Abstract

We calculate the maximum type 1 error rate of the pre-planned conventional fixed sample size test for comparing the means of independent normal distributions (with common known variance) which can be yielded when sample size and allocation rate to the treatment arms can be modified in an interim analysis. Thereby it is assumed that the experimenter fully exploits knowledge of the unblinded interim estimates of the treatment effects in order to maximize the conditional type 1 error rate. The ”worst case” strategies require knowledge of the unknown common treatment effect under the null hypothesis. Although this is a rather hypothetical scenario it may be approached in practice when using a standard control treatment for which precise estimates are available from historical data. The maximum inflation of the type 1 error rate is substantially larger than derived by [1] for design modifications applying balanced samples before and after the interim analysis. Corresponding upper limits for the maximum type 1 error rate are calculated for a number of situations arising from practical considerations (e.g. restricting the maximum sample size, not allowing sample size decreases, allowing only increase of the sample size in the experimental treatment). The application is discussed for a motivating example.

Keywords: Sample size reassessment, changing allocation rates, interim analysis, maximum type 1 error rate, z-test, conditional error function

1. Introduction

Sample size reassessment in an adaptive interim analysis based on an interim estimate of the effect size can considerably increase the type 1 error rate if the pre-planned level α test is applied for the final analysis. For sample sizes balanced between treatments Proschan and Hunsberger [1] investigated the maximum type 1 error rate inflation of the one-sided test for the comparison of two normal means (variance known). They showed that the type 1 error rate may be inflated from 0.05 to 0.1146 if in an interim analysis the second stage sample size is chosen to maximize the conditional error function of the final one-sided z-test. Adaptive combination tests (see [2], [3], [4], [5]) and tests based on the conditional error function (see [1], [6], [7]) have been proposed which allow for such interim design modifications without inflating the type 1 error rate. For a short review of sample size re-estimation in clinical trials see e.g. [8].

The literature to date for the z-test has assumed that the allocation ratios between the control and the selected treatment groups are the same before and after the interim analysis. Under this assumption the conditional error function does not depend on the unknown nuisance parameter, the common mean under the null hypothesis. This paper investigates how much the type 1 error rate may be inflated if conventional tests are used when not only the sample size but also also the individual allocation ratios for the control and treatment group can be adapted in an interim analysis. In the following we investigate the impact on the maximum overall type 1 error rate by including this type of adaptation in flexible two-stage designs. This problem is important because the application of the conditional error principal to control the overall type 1 error rate is complicated when nuisance parameters are involved (for examples see [9], [10], [11]). Note that in the regulated environment of pharmaceutical drug development strict control of the type 1 error rate is one of the key issues (e.g. [12], [13]). We acknowledge, that in the current European guidance on adaptive designs for clinical trials the problem of treatment effect heterogeneity across stages is emphasized (see [13]). Changing the randomization ratio might lead to the recruitment of slightly different patient populations which in turn might lead to differences in the treatment effects. One way to deal with the problem is to explore the interaction between treatment and stage by appropriate test statistics (see e.g. [14]). However, in the following we will not account for such pre-test procedures in our methodology.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 starts with a motivating example. In Section 3 we calculate the maximum overall type 1 error rate for the two-sample z-test allowing full flexibility for the choice of the second stage sample sizes in the treatment and control group. In Section 4 we investigate the impact of adaptation constraints on the maximum overall type 1 error rate and present the applications to the motivating example. Section 5 considers a scenario with a historical control group. Section 6 follows with concluding remarks.

