Introduction

The incidence of thyroid cancer is increasing with an estimated 44,670 new cases diagnosed in 2010. Approximately 1 in 111 men and women will develop thyroid cancer in their lifetime. The incidence in women is 3-fold higher than in men and the median age is 49 years. However, the prognosis is excellent with an overall 5-year survival of 97.3% and stable mortality rates over time (1).

The increase in incidence was recently studied by analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data and may be due to improved detection of small (<2 cm) papillary thyroid cancers (2). Coincident with the increase is widespread utilization of ultrasound and fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). Long term follow-up is needed to determine if early detection will eventually have a beneficial impact.

Although up to 70% of people will have a thyroid mass visualized on ultrasound, the overall risk of thyroid cancer in a nodule is only ~5%. As discussed in other chapters, evidence-based clinical management algorithms guide the evaluation. FNAB is highly accurate and specific but 10–15% of the results will fall into the indeterminate category, which now includes three subsets: follicular lesion of undetermined significance (FLUS), follicular or oncocytic neoplasm, and suspicious for malignancy results (3). Thyroidectomy is currently often required for definitive diagnosis of indeterminate cytology results. The risks of thyroid surgery include morbidity and associated health care costs. Imaging characteristics in addition to other diagnostic modalities can help define malignancy risk and guide extent of surgery.

Indications for Surgery

A surgical evaluation is usually prompted by clinical history, FNAB results, and/or patient request. Radiation exposure and family history in first-degree relatives are two well-documented risk factors for differentiated thyroid cancer. Exposure to nuclear fallout or therapeutic ionizing radiation to the head and neck are two of the most common types of radiation exposure that increase the risk of thyroid cancer. The latency period is usually 25–30 years, but the effects can be significant for up to 40 years (4, 5). Radiation exposure can also increase the risk of primary hyperparathyroidism and affected patients should be screened for both disorders. A number of inherited syndromes can be associated with thyroid cancer including Cowden syndrome (macrocephaly, mucocutaneous lesions, and breast cancer), Carney complex type 1 (cardiac myxoma, skin and mucosal pigmentations), and familial adenomatous polyposis (colon cancer) (6). In addition, if there is a family history of thyroid cancer, hypercalcemia, mucosal lesions, and/or hypertension secondary to pheochromocytoma, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 is a consideration. A fasting serum calcitonin should be obtained preoperatively to evaluate for C-cell hyperplasia and medullary thyroid carcinoma.

A clinical history of an enlarging thyroid mass increases the concern for malignancy. On physical exam, an immobile and firm thyroid nodule is also worrisome. Routine evaluation should also assess for dysphagia, positional dyspnea, orthopnea, anterior neck discomfort, hoarseness, tracheal deviation, lymphadenopathy, and the presence of contralateral thyroid nodules. Supine dyspnea that is relieved by positional change and/or an inability to palpate the inferior aspect of the thyroid gland, should raise the concern for a substernal component. A CT neck without intravenous contrast is usually obtained to assess the caudal extent of the thyroid gland (Figure 1). Goiter extending below the aortic arch may require a partial sternal split for complete resection. A history of sleep apnea or significant thyromegaly at the thoracic outlet on examination should also prompt a non-contrasted CT scan to evaluate for tracheal compression that could affect both extent of surgery and method of anesthesia induction (Figure 2). A CT neck with contrast is helpful only if the relationship of the thyroid mass to adjacent vascular structures needs to be better delineated.

Figure 1.

Coronal section of a CT scan of the chest with intravenous contrast obtained for a 72 year old woman who presented with acute shortness of breath. Her large thyroid goiter is predominantly substernal and not appreciated on physical exam. Although a thoracic surgeon was available for a possible sternotomy, her thyroid was successfully mobilized and resected through a 5cm cervical incision.

Figure 2.

