exploring how and why three divergent religious traditions have made positive contributions to national- and community-level responses to the epidemic despite their continuing stigmatization of HIV and people living with HIV and their moral preoccupations with many of the behaviors through which HIV is transmitted. Figure 1 depicts the constructive roles that these three traditions have played in responding to the AIDS epidemic. These divisions do not demarcate mutually exclusive domains; rather, they represent the traditional gravitations of each religious institution.

FIGURE 1.

Typology of AIDS religious division of labor in Brazil, 1989–2009.

Note. PLWHIV = people living with HIV.

From the 12 tradition-specific case studies, we explored major roles that each tradition has played in responding to the AIDS epidemic: the Roman Catholic Church's focus on clinical and hospice care, the Evangelical focus on the elimination of drug addiction, and two Afro-Brazilian traditions’ (Candomblé and Umbanda) mobilization around HIV prevention, especially in relation to sexual risk.

AIDS Clinical and Hospice Care (Roman Catholic Church)

At the onset of the AIDS epidemic, a number of leading Catholic officials spoke out against the supposedly immoral behaviors associated with HIV transmission, such as homosexual relations and heterosexual promiscuity. These initial Catholic responses contributed to the early, widespread stigmatization of AIDS.41

By the late 1980s, however, the official Catholic Church shifted away from moral judgment and toward the applicability of its longstanding commitment to addressing the needs of the suffering. The Church developed hospices, medical clinics, and home care programs for female and travesti (transvestite) prostitutes, indigent persons, and other individuals with AIDS.2,41 For more than a decade now, the National Council of Bishops has issued statements noting the Church's commitment to solidarity with persons living with HIV and describe how pastoral work with persons living with HIV fits in with the “Samaritan spirit of Christianity.”41,46 This emphasis on solidarity has been institutionalized through AIDS Pastoral, a social action service that grew out of the Church's earlier experience with a National Health Pastoral and a Children's Pastoral that were officially created by the National Council of Bishops in 1999. AIDS Pastoral coordinates and articulates Catholic responses to the epidemic nationally, regionally, and locally.

HIV Prevention and Education (Afro-Brazilian Traditions)

Many Afro-Brazilian religious leaders also distanced themselves from HIV and AIDS in the early years of the epidemic.41 Afro-Brazilian religions already had a history of being stigmatized in society before the onset of the epidemic. Widespread associations between these religious traditions and people, such as men who have sex with men, who were initially described as being at high risk for HIV infection, along with public health officials’ consideration of Afro-Brazilian religious practices, such as ritual scarification, as potential routes of HIV transmission,41,47 exacerbated religious leaders’ concerns about being further stigmatized in the context of the AIDS epidemic.41,48

Despite their initial distancing, a number of Afro-Brazilian religious leaders became involved with HIV education and early treatment relatively quickly.41 Particularly early in the epidemic, before the introduction of ART, many people with HIV-related health problems looked to Afro-Brazilian religious traditions for the type of healing they had traditionally provided in response to illness perceived to be untreatable by modern Western medicine.41 After the emergence of ART, Afro-Brazilian religious groups expanded their focus to include HIV education and prevention.41 AIDS NGOs and governmental agencies reached out to Afro-Brazilian religious leaders for help with reaching Brazil's Black communities.41

Drug Rehabilitation and Addiction Treatment (Evangelical Churches)

The Brazilian cocaine epidemic peaked during the 1990s, and a crack cocaine epidemic has reemerged over the past five years. The cocaine epidemic has mostly affected poor urban communities, where Evangelical churches have a disproportionate presence.49 Thus, the cocaine epidemic has been a central issue for Evangelical churches. Because of the overwhelming presence of drug addiction and drug-related violence and the widespread belief that social and moral decay are destroying poorer communities in Brazil, Evangelical groups,41 which value living free of “moral evils,” have been able to establish prominent drug detoxification and abstinence-based rehabilitation programs throughout the country. HIV education and prevention are central to these rehabilitation programs, which promote abstinence from injection drug use and needle sharing, abstinence from extramarital and premarital sexual intercourse, and abstinence from sexual intercourse under the influence of psychoactive drugs, as well as early HIV testing. As a consequence of its involvement in drug abuse treatment and its strong presence in areas where reproductive health issues such as teenage pregnancy are of concern, the Evangelical movement has been a major, often controversial, player in the national landscape of HIV prevention.

