In the direct pathway of allore-cognition, recipient T cells recognize intact donor major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on the surface of donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs), whereas the indirect pathway involves recognition of processed donor antigen presented in the context of self-MHC on the host’s own APCs (1, 2). Both pathways play important roles in the allograft response. Herein, we report on the kinetics of graft rejection when the alloantigen is presented by one of the pathways to B6.TEa.Rag-2−/− recipient mice whose T cells express a donor direct or indirect pathway responsive transgenic T-cell receptor (TCR) at a given time. This TEa-TCR recognizes the IE-alpha peptide 52–68 (ASFEAQGLANIAVDKA) presented in the context of IAb. C57BL/6.Rag-2−/− mice expressing the TEa transgenes were produced by crossing C57BL/6.Rag-2−/− and TEa transgenic mice (3) (a gift from Randy Noelle at Dartmouth University, Hanover, NH).

Tail skin from BALB/c (IAd/IEd), CB6F1(IAbd/IEd), or C57BL/6(IAb/IE−) mice were grafted onto B6.TEa. Rag2−/− mice. BALB/c dendritic cells (DCs) produce IEd 52–68 peptide but cannot present it directly to B6.TEa. Rag2−/− mice T cells. The IEd 52–68 peptide must be processed by the B6.TEa.Rag2−/− IAb DCs before presentation to its T cells allowing for indirect pathway of alloantigen presentation. Conversely, CB6F1 skin graft alongside indirect antigen presentation allows for direct antigen presentation as CB6F1 DCs can both produce IEd 52–68 peptide and directly present it to TEa Rag2−/− T cells in conjunction with their own IAb molecules. Therefore, we studied the kinetics of rejection of BALB/c or CB6F1 donor strain skin transplants by B6. TEa.Rag2−/− mice to study direct and indirect alloantigen presentation. In comparison with CB6F1 donor graft, rejection of BALB/c grafts were delayed by 6 days (P=0.0067; Fig. 1A). Hence, these data indicate that indirect alloantigen presentation alone leads to graft rejection albeit graft rejection is significantly delayed. Natural killer (NK) cells kill allogeneic donor APCs (4), and anti-NK1.1 treatment strengthens rejection in some (4) but not all MHC incompatible skin allograft strain combinations (5). Treatment did not alter mean survival time in this Balb/C to Tea-TCR tg C57BL/6 model (unpublished observations). Indeed in accordance with our work, anti-NK1.1 treatment did not affect graft rejection by C57BL/6 recipients grafted with Balb/C skin (5). Moreover, the magnified frequency of donor-reactive T cells in the TEa-TCR-Tg host is almost certain to make the NK effect on donor APCs less crucial to graft acceptance.

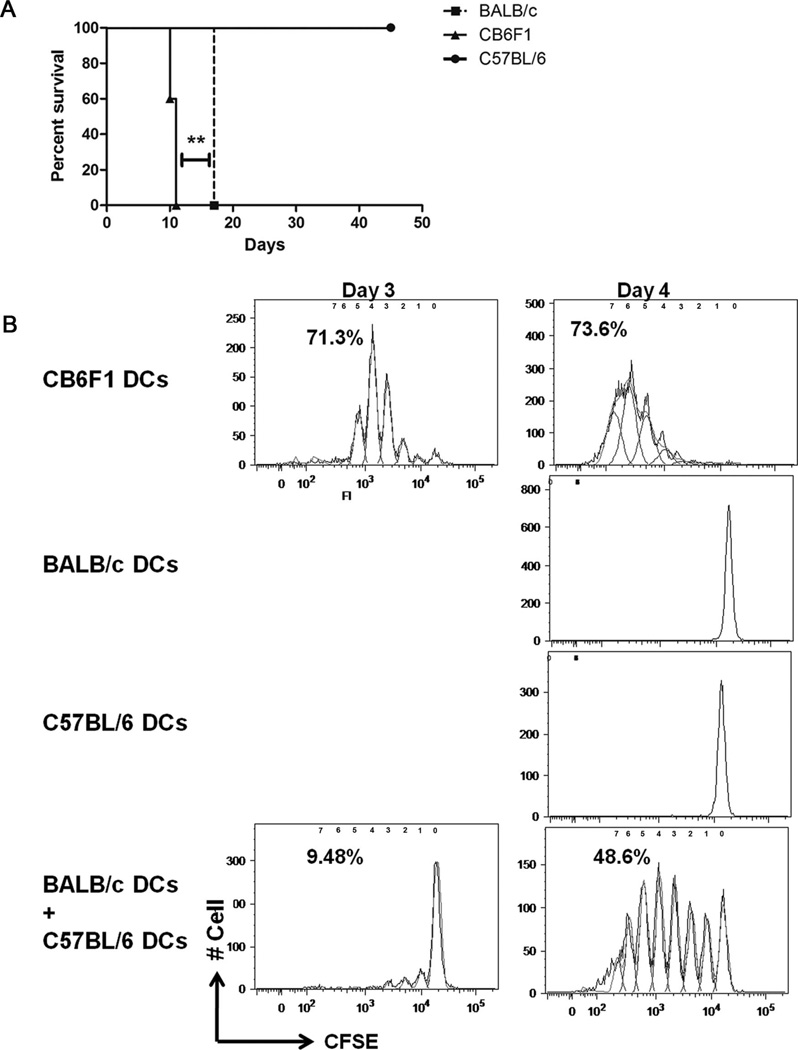

FIGURE 1.