Transverse section of a CT scan of the neck without intravenous contrast obtained of a 49 year old woman who presented with a large cervical goiter that was noted on routine physical exam. Although she was asymptomatic, her enlarged thyroid gland was causing 65% tracheal compression and she required an awake fiberoptic intubation prior to general anesthesia for her thyroidectomy.

As discussed in previous chapters, a neck ultrasound is routinely obtained to evaluate thyroid nodule size and characteristic. Cervical lymphadenopathy should also be concurrently evaluated. FNAB is the initial diagnostic test and determines subsequent clinical management. Diagnostic thyroidectomy is indicated for FNAB results in either the indeterminate or positive for malignancy categories (Figure 3). Persistently inadequate FNAB results also prompt diagnostic thyroid surgery. In addition, clinically or sonographically suspicious nodules should be further evaluated, even if FNAB results are initially benign. Patients with significant risk factors for thyroid cancer who have a dominant (>1 cm) thyroid nodule, symptomatic thyromegaly, tracheal compression, and/or substernal goiter that is unable to be evaluated completely with FNAB or US should also be considered for thyroidectomy (7).

Figure 3.

(a) A transverse neck ultrasound image of a 38 year old woman with a solitary 2.5 cm right thyroid nodule (arrow) that has a hypoechoic rim and hypervascularity. A follicular neoplasm was diagnosed after FNAB. (b) Following thyroid lobectomy, a 2 cm follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinoma (arrow) was diagnosed and she went on to receive completion thyroidectomy within 2 weeks.

Size has been shown in a number of studies to be associated with both malignancy and false negative benign FNAB results. Meko et al first reported an overall malignancy rate of 21% for thyroid nodules ≥3 cm and a 30% false negative rate for benign FNAB results (8). Utilizing a study design recently described to be more accurate at determining the true false negative FNAB results (9), a larger investigation described 223 consecutive patients for whom the presence of a ≥4 cm thyroid mass was considered an independent indication for thyroidectomy, and found that 26% had clinically significant thyroid cancer. Among the patients with ≥4 cm thyroid nodules who had benign preoperative FNAB results, 13% had a clinically significant thyroid cancer within the biopsied nodule (10). Because of the high false negative rate associated with benign FNAB in large nodules, we currently perform thyroidectomy for nodules ≥ 4cm, regardless of FNAB results.

Extent of Initial Thyroidectomy

The extent of initial thyroidectomy depends on whether the diagnosis of thyroid cancer can be determined on FNAB. Patients with FNAB results positive for thyroid carcinoma should be counseled about the associated low but real false positive rate (3). In the absence of an FNAB result positive for malignancy, the decision for thyroid lobectomy versus total/near total thyroidectomy depends on clinical characteristics and risk of malignancy as outlined below. The minimum operation at initial operation should be a complete lobectomy and isthmusectomy with the margin of resection being the junction of the isthmus to the contralateral lobe. A partial lobectomy or ‘nodulectomy’ puts the ipsilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve at increased risk if a reoperation is required, and partial lobectomy has thus been abandoned. Although the main benefit of an initial thyroid lobectomy is to potentially prevent chronic postoperative hypothyroidism, replacement l-thyroxine therapy is still required in 25–40% of patients (11). Initial lobectomy also prevents the risk of postoperative hypoparathyroidism. However, if thyroid cancer is diagnosed on final histopathology, a completion thyroidectomy may be necessary. Completion thyroidectomy unfortunately exposes the patient to a second general anesthetic as well as to the higher complication risks associated with reoperation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Operative risks associated with thyroid surgery

| Total Thyroidectomy | Thyroid Lobectomy | Completion Thyroidectomy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury | |||