AREAS OF OVERLAP IN THE HIV AND AIDS RELIGIOUS LANDSCAPE

We noticed a trend of parallel action in religious institutions’ responses to HIV and AIDS. In three different areas, efforts were similar across denominations but rarely coordinated because of the lack of interdenominational dialogue. Roman Catholic and Candomblé traditions have both mobilized to support and create programs that assist not only persons living with HIV but also their families, relatives, and partners. Similarly, both Evangelicals and Roman Catholics have promoted and supported abstinence-only and marriage fidelity sexual education for youths. Evangelicals and the two Afro-Brazilian traditions (Candomblé and Umbanda) have focused on HIV prevention within marginalized communities. Evangelicals, Catholics, and both Afro-Brazilian traditions have all promoted awareness of HIV and AIDS as a social issue disproportionately affecting the Brazilian urban poor and have based their support for access to treatment and care upon this understanding.

ACCESS TO HIV TREATMENT

We documented how Roman Catholic, Evangelical, and Candomblé and Umbanda groups have mobilized to obtain universal access to HIV and AIDS treatment (which became the standard in Brazil in 1996).50 Despite their shared political landscape and use of community organizing to advocate treatment access, the three traditions have addressed access to treatment for somewhat different reasons. The Catholic Church views the amelioration of social suffering as central to its work and has therefore focused on how guaranteeing universal access to AIDS medications diminishes the physical and social suffering of HIV-positive individuals. The Evangelicals who have mobilized around access to treatment have done so as part of their mission to save lives. Their mobilization has also been influenced by their belief that all people are equal in the eyes of God and that the state should promote and respect equality by providing universal access to health care. Afro-Brazilian traditions have historically been engaged with issues of marginalization, playing central roles in mobilization on behalf of the rights of Black Brazilians. They have taken up the issue of access to HIV treatment as part of their larger commitment to advocacy for the rights of those affected by economic, racial, gender, sexual, and religious marginalization.

In addition to the direct health effects that universal access to treatment has had on HIV-positive individuals in Brazil, support for universal access has transcended religious divides. It has also had a major impact on reframing HIV infection as a chronic but manageable health condition, which has contributed to the destigmatization of the virus and has thus also opened doors for more widespread HIV prevention and education in Brazil, as well as for global HIV treatment scale-up. Brazil has increasingly become a major player in international HIV policy debates, using diverse global forums (e.g., the World Health Organization's World Health Assembly, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS] Program Coordinating Board, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria) to consistently introduce policy measures aimed at strengthening access to HIV treatment. At the core of Brazil's policy of universal access to HIV medication is the understanding that health is a human right that should be distributed equally, not according to race or income—an understanding that was clearly codified in Brazil's 1988 constitution, which included the right to health as one of the key rights of all Brazilian citizens. Although the specific values and ideologies that informed each religious tradition's support for universal access varied, all of the traditions were guided by the belief that all people should be healthy and that part of their religious tradition's duty is to improve all humans’ well-being. These religious institutions’ commitment to improving all people's well-being paralleled—and, in some cases, directly contributed to—the NAP's commitment to promoting access to treatment as a human right.51

SUMMARY

Our institutional ethnography proved to be a robust methodology across all of our research sites, as it allowed a nuanced exploration of responses to the AIDS epidemic. We were able to capture not only historical, contextual information and local, individual data but also information on how individuals and individual communities, churches, and organizations have responded to changing contexts and vice versa.

One of the primary purposes of this article was to encourage the use of institutional ethnography to study differences in religious responses to HIV and AIDS across locations and over time, but it should be noted that data collection methods were adapted in each location according to the disciplinary leanings of the different investigators, as well as the specific local circumstances. This methodology enabled us to generate more than 25 different nuanced analyses of relationships among individual social actors and broader social institutions.52–60 The methods we describe here provide an example of how institutional ethnography can successfully be used, but they should not be expected to be perfectly replicable in any other context.