2 Motivating Example

Assume that a randomized clinical trial to compare an experimental and a standard treatment has been pre-planned with an interim analysis to be performed when the continuous primary outcome variable has become available for one half of the total pre-planned number of patients. A one-sided test for superiority of the experimental treatment at the level 0.025 is planned for the final statistical analysis. (We assume that the sample sizes are large enough so that the distributional assumption for the test statistics in this manuscript apply to a good approximation.) Restricted randomization is applied to ensure that sample sizes are balanced between treatments at both stages. The only purpose of the interim analysis is to take the opportunity of stopping for futility because of lack of evidence for a sufficient treatment difference, which is a scenario of increasing practical importance. Since such decisions generally account also for aspects other than efficacy, like patient safety and burden, no formal stopping rule for the primary outcome variable has been pre-defined. The plan excludes reducing the pre-planned total sample size if the study proceeds to the second stage because a certain amount of information on safety of the experimental treatment in comparison with the information on safety of the standard treatment is needed for a reasonably accurate assessment of the relationship of risk to benefit.

In the interim analysis concern arises if a signal of a possible unexpected adverse effect occurs in the experimental treatment group. The data safety monitoring board of the study strongly suggests an extension of the second stage sample size in order to collect more information on this emerging issue. Sufficient information on the safety profile of the standard treatment is available from the past so that increasing the sample size of the control group is not necessary. Moreover, financial resources limit the increase in sample size to no more than 50%.

At the interim analysis, it is decided to recruit up to a tripling of the planned sample size for the second stage for the experimental treatment but to leave the second stage sample size in the standard treatment group unchanged.

One of the reviewers pointed out another scenario that fits the paradigm of this paper: Response-adaptive randomization (see [15]) is based on two essential features, seeing ongoing results and changing probabilities accordingly which can change the allocation ratio substantially. Although response-adaptive randomization does this continually, the motivating example can be thought of as specific version of response-adaptive randomization where the adaptation does not occur until a substantial amount of data is available. As we will see in Section 3 below, some of the strategies of sample size reallocation to maximize the type 1 error rate would also result from a response-adaptive reasoning: e.g. if at interim a poor outcome has been observed in the control group patients should be further treated preferably with the superior treatment.

3 The maximum overall type 1 error rate for the two-sample z-test

We consider the comparison of the means of two normal distributions with common known variance σ2 (= 1 without loss of generality) in a one-sided test of the null hypothesis

where the index 0 indicates the control group. The assumption of known variance is frequently applied in practice to hold at least asymptotically when using consistent variance estimators. After observations in the control and observations in the treatment group an interim analysis is performed. In the following we use bracketed upper indices for denoting stages if necessary. In the interim look the experimenter may adapt the second stage sample sizes to in the treatment and in the control group with , . Then the conditional type 1 error rate can written as (see Appendix A.1):

| (1) |

where and have independent standard normal distributions, and are the the first stage sample means in the treatment and control group respectively. Here μ denotes the common true mean under the null hypothesis, Φ denotes the normal cumulative distribution function, z1−α the (1 − α)-quantile of the standard normal distribution and α the unadjusted nominal significance level to be applied in the final analysis. The notation in formula (1) indicates that all the test statistics in the following are defined as standardized differences of sample means to the true common mean μ under the global null hypothesis. Consequently, when calculating the maximum overall error rate we pretend that the experimenter has knowledge of the common mean μ, without loss of generality we assume μ = 0. Although this assumption may appear unrealistic in practice, consider a clinical trial comparing a new treatment with a standard treatment. This standard treatment has been applied in large sets of patients so that the expected effect size is known fairly accurately from historical data. This situation mimics the knowledge of the common unknown mean under the null hypothesis. Such an assumption that the effect of the control group is well established is made, e.g. when demonstrating superiority against a putative placebo by showing non-inferiority against an active control treatment (see e.g. [16]).

If r(1) = 1 and formula (1) reduces to the formula given by [1]. The maximum overall type 1 error rate achievable by sample size reassessment and reallocation is given by:

| (2) |

where . Here ϕ denotes the density function of the standard normal distribution. Let in the following , i = 0, 1 denote the optimal sample size inflation factors to yield the maximal conditional type 1 error rate for a given in the control and in the treatment group at the interim analysis, respectively.