| Unilateral | 1–3% | 1–3% | 1–3% |

| Bilateral | <1% | 0% | 0% |

| Superior laryngeal nerve injury | 5–10% | 5–10% | 5–10% |

| Permanent hypoparathyroidism | 0.5–3% | 0% | 0.5–3% |

| Cervical hematoma | 0.5–1% | 0.5–1% | 0.5–1% |

| Hypothyroidism | 100% | 20–40% | 100% |

Total or near-total thyroidectomy leaves less than 50 mg of tissue at the ligament of Berry and is considered the initial surgical procedure of choice for known thyroid cancers >1 cm in size. In all patients with thyroid cancer, the purpose of thyroidectomy is to remove the primary tumor, minimize treatment-related morbidity, determine accurate staging, facilitate treatment with radioactive iodine when indicated, facilitate longterm surveillance, and minimize the risk of recurrence and metastastic disease (7). Associated abnormal lymphadenopathy is also resected, if present. A subtotal thyroidectomy which leaves >1 g of tissue is not a desirable procedure for thyroid cancer.

Initial total thyroidectomy should also be considered if there is a high risk of thyroid cancer such as with suspicious findings or significant atypia seen on biopsy, a close family history of thyroid cancer, a history of therapeutic radiation exposure such as whole body radiation for lymphoma, and >4 cm nodules with indeterminate (either oncocytic cell or follicular neoplasm) FNAB results. Other relative indications for an initial total thyroidectomy include a pre-existing history of hypothyroidism, a contralateral dominant (>1 cm) nodule, an elevated calcitonin, or a family history of a genetic predisposition syndrome. After adequate counseling, patients may also elect to undergo an upfront total thyroidectomy and avoid the potential for a second operation (7).

If thyroid cancer is diagnosed after thyroid lobectomy, completion thyroidectomy is subsequently performed to facilitate use of radioactive iodine ablation for therapy and staging, and is also recommended for tumors types with a high risk of multifocality (7). Unifocal papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (<1 cm) is associated with excellent long-term survival and in the absence of aggressive histopathologic factors such as extrathyroidal extension or lymph node metastasis, a lobectomy alone is currently considered adequate treatment. In a retrospective study of greater than 50,000 PTC patients from the National Cancer Data Base, total thyroidectomy compared to lobectomy was associated with improved 10-year local recurrence rates (7.7% vs 9.8%) and 10-year survival (98.4% vs. 97.1%) except among patients with PTC <1 cm (12). Currently, the recommendation of the American Thyroid Association is to perform completion thyroidectomy for all patients who would have undergone total thyroidectomy if the diagnosis of thyroid cancer was known prior to initial surgery (7). Follicular carcinoma that is diagnosed in older (>40 years old) patients, has vascular invasion, or is widely invasive, is associated with a poorer prognosis, and patients should undergo completion thyroidectomy (13, 14). Oncocytic (Hürthle cell) carcinoma can be multifocal and several small studies have suggested that prognosis is improved following total thyroidectomy (15). Completion thyroidectomy is usually performed either immediately (<2 weeks) after lobectomy, or 6–8 weeks following the initial procedure to allow resolution of early postoperative inflammatory changes. Completion surgery should always be preceded by laryngoscopy to evaluate vocal cord function.

Lymphadenectomy

Cervical lymph node metastasis in thyroid cancer is present in 20–90% of patients at the time of presentation depending on the detection method. However, clinically apparent metastases are seen in 10% of patients, at most (16, 17). The prognostic significance of lymph node metastases is controversial, but it is clear that the presence of gross nodal disease is associated with local recurrence (18). Cervical lymph node disease is best evaluated by preoperative US and, when present, is confirmed by FNAB for cytology and/or thyroglobulin measurement of the aspirate. If indicated, a functional, compartment oriented neck dissection is thought to reduce the risk of local recurrence and is the surgical approach favored over ‘berry-picking’.

Central Compartment

Studies have shown that the central compartment (level VI) is usually the first site of metastatic disease. The central compartment is defined by the boundaries of the hyoid bone (superiorly), carotid arteries (laterally), superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia (anteriorly), and deep layer of the deep cervical fascia (posteriorly). On the right, the innominate artery defines the inferior boundary while the equivalent plane defines this boundary on the left. A unilateral central compartment lymph node dissection includes the prelaryngeal (Delphian), pretracheal, in addition to either the right or left paratracheal lymph nodes while a bilateral dissection includes both paratracheal nodal basins (19).