The analysis presented here is the first overarching analysis of the landscape of religious institutional responses to HIV and AIDS in Brazil based on empirical longitudinal research conducted across multiple sites. The initial responses of all three of these religious traditions to the AIDS epidemic were highly problematic, as they were often guided by moral judgments and contributed to the stigmatization of HIV and persons living with HIV.41 Over time, however, a variety of more positive responses have developed,41 converging around access to treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Across the globe, religious institutions have been at the forefront of social responses to HIV and AIDS—a fact that has received increased attention in recent years because of a growing emphasis on the role of faith-based organizations in providing HIV-related services. Despite this recognition, we still know remarkably little about the complex roles that religious institutions have played in responding to the epidemic, and assessments of their contributions often rely more on stereotypes than on careful analysis of empirical research. This lack of knowledge has minimized our ability to effectively draw upon the most positive contributions of religious organizations (and protect against negative contributions) when designing and implementing programs and policies aimed at confronting the epidemic.

Institutional ethnography provides a framework for understanding the role that religious institutions have played (and might play in the future) in responding to the epidemic. A fuller understanding of the multidimensional role of religious responses to the epidemic requires us to move beyond the focus on individual-level data that frequently characterizes behavioral research on HIV and AIDS and to focus, as well, on multilevel social, cultural, and historical data. If our research in Brazil is any indication, we suspect that the findings that will result from such investigations will tell complex stories that move beyond a utilitarian focus on the role of faith-based organizations in implementing HIV and AIDS–related services and suggest the power of religious institutions in shaping the politics of the epidemic. This research will also illuminate opportunities for cross-denominational collaboration among religious organizations and for interventions within religious institutions.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on data collected from the research study Religious Responses to HIV/AIDS in Brazil, sponsored by the US Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant 1 R01 HD050118; principal Investigator, R. G. Parker).