The maximum overall type 1 error rates possible are equal for r(1) = r and . Calculations of the function show that its maximum occurs when r(1) = 1, see Figure 2 at the end of this section. For the behaviour of the function for r(1) → 0 or by symmetry r(1) → ∞ see Section 5. Therefore, in the following we focus on the overall worst case scenario r(1) = 1 (noting that this is also the one which will be most likely pre-planned in practice) and for simplicity in this case we skip r(1) = 1 in the notations. For r(1) = 1 it can easily be seen that the maximum conditional error function is symmetric around the line . At the end of the section we also indicate how the calculations change for r(1) ≠ 1.

Figure 2.

for different values of r(1). α was set to 0.01 (solid line), 0.025 (dashed line) and 0.05 (dotted line).

In the following we try to maximize the type 1 error rate allowing second stage sample sizes tending to 0 or to ∞. We are aware that these cases are of rather theoretical interest, however, it is our intention to show the most extreme inflation of the type 1 error rate. In the next section and also in the example we will consider constraints on the second stage sample sizes referring to potentially realistic situations in practice.

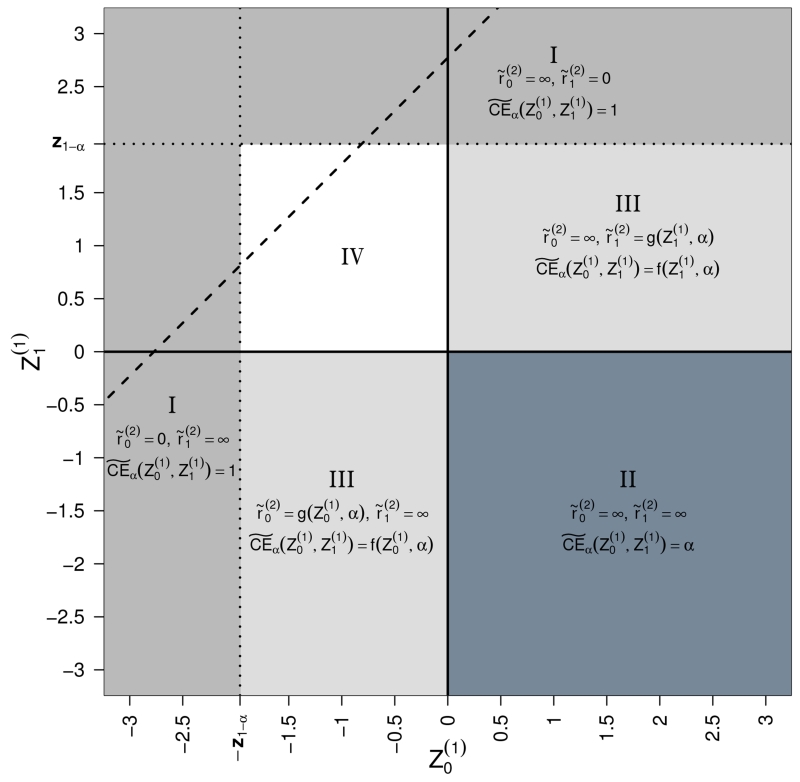

To simplify the integration (2) we can split it in several parts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Worst case scenarios in partitions of the (, )-plane.

I. For the strategy to yield a conditional type 1 error rate of 1 is given by and . In this case the first stage standardized treatment mean would suffice to reach significance in a test against the fixed value μ = 0. For and the numerator of the argument of the function Φ in formula (1) tends to a negative number and the denominator tends to 0 (see formula (1)). Hence the conditional error tends to 1. Similar arguments apply for , where the strategy and would lead to a conditional type 1 error rate of 1 (see areas I in Figure 1). The regions {} and {} are overlapping. The contribution to the maximum type 1 error rate over the two overlapping regions I is therefore 2α − α2.