In the presence of clinically evident metastases, a therapeutic central compartment lymph node dissection is recommended. Because the thyroid gland itself can obscure an accurate assessment, imaging can frequently miss abnormal lymph nodes. Routine intraoperative assessment of central compartment lymph nodes by palpation and visual inspection is usually performed.

Whether or not to perform a prophylactic central compartment lymph node dissection is controversial. Routine ipsilateral central compartment dissection has been shown to reduce postoperative thyroglobulin levels, but long term prospective studies have yet to show that routine dissection leads to improvements in either recurrence or disease specific mortality (20). Prophylactic central neck dissection may lead to more accurate staging and risk stratification allowing in the future for a selective approach to radioactive iodine ablation (21). However, the risk of hypoparathyroidism appears to be more frequent after thyroidectomy with central compartment neck dissection than after thyroidectomy alone and this risk, as well as the risk of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, should be considered when deciding whether to perform prophylactic central neck dissection (22).

Lateral Compartment

A lateral compartment can have metastatic disease, even in the absence of central compartment disease (23). The lateral compartment is defined by the boundaries of the internal jugular vein (medially), trapezoid muscle (laterally), subclavian vein (inferiorly), and hypoglossal nerve (superiorly). The lymph nodes within the lateral compartment are further separated by anatomic boundaries defining levels I–V. The most common levels involved with metastatic thyroid cancer are II–IV. In the absence of gross involvement, a modified neck dissection which preserves the internal jugular vein, sternocleidomastoid, spinal accessory and phrenic nerves is usually performed for thyroid cancer.

Little controversy exists in the management of the lateral compartment. Therapeutic lateral neck dissection is indicated for patients with clinically or radiographically evident lymph node metastases. Prophylactic lateral neck dissection has never been shown to improve long term outcomes and is not recommended for patients with differentiated thyroid cancers (7).

Surgical Techniques

Thyroidectomy is usually performed under general anesthesia, although some centers perform thyroidectomy in selected patients after cervical block and intravenous sedation only (24). After induction of anesthesia, the neck is gently extended to expose the anterior surface. Patients with a history of cervical stenosis or symptoms such as peripheral radiculopathy after prolonged neck extension should have a preoperative MRI of the neck to evaluate the cervical spine for possible cord compression. During patient positioning, somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) monitoring can be used to evaluate for position-related cord compression after neck extension.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring can be utilized during thyroidectomy; however, large studies have not shown that routine use reduces nerve injury rates (25). Nerve monitoring may be most helpful in reoperative cases or in massive goiter resections where the anatomy may be obscured. Some advocate a baseline laryngeal examination for all patients prior to surgery. Absolute indications for preoperative assessment of vocal cord function include preoperative voice changes, massive goiter, and a history of prior surgical surgery of any type associated with recurrent laryngeal nerve injury such as (in approximate decreasing order of occurrence), anterior cervical spine fusion, carotid surgery, thoracic or cardiac surgery, and prior thyroid or parathyroid resection.

A standard thyroidectomy incision is short, measuring 4–5 cm, although this can vary widely by patient body mass index and thyroid volume (26). Parathyroid glands are gently preserved in situ on their vascular pedicle but if found to be adherent to the thyroid and resected, or if appearing nonviable, they should be autotransplanted into the ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid muscle. Intraoperative frozen section is utilized selectively if results would change the operative management, such as during lobectomy if there is suspicion for thyroid cancer or if there is concern for anaplastic thyroid cancer or thyroid lymphoma. Meticulous hemostasis is obligatory. A cervical drain is no longer routinely placed except after lateral neck dissection, due to the risk of lymphatic and/or chylous leak with that procedure.