This national study was conducted in four sites, at the following institutions and by their respective coordinators: Rio de Janeiro (Associaça˜o Brasileira Interdisciplinar de AIDS/ABIA—Veriano Terto Jr), Sa˜o Paulo (Universidade de Sa˜o Paulo/USP—Vera Paiva), Porto Alegre (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul/UFRGS—Fernando Seffner), and Recife (Universidade Federal de Pernambuco/UFPE—Luís Felipe Rios). Additional information about the project can be obtained via e-mail from religiao@abiaids.org.br or at http://www.abiaids.org.br, the Associaça˜o Brasileira Interdiciplinar de AIDS Web site.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.National Research Council Panel on monitoring the social impact of the AIDS epidemic, religion and religious groups. : Jonsen AR, Stryker J, The Social Impact of AIDS in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993:117–157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galva˜o J. As respostas religiosas frente à epidemia de HIV/AIDS no Brasil [Religious responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Brazil]. : Parker R, Políticas, Instituições e AIDS: Enfrentando a Epidemia no Brasil [Politics, Institutions and AIDS: Confronting the Epidemic in Brazil]. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Jorge Zahar/ABIA; 1997:109–134 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman CL. The contribution of religious and existential well-being to depression among African American heterosexuals with HIV infection. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2004;25(1):103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello CL. Religion and AIDS-related bereavement: a study of partners and family members. Dissertation Abstracts Int. 1993;54(6-B):3335 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford I, Allison KW, Robinson WL, Hughes D, Samaryk M. Attitudes of African-American Baptist ministers toward AIDS. J Community Psychol. 1992;20:304–308 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edelheit JA. The passion to heal: a theological pastoral approach to HIV/AIDS. Zygon. 2004;39:497–506 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menz RL. Aiding those with AIDS: a mission for the Church. J Psychol Christ. 1987;6(3):5–18 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woods TE, Ironson GH. Religion and spirituality in the face of illness: how cancer, cardiac, and HIV patients describe their spirituality/religiosity. J Health Psychol. 1999;4:393–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remle RC, Koenig HG. Religion and health in HIV/AIDS communities. : Plante TG, Sherman AC, Faith and Health: Psychological Perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001:195–212 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW. The perceived benefits of religious and spiritual coping among older adults living with HIV/AIDS. J Sci Study Relig. 2002;41(1):91–102 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann J, Tarantola D, Netter T. AIDS in the World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farmer P, Connors M, Simmons J, Women, Poverty and AIDS: Sex, Drugs and Structural Violence. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farmer P. Infections and Inequalities: The Modern Plagues. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker R. Sexuality, culture and power in HIV/AIDS research. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2001;30:163–179 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoepf B. International AIDS research in anthropology: taking a critical perspective on the crisis. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2001;30:335–361 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farmer P. Pathologies of power: rethinking health and human rights. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1486–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker R. Evolution in HIV/AIDS prevention, intervention and strategies. Int J Psychol. 2001;35:155–165 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Treichler P. How to Have Theory in an Epidemic: Cultural Chronicles of AIDS. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker R. Empowerment, community mobilization, and social change in the face of HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 1996;10(suppl 3):S27–S31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker R, Barbosa R, Aggleton P. Framing the sexual subject. : Parker R, Barbosa R, Aggleton P, Framing the Sexual Subject: The Politics of Gender, Sexuality and Power. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000:1–25 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso AM, Koreck MT. Silences: ‘Hispanics,’ AIDS and sexual practices. Differences. 1989;1:101–124 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolton R, Singer M, Rethinking AIDS Prevention: Cultural Approaches. Philadelphia, PA: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1030–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis SA, Liverpool J. A review of faith-based HIV prevention programs. J Relig Health. 2009;48:6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatters LM. Religion and health: public health research and practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:335–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health of Brazil The Brazilian Response to HIV/AIDS: Best Practices. Brasilia, Brazil: UNAIDS; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker R, Pasarelli CA, Terto V, Jr, Pimenta C, Berkman A, Muñoz-Laboy M. Introduction. Divulgaça˜o em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27(Special Issue):140–142 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berkman A, Garcia J, Muñoz-Laboy M, Paiva V, Parker R. Brazilian response to HIV/AIDS: lessons learned for controlling and mitigating the epidemic in developing countries. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1162–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg T. Look at Brazil. New York Times Magazine. January 28, 2001:26–35 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okie S. Fighting HIV—lessons from Brazil. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):1977–1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teixeira PR. Universal access to AIDS medicines: the Brazilian experience. Divulgaça˜o em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27(Special Issue):184–191 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bastide R. Brasil, Terra De Contrastes [Brazil, Land of Contrasts]. Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil: DIFEL Editorial; 1959 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bastide R. The African Religions of Brazil. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burdick J. Looking for God in Brazil. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chesnut RA. Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom and the Pathogens of Poverty. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berryman P. Religion in the Megacity: Catholic and Protestant Portraits From Latin America. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruneau TC. The Church in Brazil: The Politics of Religion. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guimara˜es MA. E um Umbigo, na˜o é? A Ma˜e Criadeira, um Estudo sobre o Processo de Construça˜o de Identidade em Comunidades de Terreiro [It's the Belly Button, Isn't It? Nonbiological Mothers, a Study About the Construction of Identity in Religious Communities; master's thesis]. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Pontificia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motta R. Religia˜o e Estratégias Adaptivas em Ambiente Urbano: Xangô do Recife [Religion and Adaptive Strategies in an Urban Setting: Xangô in Recife]. Recife, Pernambuco: Anais da XI Reunia˜o da Associaça˜o Brasileira de Antropologia; 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sodré M. O Terreiro e a Cidade: A Forma Social Negro-Brasileira [The Temple and the City: Afro-Brazilian Social Organization]. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker R. Building the foundations for the response to HIV/AIDS in Brazil: the development of HIV/AIDS policy, 1982–1996. Divulgaça˜o em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27:143–183 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quinlan E. The ‘actualities’ of knowledge work: an institutional ethnography of multi-disciplinary primary health care teams. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(5):625–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burawoy M. The Extended Case Method: Four Countries, Four Decades, Four Great Transformations, and One Theoretical Tradition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernard H. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schensul SL, Schensul JJ, LeCompte MD. Essential Ethnographic Methods: Observations, Interviews and Questionnaires. Walnut Creek, CA; London, England: Altamira Press; 1999:121–148 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Confereˆncia Nacional de Bispos do Brasil (CNBB) Diretrizes gerais da aça˜o pastoral da Igreja no Brasil: 1991-1994 [General guidelines for pastoral action of the church in Brazil]. Sao Paulo, Brazil: Paulinas; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiik FB. When the “buzios” say no! – the cultural construction of AIDS and its social disruptive nature: the case of Candomblé (Afro-Brazilian) religion. Oslo, Norway: University of Oslo, 1994. (mimeo) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fry P. Para Inglês Ver: Identidade e Política na Cultura Brasileira [Identity and Politics in Brazilian Culture]. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Jorge Zahar; 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Almeida R, Montero P. Trânsito religioso no Brasil [Religious customs in Brazil]. Sa˜o Paulo em Perspectiva. 2001;15:92–101 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ministério de Saúde, Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais AIDS Drug Policy – Ministry of Health/Brazil. Available at: http://www.aids.gov.br. Accessed January 29, 2010