In the subspace of region I where the maximum conditional type 1 error rate can also be yielded by setting because the test already rejects in the interim analysis. This is the corresponding subspace in region I above the dashed line in Figure 1 which indicates the rejection boundary in the interim analysis.

Note that in this region I the maximization of the conditional error in (1) with r(1) ≠ 1 leads to the same solution since for and or and the conditional error function does not depend on r(1).

II. For and (see rectangle II in Figure 1) obviously the largest conditional type 1 error rate achievable is by letting and (see Appendix A.2). This means that the first stage negative treatment effect will not play any role in the final test decision since it is overruled by the new large experiment with type 1 error rate α started at interim. Hence the contribution to the maximum overall type 1 error rate in the lower right quadrant of Figure 1 will be .

Again the same solution arises for r(1) ≠ 1.

III. We next look only at the half open strip and (the same result will apply for the strip and because of symmetry arguments, see areas III in Figure 1). Obviously in the strategy to maximize the type 1 error rate we take . Thus the optimization does not depend on the value of if (see Appendix A.3). For the value maximizing the conditional error rate is

The corresponding worst case conditional error function is the circular conditional error function of [1]:

Hence, integrating over between 0 and z1 − α, the total contribution to the overall maximum type 1 error rate in the two stripes III is given by

The same solution holds for r(1) ≠ 1, the arguments of the proof in the Appendix A.3 apply to this case as well.

IV. For the remaining white area IV in Figure 1 we used pointwise numerical optimization and numerical integration (using R-packages optim and integrate) to find the values of the worst case conditional type 1 error rate. Note that setting the derivatives of CEα with respect to and to zero leads to equations which cannot be solved analytically.

This is the only part of the sample space where the calculations differ for different values of the first stage allocation rate r(1). For example, the boundary for early rejection changes to and is not anymore symmetric around in this area. Figure 2 shows for varying values of r(1) and different α. Large differences between the solutions are only found for very low and very large values of r(1). The case of r(1) = 0 is discussed in Section 5 below.

Summing up the above results for r(1) = 1 the maximal conditional type 1 error rate is

where in the triangle {} which is the small triangle above the dashed line in the white area IV in Figure 1.

In summary, for α = 0.05 the maximum overall type 1 error rate is , for α = 0.025 it is and for α = 0.01 it is .

4 Constrained second stage sample sizes

The maximum overall type 1 error rate described above is calculated without imposing any constraints on the sample size adaptation of the second stage, so that we allow early rejection in the interim analysis and infinite sample sizes at the second stage. Here the lower boundaries for the sample size inflation factors have been and the upper boundaries for the control and treatment group respectively. However, in reality the second stage sample size is constrained. [17] derived formulas for the maximum conditional error function applying constraints on the sample sizes balanced before and after the interim analysis. In the following we provide numerical calculations if the allocation rate may be adapted after the interim analysis. Figure 3 shows the maximum conditional type 1 error rate for a varying upper boundary (allowing up to a 10 times larger second stage sample size as compared to the first stage in the treatment group) and different restrictions on the second stage sample size of the control group. We calculated the numbers by numerical optimization and integration over the interim sample space. The figure shows results for α = 0.01, 0.025 and 0.05. Clearly, the maximum overall type 1 error rate increases with increasing . It is important to realize that the maximum overall type 1 error rate strikingly increases when the second stage sample size can be smaller than the first stage sample size, in particular when allowing for early rejection in the interim analysis, i.e. setting the second stage sample size to 0 (dashed as compared to solid lines). The dashed lines show the maximum overall type 1 error rate when no sample size reduction at the second stage is allowed as compared to the first stage for the treatment and control group respectively () and . Clearly, if the maximum overall type 1 error rate is α since no adaptation is allowed for the second stage sample sizes (values at the dotted and dashed lines for in Figure 3). Allowing for early rejection () and not allowing sample size increase as compared to the first stage () would increase the maximum overall type 1 error rate to 0.0224 for α = 0.01 as well as to 0.0516 for α = 0.025 and to 0.0959 for α = 0.05 respectively. These are the values at the solid curves for in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Maximum overall type 1 error rate () for varying upper boundary for the sample size inflation factor in the treatment group. Solid lines: and (sample size decrease and early rejection possible); dashed lines: and (no sample size reduction in the second stage); dotted lines: and (sample size increase only in treatment group). α = 0.01 (black lines with squares), 0.025 (dark grey lines with triangles) and 0.05 (light grey lines with dots).