Minimally invasive thyroidectomy is a type of surgical approach which can reduce the surgical incision to 1.5–2 cm in selected patients. Candidates for this technique include patients with solitary nodules <3 cm or a small multinodular goiter (total estimated thyroid volume on US of ≤25 mL). Absolute contraindications include patients undergoing reoperation or with large multinodular goiter, locally invasive thyroid cancer, or prior neck radiation. The presence of Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are relative contraindications due to the higher risk of intraoperative bleeding and associated inflammatory changes. Miccoli, who pioneered the most commonly used technique, recently estimated that only 10–15% of patients undergoing thyroidectomy in his practice are candidates for this approach (27).

In order to avoid a cervical incision completely, another option is use of robotic assistance to endoscopically resect the thyroid either through a transaxillary and/or periareolar approach. The largest series is from Chung who has performed transaxillary robot-assisted thyroidectomy in over 1000 patients either using a single axillary incision or with an anterior chest wall counterincision. They report hematoma, hypoparathyroidism and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury rates that are equivalent to standard thyroidectomy, but because the technique requires elevation of subcutaneous tissue flaps to approach the thyroid, additional reported complications include brachial plexus injury, chyle leak, seroma formation, and lengthy operation. Candidates for the robotic approach include thin patients with an anteriorly situated thyroid nodule ≤2 cm, and this approach is inappropriate for patients with BMI >35, deep or large thyroid lesions, prior neck surgery, Graves’ disease, extrathyroidal tumor invasion, or bulky lateral lymph node metastases (28).

After standard thyroid lobectomy, patients can be safely discharged on the same day as surgery as long as no cervical hematoma is evident on examination. Length of stay after total thyroidectomy is generally ~ 1 day. Postoperative l-thyroxine supplementation is initiated either immediately after surgery or after pathology results are available. The dose depends on the method and need for postoperative radioactive iodine ablation.

Complications

Complication rates after thyroidectomy are typically low. Sosa et al. demonstrated inverse relationships between surgeon volume and complication rate, length of hospital stay, and hospital charges (29). Overall complication rates after thyroidectomy are 5–7%. The most concerning and acute complications compromise the patient’s airway and include either bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury or post-operative hematoma.

A unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury occurs in 1–3% of patients in most surgical series. If there is intraoperative concern for a nerve injury, then a lobectomy alone should be performed until a functional assessment of the nerve can be carried out. If transected, primary neurorrhaphy of the recurrent laryngeal nerve may preserve laryngeal muscle tone and prevent atrophy of the vocal fold. The majority of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsies are transient. Postoperative symptoms after unilateral paresis depend on the degree of medialization of the immobile vocal fold, which can change over time. Occasionally, patients can be asymptomatic but other symptoms include hoarseness, weak cough, dyspnea especially while speaking, and dysphagia to thin liquids. Laryngeal electromyography can provide some prognostic information. Temporizing procedures include non-invasive strategies such as a chin tuck maneuver to the ipsilateral side to prevent aspiration and/or more invasive procedures to medialize the vocal fold such as injection with calcium hydroxylapatite. If the palsy does not recover in 6 months, a permanent intervention can be considered such as an autologous fat laryngoplasty or surgical thyroplasty. Although rare, bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis is a serious life-threatening problem in which hoarseness and aspiration are inversely proportional to obstruction of the tracheal air column. If a patient has significant stridor immediately after total thyroidectomy and the airway is found to be compromised, a tracheostomy is necessary.

Neck hematoma occurs in 0.5–1% of patients following thyroidectomy. To avoid this potentially life-threatening complication, anticoagulants and anti-platelet medications including low-dose aspirin are routinely stopped prior to surgery. Patients who resume these medications after surgery do not have a significantly higher rate of hematoma. The diagnosis of cervical hematoma requiring operative evacuation can be determined by physical exam and should be apparent well before airway compromise is clinically evident. Hematoma is never observed nonoperatively. Following urgent or emergent reoperation for hematoma, upper airway edema can be significant and careful assessment of airway patency should be performed before extubation. Imaging such as US, can sometimes be helpful in the delayed postoperative setting to differentiate between seroma formation and routine incisional changes.