(A) In comparison with CB6F1 donor skin grafts, there is a delay in rejection of BALB/c donor skin grafts by B6.TEa.Rag2−/− recipients (n≥4). (B) Delayed proliferation of B6.TEa.Rag2−/− CD4+ T cells when the alloantigen is presented by the indirect pathway (n=3).

We hypothesized that the delay in graft rejection is due to a delayed onset of immune response primarily due to delayed T-cell activation. To test this hypothesis, we studied in vitro B6.TEa.Rag2−/− T-cell proliferation in the mixed leukocyte reaction using CB6F1, BALB/c, or C57BL6 DCs. When activation of CFSE-labeled B6.TEa. Rag2−/− CD4 cells was triggered by CB6F1 DCs, the T cells start proliferating as early as day 2, and by day 4, approximately 75% of the cells were proliferating (Fig. 1B). In comparison, proliferation was not discerned using syngeneic C57BL/6 DCs or allogeneic BALB/c DCs as stimulator cells (Fig. 1B). However, when both BALB/c and C57BL/6 DCs are added to the same well to allow indirect antigen presentation, it leads to T-cell proliferation albeit with a delay as proliferation was noticed on day 3 with approximately 10% cells proliferating (Fig. 1B). Hence, in this particular experimental setting, these in vitro data are in line with our hypothesis, suggesting a delay in T-cell activation and proliferation as one of the many possible mechanisms leading to a delay in graft rejection. In a distinct adoptive transfer model study, where direct and indirect pathway T cells were injected into immune compromised mice, it has been shown that indirect pathway CD4 T cells proliferate more rapidly (6). The difference in observations can be attributed to the peculiarity of each model, and the observations cannot be generalized. We appreciate that the TEa-TCR transgenic model does not allow an analysis of the frequency of alloreactive T cells committed to the direct or indirect pathways. But the peculiarity of this model allows study of both direct and indirect pathway alloantigen recognition by a single clone of T cells. Thus, this TEa-TCR Tg model that is a reductionist model with a single clone of T cells able to mount antidonor responses allows understanding the mechanism by which delayed graft rejection occurs when antigen is presented only through the indirect pathway.

It is well known that activation through the indirect pathway alone is sufficient for allograft rejection, but the rejection is significantly delayed. The classical work by Auchincloss et al. (7) using MHCII-deficient donor mice demonstrated the importance of indirect allorecognition alone in graft rejection. It is traditionally believed that direct alloreactivity is the driving mechanism behind early acute graft rejection. But the direct response subsides as the donor antigen disappears, meanwhile the indirect alloresponse appears and persists causing chronic rejection. Study in our specific TCRTg model is in line with this belief where indirect alloantigen alone can lead to delayed rejection. Our in vitro studies in this particular experimental setting further suggest that the time lag for foreign antigen processing and presentation by self-MHC on recipient APCs may delay the T-cell proliferation and hence indirect alloresponse-mediated rejection. Various studies have shown results contrary to our study, and we attribute the difference in these findings to the peculiarity of the different models studied and believe that no generalization can be drawn from any of these studies including ours.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NIHP0AIGF41521 and NIH-P01 AI073748 (T.B.S.).

Footnotes

S.G., S.B., T.B.T., and J.J.K. contributed to performance of the research; S.G., S.B., T.B.S., and J.J.K. contributed to designing of the research; and S.G., T.B.S., and J.J.K. contributed to writing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bolton EM, Bradley JA, Pettigrew GJ. Indirect allorecognition: Not simple but effective. Transplantation. 2008;85:667. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181664db3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gokmen MR, Lombardi G, Lechler RI. The importance of the indirect pathway of allorecognition in clinical transplantation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:568. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grubin CE, Kovats S, deRoos P, et al. Deficient positive selection of CD4 T cells in mice displaying altered repertoires of MHC class II-bound self-peptides. Immunity. 1997;7:197. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu G, Xu X, Vu MD, et al. NK cells promote transplant tolerance by killing donor antigen-presenting cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1851. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trambley J, Bingaman AW, Lin A, et al. AsialoGM1+ CD8+ T cells play a critical role in costimulation blockade–resistant allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1715. doi: 10.1172/JCI8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan TV, Jaigirdar A, Hoang V, et al. Preferential priming of alloreactive T cells with indirect reactivity. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:709. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auchincloss H, Jr, Lee R, Shea S, et al. The role of “indirect” recognition in initiating rejection of skin grafts from major histo-compatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]