4.1 The motivating example revisited

We now investigate the scenario described in Section 2: There is no reason from the beginning to change the sample size in the control group because sufficient information of the safety on the control therapy is known from previous experiments. A larger sample size would be helpful to get more information on the arising safety issue in the experimental treatment group. However, external financial constraints do not allow an increase of the planned second stage sample size to more than threefold. A reduction of the sample size in the experimental treatment group is not considered since a certain amount on treatment safety is required.

Since stopping for futility has not been pre-planned to be used for constructing decision boundaries the example corresponds to the situation shown in Figure 3 with a fixed and . Here the maximum type 1 error rate assuming knowledge of the common effect size in the interim analysis of the two equally effective treatments is 0.0304 (see Figure 3). If a formal stopping for futility is included into the probability calculations, e.g. proceed to the second stage only if the interim estimate of the treatment difference points in the correct direction () the worst case type 1 error rate is 0.0294. The maximum is not reduced markedly by this rule since the conditional error in case of will be small. Only if we sharpen the condition for futility stopping to (with a standardized treatment difference not exceeding 0.735) would the above option of sample size adaptation lead to a maximal type 1 error rate not exceeding 0.025 in the conventional test.

These numbers may have different consequences. The strict experimenter may decide to use the above worst case conditional error rate approach to correct for the final decision boundary. Assuming that the constraint on the maximum second stage sample size does not depend on the observed outcome data, he would have to change the nominal error rate α in the final analysis to a value α′ = 0.0204 so that the worst case overall error rate for all possible second stage designs would not exceed the predefined 0.025. This price may be acceptable, since increasing the sample size gains power. Note however, that strictly this adjusted nominal error rate α′ would have to be applied as an upper bound for this flexible type of sample size reassessment even when no adaptation is performed. We do not believe that using the nominal significance level of 0.025 in the situation when no adaptations are performed in any realistic scenario will inflate the actual type 1 error rate. However, in case of changing the allocation ratios a strict preservation of the conditional error rate is not possible in practice because the rate depends on the unknown nuisance parameter and therefore cannot be calculated. Methods like conditioning on the sufficient statistics for the nuisance parameter (see [10]) or taking weighted averages over the unknown nuisance parameters in the interim analysis must be applied in this case (see [11]).

Another experimenter may argue that this adaptation is not related to any efficacy data and therefore he may safely stay with the conventional analysis at the end. However, since safety and efficacy may be correlated, this argument is not stringent. For methods allowing for correlation between outcome variables see e.g. [18]. In order to demonstrate that such an adaptation may not lead to a dramatic increase in the overall type 1 error rate even if efficacy data and the value of the nuisance parameter μ were known the experimenter may include the above calculations when summarizing the study outcome.

An R-program to calculate the maximum conditional error rate with or without constraints on the second stage sample sizes is available under http://statistics.msi.meduniwien.ac.at/index.php

5 Historical control group

Let us now consider the limiting case where the first stage has no treatment group (r(1) = 0). This case would apply, for example, if a recent sample under a standard treatment is available and will be included in the final analysis of the forthcoming experiment to compare a new treatment to the standard treatment (admittedly this would not be a sound and persuasive strategy in practice). We acknowledge that comparisons with historical controls requires some adjustment for potential confounders which for simplicity will not be considered here. The second stage sample sizes can again be chosen in an arbitrary way such that and for the treatment group (note that the second stage sample size of the treatment group has to be larger then 0 to allow a treatment-control comparison). Because of we present the formulas in terms of instead of , i = 0, 1. The conditional error can then be calculated as

| (3) |

(see Appendix A.4). The maximum overall type 1 error rate for this scenario can than be calculated by

| (4) |

where . Again, we tried to maximize the type 1 error rate allowing second stage sample sizes tending to 0 or to ∞ to show the most extreme inflation of the type 1 error rate.