Permanent hypoparathyroidism rates after total thyroidectomy are 0.5–3%, but transient hypocalcemia can be seen in up to 15% of postoperative patients. To diminish the usually temporary effects of parathyroid gland dissection, calcium supplementation is routinely prescribed for all patients after total thyroidectomy, and this intervention also cushions the management of the rare patient who goes on to develop hypoparathyroidism. Peripheral or perioral paresthesias are the most sensitive indicator of hypocalcemia. Chvostek’s sign is less sensitive as it is frequently seen preoperatively and in patients with normal calcium levels after thyroidectomy. The diagnosis of hypoparathyroidism requires the combined presence of severe hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and undetectable PTH levels. Patients with hypoparathyroidism and poor oral calcium absorption from prior gastric bypass surgery, celiac sprue, or chronic vitamin D deficiency from other causes, may require readmission for intravenous calcium supplementation until optimal oral calcium and vitamin D supplementation doses can be determined.

Voice changes in the absence of recurrent laryngeal nerve paresis have been documented after thyroid surgery in up to 30% of patients (30). The most common etiology is injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (the “opera-singer’s nerve”). Ligation of the superior pole vessels close to the thyroid capsule can help prevent this injury. Fibrosis of the cricothyroid muscle can also contribute to voice alterations but is difficult to diagnose. Rarely, acute dysphagia may result from pharyngeal perforation caused by esophageal instrumentation by temperature probes or oral-gastric tubes. Crepitance is suggestive; in addition to urgent cross-sectional imaging, a swallow study and bronchoscopy should be performed. Dysphagia described as a globus sensation can be observed and may persist for up to a year after surgery. For chronic dysphagia, a multidisciplinary management approach is effective and includes careful patient counseling, voice therapy, and exclusion of other possible etiologies. We have found that firm daily anterior cervical massage performed for 3–6 months postoperatively not only minimizes globus sensation but also markedly improves the cosmetic appearance of the scar. Wound infection is quite rare.

Recurrent Disease

Cancer recurrence occurs in 5–20% of thyroid cancer patients and is typically diagnosed by detectable thyroglobulin levels following thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine ablation. Surgery is indicated if the recurrence is (1) large enough to be radiographically apparent and (2) confirmed by cytologic findings after FNAB or elevated thyroglobulin levels in the aspirate. The most common location of surgically-resectable disease is in the central compartment. Because of fibrosis and anatomy alterations in a previously operated field, the risks of reoperation including nerve injury and permanent hypoparathyroidism are significantly higher. Needle localization can be one method of preventing operative failure (31). The use of ultrasound localization in the preoperative holding area to directly mark the area of recurrence is another less invasive technique to help guide the reoperation and can effectively reduce postoperative thyroglobulin levels (32). Lateral neck recurrences should be managed with a compartment oriented dissection, if not previously performed.