- 51.Murray L, García J, Muñoz-Laboy M, Parker R. Strange bedfellows: the Catholic Church and Brazilian National AIDS Program in the response to AIDS in Brazil. Soc Sci Med. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seffner F, Silva CGM, Maksud I, et al. Respostas religiosas à AIDS no Brasil: impressões de pesquisa acerca da pastoral de DST/AIDS da Igreja Católica [Religious responses to AIDS in Brazil: impressions from research about the STD/AIDS Pastoral of the Catholic Church]. Ciencias Sociales y Religión/Ciências Sociais e Religia˜o. 2008;10(10):159–180 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seffner F, Silva CGM, Maksud I, et al. Respostas religiosas à AIDS no Brasil. [Religious responses to AIDS in Brazil]. Os Urbanitas. 2009;5:1–20 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rios LF, de Aquino FL, Muñoz-Laboy M, Oliveira C, Parker R. Católicos, fidelidade conjugal e AIDS: entre a cruz da doutrina moral e as espadas do cotidiano sexual dos adeptos. [Catholics, fidelity, and AIDS: between the cross of the moral doctrine and the swords of the sexual life of everyday followers]. Debates do NER. 2008;9(14):135–156 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rios LF, Parker R, Terto V., Jr Sobre as inclinações carnais: inflexões do pensamento crista˜osobre os desejos e as sensações prazerosas do baixo corporal [Carnal inclinations: variation in Christian thinking about desire and pleasurable sensations of the lower body]. PHYSIS. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rios LF, Aquino F, Coelho D, Oliveira C, Almeida V, Parker R. Masculorum concubitores: visões sobre a homossexualidade entre católicos do Recife [Masculine: visions of homosexuality among Catholics in Recife]. Vibrant. In press [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paiva V, Garcia J, Rios LF, Santos AO, Terto V, Jr, Muñoz-Laboy M. Religious communities and HIV prevention: an intervention-study using a human rights-based approach. Glob Public Health. 2010;7:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.García J, Muñoz-Laboy M, de Almeida V, Parker R. Local impacts of religious discourses on rights to express same-sex sexual desires in periurban Rio de Janeiro. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2009;6(3):44–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silva CG, Santos AO, Carli D, Paiva V. Religiosidade, juventude e sexualidade: entre a autonomia e a rigidez [Religiosity, youth and sexuality: between autonomy and rigidity]. Psicol Estud. 2008;14(3):683–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rios LF, Paiva V, Maksud I, et al. Os cuidados com a “carne” na socializaça˜o sexual dos jovens [The care of the “flesh” in the sexual socialization of youth]. Psicol Estud. 2008;14(3):673–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]