Splitting the integration (4) into 3 parts {}, {} and {} and using similar arguments as before the analytic solution for the maximum overall type 1 error rate is the same as for the z-test with constant allocation ratios derived by [1], i.e. for α = 0.01, for α = 0.025 and for α = 0.05.

6 Discussion

We have calculated the maximum overall type 1 error rate for the z-test (comparing two normal means, common standard deviation known) that may be reached if the sample sizes per treatment arm can be modified in an interim analysis utilizing the treatment effects observed. [1] solved this problem under the restriction of identical allocation rates between the treatment groups before and after the interim analysis. In this case the solution only depends on the first stage z-statistics. If the reallocation ratio changes in the interim analysis the maximum type 1 error rate depends on the deviation of the observed estimates from the nuisance parameter involved (the unknown common effect of all the treatments under the null hypothesis). Hence in calculating the type 1 error rate under the worst case scenario we assume that the experimenter knows the nuisance parameter. This assumption appears unrealistic although there may be situations in practice where precise estimates may exist for the effect in the control group from historical data (and thus also for the nuisance parameter under the null hypothesis). We tried to find explicit solutions for the worst case choice of the second stage sample sizes for different interim outcomes. We are aware that allowing second stage sample sizes tending to 0 or ∞ is not a realistic scenario. However, it was our intention to show the most extreme inflation of the type 1 error rate. As a consequence the actual type 1 error rates resulting from changes in sample sizes per treatment group in the interim analysis when the estimates of the treatment effects are available in practice may be well below these worst case solutions. By considering constraints on these sample size we have investigated more realistic situations, e.g. when the second stage allocation ratio of treatment to control will never be below 1. Not surprisingly the option of reducing the pre-planned sample size in case of observed large treatment differences, in the most extreme case to allow rejection of the null hypotheses already in the interim analysis, has a major impact on the magnitude of the yielded type 1 error rate. We also looked at the rather hypothetical situation that only the control group is investigated before the interim analysis (”historical control”) which leads to the same solution as found by [1]. We did not look at situations with variance heterogeneity and other distributions than the normal distribution for the outcome variables because direct formulas for the conditional error are hardly accessible in these more general settings.

We have mentioned that response-adaptive randomization may be looked at as a special case of the types of adaptation considered in our paper. We have shown an example of how to use the calculations heuristically to account for such type of adaptations. This may be useful in applications, because in the presence of nuisance parameters, applying the principle of preserving the conditional type 1 error rate for the exact control of the overall type 1 error rate is not straightforward.

Acknowledgements

We thank Werner Brannath and Martin Posch for their helpful suggestions. We also thank an associate editor and two reviewers for their useful comments. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) no. P23167.

A Appendix

In the following we assume that the null hypothesis applies (μ0 = μ1 = μ).

A.1

In the final analysis after the second stage the test is based on the following global test statistic:

where , i = 0, 1, j = 1, 2, have independent standard normal distributions. If Z(2) is larger than z1−α we get a false positive decision, which leads to the following inequality:

Since and have independent standard normal distributions for every set of values r(1), , , and (and hence are independent of these quantities)

Hence the conditional error can be written as in formula (1).

A.2

The conditional error is maximized if the following expression is minimized (note that r(1) = 1):

| (5) |

In the rectangle and (area II in Figure 1) the second term is 0 or greater and tends to 0 if both . In the first term the denominator is at least as large as the numerator:

Equality can be achieved by letting and so that the first term tends to z1−α. Thus, the maximal conditional error for each and in this rectangle is 1 − Φ(z1−α) = α. Therefore the contribution to the maximum overall type 1 error rate of this quadrant {, } is .