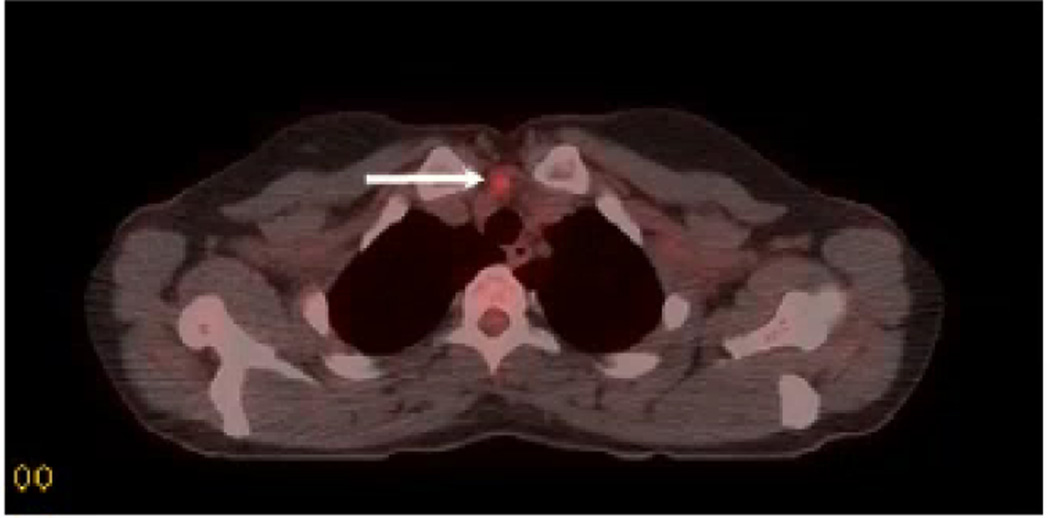

18FDG-PET can be useful in patients with thyroglobulin elevation who do not have evidence of disease on either US or whole body iodine scan (Figure 4). PET has an overall sensitivity of 50–70% and the sensitivity increases as the thyroglobulin level increases. No significant differences appear to occur when the study is obtained with or without TSH-stimulation (33).

Figure 4.

Transverse section of a fused CT-PET scan obtained for a 29 year old woman with a history of metastatic papillary thyroid cancer initially treated with total thyroidectomy, bilateral central compartment and bilateral lateral compartment lymphadenectomies followed by radioactive iodine ablation. A rising thyroglobulin level prompted whole body I131 scan and neck ultrasound, both of which were negative. Subsequent PET scan demonstrated a single focus of FDG-avidity in the upper mediastinum. After an uneventful reoperative cervical exploration and resection of the nodule, recurrent papillary thyroid cancer was confirmed.

Conclusion

Surgery is often needed to diagnose thyroid cancer, but is also the initial therapeutic modality. A number of current imaging techniques are important for the appropriate management of patients undergoing thyroid surgery and are particularly informative for thyroid nodule characterization to assist in risk stratification and to determine extent of surgery.