A.3

If and (half of region III in Figure 1) then

| (6) |

Setting in (5) and using the result for the first term derived in the previous section it can be seen easily that for the conditional error is monotone in . For all and the conditional error has a maximum for . For we get for the conditional error

which is independent of and can be easily maximized in , as in [1], leading to

The corresponding worst case conditional error function is then the circular conditional error function . From (5) it follows that, given , the same solution can be yielded for every if which for given value of according to Appendix 2 is the maximum achievable over the whole strip. As a consequence for all the inequalities in (6) become equalities. Thus, the maximal conditional type 1 error rate over this area can be calculated as

see [1]. For reasons of symmetry, the same result can be achieved for the strip and where the optimal choice would be .

A.4

Assuming r(1) = 0, after the second stage the test is based on the following test statistic:

where , and are standard normal distributed. If Z(2) is larger than z1−α we get a false positive decision, which leads to the following inequality:

Since and have independent standard normal distributions, independently of ,, , we get (3) for the conditional type 1 error rate.

Footnotes

This article was published 2011 in Statistics in Medicine, Volume 30, Issue 14, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sim.4230/full

References

- [1].Proschan MA, Hunsberger SA. Designed extension of studies based on conditional power. Biometrics. 1995;51:1315–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bauer P. Multistage testing with adaptive designs. Biometrie und Informatik in Medizin und Biologie. 1989;20:130–148. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bauer P, Koehne K. Evaluations of experiments with adaptive interim analysis. Biometrics. 1994;50:1029–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lehmacher W, Wassmer G. Adaptive sample size calcualtions in group sequential trials. Biometrics. 1999;55:1286–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brannath W, Posch M, Bauer P. Recursive combination tests. JASA. 2002;97:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mueller HH, Schaefer H. Adaptive group sequential designs for clinical trials: combining the advantages of adaptive and of classical group sequential approaches. Biometrics. 2001;95:886–891. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mueller HH, Schaefer H. A general statistical principle for changing a design any time during the course of a trial. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:2497–2508. doi: 10.1002/sim.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Proschan MA. Sample size re-estimation in clinical trials. Biometrical Journal. 2009;51:348–357. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200800266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Posch M, Timmesfeld N, Koenig F, Mueller HH. Conditional rejection probabilities of students t-test and design adaptations. Biometrical Journal. 2004;46:389–403. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Timmesfeld N, Schaefer H, Mueller HH. Increasing the sample size during clinical trials with t-distributed test statistics without inflating the type I error rate. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;26:2449–2464. doi: 10.1002/sim.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gutjahr G, Brannath W, Bauer P. A general approach to the conditional error rate principle with nuisance parameters. Biometrics. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01507.x. in press. DOI: 10.1111/j.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Committee for Proprietary Medical Products (CPMP) Statistical principles for clinical trials. 1998. CPMP/ICH/363/96. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Reflection paper on methodological issues in confirmatory clinical trials planned with an adaptive design. 2007. CHMP/EWP/2459/02. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Friede T, Henderson R. Exploring changes in treatment effects across design stages in adaptive trials. Pharmaceutical Statistics. 2009;8:62–72. doi: 10.1002/pst.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hu F, Rosenberger WF. The theory of response-adaptive randomization in clinical trials. Wiley Interscience; New Jersey: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hung HM, Wang SJ, O’Neill RT. Challenges and regulatory experiences in non-inferiority trial design without placebo arm. Biometrical Journal. 2009;51:324–334. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200800219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Brannath W, Koenig F, Bauer P. Estimation in flexible two stage designs. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25:3366–3381. doi: 10.1002/sim.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stallard N. A confirmatory seamless phase II/III clinical trial design incorporating short-term endpoint information. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;29:959–971. doi: 10.1002/sim.3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]