References

- 1.Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Cronin K, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2007. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973–2002. JAMA. 2006;295:2164–2167. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baloch ZW, LiVolsi VA, Asa SL, Rosai J, Merino MJ, Randolph G, et al. Diagnostic terminology and morphologic criteria for cytologic diagnosis of thyroid lesions: A synopsis of the national cancer institute thyroid fine-needle aspiration state of the science conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:425–437. doi: 10.1002/dc.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider AB, Ron E, Lubin J, Stovall M, Gierlowski TC. Dose-response relationships for radiation-induced thyroid cancer and thyroid nodules: evidence for the prolonged effects of radiation on the thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:362–369. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.2.8345040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kikuchi S, Perrier ND, Ituarte P, Siperstein AE, Duh QY, Clark OH. Latency period of thyroid neoplasia after radiation exposure. Ann Surg. 2004;239:536–543. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000118752.34052.b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemminki K, Eng C, Chen B. Familial risks for nonmedullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5747–5753. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1167–1214. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meko JB, Norton JA. Large cystic/solid thyroid nodules: A potential false-negative fine-needle aspiration. Surgery. 1995;118:996–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80105-9. discussion 1003–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tee YY, Lowe AJ, Brand CA, Judson RT. Fine-needle aspiration may miss a third of all malignancy in palpable thyroid nodules: a comprehensive literature review. Ann Surg. 2007;246:714–720. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180f61adc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCoy KL, Jabbour N, Ogilvie JB, Ohori NP, Carty SE, Yim JH. The incidence of cancer and rate of false-negative cytology in thyroid nodules greater than or equal to 4 cm in size. Surgery. 2007;142:837–844. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.08.012. discussion 844.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHenry CR, Slusarczyk SJ. Hypothyroidism following hemithyroidectomy: incidence, risk factors, and management. Surgery. 2000;128:994–998. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.110242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Linn JG, et al. Utilization of total thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid cancer in the United States. Surgery. 2007;142:906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow SM, Law SC, Mendenhall WM, et al. Follicular thyroid carcinoma: prognostic factors and the role of radioiodine. Cancer. 2002;95:488–498. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carling T, Udelsman R. Follicular neoplasms of the thyroid: what to recommend. Thyroid. 2005;15:583–587. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald MP, Sanders LE, Silverman ML, Chan HS, Buyske J. Hürthle cell carcinoma of the thyroid gland: prognostic factors and results of surgical treatment. Surgery. 1996;120:1000–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grebe SK, Hay ID. Thyroid cancer nodal meatastases: biologic significance and therapeutic considerations. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1996;5:43–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loh KC, Greenspan FS, Gee L, Miller TR, Yeo PP. Pathological tumor-node-metastasis (pTNM) staging for papillary and follicular thyroid carcinomas: a retrospective analysis of 700 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3553–3562. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zavdfudim V, Feurer ID, Griffin MR, Phay JE. The impact of lymph node involvement on survival in patients with papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. Surgery. 2008;144:1070–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Thyroid Association Surgery Working Group; American Association of Endocrine Surgeons; American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; American Head and Neck Society. Carty SE, Cooper DS, Doherty GM, et al. Consensus statement on the terminology and classification of central neck dissection for thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1153–1158. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sywak M, Cornford L, Roach P, Stalberg P, Sidhu S, Delbridge L. Routine ipsilateral level VI lymphadenectomy reduces postoperative thyroglobulin levels in papillary thyrdoi cancer. Surgery. 2006;140:1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonnet S, Hartl D, Leboulleux S, et al. Prophylactic lymph node dissection for papillary thyroid cancer less than 2 cm: implications for radioiodine treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1162–1167. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazzaferri EL, Doherty GM, Steward DL. The pros and cons of prophylactic central compartment lymph node dissection for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2009;19:683–689. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gimm O, Rath FW, Dralle H. Pattern of lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid carcinoma. British Journal of Surgery. 1998;85:252–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LoGerfo P, Ditkoff BA, Shabot J, Feind C. Thyroid surgery using monitored anesthesia care: an alternative to general anesthesia. Thyroid. 1994;4:437–439. doi: 10.1089/thy.1994.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angelos P. Recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring: state of the art, ethical, and legal issues. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:1157–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunaud L, Zarnegar R, Wada N, Ituarte P, Clark OH, Duh QY. Incision length for standard thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy: when is it minimally invasive? Arch Surg. 2003;138:1140–1143. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.10.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miccoli P, Materazzi G, Berti P. Minimally invasive thyroidectomy in the treatment of well differentiated thyroid cancers: indications and limits. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18:114–118. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283378239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryu HR, Kang SW, Lee SH, et al. Feasibility and safety of a new robotic thyroidectomy through a gasless, transaxillary single-incision approach. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:e13–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Tielsch JM, Powe NR, Gordon TA, Udelsman R. The importance of surgeon experience for clinical and economic outcomes from thyroidectomy. Ann Surg. 1998;228:320–330. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stojadinovic A, Shaha AR, Orlikoff RF, et al. Prospective functional voice assessment in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. Ann Surg. 2002;236:823–832. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200212000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Triponez F, Poder L, Zarnegar R, et al. Hook needle-guided excision of recurrent differentiated thyroid cancer in previously operated neck compartments: a safe technique for small, nonpalpable recurrent disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4943–4947. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCoy KL, Yim JH, Tublin ME, Burmeister LA, Ogilvie JB, Carty SE. Same-day ultrasound guidance in reoperation for locally recurrent papillary thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2007;142:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shammas A, Degirmenci B, Mountz JM, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with suspected recurrent or metastatic well-differentiated thyroid cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]